Since the last issue of the Annals, the following letters have been published on our website <http://www.rcseng.ac.uk/publications/eletters/>:

I read this technical tip with interest and a degree of nostalgia. It is very similar to the technique my colleagues and I described in 1996 for distal interlocking in femoral nailing.1

Over the years I have largely abandoned this technique, particularly as in most intramedullary nailings the jigged proximal locking is completed prior to the distal locking, thus blocking the canal at an early stage; the exception of course being transverse shaft fractures, which may benefit from distal locking then back-slapping to ensure impaction and to minimise the ‘osteocyte jumping distance’ of the fracture gap.

If the ‘sounding’ technique is to be employed, it is worth reiterating the precautions: ensure that the guidewire is not visible across the chosen distal interlocking hole when targeting with the image intensifier and do not operate the drill when the guidewire is at the level of the interlocking hole. Breaking or damaging the drill bit is thus avoided. Many of us know colleagues who have successfully inserted distal locking bolts with the guidewire still in place, much to everyone's amusement except their own!

Footnotes

COMMENT ON doi: 10.1308/003588408X285991 Newton Ede MP, Garrick M, Shah NA. ‘Sounding’ the bolt: confirming the position of the locking bolts in an intramedullary nail. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2008; 90: 343–347.

Reference

- 1.Palmer SH, Britten S, Ellis S. A useful tip for distal interlocking in femoral intramedullary nailing. Injury. 1996;27:528. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(96)00075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

We agree that this technique is used rarely in femoral nailing due to the jigged proximal locking usually preceding the distal. We have employed the technique mostly in locked tibial nailings.

The precautions you describe are wise. You allude to the practice of using the ‘sounding technique’ to confirm the presence of the drill through the nail (before bolt insertion).We agree that sounding the drill bit prior to the bolt is hazardous. It is all too easy to do when the sounding is being performed by the assistant, while the surgeon holds the drill. Miscommunication can result in simultaneous sounding and drilling, resulting in a broken drill bit, irretrievable on the far side of the nail within the soft tissues. The authors have already accrued one such X-ray as a result.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge a previous description of a similar technique; its citation was prevented by the single reference limit. We are pleased that its description and pitfalls should be considered in the contemporary literature by today's trainees, for whom distal locking is often the frustrating end to a simple operation.

I read with great interest your paper on injury to the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve during minimally invasive hip surgery. I acknowledge the need to avoid painful neuroma formation following injury to the nerve and consequently to enhance rehabilitation and patient satisfaction.

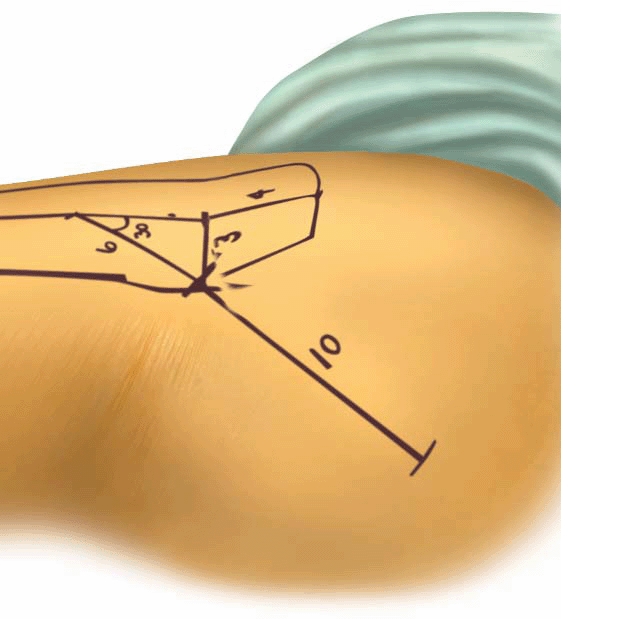

It does appear beneficial from your study to adopt the anterolateral approach for this purpose. However, I would have been intrigued to discover the number of branches divided using the popular minimally invasive posterior approach, devised by TV Swanson, and Smith and Nephew.2,3 This mini-posterior-oblique (Figure. 1) incision could potentially preserve more cutaneous branches than other minimally invasive approaches.

Figure 1.

Posterior oblique incision

Footnotes

References

- 2.Swanson TV. Early results of 1000 consecutive, posterior, single-incision minimally invasive surgery total hip arthroplasties. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20(7 Suppl 3):26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swanson TV. Posterior single-incision approach to minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2007;31(Suppl 1):S1–5. doi: 10.1007/s00264-007-0436-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

We appreciate your interest in our article. We agree with your hypothesis that the posterior minimally invasive surgery (MIS) approach you describe may result in a low risk of damage to the cutaneous nerves. Positioning the incision to run parallel with cutaneous nerves reduces the risk of damage and may prevent avoidable post-operative symptoms, including neuroma formation, which may hinder the patient's rehabilitation and satisfaction. In the area you describe, overlying gluteus maximus, the predominant cutaneous supply arises from the lateral cutaneous branch of iliohypogastric nerve and, to a lesser extent, the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve of the thigh. Nerve branches almost certainly travel in a similar fashion to those of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve of the thigh, from superomedial to inferolateral. However, in our cadaver study we did not examine this area and therefore cannot definitively comment on the exact course of these branches in our subjects.

As stated in our article, there are a number of reasons for positioning an incision in a particular fashion, which may ultimately have greater importance than cutaneous nerve preservation. To that end a surgeon must use an approach with which he or she is most familiar, which provides the best exposure and results in the greatest functional outcome and implant longevity.

I read Malahias's method to facilitate exploration of nail gun njuries to the hand with significant interest. In the photograph (Figure 2) I find it hard to see how any hand surgeon laying open the tract would make a larger exploratory incision than the one already made and thus the technique described seems not to fulfil its key objective. Furthermore, laying open the tract once the skin flap is raised does not produce any larger a skin wound but allows the surgeon to perform curettage of the tract and gives him or her confidence that he or she has explored the area involved adequately and has repaired injury not clinically perceptible.4,5

I fail to see how this rather fiddly technique offers the surgeon or the patient any advantage whatsoever and it may actually serve to increase the surgical time in a procedure that may be largely inadequate. Perhaps this is an elegant technique to write up but its lack of pragmatism and any obvious benefits, enshrouded in its oversimplicity, suggests that this is its only advantage and that this is not a technique that should be used on our patients.

Footnotes

COMMENT ON doi 10.1308 003588408X261618 Malahias M. Nail gun injuries: a simple method to facilitate exploration. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2008; 90: 523–526.

References

- 4.Van Demark RE, Jr, Van Demark RE., Sr Nailgun injuries of the hand. J Orthop Trauma. 1993;7:506–9. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199312000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hussey K, Knox D, et al. Nail gun injuries to the hand. J Trauma. 2008;64:170–3. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3180d09996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

We read the paper by Mullerat et al with interest as we recently had to deal with an unusual complication due to spilled gallstones. A 73-year-old woman presented with a right gluteal lesion discharging pus. On surgical exploration the tract was found to extend through the anterior abdominal wall into the abdomen at the level of the iliac crest. A CT scan revealed a perihepatic collection. Ultrasound showed high-density bodies with acoustic shadowing within the collection, consistent with gallstones. Subsequently it came to light that seven years earlier she had had a cholecystectomy. This was initially attempted laparoscopically but converted to open surgery due to difficulties in which rupture of the gallbladder and spillage of stones occurred. The patient was unaware of this.

The collection was drained under ultrasound guidance and antibiotic therapy was given. The gluteal wound healed uneventfully and a subsequent CT scan showed complete resolution of the collection. While we support Mullerat et al's call to inform the patient and GP when gall stone spillage occurs, it is worth pointing out that some complications can occur years later and may present well away from the immediate vicinity of the gall bladder.