Abstract

Purpose of review

Orofacial clefts are common birth defects with a known genetic component to their etiology. Most orofacial clefts are nonsyndromic, isolated defects, which can be separated into two different phenotypes: (1) cleft lip with or without cleft palate and (2) cleft palate only. Both are genetically complex traits, which has limited the ability to identify disease loci or genes. The purpose of this review is to summarize recent progress of human genetic studies in identifying causal genes for isolated or nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate.

Recent findings

The results of multiple genome scans and a subsequent meta-analysis have significantly advanced our knowledge by revealing novel loci. Furthermore, candidate gene approaches have identified important roles for IRF6 and MSX1. To date, causal mutations with a known functional effect have not yet been described.

Summary

With the implementation of genome-wide association studies and inexpensive sequencing, future studies will identify disease genes and characterize both gene–environment and gene–gene interactions to provide knowledge for risk counseling and the development of preventive therapies.

Keywords: cleft lip, cleft palate, epistasis, environment, genome scan, heterogeneity

Introduction

It is generally accepted that cleft lip with or without cleft palate (CL/P) and cleft palate only (CPO) are genetically distinct phenotypes in terms of their inheritance patterns. CPO is less common, with a prevalence of approximately 1/1500–2000 births in Caucasians, whereas CL/P is more common, 1–2/1000 births. The prevalence of CPO does not vary in different racial backgrounds, whereas the prevalence of CL/P varies considerably, with Asian and American Indians having the highest rate and Africans the lowest [1]. Orofacial clefts can be further classified as non-syndromic (isolated) or syndromic based on the presence of other congenital anomalies. Approximately 20–50% of all orofacial clefts are associated with one of more than 400 described syndromes [2]. These syndromes often have simple Mendelian inheritance patterns and are thus amenable to gene identification.

Genetics of human orofacial clefting

Studies of orofacial clefting have shown that CL/P has complex inheritance patterns as evidenced by a positive family history for clefting in 33% of the patients, no clearly recognizable mode of inheritance, and reduced penetrance [3]. The relative risk for siblings (λs), defined as the prevalence in siblings of an affected individual divided by the population prevalence, is 40; there is a 2–5% increased risk for offspring of affected individuals and a greater concordance in monozygotic than dizygotic twins, all providing evidence that genetic factors play an etiologic role. Yet, segregation analyses have not conclusively defined the mode of inheritance [3]. Studies have estimated that 3–14 genes interacting multiplicatively may be involved, indicating that CL/P is a heterogeneous disorder [4]. Relative risks for a given gene are estimated to be in the range of 2–12, which are sufficiently large enough for identification by positional mapping approaches [5,6]. Human studies have used both association and linkage analyses to evaluate the role of candidate genes in the etiology of CL/P. Association mapping is the identification of nonrandom correlations (associations) between alleles at two loci in a population. The assumption is that affected individuals have a shared ancestor on whose chromosomes the original mutation arose. This would result in shared alleles for markers near the mutation among affected individuals, whereas recombination, which has occurred throughout the entire history of the population, would result in random segregation of the regions outside of the disease locus. Linkage mapping looks for the cosegregation of alleles for genetic markers with a disease phenotype in a family. Association approaches have more study power; however, the use of a combination of both linkage and association can also be successful for complex traits [7].

Candidate genes

Initial efforts to identify genes for nonsyndromic CL/P relied on candidate gene approaches [8,9]. Loci at 1q32 (IRF6), 2p13 (TGFA), 4p16 (MSX1), 6p23-25, 14q24 (TGFB3), 17q21 (RARA), and 19q13 (BCL3, TGFB1) have the most supporting data (Table 1).

Table 1. Selected examples of candidate genes studied for a role in nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate.

| Candidate region | Candidate gene | Linkage | Association | Animal model | Chromosome anomaly | Cleft syndrome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1p36 | MTHFR, SKI, PAX7 | X | X | X | ||

| 1q32 | IRF6 | X | X | X | X | X |

| 2p13 | TGFA | X | X | |||

| 4p16 | MSX1 | X | X | X | X | |

| 6p23-25 | TFAP2A, OFCC1 | X | X | X | X | |

| 14q24 | TGFB3, BMP4, PAX9 | X | X | X | ||

| 17q12-21 | RARA, Clf1 | X | X | X | ||

| 19q13 | BCL3, CLPTM1, PVRL2, TGFB1 | X | X | X |

IRF6 variants are associated with increased risk for cleft lip with or without cleft palate

Mutations in IRF6 at 1q32 cause the Van der Woude syndrome, which includes lower lip pits in addition to CL/P or CPO [10]. Given the overlapping phenotype with isolated CL/P, IRF6 was screened for a causal role, revealing a highly significant association [11•]. Variation at the IRF6 locus is responsible for 12% of the genetic contribution to CL/P at the population level and triples the recurrence risk for a child with a cleft in some families. Similar results have been reported in additional populations [12–14]. However the specific causal variants have yet to be functionally identified. These data clearly indicate that IRF6 is significant risk factor for CL/P and constitutes one of the most exciting discoveries so far, because it provides tangible evidence that genetic variants involved in nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate can be successfully mapped. In addition, this finding underscores the importance of studying syndromic forms of clefting to provide insight about the more complex nonsyndromic forms [15•].

2p13 (TGFA)

Since the first study showing association of TGFA with CL/P [16], many additional studies have replicated this finding [9]. However, other studies have not been able to replicate this finding by either linkage or association [9,17,18]. Two meta-analyses, one looking at association studies [19] and a more recent study combining 13 genome scan studies [20•], reveal positive results, corroborating the hypothesis that TGFA is a modifier rather than necessary or sufficient to cause clefting.

4p16 – MSX1

The occurrence of cleft palate in MSX1 knockout mice aided the identification of a MSX1 mutation cosegregating with tooth agenesis, CL/P, and/or CPO [21]. Recently, mutations in MSX1 have been identified in 2% of patients with nonsyndromic orofacial clefting [22,23•]. These data support previous associations of MSX1 with orofacial clefting [9,24–28].

6p23-p25 Region

The first significant linkage finding for nonsyndromic CL/P was reported in a Danish study [29]. Since this report, positive evidence of linkage and association, as well as chromosomal rearrangements, have been reported. Furthermore, a meta-analysis of genome scans found significant linkage indicating half of the families have a disease mutation in this region [20•]. One potential candidate gene is TFAP2A since mice chimeric for Ap-2α null alleles have CL/P, which is a rare occurrence in genetically modified mice [30]. Breakpoints have been mapped 375–930 kb distal of TFAP2A, ruling out a direct effect [31]. Rather a novel gene, OFCC1, of unknown function but expressed in the palate is transected by one rearrangement.

14q24 – TGFB3

Tgfb3 knockout mice present with cleft palate [32,33], and subsequent human studies have yielded both positive and negative results [9]. A recent genome scan meta-analysis for CL/P identified significant linkage to the TGFB3 region [20•]. Nevertheless, only 15% of the families were linked to this region, which may in part explain previous inconsistencies. Nearby genes include BMP4 and PAX9, both associated with orofacial clefting when inactivated in mice [34,35].

17q12-q21 (RARA, Clf1)

Retinoic acid has a well established role during development, and its activity is mediated by members of the retinoic acid receptor family. Transgenic and knockout mice studies have shown that these genes are important for facial development [36,37]. Various human studies have reported both positive and negative results near the RARA gene. One study showed association to a marker 4 cM from RARA [38], an unexpected result over such a large genetic distance. Interestingly, this marker is near the syntenic region for the mouse Clf1 locus [39•]. The recent meta-analysis of genome scans revealed significant results for the 17q12-21 region that also includes the syntenic Clf1 region [20•]. Potential candidate genes in this region include WNT3 and WNT9B. In humans, a nonsense mutation in WNT3 causes tetra-amelia, a rare autosomal recessive syndrome that includes cleft lip as part of the phenotype [40].

19q13.1 (BCL3, CLPTM1, PVRL2, TGFB1)

Evidence for a cleft susceptibility locus in the 19q13.1 region has been found from linkage and association studies [9,41,42], as well as a translocation cosegregating with CL/P [43]. A variety of genes have been studied, including BCL3, PVRL2, CLPTM1, and TGFB1. BCL3 is a proto-oncogene that is involved in cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. The CLPTM1 gene encodes a transmembrane protein that is expressed in embryonic tissues. PVRL2 is a transmembrane glycoprotein that belongs to the poliovirus receptor family. Mutations in a related protein, PVRL1, are known to cause the autosomal recessive Margarita Island clefting syndrome [44], and heterozygotes for the PVRL1 W185X mutation are thought to have increased risk for nonsyndromic CL/P [45]. TGFB1 mutations in humans have been found to cause the Camurati–Engelmann-syndrome [46], which is a progressive diaphyseal dysplasia that does not include an orofacial clefting phenotype, even though TGFB1 is expressed in the palate [47].

Genome scans identify novel loci

Recent developments in high-throughput genotyping technologies and powerful statistical approaches have accelerated the discovery of loci conferring susceptibility for complex diseases through the use of genome scans [48]. The first CL/P scan was performed on 92 British sibpairs and identified a total of nine regions with suggestive results [49]. This has been followed by five additional scans of varying size (Table 2) [20,24,49–54]. In general, the results have been modest with the exception of a log odds ratio (LOD) score of 3.0 at 17p13.1 in a scan of two large Syrian families [50]. The most consistent loci are 2p13 (TGFA), 2q35-q37, 3p21-p24, 4q32-q33, 6p23-p25, 9q22-q33, 14q12-q31, and 18q11-q12, with the remaining 23 loci being unique to the population studied. These results reflect genetic heterogeneity both within and between populations, limited study power, and a likely high false-positive rate for loci with low levels of significance.

Table 2. Cleft lip with or without cleft palate genome-wide scans.

| Prescott et al., 2000 [49] | Marazita et al., 2002 [91] | Wyszynski et al., 2003 [50] | Zeiger et al., 2003 [92] | Marazita et al., 2004 [24] | Field et al., 2004 [93] | Moreno et al., 2005 [94] | Marazita et al., 2004 [20•] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosome | 92 Sibpairs from the UK | 36 Multiplex families from China | 2 large families from Syria | 26 Families from Mexico, Argentina, and the United States | 18 families from Turkey | 38 from India | 48 Colombian families and 9 families from Ohio | Meta-analysis of 574 families total from 13 studies |

| 1 | 1p36 | 1p31 | 1q44 | 1p22-p33 | 1p12-13 1q32 | |||

| 2 | 2p13 | 2q35-q36 | 2q37 | 2p12-24 | 2q32-q35 | |||

| 3 | 3q24-q26 | 3p21.2 | 3p24 | 3q26q-28 3p14-p23 | 3p25 | |||

| 4 | 4q32-q33 | 4q32.1 | 4p12 | |||||

| 5 | 5q11 | |||||||

| 6 | 6p24-23 6q25 | 6q14 | 6p23 6q23-25 | |||||

| 7 | 7q21 | 7q34 | 7p15 | 7p12 | ||||

| 8 | 8q23-24 | 8q11.2-q12 | 8p21 8q23 | |||||

| 9 | 9q21-22 | 9q22-q33 | 9q21 | |||||

| 10 | 10q23-q26 | |||||||

| 11 | 11p12-q14 | |||||||

| 12 | 12p11-q24 | 12q24 | 12p11 | |||||

| 13 | 13q12 | |||||||

| 14 | 14q12 | 14q11-q22 14q24-q31 | 14q21-24 | |||||

| 15 | 15q26 | 15q11-q13.3 | 15q15 | |||||

| 16 | 16q22-24 | |||||||

| 17 | 17p13.1 | 17q11.2 | 17q11-q21 | 17q21 | ||||

| 18 | 18q11.2-q12 | 18q12 | 18q21 | |||||

| 19 | 19q13.3 | |||||||

| 20 | 20p12 | 20q13 | 20q13 | |||||

| 21 | ||||||||

| 22 | ||||||||

| X | Xcen-q21 | |||||||

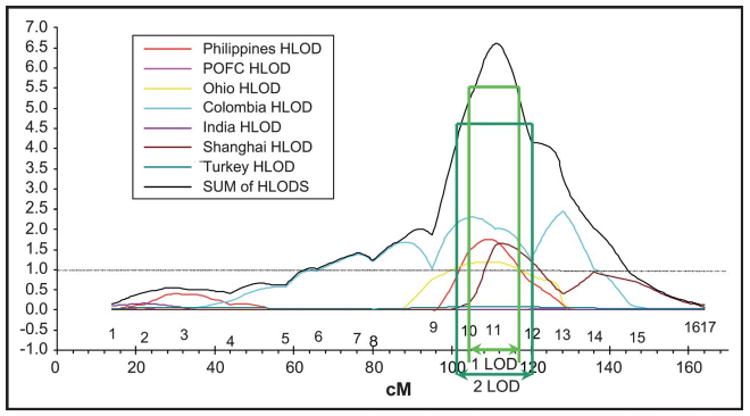

To address these limitations and increase the information yield from these expensive studies, a meta-analysis was performed in which data from six published and seven ongoing genome scans were combined (Table 2) [20•]. Significant results were obtained for regions 1q32, 2q32-q35, 3p25, 6q23-q25, 8p21, 8q23, 12p11, 14q21-q24, 17q21, 18q21, and 20q13. In addition to the meta-analysis, multipoint parametric heterogeneity LOD score (HLODs) results were summed among seven of the 13 populations that were genotyped with the same markers. Significant results (HLODS>3.5) were observed for chromosomal regions 1p12-p13, 6p23, 6q23-q25, 9q22-q33, 14q21-q24, and 15q15. Most remarkable was the highly significant result for 9q22-q33 (HLOD = 6.6), which is the most significant result ever reported for CL/P and also represents a new locus for clefting (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Summed dominant heterogeneity log odds ratio scores from seven different populations.

The green arrows indicate the 1 and 2 log odds ratio intervals of linkage. Modified from [20].

Genes in environmental pathways

‘One of the most important benefits of identifying the genetic factors in disease susceptibility may not be the potential for gene therapy, as exciting a prospect as that is, but rather the opportunity for treatment and prevention of clinical disease by manipulating the environment of individuals identified to be genetically at risk’ [55 pp.411].

The low monozygotic concordance rate (25–50%) for CL/P suggests that environmental factors also are involved. It is well recognized that alcohol [56] and smoking [57] increase the risk for CL/P, and there is evidence that folate supplementation decreases the risk [58]. Clearly it is likely that the environment interacts with both the maternal and fetal gene products, supporting the hypothesis that genetic variation in involved pathways modulates CL/P risk.

Initial studies took a convenience approach and looked for the interaction of candidate genes and either smoking or alcohol. Studies of gene–environment interaction in orofacial clefting have evaluated candidate genes such as TGFA, TGFB3, MSX1, BCL3, and RARA and environmental behaviors including smoking, alcohol use, and vitamin intake [59]. Results from these studies have shown modest association and, at times, inconsistent results. One of the more consistent findings is the interaction of smoking and TGFA variants, specifically for CP as determined by a recent meta-analysis [60].

A number of investigators have concentrated on the folate pathway, buoyed by the significant evidence for neural tube prevention and a similar trend for CL/P prevention by folate supplementation. Most studies have focused on two MTHFR polymorphisms (C677T or A298C), both of which cause reduced enzymatic activity. Results of several association studies have been contradictory, which may be due to different analytic strategies, specifically whether the analysis focused on the proband or maternal genotype [58]. Alternately, assuming that MTHFR is not sufficient but necessary to cause CL/P, analytical strategies that consider the simultaneous effects of different loci or that take into account environmental covariates may be more powerful for detecting the relation between MTHFR and CL/P [61]. For example, functional RFC1 and MTHFR variants in probands revealed no association with CL/P in a South American population [62]. However, a log-linear–based method revealed a gene–environment interaction between CP infants carrying either CT or TT genotypes at MTHFR and maternal folic acid consumption [63] and another study found similar findings for CL/P [64]. Also, an increased risk has been observed for maternal MTHFR variants [65,66]. This has been extended to another gene in the homocysteine pathway, CBS, in which maternal transmission resulted in a 19-fold increased risk [67]. Inactivation of the folate-binding protein, Folbp1, results in CL/P in mice [68]. However, minimal evidence of linkage (NPL P = 0.056) and no mutations were observed in an Italian study [69].

More recently, investigators have taken a more biologic approach to evaluate genes involved in absorption, detoxification, and response to environmental teratogens. Among these molecules are the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) and AHR nuclear translocator (ARNT), which are affected by exposure to dioxins that are commonly found in food [70], cigarette smoke, incinerators, automobile exhaust, and industrial chlorine bleaching [71]. ARNT is a basic helix-loop-helix protein that is a cofactor for AHR in the mediation of dioxin effects to modulate downstream genes such as TGFA, TGFB, EGF, and EGFR [72], some of the same genes shown previously to be associated with CL/P. Interestingly, ARNT is located on mouse chromosome 7 within a 300 kb deletion associated with cleft palate [73]. Association studies in the Japanese population have shown significant over transmission of alleles within the ARNT gene; however, joint gene–environmental effects were not explored in this study [74].

Studies of the biotransformation enzymes P450 (CYP1A1) and glutathione S-transferase theta 1-1 (GSTT1) have revealed a higher, although not significant, risk for smoking mothers carrying the GSTT1-null genotype compared with nonsmokers carrying the wild-type genotype, whereas no interactions were seen for P450 (CYP1A1) genotypes and cigarette exposure [64]. Finally, infants homozygous for NAT1 polymorphisms, a gene involved in detoxification of cigarette smoke, had a twofold or fourfold increased risk for CL/P if their mothers did not use multivitamins or smoked, respectively [75,76].

Interestingly, a decreased risk for CL/P was detected for the functional Ser326Cys variant in the human 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase (hOGG) base excision repair gene, whereas the same variant resulted in increased risk for neural tube defects [77]. It will be interesting to determine whether any environmental factors modulate this risk.

Genetic interactions

For complex traits it is likely that gene–gene interactions contribute to disease risk. For CL/P, evidence for this exists in the A/WySn mouse strain in which the Clf1 and Clf2 loci epistatically interact [78]. The utility of gene–gene analyses to either narrow a critical region [79] or to identify additional loci [80] has been demonstrated for other diseases.

Interaction between two loci has been observed for CL/P in which Italian families initially linked to 6p23 showed significant linkage to 2p13 [81]. Another interesting genetic interaction is between MTHFR and CBS, suggesting that variations in multiple genes in the folate pathway may need to be evaluated to identify an increased risk [67].

Finally, an interaction between maternal MTHFR and infant BCL3 polymorphisms has been described [82]. These interactions are important in roads toward a further understanding of the underlying genetic complexity.

Syndromic orofacial clefts provide important clues

Considerable success has been achieved in identifying etiologic genes for syndromic forms of orofacial clefting, with approximately 15–20% cloned to date [83•]. In addition to the IRF6 and PVRL1 examples, efforts are underway to determine whether variants in other cleft syndrome genes are associated with nonsyndromic clefting. Mutations and deletions in FGFR1 account for 10% of patients with Kallmann syndrome, which is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by orofacial clefting, dental anomalies, hypogonadism, and anosmia [84]. Suggestive association and linkage to CL/P has been found for markers within the FGFR1 gene, again underscoring the importance of studying syndromic forms of clefting [85].

The future looks bright

The future is now for genome association scans involving 200–500K markers [86,87•]. Affordable technology exists to evaluate the thousands of samples necessary for adequate power. Also on the horizon for CL/P are clever methods using both simple and sophisticated phenotyping techniques to identify gene carriers [88,89]. This information will significantly improve the power of each family for linkage studies, aid in determining risk estimates, and also be used as covariates to identify distinct subgroups. The identification of gene–environment interactions will be greatly aided by the ongoing National Study of Birth Defects Prevention [90]. Finally, new analytic strategies are being developed and tested to identify genetic epistasis and address the known heterogeneity of genetically complex traits [91].

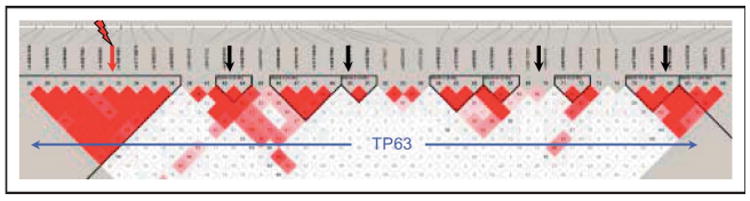

A recent development that deserves notice is the International HapMap project to identify patterns of association between markers within the human genome [92]. It is well recognized that association can occur in segments – termed haplotype blocks [93,94], and significant efforts are ongoing to describe genomic patterns of association in four ethnic groups of African, Asian, and European ancestry. Knowledge of haplotype block structure will provide an estimate of the likelihood for detecting association over various genetic distances and vastly increase the utility of future association-based genome scans. Also, knowledge of haplotype blocks may also explain contradictory results from candidate gene association studies. For example the TGFBR1 gene is contained in one large linkage disequilibrium block, indicating that if a mutation arose within the block, almost any marker in the block would identify it in an association study (Fig. 2). Alternately, the TP63 gene spans multiple blocks. If a common disease mutation is in the first block, markers in the other regions would not reveal an association with this gene (Fig. 3).

Figure 2. Association plot of the TGFBR1 gene.

Upper left, HapMap view of TGFBR1 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Upper level shows SNP markers genotyped by the HapMap Project. Lowest level displays gene structure for TGFBR1. Right, Association plot of the TGFBR1 gene. Association of marker pairs is indicated by a red-white gradient, with red being highly associated and white being relatively unassociated. The location of the TGFBR1 gene is defined by the blue arrows. A hypothetical mutation is indicated by the red arrow and markers by black arrows Lower left, Haplotypes of TGFBR1 SNP markers showing association between the markers.

Figure 3. Association plot of the TP63 gene.

The location of the TP63 gene is defined by the blue arrows. A hypothetical mutation is indicated by the red arrow and markers by black arrows.

Conclusion

In general, the gene identification process for CL/P is still in the early stages because of the genetic complexity of clefting. Results from the studies presented here support the presence of heterogeneity among populations and also the presence of multiple genes involved in the etiology of this trait. The challenge is now to fine map these regions and identify genes in which variants are more likely to increase the risk for CL/P. Therefore, it is anticipated that there are additional genes involved in CL/P that have yet to be identified, and the functional effects of identified mutations have yet to be discerned. Furthermore, the genetic interaction with environmental factors will become more evident through studies evaluating maternal and fetal genotypes along with gestational environmental exposures. With the recent publication of genome-wide linkage scans and similar ongoing studies, the field is rapidly making advances toward positional cloning of etiologic genes.

Acknowledgments

Our work has been greatly aided by discussions with Mauricio Arcos-Burgos, Sandy Daack-Hirsch, Mike Dixon, David FitzPatrick, Brion Maher, Mary Marazita, Brian Schutte, Alex Vieira, and George Wehby. Unfortunately, we were unable to cite all the significant contributions of our colleagues because of space limitations.

LMM is supported by a Fogarty International Maternal and Child Health Research and Training Fellowship (1D43 TW-05503), and ACL is supported by NIH Grants RO1DE14677, KO2DE015291, and P50DE016215 with additional funding from the University of Iowa Craniofacial Anomalies Research Center, brilliantly directed by Jeff Murray, and the College of Dentistry

Abbreviations

- AHR

aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- AHRNT

aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator

- CL/P

cleft lip with or without cleft palate

- CPO

cleft palate only

- HLOD

heterogeneity log odds ratio

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

Additional references related to this topic can also be found in the Current World Literature section in this issue (p. 798).

- 1.Forrester MB, Merz RD. Descriptive epidemiology of oral clefts in a multiethnic population, Hawaii, 1986–2000. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2004;41:622–628. doi: 10.1597/03-089.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorlin RJ, Cohen MM, Hennekam RCM. Syndromes of the head and neck. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wyszynski DF. Cleft lip and palate: from origin to treatment. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schliekelman P, Slatkin M. Multiplex relative risk and estimation of the number of loci underlying an inherited disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:1369–1385. doi: 10.1086/344779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell LE, Christensen K. Analysis of the recurrence patterns for nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate in the families of 3,073 Danish probands. Am J Med Genet. 1996;61:371–376. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960202)61:4<371::AID-AJMG12>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farrall M, Buetow KH, Murray JC. Resolving an apparent paradox concerning the role of TGFA in CL/P. Am J Hum Genet. 1993;52:434–436. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horikawa Y, Oda N, Cox NJ, et al. Genetic variation in the gene encoding calpain-10 is associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Genet. 2000;26:163–175. doi: 10.1038/79876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carinci F, Pezzetti F, Scapoli L, et al. Recent developments in orofacial cleft genetics. J Craniofac Surg. 2003;14:130–143. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200303000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marazita ML, Mooney MP. Current concepts in the embryology and genetics of cleft lip and cleft palate. Clin Plast Surg. 2004;31:125–140. doi: 10.1016/S0094-1298(03)00138-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kondo S, Schutte BC, Richardson RJ, et al. Mutations in IRF6 cause Van der Woude and popliteal pterygium syndromes. Nat Genet. 2002;32:285–289. doi: 10.1038/ng985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11•.Zucchero TM, Cooper ME, Maher BS, et al. Interferon regulatory factor 6 (IRF6) gene variants and the risk of isolated cleft lip or palate. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:769–780. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; It is important to note that there was minimal evidence of linkage to IRF6 for each population, and a genome scan meta-analysis revealed only modest evidence of linkage to this region [21]. This underscores the underlying assumptions and complementary strengths and weaknesses of linkage, and linkage disequilibrium approaches and highlights the need for very large study populations.

- 12.Houdayer C, Bonaiti-Pellie C, Erguy C, et al. Possible relationship between the van der Woude syndrome (VWS) locus and nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate (NSCL/P) Am J Med Genet. 2001;104:86–92. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20011115)104:1<86::aid-ajmg10053>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scapoli L, Palmieri A, Martinelli M, et al. Strong evidence of linkage disequilibrium between polymorphisms at the IRF6 locus and nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate, in an Italian population. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:180–183. doi: 10.1086/427344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srichomthong C, Siriwan P, Shotelersuk V. Significant association between IRF6 820G->A and non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate in the Thai population. J Med Genet. 2005;42:e46. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.032235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15•.Stanier P, Moore GE. Genetics of cleft lip and palate: syndromic genes contribute to the incidence of nonsyndromic clefts. Hum Mol Genet. 2004 April 1;13(Spec No 1):73–81. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh052. ddh052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; An excellent review highlighting the importance of studying rare disorders.

- 16.Ardinger HH, Buetow KH, Bell GI, et al. Association of genetic variation of the transforming growth factor-alpha gene with cleft lip and palate. Am J Hum Genet. 1989;45:348–353. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jugessur A, Lie RT, Wilcox AJ, et al. Variants of developmental genes (TGFA, TGFB3, and MSX1) and their associations with orofacial clefts: a case-parent triad analysis. Genet Epidemiol. 2003;24:230–239. doi: 10.1002/gepi.10223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Passos-Bueno MR, Gaspar DA, Kamiya T, et al. Transforming growth factor-alpha and nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without palate in Brazilian patients: results of a large case-control study. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2004;41:387–391. doi: 10.1597/03-054.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell LE. Transforming growth factor alpha locus and nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate: a reappraisal. Genet Epidemiol. 1997;14:231–240. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2272(1997)14:3<231::AID-GEPI2>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20•.Marazita ML, Murray JC, Lidral AC, et al. Meta-analysis of 13 genome scans reveals multiple cleft lip/palate genes with novel loci on 9q21 and 2q32-35. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:161–173. doi: 10.1086/422475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is the first meta-analysis at a genome level for CL/P. Furthermore, the sheer size provides overwhelming evidence for new loci at 2q32-35 and 9q21.

- 21.van den Boogaard MJ, Dorland M, Beemer FA, et al. MSX1 mutation is associated with orofacial clefting and tooth agenesis in humans. Nat Genet. 2000;24:342–343. doi: 10.1038/74155. published erratum appears in. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Nat Genet. 2000 May;25(1):125. doi: 10.1038/75532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jezewski PA, Vieira AR, Nishimura C, et al. Complete sequencing shows a role for MSX1 in non-syndromic cleft lip and palate. J Med Genet. 2003;40:399–407. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.6.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23•.Suzuki Y, Jezewski PA, Machida J, et al. In a Vietnamese population, MSX1 variants contribute to cleft lip and palate. Genet Med. 2004;6:117–125. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000127275.52925.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study also found that mutations in the MSX1 gene are responsible for 2% of the cases in this Vietnamese population.

- 24.Marazita ML, Field LL, Tuncbilek G, et al. Genome-scan for loci involved in cleft lip with or without cleft palate in consanguineous families from Turkey. Am J Med Genet. 2004;126A:111–122. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moreno LM, Arcos-Burgos M, Marazita ML, et al. Genetic analysis of candidate loci in non-syndromic cleft lip families from Antioquia-Colombia and Ohio. Am J Med Genet. 2004;125A:135–144. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schultz RE, Cooper ME, Daack-Hirsch S, et al. Targeted scan of fifteen regions for nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate in Filipino families. Am J Med Genet. 2004;125A:17–22. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vieira AR, Orioli IM, Castilla EE, et al. MSX1 and TGFB3 contribute to clefting in South America. J Dent Res. 2003;82:289–292. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suazo J, Santos JL, Carreno H, et al. Linkage disequilibrium between MSX1 and non-syndromic cleft lip/palate in the Chilean population. J Dent Res. 2004;83:782–785. doi: 10.1177/154405910408301009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eiberg H, Bixler D, Nielsen LS, et al. Suggestion of linkage of a major locus for nonsyndromic orofacial cleft with F13A and tentative assignment to chromosome 6. Clin Genet. 1987;32:129–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1987.tb03340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nottoli T, Hagopian-Donaldson S, Zhang J, et al. AP-2-null cells disrupt morphogenesis of the eye, face, and limbs in chimeric mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13714–13719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davies SJ, Wise C, Venkatesh B, et al. Mapping of three translocation breakpoints associated with orofacial clefting within 6p24 and identification of new transcripts within the region. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2004;105:47–53. doi: 10.1159/000078008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Proetzel G, Pawlowski SA, Wiles MV, et al. Transforming growth factor-B3 is required for secondary palate fusion. Nat Genet. 1995;11:409–414. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaartinen V, Voncken JW, Shuler C, et al. Abnormal lung development and cleft palate in mice lacking TGF-B3 indicates defects of epithelial-mesenchymal interaction. Nat Genet. 1995;11:415–421. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu W, Sun X, Braut A, et al. Distinct functions for Bmp signaling in lip and palate fusion in mice. Development. 2005 Mar;132(6):1453–61. doi: 10.1242/dev.01676. dev.01676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peters H, Neubuser A, Kratochwil K, et al. Pax9-deficient mice lack pharyngeal pouch derivatives and teeth and exhibit craniofacial and limb abnormalities. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2735–2747. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.17.2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lohnes D, Mark M, Mendelsohn C, et al. Function of the retinoic acid receptors (RARs) during development: (I) Craniofacial and skeletal abnormalities in RAR double mutants. Development. 1994;120:2723–2748. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.10.2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Damm K, Heyman RA, Umesono K, et al. Functional inhibition of retinoic acid response by dominant negative retinoic acid receptor mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2989–2993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shaw D, Ray A, Marazita M, et al. Further evidence of a relationship between the retinoic acid receptor alpha locus and nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Am J Hum Genet. 1993;53:1156–1157. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39•.Juriloff DM, Harris MJ, Dewell SL, et al. Investigations of the genomic region that contains the clf1 mutation, a causal gene in multifactorial cleft lip and palate in mice. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2005;73:103–113. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Report of the presence of a transposable element inserted nearby Wnt9b gene, which appears to be the clf1 mutation.

- 40.Niemann S, Zhao C, Pascu F, et al. Homozygous WNT3 mutation causes tetra-amelia in a large consanguineous family. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:558–563. doi: 10.1086/382196. Epub 2004 Feb 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blanco R, Suazo J, Santos JL, et al. Association between 10 microsatellite markers and nonsyndromic cleft lip palate in the Chilean population. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2004;41:163–167. doi: 10.1597/02-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fujita H, Nagata M, Ono K, et al. Linkage analysis between BCL3 and nearby genes on 19q13.2 and non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate in multigenerational Japanese families. Oral Dis. 2004;10:353–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2004.00995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoshiura KI, Machida J, Daack-Hirsch S, et al. Characterization of a novel gene disrupted by a balanced chromosomal translocation t(2;19)(q11.2;q13.3) in a family with cleft lip and palate. Genomics. 1998;54:231–240. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suzuki K, Hu D, Bustos T, et al. Mutations of PVRL1, encoding a cell–cell adhesion molecule/herpesvirus receptor, in cleft lip/palate-ectodermal dysplasia. Nat Genet. 2000;25:427–430. doi: 10.1038/78119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sozen MA, Suzuki K, Tolarova MM, et al. Mutation of PVRL1 is associated with sporadic, non-syndromic cleft lip/palate in northern Venezuela. Nat Genet. 2001;29:141–142. doi: 10.1038/ng740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kinoshita A, Saito T, Tomita H, et al. Domain-specific mutations in TGFB1 result in Camurati-Engelmann disease. Nat Genet. 2000;26:19–20. doi: 10.1038/79128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fitzpatrick DR, Denhez F, Kondaiah P, et al. Differential expression of TGF beta isoforms in murine palatogenesis. Development. 1990;109:585–595. doi: 10.1242/dev.109.3.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Altmuller J, Palmer LJ, Fischer G, et al. Genomewide scans of complex human diseases: true linkage is hard to find. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:936–950. doi: 10.1086/324069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Prescott NJ, Lees MM, Winter RM, et al. Identification of susceptibility loci for nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate in a two stage genome scan of affected sib-pairs. Hum Genet. 2000;106:345–350. doi: 10.1007/s004390051048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wyszynski DF, Albacha-Hejazi H, Aldirani M, et al. A genome-wide scan for loci predisposing to non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate in two large Syrian families. Am J Med Genet. 2003;123A:140–147. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gelehrter TD, Collins FS, Ginsburg D. Principles of medical genetics. Williams & Wilkins; 1998. p. 410. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jones KL, Smith DW, Ullelaand CN, et al. Pattern of malformation in offspring of chronic alcoholic mothers. Lancet. 1973;9:1267–1271. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)91291-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wyszynski DF, Duffy DL, Beaty TH. Maternal cigarette smoking and oral clefts: a meta-analysis. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1997;34:206–210. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_1997_034_0206_mcsaoc_2.3.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Prescott NJ, Malcolm S. Folate and the face: evaluating the evidence for the influence of folate genes on craniofacial development. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2002;39:327–331. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_2002_039_0327_fatfet_2.0.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murray J. Gene/environment causes of cleft lip and/or palate. Clin Genet. 2002;61:248–256. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2002.610402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zeiger JS, Beaty TH, Liang KY. Oral clefts, maternal smoking, and TGFA: a meta-analysis of gene-environment interaction. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2005;42:58–63. doi: 10.1597/02-128.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carmichael SL, Shaw GM, Yang W, et al. Maternal periconceptional alcohol consumption and risk for conotruncal heart defects. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2003;67:875–878. doi: 10.1002/bdra.10087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vieira AR, Murray JC, Trembath D, et al. Studies of reduced folate carrier 1 (RFC1) A80G and 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T polymorphisms with neural tube and orofacial cleft defects. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;135:220–223. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jugessur A, Wilcox AJ, Lie RT, et al. Exploring the effects of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene variants C677T and A1298C on the risk of orofacial clefts in 261 Norwegian case-parent triads. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:1083–1091. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van Rooij IALM, Vermeij-Keers C, Kluijtmans LAJ, et al. Does the interaction between maternal folate intake and the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphisms affect the risk of cleft lip with or without cleft palate? Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:583–591. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shotelersuk V, Ittiwut C, Siriwan P, et al. Maternal 677CT/1298AC genotype of the MTHFR gene as a risk factor for cleft lip. J Med Genet. 2003;40:e64. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.5.e64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pezzetti F, Martinelli M, Scapoli L, et al. Maternal MTHFR variant forms increase the risk in offspring of isolated nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Hum Mutat. 2004;24:104–105. doi: 10.1002/humu.9257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63•.Rubini M, Roberto B, Garattini G, et al. Cystathionine beta-synthase c.844ins68 gene variant and non-syndromic cleft lip and palate. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;136A:368–372. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ultimately, risk estimation models will focus on maternal genotype and environmental exposures, whereas actual risk will also include fetal genotypes.

- 64.Tang LS, Finnell RH. Neural and craniofacial abnormalities secondary to altered gene expression in the folic acid-binding protein 1 (Folbp1) deficient mouse embryo. Birth Defects Res Part A Clin Mol Teratol. 2003;67:209–218. doi: 10.1002/bdra.10045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Scapoli L, Marchesini J, Martinelli M, et al. Study of folate receptor genes in nonsyndromic familial and sporadic cleft lip with or without cleft palate cases. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;132:302–304. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liem AK, Furst P, Rappe C. Exposure of populations to dioxins and related compounds. Food Addit Contam. 2000;17:241–259. doi: 10.1080/026520300283324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Abbott BD. Developmental toxicity of dioxin: searching for the cellular and molecular basis of morphological responses. In: Kavlock RJ, Daston GP, editors. Drug toxicity in embryonic development: advances in understanding mechanisms of birth defects. New York: Springer; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Abbott BD, Probst MR, Perdew GH, et al. AH receptor, ARNT, glucocorticoid receptor, EGF receptor, EGF, TGF alpha, TGF beta 1, TGF beta 2, and TGF beta 3 expression in human embryonic palate, and effects of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) Teratology. 1998;58:30–43. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199808)58:2<30::AID-TERA4>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wines ME, Tiffany AM, Holdener BC. Physical localization of the mouse aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator-2 (Arnt2) gene within the c112K deletion. Genomics. 1998;51:223–232. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kayano S, Suzuki Y, Kanno K, et al. Significant association between nonsyndromic oral clefts and arylhydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT) Am J Med Genet. 2004;130A:40–44. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lammer EJ, Shaw GM, Iovannisci DM, et al. Periconceptional multivitamin intake during early pregnancy, genetic variation of acetyl-N-transferase 1 (NAT1), and risk for orofacial clefts. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2004;70:846–852. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lammer EJ, Shaw GM, Iovannisci DM, et al. Maternal smoking and the risk of orofacial clefts: Susceptibility with NAT1 and NAT2 polymorphisms. Epidemiology. 2004;15:150–156. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000112214.33432.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Olshan AF, Shaw GM, Millikan RC, et al. Polymorphisms in DNA repair genes as risk factors for spina bifida and orofacial clefts. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;135:268–273. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74•.Juriloff DM, Harris MJ, Dewell SL. A digenic cause of cleft lip in A-strain mice and definition of candidate genes for the two loci. Birth Defects Res Part A Clin Mol Teratol. 2004;70:509–518. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Mapping studies in mouse models for nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate have contributed to the selection of candidate genes, as well as furthering the understanding of some aspects of this trait's complexity such as the presence of a major gene, epistatic interactions, maternal effects, and epigenetic factors.

- 75.Cox NJ, Frigge M, Nicolae DL, et al. Loci on chromosomes 2 (NIDDM1) and 15 interact to increase susceptibility to diabetes in Mexican Americans. Nat Genet. 1999;21:213–215. doi: 10.1038/6002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pankratz N, Nichols WC, Uniacke SK, et al. Genome-wide linkage analysis and evidence of gene-by-gene interactions in a sample of 362 multiplex Parkinson disease families. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:2599–2608. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pezzetti F, Scapoli L, Martinelli M, et al. A locus in 2p13-p14 (OFC2), in addition to that mapped in 6p23, is involved in nonsyndromic familial orofacial cleft malformation. Genomics. 1998;50:299–305. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gaspar DA, Matioli SR, de Cassia Pavanello R, et al. Maternal MTHFR interacts with the offspring's BCL3 genotypes, but not with TGFA, in increasing risk to nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Eur J Hum Genet. 2004;12:521–526. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wilkie AO, Morriss-Kay GM. Genetics of craniofacial development and malformation. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:458–468. doi: 10.1038/35076601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sato N, Katsumata N, Kagami M, et al. Clinical assessment and mutation analysis of Kallmann syndrome 1 (KAL1) and fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1, or KAL2) in five families and 18 sporadic patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:1079–1088. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schultz RE. PhD thesis. University of Iowa; 2005. Idenification of genetic loci involved in nonsyndrome cleft lip with or without cleft palate. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lidral AC, Murray JC. Genetic approaches to identify disease genes for birth defects with cleft lip/palate as a model. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2004;70:893–901. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83•.Carlson CS, Eberle MA, Kruglyak L, et al. Mapping complex disease loci in whole-genome association studies. Nature. 2004;429:446–452. doi: 10.1038/nature02623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Comprehensive review of the current knowledge of association studies and critical aspects to consider when using these tools in mapping genes involved in complex traits.

- 84.Martin RA, Hunter V, Neufeld-Kaiser W, et al. Ultrasonographic detection of orbicularis oris defects in first degree relatives of isolated cleft lip patients. Am J Med Genet. 2000;90:155–161. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(20000117)90:2<155::aid-ajmg13>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nopoulos P, Berg S, Canady J, et al. Structural brain abnormalities in adult males with clefts of the lip and/or palate. Genet Med. 2002;4:1–9. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200201000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Khoury Muin J. Genetic susceptibility to birth defects in humans: from gene discovery to public health action. Teratology. 2000;61:17–20. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(200001/02)61:1/2<17::AID-TERA4>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87•.Maher BS, Brock GN. Approaches to detecting gene-gene interaction in genetic analysis workshop 14 pedigrees. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20119. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Provides an overview of the BMC Genetics issue focused on methods being developed or tested to identify gene–gene interactions in the 14th Genetic Analysis Workshop.

- 88.Gibbs RA, Belmont JW, Hardenbol P, et al. The International HapMap Project. Nature. 2003;426:789–796. doi: 10.1038/nature02168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wall JD, Pritchard JK. Haplotype blocks and linkage disequilibrium in the human genome. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:587–597. doi: 10.1038/nrg1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cardon LR, Abecasis GR. Using haplotype blocks to map human complex trait loci. Trends Genet. 2003;19:135–140. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Marazita ML, Field LL, Cooper ME, et al. Genome scan for loci involved in cleft lip with or without cleft palate, in Chinese multiplex families. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:349–364. doi: 10.1086/341944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zeiger JS, Hetmanski JB, Beaty TH, et al. Evidence for linkage of nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate to a region on chromosome 2. Eur J Hum Genet. 2003;11:835–839. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Field LL, Ray AK, Cooper ME, et al. Genome scan for loci involved in nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate in families from West Bengal, India. Am J Med Genet. 2004;130A:265–271. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Moreno LM, Arcos-Burgos M, Maher BS, et al. Genome scan for the complex trait, cleft lip, identifies major locus, genetic heterogeneity and genetic interactions. Unpublished data. [Google Scholar]