Abstract

Background

The current treatment intervention study determined the effect of coupled bilateral training (i.e., bilateral movements and EMG-triggered neuromuscular stimulation) and resistive load (mass) on upper extremity motor recovery in chronic stroke.

Methods

Thirty chronic stroke subjects were randomly assigned to one of three behavioral treatment groups and completed 6 hours of rehabilitation in 4 days: (1) coupled bilateral training with a load on the unimpaired hand, (2) coupled bilateral training with no load on the unimpaired hand, and (3) control (no stimulation assistance or load).

Results

Separate mixed design ANOVAs revealed improved motor capabilities by the coupled bilateral groups. From the pretest to the posttest, both the coupled bilateral no load and load groups moved a higher number of blocks and demonstrated more regularity in the sustained contraction task. Faster motor reaction times across test sessions for the coupled bilateral load group provided additional evidence for improved motor capabilities.

Conclusions

Together these behavioral findings lend support to the contribution of coupled bilateral training with a load on the unimpaired arm to improved motor capabilities on the impaired arm. This evidence supports a neural explanation in that simultaneously moving both limbs during stroke rehabilitation training appears to activate balanced interhemispheric interactions while an extra load on the unimpaired limb provides stability to the system.

Keywords: Chronic stroke, neurological rehabilitation, bilateral movement training, EMG-triggered neuromuscular stimulation, motor recovery

1. Introduction

Recent evidence supporting rehabilitation motor improvements for chronic stroke patients is both encouraging and challenging. Encouraging perspectives include the multiple treatment programs producing positive motor effects. Challenging perspectives include the diverse treatment programs that therapists must consider in selecting rehabilitation. Effective treatment programs gain efficacy through replication across studies as well as being able to successfully integrate and assimilate new approaches. The present study included these points in the design.

The replication aspect concerned the coupled bilateral protocols; simultaneous bilateral movement training of the wrist and fingers (extension) with supplemental active (EMG-triggered) neuromuscular stimulation on the impaired arm. A series of coupled bilateral training studies on stroke subjects in the chronic recovery phase revealed less hemiparesis on the impaired arm in comparison to unilateral training and control groups (Cauraugh, 2004; Cauraugh & Kim, 2002; Cauraugh & Kim, 2003b; Cauraugh & Summers, 2005). Moving two arms concurrently produces an interlimb coupling and the arms typically conform to temporal and spatial symmetry constraints (Cunningham et al., 2002; Swinnen & Wenderoth, 2004; Whitall et al., 2000).

Interlimb coupling and symmetry constraints provide a logical extension of this line of research to a new situation that determines the effect of an increased inertial load on the unimpaired hand of chronic stroke patients. Increasing the resistive load (mass) by doubling the moment of inertia of the wrist and fingers is consistent with neural evidence concerning bilateral symmetrical movements. Studies reporting facilitative bilateral effects argue that such interlimb coupling may reduce the intracortical inhibition received in the damaged hemisphere (Hummel & Cohen, 2006; Lacroix et al., 2004; Swinnen et al. 2002; Ward, 2005a, 2005b; Wenderoth et al., 2004). Specifically, executing unilateral movements of the impaired hand generates high interhemispheric inhibition targeting the motor cortex in the damaged hemisphere whereas when both limbs move simultaneously balanced interhemispheric interactions tend to normalize inhibitory influences subsequently improving motor control (Cauraugh & Summers, 2005; Duque et al., 2005; Ferbert et al., 1992; Floel et al., 2004; Murase et al., 2004; Ward, 2005a). Additional bilateral coordination evidence comes from structural investigations of the corpus callosum (Johansen-Berg et al., 2007; Wahl et al., 2007). Johansen-Berg et al. reported that bilateral coordination is strongly associated with the integrity of the white matter in the corpus callosum and such integrity generates interhemispheric pathways to the caudal cingulate motor area and supplementary motor area (Johansen-Berg et al., 2007). A leading question concerns interlimb coupling and interhemispheric interactions when the moment of inertia on one limb is doubled. Does doubling the moment of inertia of the hand on the unimpaired side facilitate the behavioral indications of balanced interhemispheric interactions evidenced during interlimb coupling movements?

Thus, the present study determined the effect of coupled bilateral training and doubled moment of inertia of the hand in chronic stroke patients by comparing the motor performance of three stroke groups that varied on the presence or absence of a resistive mass on the unimpaired hand: (1) coupled bilateral group with a load, (2) coupled bilateral group with no load, and (3) control (no active stimulation or load). Consistent with previous protocols, the two coupled bilateral groups received supplemental active neuromuscular stimulation on the impaired arm while the unimpaired limb performed the same movement in-phase (Cauraugh & Kim, 2002).

Two primary behavioral stroke motor recovery hypotheses based on balanced interhemispheric interactions and stability in the system from the doubled moment of inertia were tested: (1) the coupled bilateral load and no load groups will improve motor capabilities (i.e., more blocks moved, faster reaction times, and more regularity in the sustained contraction task) in comparison to the control group, and (2) the coupled bilateral load group will improve motor capabilities more than the coupled bilateral no load group.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

Thirty chronic stroke patients were recruited and the descriptive characteristics are displayed in Table 1. The average age was 67.23 years (SD = 10.25) and average post stroke time was 4.82 years (SD = 3.23). Admission criteria for the initial rehabilitation protocol included: (1) diagnosis of no more than two strokes; (2) a lower limit of 10° of voluntary wrist/fingers extension from an 80° wrist flexed position; (3) absence of other neurological deficits; and (4) currently not participating in another upper extremity rehabilitation program. All subjects read and signed an approved Institutional Review Board informed consent before testing began.

Table 1.

Summary characteristics of the three treatment groups

| Group | Gender | Mean age in years (SD) | Mean years post stroke (SD) | Lesion location: Hemisphere | Mean number of strokes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Females = 2 | 66.13 (13.96) | 3.39 (2.87) | Left = 2 | 1.3 |

| Males = 7 | Right = 7 | ||||

| Bilateral: No Load | Females = 3 | 67.18 (8.88) | 4.95 (3.63) | Left = 5 | 1.7 |

| Males = 7 | Right = 5 | ||||

| Bilateral: Load | Females = 5 | 68.38 (7.91) | 6.12 (3.19) | Left = 5 | 1.2 |

| Males = 5 | Right = 5 | ||||

| Totals | Females = 10 | 67.23 (10.25) | 4.82 (3.23) | Left = 12 | 1.4 |

| Males = 19 | Right = 17 |

Note: One control subject did not complete the training sessions and was not included in any analyses.

2.2. Procedures

2.2.1. Behavioral treatment groups

Subjects were randomly assigned to one of the three treatment groups (N = 10/group) that varied by the presence or absence of an extra load on the unimpaired hand, and whether they received active neuromuscular stimulation. All subjects attempted to perform wrist and finger extension movements.

In the coupled bilateral load group, subjects wore a weighted glove that doubled the moment of inertia load of each individual's unimpaired hand. Calculation of each subject's moment of inertia of her/his hand was based on an anatomical segment method that took into consideration bodyweight and measurements of the wrist and hand. The average mass added to the hand for the coupled bilateral load group equaled 912 g. The control group did not receive any additional load while attempting to perform unilateral movements.

2.2.2. Active neuromuscular stimulation

Both coupled bilateral groups, load and no load, received assistance during movement attempts in the form of active neuromuscular stimulation. The EMG-triggered neuromuscular stimulation was provided by surface electrodes attached to the wrist/fingers extensor muscles: extensor communis digitorum and extensor carpi ulnaris. A Neuromove microprocessor unit (Zynex, Denver, CO) provided the stimulation according to seven standardized settings: (1) an initial threshold level of 50 μV; (2) 1 second ramp up; (3) 5 seconds of biphasic stimulation at 50 Hz; (4) 15 to 29 mA stimulation range; (5) pulse width of 200 μs; (6) 1 second ramp down; and (7) 25 seconds of rest between trials. When the EMG activity consistently achieved the target threshold the unit automatically increased the threshold for the next trial. If patients were unable to generate enough wrist/fingers muscle activity to reach the criterion, then the unit automatically lowered the threshold slightly. During each training session, subjects completed 90 successful movement trials in approximately 90 minutes according to treatment group assignments. Across four separate days over a 2-week period, subjects completed a total of 360 trials.

In contrast, the control group completed four days of typical unilateral movement attempts on the impaired limb as a rehabilitation treatment. They did not receive any assistance during movement attempts from either active neuromuscular stimulation or bilateral movements. Further, wrist and finger extension movements were performed without a weighted glove on the unimpaired hand.

2.2.3. Outcome measures

One outcome measure, the Box and Blocks test, evaluated upper extremity motor capabilities by comparing the number of blocks moved on the pretest (baseline) to the posttest (within 2 days after completing training). The 60 second functional manual dexterity task assessed the ability of stroke patients to reach for and grasp a small block of wood (2.54 cm cube), lift the block over a short barrier in the center of the box, release it on the other side, and return to the original compartment to reach/grasp another block. A separate analysis contrasted the mean ratios of the number of blocks moved by the impaired and unimpaired arms/hands.

Additional outcome measures involved two types of force production by the wrist and finger extensor muscles: (1) rapid muscle onset in a reaction time task, and (2) deliberate muscle onset in a sustained contraction task (Cauraugh & Kim, 2002; Cauraugh & Kim, 2003a; Cauraugh et al., 2000). Subjects executed isometric wrist and finger extension movements against 34.09 kg load cells attached to customized platforms located directly in front of them.

In the simple reaction time task, subjects reacted to the onset of an auditory stimulus [1 kHz 80 dB (A)] by lifting the wrist and fingers against cushioned platforms located beneath the load cells. Ten trials each were administered to the impaired and unimpaired limbs alone and both limbs together. The foreperiod interval between the ready command and auditory stimulus onset varied randomly between 500 and 3000 milliseconds. Group assignment was blinded to evaluators during the pretest and posttest assessments.

In the sustained muscle contraction task, patients deliberately increased their wrist/fingers extension force to a maximal isometric contraction and maintained that level for 8 seconds. For each limb alone and both limbs together, three force production trials were administered. The two force generation tasks were counterbalanced across subjects and test sessions.

Prior to beginning testing, the height of the two load cells embedded in cushioned platforms were altered to accommodate individual hand sizes. In addition, EMG surface electrodes (silver-silver chloride electrodes, 1 cm in diameter and 2 cm apart with an epoxy-mounted preamplifier) were placed over the extensor communis digitorum and extensor carpi ulnaris muscles of the left and right arms. Upper limb EMG (band-pass filter 1–500 Hz) and force data were amplified by 5–20 K and collected at 1000 Hz via Biopac software (3.8.1, Biopac Systems Inc, Goleta, CA, USA). Force production and EMG activity were recorded online and analyzed offline. A custom Labview program controlled trial onset/offset and auditory stimulus presentation (National Instruments, TX, USA).

2.3. Data reduction

Intermediate calculations of the Box and Blocks data provided two perspectives of motor capabilities: impaired limb alone and ratio of impaired limb divided by the unimpaired limb. Intermediate reaction time calculations from the rectified and smoothed EMG, and force onset data (Botwinick & Thompson, 1966a, 1966b; Cauraugh & Kim, 2002) produced two median outcome measures. Specifically, fractionated total reaction time created a central component known as premotor reaction time and a peripheral component known as motor reaction time. Premotor reaction time defined the time from stimulus onset until the EMG activity of the extensor muscles exceeded double the EMG baseline value whereas motor reaction time started directly after premotor time and ended with movement initiation as the force amplitude exceeded double the force baseline value (Botwinick & Thompson, 1966a, 1966b; Cauraugh & Kim, 2002).

For the sustained contraction task, maintaining a maximum level of force was indexed by an overall measure of force production across an 8-second interval. To allow for the deliberate increase to peak force as well as the tendency to drop off near the end of the 8-second interval, force output calculations focused on the central 5 second segment, 1.5 seconds after stimulus onset and 1.5 seconds before the end of the sustained contraction. These data were analyzed with median force, an overall measure of sustained performance, and the coefficient of variation (CV). Additionally, the structure in the variability of force contractions were analyzed with approximate entropy (ApEn), a regularity and complexity measure.

In a pretest-posttest control group design, data from each outcome measure were submitted to separate mixed design analyses of variance (ANOVAs). Group × Test Session (3 × 2) mixed design ANOVAs compared group performances across time (i.e., baseline to post treatment) with alpha set at 0.05 for all statistical tests. Further, Greenhouse and Geisser's conservative degrees of freedom adjustment accommodated significant findings that violated the ANOVA sphericity assumption (Greenhouse & Geisser, 1959; Winer et al., 1991). When appropriate, post hoc mean comparisons were submitted to Tukey-Kramer's procedure.

3. Results

Given the multiple outcome measures, we selected the Box and Blocks test of motor capability as our primary outcome measure and fractionated motor reaction time as our secondary outcome measure. A third behavioral measure, median force represented the amount of force produced during the sustained contraction task.

3.1. Box and blocks test: Number of blocks moved

Originally, we intended to analyze the number of blocks moved with a 3 × 2 (Group × Test Session) ANOVA with repeated measures on test session. However, closely examining the pretest values for each treatment group revealed baseline differences among the groups. Thus, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was conducted to determine if the adjusted mean performances on the posttest differentiated the treatment groups, (F(2, 25) = 7.61; P < 0.004). As shown in Table 2, panel A, the ANCOVA indicated that both coupled bilateral groups moved more blocks than the control group, although, the two coupled bilateral groups (no load and load) were equivalent post-treatment.

Table 2.

| Panel A. Covariate analysis summary of mean (SE) number of blocks moved by the impaired limb as a function of treatment group and test session. The pretest values represent the covariate and the two sets of values on the posttest are (a) original means and (b) adjusted means. SE = standard error of the mean | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Number of blocks moved |

|||||

| Pretest |

Posttest |

|||||

| Covariate |

Original |

Adjusted |

||||

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | |

| Control | 20.00 | 6.69 | 19.11 | 6.18 | 22.54 | 1.58 |

| Bilateral: No load | 24.70 | 6.36 | 29.90 | 5.62 | 28.96 | 1.49 |

| Bilateral: Load | 26.00 | 6.63 | 32.80 | 6.91 | 30.65 | 1.49 |

| Panel B. Covariate analysis summary values for the ratio of the number of blocks moved by the impaired arm divided by the unimpaired arm | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Number of blocks moved |

|||||

| Pretest |

Posttest |

|||||

| Covariate |

Original |

Adjusted |

||||

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | |

| Control | 0.338 | 0.101 | 0.279 | 0.083 | 0.361 | 0.039 |

| Bilateral: No load | 0.478 | 0.116 | 0.520 | 0.096 | 0.489 | 0.037 |

| Bilateral: Load | 0.492 | 0.125 | 0.627 | 0.117 | 0.584 | 0.037 |

To further quantify the manual dexterity improvements evidence, Cohen's d formula indicated a large effect size (1.82) (Cohen, 1988). In addition, the reliable interaction showed a high average probability of replication (0.92) (Cumming & Maillardet, 2006; Killeen, 2005).

A converging operations analysis of motor improvements of the coupled bilateral treatment groups involved analyzing the ratio of number of blocks moved with the impaired limb divided by the number moved by the unimpaired limb. Consistent with the above analysis for the number of blocks moved, the ratio values were submitted to an ANCOVA. The analysis revealed a higher ratio for the coupled bilateral load group when compared to the control group, (F(2, 25) = 8.50; P < 0.03; probability of replication = 0.94). In addition, the coupled bilateral no load group was marginally better (P = 0.07) than the control group on the adjusted means. Table 2, panel B, displays the group mean ratios and standard error of the means (SEM) for the covariate, original, and adjusted values. Cohen's effect size formula revealed a large effect (d = 2.01).

3.2. Simple reaction time task: Fractionated reaction time components

Analysis of the two fractionated reaction time components, premotor and motor reaction times, included arm condition as a third factor. Arm condition referred to the impaired arm and two levels of procedural testing: impaired arm alone and impaired arm simultaneously moving with the unimpaired arm. Thus, the mixed design analysis included Group × Test Session × Arm Condition (3 × 2 × 2) ANOVA with repeated measures on test session and arm condition.

3.2.1. Premotor reaction time

Analysis of the central component of reaction time revealed a significant test session main effect, (F(1, 26) = 6.92; P < 0.02). Across the three groups and two arm conditions, median premotor reaction times decreased from the pretest (M = 214 ms, SE = 6.2) to the posttest (M = 198 ms, SE = 6.9).

3.2.2. Motor reaction time

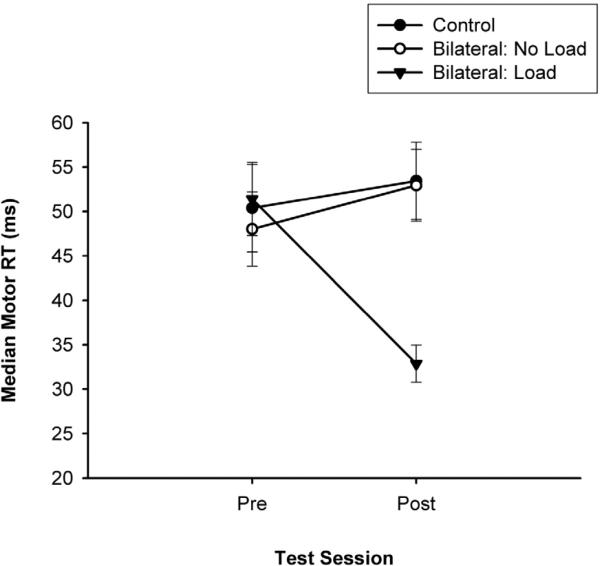

The three-way mixed design ANOVA on the median peripheral reaction time component indicated a reliable Group × Test Session interaction, (F(2, 26) = 6.91; P < 0.004). Follow-up analysis on the two-way interaction (see Fig. 1) revealed improved motor reaction times for the coupled bilateral load group on the posttest in comparison to the pretest. Further, the coupled bilateral load group was significantly faster on the posttest than the coupled bilateral no load group and control group. Cohen's effect size calculation indicated a large effect (d = 1.00) and the probability of replication equaled 0.89.

Fig. 1.

Median and SE bars for the fractionated motor reaction times as a function of treatment group by test session.

3.3. Sustained contraction task: Median force, CV, and ApEn

Force production data from the sustained contraction task were analyzed with median force, CV, and ApEn. Consistent with the fractionated RT components, the force production analysis involved separate mixed design 3 × 2 × 2 (Group × Test Session × Arm Condition) ANOVAs with repeated measures on the second and third factors. Table 3 contains the group by test session means and standard error values for each of the three sustained contraction task outcome measures.

Table 3.

Median force, coefficient of variation, and approximate entropy (SE) as a function of treatment group by test session. SE = standard error of the mean

| Group | Median force |

Median coefficient of variation |

Median approximate entropy |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretest |

Posttest |

Pretest |

Posttest |

Pretest |

Posttest |

|||||||

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | |

| Control | 5.0139 | 0.6236 | 4.3956 | 0.5906 | 15.8294 | 2.4638 | 11.0352 | 0.8301 | 0.1062 | 0.0110 | 0.1327 | 0.0147 |

| Bilateral: No Load | 6.4794 | 0.9071 | 5.7965 | 0.5605 | 13.5022 | 1.3018 | 15.5530 | 2.1532 | 0.1411 | 0.0213 | 0.1107 | 0.0100 |

| Bilateral: Load | 3.9536 | 0.4336 | 4.1655 | 0.2746 | 10.1956 | 1.0125 | 8.3455 | 0.6987 | 0.1917 | 0.0139 | 0.1517 | 0.0106 |

3.3.1. Median force

Analysis of the median force data produced during the sustained contraction task revealed a significant arm condition main effect (F(1, 27) = 4.55; P < 0.043. This finding represented a small effect size (d = 0.14) with a probability of replication = 0.54. Across the three groups, the impaired limb alone arm condition (M = 5.16 kg, SE = 0.27) generated a slightly higher force output than the impaired limb moving simultaneously with the unimpaired limb (M = 4.77 kg, SE = 0.28).

3.3.2. Coefficient of variation (CV)

Median CV scores were calculated and analyzed to ensure that variability was normalized to the magnitude of the corresponding absolute force value (i.e., CV = SD/mean force). The analysis identified a significant two-way interaction in the CV data, (F(2, 27) = 5.04; P < 0.03; probability of replication = 0.58). The large effect size (d = 0.94) interaction is shown in Table 3. Follow-up analysis revealed that the coupled bilateral load group displayed a reduction in CV from pretest to posttest, and this group displayed less CV than the two other groups across the arm conditions.

3.3.3. Approximate entropy (ApEn)

The fifth dependent variable to examine the structure of the variability in the sustained force output task was median ApEn; a time dependent regularity measure that quantifies the unpredictability of force production (Newell et al., 2001; Vaillancourt & Newell, 2002). Preliminary analysis of ApEn indicated numerous violations of the assumption of normality, thus, the data were transformed with a square root function to achieve normality. Mixed design analysis of the transformed median ApEn indicated a significant Group × Test Session interaction (F(2, 25) = 3.89; P < 0.04; probability of replication = 0.65). As shown in Table 3, the coupled bilateral load group significantly reduced ApEn across the test sessions. As ApEn approaches zero, more regularity and less complexity in the signal is evidenced. Such an increased regularity pattern was demonstrated by the coupled bilateral load and no load groups, but follow-up procedures failed to confirm more regularity in the coupled bilateral no load group's posttest session. Further, Cohen's d analysis of the ApEn two-way interaction indicated a moderate effect size (0.57).

4. Discussion

Collectively, the present behavioral findings support and extend the neural hypothesis. Consistent with the argument that bilateral coordinated movements reduce intracortical inhibition in the damaged hemisphere, the coupled bilateral load and no load groups improved motor capabilities across the test sessions. Indeed, the behavioral results of the simultaneous interlimb coupling treatment interventions appear to induce balanced interhemispheric interactions with and without the doubled moment of inertia on the unimpaired limb. Supporting evidence comes from the two sets of Box and Blocks results, faster motor reaction times, a reduction in CV, and more signal regularity (less complexity). The impaired limb of the coupled bilateral load group demonstrated patterns of improved motor control that strongly suggest normalized inhibitory effects. Similar improvements highlighted the motor performances of the coupled bilateral no load group in comparison to the control group.

Structural support for the neural hypothesis includes three critical areas: supplementary motor area, corpus callosum, and crossed corticospinal axons (Cauraugh & Summers, 2005; Goldberg, 1985; Stinear et al., 2007; Summers et al., 2007). Each structure is highly involved during the execution of bilateral movements. Indeed, the supplementary motor area is viewed as the source for initiating and controlling bilateral movements and interlimb coupling. [See separate recent (2005) reviews by Cauraugh and Summers, and Carson.] Moreover, motor control improvements are associated with an intact somatosensory system. This evidence comes from studies that investigated peripheral nerve stimulation on both healthy and stroke impaired subjects; findings indicated an increased activation of the contralateral primary sensorimotor cortex (Celnik et al., 2007; Golaszewski et al., 2004; Smania et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2005). Our behavioral results present convincing stroke motor recovery evidence that elegantly supplements the consensus conclusions drawn primarily from studies of bimanual coordination theory.

Further, the current improved motor capabilities in the impaired limb reflect neural plasticity. Recently, Hummel and Cohen (Hummel & Cohen, 2005) reviewed how neural plasticity of the adult and injured brain represents continual learning based on experiences. A post stroke adapting brain is evidenced by multiple means: motor practice, noninvasive cortical stimulation, and altered afferent input. These neural plasticity principles were further elaborated by Wolpaw and Carp (Wolpaw & Carp, 2006). Most importantly, two of the three neural plasticity principles (i.e., motor practice and altered afferent input) were inherent in the present study.

The current findings of improved motor capabilities in chronic stroke patients replicate and extend the results of previous studies using coupled bilateral protocols (Cauraugh & Kim, 2002; Cauraugh & Kim, 2003a; Cauraugh, Kim, & Duley, 2005). Specifically, combining active neuromuscular stimulation on the impaired limb with bilateral symmetrical movements on the unimpaired limb with or without a doubled moment of inertia produced improved motor capabilities on the impaired upper extremity. Indeed, functional movements involving voluntary control of the wrist and finger extensor muscles are evidenced in both coupled bilateral groups with higher numbers of blocks moved post treatment. Moreover, the coupled bilateral load group demonstrated improved voluntary capabilities as well as new findings across multiple outcome measures. Reliable two-way interactions provide three new findings of the benefit of coupled bilateral training with an increased load on the unimpaired limb by showing improved performance across the test sessions (1) faster motor reaction times, (2) less CV, and (3) reduced ApEn on the posttest in comparison to the pretest. This increased regularity in the coupled bilateral load group on the sustained contraction task indicates less complexity in the force output signal.

Collectively, the present findings are consistent with the notion of bilateral movements and symmetrical stability. Earlier chronic stroke evidence indicates more stability when bilateral arm movements are performed either with or without an extra load than when unilateral movements are performed on the impaired limb (Cesari & Newell, 2000). Cunningham et al. reported an increase in smoothness and velocity profiles in the impaired limb during bilateral elbow extension with an added moment of inertia (Cunningham et al., 2002). In addition, faster movement times were found by Rose and Winstein during bilateral movements in comparison to unilateral movements post stroke (Rose & Winstein, 2004, 2005). Similarly, Harris-Love et al., identified an advantage in chronic stroke patients during arm reaching movements when interlimb coupling was required (Harris-Love et al., 2005). Symmetrical movements performed simultaneously with both arms improved peak acceleration and velocity profiles.

In closing, our behavioral evidence is consistent with a neural explanation in that simultaneously moving both limbs during stroke rehabilitation training appears to activate balanced interhemispheric interactions under two conditions: (1) when bilateral movements are combined with active neuromuscular stimulation on the impaired limb, and (2) even when an extra load is added to the unimpaired limb for stability. The two coupled bilateral groups excelled on multiple outcome measures across test sessions and in comparison to the control group. Our coupled bilateral training effects that accrued in 6 hours of treatment intervention are worthy of being considered by rehabilitation specialists as potential treatment options (Cauraugh & Kim, 2003b; Cauraugh et al., 2008; Kreisel et al., 2006; Kreisel et al., 2007).

Acknowledgments

JHC was supported by grants from the American Heart Association and National Institutes of Health. SAC was supported by a grant from the American Heart Association. JJS was supported by awards from the Australian Research Council and the Australian Health Management Group – Medical Research Fund.

References

- Botwinick J, Thompson LW. Components of reaction time in relation to age and sex. J Genet Psychol. 1966a;108(2d Half):175–183. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1966.10532776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botwinick J, Thompson LW. Premotor and motor components of reaction time. J Exp Psychol. 1966b;71(1):9–15. doi: 10.1037/h0022634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson RG. Neural pathways mediating bilateral interactions between the upper limbs. Brain Research Reviews. 2005;49(3):641–662. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauraugh JH. Coupled rehabilitation protocols and neural plasticity: upper extremity improvements in chronic hemiparesis. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2004;22(35):337–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauraugh JH, Kim S. Two coupled motor recovery protocols are better than one: electromyogram-triggered neuromuscular stimulation and bilateral movements. Stroke. 2002;33(6):1589–1594. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000016926.77114.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauraugh JH, Kim SB. Chronic stroke motor recovery: duration of active neuromuscular stimulation. J Neurol Sci. 2003a;215(12):13–19. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(03)00169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauraugh JH, Kim SB. Stroke motor recovery: active neuromuscular stimulation and repetitive practice schedules. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003b;74(11):1562–1566. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.11.1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauraugh JH, Kim SB, Duley A. Coupled bilateral movements and active neuromuscular stimulation: intralimb transfer evidence during bimanual aiming. Neurosci Lett. 2005;382(12):39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauraugh JH, Kim SB, Summers JJ. Chronic stroke longitudinal motor improvements: cumulative learning evidence found in the upper extremity. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;25(12):115–121. doi: 10.1159/000112321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauraugh JH, Light K, Kim SB, Thigpen M, Behrman A. Chronic motor dysfunction after stroke: recovering wrist and finger extension by electromyography-triggered neuromuscular stimulation. Stroke. 2000;31(6):1360–1364. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.6.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauraugh JH, Summers JJ. Neural plasticity and bilateral movements: A rehabilitation approach for chronic stroke. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;75(5):309–320. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celnik P, Hummel F, Harris-Love M, Wolk R, Cohen LG. Somatosensory stimulation enhances the effects of training functional hand tasks in patients with chronic stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(11):1369–1376. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesari P, Newell KM. Body-scaled transitions in human grip configurations. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 2000;26(5):1657–1668. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.26.5.1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming G, Maillardet R. Confidence intervals and replication: where will the next mean fall? Psychol Methods. 2006;11(3):217–227. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.3.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CL, Stoykov ME, Walter CB. Bilateral facilitation of motor control in chronic hemiplegia. Acta Psychol (Amst) 2002;110(23):321–337. doi: 10.1016/s0001-6918(02)00040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duque J, Hummel F, Celnik P, Murase N, Mazzocchio R, Cohen LG. Transcallosal inhibition in chronic subcortical stroke. Neuroimage. 2005;28(4):940–946. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferbert A, Vielhaber S, Meincke U, Buchner H. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in pontine infarction: correlation to degree of paresis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1992;55(4):294–299. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.4.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floel A, Nagorsen U, Werhahn KJ, Ravindran S, Birbaumer N, Knecht S, et al. Influence of somatosensory input on motor function in patients with chronic stroke. Ann Neurol. 2004;56(2):206–212. doi: 10.1002/ana.20170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golaszewski SM, Siedentopf CM, Koppelstaetter F, Rhomberg P, Guendisch GM, Schlager A, et al. Modulatory effects on human sensorimotor cortex by whole-hand afferent electrical stimulation. Neurology. 2004;62(12):2262–2269. doi: 10.1212/wnl.62.12.2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg G. Supplementary motor area structure and function: review and hypotheses. Behav Brain Sci. 1985;8:567–616. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhouse SW, Geisser S. On methods in the analysis of profile data. Pyschometrika. 1959;25:95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Love ML, McCombe Waller S, Whitall J. Exploiting interlimb coupling to improve paretic arm reaching performance in people with chronic stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(11):2131–2137. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel FC, Cohen LG. Drivers of brain plasticity. Curr Opin Neurol. 2005;18(6):667–674. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000189876.37475.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel FC, Cohen LG. Non-invasive brain stimulation: a new strategy to improve neurorehabilitation after stroke? Lancet Neurol. 2006;5(8):708–712. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70525-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen-Berg H, Della-Maggiore V, Behrens TE, Smith SM, Paus T. Integrity of white matter in the corpus callosum correlates with bimanual co-ordination skills. Neuroimage. 2007;36(Suppl 2):T16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killeen PR. An alternative to null-hypothesis significance tests. Psychol Sci. 2005;16(5):345–353. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.01538.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreisel SH, Bazner H, Hennerici MG. Pathophysiology of stroke rehabilitation: temporal aspects of neurofunctional recovery. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2006;21(12):6–17. doi: 10.1159/000089588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreisel SH, Hennerici MG, Bazner H. Pathophysiology of stroke rehabilitation: the natural course of clinical recovery, use-dependent plasticity and rehabilitative outcome. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;23(4):243–255. doi: 10.1159/000098323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix S, Havton LA, McKay H, Yang H, Brant A, Roberts J, et al. Bilateral corticospinal projections arise from each motor cortex in the macaque monkey: a quantitative study. J Comp Neurol. 2004;473(2):147–161. doi: 10.1002/cne.20051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murase N, Duque J, Mazzocchio R, Cohen LG. Influence of interhemispheric interactions on motor function in chronic stroke. Ann Neurol. 2004;55(3):400–409. doi: 10.1002/ana.10848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell KM, Liu YT, Mayer-Kress G. Time scales in motor learning and development. Psychol Rev. 2001;108(1):57–82. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose DK, Winstein CJ. Bimanual training after stroke: are two hands better than one? Top Stroke Rehabil. 2004;11(4):20–30. doi: 10.1310/NCB1-JWAA-09QE-7TXB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose DK, Winstein CJ. The co-ordination of bimanual rapid aiming movements following stroke. Clin Rehabil. 2005;19(4):452–462. doi: 10.1191/0269215505cr806oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smania N, Montagnana B, Faccioli S, Fiaschi A, Aglioti SM. Rehabilitation of somatic sensation and related deficit of motor control in patients with pure sensory stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84(11):1692–1702. doi: 10.1053/s0003-9993(03)00277-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinear CM, Barber PA, Smale PR, Coxon JP, Fleming MK, Byblow WD. Functional potential in chronic stroke patients depends on corticospinal tract integrity. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 1):170–180. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers JJ, Kagerer FA, Garry MI, Hiraga CY, Loftus A, Cauraugh JH. Bilateral and unilateral movement training on upper limb function in chronic stroke patients: A TMS study. J Neurol Sci. 2007;252(1):76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinnen SP, Debaere F, Puttemans V, Vangheluwe S, Kiekens C. Coordination deficits on the ipsilesional side after unilateral stroke: the effect of practice on nonisodirectional ipsilateral coordination. Acta Psychol (Amst) 2002;110(23):305–320. doi: 10.1016/s0001-6918(02)00039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinnen SP, Wenderoth N. Two hands, one brain: cognitive neuroscience of bimanual skill. Trends Cogn Sci. 2004;8(1):18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2003.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillancourt DE, Newell KM. Changing complexity in human behavior and physiology through aging and disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2002;23(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00247-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl M, Lauterbach-Soon B, Hattingen E, Jung P, Singer O, Volz S, et al. Human motor corpus callosum: topography, somatotopy, and link between microstructure and function. J Neurosci. 2007;27(45):12132–12138. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2320-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward NS. Neural plasticity and recovery of function. Prog Brain Res. 2005a;150:527–535. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(05)50036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward NS. Plasticity and the functional reorganization of the human brain. Int J Psychophysiol. 2005b;58(23):158–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenderoth N, Debaere F, Sunaert S, van Hecke P, Swinnen SP. Parieto-premotor areas mediate directional interference during bimanual movements. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14(10):1153–1163. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitall J, McCombe Waller S, Silver KH, Macko RF. Repetitive bilateral arm training with rhythmic auditory cueing improves motor function in chronic hemiparetic stroke. Stroke. 2000;31(10):2390–2395. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.10.2390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer B, Brown D, Michels K. Statistical Principles in Experimental Design. 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wolpaw JR, Carp JS. Plasticity from muscle to brain. Prog Neurobiol. 2006;78(35):233–263. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CW, van Gelderen P, Hanakawa T, Yaseen Z, Cohen LG. Enduring representational plasticity after somatosensory stimulation. Neuroimage. 2005;27(4):872–884. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]