Abstract

Placental abnormalities occur frequently in cloned animals. Here, we attempted to isolate trophoblast stem (TS) cells from mouse blastocysts produced by somatic cell nuclear transfer (NT) at the blastocyst stage (NT blastocysts). Despite the predicted deficiency of the trophoblast cell lineage, we succeeded in isolating cell colonies with typical morphology of TS cells and cell lines from the NT blastocysts (ntTS cell lines) with efficiency as high as that from native blastocysts. The established 10 ntTS cell lines could be maintained in the undifferentiated state and induced to differentiate into several trophoblast subtypes in vitro. A comprehensive analysis of the transcriptional and epigenetic traits demonstrated that ntTS cells were indistinguishable from control TS cells. In addition, ntTS cells contributed exclusively to the placenta and survived until term in chimeras, indicating that ntTS cells have developmental potential as stem cells. Taken together, our data show that NT blastocysts contain cells that can produce TS cells in culture, suggesting that proper commitment to the trophoblast cell lineage in NT embryos occurs by the blastocyst stage.

Keywords: DNA methylation, epigenetics, blastocyst, cloned animals, placenta

Mammalian embryos produced by nuclear transfer (NT) have limited developmental potential. In the mouse, about half of NT embryos develop to blastocysts in vitro (1), but most NT embryos die during the early postimplantation stage (2–6) along with growth arrest of extraembryonic tissues (7). Interestingly, NT mouse embryos that reach term commonly have an unusually large placenta (placentomegaly) associated with overgrowth of the spongiotrophoblast layer (2, 5). Other types of placental abnormalities also occur in cloned cattle (8–10) and sheep (11, 12), suggesting that the abnormality in the trophoblast cell lineage is an inevitable outcome of animal cloning by somatic cell NT.

In mammals, placental development begins at the blastocyst stage when trophoblast cells are first formed. The trophoblast cell lineage is first segregated as the trophectoderm, which is set aside from the embryonic inner cell mass (ICM) lineage. In the mouse, the stem cell population of the trophoblast cell lineage proliferates for at least a few days after implantation and produces the source of all trophoblastic components of the chorioallantoic placenta (13). The stem cells of the trophoblast cell lineage can be isolated and maintained as trophoblast stem (TS) cell lines by in vitro culture (14, 15).

NT technology has been used to produce embryonic stem (ES) cells (ntES cells). These ntES cells show similar transcriptome and DNA methylation profiles to those of authentic ES cells and contribute to all tissues except the placenta (16). In contrast, the production of TS cells from NT embryos has not been reported. Because NT conceptuses commonly show abnormalities of the placenta, it is suspected that the commitment or function of the trophoblast cell lineage is compromised in NT embryos. In the present study, we established TS cell lines from NT blastocysts (ntTS cells) to address this issue. We then characterized the successfully derived ntTS cells to determine whether nuclear cloning affects the trophoblast cell lineage.

Results

TS cells can be isolated from mouse blastocysts in conditions that included FGF4 (14, 15). We applied this method to examine whether NT embryos can produce propagatable TS cells. Among the 465 reconstructed oocytes, which were enucleated and injected with the cumulus cell nuclei of (C57BL/6 × DBA/2)F1 (BDF1) mice, 113 embryos developed to blastocysts with apparent blastocoel formation (NT blastocysts) (Table 1). Of these NT blastocysts, 96 attached and formed outgrowths. The TS-like colonies that appeared after the dissociation of the outgrowth were designated as P1. In total, 63 cultures (55.8% of blastocysts) produced P1 colonies, a frequency that was comparable with, but not more efficient than, the frequency in controls (58.3%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

TS colony derivation

| Survived | Activated | Blastocyst | Adhered (% of blastocyst) | P1 colony (% of blastocyst) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDF1 control TS | NA | NA | 24 | 22 | (91.7) | 14 | (58.3) |

| BDF1 ntTS | 465 | 418 | 113 | 96 | (85.0) | 63 | (55.8) |

NA: not applicable.

From the 10 randomly chosen P1 cultures, 5 TS-like cell lines were established and designated as BDntTS (#1–#5) or ntTS cell lines. Similarly, 2 control TS cell lines were established from 8 P1 cultures (BDTS#1 and -#2). All ntTS cell lines showed the typical morphology of TS cells, including the formation of epithelial cell-like colonies under the stem condition [Fig. 1A, supporting information (SI) Fig. S1] (14), and had proliferation rates similar to those of the control TS cell lines (Fig. S1D). Removing the FGF4 and feeder cells decreased the proliferation rate of ntTS cells, and the cells began to differentiate and show dramatic morphological changes, behavior that was similar to that of the control TS cells (Fig. 1A, Fig. S1D). By the fourth day of differentiation, most ntTS cells showed trophoblast giant cell (TGC)-like morphology (Fig. 1A).

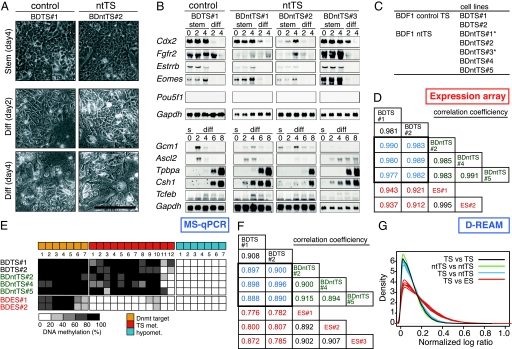

Fig. 1.

Normalcy of ntTS cell lines. (A) ntTS and TS (control) cell lines were cultured in the presence (stem, day 4) and absence (diff, day 2 and day 4) of FGF4 and MMC-EMFI conditioned medium. (Scale bar, 0.2 mm.) (B) Northern blot analysis of ntTS and TS cells in stem (s) and differentiation (diff) conditions. (C) Established cell lines. Asterisks (*) indicate the cell lines with mild aneuploidy. (D) Correlation coefficient of Affymetrix expression microarray intensity values among the ntTS and TS cell lines. (E) MS-qPCR using the primers for TS-specific methylation loci, unmethylated loci, and Dnmt target loci. (F) Correlation coefficient of D-REAM-normalized logMED values among the ntTS and TS cell lines. (G) Density plot of absolute variance in each single comparison. Note that the differences between ntTS and TS cell lines (blue lines) are similar to the difference between the 2 TS controls (black line).

The expression of marker genes for TS cells (Cdx2, Fgfr2, Esrrb, and Eomes) (13, 14) was detected in both ntTS and control TS cell lines in self-renewal conditions and was downregulated by the induction of differentiation (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1). The expression of all marker genes for differentiated trophoblast subtypes (Gcm1 and Tcfeb for labyrinthine trophoblast cells, Ascl2/Mash2 for diploid trophoblast cells, Tpbpa for spongiotrophoblast cells, and Csh1/Pl1 for TGCs) (14) was detected after the induction of differentiation, although the temporal expression patterns showed slight variation among the ntTS cell lines (Fig. 1B). In both stem and differentiation conditions, the expression of Pou5f1 (Oct3/4) and Hnf-4 (Fig. S1), the specific markers for the ES and endoderm cells, respectively (17, 18), was not detected, suggesting that these cell lines do not contain cells of the ICM or endoderm lineage. Karyotype analysis revealed that 3 ntTS and 2 control TS cell lines had euploid cells as the majority (≈60%), whereas 2 ntTS cell lines (BDntTS#1 and BDntTS#3) had aneuploid cells as the majority (Fig. 1C and Fig. S2).

To examine the global gene expression profile, the ntTS and TS cell lines were subjected to expression microarray analysis using the Mouse Genome 430 2.0 Array, which contains 45,101 unique probe sets. The results of cross-comparison showed no ntTS-common expression changes in the range of signal log ratio >1 or <–1 (Table S1). The correlation coefficient between ntTS and control TS cells was as high as that among controls (Pearson's correlation coefficient >0.97) (Fig. 1D). We concluded that the ntTS cell lines had similar gene expression profiles to those of the control TS cell lines.

In the NT embryos, diverse epigenetic abnormalities are observed at the cytogenetic and molecular levels in preimplantation embryos (19–21) and in the placenta at term (22). To elucidate whether the epigenetic errors exist in the ntTS cell lines, we examined the DNA methylation status of 3 euploid BDntTS and 2 BDTS cell lines. First, to confirm whether the cell type-specific DNA methylation pattern is established in ntTS cells, we analyzed the loci whose DNA methylation status had been determined previously (20) by DNA methylation-sensitive restriction-based quantitative PCR (MS-qPCR). We reported previously on the cell type-specific DNA methylation profiles for 10 cell types and tissues, in which the DNA methylation status of 200 loci has been identified (23, 24). Among them, we focused on 26 NotI loci in unique sequences, including the loci that were (i) methylated in TS but not in ES cells, (ii) hypomethylated in both TS and ES cells, and (iii) the targets of DNA methyltransferases in ES cells (25) (Table S2). The DNA methylation status of these loci did not show crucial differences between the ntTS and TS cell lines examined (Fig. 1E). Thus, the cell type-specific DNA methylation patterns of the loci examined in TS cell lines were recapitulated in the ntTS cells.

Next, we analyzed the DNA methylation profile using microarray-based genomewide, high-throughput DNA methylation analysis (D-REAM) (26). We processed and analyzed the genomic DNA from ntTS and TS cell lines using a custom tiling microarray, named the NotSAT array (Fig. S3, see SI Methods). Both the correlation coefficient and the distribution of the differential log ratios showed that the similarities between the ntTS and TS cell lines were close to those between the 2 control TS cell lines and among the ntTS cell lines (Fig. 1 F and G). A few loci that showed increased or decreased DNA methylation in the ntTS cell lines compared with control TS cell lines were observed but were not reproduced in the green fluorescent protein (GFP)-CD-1 background (described below), indicating that there was no ntTS-specific alteration of the DNA methylation status. Thus, the overall DNA methylation profile was faithfully reestablished in the DNA methylation levels in the ntTS cell lines.

The developmental potential of TS cells is shown by the exclusive contribution to the placenta formation in chimeras (14), which demonstrates the commitment to the trophoblast cell lineage. To address the potential of ntTS cells in vivo, additional TS and ntTS cell lines were derived from GFP-transgenic mice with CD-1 background (GFP-CD-1 mice), in which all cells express enhanced GFP from an integrated pCX-EGFP vector (27). Five ntTS (GFPntTS) and 2 control (GFPTS) cell lines were established with efficiencies similar to that of the BDF1 background. These GFPntTS cell lines also showed properties similar to those of the GFPTS, BDntTS, and BDTS cell lines (Figs. S4 and S5).

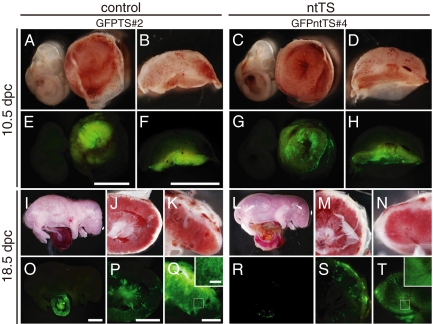

To construct the chimera embryos, GFPntTS or GFPTS cells were injected into blastocysts, transplanted into the foster mothers' uteri, and then recovered at 10.5 and 18.5 days post coitum (dpc). Both GFPntTS and GFPTS cells produced the chimeric embryos at similar frequencies (Table 2 and Fig. S4D and Table S3). At 10.5 dpc, derivative cells of 2 “near-euploid” GFPntTS (#2 and #4) and control GFPTS cells were observed in the placentas in chimeras at an equivalent frequency and appearance (Fig. 2 A–H, 10.5 dpc). GFP-positive cells in ntTS chimeras were also observed at 18.5 dpc, although the number of GFP-positive cells was slightly lower than that in the control chimeras (Fig. 2 I–T, 18.5 dpc). In contrast, GFPntTS cell lines with more severe aneuploidy did not show chimerism in 18.5-dpc embryos (Table 2). The control cell line GFPTS#1 had a low frequency of chimera formation, whereas a high contribution in a few chimeric placentas was observed. In both GFPntTS and GFPTS chimeras, the GFP-positive cells were distributed in all 3 layers of the placenta with no apparent bias to any specific layer (Fig. S4). In the 29 chimeric conceptuses in which the GFPntTS cells contributed to the placenta, no GFP-positive cells were found in tissues of ICM origin, including the extraembryonic mesoderm-derived umbilical cord (Fig. 2R). Taken together, these data confirmed that the ntTS cells contributed properly to all trophoblast layers in vivo but not to embryonic tissues, showing the correct commitment of their cell fate.

Table 2.

Contribution of ntTS and TS cells in the chimera

| Stage of recovery | Group | Cell line | Transferred (recipient) | Recovered | GFP positive (% of recovered) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10.5 dpc | Control TS | GFPTS#1 | 24 (2) | 2 | 1 | (50.0) |

| GFPTS#2 | 24 (2) | 10 | 7 | (70.0) | ||

| ntTS | GFPntTS#2 | 36 (3) | 22 | 10 | (45.5) | |

| (euploid) | GFPntTS#4 | 36 (3) | 13 | 9 | (69.2) | |

| 18.5 dpc | Control TS | GFPTS#1 | 33 (3) | 13 | 2 | (15.4) |

| GFPTS#2 | 36 (3) | 25 | 9 | (36.1) | ||

| ntTS | GFPntTS#2 | 67 (6) | 22 | 2 | (9.1) | |

| (euploid) | GFPntTS#4 | 44 (4) | 11 | 7 | (63.6) | |

| ntTS | GFPntTS#1 | 33 (3) | 21 | 0 | (0.0) | |

| (aneuploid) | GFPntTS#3 | 33 (3) | 13 | 1 | (7.7) | |

| GFPntTS#5 | 45 (4) | 21 | 0 | (0.0) | ||

| No injection | 12 (1) | 3 | ||||

Fig. 2.

Mutually exclusive contribution of GFPntTS cell lines to the placenta in chimeras: chimeric embryos with GFP-positive cells. Chimeric embryos were generated by the injection of GFPTS cells (Left) or GFPntTS cells (Right) into the diploid blastocysts. The reconstituted embryos were developed in the uteri of foster mothers and recovered at 10.5 dpc (A–H) and 18.5 dpc (I–T). Embryos were observed under bright field (A–D, I–N) and dark field with GFP luminescence (E–H, O–T). Cross sections (F, H, Q, and T) of placental tissue show the dispersed contribution of GFP-positive cells in the placenta. Note that no GFP-positive cells were observed in the embryo proper in the ntTS or control TS cells (E, G, O, and R). [Scale bars: 3 mm (E and F), 5 mm (O), 3 mm (P), 1 mm (Q), and 0.2 mm (inset).]

Discussion

Because of the variety and frequency of placental abnormalities in NT embryos (5, 7), it is expected that most NT blastocysts have an abnormal trophoblast cell lineage resulting, at least in part, from abnormalities in the lineage establishment. However, in this study, the successful derivation of TS colonies and cell lines from NT embryos under the culture condition used for TS cell isolation implies that putative stem cells of the trophoblast in NT blastocysts have a proliferative capacity similar to those in native blastocysts. In addition, ntTS cells could contribute to the trophoblast cell lineage and differentiate into trophoblast subtypes similar to the activities of the control TS cells in chimeras, suggesting that the stem cell population of the trophoblast cell lineage in NT embryos at the blastocyst stage has already been properly committed to the trophoblast cell fate. Accordingly, it is implicated that the defects in the trophoblast cell lineage of NT embryos are non-cell autonomous. Functional abnormality of trophoblast cells is a considerable cause of the peri-implantation lethality of NT embryos. It has been reported that this phenotype could be rescued partially by the injection of wild-type ES or ICM cells into NT blastocysts (28). In addition, Miki et al. have recently shown that embryonic tissues have more impact on the placental hyperplasia of NT conceptuses (29). Together with these reports, our results suggest that the abnormalities of trophoblast cell lineage in NT embryos/conceptuses are, at least in part, caused by disorganized interaction between extraembryonic and embryonic tissues.

The NT embryos probably have a tendency to produce more aneuploid cell lines than do normal embryos, implying the presence of a higher-order epigenetic abnormality besides DNA methylation status. When comparing strains, ntTS cell lines with a GFP-CD-1 background showed more severe aneuploidy than did cell lines with a BDF1 background. It is interesting to note in this context that the success rate of cloning with CD-1 mice is ultimately low (30). Surprisingly, even though ntTS cells have milder aneuploidy, the properties of these cells were not compromised much. Because the cells of tetraploid embryos can functionally replace the trophoblastic component of the placenta (31), the trophoblast cell lineage seems to have an innate tolerance against the chromosomal abnormality. Alternatively, the embryos from which the cell line with severe aneuploidy is derived may be the source of the early developmental defect and may be unable to produce ES cell lines (32). Although it is difficult to determine which stage the aneuploidy originated from, the relative nuclear stability of the BDF1 background may be associated with more successful cloning than in other genetic backgrounds.

Given that both the NT conceptuses that survive and those devoid of fetuses often show placental overgrowth (33), it is expected that ntTS cell lines would show common cell-autonomous abnormalities, which probably accompany several epigenetic errors (22, 34, 35). However, ntTS cells had a proliferation rate equivalent to that of the control TS cells in vitro (Fig. S1D) and in the chimeras showed an unbiased distribution to all 3 layers of the placenta (5). Together with the analysis of the global expression and DNA methylation profiles, these results suggest that, if it exists, any preexisting aberrant DNA methylation in NT embryos is erased or corrected in ntTS cells during the process of cell line establishment in vitro. Strikingly, DNA hypermethylation of the Sall3 locus, which has been observed commonly in the placentas of cloned offspring (34), was not observed in ntTS cells (Fig. S3E). In NT blastocysts, Cdx2 is stably expressed, whereas Pou5f1 expression often fails or decreases (36). Given that Cdx2 expression is sufficient for the transdifferentiation of ES cells to TS cells (37), Cdx2 protein may be capable of arranging the genomewide epigenetic status to be specific to TS cells by cooperating with other factors expressed in putative trophectoderm cells of NT embryos. On the other hand, an insufficient FGF4 supply from a defective ICM might compromise the maintenance of Cdx2 expression in NT embryos, presumably resulting in a “misprogrammed” stem cell population of trophoblast cell lineage and diverse placental defects in cloned animals.

In conclusion, despite the diverse developmental outcome of cloned embryos, particularly in the extraembryonic cell lineage, our results show that NT blastocysts contain cells that have the potential to produce TS cell lines indistinguishable from those from normal embryos in terms of their gene expression and DNA methylation profiles and their developmental potency in vivo. The normalcy of ntTS cells suggests that the cell-autonomous cues for the specification of TS cells in vivo are intact in NT blastocysts.

Materials and Methods

Production of Cumulus Cell Nuclear-Transferred Embryos.

Cloned embryos were produced at University of Hawaii using the “Honolulu method” as described elsewhere (2). In brief, the nuclei of cumulus cells from BDF1 female mice or the transgenic female mice that harbor a GFP gene expressed from a strong cytomegalovirus-chicken β-actin enhancer–promoter combination (GFP-CD-1 mice) were injected into enucleated BDF1 oocytes. The reconstituted embryos were allowed to develop for 72 h and then subjected to the selection of blastocysts for the establishment of TS cell lines.

Establishment of TS Cell Lines from Cumulus NT Blastocysts.

The NT blastocysts on day 4 (72 h) after activation were denuded with acid Tyrode's solution (pH 3), washed with M12, and then used for the TS cell isolation essentially as described elsewhere (14). Briefly, the NT blastocysts were cultured on mitomycin C-treated mouse embryonic fibroblast cells (MMC-EMFI) with TS culture medium [RPMI 1640 containing 20% FBS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco), 50 units/mL penicillin, 50 μg/mL streptomycin sulfate, and 0.1 μM 2-mercaptoethanol] supplemented with 37.5 ng/mL FGF4 (PeproTech) and 1.5 μg/mL heparin (Sigma) (TS + 1.5FH). After 24 h from the onset of outgrowth, the embryos were treated with trypsin/EDTA (0.05% trypsin/1 mM EDTA) to dissociate them into single cells and cultured, with the medium changed every 2 days. The colonies appearing in the culture wells, which were termed P1, were picked up mechanically and dispersed by trypsin/EDTA and then seeded on new MMC-EMFI with TS + 1.5FH. In both ntTS and control TS cell lines, 1 cell line was derived from 1 blastocyst.

In Vitro Differentiation of TS Cells and RNA Extraction.

Each TS cell line was seeded at different cell numbers on 100-mm culture dishes (Nunc) coated with 0.1% gelatin solution with TS medium containing 80% MMC-EMFI conditioned medium supplemented with growth factors (80CM + 1.5FH). Cells were seeded at approximate concentrations of 1 × 106, 5 × 105, 2 × 105, 5 × 105, 1 × 105, 5 × 104, and 5 × 104 cells per 100-mm culture dish to prepare stem cells (days 0, 2, and 4) and differentiated cells (days 2, 4, 6, and 8). The day of seeding was designated day –2, and the day of the first medium exchange was day 0. The medium was changed every 2 days with fresh 80CM + 1.5FH for the stem cells and with TS medium without supplements for the differentiated cells. On the day of interest, cells were resolved in 7 mL TRIzol solution (Invitrogen), and total RNA was prepared according to the manufacturer's instruction.

Northern Hybridization.

For Northern hybridization analysis, cDNA of Cdx2, Fgfr2, Esrrb, Ascl2, Gcm1, Tpbpa, Pl-1, Pou5f1, and Gapdh was used as the templates to generate digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled cRNA probes, using the Strip-EZ RNA labeling kit (Ambion) with DIG-labeled UTP (Roche Diagnostics) as the substrate. Northern hybridization was performed as described previously (38).

Chimera Formation with WT Embryos.

GFPntTS cells were cultured for 2 days in 80CM + 1.5FH and introduced into the blastocoel of blastocysts (3.5 dpc) with ICR background, using a piezo-actuated microinjection method (39). Injected blastocysts were transferred into the uteri of 2.5-dpc pseudopregnant ICR female mice and recovered at 10.5 and 18.5 dpc. All images were captured with a DP70 Olympus digital camera, using Olympus Analysis software to apply color to EGFP (green).

DNA Microarray Analysis.

Eleven total RNA samples from ntTS, TS, and ES cell lines were used to make biotin-labeled cRNA, using 1-cycle target labeling and control reagents, and the cRNA was hybridized with the Murine Genome 430 2.0 Array (M430_2) (Affymetrix). The hybridized arrays were scanned using the GeneChip Scanner3000, and the results were calculated and compared using the GeneChip Operation System (GCOS) (Affymetrix). The gene set was extracted using the judgment of the GCOS algorithm.

MS-qPCR.

ntTS and TS cells were harvested at day 4 in 80CM + 1.5FH and the DNA was extracted, cut by PstI, and purified (P template). Four micrograms of P template was digested by 80 units of methylation-sensitive NotI and purified (PN template). P and PN templates of each cell line were adjusted to 10 ng/μL, and 1 μL of template DNA in 20 μL of real-time PCR mixture [1 × SYBR mixture (Applied Biosystems), 4.5 μM of F and R primers, 5% DMSO, and 1 M betaine] was used to measure the intact primer target loci in an ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). The primers designed for the 27 target loci are described in Table S2. The DNA methylation level at each NotI site was defined as the amount of DNA in the PN template relative to that in the P template. The amount of DNA in the reaction mix was normalized by the value obtained with the primer pair of Xist1, which was designed to amplify the fragments with no NotI site. More than 3 independent PCR experiments were performed in triplicate.

D-REAM Analysis and Data Processing.

The extracted DNA was processed to perform D-REAM, using a genomewide DNA methylation analysis method as described elsewhere (26). Briefly, 5 μg of DNA was digested with HpyCh4IV (New England BioLabs), purified, and ligated with 2 sets of adapter oligos in sequence. The ligated materials were subjected to ligation-mediated PCR, purified, labeled using the GeneChip WT Double Stranded DNA Terminal Labeling Kit (Affymetrix), and hybridized with NotSAT custom-designed microarrays (see SI Methods). The raw intensity data were mapped on the mouse genomic sequence using probe information data, and the median intensity value was calculated for each HpyCH4IV-TaqI fragment from the intensity values of the corresponding probes. The logarithmic values of median intensity were linearly normalized using the fragment length as the function and designated as the logMED value (see Fig. S3 A and B).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Chromosome Science Labo (Hokkaido, Japan) for technical support. This work was supported by the Program for Promotion of Basic Research Activities for Innovative Biosciences; by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan 20062003 (to S.T.) and 15080202 (to K.S.); and by Research Fellowships of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science for Young Scientists (to M.O.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

See Commentary on page 16014.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0908009106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Wakayama T, Rodriguez I, Perry AC, Yanagimachi R, Mombaerts P. Mice cloned from embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14984–14989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wakayama T, Perry AC, Zuccotti M, Johnson KR, Yanagimachi R. Full-term development of mice from enucleated oocytes injected with cumulus cell nuclei. Nature. 1998;394:369–374. doi: 10.1038/28615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wakayama T, Yanagimachi R. Cloning of male mice from adult tail-tip cells. Nat Genet. 1999;22:127–128. doi: 10.1038/9632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogura A, et al. Production of male cloned mice from fresh, cultured, and cryopreserved immature Sertoli cells. Biol Reprod. 2000;62:1579–1584. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod62.6.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanaka S, et al. Placentomegaly in cloned mouse concepti caused by expansion of the spongiotrophoblast layer. Biol Reprod. 2001;65:1813–1821. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod65.6.1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou Q, Jouneau A, Brochard V, Adenot P, Renard JP. Developmental potential of mouse embryos reconstructed from metaphase embryonic stem cell nuclei. Biol Reprod. 2001;65:412–409. doi: 10.1093/biolreprod/65.2.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wakisaka-Saito N, et al. Chorioallantoic placenta defects in cloned mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;349:106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill JR, et al. Clinical and pathologic features of cloned transgenic calves and fetuses (13 case studies) Theriogenology. 1999;51:1451–1465. doi: 10.1016/s0093-691x(99)00089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wells DN, Misica PM, Tervit HR. Production of cloned calves following nuclear transfer with cultured adult mural granulosa cells. Biol Reprod. 1999;60:996–1005. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod60.4.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill JR, et al. Evidence for placental abnormality as the major cause of mortality in first-trimester somatic cell cloned bovine fetuses. Biol Reprod. 2000;63:1787–1794. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.6.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Sousa PA, et al. Evaluation of gestational deficiencies in cloned sheep fetuses and placentae. Biol Reprod. 2001;65:23–30. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod65.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palmieri C, Loi P, Reynolds LP, Ptak G, Della Salda L. Placental abnormalities in ovine somatic cell clones at term: A light and electron microscopic investigation. Placenta. 2007;28:577–584. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rossant J, Cross JC. Placental development: Lessons from mouse mutants. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:538–548. doi: 10.1038/35080570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanaka S, Kunath T, Hadjantonakis AK, Nagy A, Rossant J. Promotion of trophoblast stem cell proliferation by FGF4. Science. 1998;282:2072–2075. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oda M, Shiota K, Tanaka S. Trophoblast stem cells. Methods Enzymol. 2006;419:387–400. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)19015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wakayama S, et al. Equivalency of nuclear transfer-derived embryonic stem cells to those derived from fertilized mouse blastocysts. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2023–2033. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duncan SA, et al. Expression of transcription factor HNF-4 in the extraembryonic endoderm, gut, and nephrogenic tissue of the developing mouse embryo: HNF-4 is a marker for primary endoderm in the implanting blastocyst. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7598–7602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rossant J. Stem cells from the mammalian blastocyst. Stem Cells. 2001;19:477–482. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.19-6-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dean W, et al. Conservation of methylation reprogramming in mammalian development: Aberrant reprogramming in cloned embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13734–13738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241522698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bourc'his D, et al. Delayed and incomplete reprogramming of chromosome methylation patterns in bovine cloned embryos. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1542–1546. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00480-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chung YG, Ratnam S, Chaillet JR, Latham KE. Abnormal regulation of DNA methyltransferase expression in cloned mouse embryos. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:146–153. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.014076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohgane J, et al. DNA methylation variation in cloned mice. Genesis. 2001;30:45–50. doi: 10.1002/gene.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shiota K, et al. Epigenetic marks by DNA methylation specific to stem, germ and somatic cells in mice. Genes Cells. 2002;7:961–969. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2002.00574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sakamoto H, et al. Cell type-specific methylation profiles occurring disproportionately in CpG-less regions that delineate developmental similarity. Genes Cells. 2007;12:1123–1132. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hattori N, et al. Preference of DNA methyltransferases for CpG islands in mouse embryonic stem cells. Genome Res. 2004;14:1733–1740. doi: 10.1101/gr.2431504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohgane J, Yagi S, Shiota K. Epigenetics: The DNA methylation profile of tissue-dependent and differentially methylated regions in cells. Placenta. 2008;29(Suppl A):S29–S35. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perry AC, et al. Mammalian transgenesis by intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Science. 1999;284:1180–1183. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5417.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jouneau A, et al. Developmental abnormalities of NT mouse embryos appear early after implantation. Development. 2006;133:1597–1607. doi: 10.1242/dev.02317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miki H, et al. Embryonic rather than extraembryonic tissues have more impact on the development of placental hyperplasia in cloned mice. Placenta. 2009;30:543–546. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kishigami S, et al. Successful mouse cloning of an outbred strain by trichostatin A treatment after somatic nuclear transfer. J Reprod Dev. 2007;53:165–170. doi: 10.1262/jrd.18098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagy A, et al. Embryonic stem cells alone are able to support fetal development in the mouse. Development. 1990;110:815–821. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.3.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wakayama T, Yanagimachi R. Mouse cloning with nucleus donor cells of different age and type. Mol Reprod Dev. 2001;58:376–383. doi: 10.1002/1098-2795(20010401)58:4<376::AID-MRD4>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Constant F, et al. Large offspring or large placenta syndrome? Morphometric analysis of late gestation bovine placentomes from somatic nuclear transfer pregnancies complicated by hydrallantois. Biol Reprod. 2006;75:122–130. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.051581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ohgane J, et al. The Sall3 locus is an epigenetic hotspot of aberrant DNA methylation associated with placentomegaly of cloned mice. Genes Cells. 2004;9:253–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1356-9597.2004.00720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kremenskoy M, et al. DNA methylation profiles of donor nuclei cells and tissues of cloned bovine fetuses. J Reprod Dev. 2006;52:259–266. doi: 10.1262/jrd.17098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kishigami S, et al. Normal specification of the extraembryonic lineage after somatic nuclear transfer. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:1801–1806. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Niwa H, et al. Interaction between Oct3/4 and Cdx2 determines trophectoderm differentiation. Cell. 2005;123:917–929. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iwatsuki K, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of a new member of the rat placental prolactin (PRL) family, PRL-like protein H. Endocrinology. 1998;139:4976–4983. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.12.6373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wakayama T, et al. Differentiation of embryonic stem cell lines generated from adult somatic cells by nuclear transfer. Science. 2001;292:740–743. doi: 10.1126/science.1059399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.