Abstract

Higher levels of cysteinyl cathepsin L were detected in human atherosclerotic lesions than in healthy aortas. However, a link between human coronary heart disease (CHD) and systemic cathepsin L levels remains unknown. A total of 137 volunteers with diagnosed acute and previous myocardial infarction (MI) and stable and unstable angina pectoris in addition to 48 controls were asked to undergo coronary angiography. Serum cathepsin L, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, fasting glucose, and lipid protein profiles were measured. Serum cathepsin L levels were significantly higher in patients with CHD than in those without CHD (p <0.001). The significance persisted after adjusting for most major confounders. Patients with unstable angina pectoris had higher serum cathepsin L levels than those with stable angina pectoris (p = 0.02). Of patients with acute coronary syndrome, those with acute MI had higher serum cathepsin L levels than those with unstable angina pectoris (p <0.05) and patients with previous MI had the highest levels. Importantly, serum cathepsin L associated positively with number of coronary branch luminal narrowings (R = 0.38, p <0.001), Gensini scores (R = 0.44, p <0.001), high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (R = 0.32, p <0.001), fasting glucose (R = 0.16, p <0.03), and cigarette smokers (R = 0.27, p <0.001), but inversely with high-density lipoprotein (R = -0.23, p = 0.002) and apolipoprotein A1 (R = -0.19, p = 0.01) in all subjects. In conclusion, after adjusting for these confounders, we found that serum cathepsin L correlated positively and independently with Gensini score, suggesting that serum cathepsin L serves as a novel and independent biomarker for CHD.

Cysteine protease cathepsin L has been implicated in atherogenesis.1-4 Mice deficient in cathepsin L demonstrate impaired leukocyte transmigration and attenuated atherosclerosis.5 In human atherosclerotic lesions, cathepsin L is expressed in all major vascular cell types and released into the extracellular milieu as an active enzyme for vascular tissue remodeling and its immunoreactivity is localized mainly in the fibrous caps and macrophage-rich shoulder regions, where plaque ruptures usually occur.1,6 We previously showed that serum cathepsin L levels are significantly higher in atherosclerotic patients with ≥10% stenosis of 1 main coronary artery than those without detectable lesions by coronary angiography.1 Given the proved participation of cathepsin L in mouse atherosclerosis,5,7 we hypothesized that serum cathepsin L levels would be higher in patients with coronary heart disease (CHD) than in those without this disease. Thus, serum cathepsin L may serve as a novel biomarker for vulnerable plaque and reflect the severity of coronary stenosis, hypotheses tested in 342 participants in this study to explore the relation of blood levels of cathepsin L and the severity of coronary stenosis with CHD.

Methods

From May to October 2007, a total of 342 in-hospital and clinic service volunteers >40 years of age from the Second Xiangya Hospital, Hunan, China, participated in this study, which was approved by an institutional review committee. All patients gave informed consent. Of 342 participants, 294 patients were diagnosed with CHD with clinical symptoms of chest pain, dyspnea, precordial discomfort, or left ventricular dilatation, as defined by left ventricular end-diastole dimension >50 mm and ST-T changes on electrocardiogram. All subjects were programmed for coronary angiography (Innova 3100, GE, Fairfield, Connecticut) and all patients with CHD were found to have ≥50% decrease in ≥1 main coronary artery. Angiographers calculated the sum of the Gensini score to test severity of coronary artery stenosis blindly. Previous studies have suggested an association between cysteinyl cathepsins and autoimmunity,8 cancer,9 renal failure,10 liver injury,11 parasitosis,12 and bone resorption,13 and cathepsin L expression was affected by inflammatory cytokines or growth factors.1 Therefore, patients with the following conditions were excluded from this study to limit potential confounding factors: autoimmune disease (n = 4), arthritis (n = 10), cancer (n = 4), renal failure (n = 10) and chronic hepatic diseases (n = 10), parasitosis (n = 1), tuberculosis (n = 2), hypothyroidism (n = 2), high fever (n = 6), or bacterial/viral infection (n = 20), bone fracture (n = 1), degenerative osteoarthropathy (n = 1), or use of heparin, antibiotics, hormone, aspirin, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, or statins 2 weeks before blood sampling (n = 21), which might artificially affect cathepsin L expression. Patients with accompanying rheumatic heart disease, valve heart disease, dilated cardiomyopathy, or other cardiac diseases (n = 17) were also excluded. Of the remaining 137 patients with CHD, 78 had acute coronary syndrome, including 29 with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) who were diagnosed by rapid increasing and decreasing levels of creatine kinase-MB and/or positive troponin I test with ≥1 of the following: ischemic symptoms, electrocardiographic changes indicative of ischemia, or coronary artery intervention14; 50 had unstable angina pectoris, which was diagnosed by typical chest pain at rest in the 24 hours before going to hospital, depressed ST ≥0.1 mV, and/or T-wave inversion on electrocardiogram but normal creatine kinase-MB level15; 29 had stable angina pectoris diagnosed by an invariable character of exertional chest pain 3 months before going to hospital, which meant the same degree of exertion and excitation provocation and the same location, quality, and 3- to 5-min duration, and was relieved by rest or nitroglycerin in the same minutes; and 29 had previous MI (PMI) diagnosed by a clear history of MI and an average of 4.7 ± 1.2 years (mean ± SE) since the last AMI, and pathologic Q waves on electrocardiogram. A total of 48 subjects showed no evidence of CHD, including no typical chest pain on exertion, no MI by history or electrocardiogram, negative exercise test result, and <50% luminal narrowing of the coronary arteries, and they were selected as the controls.

Patient age, gender, smoking history, alcohol consumption history, body mass index, hypertension (systolic and diastolic blood pressures), heart rate, and medication history were recorded. Smokers were defined as subjects who had smoked tobacco for ≥3 years. Peripheral blood samples were obtained before angiography or emergency percutaneous coronary intervention for patients with AMI. Subjects were fasted for 12 hours before blood collection. Serum concentrations of total cholesterol, triglyceride, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, apolipoprotein A1, apolipoprotein B, glucose, creatinine, uric acid, and creatine kinase-MB were determined using standard laboratory procedures. Serum levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) were measured with an enhanced immunoturbidimetric assay. Human serum cathepsin L levels, which were probably in their proteolytically processed forms,1,6 were determined blindly using enzyme-linked immunoassay kits as previously described.1 We detected no significant differences of serum cathepsin L levels between the blood samples from the artery and the vein or those from the plasma preparation (data not shown).

Coronary angiography was performed in multiple views according to the standard Judkins technique16 by using the number of involved coronary branches and the sum of Gensini scores to assess severity of coronary artery stenosis. Simple affection was defined as 1 coronary stenosis ≥50%; complex affection was defined as >1 coronary branch involved and ≥1 coronary stenosis ≥50%. The Gensini score system17 yields a qualitative evaluation of coronary angiogram, which grades the narrowing of the coronary artery lumen as 1 for 1% to 25% narrowing, 2 for 26% to 50% narrowing, 4 for 51% to 75% narrowing, 8 for 76% to 90% narrowing, 16 for 91% to 99% narrowing, and 32 for total occlusion. This score is then multiplied by a factor that takes into account the importance of the lesion position in the coronary arterial tree, e.g., 5 for the left main coronary artery, 2.5 for the left anterior descending branch or circumflex artery, 1.5 for the midregion, 1 for the distal left anterior descending branch, and 1 for the mid-distal region of the circumflex artery or the right coronary artery.

Clinical data and serum cathepsin L values from controls without CHD were compared with those with CHD using independent-sample t test, nonparametric Mann-Whitney test (for hs-CRP due to skewed distribution), and Fisher’s exact test. We used logistic regression analysis to find independent risk factors of CHD. Values were compared in different subgroups (including stable and unstable angina pectoris, AMI, and PMI) and controls using one-way analysis of variance least significant difference test, nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test (for hs-CRP and fasting glucose because of skewed distribution), and Pearson chi-square test. One-way analysis of variance was also used to compare cathepsin L levels in control, simple affection, and complex affection groups. To analyze the correlations of cathepsin L and other values, we used Pearson correlation test (for age, blood pressure, uric acid, creatinine, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, apolipoprotein A1, and apolipoprotein B) and nonparametric Spearman correlation test (for triglyceride, hs-CRP, glucose, creatine kinase, and Gensini scores due to skewed distribution, for smokers and number of stenotic coronary branches because of ranked data). To avoid the influence of potential confounders when analyzing cathepsin L data, we adjusted for age, smoker status, creatinine, uric acid, creatine kinase, HDL cholesterol, apolipoprotein A1, glucose, or hs-CRP using a multiple linear stepwise regression model. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

In this study, we discovered that human serum cathepsin L levels were significantly higher in patients with CHD than in those without CHD (p <0.001), as were age, creatinine, creatine kinase-MB, uric acid, fasting glucose, and hs-CRP levels (Table 1). In contrast, HDL cholesterol (p <0.001) and its main component apolipoprotein A1 (p = 0.01) were decreased in patients with CHD. Fisher’s exact test indicated that the selection of patients with a history of smoking and alcohol consumption, gender differences, and diabetic mellitus status, important risk factors of CHD, showed no significant differences between CHD and non-CHD groups (Table 1). Using Pearson and nonparametric Spearman correlation tests for all collected variables, we demonstrated that human serum cathepsin L levels were not associated with age, alcohol consumption, apolipoprotein B, diabetes, hemoglobin, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, gender, total cholesterol, or triglyceride, but associated strongly with apolipoprotein A1, creatine kinase-MB, creatinine, fasting glucose, HDL cholesterol, hs-CRP, smoker status, and uric acid (Table 2). After adjustment for these cathepsin L-associated variables listed in Table 2 and age, due to its significant association with CHD (Table 1), as possible confounders in a multiple linear regression model, we found that smoker status (B = 0.18), uric acid (B = 0.18), and hs-CRP (B = 0.14) were correlated independently with serum cathepsin L. Like creatinine, hs-CRP, fasting glucose, and HDL cholesterol, cathepsin L was an independent risk factor of CHD (p <0.001, after adjusting for all cathepsin L-associated variables listed in Table 2 except creatine kinase-MB, which is not a CHD risk factor, and 3 common CHD risk factors, i.e., age, hypertension, and lowdensity lipoprotein cholesterol, multivariate binary logistic regression test; Table 3). Cathepsin L levels remained significantly higher in patients with CHD than in controls after adjusting for all these variables (p <0.001). Therefore, an increase of serum cathepsin L levels by 1 ng/ml may increase the risk of CHD by 2.34-fold (exp[B]; Table 3).

Table 1.

Clinical data and serum cathepsin L comparison in patients with and without coronary heart disease

| Variable | No CHD (n = 48) | CHD (n = 137) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 59.2 ± 1.0 | 62.7 ± 0.8 | 0.006* |

| Apolipoprotein A1 (μmol/L) | 1.2 ± 0.0 | 1.1 ± 0.0 | 0.01* |

| Apolipoprotein B (μmol/L) | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 0.59* |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 77.8 ± 1.7 | 79.2 ± 1.0 | 0.46* |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 128.7 ± 2.9 | 131.5 ± 1.9 | 0.43* |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 22.8 ± 0.6 | 23.6 ± 0.2 | 0.22* |

| Cathepsin L (ng/ml) | 3.9 ± 0.2 | 5.6 ± 0.1 | <0.001* |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 69.3 ± 3.2 | 82.5 ± 1.9 | <0.001* |

| Creatine kinase-MB (U/L) | 13.0 ± 0.8 | 28.8 ± 5.4 | 0.005* |

| hs-CRP (mg/L) | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 10.3 ± 1.7 | <0.001† |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 5.4 ± 0.1 | 5.9 ± 0.1 | 0.001* |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 127.3 ± 2.1 | 126.2 ± 1.4 | 0.67* |

| HDL cholesterol (μmol/L) | 1.3 ± 0.0 | 1.1 ± 0.0 | <0.001* |

| Low-density lipoprotein | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 0.13* |

| cholesterol (μmol/L) | |||

| Total cholesterol (μmol/L) | 4.4 ± 0.1 | 4.4 ± 0.1 | 0.84* |

| Triglyceride (μmol/L) | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 0.15* |

| Uric acid (μmol/L) | 321.0 ± 13.4 | 356.3 ± 7.4 | 0.02* |

| Alcohol nondrinkers/drinkers | 38/10 | 108/29 | 1.00‡ |

| Nondiabetics/diabetics | 42/6 | 114/23 | 0.65‡ |

| Women/men | 13/35 | 29/108 | 0.43‡ |

| Nonsmokers/smokers | 29/19 | 68/69 | 0.24‡ |

Values are means ± SEs or numbers of subjects.

Independent-samples t test.

Nonparametric Mann-Whitney test.

Fisher’s exact test.

Table 2.

Variables associated with cathepsin L in all subjects (n = 185)

| Variable | Correlation Coefficient | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Apolipoprotein A1 (μmol/L) | -0.19 | 0.01* |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 0.24 | 0.001* |

| Creatine kinase-MB (U/L) | 0.25 | 0.001† |

| hs-CRP (mg/L) | 0.32 | <0.001† |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 0.16 | 0.03† |

| HDL cholesterol (μmol/L) | -0.23 | 0.002* |

| Smoker | 0.27 | <0.001† |

| Uric acid (μmol/L) | 0.26 | <0.001* |

Pearson correlation test.

Nonparametric Spearman correlation test.

Table 3.

Independent risk factors of coronary heart disease*

| Variable | B | Exp (B) (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cathepsin L (ng/ml) | 0.85 | 2.34 (1.57-3.50) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 0.03 | 1.03 (1.00-1.06) | 0.04 |

| hs-CRP (mg/L) | 0.28 | 1.32 (1.07-1.64) | 0.01 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 0.64 | 1.89 (1.05-3.39) | 0.03 |

| HDL cholesterol (μmol/L) | -3.41 | 0.03 (0.00-0.44) | 0.01 |

Binary logistic regression (chi-square = 88.50, p <0.001, constant -8.62). Dependent variable is CHD; induced variables are age, apolipoprotein A1, cathepsin L, creatinine, hs-CRP, fasting glucose, HDL cholesterol, hypertension, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, smoker status, and uric acid.

CI = confidence interval.

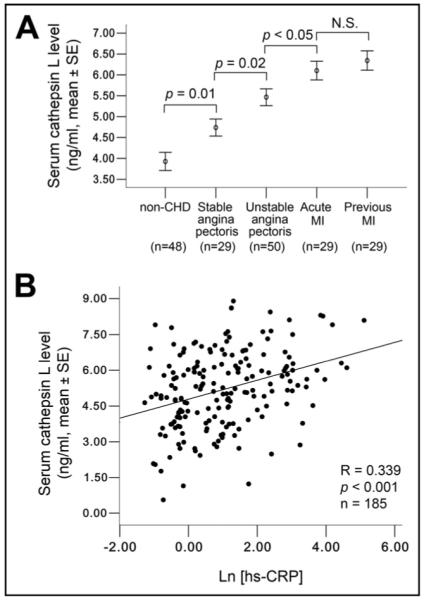

To evaluate the changes of serum cathepsin L levels in different types of CHD, we grouped the 137 patients with CHD into 4 subgroups: stable angina pectoris (n = 29), unstable angina pectoris (n = 50), AMI (n = 29), and PMI (n = 29). In one-way analysis of variance, patients with unstable angina pectoris had higher serum cathepsin L levels than patients with stable angina pectoris (p = 0.02). In these patients with acute coronary syndrome, the difference in cathepsin L levels reached statistical significance between subjects with AMI and those with unstable angina pectoris (p = 0.04). Interestingly, patients with stabilized MI did not show decreased serum cathepsin L. Instead, we detected higher cathepsin L levels from patients with PMI than from those with AMI, although the difference was not significant (p = 0.50; Figure 1). After grouping patients as having MI (AMI and PMI together, n = 58) and not having MI (including all with angina pectoris and no CHD, n = 127), we found that serum cathepsin L levels in the MI group were significantly higher than those in the non-MI group (6.2 ± 0.2 vs 4.7 ± 0.1 ng/ml, p <0.001). Among all tested risk factors, cathepsin L (p <0.001), systolic blood pressure (p = 0.003), creatinine (p = 0.001, Pearson correlation analysis), hs-CRP (p <0.001), HDL cholesterol (p <0.03), and smoker status (p <0.02, Spearman correlation analysis) were the only factors that showed significant difference between the 2 groups. However, after adjusting for these confounders in a logistic regression analysis, cathepsin L (p <0.001, exp[B] = 1.95), hs-CRP (p <0.001, exp[B] = 1.13) and systolic blood pressure (p = 0.004, exp[B] = 0.97) became the only independent variables of MI.

Figure 1.

Serum cathepsin L levels in subgrouped patients and correlation with hs-CRP. (A) One-way analysis of variance least significant difference test established significant differences in patients without CHD, with stable angina pectoris, with unstable angina pectoris, with AMI, and with PMI (3.9 ± 0.2, 4.7 ± 0.2, 5.5 ± 0.2, 6.1 ± 0.2, 6.3 ± 0.2 ng/ml, mean ± SE). (B) Pearson correlation analysis showed a positive correlation between cathepsin L and hs-CRP (Ln[hs-CRP]). All p values <0.05 are considered significant.

CRP is an independent biomarker of CHD or coronary events, and its levels are increased markedly in patients with acute coronary syndrome.18 Consistent with previous studies, we found that hs-CRP levels in patients with CHD were significantly higher than those in the control group (p <0.001). It is well accepted that cathepsins are released mainly from inflammatory cells or vascular cells under inflammatory conditions.1,19 Therefore, it is conceivable that patients with higher hs-CRP levels have higher serum cathepsin L levels. By performing Pearson correlation analysis, we discovered a strong positive correlation of cathepsin L with hs-CRP in all subjects (R = 0.34, p <0.001, Figure 1). Similar positive associations were also seen in patients with CHD (R = 0.20, p <0.02), especially in those with acute coronary syndrome (R = 0.25, p <0.03), but there was no correlation between cathepsin L and hs-CRP levels in subjects without CHD (R = 0.08, p = 0.59).

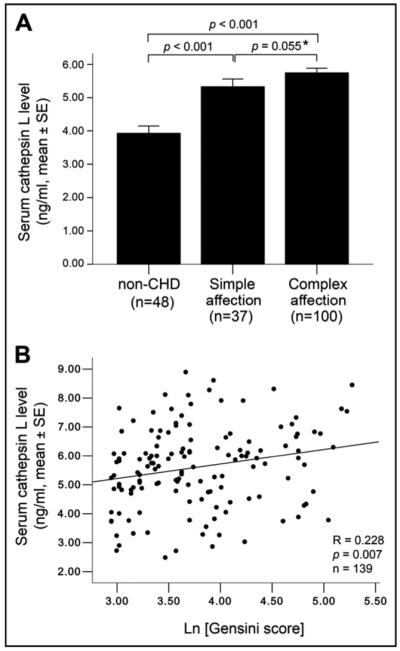

Serum cathepsin L levels were significantly higher in patients with simple coronary artery stenosis at levels of ≥50% (n = 37, p <0.001) and in patients with complex affection (n = 100, p <0.001) when these patients were compared with subjects without CHD (n = 48). Cathepsin L levels also appeared higher in patients with complex affection than in patients with simple affection (5.7 ± 0.1 vs 5.3 ± 0.2 ng/ml, p = 0.06, independent-sample t test after log-transformation; Figure 2). Nonparametric Spearman correlation test demonstrated that the number of stenotic coronary branches correlated positively with serum cathepsin L levels (R = 0.38, p <0.001). Consistently, Gensini scores, which are a frequently used index to reflect coronary stenotic severity in the clinic,20 also demonstrated a strong linear correlation with serum cathepsin L levels (R = 0.44, p <0.001). This linear correlation persisted after excluding the healthy controls (n = 46, defined as a Gensini score 0, p = 0.007; Figure 2). The Gensini scores also showed positive correlations with hs-CRP, uric acid, creatinine, creatine kinase, and fasting glucose levels and negative correlations with HDL cholesterol and apolipoprotein A1 levels (Table 4). Importantly, after adjusting for these major CHD confounders, only cathepsin L (B = 0.30, p <0.001) and HDL cholesterol (B = -0.14, p <0.05) became independent predictors of Gensini scores (multiple linear stepwise regression analysis), consistent with the hypothesis from the binary logistic regression analysis (Table 3) that serum cathepsin L level is an independent biomarker for stenotic coronary complications.

Figure 2.

Association of serum cathepsin L levels with coronary stenosis. (A) Comparison of serum cathepsin L levels among patients without CHD (defined as no coronary artery reaching 50% luminal narrowing), those with CHD with simple affection, and those with CHD with complex affection. One-way analysis of variance revealed significant differences of cathepsin L levels in subjects without CHD, with simple affection, and with complex affections. * Independent-sample t test after log-transformation. (B) Correlation of serum cathepsin L levels with Gensini scores in subjects with detectable coronary stenosis (n = 139, Gensini scores >0). Spearman correlation analysis showed a positive correlation between serum cathepsin L levels and Gensini scores (Ln[Gensini]). All p values <0.05 are considered significant.

Table 4.

Variables associated with Gensini scores in all subjects (n = 185)*

| Variable | Correlation Coefficient | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Apolipoprotein A1 (μmol/L) | -0.21 | 0.004 |

| Cathepsin L (ng/ml) | 0.44 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 0.30 | <0.001 |

| Creatine kinase-MB (U/L) | 0.39 | <0.001 |

| hs-CRP (mg/L) | 0.42 | <0.001 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 0.20 | 0.007 |

| HDL cholesterol (μmol/L) | -0.28 | <0.001 |

| Uric acid (μmol/L) | 0.23 | 0.002 |

Nonparametric Spearman correlation test.

Discussion

In this study, we found that patients with CHD had significantly higher serum cathepsin L levels than controls before and after adjusting for major CHD confounders. Significantly higher serum cathepsin L levels in patients with coronary complex or simple affections than those in patients without CHD and the positive correlation of cathepsin L with Gensini score before and after adjusting for major CHD risk factors suggest that serum cathepsin L reflects the severity of coronary atherosclerotic stenosis and serves as an independent predictor of human CHD.

Increased serum cathepsin L in patients with obvious coronary stenosis is consistent with the concept that coronary stenosis is a proteolytic process involving proteases such as cathepsin L, which is shear-sensitive and upregulated during vascular remodeling.21 Due to the coronary artery anatomic characteristics of the multiple branches, narrowings, and inflections, oscillatory flows during cardiac systole and diastole changes, and collateral circulation counterflow during coronary artery obstruction, it is plausible that the vascular wall may secrete cathepsin L into the circulation under the influence of inflammation and result in higher serum cathepsin L. Our previous studies suggested that inflammatory cells, vascular endothelium, and smooth muscles are important sources of human cathepsin L.1 However, other cell types including cardiomyocytes and myofibroblasts may also contribute to increased serum cathepsin L in patients with CHD. Although reports from rat hypertensive heart failure22 and mouse MI (Shi, unpublished data) models showed mild induction of cathepsin L expression, increased inflammation, extensive cardiomyocyte death, and myofibroblast proliferation during cardiac remodeling may increase cathepsin L secretion from these cell types. From our analysis with the CHD subgroup of patients, it is clear that cathepsin L levels were much higher in those with acute coronary syndrome than in those with stable angina pectoris and without CHD, suggesting that cathepsin L is a hallmark of unstable atherosclerotic plaque and myocardial ischemic injury. Indeed, we detected higher cathepsin L levels in patients with AMI than in those with unstable angina pectoris, likely due to active matrix degeneration, plaque destabilization, and consequent thrombosis during pathogenesis of AMI. Moreover, serum cathepsin L levels correlated positively with hs-CRP in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Atherosclerotic plaque instability and rupture induced by inflammation are the major mechanisms of acute coronary syndrome or an acute clinical event. CRP, an inflammation biomarker, is associated with progression of atherosclerosis. CRP expression is increased in unstable coronary plaques and decreased in calcified stable plaques.23 Multiple prospective epidemiologic studies have shown that an increase of hs-CRP predicts MI incidence and ischemia recurrence in those with unstable angina, undergoing percutaneous angioplasty, and presenting to emergency rooms with acute coronary syndrome.24 Thus, the significant positive correlation between cathepsin L and hs-CRP supports the hypothesis that cathepsin L production by activated cells and its release into the extracellular milieu and the circulation link strongly to local inflammatory processes within the arterial wall. This hypothesis is consistent with the observations of increased cathepsin L and hs-CRP levels in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Therefore, evaluation of combined cathepsin L and hs-CRP concentrations may assist in predicting coronary atherosclerotic lesions in the clinic.

Although not statistically significant, cathepsin L levels were higher in patients with PMI than in those with AMI, suggesting a sustained increase of serum cathepsin L after AMI. This observation is similar to what we described for cathepsin S in our previous human study (AMI 0.45 nmol/L, PMI 0.47 nmol/L).25 The 2 studies suggest that cysteinyl cathepsins participate in cardiac ventricular remodeling, a hypothesis supported by the critical role of cathepsin L in cardiac anatomy.26,27 Mice deficient in cathepsin L showed significant ventricular and atrial enlargement and then developed late onset of cardiomyopathy characterized by cardiac chamber dilation, fibrosis, and impaired cardiac contraction.27 It is possible that the myocardium benefits from activation of cathepsin L to prevent ventricular remodeling, but increased cathepsin L expression still cannot compensate for ventricular remodeling development after MI. High levels of cathepsin L in PMI could also be explained by its potential participation in postinfarction neovascularization, because cathepsin L has a critical role in the integration of circulating endothelial progenitor cells into ischemic tissue and is required for endothelial progenitor cell-mediated neovascularization, and the cathepsin L-deficient mice showed impaired functional recovery after hind-limb ischemia.3 This hypothesis is supported by the observation that cathepsin L levels in patients with MI remained significantly higher than in patients without MI after adjusting for all tested risk factors. Therefore, cathepsin L may be a sensitive indicator of MI and remodeling.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by Grant 03SSY3080 from the Department of Science and Technology of Hunan, Hunan, China (to Dr. Li); Grant 0840118N from the American Heart Association, Dallas, Texas (to Dr. Shi); and Grants HL60942, HL67283, and HL81090 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland (to Dr. Shi).

References

- 1.Liu J, Sukhova GK, Yang JT, Sun J, Ma L, Ren A, Xu WH, Fu H, Dolganov GM, Hu C, Libby P, Shi GP. Cathepsin L expression and regulation in human abdominal aortic aneurysm, atherosclerosis, and vascular cells. Atherosclerosis. 2006;184:302–311. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li W, Yuan XM. Increased expression and translocation of lysosomal cathepsins contribute to macrophage apoptosis in atherogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1030:427–433. doi: 10.1196/annals.1329.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Urbich C, Heeschen C, Aicher A, Sasaki K, Bruhl T, Farhadi MR, Vajkoczy P, Hofmann WK, Peters C, Pennacchio LA, et al. Cathepsin L is required for endothelial progenitor cell-induced neovascularization. Nat Med. 2005;11:206–213. doi: 10.1038/nm1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakagawa T, Roth W, Wong P, Nelson A, Farr A, Deussing J, Villadangos JA, Ploegh H, Peters C, Rudensky AY. Cathepsin L: critical role in Ii degradation and CD4 T cell selection in the thymus. Science. 1998;280:394–395. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5362.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitamoto S, Sukhova GK, Sun J, Yang M, Libby P, Love V, Duramad P, Sun C, Zhang Y, Yang X, Peters C, Shi GP. Cathepsin L deficiency reduces diet-induced atherosclerosis in low-density lipoprotein receptor-knockout mice. Circulation. 2007;115:2065–2075. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.688523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sukhova GK, Shi GP, Simon DI, Chapman HA, Libby P. Expression of the elastolytic cathepsins S and K in human atheroma and regulation of their production in smooth muscle cells. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:576–583. doi: 10.1172/JCI181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapman HA, Riese RJ, Shi GP. Emerging roles for cysteine proteases in human biology. Annu Rev Physiol. 1997;59:63–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Villadangos JA, Bryant RA, Deussing J, Driessen C, Lennon-Duménil AM, Riese RJ, Roth W, Saftig P, Shi GP, Chapman HA, Peters C, Ploegh HL. Proteases involved in MHC class II antigen presentation. Immunol Rev. 1999;172:109–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joyce JA, Baruch A, Chehade K, Meyer-Morse N, Giraudo E, Tsai FY, Greenbaum DC, Hager JH, Bogyo M, Hanahan D. Cathepsin cysteine proteases are effectors of invasive growth and angiogenesis during multistage tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:443–453. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vonend O, Apel T, Amann K, Sellin L, Stegbauer J, Ritz E, Rump LC. Modulation of gene expression by moxonidine in rats with chronic renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:2217–2222. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding WX, Yin XM. Dissection of the multiple mechanisms of TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis in liver injury. J Cell Mol Med. 2004;8:445–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2004.tb00469.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sriveny D, Raina OK, Yadav SC, Chandra D, Jayraw AK, Singh M, Velusamy R, Singh BP. Cathepsin L cysteine proteinase in the diagnosis of bovine Fasciola gigantica infection. Vet Parasitol. 2006;135:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Everts V, Korper W, Hoeben KA, Jansen ID, Bromme D, Cleutjens KB, Heeneman S, Peters C, Reinheckel T, Saftig P, Beertsen W. Osteoclastic bone degradation and the role of different cysteine proteinases and matrix metalloproteinases: differences between calvaria and long bone. Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1399–1408. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, Bassand JP. Myocardial infarction redefined—a consensus document of the Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:959–969. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00804-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braunward E. Unstable angina: a classification. Circulation. 1989;80:410–414. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.2.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Judkins MP. Percutaneous transfemoral selective coronary arteriography. Radiol Clin North Am. 1968;6:467–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gensini GG. A more meaningful scoring system for determining the severity of coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 1983;51:606. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(83)80105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Auer J, Berent R, Lassnig E, Eber B. C-reactive protein and coronary artery disease. Jpn Heart J. 2002;43:607–619. doi: 10.1536/jhj.43.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu J, Sukhova GK, Sun JS, Xu WH, Libby P, Shi GP. Lysosomal cysteine proteases in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1359–1366. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000134530.27208.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adams MR, Nakagomi A, Keech A, Robinson J, McCredie R, Bailey BP, Freedman SB, Celermajer DS. Carotid intima-media thickness is only weakly correlated with the extent and severity of coronary artery disease. Circulation. 1995;92:2127–2134. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.8.2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Platt MO, Ankeny RF, Jo H. Laminar shear stress inhibits cathepsin L activity in endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1784–1790. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000227470.72109.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng XW, Murohara T, Kuzuya M, Izawa H, Sasaki T, Obata K, Nagata K, Nishizawa T, Kobayashi M, Yamada T, et al. Superoxide-dependent cathepsin activation is associated with hypertensive myocardial remodeling and represents a target for angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker treatment. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:358–369. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.071126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Norja S, Nuutila L, Karhunen PJ, Goebeler S. C-reactive protein in vulnerable coronary plaques. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:545–548. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.038729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geluk CA, Post WJ, Hillege HL, Tio RA, Tijssen JG, van Dijk RB, Dijk WA, Bakker SJ, de Jong PE, van Gilst WH, Zijlstra F. C-reactive protein and angiographic characteristics of stable and unstable coronary artery disease: data from the prospective PREVEND cohort. Atherosclerosis. 2008;196:372–382. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu J, Ma L, Yang J, Ren A, Sun Z, Yan G, Sun J, Fu H, Xu W, Hu C, Shi GP. Increased serum cathepsin S in patients with atherosclerosis and diabetes. Atherosclerosis. 2006;186:411–419. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petermann I, Mayer C, Stypmann J, Biniossek ML, Tobin DJ, Engelen MA, Dandekar T, Grune T, Schild L, Peters C, Reinheckel T. Lysosomal, cytoskeletal, and metabolic alterations in cardiomyopathy of cathepsin L knockout mice. FASEB J. 2006;20:1266–1268. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5517fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stypmann J, Gläser K, Roth W, Tobin DJ, Petermann I, Matthias R, Mönnig G, Haverkamp W, Breithardt G, Schmahl W, Peters C, Reinheckel T. Dilated cardiomyopathy in mice deficient for the lysosomal cysteine peptidase cathepsin L. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6234–6239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092637699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]