Abstract

Kaposi sarcoma herpes virus (KSHV), also known as human herpesvirus-8, plays an important role in the pathogenesis of Kaposi sarcoma (KS), multicentric Castleman disease (MCD) of the plasma cell type, and primary effusion lymphoma. KSHV is rarely associated with the hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS), but when it does occur, it most occurs in immunocompromised patients. We report herein an unusual case of KSHV-associated HPS in an immunocompetent patient. A previously healthy 62-yr-old male was referred for evaluation of leukocytopenia and multiple lymphadenopathies. After a lymph node biopsy, he was diagnosed with MCD of the plasma cell type. KSHV DNA was detected in the lymph node tissue by polymerase chain reaction. Following a short-term response of the leukocytopenia to prednisolone, mental change, left side weakness, fever, thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia, and renal failure developed. Despite intravenous immunoglobulin therapy and plasmapheresis, he expired. The lymph nodes were infiltrated by hemophagocytic histiocytes in the sinuses. Pulmonary nodules and gastric erosions were shown to be KS. KSHV DNA was detected in the stomach, lung, and liver. This is the first case of multiple KSHV associated diseases including MCD and KS with KSHV-associated hemophagocytic syndrome in an HIV-negative, non-transplant, immunocompetent patient.

Keywords: Herpesvirus 8, Human; Lymphohistiocytosis, Hemophagocytic; Giant Lymph Node Hyperplasia; Sarcoma, Kaposi

INTRODUCTION

Kaposi sarcoma herpes virus (KSHV), also known as human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8), is a gamma 2 herpesvirus or rhadinovirus. The target cells of KSHV are relatively broad, and include B and T lymphocytes, endothelial cells, and subsets of monocytes and macrophages (1). It is well-known that KSHV is associated with Kaposi sarcoma (KS), multicentric Castleman disease (MCD; pathologically, the plasma cell variant), and primary effusion lymphoma (1). KSHV has been detected in 40-50% of HIV-negative patients with MCD, and in nearly all HIV-positive patients with MCD (2). KSHV-positive Castleman disease has its unique histopathologic features owing to the accumulation of virus-infected lymphocytes in the mantle zone, which result in progressive follicular lysis and up-regulation of low affinity nerve growth factor receptor in the stroma around the regressed lymphoid follicles (3). According to recent reports, KSHV is rarely related to the hemophagocytic syndrome, mostly in immunocompromised hosts, such as HIV-positive or transplantation patients (4, 5). However, KSHV-associated hemophagocytic syndrome has also been described in a HIV-negative, immunocompetent patient with the plasmablastic variant of MCD (plasmablastic microlymphoma) (6). Herein, we provide another example of KSHV-associated hemophagocytic syndrome concomitant with KS and Castleman disease of the plasma cell type in a HIV-negative, immunocompetent patient.

CASE REPORT

Clinical history

A 62-yr-old male patient was referred to the Department of Oncology due to a leukocytopenia, anemia and splenomegaly, which was discovered during the evaluation of three-vessel heart disease. He had hypertension, chronic alcoholism, was an ex-smoker, and had diabetes mellitus, which had been detected three months previously. There was no history suggesting immune deficiency. The HIV ELISA test was negative. Laboratory data revealed leukocytopenia and anemia (WBC, 1.98×103/µL; Hb, 9.8 g/dL; and platelets, 166×103/µL). The blood glucose level was normal (101 mg/dL). An abdominal and chest computerized tomography revealed splenomegaly and multiple lymphadenopathies in the mediastinum, axilla, abdomen, and pelvic cavity. After excisional biopsy of a left submental lymph node, he was diagnosed with Castleman disease of the plasma cell type. A bone marrow biopsy was interpreted as a T cell lymphoproliferative disorder. He was discharged after prednisolone treatment. However, he returned to the emergency room nine days later because of altered mental status, fever, and left side weakness. The laboratory data obtained in the emergency department was significant for severe thrombocytopenia (WBC, 5.50×103/µL; Hb, 9.8 g/dL; and platelets, 21×103/µL) and an elevated blood urea nitrogen level (36 mg/dL). Brain magnetic resonance image revealed a multifocal acute ischemic infarction in the right cerebral hemisphere. A peripheral blood smear displayed a few atypical plasmacytoid lymphocytes. A disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin type (ADAMTS) 13 and von Willebrand factor (VWF) cleaving protease (cp) were within normal limits (46.93%). The IL-6 level was not evaluated. There was no evidence of infection based on urine culture and respiratory examination. Although schistocytes were not detected in the peripheral blood smear findings, the sudden neurological deficits, severe thrombocytopenia with immune hemolytic anemia, fever, and renal failure together were suggestive of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), therefore, plasmapheresis and intravenous immunoglobulin treatment were initiated. However, thrombocytopenia was aggravated (platelet, 10×103/µL) and the urine output decreased to 600 cc with elevation of the BUN/Cr level to 165/2.4 mg/dL. The D-dimer was 3.60 µg/mL and the fibrin degradation products were positive (1:20). Total and direct bilirubin levels were 28.6 mg/dL and 20.0 mg/dL, respectively. He expired with acute renal failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and pulmonary edema.

Pathologic diagnosis and autopsy findings

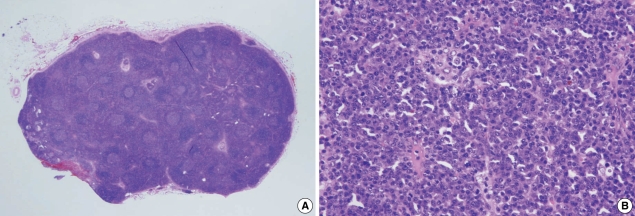

Excisional biopsy of a submentaI lymph node revealed mixed hyperplastic and atrophic lymphoid follicles with a concentric layering of lymphocytes in the mantle zone (Fig. 1A). Numerous plasma cells were aggregated in sheets in the interfollicular area with scattered large CD30 (Ki-1) positive immunoblastic cells (Fig. 1B). KSHV DNA was detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis and Epstein-Barr virus in situ hybridization was negative. The pathologic diagnosis was Castleman disease, plasma cell type.

Fig. 1.

Histologic features of initial lymph node biopsy specimen. (A) At low magnification, lymphoid follicular hyperplasia was observed with preserved nodal architecture (H&E, ×12.5). (B) Plasma cells were markedly increased in the interfollicular area (H&E, ×200).

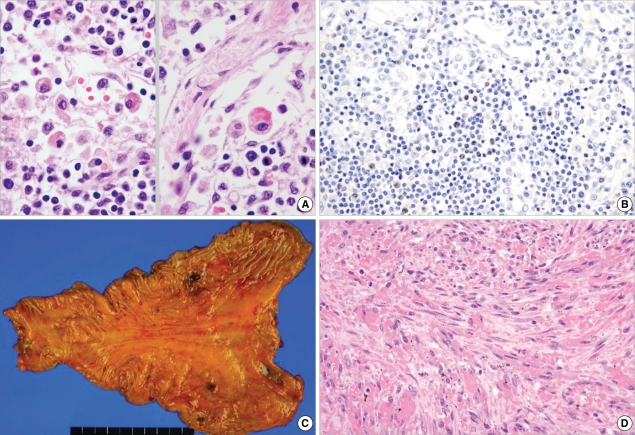

An autopsy was performed eight hours postmortem. The skin and sclera were bright yellow in color. There were multiple enlarged lymph nodes (up to 1.3 cm in diameter) in the neck, mediastinum, abdominal cavity, axilla, and inguinal area. Microscopically, the nodal architecture was diffusely effaced with paracortical hyperplasia with burnt-out lymphoid follicles. Plasma cells and plasmacytoid cells were increased in the paracortical area. In addition, many hemophagocytic histiocytes diffusely infiltrated the sinus (Fig. 2A). Some of the immunoblastic cells, putative B cells, were positive for KSHV (HHV-8) latent nuclear antigen 1 (LANA-1; Fig. 2B) based on immunohistochemistry and KSHV DNA was detected in PCR analysis. These findings strongly suggested KSHV-associated hemophagocytic syndrome.

Fig. 2.

Pathologic features of the lymph nodes and stomach at autopsy. (A) In lymph node sinuses, many macrophages engulfing red blood cells (hemophagocytic histiocytes) were observed (H&E, ×1,000). (B) A few LANA-1-positive lymphocytes were identified (LANA-1 immunostain, ×400). (C) Within the gastric mucosa, a few erosions were found in the body. (D) Microscopically, the lesion was composed of spindle-shaped endothelial cells with nuclear atypism and mitoses. Many extravasated RBCs were also observed (H&E, ×400).

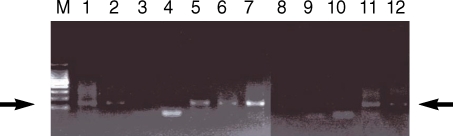

Small erosions and nodules <1 cm were found in the gastric mucosa (Fig. 2C), in the lung parenchyma, and in the pericolic fat tissue. They were composed of intersecting spindle cells with extravasated RBCs and a few mitotic figures (3/10HPF; Fig. 2D). The spindle cells immuno-stained for CD31, factor VIII, vimentin, and KSHV (HHV-8) LANA-1, and KSHV DNA was detected by PCR (Fig. 3). Therefore, the lesions were diagnosed as Kaposi sarcoma. The spleen was enlarged (810 g) with multifocal infarctions. Microscopically, the plasma cells were markedly increased in the red and white pulp with some hemosiderin-laden macrophages. The liver was mildly enlarged (2,320 g), and showed features of non-specific hypoxic damage, including periportal fibrosis and minimal portal inflammation. KSHV DNA was also detected in the liver and spleen (Fig. 3). Acute tubular necrosis was focally observed in the kidney. The heart had luminal narrowing with atherosclerosis in the anterior descending, right circumflex, and right coronary arteries. Sclerotic acellular scarring, patch fibrosis, and degeneration of myofibers suggested chronic ischemia and hypertensive heart disease. In the bone marrow from the vertebra, a few hemophagocytic histiocytes and increased plasma cells were noted.

Fig. 3.

PCR analysis for KSHV. KSHV DNA was detected in the liver (lane 5), spleen (lane 6), stomach (lane 7), lung (lane 8), and lymph nodes (lanes 11 and 12). (Lanes 1 and 2; positive control, lanes 3 and 4; negative control, lane 6; bone marrow, and lane 9; the contralateral lung).

DISCUSSION

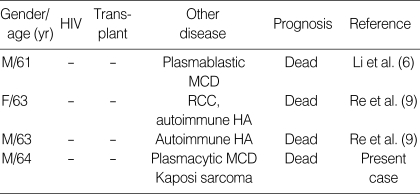

Hemophagocytic syndrome is associated with variable systemic diseases, including viral infections, as represented by the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) (7, 8). Most of the KSHV-associated hemophagocytic syndromes have been reported in immunocompromised hosts, with few reports in immunocompetent patients (6, 9). Li et al. (6), for the first time, reported a case of KSHV-associated hemophagocytic syndrome in a HIV-negative, immunocompetent host with MCD. Re et al. (9) described two additional cases in HIV-negative, non-transplant patients. Our patient had no history suggesting immune deficiency before the diagnosis of Castleman disease. Although he had diabetes mellitus, it was detected only three months previously and had been well controlled by oral hypoglycemic agents. It is improbable that the short-term administration of prednisolone for the management of Castleman disease resulted in severe immunosuppression. The major clinicopathologic features of the reported and present cases with KSHV-associated hemophagocytic syndrome in immunocompetent patients are summarized in Table 1. Notably, all four of the patients followed a rapid and fatal clinical course, and two of the patients also had MCD. All of them appeared in old age. The concurrence of KS and Castleman disease of the plasma cell type in this case further demonstrates that the hemophagocytic syndrome could occur as a fatal complication of KSHV-related disease, even in HIV-negative and non-transplant immunocompetent hosts. KSHV-associated hemophagocytic syndrome has been reported to co-occur with KSHV infection related diseases such as Kaposi sarcoma, multicentric Castleman disease or plasma effusion lymphoma in immunocompromised host. This is the first case of multiple KSHV associated diseases including MDC and KS with KSHV-associated hemophagocytic syndrome in an HIV-negative, non-transplant, immunocompetent patient. We thought that our patients died of DIC and renal failure complicated by severe hemophagocytic syndrome.

Table 1.

Summary of KSHV (HHV-8)-associated hemophagocytic syndrome in immunocompetent patients

KSHV, Kaposi sarcoma herpes virus; HHV-8, human herpesvirus-8; MCD, multicentric Castleman disease; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; HA, hemolytic anemia.

In the pathogenesis of the hemophagocytic syndrome, many cytokines, including IFN-δ, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-12, are known to be important (7). In the case of KHSV-related hemophagocytic syndrome, direct infection of monocytes by KSHV or a paracrine influence from virus reactivation in reservoir cells has been suggested as a possible pathogenetic mechanism (4). Li et al. (6) speculated that proliferation of KSHV-infected plasmablasts might have resulted in a cytokine storm, leading to virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome similar to EBV-associated T cell lymphoproliferative disorder.

IL-6 is known as a key cytokine involved in the pathogenesis of KSHV-associated diseases (7). IL-6 is a multipotent cytokine having multiple biologic activities, including promotion of B cell proliferation and differentiation with plasmacytosis, stimulation of inflammatory pathways, and induction of B cell malignancies (10). KSHV encodes a viral homologue of IL-6 (vIL-6), which can functionally mimic human IL-6 and also induce the production of human IL-6 (10). In a murine model, deregulated expression of IL-6 brought about MCD-like features, including splenomegaly, extensive plasma cell infiltration of the lymphoreticular system, and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia (11). Patients with Castleman disease of the plasma cell type have elevated serum IL-6 levels (12). vIL-6 also induces vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and induces local tissue damage and attracted inflammatory cells (13, 14). Thalidomide, a powerful anticytokine effector, has been used for resolution of the systemic manifestations of MCD (10). Recently, humanized anti-IL-6 receptor antibody (tocilizumab) has proven to be useful for the treatment of MCD (15). Although IL-6 was not evaluated in our case, the presence of abundant plasmacytoid or plasma cells in the lymph nodes and spleen, and T cell proliferation in the bone marrow, suggest that IL-6 might play an important role in disease progression and the hemophagocytic syndrome. Therefore, the present case emphasizes the consideration of anti-IL-6 therapy for the management of potentially fatal complication including hemophagocytic syndrome in MCD patients.

Footnotes

This work was partly supported by the Korean Science & Engineering Foundation (KOSEF) through the Tumor Immunity Medical Research Center at Seoul National University College of Medicine.

References

- 1.Dourmishev LA, Dourmishev AL, Palmeri D, Schwartz RA, Lukac DM. Molecular genetics of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus-8) epidemiology and pathogenesis. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2003;67:175–212. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.2.175-212.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suda T, Katano H, Delsol G, Kakiuchi C, Nakamura T, Shiota M, Sata T, Higashihara M, Mori S. HHV-8 infection status of AIDS-unrelated and AIDS-associated multicentric Castleman's disease. Pathol Int. 2001;51:671–679. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2001.01266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amin HM, Medeiros LJ, Manning JT, Jones D. Dissolution of the lymphoid follicle is a feature of the HHV8+ variant of plasma cell Castleman's disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:91–100. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200301000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fardet L, Blum L, Kerob D, Agbalika F, Galicier L, Dupuy A, Lafaurie M, Meignin V, Morel P, Lebbe C. Human herpesvirus 8-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:285–291. doi: 10.1086/375224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rimar D, Rimar Y, Keynan Y. Human herpesvirus-8: beyond Kaposi's. Isr Med Assoc J. 2006;8:489–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li CF, Ye H, Liu H, Du MQ, Chuang SS. Fatal HHV-8-associated hemophagocytic syndrome in an HIV-negative immunocompetent patient with plasmablastic variant of multicentric Castleman disease (plasmablastic microlymphoma) Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:123–127. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000172293.59785.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larroche C, Mouthon L. Pathogenesis of hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS) Autoimmun Rev. 2004;3:69–75. doi: 10.1016/S1568-9972(03)00091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eakle JF, Bressoud PF. Hemophagocytic syndrome following an Epstein-Barr virus infection: a case report and literature review. J Ky Med Assoc. 2000;98:161–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Re A, Facchetti F, Borlenghi E, Cattaneo C, Capucci MA, Ungari M, Barozzi P, Vallerini D, Potenza L, Torelli G, Rossi G, Luppi M. Fatal hemophagocytic syndrome related to active human herpesvirus-8/Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection in human immunodeficiency virus-negative, non-transplant patients without related malignancies. Eur J Haematol. 2007;78:361–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.00828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waterston A, Bower M. Fifty years of multicentric Castleman's disease. Acta Oncol. 2004;43:698–704. doi: 10.1080/02841860410002752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brandt SJ, Bodine DM, Dunbar CE, Nienhuis AW. Dysregulated interleukin 6 expression produces a syndrome resembling Castleman's disease in mice. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:592–599. doi: 10.1172/JCI114749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu SM, Waldron JA, Xie SS, Barlogie B. Expression of interleukin-6 in Castleman's disease. Hum Pathol. 1993;24:833–839. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(93)90132-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aoki Y, Jaffe ES, Chang Y, Jones K, Teruya-Feldstein J, Moore PS, Tosato G. Angiogenesis and hematopoiesis induced by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded interleukin-6. Blood. 1999;93:4034–4043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klouche M, Brockmeyer N, Knabbe C, Rose-John S. Human herpesvirus 8-derived viral IL-6 induces PTX3 expression in Kaposi's sarcoma cells. AIDS. 2002;16:F9–F18. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200205240-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuyama M, Suzuki T, Tsuboi H, Ito S, Mamura M, Goto D, Matsumoto I, Tsutsumi A, Sumida T. Anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody (tocilizumab) treatment of multicentric Castleman's disease. Intern Med. 2007;46:771–774. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.46.6262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]