Abstract

This Letter describes the synthesis and SAR of the novel positive allosteric modulator, VU0155041, a compound that has shown in vivo efficacy in rodent models of Parkinson's disease. The synthesis takes advantage of an iterative parallel synthesis approach to rapidly synthesize and evaluate a number of analogs of VU0155041.

Keywords: mGluR4, metabotropic glutamate receptor 4, allosteric modulator, PAM, Parkinson's disease

In recent years there has been great progress in the discovery and clinical development of allosteric modulators of several GPCR targets.1,2 There are several advantages of allosteric modulators over traditional orthosteric agonists/antagonists. First, specific allosteric modulators (i.e., those with no intrinsic agonist activity) only exert their effect in the presence of the endogenous ligand. Second, the potential exists for greater receptor selectivity due to sequence divergence in allosteric binding sites.1 Third, for targets such as metabotropic glutamate receptors, orthosteric ligands are most often amino acid analogs with poor brain penetration and suboptimal pharmacokinetic parameters. Our interest in allosteric modulation is centered on metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 (mGluR4), a member of the larger mGluR family of class C GPCRs. mGluR4 has been shown by a number of groups to be a potential drug target in a variety of disease states, including Parkinson's disease (PD).3-7

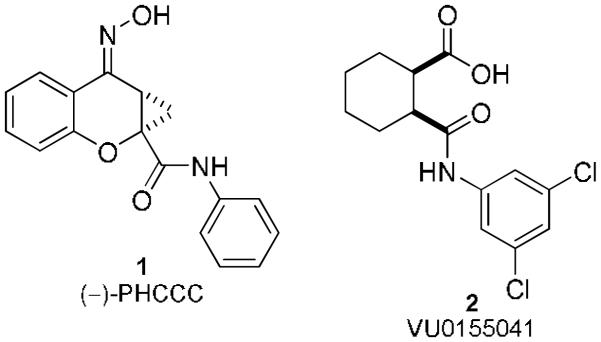

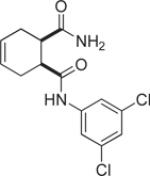

The first positive allosteric modulator (PAM) of mGluR4, (−)-PHCCC, 13,8,9, has been studied extensively by a number of groups and has shown efficacy in a number of PD rodent models.3,5 Despite these initial findings and the promise of mGluR4 activation as a treatment for PD, until 2008 very few mGluR4 PAMs had been reported in the literature.10 Recently, our laboratories have published several reports of mGluR4 PAMs; all compounds were discovered after a successful high-throughput screening (HTS) campaign initiated at Vanderbilt University.4,11-13

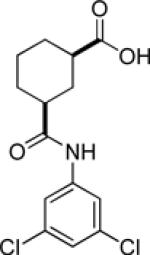

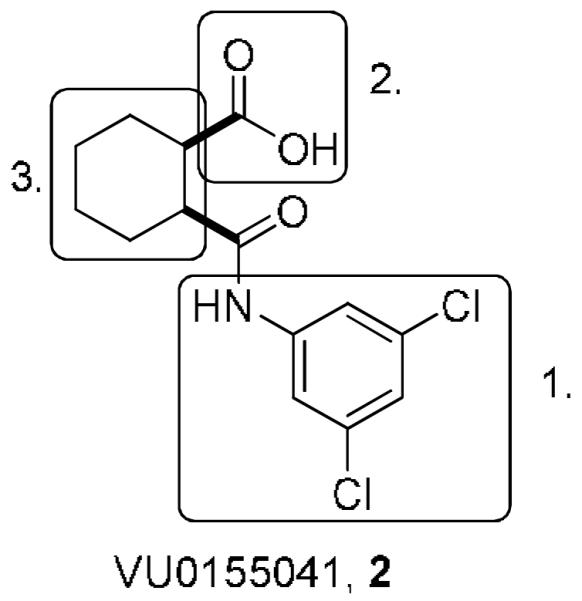

Previously, we disclosed VU0155041, 2, a novel mGluR4 positive allosteric modulator (PAM) that showed in vivo efficacy in two anti-Parkinsonian rodent models (haloperidol-induced catalepsy and reserpine-induced akinesia).4 Limited structure-activity relationship (SAR) was explored in that previous report and was restricted to the compounds found in the HTS at Vanderbilt as well as the cis/trans isomers of VU0155041 (the cis compounds were found to be significantly more active than the trans4) and the enantiomerically pure cis isomers. Herein we report a detailed SAR analysis surrounding VU015504114 as a novel mGluR4 positive allosteric modulator tool compound.4

The SAR surrounding compound 2 centered around three structural motifs: 1, exploring the 3,5-dichloroamide; 2, exploring the carboxylic acid; and 3, exploring the cyclohexyl ring (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structures of (−)-PHCCC, 1, and VU0155041, 2, two mGluR4 PAMs that show activity in vivo.

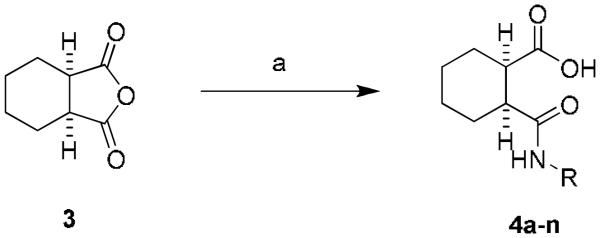

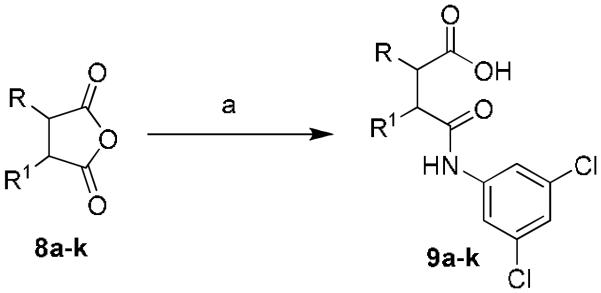

Starting from the commercially available cis-1,2-cyclohexanedicarboxylic anhydride, the carboxylic acid amide was generated after ring opening with the appropriate amine (20-84%) (Scheme 1). The 3,5-dichlorophenyl, 2, was the original hit previously reported (740 nM, GluMax = 127%).4 A number of compounds were synthesized to explore substitution around the phenyl amide 4a–n (Table 1). Similarly substituted mono- and di-substituted halogenated phenyl analogs were evaluated, and only the 3-chloro-5-fluoro, 4e, displayed any activity (2.0 μM, GluMax = 138%).15 The unsubstituted phenyl, 4h, was found to be a weak PAM (>10 μM, GluMax = 39%); whereas the benzyl analog, 4i, was inactive. Two heteroaryl compounds were also evaluated (1,3-dimethyl-1H-1,2,4-triazole, 4j, 2-pyridyl, 4k); however, these compounds were also inactive. Lastly, replacements for the phenyl group including morpholino, 4l, cyclohexyl, 4m, and cyclobutyl, 4n, were synthesized and found to be inactive. This rather ‘shallow’ SAR is a hallmark of allosteric modulators.13,16

Scheme 1.

Library synthesis of 4a–n. Reagents and conditions: (a) RR'NH, THF, 55 °C, (24-80%). All library compounds were purified by mass-directed prep LC where required.17,18

Table 1.

SAR evaluation of the amide substitution, 4a-4i.

| Compound | R | EC50 (μM) hmGluR44,a |

% Glu Max |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3,5-dichlorophenyl | 0.740 | 127 |

| 4a | 3,5-difluorophenyl | inactive | |

| 4b | 3,5-dimethylphenyl | inactive | |

| 4c | 3,5- di(trifluoromethyl)phenyl |

inactive | |

| 4d | 3,4-dimethylphenyl | inactive | |

| 4e | 3-chloro-5-fluorophenyl | 2.0 | 138 |

| 4f | 3-bromophenyl | inactive | |

| 4g | 3,4-difluorophenyl | inactive | |

| 4h | phenyl | >10 | 39 |

| 4i | benzyl | inactive | |

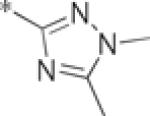

| 4j |  |

inactive | |

| 4k | 2-pyridyl | inactive | |

| 4l | morpholine | inactive | |

| 4m | Cyclohexyl | inactive | |

| 4n | Cyclobutyl | inactive |

Represents the average of at least one experiment performed in triplicate.

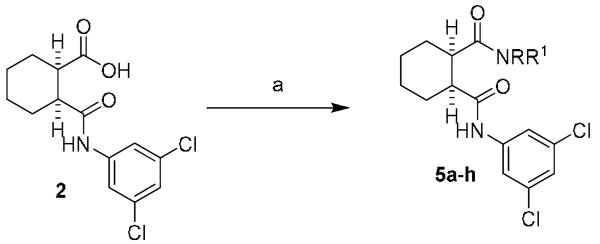

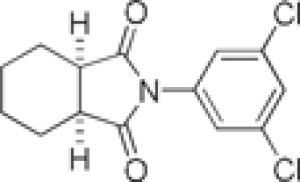

We next turned our attention to finding a suitable replacement for the carboxylic acid moiety as this group often possesses low membrane permeability across the blood-brain barrier.19-21 A variety of amide compounds were made via activation of the acid with EDC, HOBt and then coupling with the appropriate amine (Scheme 2, Table 2). The primary carboxamide, 5a, gave similar potency to the carboxylic acid 2 (950 nM vs. 740 nM). All the other secondary or tertiary amides that were evaluated were either inactive or gave a >10-fold loss in potency (5b-i). A major byproduct of the reaction, due to the proximity of the activated acid to the amide, is cyclization to form the cyclic imide, 5i, (3.3 μM, GluMax = 152%). Although this analog is more active than many of the other acid replacements; it still shows a 5-fold loss of activity versus 2, and a 3-fold loss versus 5a.

Scheme 2.

Library synthesis of 5a-i. Reagents and conditions: (a) RR'NH, EDC, HOBt, DIPEA, DMF (18-56%). EDC = 1-ethyl-3-(3′-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide, HOBt = hydroxybenzotriazole, DIPEA = diisopropyl ethylamine. All library compounds were purified by mass-directed prep LC where required.17,18

Table 2.

SAR evaluation of carboxylic acid replacements, 5a-h.

| Compound | R1 | R | EC50(μM) hmGluR44,a |

% Glu Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5a | H | H | 0.95 | 104 |

| 5b | H | Me | 10 | 106 |

| 5c | H | DiMe | Inactive | |

| 5d | H | Propyl | 9.6 | 57 |

| 5e | H | Cyclopropyl | Inactive | |

| 5f | H | Cyclopentyl | Inactive | |

| 5g | H | Cyclopropylmethyl | 10 | 80 |

| 5h | Morpholine | Inactive | ||

| 5i |  |

3.3 | 152 | |

Represents the average of at least one experiment performed in triplicate.

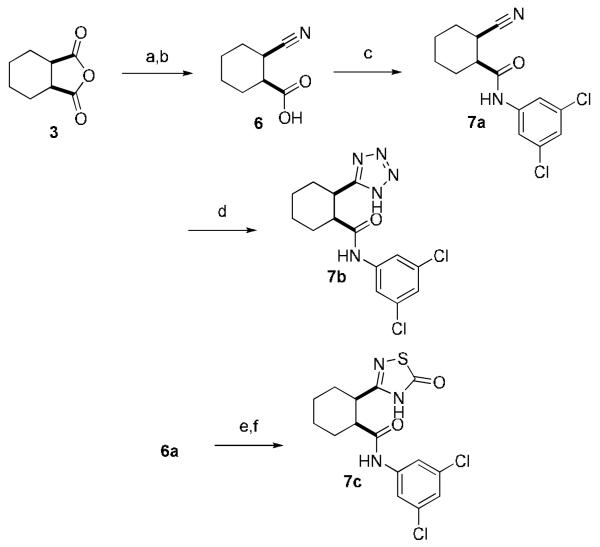

Three other acid replacements were evaluated (Table 3). The synthesis of the nitrile 7a, tetrazole 7b, and thiadiazolone 7c, is shown in Scheme 3. The nitrile compound 7a was active (2 μM, GluMax = 55%); however, the GluMax was much less than either the carboxylic acid or carboxamide. The tetrazole mimetic 7b also was active as an mGluR4 PAM (>10 μM, GluMax = 152%); however, this substitution led to a 10-fold loss in potency. The other known carboxylic acid bioisostere 7c (thiadiazolone) was inactive.20,21

Table 3.

SAR evaluation of carboxylic acid mimetics, 7a-c.

| Compound | EC50 (μM) mGluR44,a |

% Glu Max |

|---|---|---|

| 7a | 2.0 | 55 |

| 7b | >10 | 152 |

| 7c | Inactive |

Represents the average of at least one experiment performed in triplicate.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of the nitrile 7a, tetrazole 7b and thiadiazolone 7c. Reagents and conditions: (a) NH4OH, 88% (b) DIC, pyridine, carried on w/o purification (c) 3,5-dichloroaniline, EDC, HOBt, DMF, 60–73% (d) Bu3SnN3, toluene, μW, 30 min., 160 °C, 10%, (e) hydroxylamine·HCl, DMSO, DEA, (f) thiocarbonyl diimidazole, THF, rt 15% (two steps). DIC = N,N′-carbonyl diimidazole, DEA = diethylamine.

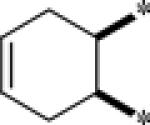

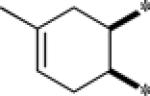

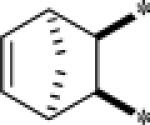

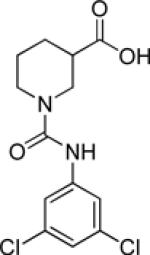

Lastly, the cyclohexyl moiety was modified in order to determine the optimal orientation of the acid and amide. Starting from the commercially available cyclic anhydrides 8a-k (Table 4), the desired target compounds were synthesized by ring opening of the anhydride with 3,5-dichloroaniline (THF, 55 °C, 15-56%)(Scheme 4). All of the cyclohexyl replacements that were evaluated were uniformly inactive, with the exception of the cyclohexene analog, 9e (2.7 μM, GluMax = 150%). However, substitution on the cyclohexene ring system again produced an inactive compound, 9f. Moving the carboxylic acid and the amide moieties one carbon away (1,3-orientation) also led to an inactive compound, 9i. An additional ring system that was evaluated was the piperidine-3-carboxylic acid, 9j. This series was synthesized by reacting the commercially available 3-piperidine carboxylic acid with 3,5-dichlorophenyl isocyanate. A number of compounds were synthesized; however, all compounds were inactive. Lastly, having shown the primary carboxamide was an active carboxyclic acid replacement, 9k was synthesized and evaluated. The primary carboxamide cyclohexene was also active and was equipotent with the acid analog (3.1 μM, GluMax = 94%).

Table 4.

| Compound | R,R′ | EC50 (μM) hmGluR44,a |

% Glu Max |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | -(CH2)4- | 0.75 | 127 |

| 9a | H,H | Inactive | |

| 9b | -(CH2)2- | Inactive | |

| 9c | -(CH2)3- | Inactive | |

| 9d | -(CH(CH3)2)- | Inactive | |

| 9e |  |

2.7 | 150 |

| 9f |  |

Inactive | |

| 9g |  |

Inactive | |

| 9h |  |

Inactive | |

| 9i |  |

inactive | |

| 9j |  |

inactive | |

| 9k |  |

3.1 | 94 |

Data for inactive compounds represents the average of at least one experiment performed in triplicate; active compounds were assessed in three independent experiments in triplicate.

Scheme 4.

Library synthesis of 9a-k. Reagents and conditions: (a) 3,5-dichloroaniline, THF, 55 °C (15-56%). All library compounds were purified by mass-directed prep LC where required.17,18

As was reported in our initial publication4, the two enantiomers of VU0155041 (1R,2S) and (1S,2R) were of equal potency and efficacy (1.1 μM, 6.7 fold shift and 1.1 μM, 8.6 fold shift, respectively). To determine if these new analogs displayed enantioselective receptor activation; the cyclohexyl carboxamide 5a, cyclohexene carboxylic acid 9e, and the cyclohexene carboxamide, 9k, were resolved into pure enantiomers by chiral HPLC. For both 5a and 9e, the resolved enantiomers were of equivalent potency and efficacy (for 5a, >5 μM, 5.4 fold shift; 2.4 μM, 4.4 fold shift and for 9e, 2.5 μM, GluMax = 76% and 2.7 μM, GluMax = 72%, respectively). However the (+)-isomer of 9k was 15-fold more potent than the (−)-isomer (2.1 μM, 5.5 fold shift and >30 μM, 3.6 fold shift, respectively).22

In conclusion, we report the SAR evaluation of a novel mGluR4 positive allosteric modulator, 2, that was recently shown to be active in two anti-Parkinsonian in vivo rodent models.4 The SAR around this scaffold proved to be very challenging in that limited modification of the original hit was tolerated. It was found that only substituted phenyl amides were tolerated with the optimal substitution being the 3,5-dichlorophenyl amide. In addition, carboxylic acid replacements were also evaluated with only the primary carboxamide having activity similar to the acid. Utilizing known carboxylic acid mimetics proved unfruitful in this scaffold. Lastly, modification of the cyclohexyl ring system allowed only minor modifications. In fact, only the cyclohexene derivative was active, and that compound exhibited a 3-fold loss of activity compared to the original hit. However, the cyclohexene ring system with the primary carboxamide showed specificity for one enantiomer ((+)-isomer) allowing for the identification of a compound with activity similar to the original lead (506 nM vs. 740 nM). The limited SAR in scaffolds that have been identified as allosteric modulators is a well-documented phenomenon in this area.11-13,16,23 Even though the SAR was limited around this scaffold, compound 2 has been shown to be efficacious in preclinical PD models further validating mGluR4 as a potential therapeutic treatment for alleviating PD symptoms.

Figure 2.

Areas of SAR exploration of VU0155041, 2.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Qingwei Luo and Rocio Zamorano for technical assistance with pharmacology assays and Emily L. Days, Tasha Nalywajko, Cheryl A. Austin and Michael Baxter Williams for their critical contributions to the HTS portion of the project and Matt Mulder, Chris Denicola and Sichen Chang for the purification of compounds utilizing the mass-directed HPLC system. This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health, the Michael J. Fox Foundation, the Vanderbilt Department of Pharmacology and the Vanderbilt Institute of Chemical Biology.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- 1.Conn PJ, Christopoulos A, Lindsley CW. Nature Rev. Drug. Dis. 2009;8:41. doi: 10.1038/nrd2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conn PJ, Jones CK, Lindsley CW. Trends Pharm. Sci. 2009;30:148. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marino MJ, Williams DL, Jr., O'Brien JA, Valenti O, McDonald TP, Clements MK, Wang R, DiLella AG, Kinney GG, Conn PJ. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2003;100:13668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1835724100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niswender CM, Johnson KA, Weaver CD, Jones CK, Xiang Z, Luo Q, Rodriguez AL, Marlo JE, de Paulis T, Thompson AD, Days EL, Nalywajko T, Austin CA, Williams MB, Ayala JE, Williams R, Lindsley CW, Conn PJ. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008;74:1345. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.049551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Battaglia G, Busceti CL, Molinaro G, Giagioni F, Traficante A, Nicoletti F, Bruno V. J. Neuroscience. 2006;26:7222. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1595-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopez S, Turle-Lorenzo N, Acher F, De Leonibus E, Mele A, Amalric M. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:6701. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0299-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sibille P, Lopez S, Brabet I, Valenti O, Oueslati N, Gaven F, Goudet C, Bertrand H-O, Neyton J, Marino MJ, Amalrie M, Pin J-P, Acher FC. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:3585. doi: 10.1021/jm070262c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Annoura H, Fukunaga A, Uesugi M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1996;6:763. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00516-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maj M, Bruno V, Dragic Z, Yamamoto R, Battaglia G, Inderbitzin W, Stoehr N, Stein T, Gasparini F, Vranesic I, Kuhn R, Nicoletti F, Flor PJ. Neuropharmacology. 2003;45:895. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00271-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hopkins CR, Lindsley CW, Niswender CM. Future Med. Chem. 2009;1:501. doi: 10.4155/fmc.09.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niswender CM, Lebois EP, Luo Q, Kim K, Muchalski H, Yin H, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008;18:5626. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.08.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams R, Niswender CM, Luo Q, Le U, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009;19:962. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.11.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engers DW, Niswender CM, Weaver CD, Jadhav S, Menon UN, Zamorano R, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW, Hopkins CR. J. Med. Chem. 2009 doi: 10.1021/jm9005065. DOI:10.1021/jm9005065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Compound 2 (VU0155041) is now available from TOCRIS bioscience (Cat. No. 3248).

- 15.Assay details: Cell culture-human mGluR4/Gqi5/CHO line. Human mGluR4 (hmGluR4)/CHO cells stably transfected expressing the chimeric G protein Gqi5 in pIRESneo3 (Invitrogen, C., CA) were cultured in 90% Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Media (DMEM), 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/ml penicillin/streptomycin, 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.3), 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM glutamine, 400 μg/ml G418 sufate (Mediatech, Inc., Herndon, VA) and 5 nM methotrexate (Calbiochem, EMD Chemicals, Gibbstown, NJ).; (30,000 cells/20 μl/well) were plated in black-walled, clear-bottomed, TC treated, 384 well plates (Greiner Bio-One, Monroe, North Carolina) in DMEM containing 10% dialyzed FBS, 20 mM HEPES, 100 units/ml penicillin/streptomycin, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Plating Medium). The cells were grown overnight at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2. During the day of assay, the medium was replaced with 20 μL of 1 μM Fluo-4, AM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) prepared as a 2.3 mM stock in DMSO and mixed in a 1:1 ratio with 10% (w/v) pluronic acid F-127 and diluted in Assay Buffer (Hank's balanced salt solution, 20 mM HEPES and 2.5 mM Probenecid (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO)) for 45 minutes at 37 °C. Dye was removed and replaced with 20 μL of Assay Buffer. Test compounds were transferred to daughter plates using an Echo acoustic plate reformatter (Labcyte, Sunnyvale, CA) and then diluted into Assay Buffer. Ca2+ flux was measured using the Functional Drug Screening System 6000 (FDSS6000, Hamamatsu, Japan). Baseline readings were taken (10 images at 1 Hz, excitation, 470±20 nm, emission, 540±30 nm) and then 20 μl/well test compounds were added using the FDSS's integrated pipettor. Cells were incubated with compounds for approximately 2.5 minutes and then an EC20 concentration of glutamate was applied; 2 minutes later an EC80 concentration of glutamate was added. For concentration-response curve experiments, compounds were serially diluted 1:3 into 10 point concentration response curves and were transferred to daughter plates using the Echo. Test compounds were again applied and followed by EC20 concentrations of glutamate. For fold shift experiments, compounds were added at 2X their final concentration and then increasing concentrations of glutamate were added in the presence of vehicle or the appropriate concentration of test compound. Curves were fitted using a four point logistical equation using Microsoft XLfit (IDBS, Bridgewater, NJ).

- 16.Zhao Z, Wisnoski DD, O'Brien JA, Lemaire W, Williams DL, Jr., Jacobsen MA, Wittman M, Ha SN, Schaffhauser H, Sur C, Pettibone DJ, Duggan ME, Conn PJ, Hartmann GD, Lindsley CW. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;17:1386. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.11.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leister W, Strauss K, Wisnoski D, Zhao Z, Lindsley C. J. Comb. Chem. 2003;5:322. doi: 10.1021/cc0201041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.All new structures were characterized by LCMS and/or 1H NMR and found to be in agreement with their structures.

- 19.Kimura T, Hamada Y, Stochaj M, Ikari H, Nagamine A, Abdel-Rahman H, Igawa N, Hidaka K, Nguyen J-T, Saito K, Hayashi Y, Kiso Y. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:2380. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.01.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohara Y, Imamiya E, Kubo K, Wada T, Inada Y, Naka T. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1995;5:1903. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kohara Y, Kubo K, Imamiya E, Wada T, Inada Y, Naka T. J. Med. Chem. 1996;39:5228–5235. doi: 10.1021/jm960547h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.HPLC conditions: AD chirapak column, 250 × 150 mmID, 20 mM particle size; solvent, 6% isopropanol/hexanes, 120 mL/min; 220 nM. RT = 12.7 min., (+)-isomer, [α]D +52.9 (c =1, MeOH); RT = 13.8 min., (−)-isomer, [α]D −47.1 (c = 1, MeOH).

- 23.O'Brien JA, Lemaire W, Wittmann M, Jacobsen MA, Ha SN, Wisnoski DD, Lindsley CW, Schaffhauser HJ, Rowe B, Sur C, Duggan ME, Pettibone DJ, Conn PJ, Williams DL., Jr. J. Pharm. Expt. Ther. 2004;309:568. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.061747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]