Abstract

Background

Left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) have been used as a bridge to cardiac transplantation and as destination therapy in patients with advanced heart failure. The period after LVAD support is associated with ventricular arrhythmias (VAs) despite ventricular unloading and such VAs can have a detrimental effect on survival. Despite the increasing use of LVAD, little is known regarding post-LVAD VAs at the molecular level and in vivo.

Methods

Forty-two patients who received LVAD over a 24-month period were evaluated and grouped on the basis of the presence or absence of VAs during LVAD support. We completed a comparative microarray analyses between six patients who developed ventricular tachycardia (VT) or ventricular fibrillation (VF) after LVAD support and six patients who did not develop VAs after LVAD.

Results

VAs occurred in 15 patients (35.7%) during LVAD support at a median post-LVAD day of 25.2. VAs were strongly associated with nonusage of a β-blocker post-LVAD (odds ratio of 7.04, P-value = 0.001). Analysis of a subset of patients who had VT or VF after LVAD placement showed a decrease in the expression of connexin 43 (0.48 ± 0.07), Na+/K+–ATPase (0.60 ± 0.05), and voltage-gated K+ channel Kv4.3 (0.42 ± 0.04), and an increase in Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (2.2 ± 0.4) and the structural genes: Titin (2.1 ± 0.2), laminin (1.7 ± 0.4), calsequestrin (1.8 ± 0.5), skeletal muscle isoform of troponin T (5.1 ± 0.9), and skeletal muscle isoform of troponin I (3.9 ± 0.7).

Conclusion

After LVAD, the increased risk of VAs is strongly associated with nonusage of β-blocker postoperatively.

Keywords: congestive heart failure, VT, electrophysiology, clinical

Introduction

Left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) have been used as a “bridge” to cardiac transplantation and as destination therapy in patients with advanced congestive heart failure. The early postoperative period after initiation of LVAD support of the failing human heart is associated with ventricular arrhythmias (VAs).1–3 This increased incidence of arrhythmogenesis after LVAD placement is still not well understood.

Acute unloading of the left ventricle has been reported to increase VAs in the early postoperative period because of changes in repolarization.1,2 In addition, it is well known that the failing heart undergoes reverse remodeling post-LVAD via specific genetic regulation. In fact, upregulation of sarcomeric genes and calcium-handling genes has been reported after LVAD.4 Furthermore, a change in the functional balance between the sarcoplasmic Ca2+–ATPase (SERCA) and the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) for (Ca2+) reuptake has been demonstrated after the LVAD support.5 In vivo animal models showed that the patterns of gene expression in unloaded heart induced a reexpression of fetal genes and that might contribute to the functional improvement of an unloaded failing heart. Also, the early changes induced by unloading were rapidly reversible upon reloading. These results provided evidence that the functional improvement of cardiac myocytes after LVAD therapy might be related to a switching in the expression of genes, including those controlling myocardial energetics.6

Whether this cardiac molecular adaptation to mechanical unloading could also be contributing to the ventricular arrhythmogenesis has not been yet studied. This could potentially be an important contributor to post-LVAD arrhythmogenesis and it goes beyond the impact of myocardial inflammation and wound healing as a focus for ventricular reentrant circuit after LVAD implants. A better understanding of the characteristics that predispose mechanically supported patients to VA may lead to innovative strategies in VA prevention and improved clinical outcomes in a patient population that will surely expand in the coming years. This will have a significant clinical impact, especially since recent data showed that post-LVAD VAs are associated with greater mortality that can be as high as 54% if the occurrence is within a week of LVAD support.7

Methods

Study Population

We conducted a retrospective cohort study and reviewed the pre- and post-LVAD course of 42 adult patients who received LVAD over a 24-month period. This included a review of LVAD-supported patients’ daily medical, nursing, and telemetry records as well as implantable cardioverter defibrillator (CD) interrogations for documented evidence of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT), sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT), or ventricular fibrillation (VF) for 1 week preoperatively and postoperatively. Clinically significant VA was defined as VF, sustained VT, or NSVT with symptoms requiring antiarrhythmic therapy.

NSVT was defined as greater than three consecutive ventricular ectopic beats lasting less than 30 seconds at a rate greater than 100 bpm, and sustained VT was defined as greater than 30 seconds of ventricular ectopic beats with a rate greater than 100 bpm. Patients who underwent LVAD placement were on a cardiac unit with continuous telemetry monitoring. The duration, timing, and intervention for each tachycardia picked up by the telemetry alarms were reviewed and verified that it was indeed VF, VT, or NSVT and then recorded. Furthermore, in the subset of patients who had an ICD, the density of arrhythmias was assessed upon interrogation of the ICDs.

Patients who did not have evidence of VF, VT, or NSVT postoperatively in their daily medical, nursing, and 24-hour daily telemetry records and ICD interrogations were considered to be VA-free after LVAD placement. Available LVAD flows and daily electrolyte values (potassium and magnesium) were recorded for each patient. In none of these 42 patients, VA was an indication for LVAD placement.

Clinical Variables

We obtained demographic and clinical variables on the LVAD-supported patients. These variables included age, gender, LV ejection fraction (LVEF), duration and etiology of heart failure, history of ICD, preoperative medication use within 48 hours of LVAD placement, postoperative medications, antiarrhythmic therapy before and after LVAD placement, and other pertinent medical history. Cardiac hemodynamics were measured with a Swan-Ganz catheter before (<24 hours before surgery) and after device placement (<24 hours postoperatively). LVEF, as measured by echocardiography within 1 month before LVAD placement, was recorded. Furthermore, temporal changes in the surface 12-lead electrocardiogram were examined before and after LVAD placement.

Tissue Samples

Six patients who developed post-LVAD VA were studied further. Those patients had sustained VT or VF. Three patients had ischemic cardiomyopathy and three patients had nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Under protocols approved by the institutional review board, tissue sections from the left ventricular apex of these patients were obtained at the time of LVAD insertion (pre-LVAD) and from the LV free wall of those same patients at the time of cardiac explantation (post-LVAD). These tissue sections were compared to those from six patients who did not develop VA after LVAD placement. Tissue slices from the patients were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Microarray Procedures

Total RNA was extracted from the human hearts in each experimental sample using TRIzol (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. RNA was resuspended in diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated H2O and further purified using the Qiagen (Chatsworth, CA, USA) RNeasy total RNA isolation kit. RNA was quantified and was used to generate cDNA using the Superscript Choice system (Invitrogen) according to the Affymetrix protocol (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Resulting cDNA was used to generate biotin-labeled cRNA using the ENZO Bioarray High Yield transcript labeling kit (Affymetrix). cRNA (20 μg) was fragmented in fragmentation buffer [40 mM Tris (pH 8.1), 100 mM potassium acetate, 30 mM magnesium acetate] for 35 minutes at 94°C. The quality of the cRNA was checked by hybridization to test three arrays (Affymetrix).

After the purification round, in vitro cRNA was fragmented in buffer containing magnesium at 94°C and then hybridized onto the Affymetrix U133A GeneChip microarray, which contains 22,283 probe sets. Briefly, 20-μg fragmented cRNA was added along with control cRNA (BioB, BioC, and BioD), herring sperm DNA, and BSA to the hybridization buffer. The hybridization mixture was heated at 99°C for 5 minutes, incubated at 45°C for 5 minutes, and injected into the microarray. After hybridization at 45°C for 16 hours, the array was washed and stained with the Affymetrix Fluidics Protocols-antibody amplification for Eukaryotic Targets, and scanned using an Affymetrix microarray scanner system at 570 nm.

Data Analysis

We calculated intensity ratios of the samples for each of the 12 patients. The intensity ratio calculated for each gene reflects the relative abundance of mRNA in the experimental sample versus a reference sample. The use of a common reference microarray allows the comparison of the relative expression level of each gene across all the experimental samples (arrays). A 1.5 cutoff value for the ratios was used. (Thus the upper cutoff value is 1.5 and the lower cutoff value is 1/1.5 = 0.66.) Genes were normalized and mean-centered, then hierarchical clustering was applied to the genes axis using the unweighted pair-group method with complete linkage as implemented in Cluster. The intensity ratio (post-LVAD/pre-LVAD) of genes was used to reflect the change in gene expression after LVAD support. Other researchers who studied the effect of gene expression after LVAD support used this method.4 The relative intensity was used to compare the intensity ratios from the patients who developed VAs post-LVAD to those who did not develop VAs after LVAD placement.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS 13 statistical program was used (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous data are presented as mean ± SD. A multivariate logistic regression was performed to determine independent predictors for VA after LVAD placement. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical Characteristics

Our study population included 42 patients with a mean age of (54.3 ± 15.7) years. Thirty-five patients were male, accounting for 83.3% of the population. The mean LVEF was (18.8 ± 11.3)%. Patients had a clinical CHF for mean months of (41.4 ± 39.5). Approximately 54.8% had an ischemic CHF etiology. Their clinical characteristics are shown in Table I.

Table I.

Characteristics of the 42 Patients Who Underwent LVAD Placement

| Variable | Result | VA Group (N = 15) | Post-LVAD with no VA (N = 27) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 54.3 ± 15.7 | 50.1 ± 14.1 | 56.6 ± 16.3 |

| Gender (% male) | 35 (83.3%) | 14 (93.3%) | 21 (77.8%) |

| LV ejection fraction | 18.8 ± 11.3 | 16.3 ± 5.2 | 20.5 ± 14.0 |

| Clinical CHF (months) | 41.4 ± 39.5 | 49.1 ± 50.3 | 34.3 ± 25.6 |

| Etiology of CHF | |||

| Ischemic DCMP | 23 (54.8%) | 9 (60.0%) | 14 (51.9%) |

| Viral DCMP | 6 (14.3%) | 3 (20.0%) | 3 (11.1%) |

| Idiopathic DCMP | 4 (9.5%) | 1 (6.7%) | 3 (11.1%) |

| Familial DCMP | 2 (4.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (7.4%) |

| Valvular DCMP | 2 (4.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (7.4%) |

| AL Amyloid RCMP | 2 (4.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (7.4%) |

| Transthyretin Amyloid RCMP | 1 (2.4%) | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Peripartum DCMP | 1 (2.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.7%) |

| EtOH DCMP | 1 (2.4%) | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| History of ICD | 14 (33.3%) | 8 (53.3%) | 6 (22.2%) |

| Pre-LVAD antiarrhythmic therapy | 19 (45.2%) | 7 (46.7%) | 12 (44.4%) |

| Amiodarone | 16 (38.1%) | 6 (40.0%) | 10 (37.0%) |

| Lidocaine | 8 (19.0%) | 2 (13.3%) | 6 (22.2%) |

| Post-LVAD antiarrhythmic therapy | 5 (11.9%) | 2 (13.3%) | 3 (11.1%) |

| Pre-LVAD hemodynamic measurements | |||

| Pre-LVAD CO (L/minute) | 3.4 ± 1.4 | 3.4 ± 1.1 | 3.5 ± 1.8 |

| Pre-LVAD CVP (mmHg) | 17.7 ± 4.1 | 17.8 ± 4.7 | 17.7 ± 2.5 |

| Pre-LVAD sPAP (mmHg) | 55.2 ± 21.7 | 58.1 ± 26.3 | 53.8 ± 27.8 |

| Pre-LVAD dPAP (mmHg) | 28.5 ± 13.5 | 32.5 ± 17.8 | 22.6 ± 6.3 |

| Pre-LVAD mPAP (mmHg) | 38.6 ± 15.7 | 40.4 ± 12.5 | 33.0 ± 2.8 |

| Pre-LVAD PCWP (mmHg) | 26.9 ± 10.3 | 24.4 ± 12.7 | 27.6 ± 8.4 |

| Pre-LVAD mAP (mmHg) | 78.8 ± 6.7 | 80.0 ± 7.8 | 76.5 ± 4.9 |

| Pre-LVAD VT | 15 (35.7%) | 9 (60.0%) | 6 (22.2%) |

| Preoperative milrinone | 9 (21.4%) | 6 (40.0%) | 3 (11.1%) |

| Preoperative dobutamine | 21 (50%) | 10 (66.7%) | 11 (40.7%) |

| Preoperative dopamine | 10 (23.8%) | 6 (40.0%) | 4 (14.8%) |

| Postoperative inotropic support | 3 (7.1%) | 1 (6.7%) | 2 (7.4%) |

| Preoperative β-blocker | 4 (9.5%) | 2 (13.3%) | 2 (7.4%) |

| Postoperative β-blocker* | 14 (33.3%) | 1 (6.7%) | 13 (48.1%) |

| Digoxin | 8 (19.0%) | 7 (46.7%) | 1 (3.7%) |

| Diuretic | 18 (42.9%) | 10 (66.7%) | 8 (29.6%) |

| Spironolactone | 9 (21.4%) | 4 (26.7%) | 5 (18.5%) |

| Vasodilator therapy | 7 (16.7%) | 4 (26.7%) | 3 (11.1%) |

| ACE inhibitor | 5 (11.9%) | 2 (13.3%) | 3 (11.1%) |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker | 2 (4.8%) | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (3.7%) |

| IABP use | 21 (50%) | 8 (53.3%) | 13 (48.1%) |

| Duration of VAD support (days) | 43.5 ± 36.9 | 43.0 ± 32.1 | 43.6 ± 17.5 |

Continuous variables are expressed as mean + SD.

Statistically significant.

VT Prevalence

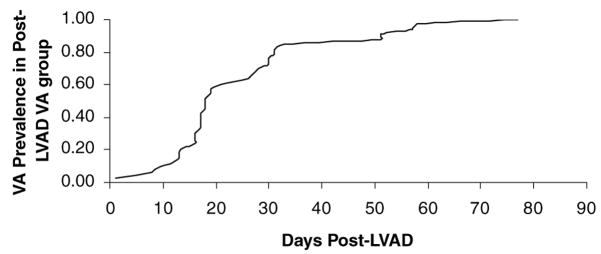

Of the 42 patients in our study, 15 patients had post-LVAD VAs (35.7%): 10 patients had monomorphic NSVT (66.7%) and five patients had sustained VT (33.3%). The five patients who developed sustained monomorphic VT had syncope, three of those patients required electrical cardioversion to normal sinus rhythm, and in the other two patients who had ICDs, VT was terminated by anti-tachycardia pacing (three burst pacing in one patient and ramp pacing in the other patient). None of these patients required further electrophysiologic study or catheter ablation. Of the 10 patients who developed NSVT, nine were symptomatic with patients developing palpitations or presyncope. In all of these patients, an antiarrhythmic was started or the dose was increased. In one patient who developed NSVT after LVAD, the NSVT degenerated into VF that was not terminated by defibrillation and the patient died. These VAs occurred at a median post-LVAD day of 25.2 (Table II). The prevalence of VT as a function of post-LVAD days is shown in Figure 1.

Table II.

Characteristics of the VAs in Patients after LVAD Placement (N = 15)

| Variable | Result |

|---|---|

| Type of VA | |

| NSVT, monomorphic | 10 (66.7%) |

| VT, monomorphic | 5 (33.3%) |

| Number of ventricular beats | 10.9 ± 6.3 |

| Median postoperative day | 25.1 ± 16.6 |

| Prolonged QTc before and after episodes (>450 ms) | 1 (2.4%) |

| Abnormal K or Mg before and after episodes | 0 (0.0%) |

| Clinical manifestation | |

| Palpitations or presyncope | 9/15 (60.0%) |

| Syncope | 5/15 (33.3%) |

| Death | 1/15 (6.7%) |

| Intervention | |

| Pharmacological | |

| β-blocker started | 2/15 (13.3%) |

| Antiarrhythmic started or dose increased | 14/15 (93.3%) |

| Electrical | |

| Antitachycardia pacing | 2/15 (13.3%) |

| DC cardioversion | 3/15 (20.0%) |

| Defibrillation | 1/15 (6.7%) |

| Electrophysiological (catheter ablation) | 0/15 (0.0%) |

Figure 1.

Prevalence of VA as functions of days post-LVAD.

Predictors of Ventricular Arrhythmias

Nonusage of a β-blocker post-LVAD was strongly associated with VAs with an odds ratio of 7.04 (P-value =0.001). The odds ratios of preoperative VA, pre-LVAD antiarrhythmic usage, ischemic congestive heart failure (CHF) etiology, postoperative electrolyte abnormality, and postoperative inotropic support for post-LVAD VA were 1.60 (P-value = 0.105), 1.06 (P-value = 0.251), 1.24 (P-value = 0.297), 2.23 (P-value = 0.092), and 0.93 (P-value = 0.564), respectively (Table III).

Table III.

Independent Predictors of VAs after LVAD Placement

| Risk Factor | Odds Ratio (OR) [P value] |

|---|---|

| Pre-LVAD antiarrhythmic usage | 1.06 [P = 0.251] |

| Preoperative VA | 1.60 [P = 0.105] |

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 1.24 [P = 0.297] |

| Postoperative inotropic support | 0.93 [P = 0.564] |

| Postoperative electrolyte abnormality | 2.23 [P = 0.092] |

| Nonusage of β-blocker post-LVAD | 7.04 [P = 0.001] |

Gene Expression Changes in Patients with VAs during LVAD Support

Following LVAD placement a total of 113 gene transcripts were upregulated according to our criteria and 46 gene transcripts were downregulated. We performed hierarchical clustering method and classified the genes into eight functional groups: (1) transcription factors, (2) signaling, (3) channels and transporters, (4) metabolism, (5) cell cycle/apoptosis, (6) cytoskeletal, (7) cytokines, and (8) cell defense. These were: 27% for transcription factors, 18% for signaling proteins, 13% for channels and transporters, 11% metabolism, 10% cell cycle/apoptosis, 9% cytoskeletal, 7% for cytokines, and 5% for cell defense. We were interested in changes of ionic channels and structural proteins that can specifically affect calcium handling and intercellular connection. There were specifically interesting changes that were noted that would change the unloaded hearts arrhythmic potential.

Comparing tissue sections of six patients with VT or VF post-LVAD to those from six patients who did not develop VAs after LVAD placement, the post-LVAD group with VT or VF had a decrease in connexin 43 (C×43) expression (0.48 ± 0.07), a decrease in Na+/K+–ATPase (0.60 ± 0.05), a decrease in the voltage-gated K+ channel Kv4.3 (0.42 ± 0.04), and a substantial increase in the NCX (2.2 ± 0.4). Structural genes were also increased in the post-LVAD VT or VF group: Titin (2.1 ± 0.2), laminin (1.7 ± 0.4), and calsequestrin (1.8 ± 0.5), including skeletal isoform of troponin T (5.1 ± 0.9), and skeletal muscle isoform of troponin I (3.9 ± 0.7).

Discussion

Our study showed that 35.7% of patients had VAs after LVAD placement. A study from Columbia University showed that 35.2% of patients developed post-LVAD VAs.3 In addition, a recent study from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center reported an incidence of 22% of VAs after LVAD support.7 However, while other researchers found that the majority of the VAs occurred by the first week post-LVAD, our study revealed that the median of post-LVAD VAs occurrence was around 3.5 weeks from the LVAD placement.3 Around 93.3% of the post-LVAD VAs were symptomatic (palpitations/presyncope/syncope) and one patient died after the NSVT degenerated into VF and failed defibrillation.

Further subset study on the patients who developed VT or VF during LVAD support showed remodeling in the NCX, C×43, Na+/K+ ATPase and the voltage-gated potassium channel Kv4.3. The present study adds to the current knowledge base by identifying these molecular changes that have not been previously reported. In fact, the mechanical unloading of the myocardium during LVAD support causes alterations in the ion channels involved in calcium handling and, as our subset study shows, alters certain ion transporting genes and structural genes that may render the heart more proarrhythmic. Other investigators reported as well an increased expression of the cardiomyocyte sarcolemmal NCX in patients with VAs during LVAD.1,5,8–17 This NCX upregulation would increase intracellular sodium influx and predisposes to delayed after depolarization.

Our study showed as well a downregulation of C×43 after LVAD support. C×43 downregulation leads to decreased electrical conduction velocity and has been associated with VT.18–22 C×43 knock-out mice have normal heart structure and contractile function; they die suddenly from spontaneous VT.18–22 In a pacing-induced heart failure model reduced C×43 expression produced uncoupling between transmural muscle layers, leading to slowed conduction and marked dispersion of repolarization between epicardial and deeper myocardial layers. This refractoriness heterogeneity is a substrate for reentry circuits leading to tachyarrhythmias.23

In addition to the gap junction downregulation and the NCX upregulation in patients with VAs during LVAD support, our study showed a downregulation in the Na+/K+ ATPase and the voltage gated potassium channel Kv4.3. The combination of changes of NCX and Kv4.3 induces an increase in action potential duration.24–26 The dispersion of the action potential duration and the reduction of the repolarization reserve would predispose to early after depolarization and increase the potential for tachycardia in the unloaded hearts.

Independent predictors of VAs after LVAD were identified using multivariate logistic regression. The occurrence of VAs during LVAD support was higher with postoperative electrolytes abnormality (K+, Mg2+), preoperative VA, pre-LVAD antiarrhythmic use, or if the etiology of the cardiomyopathy is ischemic though there was no statistical significance. Having preoperative VA puts the patients at a higher risk of having post-LVAD VT with an odds ratio of 1.6 though it was not statistically significant (P-value = 0.105).

Finally, the present study adds significantly to the current knowledge base by identifying a previously unreported preoperative clinical variable that is highly predictive of outcomes in the VAD-supported patient. In fact, if patients after LVAD are on no β-blockers, the multivariate regression analysis showed that the odds ratio of developing VAs is 7.04 (P-value = 0.001), which is clinically and statistically significant. None of the previously published studies associated VAs during LVAD support with β-blocker usage. The majority of patients who required LVAD support had decompensated congestive heart failure requiring inotropic support and in that setting β-blockers were not used. However, when these patients had LVAD implant, the use of β-blockers was left at the discretion of the treating physician. In this study, one-third of the patients were on β-blockers post-LVAD. Other researchers reported their results from patients after LVAD implant and the use of β-blockers was lower (25%; three out of 12 patients).4

The cardiac adrenergic receptors (AR) are G-protein-coupled transmembrane receptors. On binding to ligands, the G proteins (Gs) dissociate from the intracellular domain of the receptor to propagate signals by modulating the activity of downstream effector molecules such as adenylate cyclase, phospholipases, and ion channels. The β1-AR and β2-AR are both normally coupled to the stimulatory Gs, and through this protein, they activate adenylate cyclase, augmenting myocyte contractility but also inducing myocyte hypertrophy and failure in the case of the β1-AR. This regulation of cell growth involves multiple downstream molecules including mitogen-activated protein kinases.27 Earlier studies showed that β1-AR antagonists do not change the absolute levels of gene expression of adenylate cyclase subtypes in human atria.28

Recent studies showed some of the benefits of β-AR blocker treatment in patients with CHF via a reduction of pathological changes in cardiac β-AR-G-protein(s)-adenylyl cyclase system driven by the increased sympathetic system. Cardiac β1-AR are upregulated, and amount and activity of cardiac G(i)-protein and G-protein-coupled receptor kinase (GRK) are decreased, resulting in increased cardiac β-AR functional responsiveness.29 Some of the beneficial effects of β-blockers are mediated by β-arrestin activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases.30 Recently, carvedilol has been shown to stimulate β-arrestin-mediated signaling and might contribute to the special efficacy of carvedilol in the treatment of heart failure.31

Currently, the guidelines do not mandate patients to be on a β-blocker post-LVAD. However, the use of β-blocker in patients post-LVAD might suppress the arrhythmogenesis and further randomized clinical trials on a larger population size will be able to give an answer on benefit with β-blocker after LVAD placement, especially that the occurrence of VAs after LVAD implantation has an important impact on the clinical outcome of patients. In fact, it is associated with greater mortality that can be as high as 54% if the occurrence is within a week of LVAD support.7 Thus, the clinical impact of this study would be to continue β-blockers in patients at least in the early postoperative period after their decompensated heart failure was supported with an LVAD.

Our study was limited by its retrospective nature. The results of this study are considered primarily as hypothesis generating. The findings need to be confirmed prospectively in a multicenter study. Furthermore, the mechanisms of VAs warrant further investigation. Myocyte studies are confounded by regional variability in myocytes, and differences in disease as well as patient medications. Further ex vivo and in vivo studies will help to determine the effect of β-blockers on the gene expression changes observed and arrhythmogenecity.

Conclusion

In summary, the present study shows an increased risk of VAs after LVAD placement. In addition, it identifies a modifiable risk factor that predicts clinical outcomes in patients after mechanical circulatory support. In fact, VAs after LVAD support are strongly associated clinically with the nonusage of β-blocker postoperatively. Based upon the results of this study, we suggest that β-blockers need to be started in patients after VAD placement when there are off inotropes to optimize their clinical outcomes.

The transcript profiling we performed on a small number of patients who developed VT or VF showed a distinct pattern of changes of specific ion transporting genes and structural genes in patients after LVAD implantation rendering the heart more proarrhythmic.

Footnotes

Presented as an abstract at the 28th Annual Scientific Sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society, May 10, 2007, Denver, Colorado.

Conflict of Interest/Financial Disclosure: None.

References

- 1.Harding JD, Piacentino V, III, Rothman S, Chambers S, Jessup M, Margulies KB. Prolonged repolarization after ventricular assist device support is associated with tachycardia in humans with congestive heart failure. J Card Fail. 2005;11:227–232. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2004.08.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grzywacz FW, Piacentino V, III, Marble J, Bozorgnia B, Gaughan JP, Rothman SA, Margulies KB. Effect of acute unloading via head-up tilt on QTc prolongation in patients with ischemic or non-ischemic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:412–415. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ziv O, Dizon J, Thosani A, Naka Y, Magnano A, Garan H. Effects of left ventricular assist device therapy on ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1428–1434. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodrigue-Way A, Burkhoff D, Geesaman BJ, Golden S, Xu J, Pollman MJ, Donoghue M, et al. Sarcomeric genes involved in reverse remodeling of the heart during left ventricular assist device support. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2003.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaudhary KW, Rossman EI, Piacentino V, III, Kenessey A, Weber C, Gaughan JP, Ojamaa K, et al. Altered myocardial Ca2 +cycling after left ventricular assist device support in the failing human heart. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:837–845. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Depre C, Shipley GL, Chen W, Han Q, Doenst T, Moore ML, Stepkowski S, et al. Unloaded heart in vivo replicates fetal gene expression of cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med. 1998;4:1269–1275. doi: 10.1038/3253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bedi M, Kormos R, Winowich S, McNamara D, Mathier M, Murali S. Ventricular arrhythmias during left ventricular assist device support. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:1151–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Altemose G, Gritsus TV, Jeevanandam V, Goldman B, Margulies KB. Altered myocardial phenotype after mechanical support in human beings with advanced cardiomyopathy. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1997;16:765–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dipla K, Mattiello JA, Jeevanandam V, Houser SR, Margulies KB. Myocyte recovery after mechanical circulatory support in humans with end-stage heart failure. Circulation. 1998;97:2316–2322. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.23.2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zafeiridis A, Jeevanandam V, Houser SR, Margulies KB. Regression of cellular hypertrophy after left ventricular assist device support. Circulation. 1998;98:656–662. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.7.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flesch M, Margulies KB, Mochmann HC, Engel D, Sivasubramanian N, Mann DL. Differential regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinases in the failing human heart in response to mechanical unloading. Circulation. 2001;104:2273–2276. doi: 10.1161/hc4401.099449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harding JD, Piacentino V, III, Gaughan JP, Houser SR, Margulies KB. Electrophysiological alterations after mechanical circulatory support in patients with advanced cardiac failure. Circulation. 2001;104:1241–1247. doi: 10.1161/hc3601.095718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen X, Piacentino V, III, Furukawa S, Goldman B, Margulies KB, Houser SR. L-type Ca2+ channel density and regulation are altered in failing human ventricular myocytes and recover after support with mechanical assist devices. Circ Res. 2002;91:517–524. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000033988.13062.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Margulies KB. Reversal mechanisms of left ventricular remodeling, lessons from left ventricular assist device experiments. J Card Fail. 2002;8:S500–S505. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2002.129264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Y, Park S, Li Y, Missov E, Hou M, Han X, Hall JL, et al. Alterations of gene expression in failing myocardium following left ventricular assist device support. Physiol Genomics. 2003;14:251–260. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00022.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall JL, Grindle S, Han X, Fermin D, Park S, Chen Y, Bache RJ, et al. Genomic profiling of the human heart before and after mechanical support with a ventricular assist device reveals alterations in vascular signaling networks. Physiol Genomics. 2004;17:283–291. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00004.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Margulies KB, Matiwala S, Cornejo C, Olsen H, Craven WA, Bednarik D. Mixed messages, transcription patterns in failing and recovering human myocardium. Circ Res. 2005;96:592–599. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000159390.03503.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saez JC, Nairn AC, Czernik AJ, Fishman GI, Spray DC, Hertzberg EL. Phosphorylation of connexin 43 and the regulation of neonatal rat cardiac myocyte gap junctions. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:2131–2145. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee P, Morley G, Huang Q, Fischer A, Seiler S, Horner JW, Factor S, et al. Conditional lineage ablation to model human diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11371–11376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ai Z, Fischer A, Spray DC, Brown AM, Fishman GI. Wnt-1 regulation of connexin43 in cardiac myocytes. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:161–171. doi: 10.1172/JCI7798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gutstein DE, Morley GE, Fishman GI. Conditional gene targeting of connexin43, exploring the consequences of gap junction remodeling in the heart. Cell Commun Adhes. 2001;8:345–348. doi: 10.3109/15419060109080751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gutstein DE, Morley GE, Vaidya D, Liu F, Chen FL, Stuhlmann H, Fishman GI. Heterogeneous expression of Gap junction channels in the heart leads to conduction defects and ventricular dysfunction. Circulation. 2001;104:1194–1199. doi: 10.1161/hc3601.093990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poelzing S, Rosenbaum DS. Altered connexin43 expression produces tachycardia substrate in heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H1762–1770. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00346.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ranu HK, Terracciano CM, Davia K, Bernobich E, Chaudhri B, Robinson SE, Bin Kang Z, et al. Effects of Na (+)/Ca(2+)-exchanger over-expression on excitation-contraction coupling in adult rabbit ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:389–400. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lebeche D, Kaprielian R, del Monte F, Tomaselli G, Gwathmey JK, Schwartz A, Hajjar RJ. In vivo cardiac gene transfer of Kv4.3 abrogates the hypertrophic response in rats after aortic stenosis. Circulation. 2004;110:3435–3443. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000148176.33730.3F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lebeche D, Kaprielian R, Hajjar RJ. Modulation of action potential duration on myocyte hypertrophic pathways. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;40:725–735. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hajjar RJ, MacRae CA. Adrenergic-receptor polymorphisms and heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1196–1198. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe020105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang T, Brown MJ. Influence of beta1-adrenoceptor blockade on the gene expression of adenylate cyclase subtypes and beta-adrenoceptor kinase in human atrium. Clin Sci (Lond) 2001;101:211–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brodde OE. Beta-adrenoceptor blocker treatment and the cardiac beta-adrenoceptor-G-protein(s)-adenylyl cyclase system in chronic heart failure. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2007;374:361–372. doi: 10.1007/s00210-006-0125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azzi M, Charest PG, Angers S, Rousseau G, Kohout T, Bouvier M, Piñeyro G. Beta-arrestin-mediated activation of MAPK by inverse agonists reveals distinct active conformations for G protein-coupled receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11406–11411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1936664100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wisler JW, DeWire SM, Whalen EJ, Violin JD, Drake MT, Ahn S, Shenoy SK, et al. A unique mechanism of beta-blocker action: Carvedilol stimulates beta-arrestin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16657–16662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707936104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]