Abstract

As a result of the pandemic of human immunodeficiency virus infection, more academic physicians involved in research are working in resource-limited settings, especially in the field of infectious diseases. These researchers are often located in close proximity to health care facilities with serious workforce shortages. Because institutions and funders support global health research, they have the opportunity to make a lasting impact on the health system by training local health workers where the research is being conducted. Academic researchers who spend clinical time in local health care centers and who teach and mentor students as part of academic social responsibility will build capacity, an investment that will yield dividends for future generations.

I will remember that I remain a member of society, with special obligations to all my fellow human beings, those sound of mind and body as well as the infirm. If I do not violate this oath, may I enjoy life and art, respected while I live and remembered with affection thereafter. May I always act so as to preserve the finest traditions of my calling and may I long experience the joy of healing those who seek my help.

—Louis Lasagna, Academic Dean of the School of Medicine at Tufts University, 1964

As academicians, we pursue research to answer questions that will advance the field of medicine. As clinicians, we aspire to improve the health of others while never inflicting harm. With the epidemic of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and AIDS and especially in the subspecialty of infectious diseases, physician-scientists in resource-limited settings face challenging moral dilemmas where detriment-benefit assessments are not simple. Although research is often best performed in places where diseases such as HIV infection, tuberculosis, and malaria are most prevalent, these places are often within severely resource-limited countries where the most impoverished citizens are disproportionately affected by these diseases. As stated so eloquently by Omonzejele, a Nigerian ethicist, “...physicians in developing countries are confronted with harsher forms of moral dilemmas than their counterparts in the developed countries if they must adhere in totality to the obligation of nonmaleficence” [1]. Accordingly, if we do nothing in situations where we perceive clear medical need, does this constitute inflicting harm? The ethical obligation to provide health care while performing health research has been debated in the medical literature [2]. An additional form of beneficence is the provision of health education as a means of contributing to those from whom we intend to learn. Although many academicians aspire to become a “triple threat”—physician-scientists who maintain a clinical practice, teach students well enough to win their respect, and conduct research of a caliber high enough to obtain self-supporting grants [3]—it has become increasingly more difficult to become a triple threat. Herein, we propose the concept of academic social responsibility, whereby academicians embrace educational opportunities to redefine the triple threat and to maximize each individual’s impact on trainees in every setting.

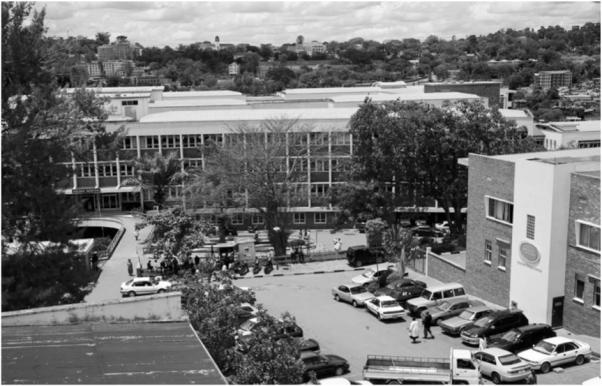

In 2004, the Infectious Diseases Institute, a new facility dedicated to the care of patients diagnosed with infectious diseases such as HIV infection and tuberculosis, was opened at Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda. The concept of a dedicated new facility grew from a collaborative effort that started with a group of Ugandan and North American physicians who called themselves the Academic Alliance for AIDS Care and Prevention [4]. By enhancing the research and clinical opportunities at the Infectious Diseases Institute for the faculty, medical residents, and medical students of Makerere University, the Academic Alliance and their new foundation, the Accordia Foundation for Global Health, are helping to reverse the trend of African health care professionals pursuing academic opportunities abroad. The Infectious Diseases Institute has facilities designed to accommodate research, training, laboratory services, and ambulatory clinical care for >13,000 HIV-infected patients. It is located adjacent to Mulago Hospital, which is the publicly funded national tertiary referral hospital caring for >1500 patients (figure 1).

Figure 1.

The 50-yard corridor linking Mulago Hospital (left) and the Infectious Diseases Institute at Makerere University (right) in Kampala, Uganda. (photo courtesy of Dr. Charles Steinberg)

The evident disparity between donor-funded and public facilities has become a common scenario in resource-limited settings as global health has become a funded priority. Highly trained health professionals are faced with a brittle health care infrastructure manifested by hospitals, such as Mulago, that are taxed by the over-whelming demand caused largely by the HIV epidemic and undermined by perpetual understaffing and insufficient resources [5, 6]. Furthermore, for the physicians who work both at the Infectious Diseases Institute and in the hospital, the clinical demand, albeit high at both sites, is more pressing at the hospital, where there is a constant stream of high-acuity patients. For health professionals, this proximal disparity represents an opportunity to build capacity through training and to offer our skills and expertise in an effort to fill the human resource gap.

Many of the medical centers of excellence in wealthy nations are also situated in areas of deprivation caused by poverty and limited resources. Consequently, academic physicians in these settings may face ethical questions similar to those confronting us. A global consensus exists that medical research is overall an endeavor worthy of a professional career with substantial rewards. The real crux of the matter is how to emphasize the strategic importance of taking time to teach others in an environment with overwhelming need and how to move beyond our research activities in order to revive the humanistic side often overshadowed by career goals. How can academic physicians in a well-funded outpatient unit that adheres to an international standard respond to need in the “neighborhood” where they perform their clinical and laboratory research, whether in resource-limited settings or in the developed world? When institutes such as the Infectious Diseases Institute provide free clinical services to patients from the surrounding community, is their obligation to the acutely ill patients across the corridor mitigated? On HIV wards in sub-Saharan Africa, where underresourced public hospitals often lead to demoralized staff, taking care of in-patients with end-stage AIDS has been an Oslerian exercise in watching the course of death and dying [7]. In this light, one could argue that by improving the health of outpatients through treatment, the burden of patients in the hospital decreases. Nonetheless, we believe that a contribution of clinical time in a place where there is vast unmet need has the potential to pay dividends for the next generation. A contribution, no matter how small, is a step forward. Perhaps taking the time to reinforce the importance of a complete and thoughtful history and physical examination to trainees can lead to systems of accountability for all who care for patients.

A dilemma arises, however, with the issue of how much unremunerated time is required to achieve the goal of academic social responsibility. The accountability of time to funding agencies, combined with clear expectations for evidence of scholarship, inevitably results in a downward prioritization of academic social responsibility. It is commonplace to hear senior staff reminisce about the era of the triple threat, when being an excellent academician meant being an astute clinician, researcher, and teacher. Most argue that aspiring to this standard in today’s academic environment is difficult enough without adding another dimension to time that shifts the focus from funded research to providing a service to a busy ward in the hospital or unit next door.

We believe that, as the international code of medical ethics states, “A doctor must always bear in mind the obligation of preserving life” [6]. To help their staff abide by this code, academic tertiary care centers in the developed world should recognize the need for academic social responsibility. Institutional and professional society leaders in the developed world could require academic social responsibility from all staff, make time available to faculty, find ways to measure these contributions, and ultimately help fund opportunities in underserved communities or the developing world [8]. Moreover, academic institutions and funding agencies could increase the indirect cost rate for low-income countries to strengthen infrastructure at health units in the vicinity of the project sites. In this way, organizations conducting research at academic institutions can help drive health care infrastructure (e.g., the Infectious Diseases Institute and the Harvard AIDS Initiative), and, conversely, initiatives founded to deliver health care to underserved areas can ultimately engage in operational research to inform programmatic decisions (e.g., Medecins Sans Frontieres and Partners in Health). As institutions seek more resources for global health research, they must not overlook the opportunity to make a lasting impact on the health system where the research is being conducted.

Resurrect and resource a new triple threat—an academician (researcher or clinician educator) who embraces academic social responsibility and effectively mentors to inspire these skills in trainees. We posit that the world would be a better place for it and the dividends limitless.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the editorial contributions of James D. Campbell and the Accordia Global Health Foundation and their vision in creating the Infectious Diseases Institute.

Financial support. National Institutes of Health (1R01HL090312-01 to Y.C.M.); the Johns Hopkins Center for Global Health (to T.C.Q. and Y.C.M.); the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases and Pathology (to D.T. and Y.C.M.); the Department of Medicine at Trinity College (to C.M.); the University of Virginia Center for Global Health and Division of Infectious Diseases and International Health (to S.T.J.); and the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (to T.C.Q.).

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest. A.R. has received an honorarium from Merck through his department. All other authors: no conflicts.

References

- 1.Omonzejele P. Obligation of nonmaleficence: moral dilemma in physician-patient relationship. JMBR. 2005;4:22–30. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henderson GE, Churchill LR, Davis AM, et al. Clinical trials and medical care: defining the therapeutic misconception. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hebert RS, Elasy TA, Canter JA. The Oslerian triple threat: an endangered species? A survey of department of medicine chairs. Am J Med. 2000;109:346–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00533-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sande M, Ronald A. The Academic Alliance for AIDS Care and Prevention in Africa. Acad Med. 2008;83:180–4. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318160b5cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mullan F. Responding to the global HIV/AIDS crisis: a Peace Corps for health. JAMA. 2007;297:744–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.7.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine . Healers abroad: responding to the human resource crisis in HIV/AIDS. National Academies Press; Washington DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osler W, McGill University . Study of dying. Bibliotheca Osleriana; Montreal: 1904. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Panosian C, Coates T. The new medical “missionaries”—grooming the next generation of global health workers. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1771–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]