Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease that causes the body to destroy insulin-producing β-cells in the pancreas. Genetic susceptibility is a major component of the disease pathogenesis. Many of the genes involved in disease susceptibility are major players in coordinating immune response. For example, the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II genes, known as human leukocyte antigens (HLAs) in humans, are the most prominent susceptibility genes (1). Besides genetic factors, there is strong evidence suggesting that environment contributes to the development of type 1 diabetes (2). The most striking example being that the incidence of diabetes differs in monozygotic twins (3). Other examples include the geographic distribution of type 1 diabetes and immigrants exhibiting the incidence prevalent in their new country of residence (4). Even if it may be a difficult task, efforts to find environmental causes are necessary as part of a potential future prevention program (5).

In humans, the accumulation of islet antibodies with differential specificities for β-cell proteins, in combination with genotyping for susceptibility alleles, can predict the risk to develop clinical diabetes. However, we are still unable to arrest β-cell destruction in pre-diabetic patients, even though a lot of evidence collected from preclinical studies using various therapeutic regimens in different animal models for type 1 diabetes has been successful in preventing type 1 diabetes (6). Some compounds (anti-CD3 antibodies, GAD of 65 kDa [GAD65], Diapep277, and anti-thymocyte globulin [ATG]) that reestablished long-term tolerance in animal models after new-onset type 1 diabetes show promising effects in reducing β-cell decline in phase I and II clinical trials in humans with recently diagnosed type 1 diabetes, but none of them was able to cure the disease (7). We have to ask, what are the current hurdles that make translation from animal models to humans so difficult and how can we build better preclinical models to facilitate the transition from bench to bedside?

CURRENT RODENT MODELS FOR TYPE 1 DIABETES

Advantages and difficulties

It is now commonly accepted that animal models are required to investigate the fundamental disease mechanisms leading to type 1 diabetes as well as to evaluate new therapeutic avenues. A major reason is the inability to access the human pancreas and islets directly and document the events taking place during diabetogenesis. Although some more recent efforts will tackle this issue (for example, see the online Network for Pancreatic Organ Donors with Diabetes, www.nPOD.jdrf.org), the need for utilizing animal models will not be circumvented very soon; their relevance to human diabetes has been the focus of many debates and disagreements over the years (8–13). To date, the foremost question is not whether animal models are needed but rather how to best employ them in order to improve our understanding of the human pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes and increase our success rate in the development of therapies. It is important to understand that likely none of the current models will perfectly reproduce the human situation. We should therefore ask, what makes one animal model better suited than another to answer a specific question, teach us about a specific stage of human type 1 diabetes, and evaluate new therapies?

Nonobese diabetic models

The nonobese diabetic (NOD) model has proven to be an important tool for dissecting both central and peripheral tolerance mechanisms that contribute to spontaneous autoimmune diabetes (14,15). This mouse model is unique in the sense that diabetes occurs spontaneously driven by a number of immune defects and alterations that contribute the lack of control for the activation of autoreactive effector T-cells. Among the main lessons we have learned from this mouse model, the following can be highlighted: Undoubtedly, environment plays an important role in the development of type 1 diabetes. Disease penetrance in NOD mice is optimal in specific pathogen–free conditions and decreases drastically in a less clean, conventional environment. This observation together with the fact that human diabetes incidence is increased in industrialized countries lead to the “hygiene hypothesis” (16), which proposes that a lack of early childhood exposure to infectious agents increases susceptibility to autoimmune and allergic diseases later on in life.

The NOD strain carries multiple autoimmune susceptibility genes that provide a fertile background for several autoimmune syndromes. However, the major contributor to type 1 diabetes susceptibility is the MHC class II molecule itself (I-Ag7). Interestingly, the genetic introduction of alternative MHC genes protects from diabetes but confers susceptibility to alternative autoimmune syndromes (17). Therefore, the MHC locus is paramount for driving the pathogenic process leading to type 1 diabetes and other autoimmune diseases.

More than 200 immune interventions have been described to prevent type 1 diabetes in NOD mice (6). Although few interventions can reverse recent-onset type 1 diabetes (anti-CD3, ATG, combination therapies, Diapep277, and proinsulin DNA vaccine), some are now being tested in humans with some success (i.e., preservation of C-peptide for up to 24 months) (18–20). The discrepancy between the ease of curing rodent diabetes and the difficulty of translating this to cure human type 1 diabetes could be attributed to the fact that rodents are less prone to exhibit symptoms from immunosuppression, the difficulty of translating dosing regimens from mice to humans, the possibility that human β-cells are less able to regenerate or replicate (21), and the fact that mice only live for 2 years, which in the end might equate only 2 human years of life and is actually reflected in the duration of the protective effect in current trials.

We would also like to draw attention to the following issues. First, even though NOD mice are in fact multiple copies of a single individual, under an identical germ-free environment, they will not develop diabetes with the same rate, and nearly 20% of the females and 50% of the males will never develop the disease. Therefore, we should study in depth the animals that do not develop type 1 diabetes and understand the reasons for such a discrepancy in order to shed new lights on mechanisms driving type 1 diabetes pathogenesis. Second, the NOD model alone has been ineffective to predict efficacy of preventive therapies when translated into humans. One should consider using differential models that highlight different pathways to type 1 diabetes pathogenesis when testing future treatments. For instance, development of antigen-based therapies will certainly profit from the use of novel humanized MHC class II mouse models (22–25). Last, in order to select the most potent therapeutics to be tested in humans, one has to test each treatment under the most stringent conditions (for instance after and not before onset of hyperglycemia). In addition, we would benefit from routinely providing separate dose/efficacy measurements in correlation with the different blood glucose values at the onset of treatment.

Knockout models

The knockout models of spontaneous type 1 diabetes or other autoimmune defects (mice in which one or more genes have been turned off through a gene knockout) may identify a new set(s) of genes/mutations in the development of human type 1 diabetes. However, autoimmunity resulting from specific known mutations or pathway defects in mouse models might not always be relevant for the human situation. Thus, each pathway identified by these models needs to be specifically assessed in humans in order to appropriately validate such disease phenotypes.

Humanized murine models

The humanized murine models (mice carrying functioning human genes), generated by introduction of MHC, T-cell receptor (TCR), and costimulatory genes from humans into NOD/severe combined immunodeficiency disease (NOD/SCID) mice, constitute a great value for better understanding certain unexplored aspects of the human condition. Such models are well-suited 1) mechanistically, to address the questions of which T-cells and antigens drive the diabetogenic response, and 2) therapeutically, to test the efficacy of antigen-specific interventions and induction of regulatory versus effector T-cell responses in the context of humanized MHC. But one must stress that these mice are only partially humanized. As a result, recapitulation of in vivo properties (i.e., cell expansion, homing, and interaction with matrix and tissues) might be impacted by biased interactions between human and murine molecules, leading to erroneous interpretations.

Transgenic models

The first transgenic mouse models for type 1 diabetes were generated almost 20 years ago. In these models, the mouse genome is genetically engineered to express proteins from diabetes-unrelated agents (such as ovalbumin, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus [LCMV], influenza, etc.) in the pancreatic β-cells under the control of insulin promoters (26–28). These models, where the initiating antigen is well defined, are very valuable for testing different modalities of antigen-specific interventions. Antigen-derived therapies are advantageous because they avoid general immunosuppression by acting site-specific within the pancreatic tissue and can dampen multiple autoaggressive responses by a phenomenon called infectious tolerance (29). In particular, they offer the opportunity to test interventions on diverse genetic backgrounds, which may be important for designing and analyzing future antigen-based clinical trials, where responsiveness to immunotherapy might vary from patient to patient, harboring various MHC molecules.

BioBreeding diabetes-prone models

The BioBreeding diabetes-prone (BB-DP) rat constitutes a unique model for studying type 1 diabetes. BB-DP rats express and share susceptibility genes with human type 1 diabetes (30,31) and develop spontaneous diabetes at about 12 weeks of age. These characteristics make the BB-DP rats a good experimental model to investigate type 1 diabetes pathogenesis and test novel therapeutics, as it allows the manipulation of a larger animal model from a different genus (rat vs. mouse).

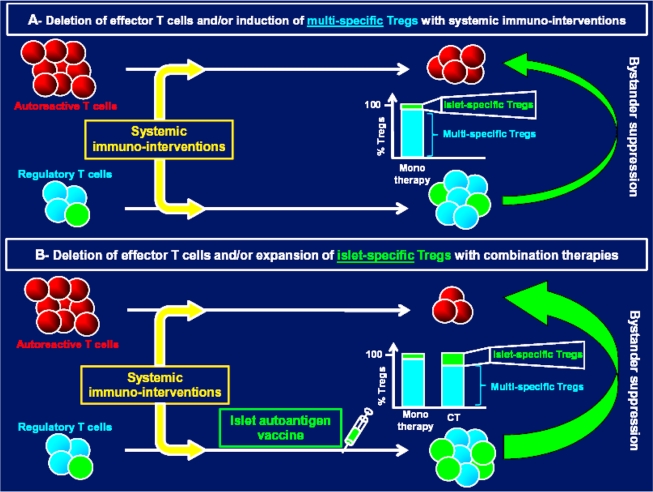

FROM PRECLINICAL STUDIES TO HUMAN TRIALS

Many prevention and intervention trials have been conducted to evaluate the potential of various compounds to induce tolerance in type 1 diabetes (Table 1). Prevention trials, aiming at treating susceptible individuals before onset, have tested nicotinamide or various forms and routes of administration of human insulin (32–35). Intervention trials have attempted to preserve β-cell function in newly diagnosed type 1 diabetic patients by using systemic immune modulators (such as cyclosporine A, non-Fc binding anti-CD3, anti-CD20, DiaPep277, etc.) or antigen-specific therapies (insulin, GAD65, and altered peptide ligand derived from the insulin peptide B9-23) (18–20,36–42). So far, only a handful of trials using the drugs anti-CD3, Diapep277, anti-CD20, or GAD65 have showed efficacy in preserving C-peptide (from 12 to 30 months posttreatment) in individuals with recently diagnosed type 1 diabetes, even though they were unable to cure the disease. In the best case scenario, a preservation of C-peptide levels over a 24-month period was reported in the majority of treated patients. However, to date, none of the 87 patients enrolled in these “successful” trials has achieved euglycemia. Overall, one can conclude that systemic immune modulators without antigen-specific induction of tolerance or active immune regulation have showed the most robust yet temporarily limited preservation of β-cell function. Only one antigen-based immune intervention, the Diamyd GAD65 trial, has been shown to preserve residual insulin secretion in patients with recent-onset type 1 diabetes (20), and the longevity of the effect is still under follow-up observation. The reason for the fact that preservation of C-peptide is only limited in duration is likely the recurrence of the autoimmune response mediated by autoaggressive memory cells, which has been recently well documented in clinical trials of islet transplantation (43,44). Eliminating all autoimmune memory via immunosuppression alone is very difficult to achieve; this is illustrated by the observation that even after autologous nonmyeoloablative bone marrow transplantation (45), insulin independence is limited in duration. In our opinion, it will be instrumental to secure long-term tolerance and control of autoreactive memory T-cells by inducing islet antigen–specific immune regulation, which can likely be long lived and is inducible without systemic adverse effects. The Diamyd GAD65 trial (see above) is possibly the first step in this direction, although induction of GAD65-specific T regulatory cells (Tregs) will still have to be clearly shown. Present data indicate that this might have been the case, as elevated T helper 2 (Th2) and interleukin (IL)-10 cytokine levels were found in patients immunized with GAD65 (20). Ultimately, combination therapies that involve a short-term course of an immunosuppressive drug such as anti-CD3 or anti-CD20 to eliminate autoreactive memory T-cells followed by an islet antigen–specific therapy to induce Tregs that could maintain long-term tolerance might be the best solution (Fig. 1). Our experimental data indicate that this is indeed possible (46).

Table 1.

Efficacy of various treatments for type 1 diabetes tested in animal models and/or in human clinical trials

| Treatment | Efficacy in animal models | Clinical trial | Time of administration | Efficacy observed | Side effects reported in humans | Possible reasons for discrepancies or similarities between animal models and humans | Ref.(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monotherapies (antigen-specific) | |||||||

| Human insulin (parenteral) | 1) Human insulin unable to prevent/reverse T1D in NOD mice (porcine isoform more effective) 2) Only very high doses (5 mg/oral gavage twice a week for 7 weeks) prevented T1D in RIP-LCMV mice (porcine isoform more potent) (60). | Diabetes Prevention Trial–Type 1 (DPT-1) | Prevention trial | No effect | Well tolerated | 32, 34, 60 | |

| Human insulin (nasal) | Type 1 Diabetes Prediction and Prevention (DIPP) study | Prevention trial | No effect | Minimal hypoglycemia, some transient nasal stinging or irritation | 35 | ||

| Human insulin (nasal) | Australian phase I nasal insulin trial (INIT I) | Prevention trial | No accelerate loss of β-cell function in individuals at risk for T1D and immune changes consistent with mucosal tolerance to insulin detected. | Well tolerated | Possible that too frequent dosing lead to deletion of adaptive Tregs. | 58 | |

| Human insulin (nasal) | Australian phase II nasal insulin trial (INIT II) | Prevention trial | Recruiting | ||||

| Human insulin B-chain in IFA | Can prevent diabetes development in NOD mice. | Funded by the Immune Tolerance Network | In new-onset diabetes (within a month of diagnosis) | Clinical trial still recruiting | NA | Optimal timing and dosage and route of administration must be established. | 87–89 |

| Human insulin (oral) | IMDIAB VII | After new onset | No effect | Well tolerated | 1) Antigen species (human vs. porcine) drives efficacy in animal models. In humans? 2) Oral dosage lower in humans than mice 3) Optimal timing and dosage and route of administration must be established. | 36 | |

| Altered peptide ligand insulin B9-23 | |||||||

| (A16,19) [NBI-6024] | 1) Subcutaneous injections of NBI-6024 in acqueous solution to NOD mice prevented diabetes onset. 2) Subcutaneous administration of NBI-6024 emulsified in IFA after new-onset disease (blood glucose values >200 mg/dl) substantially diminished diabetes incidence. | NBI-6024 (Neurocrine) | After new onset | 1) Phase I clinical study strongly suggested NBI-6024 treatment shifted the Th1 pathogenic responses in recent-onset T1D patients to a protective Th2 regulatory phenotype. 2) Phase II multi-dose trial was ineffective (data not published). | Well tolerated | Optimal timing and dosage and route of administration must be correctly scaled from mouse to human. | 41, 90 |

| Plasmid encoding human proinsulin | As efficacious as anti-CD3 mAb in reversing new-onset T1D in NOD mice. | BHT-3021 (BayHill Therapeutics) | After new onset | Phase I/II clinical trial, drug reduced anti-insulin antibody titers in treated vs. placebo control (http://www.bayhilltx.com/T1D.html). | BHT-3021 demonstrated safety and tolerability, with no increase in adverse events among first nine patients relative to placebo. | Vast majority of MHC class II epitopes described (91) encompass amino acids within leaders and C-peptide domains (the opposite for MHC class I epitopes). Using a proinsulin instead may tip balance of MHC class I/class II epitopes presented in vivo towards CD4+ T-cell compartment and ameliorate therapeutic outcomes in animal models and humans. | 91 |

| Human GAD65 | 1) Prevention of diabetes in NOD mice. 2) Protection from diabetes when administered i.v. at 12 weeks old in NOD (just before onset). 3) Synergy between human GAD65 DNA vaccine and anti-CD3 in new-onset diabetes in RIP-LCMV but not NOD models. 4) 200 μg/animal i.v. failed to prevent diabetes in BB-DP rats. | GAD65 (Diamyd) | After new onset | 1) 124-week positive effect in LADA patients observed with only one of five doses tested. 2) No significant effect on change in fasting C-peptide level after 15 months. 3) Fasting C-peptide levels declined from baseline significantly less over 30 months in GAD-alum group than in placebo group. 4) No protective effect seen in patients treated 6 months or more after diabetes diagnosis. | Well tolerated | 1) Immunization with GAD65 from various antigen species (human, murine, or porcine) results in similar efficacy. 2) Full-length human GAD65 treatment alone not able to reverse diabetes after onset in animal models. Timing of treatment appears crucial. | 20, 92–96 |

| Hsp60 immunodominant peptide p277 (residues 437–460) | 1) Prevention of diabetes in NOD mice, even though a study shows contradictory data (97). 2) No synergy between p277 and anti-CD3 in new-onset diabetes in NOD and RIP-LCMV models. 3) Short-term neonatal feeding with p277 in early life, combined with hydrolyzed casein diet, protects against T1D in BB-DP rats. | DiaPep277 | After new onset | 1) 18-month greater preservation of β-cell function in Diapep277-treated than in placebo group. 2) Follow-up clinical trials showed modest or no efficacy (98). 3) Phase III clinical trials recruiting in newly diagnosed T1D (clinicaltrials.gov ID: NCT00615264 and NCT00644501). | Well tolerated | Never tested at the pre-diabetic stage in humans. | 37, 46, 73, 97, 99 |

| Islet autoantigen–derived peptides eluted from human HLA class II molecules as vaccines for the immunotherapy of T1D | Concept of MHC class II–eluted peptides never applied to mouse models, but many studies show immunizations with various peptides can halt disease progression when administered in the pre-diabetic phase. | Funded by the Diabetes Vaccine Development Centre (University of Melbourne, Australia) and the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation | Longstanding and newly diagnosed diabetes | Clinical trial still recruiting | NA | Treatment with peptidic vaccines without adjuvant disappointing in animal models when administered after new-onset diabetes (as proposed in this trial). Use of MHC class II peptide binders could improve clinical efficacy. | 63–65 |

| Monotherapies (systemic immunotherapy) | |||||||

| Cyclosporin A | Canadian/European CsA trial | After new onset | Preservation of C-peptide only during drug administration | Significant variations in systolic blood pressure, hemoglobin levels, and serum potassium and creatinine levels during drug administration | 40 | ||

| Nicotinamide | 1) Prevention of diabetes in NOD mice. 2) High dose failed to prevent diabetes in BB-DP rats. 3) Acceleration of diabetes development in obese diabetic (db/db) mice (T2D model). | European Nicotinamide Diabetes Intervention Trial (ENDIT) and Deutsche Nicotinamide Intervention Study (DENIS) | Prevention trial | No effect | Well tolerated | 1) Dosage (mg/kg) 50–100 times lower in humans. 2) Efficacy only observed in one animal model. 3) Pleiotropic activities resulting in differential efficacies. | 33, 39, 100–102 |

| Nicotinamide | 1) Prevention of diabetes in NOD mice. 2) High dose failed to prevent diabetes in BB-DP rats. 3) Acceleration of diabetes development in obese diabetic (db/db) mice (T2D model). | Deutsche Nicotinamide Intervention Study (DENIS) | Prevention trial | No effect | Decreased first-phase insulin secretion in response to intravenous glucose | 1) Dosage (mg/kg) 50–100 times lower in humans. 2) Efficacy only observed in one animal model. 3) Pleiotropic activities resulting in differential efficacies. | 33, 39, 100–102 |

| Anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody | Short-term treatment after new-onset diabetes permanently reversed disease in NOD and RIP-LCMV animal models. | hOKT3g1(Ala-Ala)-mutated human anti-CD3: Non-Fc binding anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (American trial) | After new onset | 24-month positive effect on C-peptide levels (transient remission) | Moderate fever, anemia, headache, and rash due to spongiosis (upon drug administration) | 1) Earlier administration of the drug in new-onset patients might improve efficacy. 2) Second injection of tanti-CD3 1 year after first administration could sustain efficacy, but adverse effects could be a problem. | 18, 19, 103, 104 |

| Anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody | Short-term treatment after new-onset diabetes permanently reversed the disease in NOD and RIP-LCMV animal models. | ChAglyCD3-aglycosylated human anti-CD3 (TRX4): Non-Fc binding anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (European trial) | After new onset | 18-month positive effect in patients with highest C-peptide levels at entry (≥50th percentile) | Moderate fever, anemia, headache, rash, and EBV reactivation (upon drug administration) | 1) Earlier administration of the drug in new-onset patients might improve efficacy. 2) Second injection of tanti-CD3 1 year after first administration could sustain efficacy, but adverse effects could be a problem. | 18, 19, 103, 104 |

| Anti-CD20 | Prevent and reverse T1D in NOD mice. | Rituximab in T1D | After new onset | NA (http://www.diabetestrialnet.org) | NA (ongoing) | Involvement of B-cells in pathogenesis of T1D controversial in mice and humans. If involvement different between mouse models and humans, it will result in differential efficacy of anti-CD20 antibody. | 105, 106 |

| Human recombinant IL-1Ra (IL-1 receptor antagonist) | Improve survival of islet transplants in NOD mice. | Anakinra in T1D | Newly diagnosed T1D within 1 week of diagnosis | NA. Phase I/II recruiting (http://clinicaltrial.gov/ct2/show/NCT00645840?term=anakinra&rank=4) | NA | 1) Efficacy not proven after administration in newly diagnosed mouse models. 2) May affect expansion of effector T-cells but not expansion/activation of Tregs to maintain long-term tolerance. | 107–110 |

| Anti-CD52 | Favor the induction of CD4+ regulatory T-cells in mice. | 1) clinicaltrials.gov ID: NCT00214214 2) Campath-1H in T1D | New-onset diabetes | Phase I clinical trial withdrawn prior to recruitment | NA | NA | 111, 112 |

| TNF | Selectively kill autoreactive T-cells in mouse models for T1D. | 1) clinicaltrials.gov ID: NCT00607230. 2) Administration of 2 doses of Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) to induce systemic TNF expression | Intervention trial | 1) Phase I clinical trial currently recruiting. 2) Previous clinical trial using single BCG dose ineffective (113). | NA | 1) Similar mechanism of action (elimination of autoreactive T-cells) in mice and human peripheral blood. 2) Early but not late TNF expression by the β-cells during pathogenesis of T1D can accelerate diabetes in animal models. Timing is crucial to avoid unacceptable side-effects. | 113–119 |

| Byetta, exenatide or exendin-4 | Only modest efficacy when administered before onset in NOD mice. | AC2993 (synthetic exenatide), clinicaltrials.gov ID: NCT00064714 | Intervention trial | Phase II clinical trial completed | Well tolerated | From animal models, exenatide needs to be administered in combination with immune modulators to show efficacy. | 120 |

| Combination therapies IL2 (in combination with sirolimus) | Prevented spontaneous autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice. | clinicaltrials.gov ID: NCT00525889 | Intervention trial | Phase I clinical trial currently recruiting | NA | Optimal timing and dosage must be correctly translated from mouse to human. | 121 |

| Anti-CD3 and nasal or oral insulin | Short-term treatment showed synergy in treating recent-onset T1D in NOD and RIP-LCMV mouse models. | NA | Intervention trial after recent onset | Planned | NA | Optimal timing and dosage must be correctly translated from mouse to human. | 46 |

| Anti-CD3 and exenatide | Short-term treatment showed synergy in treating recent-onset T1D in NOD mice. | NA | Intervention and prevention trials | Planned | NA | Timing will be crucial: Treatment must be administered early enough to enable β-cell stimulation/growth from exenatide but not too early, since anti-CD3 not effective in a preventive setting in NOD mice. | 54 |

| Epidermal growth factor (EGF) and gastrin | Restores normoglycemia in diabetic NOD mice when administered very early after onset (blood glucose values >200 mg/dl). | Phase II trial (E1-INT) | Intervention trial | Daytime insulin usage reduced 35–75% in 3 of 4 T1D patients. Reductions of daytime insulin usage evident after the 28-day treatment period and peak 1–2 months post-treatment, during which patients have maintained stable blood glucose control as measured by A1C. | Well tolerated, principal adverse events were nausea and headache | Treatment must be administered early enough after recent-onset to enable β-cell stimulation/growth. | 122–124 |

| Exenatide and gastrin | Restores normoglycemia in diabetic NOD mice when administered very early after onset (blood glucose values >180 mg/dl). | Phase II trial | Intervention trial | Planned | NA | Treatment must be administered early enough after recent-onset to enable β-cell stimulation/growth. | 125, 126 |

EBV, Epstein Barr virus; Hsp60, heat-shock protein-60; IFA, incomplete Freund's adjuvant; LADA, latent autoimmune diabetes in adults; NA, not available; T1D, type 1 diabetes; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

Figure 1.

Combination of systemic and antigen (islet)-specific immunotherapies to expand/invigorate islet-specific regulatory T-cells (Tregs) for treating type 1 diabetes. A: Systematic immunointerventions can be used after new-onset type 1 diabetes to delete/block autoreactive T-cells and/or expand multispecific Tregs (among these Tregs a small proportion will recognize islet-autoantigen and mediate bystander suppression). B: Combining systemic and islet-specific immunotherapies (CT) has already proven to be effective in expanding/invigorating a higher number of islet-specific Tregs than monotherapies given alone (46), which in return increases treatment efficacy.

In view of the completed clinical trials, positive outcomes were solely observed when treatments were administered after recent-onset of type 1 diabetes. One might find this unusual, since, based on observations in animal models, prevention is much easier to achieve than intervention. However, several reasons account for this: First, safety, as well as economical considerations, makes it more suitable to test new immune-based interventions first in individuals with recent-onset type 1 diabetes or already established disease. Second, we still lack suitable biomarkers or other tools (i.e., computer-based models) that would allow us to choose the correct dose and administration schedule for immunotherapies (especially islet antigen–based ones). Indeed, we now possess powerful tools to predict type 1 diabetes in susceptible individuals based on measurements of serum autoantibodies (aAbs) (anti-insulin, anti-GAD65, and anti–IA-2 aAbs) and HLA background. However, reliable biomarkers to predict therapeutic success following the intervention are still lacking. The following issues need to be better understood to optimize the design of future prevention trials; in the last two sections of this article, we offer some future strategies to tackle these issues:

-

Oral administration of human insulin has been shown to induce IL-4–secreting CD4+ T-cells with suppressive activities in NOD mice when co-injected with diabetogenic cells into recipients (47,48). Other studies described that a similar treatment regimen was more effective when administered early in NOD life (starting at 3–4 weeks of age) (49,50). Efficacy was further increased when NOD neonates were fed with human insulin (49). Protection from diabetes at a late stage in NOD mice (after 12 weeks of age) was ameliorated when human insulin was administered subcutaneously (51). Consequently, many variables may influence the efficacy of human insulin (or other autoantigen [aAg]) therapy, including the dosage, frequency of administration, and stage of the disease. As a result, more effort should be put into understanding the effect of these variables on tolerance and Treg induction in order to correctly scale-up such preventions from mice to humans and define the optimal moment to detect Tregs in peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

It is worth noting that the amino acid sequence of islet aAgs may also affect the efficacy to promote tolerance in vivo. As an example, oral porcine insulin B-chain was able to significantly better prevent diabetes in both NOD and rat insulin promoter (RIP)-LCMV mouse models, while oral human insulin B-chain was less effective (52). Therefore, small structural differences in the primary sequence (here only one amino acid difference) can produce dramatic differences in the clinical outcome. In this context, it is important to notice that only human oral insulin has been tested thus far in clinical trials (Table 1).

The degree of the β-cell function at trial entry appeared to be crucial for a positive response in intervention trials (19,20). Greater β-cell function (or higher C-peptide) at onset of treatment appears to result in better preservation of C-peptide after therapy. Consequently, clinical intervention trials need to be started very early after diagnosis for optimal outcome, and patients must be stratified according to C-peptide levels.

Last, we would argue that a monotherapy will likely not reach sufficient efficacy or safety to maintain permanent tolerance. The pathogenetic heterogeneities observed among patients (see www.nPOD.jdrf.org) might not be conducive for the development of a monotherapeutic agent that will be efficacious and safe for all diabetic patients. To accelerate progress, we propose to combine compounds that will expand islet-specific Tregs, curb β-cell destructive effector cells, and help regenerate the β-cell function to halt C-peptide decline (53). Along these lines, several clinical trials are already planned (Table 1). Our team has previously shown that combining systemic anti-CD3 with islet-aAg immunizations resulted in a synergy that specifically expanded aAg-specific Tregs that were recruited to the site of inflammation in the pancreatic lymph nodes, where they attenuated the autoimmune aggression by effector T-cells (46). In addition, clinical signs of diabetes often appear when a significant percentage of β-cells (15–20%) still remains. Consequently, combination with further drugs is urgently needed for promoting regeneration/invigoration of the residual β-cells in order to restore normoglycemia in newly diagnosed patients. So far, glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and its long-acting analog (exendin-4, also known as exenatide), or a mixture of GLP-1 and gastrin, were the most promising drugs for stimulating β-cell expansion in vivo. As a result, clinical trials are under way to test their efficacy in a mono- or a combination therapy with anti-CD3 based on preclinical data (54).

IN SILICO BIOSIMULATIONS TO SPEED UP CLINICAL TRANSLATION FROM BENCH TO BEDSIDE

Although a variety of immune interventions have been capable of delaying or treating type 1 diabetes in animal models (6), few of them have showed some efficacy when translated into the clinic (Fig. 1). Induction of long-term aAg-specific tolerance remains particularly difficult. In many cases the activation of adaptive aAg-specific Tregs is dependent upon several factors such as the aAg itself as well as the dose, timing, and appropriate route of administration. Defining an optimal regimen experimentally is a daunting task and requires many years of “wet-lab” study in animal models, which must then be translated in scale to humans. Therefore, to guide research for the development and mechanistic evaluation of immune-based therapies in type 1 diabetes, one must consider the use of in silico biosimulations. The major advantage of this approach relies on its ability to generate and analyze a large number of treatment scenarios in a short period of time, thus accelerating the generation of new hypothesizes while lowering the research costs. One major hurdle to overcome remains the development of virtual models closely mimicking the animal or human disease, particularly when the disease pathogenesis is still not fully understood in real life.

However, in silico modeling has already identified testable explanations that could account for the failure or success of type 1 diabetes therapies tested in NOD mice (55,56). Therefore, a close collaboration between “wet-lab” and “virtual-lab” investigators may enable more rational experimental design and accelerate the path from basic research to clinical trials. As an example, our laboratory recently collaborated with Entelos, Inc., a life sciences company that developed the type 1 diabetes PhysioLab platform, a predictive in silico model of type 1 diabetes progression in the NOD mouse (57).

Entelos generated a variety of virtual NOD mice to investigate the possible mechanisms underlying the efficacy of intranasal insulin B:9-23 peptide therapy and to evaluate the impact of dosage, frequency of administration, and age at treatment initiation on the therapeutic outcome. In silico modeling predicted that high-frequency immunizations inhibited tolerance induction by deleting Tregs before they can expand sufficiently to provide therapeutic benefit. In addition, treatment was predicted to be most effective if started at an earlier age, relying on increased Tregs and IL-10 levels in the islet. These predictions were confirmed in vivo, established an optimized immunization frequency, and mapped the time of induction of Tregs that require IL-10 as critical parameters for translating mucosal tolerance induction strategies such as administration of nasal insulin to humans (G. Fousteri and M.v.H., unpublished data). One can imagine that similar predictive simulations could guide human trial design and define optimal dosing regimens and the optimal time for testing for induced T-cells (as biomarkers).

DEVELOPING (IMMUNOLOGICAL) BIOMARKERS FOR CLINICAL TRIALS

Once a clinical trial has been initiated, biomarkers are required to monitor and/or predict treatment efficacy. This helps to rule out wrong dosages and regimens and can save substantial costs (especially in prevention trials) because negative outcomes can be anticipated long before clinical development of type 1 diabetes. While it is relatively easy to follow the physiological effect of a particular treatment by measuring C-peptide levels (reflecting β-cell function) in the peripheral blood, no reliable immunological biomarker to date successfully predicts therapeutic outcomes. The lack of suitable immunological biomarkers measurable in peripheral blood that track therapeutic success in both animal models and humans hampered the finding of an optimal dose regimen for improving effectiveness for many interventions, e.g., oral or nasal insulin administration and subcutaneous peptide or DNA vaccine interventions (34–36,58–62). Therefore, much effort should now be put into the development of such peripheral biomarkers (63–65). These studies should also be conducted in mice, where measurements in peripheral blood are frequently avoided because of easy access to lymphoid organs or the pancreas itself, which facilitates the immediate immunological readout. However, the discovery of peripheral biomarkers in animal models could accelerate the translatability to the human situation since lymphoid organs and the pancreatic islets are not accessible. The following options should be considered.

Cytokine(s) measurement

Development of type 1 diabetes is usually accompanied by a shift in cytokine expression from Th2 to Th1 cytokines due to a persistent inflammation in the pancreas (66). Therefore, tilting the balance toward Th2 expression might be a sign of clinical efficacy. Such an immune deviation can be measured 1) in the serum of treated patients, as observed in the anti-CD3 hOKT3gamma1(Ala-Ala) clinical trial (Table 1) (67), or 2) after in vitro (antigen-specific) stimulation of peripheral T-cells secreting IL-10, as evidenced upon antigen-specific therapy using an HLA-DR4–restricted peptide epitope of proinsulin (C19-A3) (62). Moreover, the presence of islet antigen–specific T-cells expressing IL-10 can discriminate between healthy and diabetic individuals (63) and predict glycemic control in type 1 diabetic patients at diagnosis (68).

Anti-islet autoantibodies

The presence of multiple aAbs (anti-insulin, anti-GAD65, and anti-IA2) has the highest positive predictive value for type 1 diabetes (69). However, their involvement in human type 1 diabetes pathogenesis remains unclear (70), but they could facilitate antigen presentation (71). Consequently, variation(s) in serum aAb levels could be more relevant as a marker for efficacy in prevention rather than intervention trials (72). Thus far none of the intervention trials showing positive outcomes (19,20,38) or islet transplantation trials under immunosuppressive regimen have provided direct evidence for the relevance of aAbs in predicting clinical efficacy (18,20,73).

Tracking autoreactive T-cells ex vivo

In a clinical setting, one could envision tracking either autoaggressive islet-specific T-cells or (antigen-induced) Tregs upon treatment. To do so, two widely used protocols exist. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT) assay that informs on the antigen specificity and number, as well as the cytokine expressed by CD4+ or CD8+ T-cells. Other techniques, such as cell surface staining using recombinant MHC/HLA class I or II tetramers followed flow cytometry analysis, enumerate the number of antigen (epitope)-specific CD8+ or CD4+ T-cells, respectively. While the ELISPOT assays can detect even low numbers of antigen-specific T-cells, the use of tetramer staining has been hampered by difficulties in developing functional MHC/HLA class II tetramers with binding avidity high enough to track CD4+ T-cells. However, both techniques have shown great progress (74–78), and it should be possible in the future to evaluate fluctuations in the number of antigen-specific T-cells in longitudinal prospective studies following immune interventions. Detection of antigen-induced Tregs (62,73) or autoaggressive islet-specific T-cells (79,80) has been reported. Nevertheless, it is still possible that T-cell receptor usage is heterogeneous even within a given individual, which would strongly reduce the feasibility of tracking autoaggressive T cells with one or few specificities as biomarkers for disease progression or therapeutic success.

In vivo imaging

Measuring β-cell mass by in vivo imaging has proved to be challenging over the years. However, this approach is vital to directly assess the effect of a treatment on pancreatic β-cells, gain further knowledge of disease kinetics, and move toward a better management of type 1 diabetes. Several technical advances have emerged, such as magnetic resonance imaging, positron emission tomography, or bioluminescence imaging, and have been successfully used to detect murine and rat islets (81–83). Unfortunately, thus far no direct and reliable technique enables the detection and accurate measurement of living β-cells in humans. We would argue that more efforts should be put into developing in vivo imaging of pancreatic β-cell mass for clinical use.

CONCLUSIONS

Realizing immune-based interventions for human type 1 diabetes will be necessary, even if an unlimited source of new islets can be obtained from stem cells or other sources, because autoimmune memory cells will have to be controlled to avoid continued loss of β-cells over time. The key issue that must be tackled is achieving a tolerable balance between immunosuppression and the associated side-effects and long-term tolerance. In our opinion, the likelihood that monotherapies with systemically acting immunomodulators will achieve this is low because, even in the best case scenario, side effects will emerge after 20–30 years, as has been seen with immunosuppressive regimens in transplantation (84). Therefore, adaptive Tregs that recognize β-cell antigens, proliferate in the pancreatic lymph nodes (85,86), and can, at least in multiple animal models, mediate islet-specific immunosuppression should be induced in conjunction with systemic immunomodulatory therapies, for example by immunization with GAD65, (pro)insulin, (pro)insulin peptides, or DNA vaccines. To optimize dosing regimens, in silico modeling approaches could be used together with animal experimentation and reliable biomarkers that can predict successful induction of adaptive Tregs following aAg immunization must be established.

Acknowledgments

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Footnotes

See accompanying article, p. 1769.

References

- 1. Maier LM, Wicker LS: Genetic susceptibility to type 1 diabetes. Curr Opin Immunol 2005;17:601–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lammi N, Karvonen M, Tuomilehto J: Do microbes have a causal role in type 1 diabetes? Med Sci Monit 2005;11:RA63–RA69 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Olmos P, A'Hern R, Heaton DA, Millward BA, Risley D, Pyke DA, Leslie RD: The significance of the concordance rate for type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes in identical twins. Diabetologia 1988;31:747–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Daneman D: Type 1 diabetes. Lancet 2006;367:847–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) Study. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008;1150:1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shoda LK, Young DL, Ramanujan S, Whiting CC, Atkinson MA, Bluestone JA, Eisenbarth GS, Mathis D, Rossini AA, Campbell SE, Kahn R, Kreuwel HT: A comprehensive review of interventions in the NOD mouse and implications for translation. Immunity 2005;23:115–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Staeva-Vieira T, Peakman M, von Herrath M: Translational mini-review series on type 1 diabetes: immune-based therapeutic approaches for type 1 diabetes. Clin Exp Immunol 2007;148:17–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. New genetic and metabolic insights into animal models of diabetes: proceedings of the 9th International Workshop on Lessons from Animal Diabetes, 17–21 June 2003, Bar Harbor, Maine. Exp Diabesity Res 2003;4:133–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Leiter EH, von Herrath M: Animal models have little to teach us about type 1 diabetes. 2. In opposition to this proposal. Diabetologia 2004;47:1657–1660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liu E, Yu L, Moriyama H, Eisenbarth GS: Animal models of insulin-dependent diabetes. Methods Mol Med 2004;102:195–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rabinovitch A: Animal models of type 1 diabetes are relevant to human IDDM–use caution. Diabete Metab Rev 1998;14:189–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Roep BO, Atkinson M: Animal models have little to teach us about type 1 diabetes. 1. In support of this proposal. Diabetologia 2004;47:1650–1656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Roep BO, Atkinson M, von Herrath M: Satisfaction (not) guaranteed: re-evaluating the use of animal models of type 1 diabetes. Nat Rev Immunol 2004;4:989–997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Anderson MS, Bluestone JA: The NOD mouse: a model of immune dysregulation. Annu Rev Immunol 2005;23:447–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Giarratana N, Penna G, Adorini L: Animal models of spontaneous autoimmune disease: type 1 diabetes in the nonobese diabetic mouse. Methods Mol Biol 2007;380:285–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bach JF: Infections and autoimmune diseases. J Autoimmun 2005;25(Suppl.):74–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cihakova D, Sharma RB, Fairweather D, Afanasyeva M, Rose NR: Animal models for autoimmune myocarditis and autoimmune thyroiditis. Methods Mol Med 2004;102:175–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Herold KC, Gitelman SE, Masharani U, Hagopian W, Bisikirska B, Donaldson D, Rother K, Diamond B, Harlan DM, Bluestone JA: A single course of anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody hOKT3{gamma}1 (Ala-Ala) results in improvement in C-peptide responses and clinical parameters for at least 2 years after onset of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2005;54:1763–1769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Keymeulen B, Vandemeulebroucke E, Ziegler AG, Mathieu C, Kaufman L, Hale G, Gorus F, Goldman M, Walter M, Candon S, Schandene L, Crenier L, De Block C, Seigneurin JM, De Pauw P, Pierard D, Weets I, Rebello P, Bird P, Berrie E, Frewin M, Waldmann H, Bach JF, Pipeleers D, Chatenoud L: Insulin needs after CD3-antibody therapy in new-onset type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2598–2608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ludvigsson J, Faresjö M, Hjorth M, Axelsson S, Chéramy M, Pihl M, Vaarala O, Forsander G, Ivarsson S, Johansson C, Lindh A, Nilsson NO, Aman J, Ortqvist E, Zerhouni P, Casas R: GAD treatment and insulin secretion in recent-onset type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1909–1920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Butler PC, Meier JJ, Butler AE, Bhushan A: The replication of beta cells in normal physiology, in disease and for therapy. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 2007;3:758–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Serreze DV, Marron MP, Dilorenzo TP: “Humanized” HLA transgenic NOD mice to identify pancreatic beta cell autoantigens of potential clinical relevance to type 1 diabetes. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2007;1103:103–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shultz LD, Ishikawa F, Greiner DL: Humanized mice in translational biomedical research. Nat Rev Immunol 2007;7:118–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shultz LD, Pearson T, King M, Giassi L, Carney L, Gott B, Lyons B, Rossini AA, Greiner DL: Humanized NOD/LtSz-scid IL2 receptor common gamma chain knockout mice in diabetes research. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2007;1103:77–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Takaki T, Marron MP, Mathews CE, Guttmann ST, Bottino R, Trucco M, DiLorenzo TP, Serreze DV: HLA-A*0201-restricted T cells from humanized NOD mice recognize autoantigens of potential clinical relevance to type 1 diabetes. J Immunol 2006;176:3257–3265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Oldstone MB, Nerenberg M, Southern P, Price J, Lewicki H: Virus infection triggers insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in a transgenic model: role of anti-self (virus) immune response. Cell 1991;65:319–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ohashi PS, Oehen S, Buerki K, Pircher H, Ohashi CT, Odermatt B, Malissen B, Zinkernagel RM, Hengartner H: Ablation of “tolerance” and induction of diabetes by virus infection in viral antigen transgenic mice. Cell 1991;65:305–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lo D, Freedman J, Hesse S, Palmiter RD, Brinster RL, Sherman LA: Peripheral tolerance to an islet cell-specific hemagglutinin transgene affects both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Eur J Immunol 1992;22:1013–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cobbold S, Waldmann H: Infectious tolerance. Curr Opin Immunol 1998;10:518–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wallis RH, Wang K, Marandi L, Hsieh E, Ning T, Chao GY, Sarmiento J, Paterson AD, Poussier P: Type 1 diabetes in the BB rat: a polygenic disease. Diabetes 2009;58:1007–1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mordes JP, Bortell R, Blankenhorn EP, Rossini AA, Greiner DL: Rat models of type 1 diabetes: genetics, environment, and autoimmunity. ILAR J 2004;45:278–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Effects of insulin in relatives of patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1685–1691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gale EA, Bingley PJ, Emmett CL, Collier T: European Nicotinamide Diabetes Intervention Trial (ENDIT): a randomised controlled trial of intervention before the onset of type 1 diabetes. Lancet 2004;363:925–931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Skyler JS, Krischer JP, Wolfsdorf J, Cowie C, Palmer JP, Greenbaum C, Cuthbertson D, Rafkin-Mervis LE, Chase HP, Leschek E: Effects of oral insulin in relatives of patients with type 1 diabetes: the Diabetes Prevention Trial–Type 1. Diabetes Care 2005;28:1068–1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nanto-Salonen K, Kupila A, Simell S, Siljander H, Salonsaari T, Hekkala A, Korhonen S, Erkkola R, Sipilä JI, Haavisto L, Siltala M, Tuominen J, Hakalax J, Hyöty H, Ilonen J, Veijola R, Simell T, Knip M, Simell O: Nasal insulin to prevent type 1 diabetes in children with HLA genotypes and autoantibodies conferring increased risk of disease: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008;372:1746–1755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pozzilli P, Pitocco D, Visalli N, Cavallo MG, Buzzetti R, Crinò A, Spera S, Suraci C, Multari G, Cervoni M, Manca Bitti ML, Matteoli MC, Marietti G, Ferrazzoli F, Cassone Faldetta MR, Giordano C, Sbriglia M, Sarugeri E, Ghirlanda G: No effect of oral insulin on residual beta-cell function in recent-onset type I diabetes (the IMDIAB VII): IMDIAB Group. Diabetologia 2000;43:1000–1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Raz I, Elias D, Avron A, Tamir M, Metzger M, Cohen IR: Beta-cell function in new-onset type 1 diabetes and immunomodulation with a heat-shock protein peptide (DiaPep277): a randomised, double-blind, phase II trial. Lancet 2001;358:1749–1753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Herold KC, Hagopian W, Auger JA, Poumian-Ruiz E, Taylor L, Donaldson D, Gitelman SE, Harlan DM, Xu D, Zivin RA, Bluestone JA: Anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody in new-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1692–1698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lampeter EF, Klinghammer A, Scherbaum WA, Heinze E, Haastert B, Giani G, Kolb H: The Deutsche Nicotinamide Intervention Study: an attempt to prevent type 1 diabetes. DENIS Group. Diabetes 1998;47:980–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Assan R, Feutren G, Debray-Sachs M, Quiniou-Debrie MC, Laborie C, Thomas G, Chatenoud L, Bach JF: Metabolic and immunological effects of cyclosporin in recently diagnosed type 1 diabetes mellitus. Lancet 1985;1:67–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Alleva DG, Maki RA, Putnam AL, Robinson JM, Kipnes MS, Dandona P, Marks JB, Simmons DL, Greenbaum CJ, Jimenez RG, Conlon PJ, Gottlieb PA: Immunomodulation in type 1 diabetes by NBI-6024, an altered peptide ligand of the insulin B epitope. Scand J Immunol 2006;63:59–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chaillous L, Lefèvre H, Thivolet C, Boitard C, Lahlou N, Atlan-Gepner C, Bouhanick B, Mogenet A, Nicolino M, Carel JC, Lecomte P, Maréchaud R, Bougnères P, Charbonnel B, Saï P: Oral insulin administration and residual beta-cell function in recent-onset type 1 diabetes: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Diabete Insuline Orale group. Lancet 2000;356:545–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Huurman VA, Hilbrands R, Pinkse GG, Gillard P, Duinkerken G, van de Linde P, van der Meer-Prins PM, Versteeg-van der Voort Maarschalk MF, Verbeeck K, Alizadeh BZ, Mathieu C, Gorus FK, Roelen DL, Claas FH, Keymeulen B, Pipeleers DG, Roep BO: Cellular islet autoimmunity associates with clinical outcome of islet cell transplantation. PLoS ONE 2008;3:e2435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Monti P, Scirpoli M, Maffi P, Ghidoli N, De Taddeo F, Bertuzzi F, Piemonti L, Falcone M, Secchi A, Bonifacio E: Islet transplantation in patients with autoimmune diabetes induces homeostatic cytokines that expand autoreactive memory T cells. J Clin Invest 2008;118:1806-1814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Voltarelli JC, Couri CE, Stracieri AB, Oliveira MC, Moraes DA, Pieroni F, Coutinho M, Malmegrim KC, Foss-Freitas MC, Simões BP, Foss MC, Squiers E, Burt RK: Autologous nonmyeloablative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes mellitus. JAMA 2007;297:1568–1576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bresson D, Togher L, Rodrigo E, Chen Y, Bluestone JA, Herold KC, von Herrath M: Anti-CD3 and nasal proinsulin combination therapy enhances remission from recent-onset autoimmune diabetes by inducing Tregs. J Clin Invest 2006;116:1371–1381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bergerot I, Fabien N, Maguer V, Thivolet C: Oral administration of human insulin to NOD mice generates CD4+ T cells that suppress adoptive transfer of diabetes. J Autoimmun 1994;7:655–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ploix C, Bergerot I, Fabien N, Perche S, Moulin V, Thivolet C: Protection against autoimmune diabetes with oral insulin is associated with the presence of IL-4 type 2 T-cells in the pancreas and pancreatic lymph nodes. Diabetes 1998;47:39–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Maron R, Guerau-de-Arellano M, Zhang X, Weiner HL: Oral administration of insulin to neonates suppresses spontaneous and cyclophosphamide induced diabetes in the NOD mouse. J Autoimmun 2001;16:21–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sai P, Rivereau AS: Prevention of diabetes in the nonobese diabetic mouse by oral immunological treatments: comparative efficiency of human insulin and two bacterial antigens, lipopolysacharide from Escherichia coli and glycoprotein extract from Klebsiella pneumoniae. Diabete Metab 1996;22:341–348 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Karounos DG, Bryson JS, Cohen DA: Metabolically inactive insulin analog prevents type I diabetes in prediabetic NOD mice. J Clin Invest 1997;100:1344–1348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Homann D, Dyrberg T, Petersen J, Oldstone MB, von Herrath MG: Insulin in oral immune “tolerance”: a one-amino acid change in the B chain makes the difference. J Immunol 1999;163:1833–1838 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bresson D, von Herrath M: Moving towards efficient therapies in type 1 diabetes: to combine or not to combine? Autoimmun Rev 2007;6:315–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sherry NA, Chen W, Kushner JA, Glandt M, Tang Q, Tsai S, Santamaria P, Bluestone JA, Brillantes AM, Herold KC: Exendin-4 improves reversal of diabetes in NOD mice treated with anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody by enhancing recovery of beta-cells. Endocrinology 2007;148:5136–5144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gadkar KG, Shoda LK, Kreuwel HT, Ramanujan S, Zheng Y, Whiting CC, Young DL: Dosing and timing effects of anti-CD40L therapy: predictions from a mathematical model of type 1 diabetes. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2007;1103:63–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Young DL, Ramanujan S, Kreuwel HT, Whiting CC, Gadkar KG, Shoda LK: Mechanisms mediating anti-CD3 antibody efficacy: insights from a mathematical model of type 1 diabetes. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2006;1079:369–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zheng Y, Kreuwel HT, Young DL, Shoda LK, Ramanujan S, Gadkar KG, Atkinson MA, Whiting CC: The virtual NOD mouse: applying predictive biosimulation to research in type 1 diabetes. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2007;1103:45–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Harrison LC, Honeyman MC, Steele CE, Stone NL, Sarugeri E, Bonifacio E, Couper JJ, Colman PG: Pancreatic β-cell function and immune responses to insulin after administration of intranasal insulin to humans at risk for type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004;27:2348–2355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kupila A, Sipilä J, Keskinen P, Simell T, Knip M, Pulkki K, Simell O: Intranasally administered insulin intended for prevention of type 1 diabetes–a safety study in healthy adults. Diabete Metab Res Rev 2003;19:415–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Petersen JS, Bregenholt S, Apostolopolous V, Homann D, Wolfe T, Hughes A, De Jongh K, Wang M, Dyrberg T, Von Herrath MG: Coupling of oral human or porcine insulin to the B subunit of cholera toxin (CTB) overcomes critical antigenic differences for prevention of type I diabetes. Clin Exp Immunol 2003;134:38–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Pozzilli P: The DPT-1 trial: a negative result with lessons for future type 1 diabetes prevention. Diabete Metab Res Rev 2002;18:257–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Thrower SL, James L, Hall W, Green KM, Arif S, Allen JS, Van-Krinks C, Lozanoska-Ochser B, Marquesini L, Brown S, Wong FS, Dayan CM, Peakman M: Proinsulin peptide immunotherapy in type 1 diabetes: report of a first-in-man Phase I safety study. Clin Exp Immunol 2009;155:156–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Arif S, Tree TI, Astill TP, Tremble JM, Bishop AJ, Dayan CM, Roep BO, Peakman M: Autoreactive T cell responses show proinflammatory polarization in diabetes but a regulatory phenotype in health. J Clin Invest 2004;113:451-463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ellis RJ, Varela-Calvino R, Tree TI, Peakman M: HLA class II molecules on haplotypes associated with type 1 diabetes exhibit similar patterns of binding affinities for coxsackievirus P2C peptides. Immunology 2005;116:337–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Peakman M, Stevens EJ, Lohmann T, Narendran P, Dromey J, Alexander A, Tomlinson AJ, Trucco M, Gorga JC, Chicz RM: Naturally processed and presented epitopes of the islet cell autoantigen IA-2 eluted from HLA-DR4. J Clin Invest 1999;104:1449–1457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wilson SB, Kent SC, Patton KT, Orban T, Jackson RA, Exley M, Porcelli S, Schatz DA, Atkinson MA, Balk SP, Strominger JL, Hafler DA: Extreme Th1 bias of invariant Valpha24JalphaQ T cells in type 1 diabetes. Nature 1998;391:177–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Herold KC, Burton JB, Francois F, Poumian-Ruiz E, Glandt M, Bluestone JA: Activation of human T cells by FcR nonbinding anti-CD3 mAb, hOKT3gamma1(Ala-Ala). J Clin Invest 2003;111:409–418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sanda S, Roep BO, von Herrath M: Islet antigen specific IL-10+ immune responses but not CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ cells at diagnosis predict glycemic control in type 1 diabetes. Clin Immunol 2008;127:138–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Pihoker C, Gilliam LK, Hampe CS, Lernmark A: Autoantibodies in diabetes. Diabetes 2005;54(Suppl. 2):S52–S61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Martin S, Wolf-Eichbaum D, Duinkerken G, Scherbaum WA, Kolb H, Noordzij JG, Roep BO: Development of type 1 diabetes despite severe hereditary B-lymphocyte deficiency. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1036–1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zouali M: B lymphocytes—chief players and therapeutic targets in autoimmune diseases. Front Biosci 2008;13:4852-4861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Butty V, Campbell C, Mathis D, Benoist C: Impact of diabetes susceptibility loci on progression from pre-diabetes to diabetes in at-risk individuals of the diabetes prevention trial-type 1 (DPT-1). Diabetes 2008;57:2348–2359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Huurman VA, van der Meide PE, Duinkerken G, Willemen S, Cohen IR, Elias D, Roep BO: Immunological efficacy of heat shock protein 60 peptide DiaPep277 therapy in clinical type I diabetes. Clin Exp Immunol 2008;152:488–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. James EA, LaFond R, Durinovic-Bello I, Kwok W: Visualizing antigen specific CD4+ T cells using MHC class II tetramers. J Vis Exp (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Reijonen H, Mallone R, Heninger AK, Laughlin EM, Kochik SA, Falk B, Kwok WW, Greenbaum C, Nepom GT: GAD65-specific CD4+ T-cells with high antigen avidity are prevalent in peripheral blood of patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2004;53:1987–1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Reijonen H, Novak EJ, Kochik S, Heninger A, Liu AW, Kwok WW, Nepom GT: Detection of GAD65-specific T-cells by major histocompatibility complex class II tetramers in type 1 diabetic patients and at-risk subjects. Diabetes 2002;51:1375–1382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Nagata M, Kotani R, Moriyama H, Yokono K, Roep BO, Peakman M: Detection of autoreactive T cells in type 1 diabetes using coded autoantigens and an immunoglobulin-free cytokine ELISPOT assay: report from the fourth immunology of diabetes society T cell workshop. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2004;1037:10–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Mallone R, Martinuzzi E, Blancou P, Novelli G, Afonso G, Dolz M, Bruno G, Chaillous L, Chatenoud L, Bach JM, van Endert P: CD8+ T-cell responses identify β-cell autoimmunity in human type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2007;56:613–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Roep BO: Islet autoreactive CD8 T-cells in type 1 diabetes: licensed to kill? Diabetes 2008;57:1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Skowera A, Ellis RJ, Varela-Calviño R, Arif S, Huang GC, Van-Krinks C, Zaremba A, Rackham C, Allen JS, Tree TI, Zhao M, Dayan CM, Sewell AK, Unger W, Drijfhout JW, Ossendorp F, Roep BO, Peakman M: CTLs are targeted to kill beta cells in patients with type 1 diabetes through recognition of a glucose-regulated preproinsulin epitope. J Clin Invest 2008;118:3390–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Barnett BP, Arepally A, Karmarkar PV, Qian D, Gilson WD, Walczak P, Howland V, Lawler L, Lauzon C, Stuber M, Kraitchman DL, Bulte JW: Magnetic resonance-guided, real-time targeted delivery and imaging of magnetocapsules immunoprotecting pancreatic islet cells. Nat Med 2007;13:986–991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Souza F, Simpson N, Raffo A, Saxena C, Maffei A, Hardy M, Kilbourn M, Goland R, Leibel R, Mann JJ, Van Heertum R, Harris PE: Longitudinal noninvasive PET-based beta cell mass estimates in a spontaneous diabetes rat model. J Clin Invest 2006;116:1506–1513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Turvey SE, Swart E, Denis MC, Mahmood U, Benoist C, Weissleder R, Mathis D: Noninvasive imaging of pancreatic inflammation and its reversal in type 1 diabetes. J Clin Invest 2005;115:2454–2461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Dantal J, Soulillou JP: Immunosuppressive drugs and the risk of cancer after organ transplantation. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1371–1373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Homann D, Holz A, Bot A, Coon B, Wolfe T, Petersen J, Dyrberg TP, Grusby MJ, von Herrath MG: Autoreactive CD4+ T cells protect from autoimmune diabetes via bystander suppression using the IL-4/Stat6 pathway. Immunity 1999;11:463–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Tang Q, Henriksen KJ, Bi M, Finger EB, Szot G, Ye J, Masteller EL, McDevitt H, Bonyhadi M, Bluestone JA: In vitro-expanded antigen-specific regulatory T cells suppress autoimmune diabetes. J Exp Med 2004;199:1455–1465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Daniel D, Wegmann DR: Protection of nonobese diabetic mice from diabetes by intranasal or subcutaneous administration of insulin peptide B-(9–23). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996;93:956–960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Hutchings P, Cooke A: Protection from insulin dependent diabetes mellitus afforded by insulin antigens in incomplete Freund's adjuvant depends on route of administration. J Autoimmun 1998;11:127–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Muir A, Peck A, Clare-Salzler M, Song YH, Cornelius J, Luchetta R, Krischer J, Maclaren N: Insulin immunization of nonobese diabetic mice induces a protective insulitis characterized by diminished intraislet interferon-gamma transcription. J Clin Invest 1995;95:628–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Alleva DG, Gaur A, Jin L, Wegmann D, Gottlieb PA, Pahuja A, Johnson EB, Motheral T, Putnam A, Crowe PD, Ling N, Boehme SA, Conlon PJ: Immunological characterization and therapeutic activity of an altered-peptide ligand, NBI-6024, based on the immunodominant type 1 diabetes autoantigen insulin B-chain (9–23) peptide. Diabetes 2002;51:2126–2134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Di Lorenzo TP, Peakman M, Roep BO: Translational mini-review series on type 1 diabetes: systematic analysis of T cell epitopes in autoimmune diabetes. Clin Exp Immunol 2007;148:1–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Agardh CD, Cilio CM, Lethagen A, Lynch K, Leslie RD, Palmér M, Harris RA, Robertson JA, Lernmark A: Clinical evidence for the safety of GAD65 immunomodulation in adult-onset autoimmune diabetes. J Diabetes Complications 2005;19:238–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Hinke SA: Diamyd, an alum-formulated recombinant human GAD65 for the prevention of autoimmune diabetes. Curr Opin Mol Ther 2008;10:516–525 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Petersen JS, Mackay P, Plesner A, Karlsen A, Gotfedsen C, Verland S, Michelsen B, Dyrberg T: Treatment with GAD65 or BSA does not protect against diabetes in BB rats. Autoimmunity 1997;25:129–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Ramiya VK, Shang XZ, Wasserfall CH, Maclaren NK: Effect of oral and intravenous insulin and glutamic acid decarboxylase in NOD mice. Autoimmunity 1997;26:139–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Tisch R, Liblau RS, Yang XD, Liblau P, McDevitt HO: Induction of GAD65-specific regulatory T-cells inhibits ongoing autoimmune diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. Diabetes 1998;47:894–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Bowman M, Atkinson MA: Heat shock protein therapy fails to prevent diabetes in NOD mice. Diabetologia 2002;45:1350–1351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Schloot NC, Meierhoff G, Lengyel C, Vándorfi G, Takács J, Pánczél P, Barkai L, Madácsy L, Oroszlán T, Kovács P, Sütö G, Battelino T, Hosszufalusi N, Jermendy G: Effect of heat shock protein peptide DiaPep277 on beta-cell function in paediatric and adult patients with recent-onset diabetes mellitus type 1: two prospective, randomized, double-blind phase II trials. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2007;23:276–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Raz I, Avron A, Tamir M, Metzger M, Symer L, Eldor R, Cohen IR, Elias D: Treatment of new-onset type 1 diabetes with peptide DiaPep277 is safe and associated with preserved beta-cell function: extension of a randomized, double-blind, phase II trial. Diabete Metab Res Rev 2007;23:292–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Hermitte L, Vialettes B, Atlef N, Payan MJ, Doll N, Scheimann A, Vague P: High dose nicotinamide fails to prevent diabetes in BB rats. Autoimmunity 1989;5:79–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Piercy V, Toseland CD, Turner NC: Acceleration of the development of diabetes in obese diabetic (db/db) mice by nicotinamide: a comparison with its antidiabetic effects in non-obese diabetic mice. Metabolism 2000;49:1548–1554 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Yamada K, Nonaka K, Hanafusa T, Miyazaki A, Toyoshima H, Tarui S: Preventive and therapeutic effects of large-dose nicotinamide injections on diabetes associated with insulitis: an observation in nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice. Diabetes 1982;31:749–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. von Herrath MG, Coon B, Wolfe T, Chatenoud L: Nonmitogenic CD3 antibody reverses virally induced (rat insulin promoter-lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus) autoimmune diabetes without impeding viral clearance. J Immunol 2002;168:933–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Chatenoud L, Thervet E, Primo J, Bach JF: Anti-CD3 antibody induces long-term remission of overt autoimmunity in nonobese diabetic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994;91:123–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Hu CY, Rodriguez-Pinto D, Du W, Ahuja A, Henegariu O, Wong FS, Shlomchik MJ, Wen L: Treatment with CD20-specific antibody prevents and reverses autoimmune diabetes in mice. J Clin Invest 2007;117:3857–3867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Xiu Y, Wong CP, Bouaziz JD, Hamaguchi Y, Wang Y, Pop SM, Tisch RM, Tedder TF: B lymphocyte depletion by CD20 monoclonal antibody prevents diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice despite isotype-specific differences in Fc gamma R effector functions. J Immunol 2008;180:2863–2875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Giannoukakis N, Rudert WA, Ghivizzani SC, Gambotto A, Ricordi C, Trucco M, Robbins PD: Adenoviral gene transfer of the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist protein to human islets prevents IL-1β–induced β-cell impairment and activation of islet cell apoptosis in vitro. Diabetes 1999;48:1730–1736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Narang AS, Sabek O, Gaber AO, Mahato RI: Co-expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist improves human islet survival and function. Pharm Res 2006;23:1970–1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Saldeen J, Sandler S, Bendtzen K, Welsh N: Liposome-mediated transfer of IL-1 receptor antagonist gene to dispersed islet cells does not prevent recurrence of disease in syngeneically transplanted NOD mice. Cytokine 2000;12:405–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Sandberg JO, Eizirik DL, Sandler S: IL-1 receptor antagonist inhibits recurrence of disease after syngeneic pancreatic islet transplantation to spontaneously diabetic non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice. Clin Exp Immunol 1997;108:314–317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Winter WE, Schatz D: Prevention strategies for type 1 diabetes mellitus: current status and future directions. BioDrugs 2003;17:39–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Watanabe T, Masuyama J, Sohma Y, Inazawa H, Horie K, Kojima K, Uemura Y, Aoki Y, Kaga S, Minota S, Tanaka T, Yamaguchi Y, Kobayashi T, Serizawa I: CD52 is a novel costimulatory molecule for induction of CD4+ regulatory T cells. Clin Immunol 2006;120:247–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Shehadeh N, Calcinaro F, Bradley BJ, Bruchim I, Vardi P, Lafferty KJ: Effect of adjuvant therapy on development of diabetes in mouse and man. Lancet 1994;343:706–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Ban L, Zhang J, Wang L, Kuhtreiber W, Burger D, Faustman DL: Selective death of autoreactive T cells in human diabetes by TNF or TNF receptor 2 agonism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:13644–13649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Christen U, von Herrath MG: Transgenic animal models for type 1 diabetes: linking a tetracycline-inducible promoter with a virus-inducible mouse model. Transgenic Res 2002;11:587–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Christen U, Wolfe T, Mohrle U, Hughes AC, Rodrigo E, Green EA, Flavell RA, von Herrath MG: A dual role for TNF-alpha in type 1 diabetes: islet-specific expression abrogates the ongoing autoimmune process when induced late but not early during pathogenesis. J Immunol 2001;166:7023–7032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Kodama S, Davis M, Faustman DL: The therapeutic potential of tumor necrosis factor for autoimmune disease: a mechanistically based hypothesis. Cell Mol Life Sci 2005;62:1850–1862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Kuhtreiber WM, Kodama S, Burger DE, Dale EA, Faustman DL: Methods to characterize lymphoid apoptosis in a murine model of autoreactivity. J Immunol Methods 2005;306:137–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Ryu S, Kodama S, Ryu K, Schoenfeld DA, Faustman DL: Reversal of established autoimmune diabetes by restoration of endogenous beta cell function. J Clin Invest 2001;108:63–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Hadjiyanni I, Baggio LL, Poussier P, Drucker DJ: Exendin-4 modulates diabetes onset in nonobese diabetic mice. Endocrinology 2008;149:1338–1349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Rabinovitch A, Suarez-Pinzon WL, Shapiro AM, Rajotte RV, Power R: Combination therapy with sirolimus and interleukin-2 prevents spontaneous and recurrent autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice. Diabetes 2002;51:638–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Suarez-Pinzon WL, Lakey JR, Brand SJ, Rabinovitch A: Combination therapy with epidermal growth factor and gastrin induces neogenesis of human islet {beta}-cells from pancreatic duct cells and an increase in functional {beta}-cell mass. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90:3401–3409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Suarez-Pinzon WL, Rabinovitch A: Combination therapy with epidermal growth factor and gastrin delays autoimmune diabetes recurrence in nonobese diabetic mice transplanted with syngeneic islets. Transplant Proc 2008;40:529–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Suarez-Pinzon WL, Yan Y, Power R, Brand SJ, Rabinovitch A: Combination therapy with epidermal growth factor and gastrin increases β-cell mass and reverses hyperglycemia in diabetic NOD mice. Diabetes 2005;54:2596–2601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Suarez-Pinzon WL, Lakey JR, Rabinovitch A: Combination therapy with glucagon-like peptide-1 and gastrin induces beta-cell neogenesis from pancreatic duct cells in human islets transplanted in immunodeficient diabetic mice. Cell Transplant 2008;17:631–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Suarez-Pinzon WL, Power RF, Yan Y, Wasserfall C, Atkinson M, Rabinovitch A: Combination therapy with glucagon-like peptide-1 and gastrin restores normoglycemia in diabetic NOD mice. Diabetes 2008;57:3281–3288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]