Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To examine the recent suggestion that impaired fasting glucose may protect against depression, whereas a diagnosis of diabetes might then result in depression.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Cross-sectional analysis of 4,228 adults (mean age 60.7 years, 73.0% men) who underwent oral glucose tolerance testing and completed the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D).

RESULTS

After adjustment for demographic factors, health behaviors, and clinical measurements (BMI, waist circumference, lipid profile, and blood pressure), there was a U-shaped association between fasting glucose and depression (Pcurve = 0.001), with elevated CES-D at low and very high glucose levels. This finding was replicable with 2-h postload glucose (P = 0.11) and A1C (P = 0.007).

CONCLUSIONS

The U-shaped association between blood glucose and CES-D, with the lowest depression risk seen among those in the normoglycemic range of A1C, did not support the hypothesized protective effect of hyperglycemia.

The association between type 2 diabetes and depression, both major public health challenges, remains unclear (1–8). In a recent U.S. report, people with type 2 diabetes had an increased risk of depressive symptoms, whereas in nondiabetic individuals higher impaired fasting glucose (IFG) appeared to confer protection against depression (8). Although an increased prevalence of depression in people receiving a diagnosis of a pernicious chronic disease such as type 2 diabetes is perhaps unsurprising, the apparent counterintuitive protective effect of IFG warrants further scrutiny.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Data were from the Whitehall II study (9). In the 2003 and 2004 data collection phase, 4,228 men and women aged 50–74 years completed a depression questionnaire and, if without known diabetes, underwent an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). Venous blood samples were taken after at least 8-h fasting, before OGTT, and at 2-h postadministration of a 75 g glucose solution. Blood glucose was measured using the glucose oxidase method (10) on a YSI MODEL 2300 STAT PLUS Analyzer (YSI Corporation, Yellow Springs, OH; mean coefficient of variation [CV] 1.4–3.1%) (11). Diabetes was defined by a fasting glucose ≥7.0 mmol/l, a 2-h postload glucose ≥11.1 mmol/l, reported doctor-diagnosed diabetes, or use of diabetes medication (12). In nondiabetic participants, we classified moderate hyperglycemia as IFG (fasting glucose 5.6–6.9 mmol/l) and impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) (2-h postload glucose 7.8–11.0 mmol/l) (12). A1C was measured in whole blood with a calibrated high-performance liquid chromatography system (CV 0.8%).

Depressive symptoms were assessed with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D) summary score (13), a measure that has been validated among diabetic patients (14). Ethnicity (Caucasian or non-Caucasian), BMI (weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared [kg/m2]), waist circumference (cm), systolic and diastolic blood pressure (mmHg), HDL and LDL cholesterol (mmol/l), triglycerides (mmol/l), current smoking (yes/no), alcohol consumption (none, 1–3 units per day, or >3 units per day), and physical inactivity (<2.5 h moderate and >1 h vigorous exercise per week) were measured according to standardized protocols.

Statistical analyses are based on between 3,945 (93% of the 4,228) and 4,228 (100%) of the eligible participants because there were missing data for some of the various glucose parameters. Values for triglycerides were log transformed prior to analyses because of skewed distribution. We used linear regression analysis to model the associations of IFG and IGT with the CES-D score. The shape of the associations between fasting glucose, postload glucose, A1C, and CES-D were studied by treating all these measures as continuous variables. To test for curvilinear trends, a squared term of the glycemic measures was added to an equation containing the linear term. The models were adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, and clinical characteristics (BMI, waist circumference, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, HDL and LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and physical activity). Subsidiary analyses examined these associations in subgroups and in the whole cohort with glucose levels measured repeatedly (in 1997–1999 and in 2003–2004) and with a dichotomized CES-D score (<16 vs. ≥16). The statistical tests were performed with STATA version 10.1.

RESULTS

Of the 4,228 participants, 2,038 (73.0%) were men and 3,895 (92.1%) Caucasian. Mean ± SD age was 60.7 ± 6.0 years, and the levels of clinical characteristics were 128 ± 17 and 74 ± 10 mmHg for systolic and diastolic blood pressure, respectively, 1.6 ± 0.4 mmol/l for HDL cholesterol, 3.58 ± 1.9 mmol/l for LDL cholesterol, 26.7 ± 4.4 kg/m2 for BMI, and 94.2 ± 10.7 cm (men) and 84.3 ± 13.0 cm (women) for waist circumference. For triglycerides, median (interquartile range) was 1.2 (0.8–1.6) mmol/l. Of the participants, 7.9% were current smokers, 16.0% were physically inactive, 17.8% consumed more than 3 units of alcohol per day, and 16.2% did not consume alcohol regularly. Overall CES-D mean score was 9.9 ± 6.6.

Fasting glucose

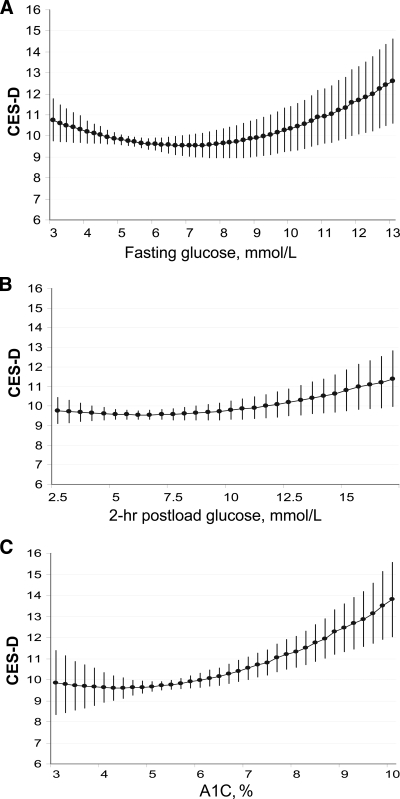

Mean ± SD for fasting glucose was 5.55 ± 1.51 mmol/l. Compared with participants with normal fasting glucose (n = 3,038; CES-D 9.9 ± 6.7), those with IFG (n = 735) showed a marginally reduced CES-D score (9.0 ± 6.1; P = 0.05), whereas those with diabetes (n = 455) showed an elevated CES-D score (11.2 ± 7.0; P = 0.002) after taking into account age, sex, and ethnicity. As shown in Fig. 1A, there was a U-shaped association between fasting glucose and CES-D (Pcurve = 0.001 after adjustment for age, sex, and ethnicity; n = 3,986), with elevated CES-D values at glucose levels <4.5 and >9.0 mmol/l. The curvilinear trend was robust to additional adjustment for clinical characteristics (P = 0.001).

Figure 1.

Age-, sex, and ethnicity-adjusted associations of fasting glucose (A), 2-h postload glucose (B), and A1C (C) with self-reported depressive symptoms assessed with CES-D.

Postload glucose

Mean ± SD for postload glucose was 6.38 ± 2.09 mmol/l. IGT (n = 423; CES-D 9.49 ± 6.58) was not associated with CES-D (P = 0.75). However, there was a U-shaped association between postload glucose and CES-D (Fig. 1B; n = 3,455; Pcurve = 0.05 after adjustment for age, sex, and ethnicity; Pcurve = 0.11 after additional adjustment for clinical char- acteristics).

A1C

Mean ± SD for A1C was 5.36 ± 0.73%. Again, a curvilinear association with CES-D was evident (P = 0.04; n = 4,160; Fig. 1C). The lowest CES-D scores were between A1C levels 4.0 and 5.5% (nadir 4.4% in age-, sex-, and ethnicity-adjusted model). The curvilinear trend remained after additional adjustment for all clinical characteristics (P = 0.007).

Subsidiary analyses

There were no differences in the U-shaped associations of the three glucose measures with CES-D between men and women or between Caucasian and non-Caucasian participants (all Pinteraction = 0.15–0.74). Using the average of repeated fasting and postload glucose measurements as exposure variables replicated the U-shaped associations (Pcurve = 0.01). With the dichotomised CES-D score, the U-shaped trend reached statistical significance for repeatedly measured fasting glucose (Pcurve = 0.02), but for the other glucose measures conventional statistical significance was not met (Pcurve = 0.09–0.26). (See supplemental Table 1, available in an online appendix at http://care.diabetesjournals.org/cgi/content/full/dc09-0716/DC1.)

CONCLUSIONS

Our results show slightly lower levels of depressive symptoms among nondiabetic individuals with IFG. However, this finding was generated by a U-shaped association between fasting glucose and CES-D with elevated depression scores seen at both ends of the glucose distribution, a finding that was replicated for 2-h postload glucose and A1C. Although low depression scores were observed both at normal and pre-diabetic ranges of fasting and postload glucose, findings from long-term glucose levels (A1C) suggested that normoglycemic individuals had the lowest depression risk. Our results do not support a protective effect of hyperglycemia against depressive symptoms. Future research should examine whether our findings are generalizable to other populations and whether they are applicable to clinical depression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Whitehall II study has been supported by grants from the Medical Research Council (MRC); British Heart Foundation; Health and Safety Executive; Department of Health; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL36310), National Institutes of Health (NIH); National Institute on Aging (AG13196), NIH; Agency for Health Care Policy Research (HS06516); and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Networks on Successful Midlife Development and Socioeconomic Status and Health. M.K. is supported by the Academy of Finland and the BUPA Foundation, U.K.; G.D.B. is a Wellcome Trust Research Fellow; A.S.-M. is supported by a European Young Investigator award from the European Science Foundation; M.G.M. is supported by an MRC Research Professorship; and D.A.L. works in a center that receives some core funding from the U.K. MRC.

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Footnotes

The funding bodies have not influenced the conduct of this study or any of its conclusions. The views expressed here are those of authors and not necessarily those of any funding body.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

References

- 1. Polsky D, Doshi JA, Marcus S, Oslin D, Rothbard A, Thomas N, Thompson CL: Long-term risk for depressive symptoms after a medical diagnosis. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:1260–1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Palinkas LA, Lee PP, Barrett-Connor E: A prospective study of type 2 diabetes and depressive symptoms in the elderly: the Rancho Bernardo Study. Diabet Med 2004;21:1185–1191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. de Jonge P, Roy JF, Saz P, Marcos G, Lobo A: Prevalent and incident depression in community-dwelling elderly persons with diabetes mellitus: results from the ZARADEMP project. Diabetologia 2006;49:2627–2633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brown LC, Majumdar SR, Newman SC, Johnson JA: Type 2 diabetes does not increase risk of depression. CMAJ 2006;175:42-46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kim JM, Stewart R, Kim SW, Yang SJ, Shin IS, Yoon JS: Vascular risk factors and incident late-life depression in a Korean population. Br J Psychiatry 2006;189:26–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maraldi C, Volpato S, Penninx BW, Yaffe K, Simonsick EM, Strotmeyer ES, Cesari M, Kritchevsky SB, Perry S, Ayonayon HN, Pahor M: Diabetes mellitus, glycemic control, and incident depressive symptoms among 70- to 79-year-old persons: the health, aging, and body composition study. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1137–1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boyle SH, Surwit RS, Georgiades A, Brummett BH, Helms MJ, Williams RB, Barefoot JC: Depressive symptoms, race, and glucose concentrations: the role of cortisol as mediator. Diabetes Care 2007;30:2484–2488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Golden SH, Lazo M, Carnethon M, Bertoni AG, Schreiner PJ, Roux AV, Lee HB, Lyketsos C: Examining a bidirectional association between depressive symptoms and diabetes. JAMA 2008;299:2751–2759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marmot M, Brunner E: Cohort profile: the Whitehall II study. Int J Epidemiol 2005;34:251–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cooper GR: Methods for determining the amount of glucose in blood. CRC Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 1973;4:101–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Astles JR, Sedor FA, Toffaletti JG: Evaluation of the YSI 2300 glucose analyzer: algorithm-corrected results are accurate and specific. Clin Biochem 1996;29:27–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 2003;26(Suppl. 1):S5–S20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Radloff LS, Locke BZ: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). In Handbook of Psychiatric Measures. Rush AJ. Ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000, p. 523–526 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fisher L, Chesla CA, Mullan JT, Skaff MM, Kanter RA: Contributors to depression in Latino and European-American patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2001;24:1751–1757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.