Abstract

Genetic manipulation of the category B select agents Burkholderia pseudomallei and Burkholderia mallei has been stifled due to the lack of compliant selectable markers. Hence, there is a need for additional select-agent-compliant selectable markers. We engineered a selectable marker based on the gat gene (encoding glyphosate acetyltransferase), which confers resistance to the common herbicide glyphosate (GS). To show the ability of GS to inhibit bacterial growth, we determined the effective concentrations of GS against Escherichia coli and several Burkholderia species. Plasmids based on gat, flanked by unique flip recombination target (FRT) sequences, were constructed for allelic-replacement. Both allelic-replacement approaches, one using the counterselectable marker pheS and the gat-FRT cassette and one using the DNA incubation method with the gat-FRT cassette, were successfully utilized to create deletions in the asd and dapB genes of wild-type B. pseudomallei strains. The asd and dapB genes encode an aspartate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase (BPSS1704, chromosome 2) and dihydrodipicolinate reductase (BPSL2941, chromosome 1), respectively. Mutants unable to grow on media without diaminopimelate (DAP) and other amino acids of this pathway were PCR verified. These mutants displayed cellular morphologies consistent with the inability to cross-link peptidoglycan in the absence of DAP. The B. pseudomallei 1026b Δasd::gat-FRT mutant was complemented with the B. pseudomallei asd gene on a site-specific transposon, mini-Tn7-bar, by selecting for the bar gene (encoding bialaphos/PPT resistance) with PPT. We conclude that the gat gene is one of very few appropriate, effective, and beneficial compliant markers available for Burkholderia select-agent species. Together with the bar gene, the gat cassette will facilitate various genetic manipulations of Burkholderia select-agent species.

Members of the genus Burkholderia, comprising more than 40 different species, are extremely diverse gram-negative, non-spore-forming bacilli. Many Burkholderia species exist as innocuous soil saprophytes or plant pathogens (47), while others cause human and animal diseases. Among these human and animal pathogens are the etiological agents of melioidosis (Burkholderia pseudomallei) and glanders (Burkholderia mallei) (9, 50, 51). Melioidosis is an emerging infectious disease generally considered endemic to Southeast Asia and Northern Australia (12). Positive diagnoses in many tropical countries around the world have expanded the global awareness of melioidosis (3, 15, 24, 25, 28, 35, 39, 42, 52). In contrast to the ubiquitous nature of B. pseudomallei, B. mallei is also a highly infectious agent causing glanders, a predominantly equine disease (34, 50). B. mallei, a clone derived from genomic downsizing of B. pseudomallei, has been used in biowarfare (17). This historical significance, along with the low infectious dose and the route of infection, has contributed to the decision by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to classify these two microbes as category B select agents (43).

Classification of B. pseudomallei as a select agent has stimulated interest and research into the pathogenesis of melioidosis, necessitating the development of appropriate tools for genetic manipulation. In the struggle to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of pathogenesis, selectable markers are indispensable genetic tools (45). Current CDC regulations prohibit the cloning of clinically important antibiotic resistance genes into human, animal, or plant select-agent pathogens if the transfer could compromise the ability to treat or control the disease. The only antibiotic markers currently approved for use in B. pseudomallei are based on resistance to aminoglycosides (gentamicin, kanamycin, and zeocin) (45). However, the efficacy of these markers is limited, due to high levels of aminoglycoside resistance inherent within the Burkholderia genus and high levels of spontaneous aminoglycoside resistance in B. pseudomallei (10, 19, 41). In addition, the use of aminoglycosides (e.g., gentamicin) for selection may require aminoglycoside efflux pump mutants (10, 33). Another potential drawback is that efflux pumps play a major role in bacterial physiology, and mutating them may change the pathogenic traits under investigation (7, 40). A more logical approach employs alternative, non-antibiotic-selectable markers conferring resistance to compounds that are not potentially important in clinical treatment.

Very few non-antibiotic resistance markers have been utilized successfully for Burkholderia species. A non-antibiotic-selectable-marker based on tellurite resistance (Telr) has been successfully developed and used with Pseudomonas putida, Pseudomonas fluorescens, and Burkholderia thailandensis (2, 27, 44). The engineering of Telr-FRT (flip recombination target) cassettes, coupled to FRT sequences, could be used to generate unmarked mutations and allow recycling of the Telr selectable-marker (2). In addition, utilization of Flp-FRT resistance cassettes to generate mutants allows downstream modification and manipulation such as fusion integration (29). However, the disadvantage of the Telr-cassette is the number of genes required (kilA-telA-telB) and the large size (>3 kb), making it less likely to obtain PCR products for allelic replacement by natural transformation (46). Another potentially useful non-antibiotic-selectable marker is based on the bar gene, encoding resistance to bialaphos or its degradation product, phosphinothricin (PPT) (49). PPT inhibits glutamine synthetase in plants (48), starving the cell for glutamine, and the bar gene has been used successfully as a selection marker in gram-negative bacteria (21). For select-agent Burkholderia species, however, the PPT MIC was found to be greater than 1,024 μg/ml (M. Frazier, K. Choi, A. Kumar, C. Lopez, R. R. Karkhoff-Schweizer, and H. P. Schweizer, presented at the American Society for Microbiology Biodefense and Emerging Diseases Research Meeting, Washington, DC, 2007). We have found the effective concentration of PPT for B. pseudomallei and B. mallei to be ∼2.5% (25,000 μg/ml [data not shown]). The high concentration of PPT required for selection in these species may be costly, considering that purified PPT costs ∼$380 per g. Therefore, further development of non-antibiotic resistance markers, as well as a more economical source of herbicide for use with restricted select-agent species, is needed.

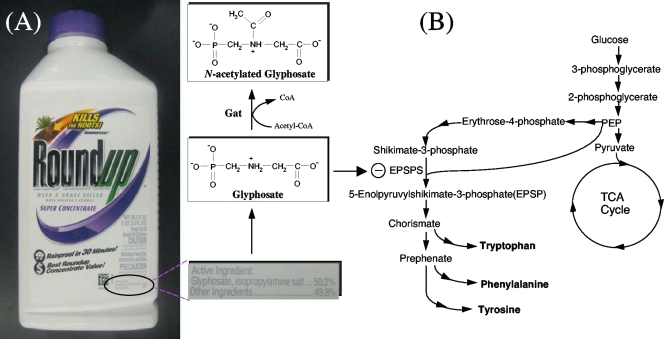

Work by Castle et al. (5) generated a highly active glyphosate N-acetyltransferase (GAT) enzyme for plant engineering, making it possible to utilize the gat gene as an effective non-antibiotic resistance marker for bacterial selection with glyphosate (GS). The commonly used herbicide GS inhibits the 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phospate synthase (EPSPS) of plants through competition with phosphoenolpyruvate for overlapping binding sites on EPSPS (14), depriving plants of three aromatic amino acids (Fig. 1). Since humans and animals obtain tryptophan and phenylalanine (giving rise to tyrosine) through dietary intake, GS is relatively nontoxic. Like plants, bacteria must make these amino acids, when they are lacking, from basic precursors. GS has been found to be inhibitory to a variety of bacteria, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, and Bradyrhizobium japonicum (16, 55), while other bacterial strains are able to metabolize low concentrations of GS (26, 31). Although B. pseudomallei has been reported to have two genes (glpA and glpB) for GS degradation and metabolism (38), our searches of all available genomes of Burkholderia species in GenBank yielded no glpA or glpB genes within this genus. GS resistance by bacteria has been documented through EPSPS target mutations or GS detoxification mechanisms (36). However, these mechanisms did not confer resistance to relatively high GS concentrations. More recently, directed evolution of the gat gene, based on various bacterial gat sequences and selection in E. coli, yielded a very active GAT protein sequence with an efficiency increase of nearly 4 orders of magnitude (5), holding promise as an appropriate non-antibiotic resistance marker for select-agent species.

FIG. 1.

(A) A 946-ml bottle of the “superconcentrated” herbicide Roundup used in this study, available for ∼$50 from most local hardware stores and garden or farm supply centers. The active ingredient, 50% GS, is indicated on the label, and the chemical structure of GS is shown. GAT, encoded by the gat gene, catalyzes the inactivation of GS via N acetylation. (B) Pathways of aromatic amino acid biosynthesis. GS inhibits the enzyme EPSPS, which is required for the biosynthesis of aromatic amino acids, thus starving bacteria for tyrosine, phenylalanine, and tryptophan. PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; TCA cycle, tricarboxylic acid cycle.

Here we engineered and tested a novel non-antibiotic-selectable-marker (gat) for use in the select agent B. pseudomallei. GS is the active ingredient in Roundup, which was used for selection (Fig. 1). The effective compound GS is readily available, inexpensive, relatively nontoxic, very soluble, and not clinically important, and it yields tight selection. The engineered gat marker (563 bp) was optimized for Burkholderia codon usage and adapted (with a Burkholderia rpsL promoter) for use in the select agent B. pseudomallei. Effective concentrations of GS for several species of Burkholderia, including the select agents B. pseudomallei and B. mallei, were determined. Using the gat gene, we created deletion mutants of the essential B. pseudomallei asd and B. pseudomallei dapB (asdBp and dapBBp) genes (encoding aspartate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase and dihydrodipicolinate reductase, respectively) in two wild-type B. pseudomallei strains. The ΔasdBp mutant of B. pseudomallei showed a phenotypic defect consistent with the lack of diaminopimelate (DAP) for cell wall cross-linking. Complementation of the B. pseudomallei ΔasdBp mutant with the asdBp gene located on a site-specific transposon, mini-Tn7-bar, was successful by using an inexpensive source of PPT for selection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and culture conditions.

All strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Tables 1 and 2. All manipulations with B. pseudomallei and B. mallei were conducted in a CDC/USDA-approved and -registered BSL3 facility at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, and experiments with these select agents were performed with BSL3 practices by following the recommendations of Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories, 5th edition (51a).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this studya

| Strain | Lab IDb | Relevant properties | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | |||

| K-12 | E0577 | Wild type; F+ | Coli Genetic Stock Center |

| EPMax10B-pir116/Δasd::Gmr | E1345 | Gmr; F− λ−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80dlacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 deoR recA1 endA1 araD139 Δ(ara leu)7697 galU galK rpsL nupG Tn-pir116-FRT2 Δasd::Gmr-wFRT | —c |

| EPMax10B-lacIq/pir/leu+/Δasd::Gmr | E1951 | Gmr; F− λ−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80dlacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 deoR recA1 endA1 galU galK rpsL nupG lacIq-FRT8 pir::FRT4 Δasd::Gmr-wFRT | —c |

| EPMax10B-pir116/Δasd/Δtrp::Gmr/ mob-Kmr | E1354 | Gmr Kmr; F− λ−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80dlacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 deoR recA1 endA1 araD139 Δ(ara leu)7697 galU galK rpsL nupG Tn-pir116-FRT2 Δasd::wFRT Δtrp::Gmr-FRT5 mob[recA::RP4-2 Tc::Mu-Kmr] | —c |

| EPMax10B-lacIq/pir | E1869 | F− λ−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80dlacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 deoR recA1 endA1 araD139 Δ(ara leu)7697 galU galK rpsL nupG lacIq-FRT8 pir-FRT4 | —c |

| EPMax10B-lacIq/pir/leu+ | E1889 | F− λ−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80dlacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 deoR recA1 endA1 galU galK rpsL nupG lacIq-FRT8 pir-FRT4 | —c |

| GM33 | E0021 | F−λ− IN(rrnD-rrnE)1 dam-3 sup-85 | 32 |

| Burkholderia spp. | |||

| B. dolosa AU0158 | E1551 | Prototroph | J. Goldberg |

| B. cenocepacia | |||

| Bc7 | E1552 | Prototroph | J. Goldberg |

| K56-2 | E1554 | Prototroph; cystic fibrosis isolate | P. Sokol |

| B. mallei ATCC 23344 | B0002 | Wild-type strain; postmortem isolate | 34 |

| B. pseudomallei | |||

| 1026b | B0004 | Wild-type strain; clinical melioidosis isolate | 13 |

| 1026b-ΔasdBp::gat-FRT | B0011 | GSr; 1026b with a gat-FRT cassette inserted into the asdBp gene | This study |

| 1026b-ΔasdBp::gat-FRT/attTn7-bar-asdBp | B0015 | GSr PPTr; 1026b ΔasdBp::gat-FRT mutant with mini-Tn7-bar-asdBp inserted | This study |

| 1026b-ΔdapBBp::gat-FRT | B0013 | GSr; 1026b with a gat cassette inserted into the dapBBp gene | This study |

| K96243 | B0002 | Wild-type strain; clinical melioidosis isolate | 23 |

| K96243-ΔasdBp::gat-FRT | B0007 | GSr; K96243 with a gat cassette inserted into the asdBp gene | This study |

| K96243-ΔdapBBp::gat-FRT | B0010 | GSr; K96243 with a gat cassette inserted into the chromosomal dapBBp gene | This study |

| B. thailandensis E264 | E1298 | Prototroph; environmental isolate | 4 |

Abbreviations and designations: bar, gene encoding bialaphos (PPT) resistance; gat, gene encoding GAT; Gmr, gentamicin resistant; GSr, glyphosate resistant; Kmr, kanamycin resistant; PPTr, PPT resistant.

Please use the laboratory identification number (lab ID) when requesting strains.

Details on the engineering of this strain are to be published elsewhere.

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this studya

| Plasmid | Lab IDb | Relevant properties | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| mini-Tn7-Telr | E1825 | Telr; mini-Tn7 integration vector based on Telr | 29 |

| mini-Tn7-bar | E2218 | PPTr; mini-Tn7 integration vector based on bar | This study |

| mini-Tn7-gat | E1981 | GSr; mini-Tn7 integration vector based on gat | This study |

| mini-Tn7-bar-asdBp | E2226 | PPTr; B. pseudomallei K96243 asdBp gene cloned into mini-Tn7-bar | This study |

| pBAKA | E1624 | Select-agent-compliant allelic-replacement vector based on asdPa | 2 |

| pBAKA-ΔasdBp::gat-FRT | E2062 | GSr; gat-FRT cassette inserted into asdBp | This study |

| pBAKA-dapBBp | E2075 | B. pseudomallei K96243 dapB gene cloned into pBAKA | This study |

| pBAKA-ΔdapBBp::gat-FRT | E2083 | GSr; gat-FRT cassette inserted into dapBBp | This study |

| pBBR1MCS-2 | E1277 | Kmr; broad-host-range cloning vector | 30 |

| pBBR1MCS-2-PCS12-bar | E1773 | Kmr PPTr; broad-host-range cloning vector harboring bar | This study |

| pBBR1MCS-2-PCS12-gat | E1794 | GSr Kmr; broad-host-range cloning vector harboring gat | This study |

| pCAMBIA-1301-bar | E1775 | PPTr; plant transformation vector harboring bar | Cambia |

| pTNS3-asdEc | E1831 | Helper plasmid containing asdEc for Tn7 site-specific transposition system | 29 |

| pUC18 | E0135 | Apr; cloning vector | 53 |

| pUC18-asdBp | E1819 | Apr; cloning vector pUC18 containing asdBp | This study |

| pUC18-ΔasdBp::gat-FRT | E1867 | Apr GSr; cloning vector pUC18 containing asdBp inactivated by gat-FRT | This study |

| pUC57-PS12-gat | E1763 | Apr GSr; cloning vector pUC57 containing B. pseudomallei codon-optimized gat | This study |

| pwFRT-PS12-gat | E1798 | Apr GSr; gat cassette flanked by wild-type FRT | This study |

| pwFRT-PS12-gat-SDM | E1812 | Apr GSr; gat cassette flanked by wild-type FRT after SDM removing an internal SacI site | This study |

| pwFRT-PCS12-gatc | E1929 | Apr GSr; gat cassette flanked by wild-type FRT with the PS12 replaced by the PCS12 | This study |

| pwFRT-PCS12-bar | E2209 | Apr PPTr; bar cassette flanked by wild-type FRT | This study |

| pwFRT-Tpr | E1659 | Tpr; Tpr cassette flanked by wild-type FRT | 2 |

| pwFRT-Telr | E1584 | Telr; Telr cassette flanked by wild-type FRT | 2 |

Apr, ampicillin resistant; PCS12, rpsL promoter of B. cenocepacia; PS12, rpsL promoter of B. pseudomallei.

Please use the laboratory identification number (Lab ID) when requesting plasmids.

Four other FRT mutants exist for this plasmid, where the only sequence difference in the mutated plasmids is within the spacer sequence of each FRT (see Materials and Methods for details).

Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (Difco) was used to culture all E. coli strains. Burkholderia strains (B. pseudomallei, B. mallei, B. thailandensis, Burkholderia cenocepacia, and Burkholderia dolosa) were cultured in LB medium or 1× M9 minimal medium plus 20 mM glucose (MG medium). DAP was prepared in 1 M NaOH as a 100-mg/ml stock and was used when necessary as described previously (2). A ∼1-liter bottle of the “superconcentrated” herbicide Roundup (50% [wt/vol] GS) was purchased at a City Mill hardware store as a source of GS for approximately $50 and was used in this study. Purified GS was purchased from Sigma. We also purchased the herbicide Finale (9.5 liters with 11.33% [wt/vol] PPT) for $125 at a local farm supply store (Pacific Agricultural Sales and Services), and it was used as a source of PPT in this study. MG medium plus GS or PPT was utilized for gat or bar selection, respectively. Since GS blocks the biosynthesis of aromatic amino acids (Fig. 1), it is necessary to use a minimal medium without Phe, Trp, or Tyr (e.g., MG medium). We observed that minimal medium provided with any two aromatic amino acids abolished the selective potential of GS. Likewise, minimal medium lacking glutamine is required for the selection of bar with PPT. Antibiotics and nonantibiotic antibacterial compounds in solid media were utilized as follows: for E. coli, ampicillin at 110 μg/ml, 0.3% GS, kanamycin (Km) at 35 μg/ml, and 0.3% PPT; for B. mallei, 0.2% GS (effective concentration); for B. pseudomallei, 0.3% GS and 2.5% PPT; and for B. thailandensis, Km at 500 μg/ml, 0.04% GS, and 1.5% PPT.

Two derivatives of E. coli EPmax10B (Bio-Rad), one containing lacIq and pir (laboratory identification no. E1869) and the other containing lacIq, pir, and leu+ (E1889), were routinely used as cloning strains in rich and minimal media, respectively. The E. coli conjugal and suicidal strain EPMax10B-pir116-Δasd-mob-Km-Δtrp::Gm (E1354) was used for plasmid mobilization into B. pseudomallei and B. thailandensis. Growth of E. coli Δasd strains was carried out as previously described (2). E. coli strain EPMax10B-pir116-Δasd::Gm (E1345) was used for the cloning of asd-complementing vectors (e.g., pBAKA) (the asd gene encodes aspartate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase). Briefly, selection of E1345 complemented with various asd- and gat-containing constructs (e.g., pBAKA-ΔasdBp::gat-FRT or pBAKA-ΔdapBBp::gat-FRT) was performed on MG-plus-GS medium supplemented with leucine (Leu). To simplify selection and replace strain E1345, EPMax10B-lacIq/pir/leu+/Δasd::Gm (E1951) was later created to select for asd-, bar-, and gat-containing plasmids on MG-plus-PPT or MG-plus-GS medium, so that leucine (Leu) could be omitted from the minimal medium. Selection of asd-, bar-, and gat-containing plasmids in the conjugation-proficient strain E1354 was carried out with MG medium plus Leu, Trp, and GS or PPT; in the absence of a complementing asd gene (e.g., pBBR1MCS-2-PCS12-gat), an additional 1 mM (each) lysine (Lys), methionine (Met),and threonine (Thr) and 100 μg/ml of DAP were added. For selection against E1354 following conjugation, Leu and Trp were omitted from the growth medium. Counterselection of pheS was carried out on MG medium containing 0.1% p-chlorophenylalanine (cPhe; dl-4-chlorophenylalanine from Acros Organics) as described previously (2). B. pseudomallei ΔasdBp::gat-FRT and ΔdapBBp::gat-FRT mutants were grown on rich LB medium plus 200 μg/ml DAP. For ΔdapBBp::gat-FRT mutants grown in minimal medium, MG medium plus 200 μg/ml DAP and 1 mM Lys was used; this minimal medium was also supplemented with 1 mM of both Met and Thr for growing ΔasdBp::gat-FRT mutants.

Molecular methods and reagents.

The oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table 3. All molecular methods and reagents used have been described previously (2).

TABLE 3.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Primer no. | Primer name | Sequencea |

|---|---|---|

| 557 | M13-RP | 5′-AGCGGATAACAATTTCACACAGGA-3′ |

| 558 | M13-FP | 5′-CGCCAGGGTTTTCCCAGTCACGAC-3′ |

| 715 | pPS854-XhoI | 5′-AAGCTCGAGCTAATTCC-3′ |

| 716 | pPS854-Cla-EcoRV | 5′-CAATATCGATATCCATTGCTGTTGACAAAG-3′ |

| 837 | PS12(cenocepacia) | 5′-ATCAGCCGTTGACTTAGTTGGTATTTCCGGAATATCATGCTGGTTCCGAATAATTTTGTTTAACTTTAAGAAGGAGATATACC-3′ |

| 849 | Tel-term-BamHI | 5′-TCGAGGATCCAGAAAGTCAAAAGCCTCCG-3′ |

| 876 | Tn7L | 5′-ATTAGCTTACGACGCTACACCC-3′ |

| 881 | bar-start | 5′CTTTAAGAAGGAGATATACCATGAGCCCAGAACGACGCC-3′ |

| 882 | bar-XhoI | 5′-GAAACTCGAGTCAAATCTCGGTGCCGGGCA-3′ |

| 892 | Bpasdup-HindIII | 5′-CGTCAAGCTTTCCCGGCCGTTGTG-3′ |

| 893 | Bpasddown-EcoRI | 5′-GTTGTGAATTCGTCGTAATCGCGTAG-3′ |

| 894 | gat-SacSDM | 5′-GCACTCGGAGCTTCAGGGGAAGAAGC-3′ |

| 1048 | dapB-up-XbaI | 5′-CGGCTCTAGAAGCCATGCAGGCGG-3′ |

| 1049 | dapB-up-nest | 5′-GAGCAGAACGACGCGAAC-3′ |

| 1050 | dapB-down-HindIII | 5′-CGAGAAGCTTGTACGCGAGCACCG-3′ |

| 1051 | dapB-down-nest | 5′-GAACGCGGTCATGATGAG-3′ |

| 1062 | 1026b-asd-up | 5′-CCCGAAAACGGGGTCCGT-3′ |

| 1063 | 1026b-asd-dn | 5′-CGACGCTTTCGGGTTGTGTA-3′ |

| 1070 | dapB-dn-out | 5′-CAGACGAACACGTGCAGATC-3′ |

| 1071 | dapBK9-upout-2 | 5′-AGCTCGATCTGCTCGCCGACAT-3′ |

| 1079 | glmS1-K9 | 5′-GAGGAGTGGGCGTCGATCAAC-3′ |

| 1080 | glmS2-K9 | 5′-ACACGACGCAAGAGCGGAATC-3′ |

| 1081 | glmS3-K9 | 5′-CGGACAGGTTCGCGCCATGC-3′ |

| 1117 | BpK9asd-upstrm-HindIII | 5′-GCGCGAAGCTTTCGACACGATG-3′ |

Restriction enzyme sites used in this study are underlined.

Conjugation into Burkholderia spp.

Conjugation between the E. coli strain E1354 and Burkholderia strains was routinely carried out as described previously (29) with the modifications described below. After conjugation, cells were resuspended and washed twice in 1 ml of 1× M9 buffer (to remove trace amino acids) and then resuspended in 1 ml of 1× M9 buffer; 100-μl and 200-μl aliquots of the cell suspensions were plated onto the appropriate media. Conjugation using this method usually resulted in 50 to 100 colonies for recombination of nonreplicating vectors when 100 μl of a 1-ml conjugation recovery culture was plated and 500 to 700 colonies for replicating plasmids when 100 μl of a 10× dilution was plated.

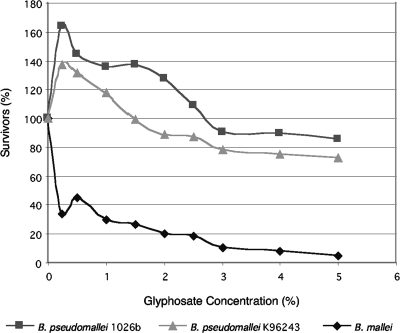

Growth inhibition of Burkholderia select-agent species in GS-containing medium after 24 h.

We wanted to determine if GS had a growth-inhibiting and killing effect by exposing B. pseudomallei strains 1026b and K96243 and B. mallei ATCC 23344 to increasing concentrations of GS for 24 h in minimal glucose medium. First, B. mallei and the two B. pseudomallei strains (1026b and K96243) were grown overnight in LB medium. The cultures were washed twice in 1 ml of 1× M9 buffer, resuspended in 1 ml of the same buffer, and used to inoculate (1:100 dilution) into 3 ml of MG medium plus 0.25%, 0.5%, 1.0%, 1.5%, 2.0%, 2.5%, 3.0%, 3.5%, or 4.0% GS with 30 μl of the washed cultures. Immediately, 100 μl of serial dilutions of each culture was plated to determine initial bacterial CFU/ml for each strain. After 24 h, 100 μl of serial dilutions from each culture was plated onto LB plates, and bacterial CFU/ml were again determined. We used the ratio of bacterial CFU/ml at 24 h to bacterial CFU/ml at the initial exposure to determine the percentage of survival after a 24-h exposure to GS (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Bacterial survival after incubation with different concentrations of GS for 24 h. B. mallei was more sensitive to GS than both B. pseudomallei strains, and killing of B. mallei by GS was observed at 0.25% GS. B. pseudomallei strain 1026b is significantly more resistant to GS than strain K96243. Minimal replication of both B. pseudomallei strains (less than doubling) after 24 h was observed at 0.25% GS. Killing was observed at 2% GS for strain K96243 and at 3% GS for strain 1026b.

Determination of GS MICs and GSECs.

To determine the MIC of GS in liquid medium, we first grew all strains overnight in LB medium. One milliliter of culture was harvested by centrifugation, washed twice in 1× M9 buffer to remove trace amounts of amino acids, resuspended in 1× M9 buffer, and diluted 100× in the same buffer. GS gradients in MG medium, starting with a concentration of 0.8% GS and decreasing by 2× dilutions to 0.00625% GS, were inoculated with 100× dilutions (∼105 CFU/ml) of each strain listed in Table 4. The MIC in liquid medium was then determined to be the concentration that showed no visible growth after 2 days of incubation, with shaking, at 37°C. To establish the MIC of GS on solid medium, we used MG medium plus GS and 1.5% (wt/vol) agar. Cultures of all species in LB medium were grown to an optical density at 600 nm of ∼0.8. One milliliter of each culture was harvested as described above for MICs in liquid medium and was resuspended in 1× M9 buffer. One hundred microliters of the high-cell-density cultures was then plated onto MG medium plates containing different concentrations of GS (ranging from 0 to 0.5%). The concentration at which no growth was observed after 2 weeks was defined as the plate MIC. The GS concentration for each species was increased by ∼30% above the MIC, and complete growth inhibition after 4 days in liquid medium and 3 weeks on solid medium was empirically taken as the effective concentration of GS (GSEC) (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

GSECs for Burkholderia species and E. coli

| Strain | GSEC (%) in:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Liquid mediuma | Solid mediumb | |

| B. cenocepacia | ||

| K56-2 | 0.32 | 0.5 |

| Bc7 | <0.005 | <0.005 |

| B. dolosa AUO158 | <0.005 | <0.005 |

| B. mallei ATCC 23344 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| B. pseudomallei | ||

| K96243 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| 1026b | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| B. thailandensis E264 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| E. coli K-12 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

Determined by the absence of growth after 4 days.

Determined by the absence of growth or spontaneously resistant colonies after 3 weeks.

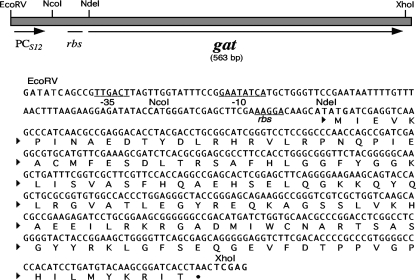

Engineering of pUC57-PS12-gat, pwFRT-PCS12-gat, and pBBR1MCS-2-PCS12-gat.

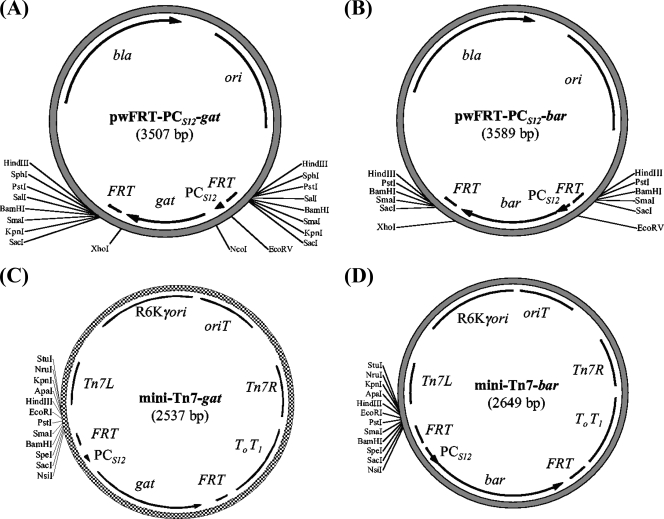

Driven by the B. pseudomallei rpsL promoter (PS12) (54), the gat gene sequence was optimized to the codon usage of B. pseudomallei. The gat gene sequence was synthesized by GenScript Corporation and was cloned into pUC57 as an EcoRV-XhoI fragment, yielding pUC57-PS12-gat. pUC57-PS12-gat was first digested with EcoRV and XhoI and was then inserted into EcoRV- and XhoI-digested pwFRT-Tpr, replacing the Tpr-cassette and yielding pwFRT-PS12-gat. We accidentally introduced a SacI restriction site during engineering, and it was removed by site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) using oligonucleotide 894 to yield pwFRT-PS12-gat-SDM. Additionally, the gat gene was initially engineered to be driven by PS12 on pUC57-PS12-gat. However, homologous recombination may occur with the PS12 region at the native locus on the chromosome or with an additional PS12 located on pBAKA. To prevent this possibility, the gat gene from pwFRT-PS12-gat-SDM was removed using NcoI and XhoI and was ligated into pwFRT-Telr cut with the same enzymes, replacing the Telr cassette with the gat gene, yielding pwFRT-PCS12-gat (Fig. 3 and 4A). Unique enzyme sites are present on the gat cassette to allow for ease of manipulation (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 3.

Schematic diagram of the engineered 563-bp gat gene on pwFRT-PCS12-gat. The B. cenocepacia rpsL promoter (PCS12) and ribosomal binding site (rbs) are shown in relation to the gat gene. Below the schematic are the corresponding nucleotide and protein sequences. Codons were optimized according to the codon preference within the B. pseudomallei K96243 asd gene. Also indicated are the −35 and −10 regions of the PCS12 promoter. Restriction sites (in boldface) were positioned strategically for subsequent cloning and manipulation.

FIG. 4.

Maps of pwFRT-PCS12-gat (A), pwFRT-PCS12-bar (B), mini-Tn7-gat (C), and mini-Tn7-bar (D). (A) pwFRT-PCS12-gat is flanked with symmetrical restriction-sites (HindIII to SacI) that will cut to remove the gat cassette flanked with identical wild-type FRT sequences. Not shown are four other FRT-gat cassettes with unique flanking FRT-sequences (pmFRT-gat, pFRT1-gat, pFRT2-gat, and pFRT3-gat), where the gat marker is flanked by identical FRTs with unique spacer sequences. The DNA sequences and restriction sites for all five gat-FRT cassettes are identical with the exception of the spacers. (B) pwFRT-PCS12-bar, with bar flanked by wild-type FRT sequences and symmetrical restriction enzyme sites. (C and D) mini-Tn7-gat (C) and mini-Tn7-bar (D) were engineered to allow site-specific integration of the cloned gene(s), using the non-antibiotic resistance bar or gat selectable marker, with the assistance of a helper plasmid (pTNS3-asdEc). bla, β-lactamase-encoding gene; ori, ColE1 origin of replication; oriT, conjugal origin of transfer; R6Kγori, π protein-dependent R6K origin of replication; Tn7L and Tn7R, left and right transposase recognition sequences; T0T1, transcriptional terminator.

pBBR1MCS-2-PCS12-gat was constructed to test the effectiveness of GS selection in E. coli and B. thailandensis by comparing colony numbers on LB-plus-Km medium with those on MG-plus-GS medium. pBBR1MCS-2 was digested with KpnI, blunt ended, and then digested with XhoI. The resultant fragment was ligated to the 563-bp EcoRV-XhoI PCS12-gat fragment from pwFRT-PCS12-gat, yielding pBBR1MCS-2-PCS12-gat.

Determination of the PPTEC and construction of pBBR1MCS-2-PCS12-bar.

The effective concentration of PPT (PPTEC) from the herbicide Finale was determined in the same manner as the GSEC. We first determined whether bar would be an efficient selectable marker in E. coli and B. thailandensis by constructing pBBR1MCS-2-PCS12-bar. The bar gene was amplified from pCAMBIA-1301-bar using oligonucleotides 881 and 882. The product was then used as a template for a second PCR using oligonucleotides 837 and 882 to introduce the B. cenocepacia rpsL promoter (PCS12). The 800-bp PCR product was then digested with XhoI and ligated into EcoRV- and XhoI-digested pBBR1MCS-2 to yield pBBR1MCS-2-PCS12-bar. This construct was then introduced into E. coli and subsequently into B. thailandensis via electroporation. The PPTECs were determined to be 0.3% and 1.5% for E. coli and B. thailandensis, respectively. Introduction of pBBR1MCS-2-PCS12-bar into E. coli and B. thailandensis yielded the same number of colonies on kanamycin-containing medium as on PPT-containing medium (data not shown), indicating that this source of PPT contains no other ingredients that could adversely affect the selection of bar-containing constructs. The PPTECs for B. pseudomallei 1026b, B. pseudomallei K96243, and B. mallei were found to be 2.5% by the methods described above for the GSEC.

Construction of gat-FRT and bar-FRT vectors.

Using pwFRT-PCS12-gat with TCTAGAAA as the wild-type spacer of the flanking FRT sequences, we also constructed four other plasmids based on four other unique FRT sequences: pmFRT-PCS12-gat, with the flanking FRT spacer TGTAGATA; pFRT1-PCS12-gat, with a TCTTGAAA spacer; pFRT2-PCS12-gat, with a TCTAGGAA spacer; and pFRT3-PCS12-gat, with a TCTCGAAA spacer. The differences in the spacer sequence yield unique FRTs. The unique FRTs in these five plasmids (pwFRT-PCS12-gat, pmFRT-PCS12-gat, pFRT1-PCS12-gat, pFRT2-PCS12-gat, and pFRT3-PCS12-gat) allow for multiple rounds of allelic replacement by recycling the same marker with Flp-FRT excision, reducing the risk of chromosomal deletions and rearrangements as observed previously (1). To construct these four plasmids, laboratory vectors pmFRT-Gmr, pFRT1-Gmr, pFRT2-Gmr, and pFRT3-Gmr were PCR amplified with oligonucleotides 715 and 716 to produce plasmid backbones without the Gmr marker. Each plasmid backbone was digested with EcoRV and XhoI and was ligated with the PCS12-gat fragment obtained from pwFRT-PCS12-gat by EcoRV and XhoI digestion. Essentially, the sequences of all four new pFRT-PCS12-gat-FRT plasmids are the same as that of pwFRT-PCS12-gat, with the exception of the FRT spacer sequences flanking the gat cassette. The FRT-flanked bar cassette on pwFRT-PCS12-bar was constructed by first amplifying the bar gene from pCAMBIA-1301-bar via a two-step PCR, as described above for the construction of pBBRMCS1-2-PCS12-bar. The 800-bp bar fragment was digested with XhoI and ligated into EcoRV- and XhoI-digested pwFRT-PCS12-Telr, replacing the Telr-cassette with the bar gene to produce pwFRT-PCS12-bar.

Construction of pBAKA-ΔasdBp::gat-FRT and pBAKA-ΔdapBBp::gat-FRT.

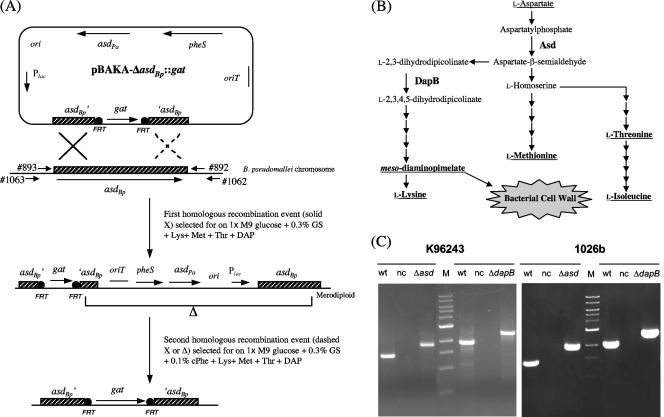

The B. pseudomallei K96243 asd gene was amplified from chromosomal DNA using oligonucleotides 892 and 893. This asdBp gene sequence is essentially identical for K96243 and 1026b. The 1.4-kb fragment was digested with EcoRI and HindIII and was cloned into pUC18 digested with the same enzymes. After cloning, the purified plasmid, pUC18-asdBp, was electroporated into the dam-negative strain GM33. Plasmids were isolated, digested with BclI (dam methylation sensitive) and EcoRV, and blunt ended. The plasmid backbone was then ligated to the 0.7-kb fragment from SmaI-digested pwFRT-PCS12-gat, resulting in a 250-bp deletion in the asdBp gene. pUC18-ΔasdBp::gat-FRT was then digested with EcoRI and HindIII, and the 1.9-kb fragment was cloned into pBAKA, cut with the same enzymes, to produce pBAKA-ΔasdBp::gat-FRT. The gat gene is in the same orientation as the asdBp gene (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 5.

(A) Gene replacement strategy using a gat-FRT cassette to inactivate the B. pseudomallei strain K96243 and 1026b asdBp genes. Oligonucleotides 892 and 893 were used in the initial cloning of the asdBp gene into the allelic-replacement vector pBAKA, and the asdBp gene was inactivated with the gat-FRT cassette. Deletion of the chromosomal asdBp gene with pBAKA-ΔasdBp::gat was performed as shown. PCR verification of the ΔasdBp mutant was done using outside oligonucleotides 1062 and 1063. The asdBp genes of both the K96243 and the 1026b strain were inactivated using pBAKA and pheS for counterselection. Similarly, the dapBBp gene of strain K96243 was inactivated using pBAKA and pheS for counterselection (not shown) (see Materials and Methods). Oligonucleotides 1049 and 1051 were used to amplify the ΔdapBBp::gat cassette from plasmid pBAKA-ΔdapBBp::gat in order to inactivate the dapBBp gene from strain 1026b using the DNA incubation method (46) (see Materials and Methods). (B) Bacterial amino acid biosynthetic pathway of the aspartate family, where aspartate is used to synthesize DAP, Lys, Met, Thr, and Ile. The indicated reactions catalyzed by Asd and DapB are central to this pathway, and mutants of these genes cannot cross-link their cell walls due to the lack of DAP. (C) PCR verification of the ΔasdBp and ΔdapBBp mutants. In each case, as expected, the PCR products indicated that the chromosomal fragment of the mutant is larger than that of the wild type (wt), and the no-template negative control (nc) showed no PCR product. asdBp, B. pseudomallei asd gene encoding aspartate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase; asdPa, P. aeruginosa asd gene; dapBBp, B. pseudomallei gene encoding dihydrodipicolinate reductase; M, 1-kb ladder (New England Biolabs); Plac, lac promoter; pheS, mutant B. pseudomallei gene encoding the α subunit of phenylalanyl tRNA synthase.

To construct pBAKA-ΔdapBBp::gat-FRT, the B. pseudomallei K96243 dapB gene was amplified from chromosomal DNA using oligonucleotides 1048 and 1050. The 1.9-kb fragment was digested with HindIII and XbaI and was ligated into pBAKA cut with the same enzymes. pBAKA-dapBBp was then digested with SalI and ligated with the 0.7-kb fragment from the SalI digestion of pwFRT-PCS12-gat, producing pBAKA-ΔdapBBp::gat-FRT. The gat gene is in the opposite orientation to the dapBBp gene.

Engineering of B. pseudomallei ΔasdBp::gat-FRT and ΔdapBBp::gat-FRT mutants.

E1354 was utilized as the conjugal donor to introduce the allelic-replacement vectors, pBAKA-ΔasdBp::FRT-gat and pBAKA-ΔdapBBp::gat-FRT, into B. pseudomallei strain K96243. Conjugations were carried out as described above, and 100 μl and 200 μl of the conjugation mixtures were plated onto MG medium plus 200 μg/ml DAP, 0.3% GS, and 1 mM (each) Lys, Met, and Thr; these last 3 amino acids (3AA) and DAP are required for the specific Δasd mutation (Fig. 5B). Colonies appearing after 3 to 4 days were streaked out on the same medium supplemented with 0.1% cPhe to counterselect against pheS. It is critical for clean counterselection that the medium, in the presence of cPhe, contain no competing phenylalanine, as previously described (2). GS-resistant mutants were screened by patching with toothpicks onto plates with and without DAP (MG medium plus 0.3% GS, 0.1% cPhe, and 1 mM 3AA, with or without 200 μg/ml DAP). Mutants unable to grow without DAP were purified once on LB medium plus DAP and were patched again on MG medium plus 0.3% GS, 0.1% cPhe, and 1 mM 3AA, with or without 200 μg/ml DAP, for confirmation. Purification from potential background on LB medium plus DAP is recommended and is very important, because GS is bacteriostatic, rather than bactericidal, at this effective concentration. Further screening and confirmation of DAP-requiring mutants were performed by PCR using oligonucleotides 1062 and 1063, which annealed to the chromosome outside of the region cloned for allelic replacement (Fig. 5A and C).

To engineer the B. pseudomallei K96243 ΔdapBBp::gat-FRT mutant, the methodologies were essentially the same as for the engineering of ΔasdBp::gat-FRT, except that only 1 mM Lys was added to the medium with DAP rather than the 3AA (Fig. 5B). DAP-requiring colonies were further purified as described above on LB medium plus DAP, because GS is a bacteriostatic agent. ΔdapBBp mutants were screened by PCR using oligonucleotides 1070 and 1071, which anneal outside of the oligonucleotides used for cloning (Fig. 5C).

For B. pseudomallei strain 1026b, we engineered and confirmed the ΔasdBp mutant essentially as described above for strain K96243, via counterselection with cPhe/pheS. To demonstrate that the DNA incubation approach also works by using gat for selection with GS in strain 1026b, we used the published DNA incubation and natural transformation approach to delete the dapBBp gene in strain 1026b (46). pBAKA-ΔdapBBp::gat-FRT was used as a template along with oligonucleotides 1049 and 1051 in a PCR to obtain a linear 2.7-kb ΔdapBBp::gat-FRT fragment. Allelic replacement was performed as previously published (2), but selection was carried out on MG medium plus 0.3% GS, 200 μg/ml DAP, and 1 mM Lys. GS-resistant colonies that required DAP were purified and further confirmed by PCR with oligonucleotides 1070 and 1071 as described above.

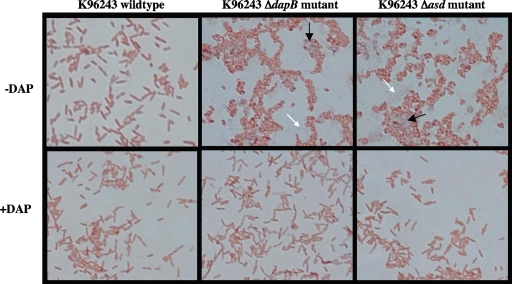

Phenotypic lysis of Δasd and ΔdapB mutants without DAP.

The B. pseudomallei wild-type strain K96243, the K96243 ΔasdBp::gat-FRT mutant, and the K96243 ΔdapBBp::gat-FRT mutant were first grown overnight in LB medium alone (wild-type strain) or LB medium plus DAP (ΔasdBp::gat-FRT and ΔdapBBp::gat-FRT strains). One milliliter of each culture was centrifuged, and cell pellets were washed twice with LS (LB-no-salt) medium and resuspended in 20 μl of LS. Ten microliters of each concentrated cell resuspension was spotted onto LS plates and LS-plus-DAP plates and was incubated at 37°C. After 18 h, cells were resuspended in sterile saline (0.85% NaCl) and smeared onto glass slides. The slides were then air dried and fixed with 1% paraformalydehyde (in phosphate-buffered saline) for 1 h. This fixing method was initially tested on wild-type K96243, and the slide was incubated in rich LB medium for 3 weeks to ensure that no growth was observed, indicating complete killing. Finally, the cells were stained with safranin for 10 min, gently rinsed with water, and examined under an 100× oil immersion objective lens (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Phenotypic characterization of B. pseudomallei K96243 ΔasdBp and ΔdapBBp mutants. Wild-type K96243 was rod shaped when grown in the absence or presence of DAP (left). The ΔasdBp (center) and ΔdapBBp (right) mutant strains grow, but “pop and die” without the ability to cross-link their cell walls in the absence of DAP. The majority of the bacteria are in the process of forming protoplasts. Some protoplasts could be observed (black arrows), as well as cell debris (white arrows) due to bacterial lysis; these were absent when mutants were grown in the presence of DAP (bottom).

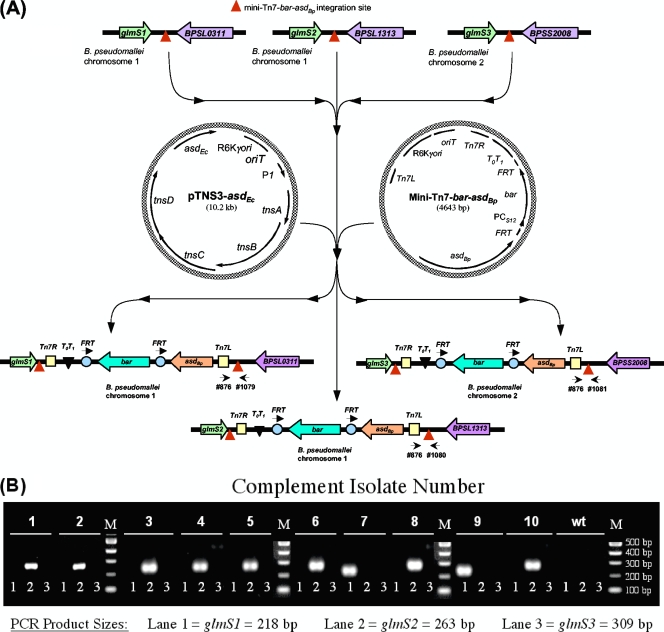

Construction of mini-Tn7-bar and mini-Tn7-bar-asdBp.

To construct the site-specific mini-Tn7-bar transposon, mini-Tn7-Telr was digested with XbaI (cut in the flanking FRT spacer regions), and the bar cassette from pwFRT-PCS12-bar (also digested with XbaI in the FRT spacer regions) was ligated to replace the Telr cassette. Recovery of the FRT sequences was verified by confirming the orientation of the cloned PCS12-bar fragment, and recovery of the XbaI sites was verified via restriction enzyme digestions. To construct mini-Tn7-bar-asdBp, the asdBp gene with 600 bp of upstream sequence was amplified from the B. pseudomallei K96243 chromosome to include the putative promoter. The 1.8-kb asdBp gene was PCR amplified from K96243 chromosomal DNA using oligonucleotides 893 and 1117, and the product was digested with EcoRI and HindIII. mini-Tn7-bar was digested with the same enzymes and ligated to this 1.8-kb asdBp gene, resulting in mini-Tn7-bar-asdBp. The asdBp gene was cloned in the same orientation as the bar cassette. The functionality of the asdBp gene was verified by transformation into a Δasd E. coli strain (E1345); growth was observed on LB medium in the absence of DAP.

Complementation of the B. pseudomallei ΔasdBp::gat-FRT mutant.

The B. pseudomallei 1026b ΔasdBp::gat-FRT mutant was complemented using the mini-Tn7-bar-asdBp vector. The mini-Tn7-bar-asdBp vector and its helper plasmid (pTNS3-asdEc) were transformed individually into E. coli E1354 (a conjugation-proficient tryptophan auxotroph) and conjugated into B. pseudomallei ΔasdBp::gat-FRT in a triparental mating experiment. Conjugation mixtures were resuspended in 1 ml of 1× M9 minimal medium, and 100 μl of a 1:10 dilution was plated on MG medium plus 200 μg/ml DAP, 2.5% PPT, and 1 mM (each) Lys, Met, and Thr. This medium prevents the E. coli donor (Trp auxotroph) from growing and selects for PPT-resistant B. pseudomallei. Ten isolates were screened for positive integration using oligonucleotide 876, which anneals in the Tn7L region of the mini-Tn7-bar site-specific transposon, and oligonucleotide 1079, 1080, or 1081, each of which is specific for one of the three possible integration sites on the chromosome (10). Two positive isolates with insertions at glmS1 and three isolates with insertions at glmS2 were chosen for further characterization (below).

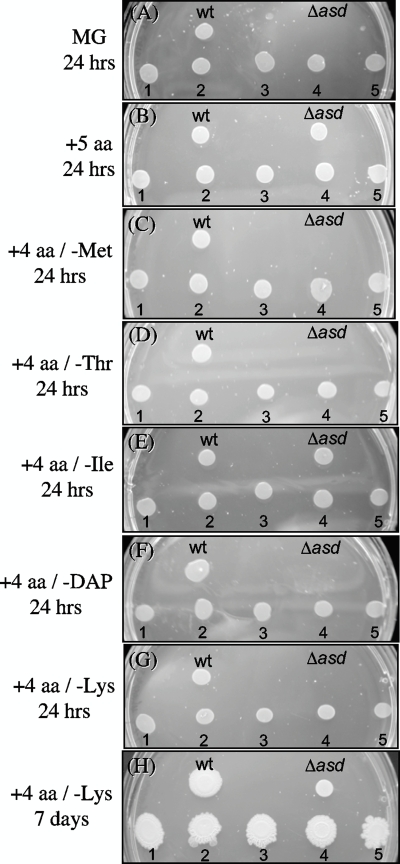

Growth of wild-type B. pseudomallei strain 1026b, its ΔasdBp::gat-FRT mutant, and ΔasdBp::gat-FRT/attTn7-bar-asdBp complemented isolates.

To further characterize the Δasd mutation, we first grew strain 1026b, the ΔasdBp mutant strain, and several complemented strains overnight in LB medium plus DAP at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm. One milliliter of each culture was harvested by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 2 min. The pellet was washed twice with 1× M9 buffer to remove any residual nutrients and was resuspended in 1 ml of 1× M9 buffer. To determine the amino acid auxotrophic properties of these strains, the cell suspensions were diluted 20× in 1× M9 buffer. Five microliters of each culture was spotted onto plates with MG medium plus 200 μg/ml DAP and 1 mM (each) Ile, Lys, Met, and Thr; the same amount of diluted culture was spotted onto five other plates, each missing one of the four amino acids or DAP. Growth on the plates was observed after 24 h and 7 days (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Growth characteristics of the B. pseudomallei K96243 ΔasdBp mutant and five complemented isolates relative to that of the wild type (wt) on medium lacking amino acids (aa) of the aspartate family. (A) On 1× MG medium, the ΔasdBp mutant did not grow compared to the wt, whereas five strains (numbered 1 to 5) complemented using the mini-Tn7-bar-asdBp transposon all grew as well as the wt. Spots 1 and 2 are Tn7-bar-asdBp-complemented isolates transposed at the glmS1 site, while spots 3 to 5 are complemented isolates transposed at the glmS2 site. (B) The ΔasdBp mutant grew similarly to the wt on MG medium when provided with all five aa of the aspartate family (DAP, Lys, Met, Thr, and Ile). (C through F) The ΔasdBp mutant could not grow when four of the five aa were present in the MG medium and only Met (C), Thr (D), or DAP (F) was omitted, whereas the wt and all complemented strains grew well on these media. The ΔasdBp mutant still grew when Ile was omitted from MG medium containing the other four aa (E), because Thr in the medium could be converted to Ile in this pathway. (G) Surprisingly, no growth was observed when Lys was omitted from the MG medium supplemented with four aa (Met, Thr, DAP, and Ile). We suspect that the amount of DAP provided was shuffled for use in cell wall biosynthesis and that very little was converted to Lys for growth. The ΔasdBp mutant grew slowly on this medium. (H) When the plate in panel G was incubated for another 6 days, growth was observed for the ΔasdBp mutant, indicating that some DAP did get converted to Lys. All other plates on which the ΔasdBp mutant did not grow after 1 day also did not show growth of this mutant after 7 days (data not shown).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences of all constructs shown in Fig. 4 were submitted to GenBank. The accession numbers are FJ384986 for pwFRT-PCS12-gat, FJ858786 for pwFRT-PCS12-bar, FJ858785 for mini-Tn7-gat, and FJ826509 for mini-Tn7-bar.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Effectiveness of GS against Burkholderia species.

Although studies have measured the inhibitory concentrations of GS for P. aeruginosa, E. coli, B. subtilis, and B. japonicum (16, 55), no studies have determined the GS inhibitory concentrations for Burkholderia species. It was previously shown that growth inhibition of B. japonicum was observed at a lower GS concentration (5 mM, or 0.085%) and that rapid death occurred at a higher GS concentration (10 mM, or 0.17%) (55). Thus, GS could be bactericidal depending on the concentration used. We initially determined the inhibitory or killing action of GS for three Burkholderia select-agent strains (Fig. 2). When exposed to different concentrations of GS for 24 h, B. mallei was found to be more sensitive to GS than B. pseudomallei, and >60% death was observed upon exposure to a concentration as low as 0.25%. Clearly, compared to the high cell density following overnight incubation in the absence of GS, no significant replication beyond doubling was observed at concentrations as low as 0.25% GS. Both B. pseudomallei strains replicated to slightly less than double their original number at 0.25% GS and were killed at higher concentrations of GS (Fig. 2), probably because of residual intracellular aromatic amino acid levels after growth in LB medium prior to GS exposure. Although the mechanism of GS inhibition of Burkholderia species is to be determined in future studies, it is likely similar to the mechanism of EPSPS inhibition in plants, which has been confirmed for P. aeruginosa, E. coli, B. subtilis, and B. japonicum (16, 55).

We next wanted to determine the MICs of GS for members of the Burkholderia genus before empirically identifying the GSECs in liquid and on solid media (see Materials and Methods). Significantly high cell densities, typical in genetic manipulations (e.g., 105 CFU was added to liquid medium and 100 μl of ∼109 CFU/ml was plated onto solid medium containing different concentrations of GS), were inoculated to determine the MIC of GS as the concentration at which no growth was observed after 2 days (liquid medium) or at which no spontaneously resistant colonies arose after 2 weeks (solid medium). The GSEC above the GS MIC was defined and utilized to ensure no growth of high inocula in liquid medium after 4 days or no growth for 3 weeks on solid medium (Table 4). We determined the GSEC within this time frame for liquid and solid media, because this period is sufficient to observe most mutants that will arise during allelic replacement and also allows most Burkholderia species to grow on minimal medium during selection. The GSECs for E. coli and for B. pseudomallei, B. mallei, and B. cenocepacia K56-2 are higher than those for other Burkholderia species (Table 4). We have utilized the GSEC in Table 4 to select for the gat gene (see below) successfully in E. coli, B. thailandensis, and the two wild-type B. pseudomallei strains. Thus, we are confident that the GSECs for other species in Table 4 are appropriate.

Roundup is an appropriate source of GS for selection. We have not encountered any problem with the solubility of GS at high concentrations (10% was the highest concentration tested using purified GS). Indeed, the “superconcentrated” Roundup that we purchased contained 50% GS in aqueous solution. In addition to this advantage, GS is readily available, inexpensive, relatively nontoxic, and not in clinical use, and it gives tight selection (see below). Although purified GS could be purchased from Sigma and other distributors, we do not have concerns with using Roundup for selection, since purified GS gave the same GSEC (data not shown). One bottle of “superconcentrated” Roundup purchased from a local garden supply store has lasted for the duration of this study. Roundup formulations with lower concentrations of GS are also available, although we recommend the “superconcentrated” Roundup, because it is potent enough for >150 liters of culture when used at a final concentration of 0.3%. Selection of pBBR1MCS-2-PCS12-gat (kanamycin and GS resistance) in E. coli and B. thailandensis on kanamycin or on GS from Roundup yielded the same number of colonies (data not shown), providing evidence that Roundup is appropriate for selection. This indicates that no other ingredient(s) in Roundup has adverse effects on the selection of gat-containing constructs and that this source of GS is appropriate for selective media.

Engineering of a gat cassette and effective selection with GS.

We engineered the gat gene through GenScript Corporation, based on the previously described GAT protein sequences (5), using an approach similar to that for the synthesis of the pheS gene (2). We utilized this approach to optimize the codon usage for efficient expression in Burkholderia species, while eliminating many restriction sites within the gene and strategically placing others at certain locations for future manipulation. The engineered gat cassette, including the B. cenocepacia promoter of the rpsL gene (PCS12), is only 563 bp (Fig. 3). The small size of the gat cassette makes it easy to manipulate, clone, and amplify by PCR for use in the DNA incubation method of allelic replacement in naturally competent Burkholderia species (46). As proof of concept, we utilized this cassette in the DNA incubation approach to delete the asd gene of B. thailandensis (asdBt) at its GSEC (data not shown). This confirmed that the GSECs in Table 4 are sufficient for selection.

Deletional mutagenesis of the essential asdBp and dapBBp genes using GS and gat.

The reliability of any marker for mutagenesis would best be demonstrated by the successful mutagenesis of essential genes. Therefore, we chose two essential genes, asd and dapB, that are absolutely required for DAP synthesis and cell wall cross-linking in most gram-negative bacteria (Fig. 5B) (8, 11, 20, 22, 37). Mutation of the asd gene makes gram-negative bacteria auxotrophic for three amino acids (Thr, Met, DAP), while dapB mutants require only DAP. Although Lys and Ile are also made from the same pathway, the DAP and Thr provided should act as precursors for Lys and Ile biosynthesis, respectively (Fig. 5B). The asdBp and dapBBp genes encode aspartate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase (BPSS1704 on chromosome 2) and a dihydrodipicolinate reductase (BPSL2941 on chromosome 1), respectively.

To knock out the asdBp and dapBBp genes, we engineered gat-FRT cassettes for allelic replacement (Fig. 4A). As mentioned above, a gat-FRT cassette was successfully utilized to delete the asdBt gene using the DNA incubation and natural transformation method (46), where selection with 0.04% GS yielded ΔasdBt mutation frequencies of ∼80% (data not shown). We then utilized pBAKA and the pheS counterselection approach as previously described (2), with the gat-FRT cassette from pwFRT-PCS12-gat, to inactivate the asdBp and dapBBp genes in B. pseudomallei (Fig. 4A and 5A). Independent merodiploids resulting from the first recombination in strain K96243 were obtained with 0.3% GS after 3 days of growth (see Materials and Methods). Streaking of merodiploids onto medium containing 0.1% cPhe and 0.3% GS for counterselection to resolve the mutations yielded DAP-requiring colonies at frequencies of ∼25% and ∼80% for the B. pseudomallei K96243 Δasd and ΔdapB mutants, respectively. To demonstrate this principle of allelic replacement with another B. pseudomallei strain, we utilized the same approach with cPhe/pheS counterselection to create a 1026b ΔasdBp mutant, which yielded a lower mutation frequency of ∼10% for this essential gene. Since strain 1026b is also naturally competent, we wanted to utilize the published DNA incubation method for allelic replacement (46) by engineering a ΔdapBBp mutant, yielding 1026b ΔdapBBp mutants at a frequency of ∼25%. We confirmed these mutations by PCR with oligonucleotides annealing to chromosomal regions outside of the initial primers used for cloning (Fig. 5A and C). Because GS is bacteriostatic at the concentration used (Table 4 and Fig. 2), it is critical to purify all mutants from the potential background contamination before reconfirmation of the phenotype, PCR confirmation, and growth for long-term storage at −80°C. Phenotypically, ΔdapBBp mutants required DAP for growth (data not shown), while ΔasdBp mutants required DAP, Thr, and Met (Fig. 7). Using wild-type strain K96243 and its mutants as examples, we further characterized the phenotypes of ΔasdBp and ΔdapBBp mutants. In the presence of DAP, both ΔasdBp and ΔdapBBp mutants displayed a normal rod-shaped cellular morphology (Fig. 6). However, in the absence of DAP, these two mutants, lacking DAP for cell wall biosynthesis and cross-linking, showed “cell-rounding” characteristics and evidence of lysis (Fig. 6).

ΔasdBp mutant complementation with a site-specific mini-Tn7-bar-asdBp transposon.

We engineered a site-specific transposon based on mini-Tn7, which has previously been demonstrated to integrate at three possible glmS sites in the B. pseudomallei chromosome (10) (Fig. 4D and 8A). Our construct, mini-Tn7-bar, is based on the nonantibiotic bar gene, which encodes resistance to bialaphos and PPT (a bialaphos degradation product also known as glufosinate). Since bialaphos can be very expensive, a cheaper alternative, PPT, can be used. We determined the PPTECs for B. mallei and B. pseudomallei to be ∼2.5%. Many herbicide brands (e.g., Basta, Buster, Dash, Finale, Hayabusa, Ignite, Conquest, Liberty, Rely, Shield, Harvest, Sweep, and Arise) contain PPT as the active ingredient. Since the PPTEC is quite high, we picked the herbicide Finale, because it contains the highest PPT concentration (11.33%, wt/vol) we could find, although other brands not available on our island (e.g., Liberty and Ignite) can contain 20 to 25% PPT. In this study, we utilized the 11.33% PPT in Finale as the working stock to make media at the 2.5% PPTEC. As proof of concept, we introduced the mini-Tn7-bar-asdBp construct into the B. pseudomallei 1026b ΔasdBp strain to complement the ΔasdBp mutation. The suicidal helper plasmid pTNS3-asdEc, harboring the E. coli asd (asdEc) gene for maintenance in an E. coli Δasd strain, aids the transposition of the Tn7-bar-asdBp transposon to one of three possible glmS chromosomal targets (Fig. 8A). We selected PPT-resistant colonies in the presence of DAP, Lys, Met, and Thr to prevent bias in immediately selecting for complemented strains. After colonies were patched onto DAP-supplemented medium, it was found that ∼64% of PPT-resistant colonies tested (45 out of 70) had been complemented and did not require DAP, while the remaining ∼36% were probably spontaneously PPT resistant colonies. It was further confirmed that the majority of the complemented isolates (8 out of 10 tested) had mini-Tn7-bar-asdBp transposed to the region downstream of the glmS2 target, while 2 out of 10 recombined at the glmS1 target (Fig. 8B). No transposition at the glmS3 target was observed. These data indicated that the PPT in Finale was appropriate for selection of the bar gene and yielded a fairly high frequency of transposition.

FIG. 8.

Single-copy complementation of the B. pseudomallei 1026b ΔasdBp mutant using mini-Tn7-bar-asdBp. (A) The suicidal plasmid mini-Tn7-bar-asdBp and its suicidal helper plasmid, pTNS3-asdEc, were introduced into the B. pseudomallei 1026b ΔasdBp mutant by conjugation. Tn7 has three possible integration sites on different chromosomes (indicated by red triangles), as previously described (10), which can result in complementation of the ΔasdBp mutation from three different chromosomal loci, as depicted according to the annotation of B. pseudomallei strain K96243. Ten random complemented isolates were screened using oligonucleotide Tn7L (876) and an oligonucleotide specific for each potential integration site (oligonucleotide 1079, 1080, or 1081), as indicated by arrows. (B) For each isolate, PCR verification of 10 random complemented isolates was performed for all three glmS sites (lanes 1, 2, and 3). Insertion downstream of glmS1 would result in a 218-bp PCR product; insertion downstream of glmS2 would result in a 263-bp fragment; and insertion downstream of glmS3 would result in a 309-bp PCR product. Isolates 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, and 10 had Tn7 inserted downstream of glmS2. Isolates 7 and 9 showed PCR products near 200 bp, indicating Tn7 integration downstream of glmS1. P1, P1 integron promoter; glmS1, glmS2, and glmS3 encode three different B. pseudomallei glucosamine 6-phosphate synthetases; M, 100-bp ladder (New England Biolabs); tnsABCD, Tn7 transposase-encoding genes.

To further characterize five complemented isolates along with the wild-type strain 1026b and the ΔasdBp mutant, we spotted these strains onto various media lacking one of the five amino acids (DAP, Lys, Met, Thr, or Ile) in the aspartate family of amino acid biosynthetic pathways. Media lacking Met, Thr, or DAP yielded no growth of the ΔasdBp mutant compared to the growth of the wild-type strain 1026b and the five complemented strains, confirming that the Asd reaction gives rise to these amino acids (Fig. 5B and 7). Ile and Lys were not required by the ΔasdBp mutant, since Thr and DAP will yield Ile and Lys, respectively (Fig. 7E and H). In summary, the Δasd mutant of B. pseudomallei displayed a phenotype similar to those of asd mutants of other gram-negative bacteria, and the successful complementation of this mutant suggests that our allelic-replacement approach did not introduce any undesirable mutations by selection with Roundup and Finale.

Conclusions.

(i) We engineered and successfully demonstrated the use of a novel non-antibiotic resistance gat marker, based on resistance to GS, in Burkholderia species. This cassette was demonstrated to be useful for allelic replacement of essential genes in B. pseudomallei, adding valuably to the limited number of select-agent approved markers. The advantages of using GS-containing herbicides to select for the gat cassette in recombinant work include cost-effectiveness, availability, low toxicity, no clinical use, high solubility, relatively tight selection, and the small size of the gat marker. The gat cassette was used successfully in more than one allelic-replacement strategy to delete two essential genes, confirming its value, the usefulness of pheS as a counterselectable marker, and compatibility with the DNA incubation method for naturally competent Burkholderia species (46). (ii) We initiated the successful utilization of a second non-antibiotic resistance marker, based on the better-characterized bar gene (49), encoding bialaphos and PPT (glufosinate) resistance. This will hopefully also expand the future use of this marker for select-agent species. One minor disadvantage of using gat and bar is the requirement for minimal media lacking two of the three aromatic amino acids (Phe, Tyr, or Trp) and glutamine, respectively. Therefore, for most mutations, the use of 1× M9 medium plus 20 mM glucose should suffice for B. pseudomallei, B. mallei, and B. thailandensis. Note that we added DAP, Lys, Met, and Thr to the media in this study, because of mutant-specific amino acid requirements (e.g., ΔasdBp and ΔdapBBp). (iii) We created two mutants in two wild-type B. pseudomallei strains, which may be promising as future attenuated vaccine candidates, since DAP is a bacterium-specific product not available in mammalian hosts. (iv) Finally, it should be noted that all genetic tools used in this study are completely devoid of antibiotic resistance during introduction and selection. The potential use of gat and bar may be expanded to other select-agent species (e.g., Brucella and Francisella spp.), since minimal media lacking Phe, Tyr, Trp, and Gln have been defined for some of these species (6, 18). GS and PPT, compounds originally designed to kill plant weeds, may prove quite useful for the future selection of recombinants in bacterial select-agent species.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R21-AI074608 to T.T.H. A graduate stipend for M.H.N. was supported by an NSF IGERT award (0549514) to B.A.W.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 31 July 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barekzi, N., K. L. Beinlich, T. T. Hoang, X.-Q. Pham, R. R. Karkhoff-Schweizer, and H. P. Schweizer. 2000. The oriC-containing region of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa chromosome undergoes large inversions at high frequency. J. Bacteriol. 182:7070-7074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrett, A. R., Y. Kang, K. S. Inamasu, M. S. Son, J. M. Vukovich, and T. T. Hoang. 2008. Genetic tools for allelic replacement in Burkholderia species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:4498-4508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borgherini, G., P. Poubeau, F. Paganin, S. Picot, A. Michault, F. Thibault, and C. A. Berod. 2006. Melioidosis: an imported case from Madagascar. J. Travel Med. 13:318-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brett, P. J., D. DeShazer, and D. E. Woods. 1998. Burkholderia thailandensis sp. nov., a Burkholderia pseudomallei-like species. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 48:317-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castle, L. A., D. L. Siehl, R. Gorton, P. A. Patten, Y. H. Chen, S. Bertain, H.-J. Cho, N. Duck, J. Wong, D. Liu, and M. W. Lassner. 2004. Discovery and directed evolution of a glyphosate tolerance gene. Science 304:1151-1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chamberlain, R. E. 1965. Evaluation of live tularemia vaccine prepared in a chemically defined medium. Appl. Microbiol. 13:232-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan, Y. Y., and K. L. Chua. 2005. The Burkholderia pseudomallei BpeAB-OprB efflux pump: expression and impact on quorum sensing and virulence. J. Bacteriol. 187:4707-4719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, N. Y., S. Q. Jiang, D. A. Klein, and H. Paulus. 1993. Organization and nucleotide sequence of the Bacillus subtilis diaminopimelate operon, a cluster of genes encoding the first three enzymes of diaminopimelate synthesis and dipicinolate synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 268:9448-9465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng, A. C., and B. J. Currie. 2005. Melioidosis: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Clin. Microbiol. 18:383-416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi, K. H., T. Mima, Y. Casart, D. Rholl, A. Kumar, I. R. Beacham, and H. P. Schweizer. 2008. Genetic tools for select-agent-compliant manipulation of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:1064-1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cirillo, J. D., T. R. Weisbrod, L. Pascopella, B. R. Bloom, and W. R. Jacob, Jr. 1994. Isolation and characterization of the aspartokinase and aspartate semialdehyde dehydrogenase operon from mycobacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 11:629-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dance, D. A. B. 1991. Melioidosis: the tip of the iceberg? Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 4:52-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeShazer, D., P. J. Brett, R. Carlyon, and D. E. Woods. 1997. Mutagenesis of Burkholderia pseudomallei with Tn5-OT182: isolation of motility mutants and molecular characterization of the flagellin structural gene. J. Bacteriol. 179:2116-2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dill, G. M. 2005. Glyphosate-resistance crops: history, status, and future. Pest Manag. Sci. 61:219-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dorman, S. E., V. J. Gill, J. I. Gallin, and S. M. Holland. 1998. Burkholderia pseudomallei infection in a Puerto Rican patient with chronic granulomatous disease: case report and review of occurrences in the Americas. Clin. Infect. Dis. 26:889-894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischer, R., A. Berry, C. G. Gaines, and R. A. Jensen. 1986. Comparative action of glyphosate as a trigger of energy drain in eubacteria. J. Bacteriol. 168:1147-1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frischknecht, F. 2003. The history of biological warfare. Eur. Mol. Biol. Org. 4:S47-S52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerhardt, P., and J. B. Wilson. 1948. The nutrition of brucellae: growth in simple chemically defined media. J. Bacteriol. 56:17-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamad, M. A., S. L. Zajdowicz, R. K. Holmes, and M. I. Voskuil. 2009. An allelic exchange system for compliant genetic manipulation of the select agents Burkholderia pseudomallei and Burkholderia mallei. Gene 430:123-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hatten, L.-A., H. P. Schweizer, N. Averill, L. Wang, and A. B. Schryvers. 1993. Cloning and characterization of the Neisseria meningitidis asd gene. Gene 129:123-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herrero, M., V. De Lorenzo, and K. N. Timmis. 1990. Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 172:6557-6567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoang, T., S. Williams, H. P. Schweizer, and J. S. Lam. 1997. Molecular genetic analysis of the region containing the essential Pseudomonas aeruginosa asd gene encoding aspartate-β-semialdehyde dehydrogenase. Microbiology 143:899-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holden, M. T. G., R. W. Titball, S. J. Peacock, A. M. Cerdeño-Tárraga, T. Atkins, L. C. Crossman, T. Pitt, C. Churcher, K. Mungall, S. D. Bentley, M. Sebaihia, N. R. Thomson, N. Bason, I. R. Beacham, K. Brooks, K. A. Brown, N. F. Brown, G. L. Challis, I. Cherevach, T. Chillingworth, A. Cronin, B. Crossett, P. Davis, D. DeShazer, T. Feltwell, A. Fraser, Z. Hance, H. Hauser, S. Holroyd, K. Jagels, K. E. Keith, M. Maddison, S. Moule, C. Price, M. A. Quail, E. Rabbinowitsch, K. Rutherford, M. Sanders, M. Simmonds, S. Songsivilai, K. Stevens, S. Tumapa, M. Vesaratchavest, S. Whitehead, C. Yeats, B. G. Barrell, P. C. F. Oyston, and J. Parkhill. 2004. Genomic plasticity of the causative agent of melioidosis, Burkholderia pseudomallei. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:14240-14245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.How, H. S., K. H. Ng, H. P. Tee, and A. Shah. 2005. Pediatric melioidosis in Pahang, Malaysia. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 38:314-319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Issack, M. I., C. D. Bundhun, and H. Gokhool. 2005. Melioidosis in Mauritius. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11:139-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacob, G. S., J. R. Garbow, L. E. Hallas, N. M. Kimack, G. M. Kinshore, and J. Schaefer. 1988. Metabolism of glyphosate in Pseudomonas sp. strain LBr. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54:2953-2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jäderlund, L., M. Hellman, I. Sundh, M. J. Bailey, and J. K. Jansson. 2008. Use of a novel nonantibiotic triple marker gene cassette to monitor high survival of Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25 on winter wheat in the field. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 63:156-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jesudason, M. V., A. Anbarasu, and T. J. John. 2003. Septicaemic melioidosis in a tertiary care hospital in south India. Indian J. Med. Res. 117:119-121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kang, Y., M. H. Norris, A. R. Barrett, B. A. Wilcox, and T. T. Hoang. 2009. Engineering of tellurite-resistant genetic tools for single-copy chromosomal analysis of Burkholderia spp. and characterization of the Burkholderia thailandensis betBA operon. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:4015-4027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kovach, M. E., P. H. Elzer, D. S. Hill, G. T. Robertson, M. A. Farris, R. M. Roop II, and K. M. Peterson. 1995. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu, C.-M., P. A. McLean, C. C. Sookdeo, and F. C. Cannon. 1991. Degradation of the herbicide glyphosate by members of the family Rhizobiaceae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:1799-1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marinus, M. G., and N. R. Morris. 1974. Biological function for 6-methyladenine residues in the DNA of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Mol. Biol. 85:309-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore, R. A., D. DeShazer, S. Reckseidler, A. Weissman, and D. E. Woods. 1999. Efflux-mediated aminoglycoside and macrolide resistance in Burkholderia pseudomallei. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:465-470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nierman, W. C., D. DeShazer, H. S. Kim, H. Tettelin, K. E. Nelson, T. Feldblyum, R. L. Ulrich, C. M. Ronning, L. M. Brinkac, S. C. Daugherty, T. D. Davidsen, R. T. Deboy, G. Dimitrov, R. J. Dodson, A. S. Durkin, M. L. Gwinn, D. H. Haft, H. Khouri, J. F. Kolonay, R. Madupu, Y. Mohammoud, W. C. Nelson, D. Radune, C. M. Romero, S. Sarria, J. Selengut, C. Shamblin, S. A. Sullivan, O. White, Y. Yu, N. Zafar, L. Zhou, and C. M. Fraser. 2004. Structural flexibility in the Burkholderia mallei genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:14246-14251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Orellana, C. 2004. Melioidosis strikes Singapore. Lancet Infect. Dis. 4:655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Padgette, S. R., D. B. Re, G. F. Barry, D. E. Eichholtz, X. Delannay, R. L. Fuchs, G. M. Kinshore, and R. T. Fraley. 1996. New weed control opportunities: development of soybeans with a Roundup Ready gene, p. 53-84. In S. O. Duke (ed.), Herbicide-resistant crops. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- 37.Pavelka, M. S., Jr. 2007. Another brick in the wall. Trends Microbiol. 15:147-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peñaloza-Vazquez, A., G. L. Mena, L. Herrera-Estrella, and A. M. Bailey. 1995. Cloning and sequencing of the genes involved in glyphosate utilization by Pseudomonas pseudomallei. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:538-543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Phetsouvanh, R., S. Phongmany, P. Newton, M. Mayxay, A. Ramsay, V. Wuthiekanun, and N. J. White. 2001. Melioidosis and Pandora's box in the Lao People's Democratic Republic. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32:653-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poole, K. 2008. Bacterial multidrug efflux-pumps serve other functions. Microbe 3:179-185. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rholl, D. A., L. A. Trunck, and H. P. Schweizer. 2008. In vivo Himar1 transposon mutagenesis of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:7529-7535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rolim, D. B. 2005. Melioidosis, northeastern Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11:1458-1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rotz, L. D., A. S. Khan, S. R. Lillibridge, S. M. Ostroff, and J. M. Hughes. 2002. Public health assessment of potential biological terrorism agents. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:225-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanchez-Romero, J. M., R. Diaz-Orejas, and V. De Lorenzo. 1998. Resistance to tellurite as a selection marker for genetic manipulations of Pseudomonas strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4040-4046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schweizer, H. P., and S. J. Peacock. 2008. Antimicrobial drug-selection markers for Burkholderia pseudomallei and B. mallei. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:1689-1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thongdee, M., L. A. Gallagher, M. Schell, T. Dharakul, S. Songsivilai, and C. Manoil. 2008. Targeted mutagenesis of Burkholderia pseudomallei and Burkholderia thailandensis through natural transformation of PCR fragments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:2985-2989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vandamme, P., J. Govan, and J. LiPuma. 2007. Diversity and role of Burkholderia spp., p. 1-28. In T. Coenye and P. Vandamme (ed.), Burkholderia: molecular microbiology and genomics. Horizon Scientific, Wymondham, United Kingdom.

- 48.Vasil, I. K. 1996. Phosphinithricin-resistant crops, p. 85-91. In S. O. Duke (ed.), Herbicide-resistant crops. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- 49.Wehrmann, A., A. V. Vliet, C. Opsomer, J. Botterman, and A. Schulz. 1996. The similarities of bar and pat gene products make them equally applicable for plant engineering. Nat. Biotechnol. 14:1274-1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Whitlock, G. C., D. M. Estes, and A. G. Torres. 2007. Glanders: off to the races with Burkholderia mallei. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 277:115-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wiersinga, W. J., T. van der Poll, N. J. White, N. P. Day, and S. J. Peacock. 2006. Melioidosis: insight into the pathogenicity of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4:272-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51a.Wilson, D. E., and L. C. Chosewood. 2007. Biosafety in microbiological and biomedical laboratories, 5th ed. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA.

- 52.Wuthiekanun, V., N. Pheaktra, H. Putchhat, L. Sin, B. Sen, V. Kumar, S. Langla, S. J. Peacock, and N. P. Day. 2008. Burkholderia pseudomallei antibodies in children, Cambodia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:301-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu, M., and J. S. H. Tsang. 2006. Use of ribosomal promoters from Burkholderia cenocepacia and Burkholderia cepacia for improved expression of transporter protein in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr. Purif. 49:219-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zablotowicz, R. M., and K. N. Reddy. 2004. Impact of glyphosate on the Bradyrhizobium japonicum symbiosis with glyphosate-resistant transgenic soybean: a minireview. J. Environ. Qual. 33:825-831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]