Abstract

To examine whether the heat-labile enterotoxin gene in porcine enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) strains is as divergent as in human ETEC strains, we sequenced the heat-labile and heat-stable toxin genes from 52 and 33 porcine ETEC strains, respectively. We found that the STa gene is identical, that the LT gene has only two mutations in 4 (of 52) strains, and that both mutations cause a reduction in GM1 binding and toxicity.

Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) strains that colonize small intestines and produce enterotoxins are the major cause of diarrheal disease in humans and animals (8, 16, 18, 21). The key virulence factors of ETEC in diarrhea include enterotoxins and colonization factors or adhesins. Colonization factors or adhesins mediate the attachment of bacteria to host epithelium cells and facilitate bacterial colonization. Enterotoxins disrupt fluid homeostasis and stimulate fluid hyper-secretion in the intestinal epithelial cells that results in diarrhea. Heat-labile toxin (LT) and heat-stable toxin (ST) are the main enterotoxins associated with diarrhea in humans and farm animals, but different LT and ST are produced by human and animal ETEC strains (9, 16).

The LT produced by porcine ETEC strains (pLT) or human ETEC strains (hLT) is a holotoxin-structured protein that has one LTA subunit and five LTB subunits. Although pLT and hLT are highly homologous in structure and function, these two proteins differ antigenetically (9). Sequence comparative studies showed that the following seven amino acids are different between pLT and hLT: the 4th, 213th, and 237th amino acids of the A subunits and the 4th, 13th, 46th, and 102nd amino acids of the B subunits (6, 7). Similarly, STa (ST type 1) carried by human and porcine ETEC strains is also different. The STa associated with porcine diarrhea (pSTa) is a peptide of 18 amino acids, whereas the STa produced by human ETEC strains (hSTa) is 19 amino acids in length (5, 19). Despite the fact that ETEC constructs expressing pLT or hLT, and pSTa or hSTa, are equivalently virulent in causing diarrhea in gnotobiotic pigs (25), pLT and pSTa are typically expressed by porcine ETEC strains that only cause diarrhea in pigs, whereas hLT and hSTa are exclusively produced by human ETEC strains associated with diarrhea in humans. Although pLT and STb, another porcine-specific ST, were occasionally detected in ETEC strains isolated from human diarrheal patients (3), only infections with hSTa+, hLT+, or hSTa+/hLT+ ETEC strains cause diarrhea in humans (17).

Interspecies LT have been intensively compared for molecular and immunological characteristics (4, 10, 20, 23). In contrast, intraspecies LT has not been studied much. For a long time, both pLT and hLT were assumed to be highly conserved. However, a very recent study showed that the hLT gene carried by human ETEC strains is considerably divergent (12). After restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis and DNA sequencing of 51 human ETEC strains, Lasaro et al. reported that the human LT gene had seven polymorphic restriction fragment length polymorphism types and 30 nucleotide polymorphic sites and recognized 16 different hLT types (12). To examine whether the LT gene carried by porcine ETEC strains has a similar heterogeneity, we PCR amplified and DNA sequenced the LT genes and also the STa genes of various ETEC strains isolated from diarrheal pigs and analyzed gene sequence conformity.

Fifty-two porcine ETEC strains that express LT alone or LT together with other toxins (LT+/STb+, LT+/STb+/STa+, LT+/STb+/EAST1+, and LT+/STa+/STb+/EAST1+) and K88ac or F18 fimbria were selected for the sequencing of the LT gene. Those porcine ETEC strains were isolated from pigs with postweaning diarrhea at different farms in South Dakota, Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska, and North Dakota. The eltAB gene encoding LT from these 52 strains was PCR amplified with primers pLT-F (5′-ATCCTCGCTAGCATGTTTTAT-3′) and pLT-R (5′-CCCCTCCGGCCGAGCTTAGTT-3′) (25). PCRs were performed in an MJ PT-100 thermocycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) in a reaction of 50 μl containing 1× Taq DNA polymerase buffer (with Mg2+), 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 0.5 μM each forward and reverse primers, 100 ng of total genomic DNA, and 1 unit Taq DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The PCR program contained one cycle of 2 min at 94°C; 30 cycles of 35 s at 94°C, 35 s at 52°C, and 2 min at 72°C; and an extension of 6 min at 72°C. The amplified PCR products were separated on 1% agarose gels (FMC Bioproducts, Rockland, MA) by electrophoresis and purified using a QIAquick gel extraction kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). A mixture of purified PCR product (100 to 150 ng) and 10 pmol primer was sent to the Nevada Genomic Center at the University of Nevada for sequencing. Three primers, pLT-F, LT192-F (5′-GATTCATCAAGAACAATCCACAGGTG-3′), and LT192-R (5′-CCTGTGATTGTTCTTGATGAATC-3′), were used for sequencing the entire eltAB gene.

The sequences of the eltAB gene from all 52 porcine ETEC strains were aligned and visually examined. We found that the eltAB gene was nearly identical among the sequenced porcine ETEC strains. Forty-eight (of 52) ETEC strains had identical gene sequences, and only four strains showed heterogeneity. The pathotypes of these four strains were K88/LT/STb, K88/LT/STb/STa, K88/LT/STb/EAST1, and F18/LT/STa/STb/Stx2e. Furthermore, only nucleotides coding two amino acids, the 44th (S44N) and the 60th (S60T) of the eltB gene encoding the B subunit, differed among these four strains. To our surprise, neither of these two substitutions were homologous to the hLT gene nor to any of the hLT types recognized by Lasaro et al. (12). Lasaro et al. showed that 11 of the 15 different hLT types shared some homology with pLT, and some hLT types had as many as four amino acids (K4R and K213E of LTA and S4T, R13H, or A46E of LTB; out of seven heterogeneous amino acids) homologous to pLT. Indeed, the hLT6 type differed from the LT of human ETEC prototype H10407 in four amino acids (K4R and K213E of LTA and S4T and A46E of LTB) (12), but all four of these heterogeneous amino acids were homologous to pLT. Similarly, four of the five amino acids that differed from the prototype hLT in the hLT4 type were identical to pLT. That means that the hLT4 and hLT6 types had only three amino acids heterogeneous to pLT but four different residues compared to the hLT prototype. It seems that hLT4 and hLT6 are more likely pLT rather than hLT. Given that the divergence of the pLT and hLT genes is assumed to be a very recent evolutionary event that occurred 0.9 million years ago (23), it is likely that the hLT gene retains some pLT gene characters (amino acids) that could be of their common ancestor. However, a high homology in the pLT gene certainly seems unparallel to the evolution of the hLT gene. Our further sequence comparison indicated that S44N-substituted pLTB [pLTB(S44N)] is homologous to cholera toxin (CT). It has been suggested that the CT and LT genes were derived from the same ancestor but diverged to two lineages about 130 million years ago (23). Then, it is more likely that this pLTB(S44N) represents a plesiomorphic character, meaning a primitive character that belongs to the common ancestor of CT and LT. The retention of this primitive pLTB(S44N) by some porcine ETEC strains suggests that the pLT gene could have evolved at a relatively lower rate. Whether such a lower substitution rate of the LT gene in porcine ETEC strains is associated with a lower host exchange rate or a limited travel range in pigs is unclear to us. However, future studies to determine whether an increase in sampling sizes, by including porcine ETEC strains from a greater geographic coverage, could reveal a higher heterogeneity or a greater evolution rate in the pLT gene will be worthwhile.

To examine whether the heterogeneity of pS44N and pS60T at the B subunit could affect the biological function of pLT, we cloned the native pLT gene into vector pBR322 (p8458), performed site-directed mutation of the eltAB gene for a substitution of S44N or S60T, and tested these two mutated LT proteins for their binding capability to GM1 receptors and their enterotoxic activity in stimulating intracellular cyclic AMP (cAMP) in cells. Primers pBRNheI-F2 (5′-CAGCATCGCCATTCACTATG-3′) and pBREagI-R (5′-AGATGACGACCATCAGGGAC-3′) were designed to amplify the porcine eltAB gene. The amplified eltAB gene products and vector pBR322 were digested with NheI and EagI (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA), separated by gel electrophoresis, purified with the QIAquick gel extraction kit, and then ligated with T4 DNA ligase (Promega, Madison, WI). Two microliters of the T4-ligated products were introduced into 25 μl of TOPO cells (Invitrogen, Valencia, CA) in a standard electroporation. Antibiotic-selected colonies were initially screened by PCR, and positive colonies were sequenced to ensure that the cloned gene was in the reading frame. The verified clone was selected as a pLT recombinant strain and designated strain 8458. To construct mutant strains, two pairs of primers, LTB44-F (5′-ATCATTACATTTAAGAACGGCGAA-3′) and LTB44-R (5′-TTCGCCGTTCTTAAATGTAATGAT-3′) and LTB60-F (5′-CAACATATAGACACCCAGAAAAAAGCC-3′) and LTB60-R (5′-GGCTTTTTTCTGGGTGTCTATATGTTG-3′), were used for site-directed mutation at nucleotides coding the 44th and 60th amino acids of the LTB subunit, respectively. Briefly, the amplified products from two separate PCRs, one using pBRNheI-F2 with LTB44-R or LTB60-R and the other using pBREagI-R with LTB44-F or LTB60-F, with recombinant pLT plasmid p8458 as the DNA template, were overlapped in a third splicing overlap extension PCR to produce mutated pLT genes. The splicing overlap extension PCR products were digested with NheI and EagI restriction enzymes and ligated into vector pBR322 for the p8647 (S44N) and p8649 (S60T) plasmids. Plasmids p8647 and p8649 were separately introduced into TOPO 10 E. coli cells (Invitrogen) for mutant strains 8647 (S44N) and 8649 (S60T).

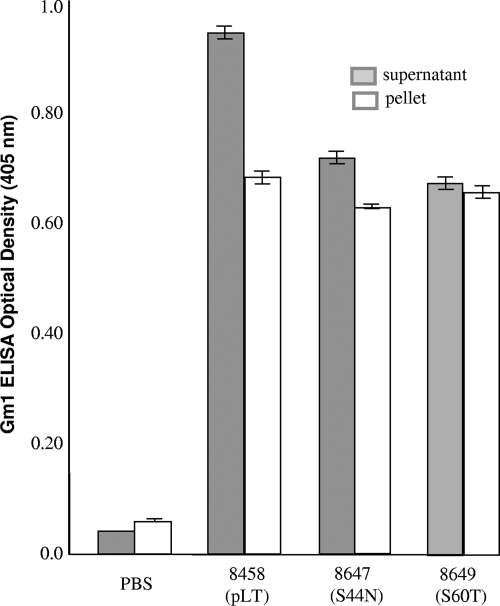

Equivalent amounts of cells from overnight-grown cultures of the recombinant (8458) and two mutant (8647 and 8649) strains were used for total protein preparation by using bacterial protein extraction reagent (B-PER in phosphate buffer; Pierce, Rockford, IL). Both pelleted protein samples (periplasmic proteins) and culture supernatant samples (outer-membrane secreted proteins) were used in a GM1 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to examine whether a substitution at the 44th or 60th amino acid would affect the binding of LT to GM1 receptors. Anti-CT rabbit antiserum (1:5,000; Sigma) and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (1:5,000; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) were used as the primary and secondary antibodies as described previously (2, 14, 24). GM1 ELISA data indicated optical density (OD) values from the pellet samples of strains 8548, 8647, and 8649 and phosphate-buffered saline of 0.677 ± 0.004, 0.616 ± 0.001, 0.647 ± 0.004, and 0.006 ± 0, whereas the OD values of the supernatant samples which were vacuum concentrated were 0.949 ± 0.008, 0.726 ± 0.004, 0.660 ± 0.005, and 0.05 ± 0.002, respectively (Fig. 1). Statistical analysis using the Student t test with two-tailed distribution indicated that the binding of the pellet samples from the native and the mutated LT to GM1 was not significantly different (P = 0.10 and P = 0.45, respectively). However, the GM1 binding from the supernatant samples of the LT mutant strains was significantly lower than that of the LT recombinant strain (P < 0.01 and P < 0.01, respectively).

FIG. 1.

GM1 ELISA to detect LT proteins expressed by the pLT recombinant (8458) and mutant [8647(S44N) and 8649(S60T)] strains. Protein samples from the pellet and vacuum-concentrated supernatants of overnight-grown cultures were used in the GM1 ELISA. Each sample was assayed in triplicate to calculate OD means and standard deviations. Anti-CT serum (1:5,000) was used as the primary antibody and goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated immunoglobulin G (1:5,000) was used as the secondary antibody. OD values were measured after a 20-min reaction with peroxidase substrates (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD) at a wavelength of 405 nm.

Our GM1 ELISA data indicated that the supernatant sample of the recombinant strain expressing a native LT had a greater GM1 binding activity. This could suggest that the recombinant strain had more LT protein crossing the outer membrane and being secreted in the supernatant than either mutant strain or that mutations at the B subunit negatively affected the binding of LT proteins to GM1 receptors. It has been reported that a single amino acid mutation of the LTB or CTB subunit resulted in lower GM1 binding activity, especially mutations of residues from the binding pocket (13, 15, 22). When amino acid 33 or 88 of the CTB subunit was replaced, both mutants failed to bind or bound poorly to GM1 (22), and when a substitution at residue 57 of its B subunit occurred, this CT mutant showed 1.5-log-lower GM1 binding than the native CT (1, 13). Similarly, when amino acid 46 or 47 of the B subunit was replaced, both LT mutants exhibited lower GM1 binding activity than the wild-type LT strain (13). However, in contrast to our observation that our 8647 and 8649 mutant strains showed lower GM1 binding activity in the supernatant, Mudrak et al. indicated that the T47A mutant strain had more LT protein detected in the supernatant than the wild-type strain (13). Whether and how a mutation at amino acid 44 or 60 of the B subunit affects the formation, stability, or secretion of the mutant LT proteins will be studied in the future.

To examine whether the lower GM1 binding activity of the supernatant samples from the mutant strains was caused by a lower LT production, we conducted an ELISA by directly coating an ELISA plate with total proteins from the pellet and supernatant samples of each strain (without GM1) and by using anti-CT antiserum to quantify the LT protein. ELISA data showed that the OD values of strains 8458, 8647, and 8649 were 0.209 ± 0.005, 0.225 ± 0.009, and 0.21 ± 0 in the supernatant samples and 0.571 ± 0.025, 0.614 ± 0.060, and 0.616 ± 0.026 in the pellet samples, respectively. A Student t test indicated that there were no significant differences between the recombinant strain and the mutant strains in the OD values for the pellet and supernatant protein samples (P = 0.26 and P = 0.84, respectively, for the supernatant samples; P = 0.34 and P = 0.10, respectively, for the pellet samples). These data suggested that a similar amount of LT proteins was produced among these three strains.

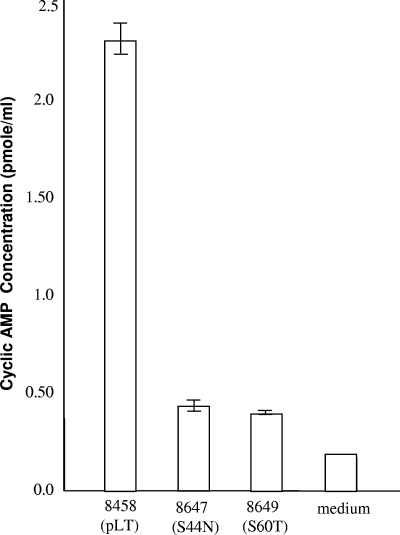

A single amino acid substitution of the B subunit can result in a reduction in not only GM1 binding but also toxicity for the mutated LT proteins (11, 13, 22). To study whether the mutation of S44N or S60T at the B subunit affected pLT toxicity, we measured the recombinant and mutant strains for their stimulation of intracellular cAMP levels in T-84 cells by using a cAMP competitive enzyme immunoassay (EIA) kit (Invitrogen) by following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 1 × 105 T-84 cells were seeded in each well of a 24-well plate. After removing the Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM/F12; Gibco/Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY), 75 μl of overnight-grown (in 4AA medium) supernatant of the recombinant or each mutant strain (in triplicate) was added to each well. The cells were lysed with 100 μl of 0.1 M HCl after 2 h of incubation and then neutralized. A total of 100 μl of lysis supernatant was mixed with kit-supplied conjugates and antibody reagents, and the mixture was added to each well of the supplied EIA plate. After incubation on a shaker at 500 rpm at room temperature for 2 h, the plate was washed and dried by blotting, and p-nitrophenyl phosphate substrate solution was added. The OD was measured at 405 nm after 20 min of development. Data from the cAMP ELISA indicated that cAMP levels in T-84 cells incubated with supernatant samples from strains 8458, 8647, and 8649 (from equivalent amounts of cells) were 2.3 ± 0.1, 0.46 ± 0.05, and 0.35 ± 0.01 pmol/ml, respectively (Fig. 2). Data clearly indicated that the mutations of S44N and S60T reduced the LT toxic activity. Knowing that it is the A subunit that determines the toxicity of LT and CT, whereas the LTB and CTB subunits mediate the binding of the toxin to the host GM1 receptors, we thought that substitution at the B subunits would not affect toxicity. However, we believe that mutations at the B subunits could alter LT protein structure and reduce the binding of the holotoxin to the host GM1 receptors, thus resulting in the reduction of toxic activity.

FIG. 2.

Intracellular cAMP ELISA to detect the toxicity of native LT and mutated LT proteins. Supernatants (in 4AA medium) of overnight-grown cultures from the 8458 (recombinant), 8647 (S44N), and 8649 (S60T) strains were used to stimulate an increase in intracellular cAMP levels in T-84 cells by using a cyclic GMP EIA kit (Invitrogen).

The estA gene encoding STa from 33 STa-positive porcine ETEC strains was also sequenced for conformity. This porcine estA gene was PCR amplified using primers pSTaSfcI-F2 and STaEagI-R under conditions described previously (25). The PCR products were purified and sequenced with pSTaSfcI-F2 primer. The sequencing data showed that all sampled STa genes were identical and of porcine origin.

Sequence data from our study clearly indicated that both LT and STa expressed by porcine ETEC strains are porcine specific. The LT gene of porcine ETEC strains showed little heterogeneity, and the STa gene is identical. Information from this study will be helpful for a prevalence study of toxin genes among porcine ETEC strains and toxin gene evolution and possibly instructive in antitoxin vaccine development. However, future studies with increasing sampling sizes and a greater geographic coverage will be helpful to understand divergence in the LT and STa genes among porcine ETEC strains.

Acknowledgments

We thank two anonymous reviewers and E. Nelson for their valuable comments.

Financial support for this study was provided by NIH grant AI068766 (W.Z.), National Pork Board grant NPB-07-006 (W.Z.), and the South Dakota Agricultural Experiment Station.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 14 August 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aman, A. T., S. Fraser, E. A. Meritt, C. Rodigherio, M. Kenny, M. Ahn, W. G. Hol, N. A. Williams, W. I. Lencer, and T. R. Hirst. 2001. A mutant cholera toxin B subunit that binds GM1 ganglioside but lacks immunomodulatory or toxic activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:8536-8541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berberov, E. M., Y. Zhou, D. H. Francis, M. A. Scott, S. D. Kachman, and R. A. Moxley. 2004. Relative importance of heat-labile enterotoxin in the causation of severe diarrheal disease in the gnotobiotic piglet model by a strain of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli that produces multiple enterotoxins. Infect. Immun. 72:3914-3924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chapman, T. A., X. Y. Wu, I. Barchia, K. A. Bettelheim, S. Driesen, D. Trott, M. Wilson, and J. J.-C. Chin. 2006. Comparison of virulence gene profiles of Escherichia coli strains isolated from healthy and diarrheic swine. Infect. Immun. 72:4782-4795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dallas, W. S. 1983. Conformity between heat-labile toxin genes from human and porcine enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 40:647-652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dreyfus, L. A., J. C. Frantz, and D. C. Robertson. 1983. Chemical properties of heat-stable enterotoxins produced by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli of different host origins. Infect. Immun. 42:539-548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finkelstein, R. A. 1988. Cholera, the cholera enterotoxins, and the cholera enterotoxin-related enterotoxin family, p. 85-102. In P. Owen and T. J. Foster (ed.), Immunochemical and molecular genetic analysis of bacterial pathogens. Elsevier, New York, NY.

- 7.Finkelstein, R. A., M. F. Burks, A. Zupan, W. S. Dallas, C. O. Jacob, and D. S. Ludwig. 1987. Epitopes of the cholera family of enterotoxins. Rev. Infect. Dis. 9:544-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilligan, P. H. 1999. Escherichia coli. EAEC, EHEC, EIEC, ETEC. Clin. Lab. Med. 19:505-521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hol, W. G. J., T. K. Sixma, and E. A. Merritt. 1995. Structure and function of E. coli heat-labile enterotoxin and cholera toxin B pentamer, p. 195-223. In J. Moss, B. Iglewski, M. Vaughau, and A. T. Tu (ed.), Bacterial toxins and virulence factors in disease. Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York, NY.

- 10.Honda, T., T. Tsuji, Y. Takeda, and T. Miwatani. 1981. Immunological nonidentity of heat-labile enterotoxins from human and porcine enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 34:337-340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iida, T., T. Tsuji, T. Honda, T. Miwatani, S. Wakabayashi, K. Wada, and H. Matsubara. 1989. A single amino acid substitution in B subunit of Escherichia coli enterotoxins affects its oligomer formation. J. Biol. Chem. 264:14065-14070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lasaro, M. A., J. F. Rodrigues, C. Mathias-Santos, B. E. C. Guth, A. Balan, M. E. Sbrogio-Almeida, and L. C. S. Ferreira. 2008. Genetic diversity of heat-labile toxin expressed by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli strains isolated from humans. J. Bacteriol. 190:2400-2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mudrak, B., D. L. Rodriguez, and M. J. Kuehn. 2009. Residues of heat-labile enterotoxins involved in bacterial cell surface binding. J. Bacteriol. 191:2917-2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ristaino, P. A., M. M. Levine, and C. R. Young. 1983. Improved GM1-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin. J. Clin. Microbiol. 18:808-815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodighiero, C., Y. Fujinaga, T. R. Hirst, and W. I. Lencer. 2001. A cholera toxin B-subunit variant that binds ganglioside GM1 but fails to induce toxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 276:36939-36945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sears, C. L., and J. B. Kaper. 1996. Enteric bacterial toxins: mechanisms of action and linkage to intestinal secretion. Microbiol. Rev. 60:167-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steinland, H., P. Valentiner-Branth, M. Perch, F. Dias, T. K. Fischer, P. Aaby, K. Molbak, and H. Sommerfelt. 2002. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli infections and diarrhea in a cohort of young children in Guinea-Bissau. J. Infect. Dis. 186:1740-1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Svennerholm, A. M., and D. Steels. 2004. Progress in enteric vaccine development. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 18:421-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson, M. R., and R. A. Giannella. 1985. Revised amino acid sequence for heat-stable enterotoxin produced by an Escherichia coli strain (18D) that is pathogenic for humans. Infect. Immun. 47:834-836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsuji, T., S. Taga, T. Honda, Y. Takeda, and T. Miwatani. 1982. Molecular heterogeneity of heat-labile enterotoxins from human and porcine enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 38:444-448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walker, R. I. 2005. Considerations for development of whole cell bacterial vaccines to prevent diarrheal diseases in children in developing countries. Vaccine 23:3369-3385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolf, A. A., M. G. Jobling, D. E. Saslowsky, E. Kern, K. R. Drake, A. K. Kenworthy, R. K. Holmes, and W. I. Lencer. 2008. Attenuated endocytosis and toxicity of a mutant cholera toxin with decreased ability to cluster ganglioside GM1 molecules. Infect. Immun. 76:1476-1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamamoto, T., T. Tamura, and T. Yokota. 1987. Evolutionary origin of pathogenic determinants in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli and Vibrio cholerae O1. J. Bacteriol. 169:1352-1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang, W., E. M. Berberov, J. Freeling, D. He, R. A. Moxley, and D. H. Francis. 2006. Significance of heat-stable and heat-labile enterotoxins in porcine colibacillosis in an additive model for pathogenicity studies. Infect. Immun. 74:3107-3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang, W., D. C. Robertson, C. Zhang, W. Bai, M. Zhao, and D. H. Francis. 2008. Escherichia coli constructs expressing human or porcine enterotoxins induce identical diarrheal diseases in a piglet infection model. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:5832-5837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]