Abstract

Substance P (SP) is known to be a peptide that facilitates epileptic activity of principal cells in the hippocampus. Paradoxically, in other models, it was found to be protective against seizures by activating substance P receptor (SPR)-expressing interneurons. Thus, these cells appear to play an important role in the generation and regulation of epileptic seizures. The number, distribution, morphological features and input characteristics of SPR-immunoreactive cells were analysed in surgically removed hippocampi of 28 temporal lobe epileptic patients and 8 control hippocampi in order to examine their changes in epileptic tissues. SPR is expressed in a subset of inhibitory cells in the control human hippocampus, they are multipolar interneurons with smooth dendrites, present in all hippocampal subfields. This cell population is considerably different from SPR-positive cells of the rat hippocampus. The CA1 region was chosen for the detailed morphological analysis of the SPR-immunoreactive cells because of its extreme vulnerability in epilepsy. The presence of various neurochemical markers identifies functionally distinct interneuron types, such as those responsible for perisomatic, dendritic or interneuron-selective inhibition. We found considerable colocalization of SPR with calbindin but not with parvalbumin, calretinin, cholecystokinin and somatostatin, therefore we suppose that SPR-positive cells participate mainly in dendritic inhibition. In the non-sclerotic CA1 region they are mainly preserved, whereas their number is decreased in the sclerotic cases. In the epileptic samples their morphology is considerably altered, they possessed more dendritic branches, which often became beaded. Analyses of synaptic coverage revealed that the ratio of symmetric synaptic input of SPR-immunoreactive cells have increased in epileptic samples. Our results suggest that SPR-positive cells are preserved while principal cells are present in the CA1 region, but show reactive changes in epilepsy including intense branching and growth of their dendritic arborisation.

Keywords: GABA, SPR, Temporal lobe epilepsy, synaptic reorganization, plasticity, inhibition

Introduction

Substance P (SP) may play a crucial role in the generation and maintenance of epileptic seizures. Treatment with SP enhances the self sustaining status epilepticus induced by perforant path stimulation or kainate (Zachrisson et al., 1998, Liu et al., 1999a, Liu et al., 1999b). On the other hand, SP receptor activation may be protective against epilepsy. Activation of SP receptors (SPR) in the rat entorhinal cortex was found to decrease acute epileptiform activity by increasing local GABA release (Maubach et al., 1998, Stacey et al., 2002). In the rat hippocampus, the direct action of SP on SPR-immunoreactive interneurons can enhance inhibitory synaptic input to pyramidal cells via increasing the excitability of these interneurons (Ogier and Raggenbass, 2003).

The majority of hippocampal SP is of extrahippocampal origin, derived from the SP-positive cells of the supramammillary nucleus (SUM) (Borhegyi and Leranth, 1997a, Borhegyi and Leranth, 1997b). This is likely to be an excitatory input (facilitating the population spikes in the dentate gyrus) (Mizumori et al., 1989, Carre and Harley, 1991) terminating in the inner third of the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus and in the stratum (str.) pyramidale and oriens of the CA2 and CA3a,b regions (Vertes, 1992, Magloczky et al., 1994, Nitsch and Leranth, 1994a). Several studies highlight the potential role of the supramammillo-hippocampal projection in seizure generation as it appears an efficient excitatory input of the hippocampus. In primates these afferents terminate on inhibitory interneurons as well, which influences the information flow at different levels of the excitatory trisynaptic loop (Leranth and Nitsch, 1994).

Substance P receptor is expressed in several areas of the mammalian central nervous system (Kiyama et al., 1993, Shigemoto et al., 1993, Nakaya et al., 1994). Its endogenous ligand, substance P, is a neuromodulator peptide, a member of the tachykinin family encoded by the pre-pro-tachykinin-A (PPT-A) gene (Nawa et al., 1984). There is a considerable mismatch in the site of release and the receptors. The ligand may reach the target receptors mainly by diffusion acting in a non-synaptic fashion (Duggan et al., 1990, Liu et al., 1994, Mantyh et al., 1995).

SPR-immunocytochemistry does not result in any axonal staining, it labels only the soma and dendritic membranes (Acsady et al., 1997, Sloviter et al., 2001). Thus, SP is unlikely to exert any presynaptic effects. SPR-immunoreactive cells of the rat hippocampus are GABAergic interneurons. They are heterogeneous not only in terms of their morphology but also in function and neurochemical marker content (Acsady et al., 1997, Sloviter et al., 2001). On the basis of cell morphology and localization we can assume that the human SPR-immunostained cells are also GABAergic inhibitory interneurons in the hippocampus (Magloczky et al., 2000).

Different populations of interneurons in human hippocampus show various changes in epilepsy. Some of them seem to be resistant, and are present in large numbers even in the epileptic tissue (Babb et al., 1989, Sloviter et al., 1991, Houser et al., 1992, Magloczky et al., 2000, Wittner et al., 2002), while others disappear almost completely (de Lanerolle et al., 1988, Magloczky et al., 2000). The surviving cells show morphological and functional alterations, they establish abnormal neuronal networks in response to epilepsy (Sutula et al., 1989, Mathern et al., 1995, Houser, 1999, Loup et al., 2000, Wittner et al., 2001, Ratzliff et al., 2002, Magloczky and Freund, 2005).

In an earlier study we described that SPR-positive interneurons were present in large numbers in the human epileptic dentate gyrus, although their location and morphology changed considerably. The majority of these interneurons were found in the hilus in the control tissue, whereas they were located in str. moleculare in the epileptic dentate gyrus. It is interesting to note that sprouting of the supramammillo-hippocampal pathway was observed in the epileptic human hippocampus (Magloczky et al., 2000), the fibres occupied the entire str. moleculare, where the SPR-positive interneurons were present. This different location suggests a switch from a primarily feedback to a feed-forward drive of these interneurons by both supramammillary and entorhinal afferents (Magloczky et al., 2000).

In the present study we examined the location, morphology and input characteristics of SPR-immunoreactive interneurons in the CA1 region of human control and epileptic hippocampi derived from patients with therapy resistant temporal lobe epilepsy. The CA1 region is known to be the most vulnerable hippocampal subfield in temporal lobe epilepsy, and we were interested in alterations of an interneuron type in CA1 that was found to show plastic changes in response to epilepsy in the dentate gyrus. The cellular morphological changes were quantified by determining the branching pattern of the cells. Alterations in the synaptic input of SPR-immunoreactive cells were also quantified to see whether the recruitment of SPR-immunoreactive cells has changed in the reorganized network.

Experimental procedures

SPR-containing cells were examined in the hippocampus of 8 control subjects and in temporal lobe samples surgically removed from 28 patients with intractable temporal lobe epilepsy. The study was approved by the ethic committee at the Regional and Institutional Committee of Science and Research Ethics of Scientific Council of Health (TUKEB 5-1/1996) and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. A written informed consent for the study was obtained from every patient before surgery. Standard anterior temporal lobectomies were performed, i.e. the anterior third of the temporal lobe was removed together with the temporomedial structures (Spencer and Spencer, 1985). The patients were operated on in the Department of Neurosurgery, New York University, School of Medicine, New York, USA. Control hippocampi were kindly provided by the Lenhossek Human Brain Program, Semmelweis University, Budapest. These control subjects (n=8) died suddenly from causes not directly involving any brain disease. The control subjects were processed for autopsy in the Department of Forensic Medicine of the Semmelweis University Medical School, Budapest, brains were removed 2–4 hours after death. None of the control subjects had a record of any neurological disorders (Table 1).

Table 1.

Data of the examined control and epileptic subjects.

| Control subjects | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control code number | Gender | Age (Year) | Post mortem delay (hours) | Cause of death | ||

| 3. | F | 37 | 2 | respiratory failure | ||

| 4. | M | 65 | 2 | lung embolism | ||

| 5. | F | 48 | 2 | cardiac arrest | ||

| 6. | M | 71 | 2 | cardiac arrest | ||

| 7. | M | 65 | 2 | cardiac arrest | ||

| 9. | M | 51 | 2 | cardiac arrest | ||

| 10. perfusion -fixed | M | 53 | 2 | suffocation | ||

| 11. perfusion -fixed | M | 56 | 4 | cardiac arrest | ||

| Epileptic subjects | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient’s code number | Gender | Age (years) | Age at onset of epilepsy (years) | Duration of epilepsy (years) | Anamnesis and pathology | Pathological type |

| 3. | F | 22 | 8 month | 21 | meningeoencephalitis | 3. (sclerotic) |

| 4. | M | 31 | 24 | 7 | head injury | 3. (sclerotic) |

| 5. | M | 48 | 16 | 32 | - | 3. (sclerotic) |

| 6. | M | 21 | 18 | 3 | head-injury | 3. (sclerotic) |

| 9. | F | 32 | 1 | 31 | - | 2. (patchy) |

| 15. | M | 42 | No data | - | 3. (sclerotic) | |

| 16. | F | 34 | No data | Kaposi sarcoma | 3. (sclerotic) | |

| 17. | M | 27 | 17 | 10 | - | 1. (mild) |

| 20. | F | 35 | 12 | 23 | - | 3. (sclerotic) |

| 21 | M | 35 | 2 | 33 | neuronal migration desease | 3. (sclerotic) |

| 24. | M | 41 | 3 | 38 | ganglioneurocytoma | 1. (mild) |

| 26 | M | 41 | 1 | 40 | - | 3. (sclerotic) |

| 27. | F | 36 | 3 | 33 | - | 3. (sclerotic) |

| 28. | F | 46 | 22 | 24 | foetalis distress | 1. (mild) |

| 31. | M | 42 | 25 | 17 | head-injury | 1. (mild) |

| 33. | M | 38 | 28 | 10 | cavernosus haemangioma | 2. (patchy) |

| 34. | F | 34 | 5 | 29 | - | 2. (patchy) |

| 43. | F | 44 | 4 | 40 | - | 2. (patchy) |

| 49. | F | 48 | 13 | 35 | neuronal migration desease | 3. (sclerotic) |

| 60. | No data | No data | No data | No data | - | 3. (sclerotic) |

| 63. | F | 38 | 0 | 38 | - | 3. (sclerotic) |

| 67. | M | 45 | 16 | 29 | - | 1. (mild) |

| 70. | F | 66 | 20 | 46 | - | 3. (sclerotic) |

| 77. | M | 37 | 28 | 9 | virus inf. | 3. (sclerotic) |

| 81. | F | 22 | 17 | 5 | head-injury, coma, grey substance heterotopia | 1. (mild) |

| 82. | M | 37 | 14 | 23 | encephalitis | 3. (sclerotic) |

| 84. | F | 42 | 29 | 13 | ganglioneurocytoma | 2. (patchy) |

| 96. | F | 26 | 7 | 19 | born prematurely | 2. (patchy) |

Immunocytochemistry

After removal, the epileptic tissue was immediately cut into 3–4-mm-thick blocks, and immersed into a fixative containing 4% paraformaldehyde, 0.05% glutaraldehyde and 0.2% picric acid in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB, pH 7.4). Fixative was hourly changed to a fresh solution during constant agitation for 6 h, and then the blocks were postfixed in the same fixative solution without glutaraldehyde overnight. In the case of 6 samples (Nos. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9) from the 8 control hippocampi the procedure was similar. Two of the control brains (Nos. 10, 11) were removed from the skull after death (2 h and 4 h, respectively), both internal carotid and vertebral arteries were cannulated, and the brains were perfused first with physiological saline (2 l in 30 min) followed by a fixative solution containing 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.2% picric acid in 0.1 M PB (6 l in 1.5 h). The hippocampus was removed after perfusion and cut into 3–4 mm-thick blocks, and was postfixed in the same fixative solution overnight.

From the blocks 60 μm thick slices were cut on a Vibratome, and sections were processed for immunostaining. Following washing in 0.1 M PB (6×20 min) the sections were immersed in 30% sucrose in 0.1 M PB for 1–2 days, then freeze-thawed three times over liquid nitrogen, and washed in Tris-buffered saline (TBS, pH 7.4, 2×10min). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by 1% H2O2 in the first TBS for 10 min. TBS was used for all the washes (3×10 min between each antiserum) and for dilution of the antisera. Non-specific immunoglobulin binding of the tissue was blocked by 5% milk powder and 2% bovine serum albumin in TBS. It was followed by incubation in the primary antibody for two days at 4 °C. A polyclonal rabbit antiserum against substance P receptor (1:1000, Shigemoto et al., 1993) was used. For the visualization of positive elements biotinylated secondary anti-rabbit serum was applied (2 hours), (3×10 min washing in TBS) followed by avidin-biotinylated horseradish peroxidase complex (1.5 hours). After washing in TBS (2×10 min) and Tris buffer (TB, pH 7.6, 2×10 min) the sections were preincubated for 20 min in DAB chromogene (3,3′-diaminobenzidine-tetrahydrochloride, 0.05M, dissolved in TB pH 7.6) and then developed by 0.01 % H2O2. Sections were then treated with 1% OsO4 in PB for 40 min, dehydrated in ethanol (1% uranyl acetate was added at the 70% ethanol stage for 40 min) and mounted in Durcupan (ACM, Fluka). The control hippocampi were processed in the same way.

After light microscopic examination, areas of interest were reembedded and sectioned for electron microscopy. Ultrathin serial sections were collected on Formvar-coated single slot grids, stained with lead citrate, and examined in a Hitachi 7100 electron microscope.

Fluorescent immunostaining

For immunofluorescent staining the following primary antibodies were used: polyclonal rabbit antiserum against SPR (1:1000, Shigemoto et al., 1993), monoclonal mouse antiserum against calbindin (CB) (1:1000, SWANT, Bellinzona, Switzerland), monoclonal mouse antiserum against parvalbumin (PV) (1:1000, SIGMA-ALDRICH, St. Louis, MO, USA), polyclonal mouse antiserum against calretinin (CR) (1:1000, SWANT, Bellinzona, Switzerland), polyclonal mouse antiserum against cholecystokinin (CCK) (1:1000, JN Walsh, UCLA), monoclonal rat antiserum against somatostatin (SOM) (1:50, CHEMICON International, Temecula, CA, USA). After washing in TBS (3×10 min) CY3-conjugated goat-anti-rabbit (1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA), Alexa-conjugated donkey-anti-mouse (1:100, Molecular Probes, Eugene, USA), Alexa-488-conjugated goat-anti-mouse (1:100, Molecular Probes, Eugene, USA), FITC-conjugated goat-anti-rat (1:50, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) were used as secondary antibodies. After a three-hour incubation in dark and 4×10 min washing in TBS the sections were covered with Vectashield. The double fluorescent sections were examined in a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope with Attoarc fluorescence illuminators using filters for FITC (exciting filter bandpass 450–490), Alexa-488 (exciting filter bandpass 512–542) and Cy3 (exciting filter bandpass 530–560).

Quantitative analysis of cell number and dendritic branchpoints

To obtain data on changes of SPR-immunoreactive cell number, all cells from two to four representative sections were drawn by camera lucida from control samples (numbers 6, 10, 11) and from patients of each pathological group (patient numbers 24, 28, 81, 9, 33, 34, 96 with mild or moderate and numbers 5, 15, 20, 27, 3, 16 with severe sclerosis). The drawings were scaled down and scanned. The area of the CA1 region was measured by the NIH ImageJ program. In each control and epileptic sample the cells were counted and the cell number was determined per unit area (mm2). To examine the alteration of the dendritic arborisation, segments of the CA1 region of each type were drawn by camera lucida (control numbers 6, 10, patient numbers 24, 28 with mild, 9, 33 with patchy and 5, 16, 27 with severe sclerosis) and the total number of dendritic branchpoints of each cell was determined. Data were evaluated by the Statistica 6.0 program. Mann-Whitney U-test and ANOVA was applied.

Quantitative electron microscopic analysis

For the examination of the synaptic coverage of SPR-immunostained cells, the strata oriens, pyramidale and radiatum were reembedded from the CA1 region of each pathological type and sectioned for electron microscopy. The following samples were used: numbers 10, 11 (controls), 24, 67 (mild), 9, 33, 84 (patchy) and 5, 6, 15 (sclerotic). According to the systematic random sampling every tenth section was examined to avoid the repeated occurrence of the same profile. Each immunolabelled dendrite was photographed from single sections (number of examined dendrites: n=257 in control, 168 in mild, 377 in patchy and 205 in sclerotic cases). The perimeter of the dendrites and the length of the synaptic active zones were measured by NIH ImageJ. The synaptic coverage was determined as total synaptic length (μm) per 100 μm dendrite perimeter. Data were evaluated by the Statistica 6.0 program. Mann-Whitney U-test was applied.

Dependence of SPR immunostaining on age, fixation and post-mortem delay

In a preliminary experiment we examined 12 control brains with different post mortem delays and age in both genders. Although the general distribution and morphology of the cells was similar in each case, the long post mortem delay influenced the quality and quantity of immunostaining. The smallest number of cells was found in immersion fixed subjects with post mortem delays longer than 6 hours, therefore these control subjects were excluded from the present study. The electron microscopic analysis of tissues with 2–4 hours post mortem delay revealed acceptable ultrastructural preservation even in the immersion-fixed controls, although it was inferior to the perfused tissue. The preservation of the post mortem perfused controls (10 and 11) was comparable to the immediately fixed epileptic samples and perfusion fixed rat tissues (Acsady et al., 1997). The SPR-staining in the control subjects included in the present study were similar to each other, and differed considerably from the immunolabelled cells of the epileptic cases. Therefore, we concluded that the differences found between control and epileptic tissues in the present study are likely to be associated with epilepsy.

We found that the age of the subject did not affect the quality and quantity of immunostaining if the subjects had no central nervous system disorders diagnosed. Immunostaining for SPR resulted in weaker reaction and lower number of cells in elder subjects showing the signs of arteriosclerosis. Therefore we excluded all subjects older than 80.

Results

The changes in the distribution, morphology and synaptic input characteristics of the SPR-immunoreactive interneurons were examined and compared in the CA1 region of 28 epileptic and 8 control human hippocampi.

All patients examined in the present study had therapy resistant epilepsy of temporal lobe origin. The seizure focus was identified by multimodal studies including video-EEG monitoring and/or PET. The patients had different degrees of hippocampal atrophy and/or sclerosis. Similarly to our previous studies (Wittner et al., 2002, Wittner et al., 2005) and recent results (de Lanerolle et al., 2003), epileptic patients were divided into four groups based on the principal cell loss and interneuronal changes examined at the light microscopic level as follows: Epileptic Type 1 (mild): similar to control, no considerable cell loss in the CA1 region, pyramidal cells are present, layers are visible and intact, their borders are clearly identified. There is a slight loss in certain interneuron types, mostly in the hilus and the str. oriens of the CA1 region. (N=6). Epileptic Type 2 (patchy): Pyramidal cell loss in patches in the CA1 pyramidal cell layer, but these segments of the CA1 region are not atrophic. Interneuron loss is more pronounced. (N=6). Epileptic Type 3 (sclerotic): the CA1 region is shrunken, atrophic, more than 90 % principal cell loss, occasionally scattered pyramidal cells remained in the CA1 region, separation of the layers is impossible. Only the str. lacunosum-moleculare is present in the CA1 region as a distinct layer, the others could not be separated from each other due to the lack of pyramidal cells and shrinkage of the tissue. This remaining part should contain the layers determined in the control as str. oriens, str. pyramidale and str. radiatum. Mossy fibre sprouting and considerable changes in the distribution and morphology of interneurons can be observed in the samples of this group. (N=16). Epileptic Type 4 (gliotic): the whole hippocampus is shrunken, atrophic, not only the CA1 region, the loss of all cell types can be observed, including the resistant neurons (granule cells, calbindin-positive interneurons). In the present study none of the examined epileptic tissues belonged to this type.

The general qualitative description of the morphology and distribution of the SPR-immunopositive cells was based on a careful analysis of all samples included in the study. The number, morphology and distribution of cells were similar in patients that belonged to the same pathological groups, but differed between groups. The control samples were similar to each other, and differed from the epileptic groups.

Changes in the distribution and morphology of SPR-immunoreactive cells

SPR immunocytochemistry reveals a morphologically heterogeneous, non-principal cell population in the hippocampus. In humans, SPR labels a considerably different cell population than in rats (Acsady et al., 1997, Sloviter et al., 2001). The SPR-immunolabelled cells of the human control hippocampus are also interneurons on the basis of their morphology and localization (Magloczky et al., 2000). This cell population can be found in all regions of the hippocampus, and consists of morphologically diverse cells with usually smooth, occasionally with spiny dendrites. In the Ammon’s horn SPR-positive interneurons are located mainly in the CA1 and CA3a,b regions with the largest numbers in the str. pyramidale and radiatum. Fewer cells can be observed in the CA2 and CA3c subfields. Usually their dendritic arbour runs radially, similar to the orientation of the pyramidal cell apical dendrites.

In the CA1 region the majority of the immunolabelled somata are located in the str. pyramidale and in the str. radiatum (Fig. 1). Multipolar cells with 5–6 dendrites are present in the largest numbers, especially in the str. pyramidale (Fig. 2A). Many of them have one thicker and a few thinner primary dendrites. Fusiform cells can be also distinguished with 1 or 2 primary dendrites running towards the str. lacunosum-moleculare (Fig. 2C). Some bitufted cells can also be observed scattered at the border of the str. radiatum and lacunosum-moleculare in the CA1 region. The characteristic cell type of the str. oriens is horizontally oriented, spindle-shaped bipolar cell with two or three primary dendrites, which run horizontally (Figs. 1, 2B). The SPR-immunoreactive cells of the control samples have long and smooth dendrites in the CA1 subfield. The primary branchpoints are located usually near to the soma.

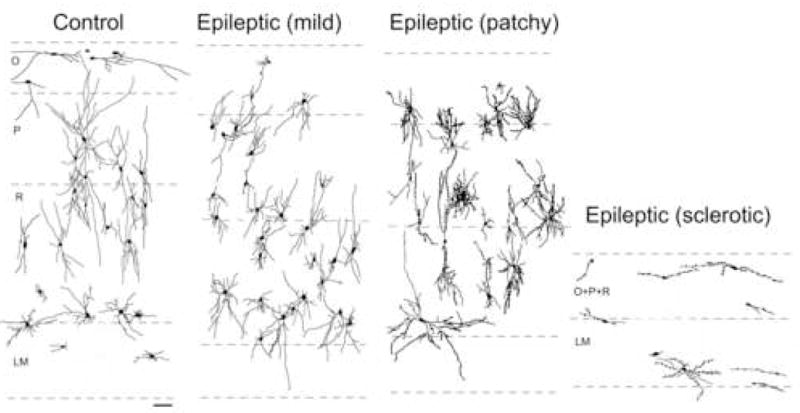

Figure 1.

Camera lucida drawings from the CA1 region show changes in the distribution and morphology of the SPR-immunoreactive interneurons. Note that in the non-sclerotic cases (mild and patchy) the number and distribution of positive cells are similar to the control. However, their morphology is considerably altered, the dendrites have more branches, especially in the patchy type and become beaded. The spindle-shaped cells disappear from the str. oriens. In the sclerotic samples the number of cells is decreased and most of them have only a few distorted dendrites. The dendritic tree of the cells is deformed by the shrinkage of the CA1 region and has a horizontal orientation. Scale: 0.1 mm

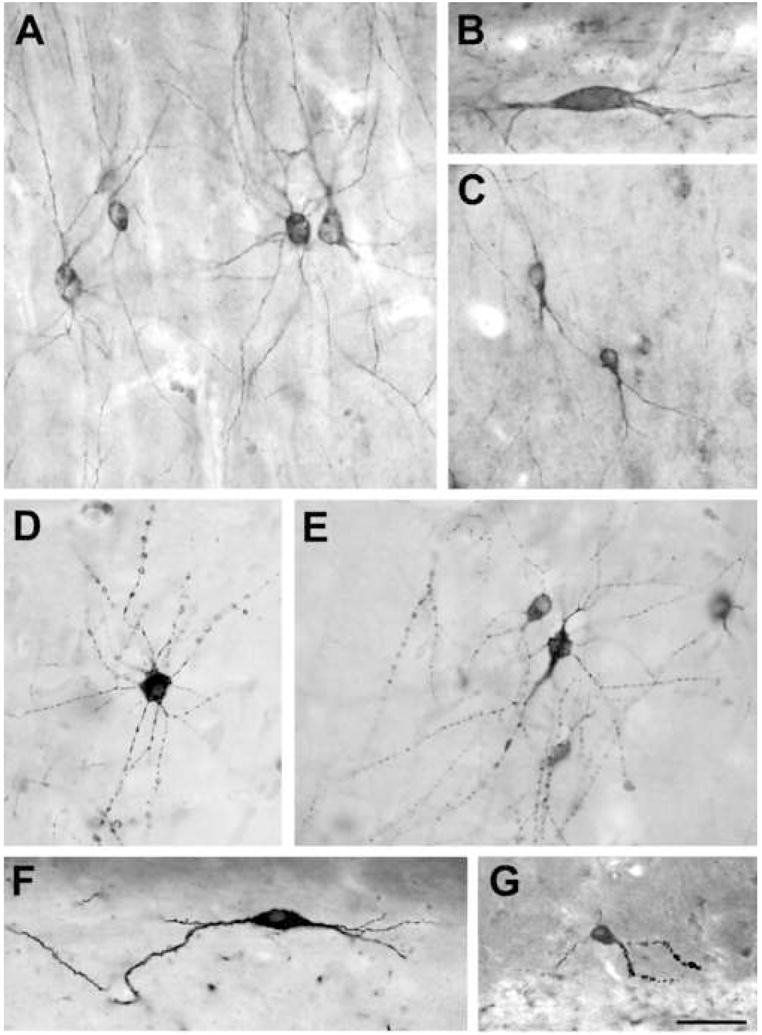

Figure 2.

Morphology of SPR-immunoreactive cells in the human control and epileptic hippocampus. A: The majority of SPR-positive cells in the cornu Ammonis are multipolar cells with several radially oriented, thin primary dendrites. B: In the str. oriens of the CA1 region there are some larger, spindle-shaped horizontal cells. Generally they have two main dendrites of horizontal orientation in this layer. C: The fusiform cells are typical of the str. radiatum. Their single main dendrite branches near the soma and runs towards the str. lacunosum-moleculare. D, E: The morphology of dendrites changes considerably in the non-sclerotic epileptic tissue, they become more numerous, sometimes shorter, often distorted or beaded. F, G: In the sclerotic epileptic samples only few cells survive. Two types can be distinguished: horizontal cells with only a few dendrites (F), and cells with curved, shortened and segmented dendrites (G). In the sclerotic tissue the SPR-immunoreactive dendrites often become spiny. Scale: 50 μm.

The morphology of the SPR-positive cells changed significantly in the epileptic CA1 region. The degree of the changes largely depends on the severity of cell loss and sclerosis of the hippocampus (Fig. 2D–G).

Camera lucida drawings were made of the CA1 subfield with mild, patchy and sclerotic damage to analyze the changes in cell number and distribution in the epileptic hippocampi. The changes of the dendritic arborisation were analyzed on camera lucida drawings of segments of CA1 region of controls and each epileptic type. All cells of the selected areas of 2–4 sections were drawn at high magnification and branchpoints of each cell were counted individually.

In the non-sclerotic epileptic cases (mild and patchy) the numbers and distribution of SPR-immunolabelled interneurons were similar to the control, whereas in the sclerotic samples significantly fewer positive cells were detectable (Figs. 1, 3). Numerous, shorter, often beaded and distorted dendrites are typical of the epileptic hippocampi. The segmentation of dendrites can be observed both in the non-sclerotic and sclerotic cases (Fig. 2D–E), however, in the sclerotic tissue the curved and varicose dendrites are considerably shorter and often take on a horizontal orientation (Fig. 2F–G).

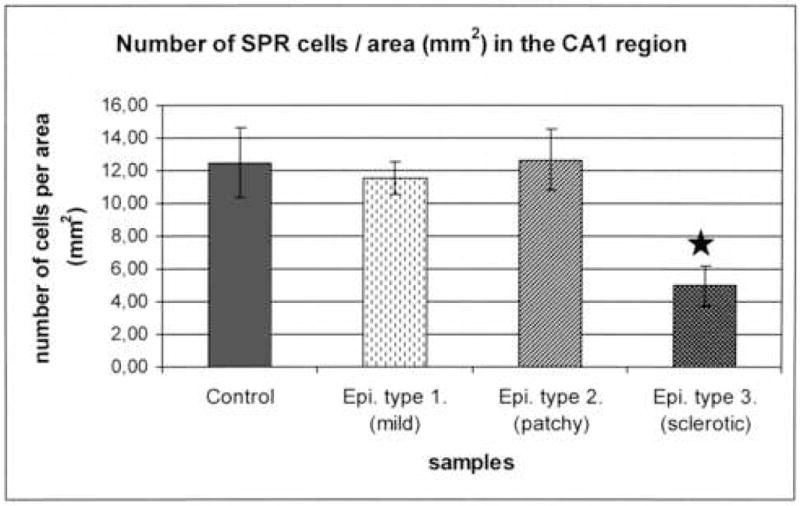

Figure 3.

Number of SPR-immunoreactive cells per unit area was examined in the CA1 region of controls and in each epileptic type. The number of SPR-positive cells remained unchanged in the non-sclerotic samples with mild and patchy pyramidal cell loss (12.5 ± 2.14 in control, 11.53 ± 1.01 in type 1. and 12.68 ± 1.84 in type 2.). However, there was a considerable decrease in the number of SPR-labelled cells in the sclerotic cases despite the shrinkage of the sclerotic CA1 region (4.97 ± 1.25). (Star labels significant difference, p<0.05).

The observations on the changes of the dendritic arborisation were quantified (Table 2). On the camera lucida drawings of the cells the total number of branchpoints per cell was counted. The number of dendritic branchpoints is increased in the non-sclerotic epileptic cases compared to the controls. This increase was statistically significant in the epileptic samples with patchy cell loss.

Table 2.

Number of dendritic branchpoints per SPR-immunoreactive interneuron in control and epileptic samples with different degrees of sclerosis. Star labels significant change in the case of the patchy samples (p < 0.05).

| Number of dendritic branchpoints per cell (mean ± stdev) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Number of cells analysed | str. oriens | str. pyramidale + radiatum |

| Control (n=33) | 4.25 ± 1.04 | 10.52 ± 3.28 |

| Mild type (n=30) | 6.63 ± 2.88 | 11.59 ± 4.62 |

| Patchy type (n=28) | * 7.25 ± 1.91 | * 21.15 ± 4.68 |

| Sclerotic type (n=18) | str. oriens + pyramidale + radiatum 3.22 ± 1.26 |

|

Furthermore, in the non-sclerotic samples, especially in the patchy type, the dendritic arbour of the cells is more complex than in controls. In the sclerotic cases the average number of dendrites per cells is decreased compared to the control values (Table 2).

Colocalization of SPR and markers of functionally different interneuron types

Since SPR-immunocytochemistry does not result in axonal staining, colocalization studies were carried out to reveal the functional type of these cells in the hippocampal inhibitory network. Several of these markers identify interneuron types with well-characterised input-output connectivity and roles in the circuitry.

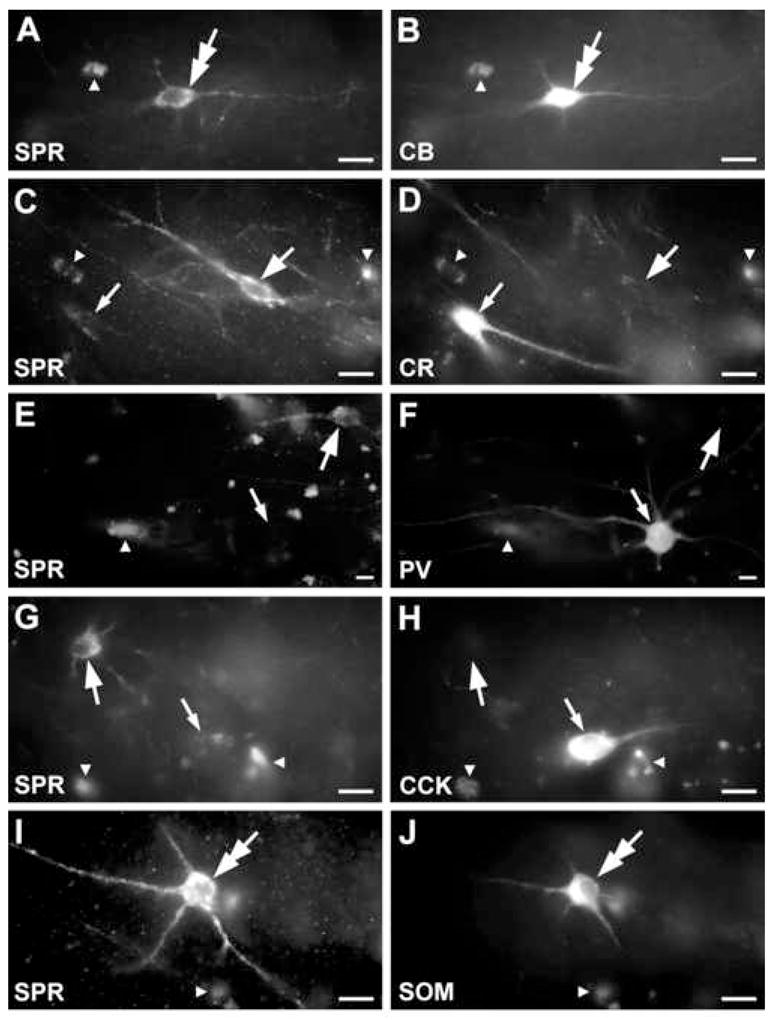

Using fluorescent double stainings we examined the overlap of SPR with calcium binding proteins calbindin (CB), parvalbumin (PV), calretinin (CR), and the neuropeptides somatostatin (SOM) and cholecystokinin (CCK) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Fluorescent light micrographs showing the colocalization of SPR and different calcium binding proteins and neuropeptides in the CA1 region of the control hippocampus. Autofluorescence of cytoplasmic granules could be easily distinguished from the more homogenous specific labelling. A-B: Double immunofluorescence staining reveals colocalization of SPR with CB in a cell (double arrow). C-D: SPR (thick arrow) does not show colocalization with the calcium binding protein CR (thin arrow). E-F: SPR-positive cells do not contain PV (thick arrow) and the PV-immunolabelled cell does not contain SPR (thin arrow). G-H: The SPR-immunoreactive cell body is CCK-negative (thick arrow) and the CCK-positive one (thin arrow) is SPR-negative. I-J: Double arrow labels the coexistence of SPR and SOM in a cell body. Small white arrowheads indicate autofluorescent lipofuscin granules used as landmarks. Scale: 20 μm.

In the human hippocampus the vast majority of CB-positive cells proved to be dendritic inhibitory interneurons (Sloviter et al., 1991, Seress et al., 1993). Recently the possible presence of CB was also shown in an axo-axonic cell type in control human CA1 (Wittner et al., 2002). PV-immunoreactive interneurons are known to be involved in the perisomatic inhibition of principal cells (Braak et al., 1991, Seress et al., 1993), CR labels dendritic and interneuron specific inhibitory cells (Urban et al., 2002). SOM is a marker for dendritic inhibitory interneurons according to the distribution of the SOM-positive axons in the CA1 region (Chan-Palay, 1987). CCK is likely present both in perisomatic and dendritic inhibitory interneurons (Lotstra and Vanderhaeghen, 1987, Katona et al., 2000).

SPR-immunoreactive interneurons were not observed to express CCK in our samples. The SPR-positive interneurons showed poor colocalization with other neuropeptides or calcium binding proteins (Table 3, Fig. 4). The largest colocalization was seen with CB: 8.7 % of the SPR-immunolabelled interneurons were positive for calbindin in the CA1 region, whereas 20.8 % of the CB-positive interneurons have shown SPR-immunopositivity as well. However, most SPR-immunoreactive cells do not show colocalization with the examined markers, the majority of this interneuron population can be visualized only with SPR-immunostaining.

Table 3.

Colocalization of SPR and other neurochemical markers in the control human hippocampus.

| In proportion of SPR-positive cells | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CB | PV | CR | SOM | CCK | |

| Number of SPR-positive cells examined | 325 | 524 | 335 | 566 | 217 |

| Proportion of cells double- labelled for markers | 8.7 % | 4 % | 2.6 % | 3.4 % | 0 % |

| In proportion of marker-positive cells | |||||

| Number of marker-positive cells examined | CB 190 | PV 281 | CR 280 | SOM 188 | CCK 103 |

| Proportion of cells double- labelled for SPR | 20,8 % | 7.3 % | 2.6 % | 7.8 % | 0 % |

Since in the control tissue SPR-positive interneurons showed the largest colocalization with CB, in the epileptic samples we examined the overlap only with this marker. SOM-immunoreactive cells, which showed the highest ratio of colocalization beside CB, were not tested because they nearly disappear from the epileptic human hippocampus (de Lanerolle et al., 1987).

Our results show that the ratio of the CB-containing SPR-cells (8.7 % in control) remained unchanged in the mild type (9.6 %), but increased in the tissues with patchy pyramidal cell loss and strong sclerosis (14.5 % and 16.9 %, respectively). Furthermore, the ratio of SPR-positive CB-interneurons increased in all epileptic samples (Table 4).

Table 4.

Colocalization of SPR and CB in the epileptic human hippocampus.

| In proportion of SPR-positive cells | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Epileptic Type 1 (mild) | Epileptic Type 2 (patchy) | Epileptic Type 3 (sclerotic) | |

| Number of SPR-positive cells examined | 860 | 642 | 896 | 245 |

| Proportion of cells double- labelled for CB | 8.7 % | 9.6 % | 14,5 % | 16.9 % |

| In proportion of CB-positive cells | ||||

| Control | Epileptic Type 1 (mild) | Epileptic Type 2 (patchy) | Epileptic Type 3 (sclerotic) | |

| Number of CB- positive interneurons examined | 424 | 162 | 426 | 173 |

| Proportion of cells double- labelled for SPR | 20,8 % | 38.2 % | 23,7 % | 32.2 % |

Examination of the input characteristics of the SPR-immunoreactive cells

Electron microscopic studies were carried out to reveal whether the synaptic input characteristics of the SPR-immunoreactive elements changed in the epileptic tissues. We have examined 2 control and 8 epileptic samples (2 mild, 3 patchy, 3 sclerotic patients). From each samples str. oriens, pyramidale and radiatum were reembedded from the CA1 region. In the sclerotic cases the strata oriens, pyramidale and radiatum were not separable, therefore they were pooled.

Ultrastructural features of the SPR-immunoreactive elements

The receptor is located on all parts of the somatic and dendritic membrane. SPR-immunoreactivity is mainly concentrated on the plasma membrane, but some cytoplasmic labelling was also apparent presumably showing sites of receptor synthesis. Because of the diffusibility of the DAB reaction end product, in some cases it filled the entire dendritic shaft (Fig. 5). The cytoplasmic rim around the infolded nucleus was usually thin, but contained numerous mitochondria. SPR-immunolabelled axons or axon terminals were not found among the examined profiles.

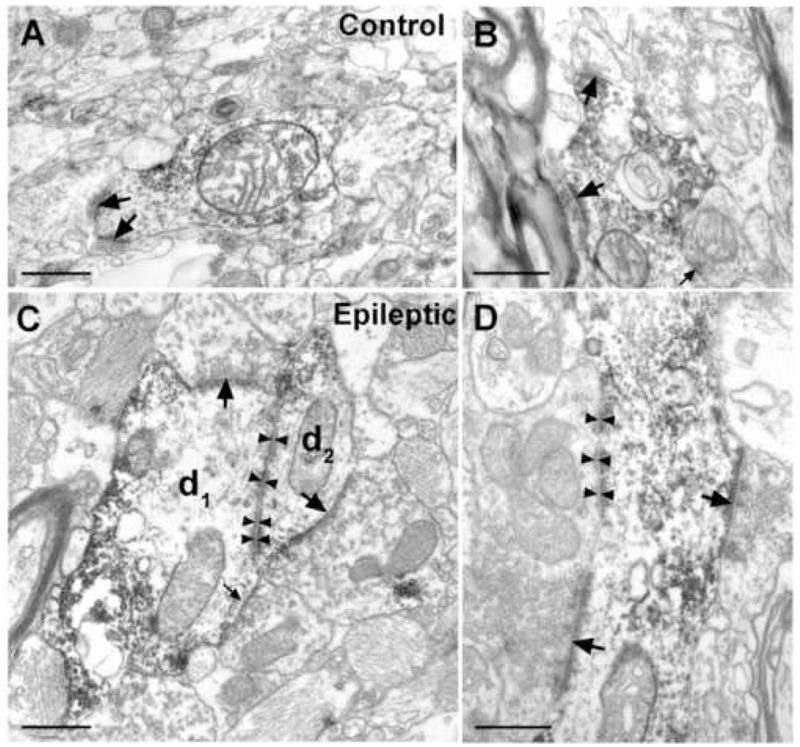

Figure 5.

Electron micrographs showing SPR-immunolabelled dendrites from control (A, B) and sclerotic epileptic (C, D) human samples. They receive numerous, mainly asymmetric synaptic inputs (A, B, C, D, thick arrows). Lower proportion of the synapses was symmetric (B, C, thin arrows). Zonula adherentia is present between d1 and d2 (C, arrowheads). Large synapses with multiple puncta adherentia (mossy fibre-like) can be often observed in the epileptic tissue (D, thick arrows, arrowheads). Scale: 1 μm.

The synaptic contacts were confined to the dendrites of SPR-positive cells, we failed to observe any synaptic input on their somata (over 30 SPR-positive cell bodies have been examined in single sections). The symmetric and asymmetric contacts were distinguishable on the basis of the postsynaptic density. The majority (approx. 90 %) of the synaptic inputs on the dendritic shafts were asymmetric, presumed excitatory contacts. Symmetric, presumed inhibitory inputs were less frequently seen both in control and epileptic samples (Fig. 5). Occasionally, zonula adherentia-type contacts occurred between SPR-immunoreactive dendrites in epileptic cases (Fig. 5C), but not in control samples.

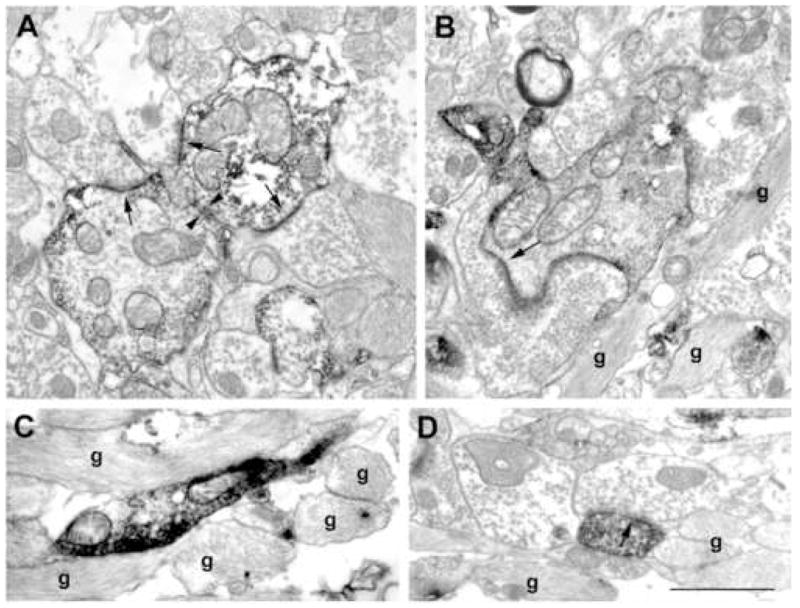

In the epileptic samples the mass of the glial elements increased compared to the controls (Fig. 6B,C,D). SPR-immunoreactive dendrites usually received numerous synaptic contacts in the epileptic tissues, but shafts covered with glial processes on their entire surface were also observed in the sclerotic samples. Large, mossy-like terminals frequently surrounded the SPR-positive profiles in the epileptic tissue, especially in the sclerotic cases. They established asymmetric synapses usually with long synaptic active zones (Fig. 6A,B,D). Degenerating immunopositive dendritic shafts were also often observed in the sclerotic cases, with degrading mitochondria and cytoplasmic matrix.

Figure 6.

Electron micrographs from the CA1 region of sclerotic samples. The length of the synaptic active zones increased in the sclerotic tissue (A, B, D, arrows). Dendro-dendritic contacts (A, arrowheads) and SPR-positive elements surrounded by astrocytes (B, C, D) were frequently seen. SPR-positive dendrites contacted by large, mossy-like terminals were rarely seen (B, D). g: glia Scale: 1 μm.

Synaptic coverage

To investigate whether SPR-immunoreactive cells are affected by synaptic reorganization, we examined the synaptic coverage of SPR-positive cells in the control and epileptic samples. All dendritic shafts of each sample area were measured in the study, independent of the characteristics of their synaptic input. Only shafts with well-preserved membrane boundaries were included in the study. The presence of a well visible synaptic cleft, accumulation of vesicles in the presynaptic terminal, and a detectable postsynaptic density were taken as criteria for the identification of a synapse. The differentiation of symmetric and asymmetric synapses was based on the thickness of the postsynaptic density.

In the control CA1 region SPR-immunoreactive interneuron dendrites receive mainly asymmetric (presumed excitatory) synapses, whereas symmetric (presumed inhibitory) synaptic contacts were rarely seen (Fig. 5). In the epileptic samples the vast majority of the synapses were asymmetric, like in the control tissue.

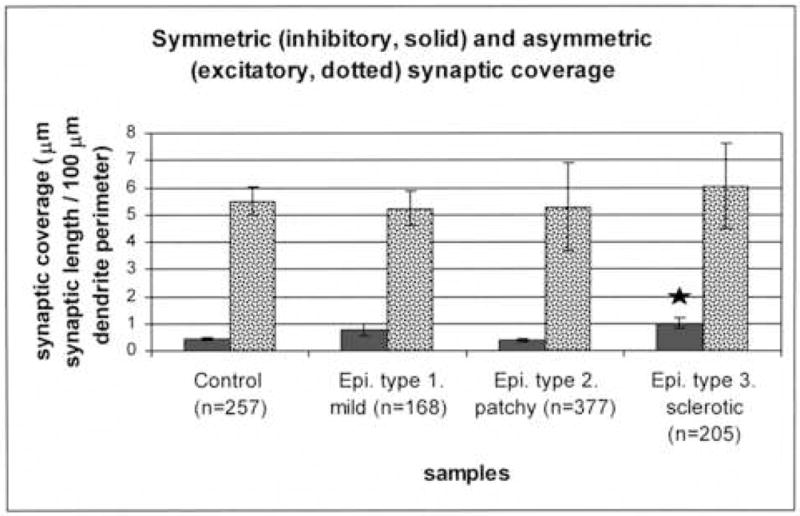

We examined whether the degree of synaptic coverage and the ratio of symmetric and asymmetric inputs on the SPR-immunostained dendritic shafts have changed. The perimeter of SPR-positive interneuron dendrites and the length of symmetric and asymmetric synapses were measured and synaptic coverage (μm synaptic length/100 μm of dendrite perimeter) was determined. Our results show that the total synaptic coverage (including symmetric + asymmetric) remain unchanged in all types of the epileptic samples. We could not detect any laminar difference between str. oriens, pyramidale and radiatum neither in control nor in epileptic tissues. Although the total synaptic coverage was not altered, the ratio of the symmetric synapses considerably increased in the sclerotic epileptic tissue (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

The synaptic coverage of the SPR-immunoreactive dendrites in control and epileptic tissues. The perimeter of SPR-positive interneuron dendrites and the length of symmetric and asymmetric synapses were measured and synaptic coverage (μm synaptic length/100 μm of dendrite perimeter) was determined. The asymmetric synaptic coverage did not change in the epileptic samples. However, there was a significant increase in the symmetric (presumably inhibitory) synaptic coverage in case of the sclerotic samples. The numbers of the examined dendritic profiles are presented in parenthesis. (Star labels significant difference, p<0.05).

Length of synaptic active zones

We examined the length of the synaptic active zones in each layer in the control and epileptic samples. The length of the synaptic active zones remained unchanged in the str. pyramidale and radiatum. However, in the case of the asymmetric synapses it was increased in the str. oriens of the epileptic cases even in the mild type (Fig. 6).

Discussion

SPR-positive interneurons participate in dendritic inhibition in the human hippocampus

SPR-positive cells of the human hippocampus are considerably different from the same neurochemically identified cell type described in rats. SPR stains the soma-dendritic compartment of a functionally heterogeneous cell group in the rat hippocampus and relatively high degrees of colocalization were shown with numerous other neurochemical markers of interneurons (Acsady et al., 1997, Sloviter et al., 2001). In contrast, in the human hippocampus, our double immunofluorescence studies showed only a small overlap with the dendritic inhibitory cell marker calbindin, and we could not demonstrate a considerable colocalization with other dendritic (CCK, SOM, CR), perisomatic (PV) or interneuron selective (CR) inhibitory cell markers (Table 3, Fig. 4). These results suggest that part of the SPR-immunoreactive cells participate in dendritic inhibition of hippocampal principal cells. Since the majority of SPR-positive interneurons could not be visualized by any markers other than SPR, the question remains whether the majority of these cells participate in dendritic, perisomatic or interneuron selective inhibitory networks in the human hippocampus.

We have shown a considerable colocalization of SPR and CB in interneurons of the human CA1 region, and this ratio of double-labelled cells has increased in the epileptic samples (Table 4). CB-positive interneurons were found to be resistant to epileptic damage both in humans (Sloviter et al., 1991, Magloczky et al., 2000, Suckling et al., 2000, Wittner et al., 2002) and in rat models of epilepsy (Sloviter, 1989, Freund et al., 1992, Magloczky and Freund, 1993, Bouilleret et al., 2000). The increase in the ratio of CB/SPR double-labelled interneurons suggests that the CB-positive subtype of SPR-immunoreactive cells might be more resistant in epilepsy than CB-negative ones.

SPR-positive interneurons survive in the human epileptic CA1 region with an altered morphology

In this study we demonstrated that SPR-immunoreactive interneurons are preserved in the human epileptic CA1 region: their number and distribution was similar to control in the non-sclerotic (mild and patchy) cases (Fig. 1), although their number was reduced in the sclerotic samples (Fig. 3). However, the morphology of individual cells has considerably changed in the epileptic tissue. In the non-sclerotic cases, the dendrites of SPR-immunostained interneurons became beaded, and quantitative analysis demonstrated their remarkable extension (Fig. 2, Table 2). This morphological alteration can be provoked through different mechanisms. Dendrites of SPR-expressing neurons in cell culture became varicose, when SP was delivered in high concentration (Mantyh et al., 1995). Both intra- and extrahippocampal sources may deliver SP in the control human hippocampus; SP-containing interneurons are abundant in all regions (Lotstra et al., 1988), and the axon bundle originating from the supramammillary nucleus, and terminating in the dentate molecular layer and the CA2 region also contains SP (Davies and Kohler, 1985, Ino et al., 1988, Yanagihara and Niimi, 1989, Nitsch and Leranth, 1994b). Hippocampal principal cells were shown to dramatically increase their SP-expression in animal models of epilepsy (Liu et al., 1999b, Liu et al., 2000, Wasterlain et al., 2000). In addition the supramammillo-hippocampal pathway, - which is considered the main source of SP to the hippocampus – was found to sprout in human epilepsy (Magloczky et al., 2000). Taken together, an increase in the levels of SP is the most likely facer responsible for the beaded appearance of SPR-positive interneuron dendrites in the human epileptic hippocampus.

An alternative explanation of the presence of varicose dendrites might be excitotoxic injury. This is supported by the presence of degenerating SPR-immunolabelled elements in the sclerotic CA1 region (Fig. 6), as well as by the finding that in the sclerotic epileptic cases the number of SPR-positive interneurons has considerably decreased (Fig. 3). The decrease of dendritic branchpoints of SPR-immunoreactive cells in the sclerotic CA1 region further confirms this hypothesis (Table 2).

The large number of short, distorted, varicose dendrites are the characteristics of immature neurons (Seress and Ribak, 1990, Seay-Lowe and Claiborne, 1992), which might be induced by neurotrophins also in epilepsy, in a similar way as during development. The level of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (Mathern et al., 1997b, Poulsen et al., 2004) as well as its specific receptor, TrkB (Rocamora et al., 1992, Dugich-Djordjevic et al., 1995, Goutan et al., 1998), was shown to be increased after epileptic activity. BDNF was also demonstrated to improve survival and differentiation of CB-containing interneurons during development (Lowenstein and Arsenault, 1996, Pappas and Parnavelas, 1997, Fiumelli et al., 2000). Since CB-positive SPR-immunoreactive interneurons are preserved in all epileptic samples, we hypothesise that increased levels of BDNF may promote their survival and the extension of their dendritic tree. It should be noted, however that extension of the dendritic tree of SPR-expressing inhibitory cells may serve to compensate for the excitatory effect caused by the increased level of SP in epileptic tissue.

Synaptic reorganization in the human epileptic CA1 region

Similar to CB-positive interneuron dendrites (Wittner et al., 2002), the ratio of inhibitory inputs to SPR-immunostained dendrites has significantly increased in the human sclerotic CA1 region (Fig. 7). This increase might be due to the axonal sprouting of the preserved interneurons, as it was described previously in the case of CB-positive interneurons (Wittner et al., 2002). We hypothesise that preserved interneurons with higher inhibitory input might participate in the abnormal synchrony of the CA1 region via disinhibition, and/or the higher ratio of inhibitory input of these interneurons may diminish the efficacy of dendritic inhibition of principal cells.

Similarly, mossy-like terminals were also observed in the CA1 region like in a previous study investigating calbindin-containing neurons (Wittner et al., 2002). It is possible that these terminals originate from the granule cells, and the mossy fibre system may penetrate the CA1 region in the sclerotic epileptic human hippocampus (Mathern et al., 1997a). Surviving CA2-3 pyramidal cells might also be possible sources of terminals establishing asymmetric synapses on SPR-positive dendrites in sclerotic cases.

We could not find a striking difference in the number and distribution of SPR-immunoreactive cells in the non-sclerotic cases (Fig. 3), but the morphological alteration of these cells is apparent in these samples (Figs. 1, 2, Table 2). This observation supports the hypothesis that an intense synaptic reorganization takes place in the non-sclerotic epileptic CA1 region (Lehmann et al., 2001, Wittner et al., 2002, Wittner et al., 2005) that involves interneurons, in the absence of a massive pyramidal cell loss. The dramatic changes in the morphology of SPR-positive cells may suggest an altered function and enhanced efficacy of the SP system in the epileptic human hippocampus. Therefore, the SP system may prove to be a new drug target in the pharmacotherapy of epilepsy.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Drs. M. Palkovits, P. Sótonyi and Zs. Borostyánkői (Semmelweis University, Budapest) for providing control human tissue and to F. Mátyás for the help in preparation of the figures. The excellent technical assistance of Ms. E. Simon, K. Lengyel, K. Iványi and Mr. Gy. Goda is also acknowledged. This study was supported by grants from NIH (MH 54671), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (55000307) and Szentágothai Knowledge Center. Antibody #9303 raised in mouse against CCK was provided by CURE/Digestive Diseases Research Center, Antibody/RIA Core, NIH Grant #DK41301.

Abbreviations

- BSA

Bovine serum albumin

- CA1, CA2, CA3, CA4

Hippocampal subfields according to Lorente de No

- CCK

Cholecystokinin

- CB

Calbindin

- CR

Calretinin

- DAB

3,3′Diamino-benzidine 4 HCl

- GABA

Gamma-aminobutyric acid

- PB

Phosphate buffer

- PV

Parvalbumin

- SOM

Somatostatin

- SP

Substance P

- SPR

Substance P receptor

- TB

Tris buffer

- TBS

Tris buffered saline

- TLE

Temporal lobe epilepsy

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Acsady L, Katona I, Gulyas AI, Shigemoto R, Freund TF. Immunostaining for substance P receptor labels GABAergic cells with distinct termination patterns in the hippocampus. J Comp Neurol. 1997;378:320–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babb TL, Pretorius JK, Kupfer WR, Crandall PH. Glutamate decarboxylase-immunoreactive neurons are preserved in human epileptic hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1989;9:2562–2574. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-07-02562.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borhegyi Z, Leranth C. Distinct substance P- and calretinin-containing projections from the supramammillary area to the hippocampus in rats; a species difference between rats and monkeys. Exp Brain Res. 1997a;115:369–374. doi: 10.1007/pl00005706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borhegyi Z, Leranth C. Substance P innervation of the rat hippocampal formation. The Journal of comparative neurology. 1997b;384:41–58. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970721)384:1<41::aid-cne3>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouilleret V, Schwaller B, Schurmans S, Celio MR, Fritschy JM. Neurodegenerative and morphogenic changes in a mouse model of temporal lobe epilepsy do not depend on the expression of the calcium-binding proteins parvalbumin, calbindin, or calretinin. Neuroscience. 2000;97:47–58. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak E, Strotkamp B, Braak H. Parvalbumin-immunoreactive structures in the hippocampus of the human adult. Cell Tissue Res. 1991;264:33–48. doi: 10.1007/BF00305720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carre GP, Harley CW. Population Spike Facilitation in the Dentate Gyrus Following Glutamate to the Lateral Supramammillary Nucleus. Brain Res. 1991;568:307–310. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91415-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan-Palay V. Somatostatin immunoreactive neurons in the human hippocampus and cortex shown by immunogold/silver intensification on vibratome sections: coexistence with neuropeptide Y neurons, and effects in Alzheimer-type dementia. J Comp Neurol. 1987;260:201–223. doi: 10.1002/cne.902600205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies S, Kohler C. The substance P innervation of the rat hippocampal region. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1985;173:45–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00707303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lanerolle NC, Kim JH, Williamson A, Spencer SS, Zaveri HP, Eid T, Spencer DD. A retrospective analysis of hippocampal pathology in human temporal lobe epilepsy: evidence for distinctive patient subcategories. Epilepsia. 2003;44:677–687. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.32701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lanerolle NC, Sloviter RS, Kim JH, Robbins RJ, Spencer DD. Evidence for hippocampal interneuron loss in human temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1988;29:674. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90234-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lanerolle NC, Thapar K, Partington JP, Robbins RJ. Comparison of somatostatin immunoreactivity in epileptogenic and normal human hippocampi. Epilepsia. 1987;28:600–601. [Google Scholar]

- Duggan AW, Hope PJ, Jarrott B, Schaible HG, Fleetwood-Walker SM. Release, spread and persistence of immunoreactive neurokinin A in the dorsal horn of the cat following noxious cutaneous stimulation. Studies with antibody microprobes. Neuroscience. 1990;35:195–202. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90134-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugich-Djordjevic MM, Ohsawa F, Okazaki T, Mori N, Day JR, Beck KD, Hefti F. Differential regulation of catalytic and non-catalytic trkB messenger RNAs in the rat hippocampus following seizures induced by systemic administration of kainate. Neuroscience. 1995;66:861–877. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00631-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiumelli H, Kiraly M, Ambrus A, Magistretti PJ, Martin JL. Opposite regulation of calbindin and calretinin expression by brain-derived neurotrophic factor in cortical neurons. J Neurochem. 2000;74:1870–1877. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0741870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund TF, Ylinen A, Miettinen R, Pitkanen A, Lahtinen H, Baimbridge KG, Riekkinen PJ. Pattern of neuronal death in the rat hippocampus after status epilepticus. Relationship to calcium binding protein content and ischemic vulnerability. Brain Res Bull. 1992;28:27–38. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(92)90227-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goutan E, Marti E, Ferrer I. BDNF, and full length and truncated TrkB expression in the hippocampus of the rat following kainic acid excitotoxic damage. Evidence of complex time-dependent and cell-specific responses. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1998;59:154–164. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00156-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houser CR. Neuronal loss and synaptic reorganization in temporal lobe epilepsy. Adv Neurol. 1999;79:743–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houser CR, Swartz BE, Walsh GO, Delgado-Escueta AV. Granule cell disorganization in the dentate gyrus: possible alterations of neuronal migration in human temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Res Suppl. 1992;9:41–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ino T, Itoh K, Sugimoto T, Kaneko T, Kamiya H, Mizumo N. The supramammillary region of the cat sends substance P-like immunoreactive axons to the hippocampal formation and the entorhinal cortex. Neurosci Lett. 1988;90:259–264. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90199-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katona I, Sperlagh B, Magloczky Z, Santha E, Kofalvi A, Czirjak S, Mackie K, Vizi ES, Freund TF. GABAergic interneurons are the targets of cannabinoid actions in the human hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2000;100:797–804. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00286-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyama H, Maeno H, Tohyama M. Substance P receptor (NK-1) in the central nervous system:possible functions from a morphological aspect. RegulPept. 1993;46:114–123. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(93)90021-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann TN, Gabriel S, Eilers A, Njunting M, Kovacs R, Schulze K, Lanksch WR, Heinemann U. Fluorescent tracer in pilocarpine-treated rats shows widespread aberrant hippocampal neuronal connectivity. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14:83–95. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leranth C, Nitsch R. Morphological evidence that hypothalamic substance P-containing afferents are capable of filtering the signal flow in the monkey hippocampal formation. J Neurosci. 1994;14:4079–4094. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-07-04079.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Brown JL, Jasmin L, Maggio JE, Vigna SR, Mantyh PW, Basbaum AI. Synaptic relationship between substance P and the substance P receptor: light and electron microscopic characterization of the mismatch between neuropeptides and their receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:1009–1013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.3.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Cao Y, Basbaum AI, Mazarati AM, Sankar R, Wasterlain CG. Resistance to excitotoxin-induced seizures and neuronal death in mice lacking the preprotachykinin A gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999a;96:12096–12101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Mazarati AM, Katsumori H, Sankar R, Wasterlain CG. Substance P is expressed in hippocampal principal neurons during status epilepticus and plays a critical role in the maintenance of status epilepticus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999b;96:5286–5291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Sankar R, Shin DH, Mazarati AM, Wasterlain CG. Patterns of status epilepticus-induced substance P expression during development. Neuroscience. 2000;101:297–304. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00383-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotstra F, Mailleux P, Vanderhaeghen JJ. Substance P neurons in the human hippocampus: an immunohistochemical analysis in the infant and adult. J Chem Neuroanat. 1988;1:111–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotstra F, Vanderhaeghen JJ. Distribution of immunoreactive cholecystokinin in the human hippocampus. Peptides. 1987;8:911–920. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(87)90080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loup F, Wieser HG, Yonekawa Y, Aguzzi A, Fritschy JM. Selective alterations in GABAA receptor subtypes in human temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5401–5419. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-14-05401.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein DH, Arsenault L. The effects of growth factors on the survival and differentiation of cultured dentate gyrus neurons. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1759–1769. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-05-01759.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magloczky Z, Acsady L, Freund TF. Principal cells are the postsynaptic targets of supramammillary afferents in the hippocampus of the rat. Hippocampus. 1994;4:322–334. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450040316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magloczky Z, Freund TF. Selective neuronal death in the contralateral hippocampus following unilateral kainate injections into the CA3 subfield. Neuroscience. 1993;56:317–335. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90334-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magloczky Z, Freund TF. Impaired and repaired inhibitory circuits in the epileptic human hippocampus. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magloczky Z, Wittner L, Borhegyi Z, Halasz P, Vajda J, Czirjak S, Freund TF. Changes in the distribution and connectivity of interneurons in the epileptic human dentate gyrus. Neuroscience. 2000;96:7–25. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00474-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantyh PW, Allen CJ, Ghilardi JR, Rogers SD, Mantyh CR, Liu H, Basbaum AI, Vigna SR, Maggio JE. Rapid endocytosis of a G protein-coupled receptor: substance P-evoked internalization of its receptor in the rat striatum in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2622–2626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathern GW, Babb TL, Armstrong DL. Hippocampal Sclerosis. In: Engel JJ, Pedley TA, editors. Epilepsy: A Comprehensive Textbook. Vol. 13. Philadelphia: Lipincott-Raven; 1997a. pp. 133–155. [Google Scholar]

- Mathern GW, Babb TL, Micevych PE, Blanco CE, Pretorius JK. Granule cell mRNA levels for BDNF, NGF, and NT-3 correlate with neuron losses or supragranular mossy fiber sprouting in the chronically damaged and epileptic human hippocampus. Mol Chem Neuropathol. 1997b;30:53–76. doi: 10.1007/BF02815150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathern GW, Babb TL, Pretorius JK, Leite JP. Reactive synaptogenesis and neuron densities for neuropeptide Y, somatostatin, and glutamate decarboxylase immunoreactivity in the epileptogenic human fascia dentata. J Neurosci. 1995;15:3990–4004. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03990.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maubach KA, Cody C, Jones RS. Tachykinins may modify spontaneous epileptiform activity in the rat entorhinal cortex in vitro by activating GABAergic inhibition. Neuroscience. 1998;83:1047–1062. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00469-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizumori SJY, Mcnaughton BL, Barnes CA. A comparison of supramammillary and medial septal influences on hippocampal field potentials and single unit activity. J Neurophysiol. 1989;61:15–31. doi: 10.1152/jn.1989.61.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaya YT, Kaneko R, Shigemoto R, Nakanishi S, Mizuno N. Immunohistochemical localization of substance P receptor in the central nervous system of the adult rat. J Comp Neurol. 1994;347:249–274. doi: 10.1002/cne.903470208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawa H, Kotani H, Nakanishi S. Tissue-specific generation of two preprotachykinin mRNAs from one gene by alternative RNA splicing. Nature. 1984;312:729–734. doi: 10.1038/312729a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsch R, Leranth C. Sprouting of remaining substance P-immunoreactive fibers in the monkey dentate gyrus following denervation from its substance P-containing hypothalamic afferents. Exp Brain Res. 1994a;100:522–526. doi: 10.1007/BF02738412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsch R, Leranth C. Substance P-containing hypothalamic afferents to the monkey hippocampus: an immunocytochemical, tracing, and coexistence study. Exp Brain Res. 1994b;101:231–240. doi: 10.1007/BF00228743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogier R, Raggenbass M. Action of tachykinins in the rat hippocampus: modulation of inhibitory synaptic transmission. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:2639–2647. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas IS, Parnavelas JG. Neurotrophins and basic fibroblast growth factor induce the differentiation of calbindin-containing neurons in the cerebral cortex. Exp Neurol. 1997;144:302–314. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen FR, Lauterborn J, Zimmer J, Gall CM. Differential expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor transcripts after pilocarpine-induced seizure-like activity is related to mode of Ca2+ entry. Neuroscience. 2004;126:665–676. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratzliff AH, Santhakumar V, Howard A, Soltesz I. Mossy cells in epilepsy: rigor mortis or vigor mortis? Trends in neurosciences. 2002;25:140–144. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)02122-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocamora N, Palacios JM, Mengod G. Limbic seizures induce a differential regulation of the expression of nerve growth factor, brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neurotrophin-3, in the rat hippocampus. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1992;13:27–33. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(92)90041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seay-Lowe SL, Claiborne BJ. Morphology of intracellularly labeled interneurons in the dentate gyrus of the immature rat. J Comp Neurol. 1992;324:23–36. doi: 10.1002/cne.903240104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seress L, Gulyas AI, Ferrer I, Tunon T, Soriano E, Freund TF. Distribution, morphological features, and synaptic connections of parvalbumin- and calbindin D28k-immunoreactive neurons in the human hippocampal formation. J Comp Neurol. 1993;337:208–230. doi: 10.1002/cne.903370204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seress L, Ribak CE. Postnatal development of the light and electron microscopic features of basket cells in the hippocampal dentate gyrus of the rat. Anat Embryol. 1990;181:547–565. doi: 10.1007/BF00174627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigemoto R, Nakaya YT, Nomura S, Ogawa-Meguro R, Ohishi H, Kaneko T, Nakanishi S, Mizuno N. Immunocytochemical localization of rat substance P receptor in striatum. Neurosci Lett. 1993;153:157–160. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90311-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloviter RS. Calcium-binding protein (Calbindin-D28k) and parvalbumin immunocytochemistry: localization in the rat hippocampus with specific reference to the selective vulnerability of hippocampal neurons to seizure activity. J Comp Neurol. 1989;280:183–196. doi: 10.1002/cne.902800203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloviter RS, Ali-Akbarian L, Horvath KD, Menkens KA. Substance P receptor expression by inhibitory interneurons of the rat hippocampus: enhanced detection using improved immunocytochemical methods for the preservation and colocalization of GABA and other neuronal markers. J Comp Neurol. 2001;430:283–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloviter RS, Sollas AL, Barbaro NM, Laxer KD. Calcium-binding protein (calbindin-D28K) and parvalbumin immunocytochemistry in the normal and epileptic human hippocampus. J Comp Neurol. 1991;308:381–396. doi: 10.1002/cne.903080306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer DD, Spencer SS. Surgery for epilepsy. Neurol Clin. 1985;3:313–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey AE, Woodhall GL, Jones RS. Activation of neurokinin-1 receptors promotes GABA release at synapses in the rat entorhinal cortex. Neuroscience. 2002;115:575–586. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00412-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suckling J, Roberts H, Walker M, Highley JR, Fenwick P, Oxbury J, Esiri MM. Temporal lobe epilepsy with and without psychosis: exploration of hippocampal pathology including that in subpopulations of neurons defined by their content of immunoreactive calcium-binding proteins. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2000;99:547–554. doi: 10.1007/s004010051159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutula TP, Cascino G, Cavazos JE, Ramirez L. Mossy fiber synaptic reorganization in the epileptic human temporal lobe. Ann Neurol. 1989;26:321–330. doi: 10.1002/ana.410260303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban Z, Magloczky Z, Freund TF. Calretinin-containing interneurons innervate both principal cells and interneurons in the CA1 region of the human hippocampus. Acta Biol Hung. 2002;53:205–220. doi: 10.1556/ABiol.53.2002.1-2.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vertes RP. PHA-L analysis of projections from the supramammillary nucleus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1992;326:595–622. doi: 10.1002/cne.903260408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasterlain CG, Liu H, Mazarati AM, Baldwin RA, Shirasaka Y, Katsumori H, Thompson KW, Sankar R, Pereira de Vasconselos A, Nehlig A. Self-sustaining status epilepticus: a condition maintained by potentiation of glutamate receptors and by plastic changes in substance P and other peptide neuromodulators. Epilepsia 41 Suppl. 2000;6:S134–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb01572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittner L, Eross L, Czirjak S, Halasz P, Freund TF, Magloczky Z. Surviving CA1 pyramidal cells receive intact perisomatic inhibitory input in the human epileptic hippocampus. Brain. 2005;128:138–152. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittner L, Eross L, Szabo Z, Toth S, Czirjak S, Halasz P, Freund TF, Magloczky ZS. Synaptic reorganization of calbindin-positive neurons in the human hippocampal CA1 region in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuroscience. 2002;115:961–978. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00264-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittner L, Magloczky Z, Borhegyi Z, Halasz P, Toth S, Eross L, Szabo Z, Freund TF. Preservation of perisomatic inhibitory input of granule cells in the epileptic human dentate gyrus. Neuroscience. 2001;108:587–600. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00446-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagihara M, Niimi K. Substance P-like immunoreactive projection to the hippocampal formation from the posterior hypothalamus in the cat. Brain Res Bull. 1989;22:689–694. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(89)90088-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachrisson O, Lindefors N, Brene S. A tachykinin NK1 receptor antagonist, CP-122,721-1, attenuates kainic acid-induced seizure activity. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1998;60:291–295. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]