Abstract

The enzymes of the KsgA/Dim1 family are universally distributed throughout all phylogeny; however, structural and functional differences are known to exist. The well-characterized function of these enzymes is to dimethylate two adjacent adenosines of the small ribosomal subunit in the normal course of ribosome maturation and the structures of KsgA from Escherichia coli and Dim1 from Homo sapiens and Plasmodium falciparum have been determined. To this point no examples of archaeal structures have been reported. Here we report the structure of Dim1 from the thermophilic archaeon Methanocaldococcus jannaschii. While it shares obvious similarities with the bacterial and eukaryotic orthologs, notable structural differences exist among the three members, particularly in the C-terminal domain. Previous work showed that eukaryotic and archaeal Dim1 were able to robustly complement for KsgA in E. coli. Here we repeated similar experiments to test for complementarity of archaeal Dim1 and bacterial KsgA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. However, neither the bacterial nor the archaeal ortholog could complement for the eukaryotic Dim1. This might be related to the secondary, non-methyltransferase function that Dim1 is known to play in eukaryotic ribosomal maturation. To further delineate regions of the eukaryotic Dim1 critical to its function, we created and tested KsgA/Dim1 chimeras. Of the chimeras, only one constructed with the N-terminal domain from eukaryotic Dim1 and the C-terminal domain from archaeal Dim1 was able to complement, suggesting that eukaryotic-specific Dim1 function resides in the N-terminal domain also, where few structural differences are observed between members of the KsgA/Dim1 family. Future work is required to identify those determinants directly responsible for Dim1 function in ribosome biogenesis. Finally, we have conclusively established that none of the methyl groups are critically important to growth in yeast under standard conditions at a variety of temperatures.

Keywords: Dim1, KsgA, Archaea, dimethyltransferase, rRNA methylation

Introduction

During the biogenesis of ribosomes two adjacent adenosines of small subunit rRNA are converted into N6, N6-dimethyladenosines by a universally conserved group of orthologous methyltransferases. In bacteria, this methyltransferase is known as KsgA, a name based on its involvement with resistance to the antibiotic kasugamycin.1,2 KsgA confers sensitivity to the antibiotic kasugamycin by directly methylating 16S rRNA; cells that lack active KsgA are resistant to the same antibiotic.3 In eukaryotic and archaeal organisms this dimethyltrasferase is referred as Dim1.4,5 Remarkably, the KsgA/Dim1 family is one of only about 50 factors conserved in all life, thus implicating it as a member of the last universal common ancestor (LUCA), perhaps the only ribosome biogenesis factor with this distinction.6

Members of the KsgA/Dim1 family have adopted additional roles in ribosome biogenesis as individual members diverged from their common ancestor. In E. coli, KsgA serves as a non-essential gate-keeper to ensure assembly fidelity.7,8 Eukaryotic Dim1, in addition to its dimethyltransferase role, is an essential member of the processome,9,10 a multi-factor complex required for pre-rRNA processing at sites A0, A1, and A2. However, no specific details of how Dim1 contributes to the function of the processome are known. Mitochondria have their own ribosomes, which in many species, including humans, are likewise dimethylated at the tandem adenosines. The responsible enzyme in this case is a nuclear encoded protein termed mtTFB for its previously described role as a mitochondrial transcription factor.11

We have recently shown through in vivo and in vitro studies that eukaryotic and archaeal Dim1 enzymes are able to complement for KsgA’s dimethyltransferase function in E. coli.5 Such complementation implies a conservation of structural determinants involved in binding of the protein to its ribosomal substrate. However, it is not known whether functional complementation extends in other directions, for example, whether bacterial KsgA and archaeal Dim1 can complement for loss of Dim1 in eukaryotes (S. Cerevisiae).

Three members of the KsgA/Dim1 family have had their three-dimensional structures determined; KsgA from E. coli and Dim1 from both H. sapiens (unpublished deposition) and P. falciparum.12,13 The greatest gap in our knowledge comes from the fact that no archaeal ortholog has had its structure determined. We previously reported an alignment of KsgA/Dim1 orthologs that included the Dim1 sequence from the archaeon M. jannaschii, but sequence homology in parts of the C-terminal domain was too poor to confidently trust alignments without having a three-dimensional structure as a guide.5

Here we report the crystal structure of Dim1 from M. jannaschii. Additionally, we have extended our previous complementation studies by carrying out experiments to test the abilities of non-eukaryotic KsgA/Dim1 family members to complement for yeast Dim1.

Results

Crystallization, refinement and analysis

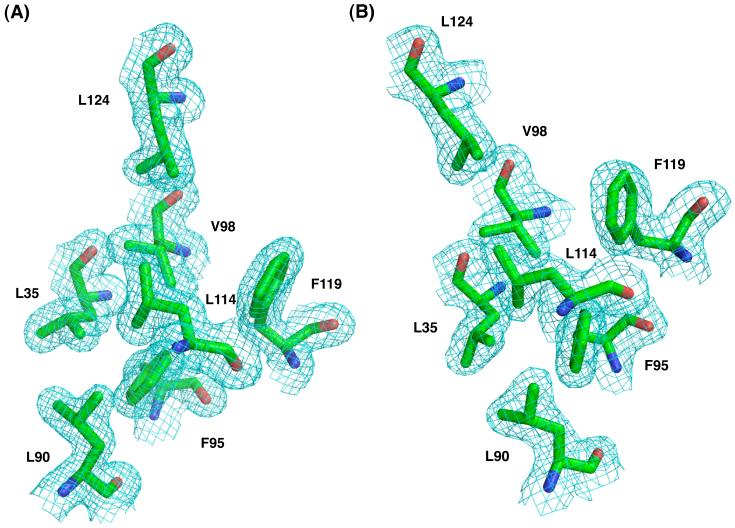

Dim1 from M. jannaschii (MjDim1) was expressed and purified as previously reported.5 Two forms of protein were used in crystallization experiments. Form 1 contained two mutated residues predicted to reduce surface entropy and thus improve crystallization; form 2 retained the wild-type sequence. Table 1 summarizes crystallographic data and refinement statistics. A fundamental difference between the two forms was that form 1 contained a single copy of MjDim1 per asymmetric unit and form 2 contained two copies. Initial phasing information came from using the program Phaser using a composite search model generated from the E. coli KsgA structure and Dim1 structures from H. sapiens and P. falciparum.14 Interestingly, no single KsgA/Dim1 ortholog provided a useful molecular replacement solution on its own, suggesting that none of the other KsgA/Dim1 structures is a close enough structural match to MjDim1. After several rounds of model building and refinement, R and Rfree for form 1 were 17.6 and 22.6 %, respectively. The corresponding values for form 2 were 20.2 and 27.3%. The two pairwise root mean square deviation (RMSD) values between the structures in form 2 with the structure in form 1 are 0.457 Å and 0.526 Å, indicating that the structures from the two crystal forms are nearly identical. Therefore, unless otherwise specified, discussion will center on the structure from crystal form 1, which diffracted x-rays to a greater resolution. Representative regions of the electron density map and molecular fit are shown in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

X-ray data collection and refinement

| Form 1 | Form 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| A. Data Collection | ||

| Space group | P21 | P21 |

| Unit Cell Parameters | ||

| a (Å) | 40.24 | 40.38 |

| b (Å) | 65.91 | 72.27 |

| c (Å) | 61.93 | 95.88 |

| β (deg.) | 108.1 | 91.86 |

| Resolution overall (high-resolution shell) | 33.1-1.75 (1.81-1.75) | 32.8-2.15 (2.23-2.15) |

| Nobs | 29365 (2804) | 28619 (2770) |

| Completeness (%) | 94.4 (91.1) | 94.9 (91.9) |

| Rsymm | 0.038 (0.294) | .091 (.361) |

| I/σ(I) | 29.1 (4.9) | 12.4 (4.7) |

| Multiplicity | 7.06 (6.98) | 6.62 (6.65) |

| Wilson Plot B (Å2) | 38.9 | 37.9 |

| Optical Resolution (Å) | 1.48 | 1.68 |

| B. Refinement | ||

| Resolution range overall (high-resolution shell) | 22.0-1.75 (1.80-1.75) | 32.0-2.15 (2.21-2.15) |

| Reflections work/free | 26413 \ 2926 | 25730 \ 2873 |

| Protein atoms | 2177 | 4307 |

| Water atoms | 333 | 302 |

| Rwork overall (high-resolution shell) | 0.176 (0.215) | .202 (.309) |

| Rfree overall (high-resolution shell) | 0.226 (0.305) | .273 (.357) |

| Roverall | 0.181 | 0.209 |

| <B>(Å2) | 44 | 36.4 |

| Cruickshank’s DPI (Å) | 0.12 | 0.24 |

| Estimated maximal coordinate error | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| RMSD bond lengths (Å) | 0.011 | 0.007 |

| RMSD bond angles (deg.) | 1.13 | 1.12 |

| Ramachandran Plot | ||

| Most favored (%) | 229 (93.5) | 461 (93.3) |

| Additionally allowed (%) | 15 (6.1) | 31 (6.3) |

| Generously allowed (%) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) |

| Forbidden (%) | 0 | 0 |

Fig. 1.

Representative 2Fo-Fc electron density map, contoured to 1.0 σ, of both forms of MjDim1. Shown are the side chains from select residues. (a) Form 1. (b) Form 2.

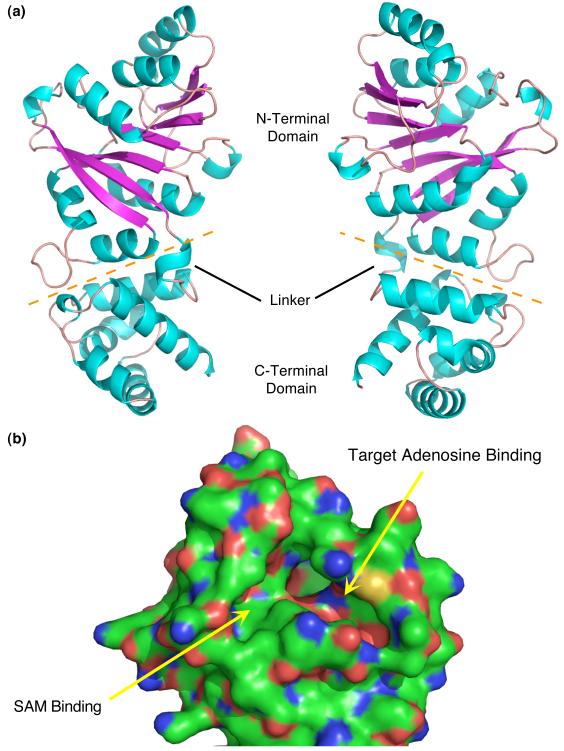

MjDim1 is composed of two sequential domains linked by a short and likely flexible linker (Fig. 2). The catalytic pocket is located in the N-terminal domain and is composed of a modified Rossmann fold, a feature common to SAM dependent methyltransferases. There are two deep, well formed pockets, one which accepts the methyl donor, SAM, and the second which accepts the target adenosines, one at a time, for modification. The C-terminal domain is composed entirely of α-helices and intervening loops. The only regions missing electron density are at the leading and tailing regions of the N-terminal and C-terminal domains.

Fig. 2.

Structure of MjDim1. (a) Two views, rotated 180°, of the structure of MjDim1. α-helices are in cyan and β-strands are in magenta. The orange dashed line separates the two domains. The linker connecting the two domains is labeled, as are the domains. (b) A close up of the N-terminal domain highlighting the ligand binding pockets, as annotated.

Structural comparison with other KsgA/Dim1 family members

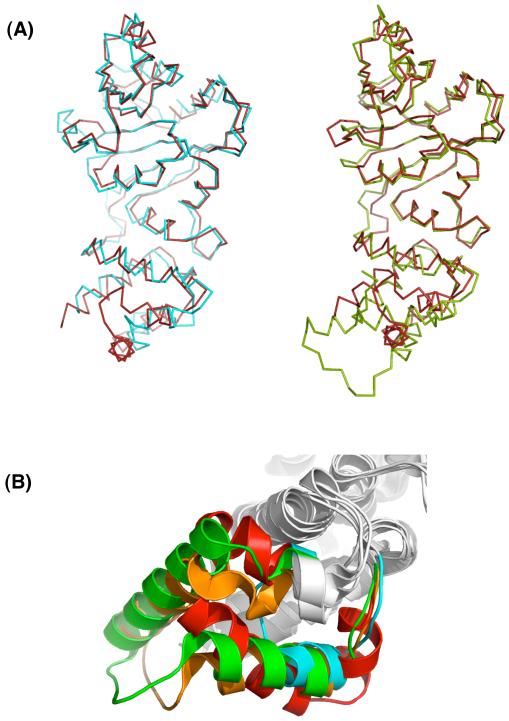

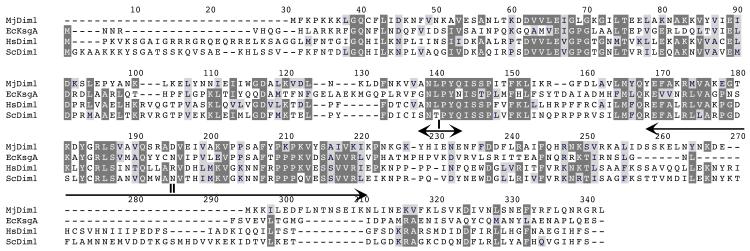

Cursory examination of the structure of MjDim1 reveals that it has numerous similarities with the structures of the other KsgA/Dim1 orthologs that have been solved. When MjDim1 is superposed with other KsgA/Dim1 structures, regions of similarities and differences can be clearly defined (Fig. 3). We made direct structural comparisons among the members of the KsgA/Dim1 family that have had their structures determined by measuring the RMSD of the regions conserved in all four members (Table S1). In all but the MjDim1 case, there are two peptide copies per asymmetric unit that can differ by as much as 1.2 Å in RMSD. Therefore, both copies were independently superposed and the pairings that resulted in the lowest RMSD value are the ones reported (Table 2). The RMSD values range from 1.4 Å for PfDim1 to 1.6 Å for KsgA. The structural variability among the family members even within the most conserved regions might explain why a composite KsgA/Dim1 structure was successful in providing useful molecular replacement information, whereas individual structures were not. (Without the benefit of hindsight we included even more highly variable regions in our original search models). We constructed a sequence alignment based on the sequences and 3-D structures of MjDim1, EcKsgA, and HsDim1, and the sequence of ScDim1 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Overlays of Dim1 and KsgA structures. (a) Whole structure overlays of MjDim1 (red) and KsgA (cyan); and MjDim1 (red) and HsDim1 (green) (b) Up-close view of the overlapped C-terminal domains of KsgA (cyan), HsDim1 (green), PfDim1 (orange), and MjDim1 (red) showing the variable insert region.

Table 2.

Root mean square differences (and percent identity in sequence) among KsgA/Dim1 family members in Ångstroms

Fig. 4.

Structure based sequence alignment based on the structures of MjDim1, EcKsgA, and HsDim1 and the sequence of ScDim1. Residues that are most conserved in all four proteins have a dark background, reduced conservation is connoted with a light grey background. Boxed in red is the site of the E85A mutation used in this work. Motif I indicates the linker region used to swap domains. Motif II connotes the highly variable region in the KsgA/Dim1 family of enzymes.

Very few structural differences were seen within the core of the catalytic site, the region with the highest concentration of conserved residues, which was not surprising given that KsgA/Dim1 family members all catalyze identical methyltransferase reactions and likely orient substrates in identical ways. In all four cases there are well-formed ligand pockets and identical chain trajectories, cementing the conclusion that the family members work in identical ways. Although none of the structures have ordered N-terminal leaders, this region is expected to differ among the family members because the leaders are significantly different in length. Otherwise, small structural differences are sprinkled throughout the N-terminal domain.

A notably different outcome was observed in the C-terminal (non-catalytic) domain, where a highly variable region that can span anywhere from about 20-50 residues in length is embedded within structurally conserved α-helices (Fig. 3). The first and last α-helices of KsgA and the Dim1 proteins are roughly conserved in position and length, but for the most part not in sequence. However, there is a conserved cluster of positive residues common to all of the known structures, which for KsgA was predicted to interact with 16S rRNA.7 The intervening segment is highly variable across deep phylogenetic divisions (Fig. 4). The two eukaryotic Dim1 structures show conservation within the variable region (Fig. 3b), but KsgA and MjDim1 are uniquely represented in the set.

Functional complementation

KsgA/Dim1 enzymes from all three domains are able to methylate E. coli 30S subunits in vivo and in vitro, indicating that all members of this family retain functional conservation that extends to subunit recognition. Catalysis is only one known function for some members of the KsgA/Dim1 family. Most notably, Dim1 in eukaryotic organisms is an essential member of the processome, a multi-factor assembly that doesn’t exist in bacteria. It is not known if archaea utilize a similar processome in ribosome biogenesis. Since Dim1’s involvement in the processome is essential, we used the technique of plasmid shuffling to probe the ability of bacterial KsgA and archaeal Dim1 to complement for Dim1 (ScDim1) function in S. cerevisiae.15

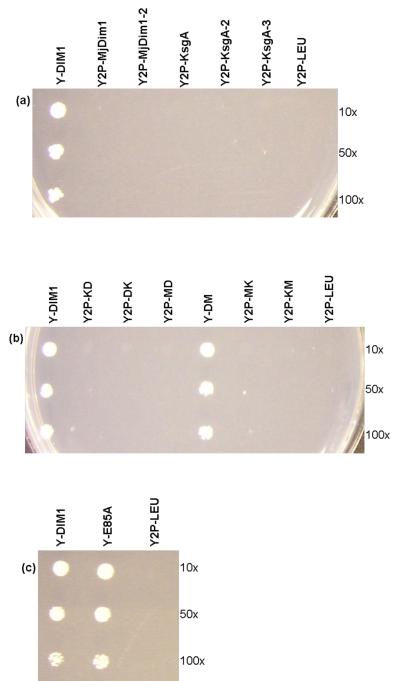

A haploid yeast strain (Y26hα-URA-DIM1) was generated which lacks the chromosomal DIM1 copies but rescued by the plasmid-borne DIM1 (pESC-URA-DIM1). This strain was transformed separately with pESC-LEU vectors containing KsgA (of E. coli) and MjDim1 both with and without an exogenous NLS, in order to ensure that the resultant proteins could be targeted to the nucleus. pESC-LEU-DIM1 and pESC-LEU were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. The transformants were grown in minimal medium with uracil and then plated on 5-FOA, which selects for the loss of the first plasmid, pESC-URA-DIM1. Plates were incubated for 3 days at 30°C and except for the positive control (Y2P-DIM1) none of the constructs of KsgA or MjDim1 were able to rescue the lethal phenotype of the DIM1 knockout (Fig. 5a). In order to ascertain that the exogenous NLS is not interfering with the activity, another construct in which the NLS is fused to the N-terminal end of ScDim1 was tested as a control and found to be innocuous (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Complementation assay on 5-FOA plates at 30°C for 3 days, of (a) different constructs of KsgA and MjDim1, (b) chimeras and (c) dim1-E85A. Y2P-DIM1 serves as a positive control and Y2P-LEU, with no insert in the second plasmid, is the negative control.

The use of KsgA/Dim1 hybrid enzymes

It appears that ScDim1 possesses some feature or features that are not present in either MjDim1 or EcKsgA. Therefore, in an effort to localize the critical regions of ScDim1 function to one domain or the other, we constructed all six chimeras that result from swapping the two domains of ScDim1, EcKsgA, and MjDim1 (Table 3). Such a strategy was thought possible since the N- and C-terminal domains are tethered through a single linker and with reported interdomain mobility for the KsgA enzyme.12 While there is significant sequence conservation among N-terminal residues involved in the interface (E. coli KsgA residues within in the range of 151-168), poor sequence conservation exists for C-terminal interfacial residues (E. coli KsgA residues within the ranges 206-220 and 249-254), suggesting that interactions across the interface are only modestly conserved (see the article by O’Farrell et al.16 for a discussion of KsgA sequence conservation).

Table 3.

Chimera protein construction

| Parent Domains | Chimera protein |

|---|---|

| N terminal - EcKsgA C terminal - ScDim1 |

KD |

| N terminal - ScDim1 C terminal - EcKsgA |

DK |

| N terminal - MjDim1 C terminal - ScDim1 |

MD |

| N terminal - ScDim1 C terminal - MjDim1 |

DM |

| N terminal - MjDim1 C terminal - EcKsgA |

MK |

| N terminal - EcKsgA C terminal - MjDim1 |

KM |

The linker region in ScDim1 has two residues, valine and aspartate which are also found in the linker region of EcKsgA but with a lysine in between them. Sequence alignment shows that the corresponding position in MjDim1 has isoleucine and glutamate (indicated in Fig. 4). These residues were selected as a center for domain swapping. To construct chimeric proteins, the N and C terminal domains of DIM1, KsgA-NLS and MjDim1-NLS were amplified separately and ligated to form the six possible combinations. Chimeras were named to indicate the origin of each domain (Table 3). All of the six chimeric genes were cloned into pET15b and the proteins were overexpressed in E. coli and shown to be soluble to some degree, with the possible exception of chimera DK, which was only marginally soluble (data not shown). The chimeras were also assessed in an in vivo assay in bacteria, and shown to complement for KsgA function, again to varying degrees (Table 4). Chimeric proteins DM and DK showed the poorest overall solubility and in vivo activity.

Table 4.

In vivo activity assay in E. coli

| Plasmid | MIC (μg/mL ksg)† |

|---|---|

| pET15b | >3000 |

| pET15b-KsgA | 400 |

| pET15b-ScDim1 | 1200 |

| pET15b-MjDim1 | 400 |

| pET15b-KD | 1200 |

| pET15b-DK | 2000* |

| pET15b-MD | 400 |

| pET15b-DM | 2000* |

| pET15b-MK | 400 |

| pET15b-KM | 800 |

Concentrations of kasugamycin (ksg) in μg/mL used in the assay are 0, 200, 400, 600, 800, 1000, 1200, 1500, 2000, 2500, 3000.

Very small colonies were observed

The chimeric genes were then subcloned into pESC-LEU and transformed into Y26hα-URA-DIM1; the transformants were plated on 5-FOA. Interestingly, only Y2P-DM survived, showing that only the N-terminal ScDim1/C-terminal MjDim1 chimera was able to complement for the processing function of ScDim1 (Fig. 5b). As with Y2P-DIM1, Y2P-KsgA, and Y2P-MjDim1, all six chimeras demonstrated expression and significant nuclear presence as detected by fluorescence microscopy (see Supplementary material, Fig. S1).

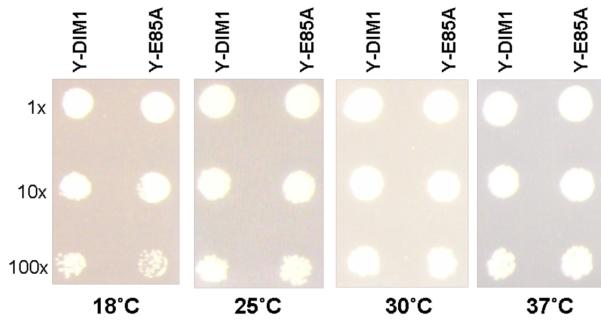

Importance of the methyl groups to S. cerevisiae growth

Finally we sought to construct a minimally altered protein that no longer demonstrated methyltransferase activity. For KsgA we previously did this by making the E66A point mutation to disrupt SAM binding capabilities.8 The analogous mutation in ScDim1 is the E85A change. The altered protein was able to complement for Dim1 (Fig. 5c) but yielded a protein with no catalytic activity as determined by primer extension of 18S rRNA (Fig. S2 in Supplementary material). The expected primer extension stops at 1779 and 1780 were missing in rRNA extracted from the strain expressing catalytically inactive ScDim1. Lafontaine et al. previously reported that the methyl groups themselves were not important to overall function in vivo at normal growth temperatures.10 The only observed phenotype reported was slower growth at 37°C. In that work, the inactive dim1 gene contained six mutations with no obvious rationale as to why the resulting protein was catalytically inactive. With our single mutant, we observed no change in growth rate of yeast at 18, 25, 30, and 37 °C (Fig. 6), suggesting that the mutations investigated by Lafontaine et al. had at least one additional consequence to Dim1 function outside its methyltansferase function that affected cell growth.

Fig. 6.

Growth phenotypes of Y-DIM1 (with wild type Dim1) and Y-E85A (with catalytically inactive dim1-E85A protein). Both strains showed identical growth rates.

Conclusions

The KsgA/Dim1 family has the remarkable status of being one of only about fifty genes conserved in all organisms and is thought to have arisen from the last common ancestor, perhaps the only ribosome biogenesis factor with that common origin. We show here that KsgA/Dim1 orthologs from bacteria, eukarya, and archaea all share considerable three dimensional structural similarities despite having overall fairly low primary structure conservation. Functional and structural divergence has clearly occurred since the splits of the three phylogenetic domains. While dimethylation of rRNA adenosines remains a core function, secondary roles in ribosomal biogenesis do not appear to be functionally conserved in bacteria and eukarya; it is not known whether or not there is a secondary role for Dim1 in archaeal ribosome biogenesis. As demonstrated here, complementation appears to exist in only a single direction. Orthologs from archaea and eukarya can complement for KsgA function in E. coli, yet, complementation by bacterial and archaeal orthologs in S. cerevisae does not appear to be possible.

Presumably the reason that E. coli KsgA and M. jannaschii Dim1 cannot complement for eukaryotic Dim1 in S. cerevisiae is because of Dim1’s well documented role in the ribosomal small subunit processome, an assembly that doesn’t exist in bacteria. Based on sequence alignments alone, a reasonable prediction identifies an insert (relative to E. coli KsgA) present in the C-terminal domain of all known eukaryotic Dim1 proteins that may be involved in its processome function.16 The archaeal Dim1 proteins also have a sequence insert in this region relative to bacterial KsgA, but it is much shorter than that in eukaryotes. Structurally, both ScDim1 amd MjDim1 have inserts relative to EcKsgA, in approximately the same position. However, the structural paths taken by the inserts of MjDim1 and ScDim1 are significantly different, with only a small portion overlapped when the two structures are overlaid (Fig. 3). The fact that the DM chimera effectively complemented for ScDim1 function suggests that any role this insert plays in eukaryotic Dim1’s processome function isn’t essential; however, we cannot rule out the possibility that this overlapped portion is critical to eukaryotic Dim1 activity.

What can be concluded about other domain requirements for Dim1 function? First, it appears that the N-terminal domain of ScDim1 cannot be substituted by analogous domains from EcKsgA and MjDim1, as neither KD nor MD were able to complement for ScDim1. Second, the C-terminal domain is a weaker determinant for Dim1 function in vivo, by virtue of the fact that chimera DM was able to complement for ScDim1, and it did so robustly. On the other hand, the chimera DK failed to complement. (A strict adherance to the conclusion that DK failed because it lacked an essential identity element is confounded by the fact that DK was poorly soluble when overexpressed in E. coli.) Overall we favor an interpretation that structural elements necessary for ScDim1’s role in processome function are distributed between both domains and their identification may prove challenging. Experiments are currently underway to better define the structure/function relationships of eukaryotic Dim1.

Materials and methods

Crystallographic analysis of MjDim1

Protein expression and purification were carried out as previously described,5 except for the protein used to grow form 1 crystals of MjDim1. Form 1 crystals were grown from protein altered with mutations (K137A, E138A) thought to improve the chances and quality of crystallization by reducing surface entropy effects17 (http://www.doembi.ucla.edu/Services/SER). Mutations were introduced using the Quick Change protocol (Stratagene) and the primers 5′- GCC AAG AGA ATG GTA GCT GCC GCG GGA ACA AAA GAT TAT GGA AGG -3′ and 5′- CCT TCC ATA ATC TTT TGT TCC CGC GGC AGC TAC CAT TCT CTT GGC -3′. Expressed protein of both forms was dialyzed into 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 50 mM NaCl and 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and was concentrated to a value of 25-30 mg/ml prior to crystallization. Protein purity was assessed by SDS-PAGE. Crystals of the form 1 type were grown by the hanging drop method (protein: reservoir solution ratio 1:1) at 17°C using PEG 8000 (14-16%) in the presence of 25 mM MES (pH 6.2), 50 mM (NH4)2SO4 and 7 mM MgCl2 as a precipitant. Crystals typically reached maximal size over 1-2 weeks. Crystals of form 2 were grown from protein containing wild type sequence, expressed and purified in the same way. Hanging drops composed of 2μl protein, 1μl NaH2PO4 (50mM) and 2.5μl PEG 3350 (18%) were equilibrated against 900 μl of a solution containing PEG 3350 (24%) at 17°C. Again crystals reached maturity over the span of 1-2 weeks. For both forms crystals were cryoprotected using 35% PEG 8000 (form 1) and 36% PEG 3350 (form 2) prior to flash cooling.

Diffraction sets were collected as 0.5° oscillation frames on an R-AXIS IV image plate detector using CuKa radiation from a rotating anode generator operating at 50 kV and 100 mA with Rigaku Varimax optics. Data integration, merging, and scaling were performed with D*Trek suite of programs. Form 1 crystals diffracted x-rays to 1.75 Å and were of the P 21 space group, while form 2 crystals diffracted x-rays to 2.15 Å and were also of the P 21 space group. Initial phases for Form 1 were generated using the program Phaser from the Phenix suite of programs14 and required the use of a composite model generated from structures of KsgA12 (1QYR), P. falciparum Dim113 (2H1R), and human Dim1 (1ZQ9; unpublished structure from the Structural Genomics Consortium). The initial model was improved via the autobuild function in Phenix. The resulting model was refined by iterative cycles of manual rebuilding using the program Coot18 with 2mFo-Fc and mFo-dFc maps followed by computational refinement with Phenix and REFMAC.19 Model quality was monitored via the use of Procheck and the valdiation functions in COOT. Structure solution and refinement for form 2 were carried out using protocols identical to those employed for form 1. Crystallographic data and refinement statistics for both forms are summarized in Table 1.

Plasmids for the complementation assays

DIM1 of S. cerevisiae was amplified from pET15b-DIM1 as an XhoI-NheI fragment and subcloned into the pESC-URA vector (Stratagene) to give pESC-URA-DIM1, which results in Dim1 with an N-terminal myc epitope. This clone and all subsequent clones were confirmed by sequencing at the Nucleic Acids Research Facilities, Virginia Commonwealth University. KsgA of E. coli was amplified from pET15b-KsgA as a NotI-SpeI fragment with an exogenous NLS (nuclear localization signal - PPKKKRKV) and subcloned into the pESC-LEU vector (Stratagene) to give pESC-LEU-KsgA, which results in KsgA with an N-terminal NLS and a C-terminal FLAG epitope. Similarly, MjDim1 was amplified from pET15b-MjDim1 as a NotI-SpeI fragment with the exogenous NLS and subcloned into pESC-LEU to give pESC-LEU-MjDim1, which results in MjDim1 with an N-terminal NLS and a C-terminal FLAG epitope. KsgA was also amplified as a BglII-PacI fragment (without exogenous NLS) and subcloned into pESC-LEU to give pESC-LEU-KsgA-2, which results in KsgA with an N-terminal FLAG epitope. DIM1, KsgA, MjDim1 were also amplified as NotI-SpeI fragments (without exogenous NLS) and subcloned into pESC-LEU to give pESC-LEU-DIM1, pESC-LEU-KsgA-3, and pESC-LEU-MjDim1-2 respectively, which results in the respective protein with a C-terminal FLAG epitope. As a control DIM1 was amplified from pET15b-DIM1 as a NotI-SpeI fragment with the exogenous NLS and subcloned into pESC-LEU to give pESC-LEU-DIM1-2, which results in Dim1 with an N-terminal NLS and a C-terminal FLAG epitope.

Chimera plasmids

The N-terminal and C-terminal domains of DIM1, KsgA, MjDim1 were amplified separately as NdeI-SalI and SalI-XhoI fragments. The amplicons were then digested with SalI and ligated as following. The N-terminal domain of KsgA was ligated with the C-terminal domains of DIM1 and MjDim1 to generate KD and KM chimeras respectively. The N-terminal domain of DIM1 was ligated with the C-terminal domains of KsgA and MjDim1 to generate DK and DM chimeras respectively. The N-terminal domain of MjDim1 was ligated with the C-terminal domains of DIM1 and KsgA to generate MD and MK chimeras respectively. All six chimeras were inserted into pET15b as NdeI-XhoI fragments. DK and DM were again amplified as NotI-SpeI fragments and subcloned into pESC-LEU to give pESC-LEU-DK and pESC-LEU-DM, which results in protein with C-terminal FLAG epitope. KD, KM, MD and MK were amplified as NotI-SpeI fragments (with exogenous NLS) and subcloned into pESC-LEU to give pESC-LEU-KD, pESC-LEU-KM, pESC-LEU-MD, pESC-LEU-MK, which results in protein with N-terminal NLS and C-terminal FLAG epitopes. (See Supplementary material for primer information)

In vivo assay in bacteria

E. coli cells resistant to kasugamycin were transformed with the pET15b constructs and selected on LB plates containing ampicillin. Transformed colonies were inoculated into liquid media and grown overnight. These cultures were diluted 1:25 in fresh LB containing 50 μg/mL ampicillin and grown to an OD600 of 0.7-0.8. The cultures were again diluted 1:100 in fresh LB and 3 μL of the dilution was plated onto LB/ ampicillin containing increasing amounts of kasugamycin, from 0 to 3000 μg/mL. Plates were incubated at 37°C overnight and visually inspected for colony formation.

Mutagenesis

The E85A mutation in pESC-LEU-DIM1 was generated using the QuikChange XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) and primers 5′-CGT AGT GGC AGT AGC AAT GGA TCC CAG AAT GG-3′ and 5′-CCA TTC TGG GAT CCA TTG CTA CTG CCA CTA CG-3′ to give pESC-LEU-dim1-E85A.

Yeast strains

Standard S. cerevisiae growth and handling techniques were employed. Media were standard yeast extract/peptone supplemented with either glucose (YPD) or 2% galactose (YPGal), or minimal medium (0.67% YNB, appropriate amino acids, 2% galactose), all containing 200 mg/L Geneticin (G418). Transformation was carried out using the LiOAc/PEG method.20

The yeast deletion clone #21026 generated by the Saccharomyces Genome Deletion Project (http://www-sequence.stanford.edu/group/yeast_deletion_project/deletions3.html) was obtained from Invitrogen (catalog no. 95400). Y-21026 is a diploid strain, derived from BY4743, that is heterozygous for DIM1 deletion (one chromosomal DIM1 copy is replaced with the KanMX4 module). BY4743 is auxotrophic for histidine, leucine and uracil and hence the genotype of Y-21026 is MAT a/α his3Δ1/his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 /leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0/LYS2 MET15/met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 /ura3Δ0 DIM1/dim1Δ0::KanMX4. This strain was transformed with pESC-URA-DIM1 and induced to sporulate. Tetrads were dissected on synthetic medium lacking uracil to maintain selection for the plasmid. Spore colonies that were Ura+ and Geneticin-resistant were tested for mating type. From these spores, a strain of the genotype MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 dim1Δ0::KanMX4 (pESC-URA-DIM1), labeled as Y26hα-URA-DIM1, was selected for further transformations.

Complementation assay

Y26hα-URA-DIM1 was transformed with a second plasmid, pESC-LEU-DIM1, pESC-LEU-DIM1-2, pESC-LEU-KsgA, pESC-LEU-KsgA-2, pESC-LEU-KsgA-3, pESC-LEU-MjDim1, pESC-LEU-MjDim1-2, or pESC-LEU(no insert) to give Y2P-DIM1, Y2P-DIM1-2, Y2P-KsgA, Y2P-KsgA-2, Y2P-KsgA-3, Y2P-MjDim1, Y2P-MjDim1-2 and Y2P-LEU respectively.

Y26hα-URA-DIM1 was also transformed with the chimera plasmids, pESC-LEU-KD, pESC-LEU-DK, pESC-LEU-MD, pESC-LEU-DM, pESC-LEU-MK, pESC-LEU-KM and the plasmid with mutant DIM1 (pESC-LEU-dim1-E85A) to give Y2P-KD, Y2P-DK, Y2P-MD, Y2P-DM, Y2P-MK, Y2P-KM and Y2P-E85A respectively.

Fluoro-orotate resistant clones were selected on minimal medium (YNB, histidine, uracil, galactose) containing 1 g/L 5-Fluoro-orotic acid (5-FOA).15 Plates were incubated for 3 days at 30°C. Y2P-DIM1, Y2P-DIM1-2, Y2P-DM, Y2P-E85A survived on 5-FOA, losing the first plasmid, pESC-URA-DIM1, and hence these 5-FOA resistant clones with only the second plasmid were labeled Y-DIM1, Y-DIM1-2, Y-DM, and Y-E85A respectively (Table S3 in Supplementary material).

The plasmids in the yeast strains were confirmed by PCR followed by sequencing.

Cell growth comparison between Y-DIM1 and Y-E85A

Colonies of Y-DIM1 and Y-E85A were inoculated into 2ml of minimal medium and grown to an OD600 of 1.0. Dilutions (1x to 100x) of both strains were spotted on minimal media plates and incubated for 3 days at 25, 30, and 37°C and for 4 days at 18°C. For confirmation, the rRNA was isolated from both wild type and non-dimethylated 40S subunits and primer extension was carried out on both using the primer 5′-TAA TGA TCC TTC CGC A-3′, which is complementary to the very end of 18S rRNA10,21 (Fig. S2 in Supplementary material).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Jean Vandenhaute for kindly providing us with the pET15b-DIM1 construct. Microscopy was performed at the VCU Dept. of Neurobiology & Anatomy Microscopy Facility, supported, in part, with funding from NIH-NINDS Center core grant (5P30NS047463). This work was supported by the NIH Grant (GM066900) awarded to J.P. Rife. Support for the structural biology resources used in this study provided from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (CA 16059-28) to the Massey Cancer Center is gratefully acknowledged.

Abbreviations

- Sc

Saccharomyces cerevisiae

- Hs

Homo sapiens

- Mj

Methanocaldococcus jannaschii

- Ec

Escherichia coli

- Pf

Plasmodium falciparum

- 5-FOA

5-fluoroorotic acid

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Protein Data Bank accession codes

Coordinates and structure factors have been submitted to the Protein Data Bank and have been assigned the codes PDB ID: 3FYC and PDB ID: 3FYD.

References

- 1.Poldermans B, Roza L, Van Knippenberg PH. Studies on the function of two adjacent N6,N6-dimethyladenosines near the 3′ end of 16 S ribosomal RNA of Escherichia coli. III. Purification and properties of the methylating enzyme and methylase-30 S interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 1979;254:9094–9100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Buul CP, van Knippenberg PH. Nucleotide sequence of the ksgA gene of Escherichia coli: comparison of methyltransferases effecting dimethylation of adenosine in ribosomal RNA. Gene. 1985;38:65–72. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90204-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Buul CP, Damm JB, Van Knippenberg PH. Kasugamycin resistant mutants of Bacillus stearothermophilus lacking the enzyme for the methylation of two adjacent adenosines in 16S ribosomal RNA. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1983;189:475–478. doi: 10.1007/BF00325912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lontaine D, Delcour J, Glasser AL, Desgres J, Vandenhaute J. The DIM1 gene responsible for the conserved m6(2)Am6(2)A dimethylation in the 3′-terminal loop of 18 S rRNA is essential in yeast. J. Mol. Biol. 1994;241:492–497. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Farrell HC, Pulicherla N, Desai PM, Rife JP. Recognition of a complex substrate by the KsgA/Dim1 family of enzymes has been conserved throughout evolution. RNA. 2006;12:725–733. doi: 10.1261/rna.2310406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris JK, Kelley ST, Spiegelman GB, Pace NR. The genetic core of the universal ancestor. Genome Res. 2003;13:407–412. doi: 10.1101/gr.652803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu Z, O’Farrell HC, Rife JP, Culver GM. A conserved rRNA methyltransferase regulates ribosome biogenesis. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:534–536. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Connolly K, Rife JP, Culver G. Mechanistic insight into the ribosome biogenesis functions of the ancient protein KsgA. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;70:1062–1075. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06485.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schafer T, Strauss D, Petfalski E, Tollervey D, Hurt E. The path from nucleolar 90S to cytoplasmic 40S pre-ribosomes. EMBO J. 2003;22:1370–1380. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lafontaine DL, Preiss T, Tollervey D. Yeast 18S rRNA dimethylase Dim1p: a quality control mechanism in ribosome synthesis? Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:2360–2370. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.4.2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seidel-Rogol BL, McCulloch V, Shadel GS. Human mitochondrial transcription factor B1 methylates ribosomal RNA at a conserved stem-loop. Nat. Genet. 2003;33:23–24. doi: 10.1038/ng1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Farrell HC, Scarsdale JN, Rife JP. Crystal structure of KsgA, a universally conserved rRNA adenine dimethyltransferase in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;339:337–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vedadi M, Lew J, Artz J, Amani M, Zhao Y, Dong A, et al. Genome-scale protein expression and structural biology of Plasmodium falciparum and related Apicomplexan organisms. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2007;151:100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zwart PH, Afonine PV, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Hung LW, Ioerger TR, McCoy AJ, et al. Automated structure solution with the PHENIX suite. Methods Mol. Biol. 2008;426:419–435. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-058-8_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boeke JD, Trueheart J, Natsoulis G, Fink GR. 5-Fluoroorotic acid as a selective agent in yeast molecular genetics. Methods Enzymol. 1987;154:164–175. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)54076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Farrell HC, Xu Z, Culver GM, Rife JP. Sequence and structural evolution of the KsgA/Dim1 methyltransferase family. BMC Res. Notes. 2008;1:108. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-1-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldschmidt L, Cooper DR, Derewenda ZS, Eisenberg D. Toward rational protein crystallization: A Web server for the design of crystallizable protein variants. Protein Sci. 2007;16:1569–1576. doi: 10.1110/ps.072914007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ito H, Fukuda Y, Murata K, Kimura A. Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J. Bacteriol. 1983;153:163–168. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.1.163-168.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lafontaine D, Vandenhaute J, Tollervey D. The 18S rRNA dimethylase Dim1p is required for pre-ribosomal RNA processing in yeast. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2470–2481. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.20.2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maiti R, Van Domselaar GH, Zhang H, Wishart DS. SuperPose: a simple server for sophisticated structural superposition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W590–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.