Abstract

Background

In February 2002, the VA increased copayments from $2 to $7 per 30-day drug supply of each medication for many veterans. We examined the impact of the copayment increase on lipid lowering medication adherence.

Methods and Results

Quasi-experimental study using electronic records of 5,604 veterans receiving care at the Philadelphia VA Medical Center from November, 1999 to April, 2004. The “All Copayment” group included veterans subject to copayments for all drugs with no annual cap. Veterans subject to copayments for drugs only if indicated for a non-service connected condition with an annual cap of $840 for out-of-pocket costs comprised the “Some Copayment” group. Veterans who remained copayment exempt formed a natural control group (“No copayment” group). Patients were identified as “adherent” if the proportion of days covered (PDC) with lipid-lowering medications was >= 80%. Patients were identified as having a “continuous gap” if they had at least one continuous episode with no lipid lowering medications for >= 90 days. A difference-indifference approach comparing changes in lipid lowering medication adherence during the 24 months pre- and post- copayment increase among veterans subject to the copayment change versus those who were not.

Adherence declined in all three groups after the copayment increase. However, the percent of patients who were adherent (PDC>=80%) declined significantly more in the all copayment (-19.2%) and some copayment (-19.3%) groups relative to the exempt group (-11.9%). The incidence of a continuous gap increased significantly at twice the rate in both copayment groups (+24.6% all copayment group and 24.1% some copayment group) than the exempt group (+11.7%). Compared to the exempt group, the odds of having a continuous gap in the post- relative to the pre-period were significantly higher in both the all copayment group (OR 3.04 95% CI 2.29-4.03) and the some copayment group (OR 1.85 95% CI 1.43-2.40). Similar results were seen in subgroups of high CHD risk patients, high medication users, and elderly veterans.

Conclusion

The copayment increase adversely impacted lipid lowering medication adherence among veterans including those at high CHD risk.

Background

With the rate of spending growth for prescription medications far outpacing other areas of medical care, health plans and employers have increased patient cost sharing for prescription drugs in an attempt to control escalating costs in recent years.1 As in the private sector, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has also faced rapid increases in pharmaceutical spending. In the late 1990s, VA outpatient prescription expenditures were increasing at a 19% annual rate and totaled almost $3 billion in fiscal year 2001.2 To combat these rising expenditures, the VA also increased patient cost-sharing through the Veterans Millennium Health Care Act of 1999 (Public Law 106-117), which increased co-payments for outpatient medications from $2 to $7 per 30 day or less supply of each medication starting February 2002.

Numerous studies in the private sector have confirmed that such policies generally result in significant savings in medication costs by reducing utilization.3, 4 Some studies, however, have also found reductions in the use of essential medications and disruptions in treatment for chronically ill patients. 3, 4 Little is known about how changes in copayment policy affect essential medication use among VA patients, a low socioeconomic status group with a high rate of comorbidites. Only two published studies to date have assessed the effect of the copayment increase under Public Law 106-117: one study examined changes in the number of 30-day medication supplies for all chronic medications and for broad categories of chronic medications defined as low versus high cost chronic medications and over-the-counter versus prescription-only chronic medications5 ; the second study focused only on patients with schizophrenia. 6

Evaluation of the effect of this policy change in veterans with other chronic conditions and on use of specific essential medication classes is needed to inform ongoing policy debates, as further increases in VA copayments have been part of recently proposed Presidential budgets. 7, 8

Statins (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors), the most commonly used lipid lowering agents, have been shown to significantly reduce the risk of future coronary events and cardiovascular mortality in patients at high coronary heart disease (CHD) risk. 9 Yet studies have shown that treatment and adherence to such lipid lowering drugs is suboptimal among patients in all age groups. 10-12 Given that the prevalence and burden of heart disease in the VA population have been found to be higher than the non-VA population 13 and efforts have been made to improve adherence with anti-cholesterol medications in VA patients14, identifying whether increases in copayments may worsen adherence to these essential medications in this population is critical. This study examines the impact of the VA copayment increase from $2 to $7 on adherence to lipid lowering medications in veterans using prescription refill data.

Methods

Data Source and Study Sample

The study used administrative data and electronic medical record information entered, processed, and stored in the Veterans Health Information Systems Technology and Architecture (VistA) database, which is the automated environment that supports day-to-day operations at local VA health care facilities. This system provides data on patient demographics, copay-exempt status, medical diagnoses, laboratory results, and prescription orders written and filled within the VA system. Our study used the Philadelphia Veterans Affairs Medical Center's (PVAMC) VistA database. The PVAMC is a VA tertiary referral center for the eastern half of the VA Stars & Stripes Healthcare Network, VISN 4, and provides health care for all veterans living in Philadelphia and surrounding seven counties in Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Delaware, a large number of whom are African-American and the majority are men. The study sample frame consisted of patients receiving care at the Philadelphia VAMC who filled at least one lipid lowering medication in the 24 months prior to the copayment increase because patients put on lipid lowering medication are generally intended to stay on it indefinitely. However, to ensure that patients had not already discontinued lipid lowering medication use prior to the copayment policy change, we excluded patients without any evidence of use of these medications in the 3 month period prior to February 1, 2002. Other exclusion criteria included: died during study period, history of dementia or cancer, missing information on copay exemption status, and changes in copay exemption status during study period.

Study Design

A quasi-experimental design was used to compare changes in lipid lowering medication utilization over time for veterans who experienced increases in prescription copayments versus veterans who did not. This pre-post intervention study with a contemporaneous control estimates the impact of the VA copayment increase by comparing the magnitude of the difference in outcomes before and after the increase for veterans subject to the copayments with the magnitude of the difference in outcomes before and after the increase for veterans not subject to copayments.

We determined whether veterans were subject to the prescription copayment depending on their VA Priority category (1 through 8 with 1 being the highest priority). Priority groups were established to help the VA manage access in relation to its available resources and ensure that resources are allocated to veterans with the highest priority for enrollment 2. Veterans with Priority 1 have a service-connected disability rated 50% or more disabling and are exempt from all prescription drug copayments. These “Copay exempt” veterans formed a natural control group given that they did not face copayments in the pre- or post-policy period. Next, we defined two intervention groups who were subject to copayment increases since February 2002. The “Some Copay Group” included veterans in Priority groups 2 through 6 who have service-connected disabilities rated <50% disabling, lower incomes, or other recognized statuses that confer higher priority than those without (e.g. veterans awarded the Purple Heart, former prisoners of war). They are subject to copayments for drugs only if indicated for a non-service-connected (NSC) condition. Since “service-connected” disability refers to a disability that was incurred or aggravated in the line of duty in the active military, naval, or air service (e.g., amputations, burns, post traumatic stress disorder, and traumatic brain injuries), hyperlipidemia is unlikely to be a service-connected disability and hence most veterans in this group were subject to copayments for their lipid lowering medications. Nevertheless, an annual maximum of $840 (increased to $960 in 2006) for out-of-pocket medication costs has been established for these veterans (i.e. no copays for additional fills after 120 prescription months per year). The “All Copay Group” included veterans in Priority Groups 7 or 8 who have incomes and/or net worth above the VA means test threshold and are required to pay copayments for all prescription drugs. An annual medication copayment cap has not been established for veterans enrolled in priority groups 7 or 8.

For each group, the two comparison time periods were a 24-month pre-period (11/1/99-10/31/01) before the copayment increase and a 24-month post-period (5/1/02-4/30/04) after the copayment increase. The 3 month period pre- and post- the copayment increase date was treated as a “washout period” to account for potential stock piling of medications and to allow depletion of existing stores of medications purchased in the pre-period.

Outcome variables

Lipid lowering medication use was measured from the VistA Prescription File which contains records of all outpatient medications dispensed including those processed by the VA mail-order pharmacy. Medication use outcomes were calculated separately for the 24 month pre- and 24 month post-period. The pre-period observation window for new users (identified as those without any lipid lowering medication fill in the 12 months prior to the pre-period) was adjusted to initiate from the date of the first prescription fill if later than 11/01/1999.

Our first outcome was measured as the proportion of days covered (PDC) in each period with lipid lowering medications.15 The PDC was calculated as the number of days with lipid-lowering drug supply on hand divided by the number of days in the specified time period. Information from the VistA prescription file such as the prescription fill date and the days supply was used to designate each day in the period as covered or not. Filled prescriptions were evaluated using a set of rules to avoid double-counting covered days. The portion of the days supply from prescriptions filled before the start date of the time period that would run into the follow-up period was used to assign covered days. When a prescription was issued before the previous prescription should have run out, utilization of the new prescription was assumed to begin the day after the end of the old prescription, and days supply for the new prescription was appended to the end of the previous fill. Any surplus days supply remaining on the last day of the post-period was truncated. Thus, the PDC could only have a value between 0 and 1 and was multiplied by 100 to yield a percentage. On the basis of their PDC measure, patients were classified as adherent in each period if their PDC was >=80%.11, 16 Although the PDC indicates the extent of availability of medication, it does not provide information on whether any gaps in use were continuous or were dispersed over the entire period; each of these scenarios has different clinical implications. Hence, a second set of measures for continuous gaps were used to indicate whether the patient had at least one continuous episode with no lipid lowering medication for a minimum of 90 days in the study periods. Sensitivity analyses were performed with a minimum of 30, 60, and 120-day continuous gap periods.

Independent variables

The independent variables included two dummy variables indicating whether the veteran was in one of the groups that paid copayments (i.e. “Some Copay Group” or “All Copay Group) versus being in the copayment exempt group, a dummy variable indicating whether the observation occurred in the post-period (“Post”), and interaction terms of each copayment group and the post-period variable. The interaction terms were the key independent variables of interest providing an estimate of the policy effect. Other covariates included baseline patient demographics such as age and gender. Since patient-level income was not complete and reliable in the VistA, we used the patient's residence area level median household income information derived from (5-digit) zip-code matched census data as a proxy measure. We also included covariates capturing a history of medical conditions and/or risk factors that could affect the likelihood of using lipid lowering medications such as coronary artery disease, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, and hypertension (see Appendix for ICD-9-CM codes). In addition, the total number of distinct medication classes (except lipid lowering agents) filled per year by the veteran in the pre-period was included as a measure of the complexity of medication regimen and also since the out-of-pocket burden for medication expenses due to the copayment increase would be higher among those using several drugs. Finally, an indicator for a new user of lipid lowering medications was also included as a control variable.

Analysis

A difference-in-difference analytic approach was used. Descriptive results compared the before-after difference in outcomes in each of the two groups subject to copayment increases relative to the copayment exempt group. In multivariate analysis, the impact of the copayment increase was assessed using the copayment status (“All Copay Group”, “Some Copay Group”) by time (“POST”) interaction term for each copayment group. Generalized estimating equations for binary data with logit link function were used to estimate the adherent (i.e. PDC >=80%) and the continuous gap outcomes. Standard errors accounted for the clustering due to repeated observations for each patient. We also examined our outcomes within vulnerable patient subgroups such as those at high risk for CHD (i.e. history of coronary artery disease, atherosclerosis, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, or cerebrovascular disease), elderly veterans (age>=65), and veterans with a high medication burden (i.e. number of distinct medication classes >=5 in pre-period).

While the primary analyses excluded data from the 3 month pre- and post-policy period (“washout” period), in sensitivity analysis we included this period in our analyses. Sensitivity analysis was also conducted by reducing the observation window from 24 months pre- and 24 months post-policy change to 12 months pre- and post-policy. Furthermore, this analysis of 12 months of data pre- and post-policy was conducted with and without the “washout” period. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.1.3 (Cary, North Carolina).

Results

A total of 5,604 patients met the inclusion criteria for the study. About 96% of these patients used statins as the only lipid lowering agent; 0.3 percent of the patients used only a non-statin lipid lowering agent while the remainder had prescriptions for both during the study period. As seen in Table 1, about 9% of the sample was copay exempt (n=495), almost half belonged to the some copayment group (n=2,793) and the remainder in the all copayment group (n=2,316). The mean age of the patients in each group was 70 years or more, with patients in the all and some copayment groups being significantly older than patients in the copayment exempt group. The median zip-code level household income was lowest for the some copayment group followed by the copayment exempt group. As expected per the VA enrollment criteria for the priority groups included in the all copayment group, income was the highest in this group. With the exception of diabetes mellitus and atherosclerosis, the prevalence of other cardiovascular risk factors in the some copayment group was similar to that in the copayment exempt group. On the other hand, the all copayment group had significantly lower prevalence of all cardiovascular risk factors. The number of different medications prescribed per month was significantly higher in the copayment exempt group than in the all and some copayment groups.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics by Copayment Status

| Copay exempt | Some copay group | All copay group | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total N | 495 | 2,793 | 2,316 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 70.1 (11.3) | 73.4 (9.8)* | 76.5 (6.6)* |

| Male | 98.2% | 98.4% | 99.0%* |

| Median household income (in 1000's) | 44.3 | 40.8* | 52.6* |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |||

| Coronary artery disease | 66.9% | 63.9% | 59.5%* |

| Atherosclerosis | 29.1% | 16.8%* | 4.1%* |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 9.1% | 6.3%* | 0.9%* |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 9.9% | 8.8% | 3.1%* |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 13.9% | 13.1% | 5.1%* |

| Hypertension | 81.0% | 81.1% | 69.8%* |

| Median number of distinct medication classes | 8.5 | 6.0* | 3.0* |

Significantly different from copay exempt group at p<0.05

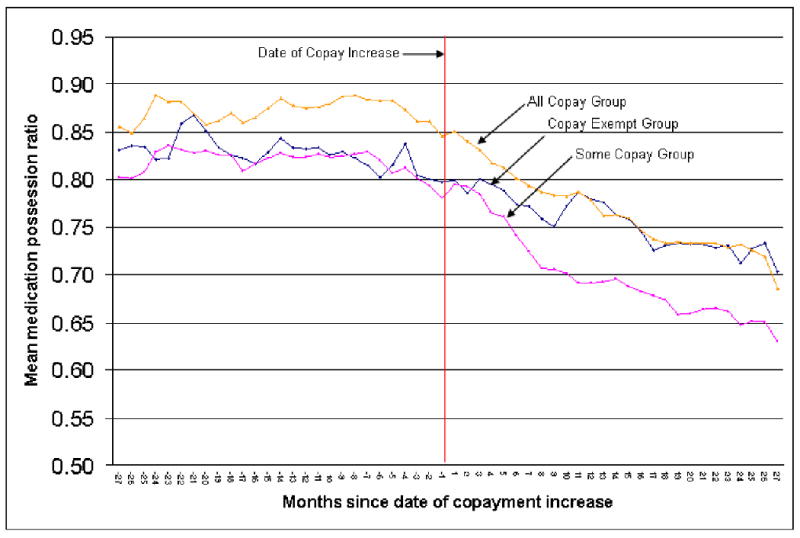

Figure 1 displays plots of the mean PDC in each month in the 24-month periods before and after the copayment increase for the three groups. Adherence levels were high and relatively stable in the majority of the pre-period across all groups, with the highest PDC observed within the all copayment group (mean PDC=0.89). The PDC in the pre-period for both the some copayment and the copayment exempt groups were similar and slightly lower (mean PDC=0.83 in both groups). The declining slope of the PDC plots reflects a reduction in adherence for all three groups. Relative to the adherence patterns in the copayment exempt group, there was clearly a larger decline among the all and some copayment groups after the copayment increase in the post-period.

Figure 1.

Mean Monthly Proportion of Days Covered for Lipid Lowering Medications by Copayment Status and Time

Table 2 summarizes the results on unadjusted outcomes by copayment group and time period. Both outcome measures were similar in the copayment exempt group and the some copayment group in the pre-period. Between 71 to 73 percent of the patients in these two groups were adherent (PDC>=80%) to lipid lowering medications in the pre-period and between 20 to 24 percent of the patients in these two groups had at least one continuous gap of 90 days or more in the pre-period. On the other hand, and as also reflected in Figure 1, adherence was significantly higher in the all copayment group with 83% of the patients identified as adherent and only 9% having a continuous gap of 90 days in the pre-period. After the increase in copayments, the percent of patients adherent to lipid lowering medications declined in all three groups. However, the percent of patients who were adherent in the post period declined significantly more in the all (-19.2%) and some (-19.3%) copayment groups relative to the copayment exempt group (-11.9%, p<0.05 for both comparisons). Similarly, the incidence of a continuous gap of 90 days increased at twice the rate in both the all copayment group (+24.6%) and some copayment group (+24.1%) relative to the copayment exempt group (+11.7%, p<0.0001 for both comparisons).

Table 2.

Unadjusted Outcomes by Copayment Status and Time Period

| Outcome by Copayment Status | Pre-period | Post-period | Difference (Post-Pre) | Difference in Difference | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adherent (PDC >=80%) | |||||

| Copay exempt | 72.7% | 60.8% | -11.9% | ||

| Some copay group | 70.9% | 51.6% | -19.3% | -7.4% | 0.023 |

| All copay group | 82.5% | 63.3% | -19.2% | -7.3% | <.001 |

| Continuous gap (90 days or more) | |||||

| Copay exempt | 23.6% | 35.4% | 11.7% | ||

| Some copay group | 20.0% | 44.0% | 24.1% | 12.3% | <.0001 |

| All copay group | 8.8% | 33.4% | 24.6% | 12.9% | <.0001 |

Note: Adherent defined as proportion of days covered (PDC) ≥ 80%

These results were confirmed in the multivariate analyses as illustrated by the adjusted odds ratios on the copayment group by post-period interaction terms (Table 3). After controlling for other factors, compared to the control group of copayment exempt veterans, the odds of being adherent in the post- period relative to the pre-period were significantly lower among the all copayment group (OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.47,-0.80) and the some copayment group (OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.57-0.95). Similarly, the odds of having a continuous gap of 90 days in the post-period relative to the pre-period were almost three times as high in the all copayment group (OR 3.04, 95% CI 2.29, 4.03) and twice as high in the some copayment group (OR 1.85, 95% CI 1.43, 2.40) when compared to the copayment exempt group.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Results: Adherent and Continuous Gap

| Adherent (PDC ≥ 80%) | Continuous gap (90-days or more) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-value | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| Some copay group | 0.87 | (0.70, 1.09) | 0.23 | 0.87 | (0.68, 1.10) | 0.24 | |

| All copay group | 1.44 | (1.12, 1.84) | 0.004 | 0.42 | (0.32, 0.55) | <.0001 | |

| Post period | 0.58 | (0.46, 0.74) | <.0001 | 1.76 | (1.39, 2.22) | <.0001 | |

| Some copay group*Post period | 0.73 | (0.57, 0.95) | 0.017 | 1.85 | (1.43, 2.40) | <.0001 | |

| All copay group*Post period | 0.61 | (0.47, 0.80) | <.001 | 3.04 | (2.29, 4.03) | <.0001 | |

| Age | 1.03 | (1.02, 1.03) | <.0001 | 0.98 | (0.97, 0.98) | <.0001 | |

| Female | 0.64 | (0.45, 0.91) | 0.014 | 1.66 | (1.14, 2.43) | 0.009 | |

| Zip-code level household income | 1.01 | (1.00, 1.01) | <.0001 | 0.99 | (0.99, 1.00) | <.0001 | |

| Medical conditions | |||||||

| Coronary artery disease | 0.99 | (0.90, 1.10) | 0.86 | 1.00 | (0.90, 1.11) | 0.99 | |

| Atherosclerosis | 1.03 | (0.87, 1.23) | 0.74 | 1.07 | (0.89, 1.29) | 0.47 | |

| Diabetes | 0.89 | (0.68, 1.15) | 0.37 | 0.90 | (0.68, 1.18) | 0.44 | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 0.98 | (0.81, 1.18) | 0.80 | 0.98 | (0.79, 1.20) | 0.82 | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1.03 | (0.88, 1.21) | 0.68 | 1.03 | (0.87, 1.22) | 0.74 | |

| Hypertension | 1.01 | (0.90, 1.13) | 0.88 | 0.96 | (0.85, 1.07) | 0.45 | |

| Number of distinct medication classes | 1.01 | (1.00, 1.03) | 0.05 | 0.99 | (0.97, 1.00) | 0.032 | |

| New user | 0.91 | (0.81, 1.01) | 0.09 | 1.44 | (1.28, 1.62) | <.0001 | |

Note: Adherent defined as proportion of days covered (PDC) ≥ 80%

Subgroup analysis indicated that the impact of the copayment increase was felt similarly among the three vulnerable groups (Table 4). Even among the subgroup of veterans at high CHD risk, the adjusted odds of having a continuous gap of 90 days in lipid lowering medication use in the post-period relative to the pre-period were almost twice in the some copayment group and three times in the all copayment group when compared to the copayment exempt group. Sensitivity analysis with the outcome of continuous gaps defined by 30-days, 60-days, or 120-days resulted in similar findings (Table 5). Furthermore, inclusion of data from the “washout” period and/or reducing the observation window from 24 months to 12 months for the pre- and post-period each did not substantially change the significance or magnitude of the results.

Table 4.

Logistic Regression Results: Subgroup Analyses

| Adherent (PDC ≥ 80%) | Continuous gap (90 days or more) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Odds Ratios | 95% CI | p-value | Adjusted Odds Ratios | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| High CHD Riska | |||||||

| Some copay group*Post | 0.75 | (0.55, 1.02) | 0.063 | 1.76 | (1.28, 2.40) | <.001 | |

| All copay group*Post | 0.63 | (0.46, 0.87) | 0.005 | 2.99 | (2.11, 4.22) | <.0001 | |

| High medication usersb | |||||||

| Some copay group*Post | 0.77 | (0.57, 1.03) | 0.079 | 1.65 | (1.23, 2.21) | 0.001 | |

| All copay group*Post | 0.56 | (0.39, 0.78) | 0.001 | 2.24 | (1.56, 3.23) | <.0001 | |

| Age 65 or older | |||||||

| Some copay group*Post | 0.71 | (0.51, 0.97) | 0.001 | 1.93 | (1.40, 2.66) | <.0001 | |

| All copay group*Post | 0.63 | (0.45, 0.87) | <.0001 | 2.98 | (2.12, 4.18) | <.0001 | |

Note: Adherent defined as proportion of days covered (PDC) ≥ 80%

Includes patients with history of coronary artery disease, atherosclerosis, diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease

Includes patients using ≥ 5 distinct medication classes

Table 5.

Logistic Regression Results: Sensitivity Analysis by Outcome and Study Period Definitions

| Adjusted Odd Ratios | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adherent | Continuous gap | ||||

| PDC>=80% | 30 days | 60 days | 90 days | 120 days | |

| 2-year pre- & post-analysis with washout period | |||||

| Some copay group*Post | 0.73* | 1.87** | 1.81** | 1.85** | 1.99** |

| All copay group*Post | 0.61** | 2.26** | 2.69** | 3.04** | 3.47** |

| 2-year pre- & post-analysis without washout period | |||||

| Some copay group*Post | 0.79 | 1.85** | 1.71** | 1.67** | 1.72** |

| All copay group*Post | 0.65** | 2.17** | 2.34** | 2.55** | 2.94** |

| 1-year pre- & post-analysis with washout period | |||||

| Some copay group*Post | 0.71** | 1.27 | 1.57** | 2.01** | 2.07** |

| All copay group*Post | 0.66** | 1.47** | 2.17** | 2.84** | 3.21** |

| 1-year pre- & post-analysis without washout period | |||||

| Some copay group*Post | 0.70** | 1.23 | 1.52** | 1.73** | 1.66** |

| All copay group*Post | 0.63** | 1.40** | 1.91** | 2.29** | 2.56** |

Note: Adherent defined as proportion of days covered (PDC) ≥ 80%

Significant at p-value <0.05

Significant at p-value <0.001

Discussion

The VA copayment increase from $2 to $7 adversely impacted lipid lowering medication adherence among veterans. The likelihood of being adherent, as measured by evidence of possession of lipid lowering medications for 80 percent or more of the observation period, significantly declined among veterans subject to copayments for some or all drugs as compared to veterans exempt from copayments. This decline in adherence was not just a result of short gaps in use interspersed between prescription refills. In fact, the copayment increase was accompanied by a significant increase in the likelihood of having continuous gaps of up to 120 days or more in lipid lowering medication use among veterans subject to copayments relative to those who were exempt. Gaps in use for such extended periods clearly have clinical implications and in fact have been termed as “discontinuation” of therapy in many medication adherence studies using prescription refill data. 16, 17 Of even greater concern was our finding that a similar adverse effect of the copayment increase was observed in groups at higher risk for CHD who were using these medications for either primary or secondary prevention.

Our study is the first to examine the impact of the VA copayment increase on lipid lowering medication adherence in veterans. Our findings on worsening adherence with lipid lowering medications are supported by previous studies that have evaluated the impact of increased cost sharing on statin adherence in other patient populations. 17-21 Most of these studies examined patients with employer-sponsored health insurance and the increase in their cost-sharing requirements was considerably higher than the VA copayment increase from $2 to $7. Nonetheless, we found a comparable or even larger negative impact on lipid lowering medication adherence in our sample of veterans.

Given that copayments in the private sector were much higher during this time period, with mean copayments from 2001 to 2004 increasing for generic drugs from $7 to $10 (42.9%), for preferred brand-name drugs from $13 to $21 (61.5%) and for nonpreferred brand-name drugs from $17 to $33 (94.1%) 1, 3, policymakers who proposed this VA copayment increase may have thought an increase of five dollars and the new copayment of $7 to be small enough to be unlikely to adversely affect utilization. However, the $2 to $7 increase more than tripled the out-of-pocket costs for veterans, who were likely to be lower in income than the patients affected by the changes in copayments in much of the private sector, and our study indicates that it did have a significant negative impact on adherence for at least one class of essential medications that has been shown to significantly reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Our findings have several important implications for VA policymakers. First, price sensitivity varies across different populations and small absolute changes in copayments may still have a significant impact on medication use in populations with lower socioeconomic status, as had been reported previously with even a 50 cent copayment increase among Medicaid patients.22 Hence, policymakers need to be cautious before implementing abrupt increases in copayments within low SES populations. Second, the benefits of a uniform VA copayment requirement which does not vary with the brand/generic status, cost, or clinical benefits of the drug could be debated.23 While the VA followed the private sector's prescription cost-containment strategy of increased cost-sharing, it has not embraced tiered copayments which are widely prevalent among employer-sponsored plans. This is particularly relevant in the case of statins, wherein two statins (simvastatin and pravastatin) have become available as generics since 2006 and are available at significantly lower prices to the Department of Veterans Affairs. Presumably, the VA could charge veterans lower copayments for such medications and thereby facilitate higher adherence with drugs from such essential medication classes. Furthermore, with the increasing availability of $4 generic drug programs from large discount department stores such as Walmart and Target since 2006, future increases in VA copayments that apply to both generics and brands will further drive veterans to fill some of their generics at such stores. This will limit reliable tracking of medication adherence among veterans using VA pharmacy refill records for both clinical and research purposes and may have important implications in terms of monitoring and improving quality of care and outcomes in veterans with chronic conditions. Finally, our finding that the increased copayment had an equally large adverse impact among patients at high CHD risk suggests that policymakers need to pay particular attention to the fact that a “one-size-fits-all” approach to designing cost-sharing policies that may adversely impact certain higher-risk patient groups. A more promising approach that has been proposed recently is to link copayments to individual patient need (specifically, lower patient copayments for higher expected therapeutic benefit and higher copayments for lower therapeutic benefit).23 In fact, a simulation-based study suggests that varying copayments for lipid lowering therapy by therapeutic need would increase adherence and reduce hospitalizations and emergency department use, resulting in total savings of more than $1 billion annually.21

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the study was limited only to veterans at the Philadelphia VAMC and the impact of the prescription copayment policy change may not be generalizable to other VA sites although there is no obvious reason why that would be the case. Second, we use prescription refill patterns as a proxy for medication adherence. Third, we only had access to prescription and medical services received within the VA system. Hence, the occurrence of continuous gaps of 90 days in lipid lowering medication use does not necessarily indicate that the veterans did not fill the prescription elsewhere, although it would be unlikely that many veterans could have obtained these prescriptions outside the VA system for less than $7 per month1, 3 given that all statins except for lovastatin were not available as generics during this time period. Fourth, the study was not a randomized experiment and hence unobserved differences between the copayment groups and copay exempt groups may have existed. Nevertheless, our pre-post study design with a contemporaneous control is considered a strong and valid observational study design. To the extent that the unobserved differences between the groups are time invariant our difference-in-difference analysis controls for them. Finally, the study did not evaluate whether the reduction in adherence due to the copayment increase had an adverse impact on cardiovascular outcomes or total medical expenditures. The clinical ramifications and medical cost consequences of reductions in adherence with such preventive chronic medications may not be immediately apparent and require data from several years of follow-up, although other work has suggested that the increased costs ensuing from prescription cost sharing for beneficial medications may substantially offset any short-term savings to payors. 24

Understanding the impact of this increase in copayments on health outcomes among veterans has clear policy relevance. In this era of large federal budget deficits it is clear that there will be ongoing pressure to reduce or at least constrain growth of the VA budget, and one of the approaches that the Congress may take to cut costs is through increases in VA prescription copayments. In January 2006, the VA prescription copayment was increased from $7 to $8. In fact, the President's FY2008 budget proposals and several previous years budget proposals had proposed increasing VA prescription copayments to $15 per 30-day supply.7, 8 While these proposals were not incorporated into legislation, determination of the societal impact of increases in copayments requires careful assessment of the impacts on prescription utilization and health outcomes among patients, particularly those at high risk. Such understanding is imperative to consider in future policy reform initiatives.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for funding support from the VA Center for Health Equity, Research and Promotion (CHERP), the American Heart Association Pharmaceutical Roundtable Award (Grant no. 0675066N), the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (Grant no. 540625), and the National Institute of Aging (R01 AG024451-01). The funding organizations or sponsors played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Clinical Perspective: Statins, the most commonly used lipid lowering agents, have been shown to significantly reduce the risk of future coronary events. Yet studies have shown that adherence to such lipid lowering drugs is suboptimal among patients in all age groups. This study showed that an increase in prescription copayments from $2 to $7 per 30-day drug supply among veterans significantly reduced adherence to lipid lowering medications. This decline in adherence was not just a result of short gaps in use interspersed between prescription refills. The copayment increase was accompanied by a significant increase in the likelihood of having continuous gaps of up to 120 days or more in lipid lowering medication use. This seemingly small five dollar increase, but more than tripling in copayments, adversely affected lipid-lowering medication adherence even among veterans at high risk for coronary heart disease.

Disclosures: Dr. Doshi has investigator-initiated research funding from Pfizer related to the use of cardiovascular medications. Dr. Doshi also reports owning stocks of Merck & Co., Inc. Dr. Kimmel has received funding for research and consulted for several pharmaceutical companies, including Pfizer, all unrelated to statins, in the past 2 years. Dr. Volpp has received investigator-initiated research funding from Pfizer related to the use of anti-hypertensive medications.

References

- 1.Employer Health Benefits: 2004 Annual Survey. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation and the Health Research and Educational Trust; 2004. Section 9: Prescription drugs and mental health benefits; pp. 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- 2.US General Accounting Office: Report to the Chairman, Committee on Veterans Affairs, House of Representatives. VA health care: Expanded eligibility has increased outpatient pharmacy use and expenditures. 2002 GAO-03-161. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibson TB, Ozminkowski RJ, Goetzel RZ. The effects of prescription drug cost sharing: A review of the evidence. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11:730–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldman DP, Joyce GF, Zheng Y. Prescription drug cost sharing: Associations with medication and medical utilization and spending and health. JAMA. 2007;298:61–69. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stroupe KT, Smith BM, Lee TA, Tarlov E, Durazo-Arvizu R, Huo Z, Barnett T, Cao L, Burk M, Cunningham F, Hynes DM, Weiss KB. Effect of increased copayments on pharmacy use in the department of veterans affairs. Med Care. 2007;45:1090–1097. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3180ca95be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeber JE, Grazier KL, Valenstein M, Blow FC, Lantz PM. Effect of a medication copayment increase in veterans with schizophrenia. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13:335–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pear R, Hulse C. Bush Budget Raises Drug Prices for Many Veterans. [Accessed September 24, 2008]; Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2005/02/07/politics/07budget.html?pagewanted=print&position=

- 8.Spotswood S. Enrollment Fees, Copays, Research Budget Still Matters For Contention In ‘08 VA Budget Proposal. [Accessed February 25, 2008]; Available at: http://www.usmedicine.com/article.cfm?articleID=1523&issueID=97.

- 9.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive summary of the third report of the national cholesterol education program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (adult treatment panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Avorn J, Monette J, Lacour A, Bohn RL, Monane M, Mogun H, LeLorier J. Persistence of use of lipid-lowering medications: A cross-national study. JAMA. 1998;279:1458–1462. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.18.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benner JS, Glynn RJ, Mogun H, Neumann PJ, Weinstein MC, Avorn J. Long-term persistence in use of statin therapy in elderly patients. JAMA. 2002;288:455–461. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jackevicius CA, Anderson GM, Leiter L, Tu JV. Use of the statins in patients after acute myocardial infarction: Does evidence change practice? Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:183–188. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rogers WH, Kazis LE, Miller DR, Skinner KM, Clark JA, Spiro A, 3rd, Fincke RG. Comparing the health status of VA and non-VA ambulatory patients: The veterans' health and medical outcomes studies. Journal of ambulatory care. 2004;27:249–262. doi: 10.1097/00004479-200407000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hiatt JG, Shamsie SG, Schectman G. Discontinuation rates of cholesterol-lowering medications: Implications for primary care. Am J Manag Care. 1999;5:437–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peterson AM, Nau DP, Cramer JA, Benner J, Gwadry-Sridhar F, Nichol M. A checklist for medication compliance and persistence studies using retrospective databases. Value Health. 2007;10:3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2006.00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andrade SE, Kahler KH, Frech F, Chan KA. Methods for evaluation of medication adherence and persistence using automated databases. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15:565–574. doi: 10.1002/pds.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneeweiss S, Patrick AR, Maclure M, Dormuth CR, Glynn RJ. Adherence to statin therapy under drug cost sharing in patients with and without acute myocardial infarction A population-based natural experiment. Circulation. 2007;115:2128–2135. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.665992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldman DP, Joyce GF, Escarce JJ, Pace JE, Solomon MD, Laouri M, Landsman PB, Teutsch SM. Pharmacy benefits and the use of drugs by the chronically ill. JAMA. 2004;291:2344–2350. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.19.2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huskamp HA, Deverka PA, Epstein AM, Epstein RS, McGuigan KA, Frank RG. The effect of incentive-based formularies on prescription-drug utilization and spending. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2224–2232. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa030954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gibson TB, Mark TL, Axelsen K, Baser O, Rublee DA, McGuigan KA. Impact of statin copayments on adherence and medical care utilization and expenditures. Am J Manag Care. 2006;(12):SP11–SP19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldman DP, Joyce GF, Karaca-Mandic P. Varying pharmacy benefits with clinical status: The case of cholesterol-lowering therapy. Am J Manag Care. 2006;12:21–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson AA, Jr, Reeder CE, Dickson WM. The effect of a medicaid drug copayment program on the utilization and cost of prescription services. Med Care. 1984;22:724–736. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198408000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fendrick AM, Smith DG, Chernew ME, Shah SN. A benefit-based copay for prescription drugs: Patient contribution based on total benefits, not drug acquisition cost. Am J Manag Care. 2001;7:861–867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsu J, Price M, Huang J, Brand R, Fung V, Hui R, Fireman B, Newhouse JP, Selby JV. Unintended consequences of caps on medicare drug benefits. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2349–2359. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa054436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]