Abstract

PURPOSE

To determine whether magnetic resonance (MR) spectroscopic imaging reveals metabolic changes, especially decreased N-acetylaspartate (NAA) concentrations outside the medial temporal lobe in patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), consistent with neuropathologic findings of extratemporal neuronal impairment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Eleven patients with mesial TLE and 13 control subjects were examined with multisection MR spectroscopic imaging. Three MR spectroscopic imaging sections were acquired. Thirteen brain regions in each hemisphere and the midbrain were analyzed in each patient, and the NAA to creatine-phosphocreatine (Cr) plus choline-containing compounds (Ch) (NAA/[Cr + Ch]) ratios were determined. In addition, hemispheric and whole-brain values were calculated and statistically analyzed.

RESULTS

The NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio in the ipsilateral hippocampus was significantly reduced, compared with that in the contralateral hippocampus (P < .002) and compared with that in control subjects (P < .03), confirming findings in previous studies. In patients, whole-brain NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio outside the hippocampus was significantly lower than that in control subjects (P < .002). For the ipsilateral hemisphere in patients, NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio was significantly lower than that in control subjects (P < .0002). Comparisons between individual brain regions revealed trends toward lower NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratios in many areas of the ipsilateral and, to a lesser extent, the contralateral hemisphere outside the hippocampus and temporal lobe, suggesting diffuse impairment.

CONCLUSION

Results suggest that repeated seizure activity damages neurons outside of the seizure focus.

Keywords: Brain, metabolism, 1341.99, Brain, MR, 1341.121411, 1341.12145, Epilepsy, 1341.83, Hippocampus, 1341.83, Magnetic resonance (MR), spectroscopy, 1341.12145

To optimally plan surgical treatment of patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), it is necessary to determine the location and size of the focus and the extent to which other regions of the brain are also affected. A variety of imaging modalities have been used to evaluate mesial TLE; among these are magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, positron emission tomography (PET), and MR spectroscopy. Because it is thought that in mesial TLE the seizure focus is localized to the hippocampus, most MR spectroscopic studies thus far were performed in the hippocampal and/or the medial temporal lobe region. Findings obtained at our laboratory (1-3) and those of others (4-9) previously demonstrated that concentrations of the neuronal marker N-acetylaspartate (NAA) were reduced in the ipsilateral hippocampus in patients with mesial TLE and, thus, that MR spectroscopy can be used to lateralize the seizure focus. However, little is known about possible changes in metabolite concentrations in brain regions outside the hippocampi and the medial temporal lobe.

Several observations suggest that mesial TLE may affect brain regions outside of the medial temporal lobe. In a neuropathologic study in patients with TLE, Margerison and Corsellis (10) observed hypoxic damage that scattered far beyond the confines of a single temporal lobe. In addition, extrahippocampal volume abnormalities were observed at MR imaging performed in patients with TLE (11-13). The volume deficits were bilateral and did not lateralize the epileptogenic hemisphere. PET study findings showed metabolic abnormalities in regions remote from the focus (14-18). Diffuse metabolic changes in the contralateral hemisphere in patients with mesial TLE were observed in a phosphorus 31 (31P) MR spectroscopic imaging study (19). Finally, we (2,3) and others (7,9,20,21) reported reductions of NAA concentrations in the contralateral hippocampus in patients with mesial TLE. These reductions of NAA concentrations in the contralateral hippocampus could be due to bilateral medial temporal sclerosis or repeated seizure activity that might cause neuronal loss or injury, as reflected by a decreased NAA concentration. In addition, several groups (20-23) have reported that the contralateral hippocampal NAA concentration increased after surgery for epilepsy. Altogether these findings suggest that repeated seizures might produce temporary metabolic changes or damage to neurons outside the focus and that this might result in reversible NAA concentration decreases. If repeated seizure activity is responsible for reduced contralateral NAA concentrations, then NAA concentrations might also be reduced in other regions outside the hippocampus. This concept might help explain the general cognitive impairment observed in patients with mesial TLE (24,25), which is not well understood.

Findings in an MR spectroscopic imaging study of Li et al (26) indicated a reduced NAA to creatine-phosphocreatine (Cr) ratio in frontocentroparietal regions in patients with TLE. The overall purpose of our study was to determine whether MR spectroscopic imaging can be used to detect metabolic changes, especially decreased NAA concentrations in different areas outside the medial temporal lobe in patients with mesial TLE, that are consistent with neuropathologic findings of extratemporal neuronal impairment (10). The specific goals were to verify previous findings of reduced NAA concentrations in the ipsilateral hippocampus at multisection MR spectroscopic imaging in patients with mesial TLE; to determine whether NAA concentrations are reduced in other brain regions outside the hippocampus; and if such changes exist, to determine whether NAA concentration changes are widespread or localized and whether they are mainly unilateral or bilateral.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

We examined 11 consecutive patients referred to the Northern California Comprehensive Epilepsy Center, University of California, San Francisco. This group included six men and five women (mean age, 36.6 years ± 7.3 [SD]) with medically refractory unilateral mesial TLE. The study was approved by the local Committee on Human Research, and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. All of the patients had clinical histories, seizure symptoms, ictal and interictal electrophysiologic and neuroimaging findings that were consistent with unilateral mesial TLE (27). Demographic and clinical data in the patients were obtained at the Northern California Comprehensive Epilepsy Center by one author (K.D.L.). The seizure focus was localized by means of scalp (including sphenoidal electrodes) and, as necessary, subdural electrode recordings, which were used to determine the ipsilateral side.

Only patients whose ictal recordings demonstrated either localized voltage attenuation or rhythmic sharp activity that preceded or coincided with the clinical onset of the seizure were included. All patients underwent separate independent MR imaging, and findings were interpreted by a neuroradiologist. MR imaging results were consistent with electroencephalographic results in nine of 11 patients and were classified as not lateralized in two patients. In three of 11 patients, no hippocampal atrophy was detected. The seizure frequency was between one and 30 seizures per month (mean, 7 seizures ± 8). The duration of epilepsy ranged from 15 to 41 years (mean, 29 years ± 9). Six of the 11 patients underwent surgery for seizures, and all six patients were seizure free more than 1 year since surgery.

The patients were compared with 13 healthy control subjects who were identified as healthy on the basis of their own statements and a review of their medical histories. Potential control subjects with medical conditions known to affect the central nervous system, with a history of spells that might suggest prior seizures, or with a history of any involvement of the central nervous system were excluded. Control subjects included five men and eight women. The age range was 19−46 years (mean age, 32.5 years ± 7.9).

Measurements

Proton multisection MR spectroscopic imaging spectra were acquired with a 1.5-T unit (Magnetom Vision; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) by using a standard circularly polarized head coil. After scout imaging in coronal and sagittal orientations, T1-weighted spin-echo MR images (repetition time msec/echo time msec, 500/14; section thickness, 3 mm) were obtained with angulation parallel to the long axis of the hippocampus for localization in the transverse plane. In addition, an oblique transverse T2-weighted spin-echo data set (2,550/20, 80; section thickness, 3 mm) was acquired with angulation along the optical nerve.

After global shimming, three 15-mm sections were measured. One section was acquired with angulation parallel to the T1-weighted images and included both hippocampi (Fig 1). The other two sections were acquired with alignment parallel to the T2-weighted images; the lower section just included the corpus callosum and the other was slightly above the corpus callosum (Fig 1). Section-selective inversion pulses (inversion time, 170 msec) were used to reduce contamination of the MR spectra with lipid resonances. The equivalent of 36 × 36 phase-encoding steps over a circular k-space region was used (28), and this yielded a nominal voxel size of 8 × 8 × 15 mm3. The data were acquired with a repetition time of 1,800 msec and an echo time of 140 msec, and the measurement time was 35 minutes.

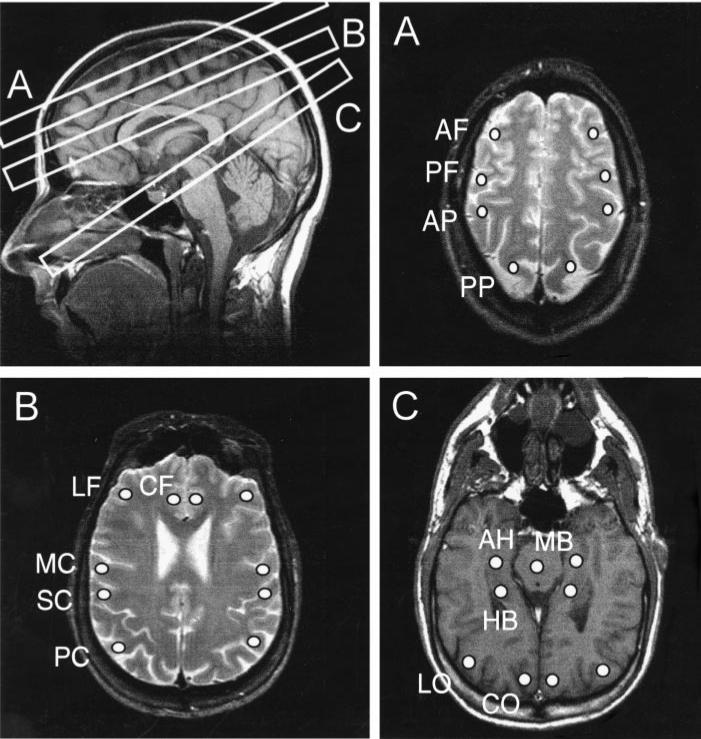

Figure 1.

Upper left: Sagittal T1-weighted MR image (500/14; flip angle, 70°) indicates the positions of the three MR spectroscopic imaging sections (A–C). A–C, The three MR spectroscopic imaging sections are displayed on top of corresponding MR images. Two MR spectroscopic imaging sections (A, B) were acquired with angulation along the optic nerve. One section (C) was acquired with angulation along the long axes of the hippocampi. The positions in the MR spectroscopic imaging sections where the spectra were derived are also indicated. A and B were T2-weighted MR images (2,550/80), and C was a T1-weighted MR image (500/14; flip angle, 70°). AF = anterior frontal lobe, AH = anterior hippocampus, AP = anterior parietal lobe, CF = central frontal lobe, CO = central occipital, HB = hippocampal body, LF = lateral frontal lobe, LO = lateral occipital, MB = midbrain, MC = motor cortex, PC = parietal cortex, PF = posterior frontal lobe, PP = posterior parietal lobe, SC = sensory cortex.

Postprocessing

The MR spectroscopic imaging data were zero filled to 64 × 64, and mild apodization in the spatial domain was applied; this resulted in an effective voxel size of about 1.4 cm3. Postprocessing of the time domain data included zero filling to 1,024 data points and apodization with a Gaussian function corresponding to 2-Hz line-broadening in the frequency domain. Water signal removal, spectral phasing following Fourier transformation, and polynomial baseline correction also were performed. The signals for NAA, Cr, and choline-containing compounds (Ch) were quantitated by means of curve fitting, and the area under the curve was used for analysis. The data were analyzed by using standard spectroscopy software (Luise; Siemens). Because findings in a previous study about mesial TLE performed in our laboratory suggested that, of all metabolite ratios, the NAA to Cr plus Ch (NAA/[Cr + Ch]) ratio provided the greatest change (2), this ratio, therefore, also was used in this study.

Figure 1 displays the regions for multisection MR spectroscopic imaging voxel selection. The selection of individual voxels and processing of the spectra were performed with blinding to the seizure lateralization findings (one author [P.V.] was responsible for voxel selection; another [G.B.M.] was responsible for blinding). The voxel selection was performed by using anatomic landmarks marked on a template. Although the possibility of slight voxel positioning variations was associated with this procedure, the blinded analysis ensured an unbiased processing.

A total of 27 single voxels from 13 different brain regions in each hemisphere and one from the midbrain were analyzed in each patient by one of us (P.V.). The regions were chosen before any results were known, and they were chosen with the main focus on regions (except the midbrain) that were most likely to enhance the lateralization ability of MR spectroscopic imaging. The midbrain, in addition, was analyzed to investigate possible nonlateralizing metabolic changes. As a threshold for inclusion of spectra, we used a signal-to-noise ratio of at least 4 for NAA signal intensities and a ratio of less than 1.2 and greater than 0.8 between the fitted line width of NAA and the mean line width of Cr and Ch.

The regions were chosen to include predominantly gray matter, although white matter was included to some degree in several regions. The spectral quality in the most anterior part of the lateral temporal lobe was generally inadequate for spectral quantitation, and this region, therefore, was excluded from the analysis. Brain regions for voxel selection included the left and right hippocampi, the midbrain and the occipital regions in the section that included the hippocampus, and the spectra from the left and right frontal and parietal regions in the two upper sections (Fig 1).

Calculation of NAA/(Cr + Ch) Ratio

NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratios were calculated for all selected voxel positions. Two different analyses were performed.

Analysis 1

In each subject (patients and control subjects), a single mean NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio (whole-brain ratio) and in all patients an ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheric mean value were calculated from the ratios of all voxels outside the hippocampus. The NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratios of the different brain regions were first normalized by weighting with the mean value of control subjects at the same position. This procedure accounts for inherent regional NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio differences when the whole-brain and hemispheric mean values were calculated and helps to avoid calculation of different values because of missing values in some regions. The normalized ratios from all selected voxels outside the hippocampus (ratios from right and left sides of 11 different brain regions) were averaged to calculate the whole-brain ratio in each subject. In addition, in each patient, the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheric mean values were calculated by averaging all NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratios of one hemisphere outside the hippocampus.

Analysis 2

A mean NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio for each position in the brain was calculated for each group (ie, the ipsilateral side in patients, the contralateral side in patients, and the control subjects) by averaging all ratios of an individual voxel position without normalization.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of the MR spectroscopic imaging data was performed by using one-way analysis of variance with software (SAS; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) to compare the NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratios in all three groups, that is, the ipsilateral hemisphere in patients, the contralateral hemisphere in patients, and the control subjects. For comparisons of pairs of groups, one-tailed paired (ipsilateral side in patients vs contralateral side in patients) and unpaired (patients vs control subjects) t tests were performed. The use of a one-tailed instead of a two-tailed t test was justified on the basis of previously reported NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio reductions in patients with TLE. A P value of less than .05, after correction for multiple comparisons according to Bonferroni (SAS/SAT User's Guide, release 6.03 edition, 1988), was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference for comparisons of whole-brain and hemispheric mean values between patients and control subjects.

In contrast, comparisons for all different individual brain regions among patients (ipsilateral side and contralateral side) and control subjects were presented without corrections for multiple comparisons to possibly reveal subtle differences despite numerous comparisons. However, these findings are presented as trends only. For the comparisons of spectra from the hippocampal region, no corrections for multiple comparisons were necessary, because this analysis was based on a different hypothesis. Pearson product moment correlation coefficients were used to test correlations. All data were presented as the mean ± 1 SD.

No correlation analyses between outcome after surgery and MR spectroscopic imaging results could be performed, because all patients who underwent surgery were seizure free. Furthermore, no correlation analyses between neuropsychiatric data and MR spectroscopic imaging results were performed, because neuropsychiatric data were available for only seven of the 11 patients, and of these seven patients, four had similar NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratios.

RESULTS

Clinical Data and Quality of Spectra

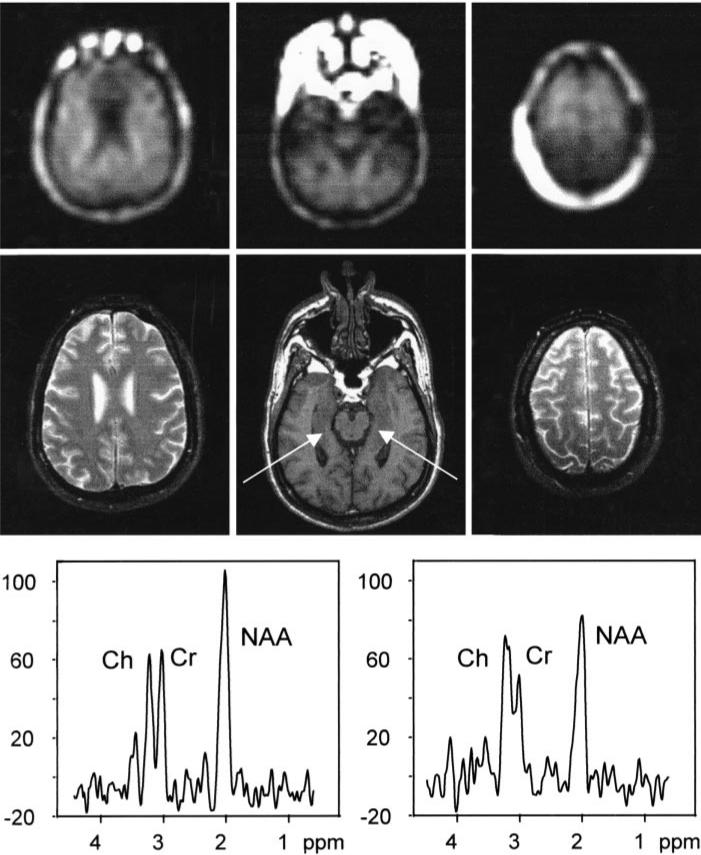

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical data in 11 patients. Figure 2 shows three NAA metabolite images from the MR spectroscopic imaging measurement in a representative patient with mesial TLE, with the corresponding MR images for anatomic guidance. In addition, spectra from the hippocampi are shown. The spectrum from the left hippocampus shows a clearly reduced NAA signal intensity, compared with the spectrum from the right hippocampus. This example demonstrates the good spectral quality of the measurements.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Patients and Individual Relative Hemispheric Mean NAA/(Cr + Ch) Ratios

| Patient No./Age (y)/Sex | Hippocampal Atrophy | Age at Onset | No. of Seizures per Month | Outcome after Surgery | Hemispheric Mean NAA/(Cr + Ch) Ratio |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ipsilateral | Contralateral | |||||

| 1/39/M | No | 19 y | 10 | Not performed | 0.84 | 1.01 |

| 2/52/M | Yes | 12 y | 3 | Not performed | 0.87 | 0.87 |

| 3/43/F | No | 2 y | 1 | Seizure free | 0.92 | 1.10 |

| 4/28/M | Yes | 13 y | 2 | Seizure free | 0.89 | 1.02 |

| 5/28/F | Yes | 2 y | 5 | Seizure free | 0.96 | 0.84 |

| 6/33/M | Yes | 1 y | 9 | Seizure free | 0.77 | 0.90 |

| 7/39/F | No | 6 y | 1 | Not performed | 0.90 | 0.88 |

| 8/38/F | Yes | 13 y | 2 | Not performed | 0.93 | 0.91 |

| 9/29/M | Yes | 14 y | 30 | Seizure free | 0.86 | 0.95 |

| 10/34/F | Yes | 6 mo | 10 | Seizure free | 0.88 | 0.88 |

| 11/40/M | Yes | 3 y | 7 | Not performed | 0.89 | 0.90 |

Note.—Hemispheric mean NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratios were obtained by using analysis 1 and calculated without ratios from voxels that included the hippocampi in all patients (ipsilateral and contralateral values). In control subjects, the mean age was 32.5 years, and the whole-brain mean NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio ± SD was 0.98 ± 0.04 (calculated from 11 whole-brain mean ratios).

Figure 2.

Multisection MR spectroscopic imaging measurements in a representative TLE patient. Top row: Three oblique transverse NAA metabolite images. Center row: Corresponding MR images displayed for anatomic guidance. The sections were acquired with angulation as stated for Figure 1. Bottom row: Two spectra obtained from hippocampal tissue as indicated by the arrows on the center MR image in the center row. Parameters for the MR images in the center row were 500/14 and flip angle of 70° for the center image and 2,550/80 for the left and right images.

Comparison of NAA/(Cr + Ch) Ratios in the Hippocampal Regions

Table 2 summarizes results for individual voxel positions. In eight of the 11 patients, spectra from both hippocampi in the area of the hippocampal body could be analyzed; in the remaining three subjects, the spectral quality in at least one hippocampus was insufficient, according to the applied threshold for including spectra. The ipsilateral hippocampal NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio was lower in all eight patients compared with that of the contralateral side. The mean ipsilateral hippocampal body NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio was 0.62 ± 0.11 compared with 0.79 ± 0.11 in the contralateral side (P < .002, Table 2). The ipsilateral hippocampal NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio also was smaller than the ratio in control subjects (P < .03). In contrast to findings in our previous reports (2,3), contralateral NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio in the hippocampal body was not different from that in control subjects (0.79 ± 0.11 compared with 0.72 ± 0.07, respectively; P > 0.05). In the very anterior part of the hippocampus, the ipsilateral and contralateral NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratios in patients were lower than the ratios in control subjects. However, because of the poorer spectral quality in this region, analysis of spectra was possible in only a few patients, and the differences were not statistically significant.

TABLE 2.

Mean NAA/(Cr + Ch) Ratios for Voxel Positions

| Mean NAA/(Cr + Ch) Ratio ± 1 SD* |

P Values† |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voxel Position | Controls | Ipsilateral Side in Patients | Contralateral Side in Patients | Controls versus Ipsilateral Side in Patients | Controls versus Contralateral Side in Patients | Ipsilateral versus Contralateral Side in Patients |

| Anterior frontal lobe | 1.07 ± 0.14 (13) | 0.91 ± 0.16 (10) | 0.99 ± 0.19 (11) | .011‡ | >.1 | .028‡ |

| Posterior frontal lobe | 1.07 ± 0.15 (13) | 0.99 ± 0.08 (11) | 1.01 ± 0.24 (9) | .044‡ | >.1 | >.1 |

| Anterior parietal lobe | 1.10 ± 0.10 (13) | 1.07 ± 0.16 (11) | 1.09 ± 0.12 (10) | >.1 | >.1 | >.1 |

| Posterior parietal lobe | 1.09 ± 0.09 (12) | 1.00 ± 0.11 (9) | 1.04 ± 0.14 (8) | .029‡ | >.1 | >.1 |

| Anterior hippocampus | 0.60 ± 0.15 (11) | 0.48 ± 0.15 (4) | 0.53 ± 0.10 (6) | >.1 | >.1 | >.1 |

| Hippocampal body | 0.72 ± 0.07 (12) | 0.62 ± 0.11 (9) | 0.79 ± 0.11 (9) | .025‡ | >.05 | .0017‡ |

| Midbrain | 0.96 ± 0.14 (8) | 0.82 ± 0.09 (8) | 0.82 ± 0.09 (8) | .016‡ | ND | ND |

| Lateral occipital lobe | 1.01 ± 0.16 (10) | 0.88 ± 0.16 (9) | 1.05 ± 0.25 (7) | .048‡ | >.1 | >.1 |

| Central occipital lobe | 1.13 ± 0.17 (9) | 0.96 ± 0.26 (8) | 0.97 ± 0.18 (9) | >.06 | .034‡ | >.1 |

| Lateral frontal lobe | 1.02 ± 0.07 (13) | 1.03 ± 0.19 (10) | 1.00 ± 0.24 (10) | >.1 | >.1 | >.1 |

| Central frontal lobe | 0.79 ± 0.17 (7) | 0.67 ± 0.08 (3) | 0.69 ± 0.15 (3) | >.09 | >.1 | >.06 |

| Motor cortex | 1.02 ± 0.08 (13) | 0.96 ± 0.15 (10) | 1.00 ± 0.16 (11) | >.1 | >.1 | >.1 |

| Sensory cortex | 1.02 ± 0.10 (13) | 0.86 ± 0.08 (9) | 1.02 ± 0.21 (11) | .0004‡ | >.1 | .026‡ |

| Parietal cortex | 1.11 ± 0.10 (13) | 1.01 ± 0.19 (11) | 1.01 ± 0.13 (10) | >.06 | .032‡ | >.1 |

Numbers in parentheses are numbers of measurements for each position.

P values are for a one-tailed t test without corrections for multiple comparisons.

Differences were not statistically significant because the values were determined without correction for multiple comparisons.

Comparison of Mean NAA/(Cr + Ch) Ratios from Whole Brain and from Ipsilateral and Contralateral Hemispheres Outside the Hippocampus

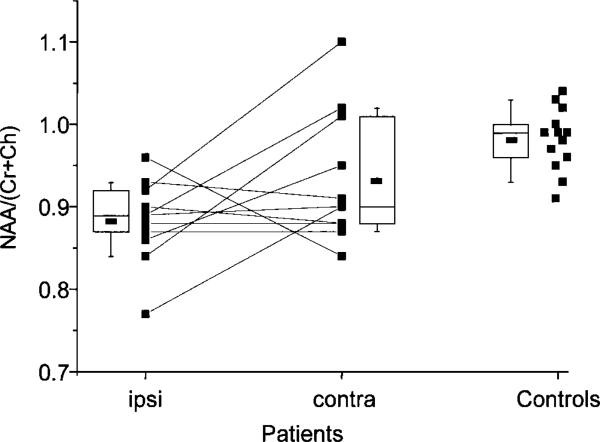

Table 1 and Figure 3 show the hemispheric metabolite values in all patients and whole-brain values in control subjects. In Table 3, whole-brain NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratios outside the hippocampus are compared between patients and control subjects. Hemispheric values are compared among patients (ipsilateral hemisphere and contralateral hemisphere), and hemispheric values of patients are compared with whole-brain ratios of control subjects. The whole-brain NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratios outside the hippocampus were 0.98 ± 0.04 in control subjects and were significantly reduced to 0.90 ± 0.06 in patients with mesial TLE (P < .002). Analysis of variance indicated a significant group effect for the hemispheric mean values (P < .002, patients [ipsilateral hemisphere and contralateral hemisphere] and control subjects).

Figure 3.

Graphic comparison of ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheric mean NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratios in all patients and whole-brain ratios in control subjects calculated without values from voxels that included the hippocampus. The boundaries of the boxes indicate the 25th and the 75th percentiles, and the line within the box marks the median. Error bars indicate the 90th and 10th percentiles. Ipsilateral and, to a lesser extent, contralateral hemispheric values for most patients were lower than they were in control subjects. The ipsilateral value is clearly reduced compared with the contralateral value in five patients. In five patients, the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheric values were almost identical, and in one patient, the ipsilateral ratio was clearly higher than was the contralateral ratio.

TABLE 3.

Mean NAA/(Cr + Ch) Ratios Averaged over Whole Brain and over Hemispheres in Patients and Control Subjects

| Area and Subjects | Mean Ratio ± 1SD |

|---|---|

| Whole head | |

| Controls | 0.98 ± 0.04 |

| Patients | 0.90 ± 0.06 |

| Hemisphere | |

| Patients | |

| Ipsilateral hemisphere | 0.88 ± 0.05 |

| Contralateral hemisphere | 0.93 ± 0.08 |

Note.—Values were calculated without ratios from voxels that included the hippocampi. P values for a one-tailed t test with correction for multiple comparisons were as follows: for the whole brain, patients versus controls, <.002 (statistically significant); for the hemisphere—ipsilateral hemisphere in patients versus controls, <.0002 (statistically significant); contralateral hemisphere in patients versus controls, >.05; ipsilateral versus contralateral hemisphere in patients, >.05.

Ipsilateral hemispheric mean values in patients were 0.88 ± 0.05, compared with 0.98 ± 0.04 for whole-brain values in control subjects (P < .0002, Table 3). The contralateral hemispheric values were 0.93 ± 0.08, and they also were considerably lower than whole-brain values in control subjects; however, the difference was not statistically significant after correction for multiple comparisons. The ipsilateral hemispheric values also were lower than the contralateral hemispheric values, although this difference was not statistically significant. Figure 3 shows that for most patients, the ipsilateral and contralateral values were lower than the whole-brain values in control subjects. However, in only five patients was the ipsilateral value clearly reduced by more than 10%, compared with the contralateral value. In five patients, the hemispheric ipsilateral and contralateral values were almost identical (ie, asymmetry between ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres, less than 3%), and in one patient the ipsilateral ratio was more than 10% greater than the contralateral ratio. This patient also exhibited the smallest difference between ipsilateral and contralateral hippocampal NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratios.

In two of three patients without hippocampal atrophy, the hippocampal NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio clearly indicated a lower ipsilateral ratio than a contralateral ratio; in the third patient, no contralateral hippocampal value could be obtained. However, the hemispheric NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratios were similar to those in patients with hippocampal atrophy (Table 1).

Comparison of NAA/(Cr + Ch) Ratios in Individual Brain Regions

The reduced NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratios observed in the whole brain outside the hippocampus could be due to widespread or focal NAA concentration losses. To detect focal NAA concentration loss, we compared the ratios of individual voxel positions among patients (voxels obtained from the ipsilateral side and the contralateral side) and control subjects (Table 2). Mean ipsilateral NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratios in patients were lower in 10 of 11 different brain regions outside the hippocampus compared with the control mean for these regions. In five of 11 brain regions outside the hippocampus (ie, the anterior frontal, posterior frontal, posterior parietal, and lateral occipital lobes and the sensory cortex), these ipsilateral NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratios were reduced compared with those of control subjects, with a P value less than .05 (calculated with a one-tailed t test without correction for multiple comparisons). In addition, the NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio in the midbrain was lower in patients than it was in control subjects. In 10 of 11 brain regions outside the hippocampus, the mean ipsilateral NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio also was lower compared with that in the corresponding contralateral regions, and the difference between ipsilateral and contralateral ratios was less than .05 in the anterior frontal lobe (P < .03) and the sensory cortex (P < .03), with a one-tailed paired t test without correction for multiple comparisons (Table 2). The contralateral NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio was lower than the ratio for control subjects in nine of 11 regions outside the hippocampus, with that in two of 11 regions (ie, the central occipital lobe and the parietal cortex) being reduced compared with that in controls, with a P value less than .05 (one-tailed paired t test without correction for multiple comparisons).

Because the characteristics of the NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio reductions in patients with mesial TLE outside the medial temporal lobe were widespread and nonfocal and because the reductions tended to be bilateral rather than unilateral, the differences between ipsilateral and contralateral ratios of individual voxels were small. Therefore, although most individual brain regions outside the hippocampus demonstrated a slightly lower ipsilateral NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio compared with the contralateral side, the results did not assist in seizure focus lateralization and did not improve the lateralization obtained with spectra from hippocampal regions alone.

Correlations between NAA/(Cr + Ch) Ratios in the Hippocampus with Those in Other Brain Regions

We correlated the NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratios in ipsilateral hippocampus with ipsilateral ratios in individual brain regions outside the medial temporal lobe, as well as with the whole-brain and hemispheric ratios. The NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio in the central frontal lobe and the ipsilateral hippocampus correlated positively (r = 0.76, P < .05, without correction for multiple comparisons), whereas NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratios in other regions and in the whole brain and the ipsilateral hemisphere were not significantly correlated with the hippocampal values.

DISCUSSION

The major findings of this study were as follows: (a) In patients with mesial TLE, NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratios are reduced in many regions outside the hippocampus and the temporal lobe, which presumably reflects loss of NAA concentration. (b) The NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio reduction outside the hippocampus is greatest in ipsilateral regions of the brain, compared with that in the contralateral side and compared with that in control subjects. (c) The NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratios in contralateral regions of the brain outside the medial temporal lobe are also reduced, compared with those in control subjects. (d) Previously reported reduced ipsilateral hippocampal NAA concentration in patients compared with that in contralateral hippocampus and control subjects was again confirmed.

In patients, the ipsilateral hippocampal NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio was reduced, compared with that in contralateral hippocampus and control subjects. When results in both hippocampi could be obtained, all patients were lateralized correctly on the basis of the lower ipsilateral NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio, compared with the contralateral ratio. The reduced hippocampal NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio could be due to neuron loss and gliosis or neuronal dysfunction. These findings obtained with multisection MR spectroscopic imaging confirm findings in previous studies (1-9), which solely measured hippocampal tissue and/or parts of the temporal lobe. In contrast to findings in previous studies (2,3,7,9,20,24), however, the contralateral hippocampal NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio in the hippocampal body was not different from the ratio in control subjects, whereas in the anterior hippocampus, there was a trend of lower contralateral NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratios compared with the ratios in control subjects. This could be due to the relatively small sample size, or it may reflect the finding of antero-posterior hippocampal differences in the ratios between patients and control subjects (29).

In an MR spectroscopic imaging study in regard to patients with TLE before and after surgery, Cendes et al (21) determined that NAA/Cr ratio loss is widespread in the ipsilateral temporal lobe in patients with TLE and extends beyond the regions of abnormality, as usually observed by using conventional MR imaging. Similarly, Li et al (26) demonstrated reduced NAA/Cr ratio in frontocentroparietal regions in patients with TLE. The findings of this study imply that, in addition, the NAA concentration is reduced in many other areas outside the hippocampal region and the temporal lobe. The largest NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio reductions were observed in the ipsilateral hemisphere in patients with mesial TLE, in addition to smaller NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio losses in different regions of the contralateral hemisphere when the ratios were compared with those in control subjects. These results suggest a diffuse impairment of the brain in patients with mesial TLE.

These findings are consistent with those in a neuropathologic study (10) in patients with TLE. In that study, it was determined that although the greatest abnormalities were observed in the medial temporal area, these abnormalities were not confined to the temporal region. Instead, the brain was usually bilaterally affected in a number of different areas, including the cerebral cortex, the subcortex, and the cerebellum. Similarly, in an MR imaging study (11) in patients with TLE extrahippocampal volume abnormalities were observed bilaterally. Furthermore, in a 31P MR spectroscopic imaging study in patients with TLE, van der Grond et al (19) detected diffuse metabolite changes in the contralateral hemisphere besides ipsilateral abnormalities. Unexpectedly, the contralateral changes were in the opposite direction, compared with the ipsilateral changes. In addition, findings in PET studies (15-17) in patients with TLE revealed widespread impairment that was evidenced by hypometabolism of regions outside the temporal lobe.

The NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratios in most brain regions in the ipsilateral hemisphere were lower than the ratios in corresponding contralateral regions. However, these differences were statistically significant in only two brain regions outside the hippocampus, probably because the contralateral hemisphere was impaired also. Therefore, the current approach of selection of voxels from defined brain regions did not improve the seizure focus lateralization over use of only spectra from hippocampal regions or the temporal lobe. This result is consistent with an MR imaging finding that the pattern of extrahippocampal volume deficits did not lateralize the epileptogenic hemisphere because the deficits were present bilaterally (11). However, the trend of a reduced ipsilateral NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio compared with a contralateral ratio in individual brain regions and a trend of reduced ipsilateral compared with contralateral hemispheric values indicates that the analysis of all acquired voxels improves the statistical power and may therefore assist in seizure focus lateralization.

The results clearly indicate that the multisection sequence is capable of detection of NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio reductions in many brain areas. The ability to access most parts of the brain may help in seizure focus localization, especially in patients with neocortical epilepsy in whom the focus is outside the hippocampus.

Findings in previous studies from our laboratory (2,3) and in those of others (3,7,9) have suggested that the NAA concentration in the contralateral hippocampus is reduced in patients with mesial TLE. Furthermore, findings in studies (21,23) concerning patients with mesial TLE before and after surgery indicate that an initially reduced NAA concentration in the contralateral hippocampus recovers after surgery. A possible explanation for this recovery is that neuron impairment on the contralateral side is secondary to ipsilateral seizure activity rather than due to bilateral hippocampal sclerosis (23). The finding of a widespread reduced NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio outside the hippocampus and the temporal lobe supports this hypothesis. The results suggest that besides the direct impairment of the ipsilateral hippocampus, ipsilateral epileptiform discharges lead to a diffuse impairment of the ipsilateral and, to a smaller extent, the contralateral hemisphere, and this impairment probably represents a neuronal dysfunction rather than a neuronal loss.

This concept is in contrast to findings in an earlier MR spectroscopic imaging study (3) of neocortical epilepsy with extratemporal seizure origin in which no reduction of hippocampal NAA concentration was established. Mechanistic differences in seizure propagation between patients with neocortical epilepsy and those with mesial TLE could be responsible for the different findings. Alternatively, the diffuse metabolic changes in patients with mesial TLE could be due to long-term effects of the drugs the patients were receiving. However, the previously obtained finding of an unchanged hippocampal NAA concentration occurred in patients with neocortical epilepsy who were receiving anticonvulsants in dosages similar to those that the patients with mesial TLE were receiving. This suggests that the treatment is not responsible for the detected changes. Further studies are underway to determine whether the preoperative extratemporal impairment improves after surgery.

Similar to findings in PET studies indicating that there was no correlation between hypometabolism in different regions of the brain and the severity of hippocampal neuron loss (16), our findings indicated that there were no significant correlations between the NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio from regions outside the hippocampus and the values from the hippocampal regions.

The current study has several limitations: First, while the spectra of most measured regions in the brain yielded excellent spectral quality, there were several regions that consistently did not produce acceptable spectral quality, according to the applied threshold. These regions included the anterior lateral temporal lobe (which was not included in the analysis) and anterior hippocampus and central frontal lobe (with only 50% and 30% of the spectra, respectively, within the quality threshold). These regions are subject to susceptibility gradients from the air-to-tissue interface of the sinuses. A simultaneous measurement together with that of other brain regions yielding high spectral quality is therefore not possible without the use of special techniques (eg, acquisition of multiple spin echoes).

Second, we did not determine absolute metabolite concentrations. Therefore, the detected changes in the NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio could be due to NAA concentration reductions or to Cr and/or Ch increases. However, because in studies about epilepsy in which absolute values were determined, the findings generally indicated NAA concentration reductions rather than Cr and/or Ch increases, it is likely that the demonstrated changes in the NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio are primarily due to a reduced NAA concentration. In either case, the finding of a reduced NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio reflects some impairment of the brain.

Third, the changes could be the result of changes in relaxation times. Although we cannot exclude this possibility, it is unlikely, because very different relaxation time changes would be necessary for NAA and for Cr or Ch to account for changes in the NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio.

Fourth, we did not perform segmentation of the MR imaging data, which would provide information on the amount of gray and white matter contributions to each voxel. Since metabolite concentrations are different in gray and white matter, the detected changes could therefore also be owing to differences in gray and white matter voxel composition between patients and control subjects. However, the visual selection of voxels in predominantly gray matter was performed with blinding to identification of patients and control subjects and to knowledge of the side of the seizure focus. It is therefore very unlikely that differences in gray and white matter voxel contributions are responsible for the detected changes. Nevertheless, correction for proportions of gray and white matter in voxels would probably enhance the results further.

In conclusion, findings at multisection MR spectroscopic imaging in patients with mesial TLE confirmed previous findings of reduced NAA concentration in ipsilateral hippocampal structures and simultaneously revealed reductions in the NAA/(Cr + Ch) ratio in widespread areas of the brain, and these findings suggested that repeated seizures that originate from the hippocampus lead to impairment of other brain regions. Contralateral structures were also affected. Therefore, the lateralization with spectral information from hippocampal areas alone could not be improved with the additional information. Further studies are underway to determine whether the analysis of all acquired voxels, because of greater statistical power, will provide an improved separation between the ipsilateral and contralateral sides in patients with mesial TLE.

Acknowledgments

K.D.L., G.B.M., and M.W.W. supported by National Institutes of Health grant ROI-NS31966. P.V. supported by DFG Forschungsstipendium VE 190/1-1.

Abbreviations

- Ch

choline-containing compounds

- Cr

creatine-phosphocreatine

- NAA

N-acetylaspartate

- TLE

temporal lobe epilepsy

References

- 1.Hugg JW, Laxer KD, Matson GB, Maudsley AA, Weiner MW. Neuron loss localizes human temporal lobe epilepsy by in vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging. Ann Neurol. 1993;34:788–794. doi: 10.1002/ana.410340606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ende GR, Laxer KD, Knowlton RC, et al. Temporal lobe epilepsy: bilateral hippocampal metabolite changes revealed at proton MR spectroscopic imaging. Radiology. 1997;202:809–817. doi: 10.1148/radiology.202.3.9051038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vermathen P, Ende G, Laxer KD, Knowlton RC, Matson GB, Weiner MW. Hippocampal N-acetylaspartate in neocortical epilepsy and mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:194–199. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matthews PM, Andermann F, Arnold DL. A proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study of focal epilepsy in humans. Neurology. 1990;40:985–989. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.6.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cendes F, Andermann F, Preul MC, Arnold DL. Lateralization of temporal lobe epilepsy based on regional metabolic abnormalities in proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic images. Ann Neurol. 1994;35:211–216. doi: 10.1002/ana.410350213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breiter SN, Arroyo S, Mathews VP, Lesser RP, Bryan RN, Barker PB. Proton MR spectroscopy in patients with seizure disorders. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15:373–384. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Connelly A, Jackson GD, Duncan JS, King MD, Gadian DG. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology. 1994;44:1411–1417. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.8.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gadian DG, Connelly A, Duncan JS, et al. 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy in the investigation of intractable epilepsy. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 1994;152:116–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1994.tb05202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng TC, Comair YG, Xue M, et al. Temporal lobe epilepsy: presurgical localization with proton chemical shift imaging. Radiology. 1994;193:465–472. doi: 10.1148/radiology.193.2.7972764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Margerison JH, Corsellis JA. Epilepsy and the temporal lobes: a clinical, electroencephalographic and neuropathological study of the brain in epilepsy, with particular reference to the temporal lobes. Brain. 1966;89:499–530. doi: 10.1093/brain/89.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marsh L, Morrell MJ, Shear PK, et al. Cortical and hippocampal volume deficits in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1997;38:576–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1997.tb01143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeCarli C, Hatta J, Fazilat S, Fazilat S, Gail-lard WD, Theodore WH. Extratemporal atrophy in patients with complex partial seizures of left temporal origin. Ann Neurol. 1998;43:41–45. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuzniecky R, Bilir E, Gilliam F, Faught E, Martin R, Hugg J. Quantitative MRI in temporal lobe epilepsy: evidence for fornix atrophy. Neurology. 1999;53:496–501. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.3.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sackellares JC, Siegel GJ, Abou-Khalil BW, et al. Differences between lateral and mesial temporal metabolism interictally in epilepsy of mesial temporal origin. Neurology. 1990;40:1420–1426. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.9.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henry TR, Mazziotta JC, Engel JJ. Interictal metabolic anatomy of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Arch Neurol. 1993;50:582–589. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540060022011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foldvary N, Lee N, Hanson MW, et al. Correlation of hippocampal neuronal density and FDG-PET in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1999;40:26–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb01984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubin E, Dhawan V, Moeller JR, et al. Cerebral metabolic topography in unilateral temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology. 1995;45:2212–2223. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.12.2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hammers A, Koepp MJ, Labbe C, et al. Neocortical abnormalities of [11C]-flumazenil PET in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology. 2001;56:897–906. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.7.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Grond J, Gerson JR, Laxer KD, Hugg JW, Matson GB, Weiner MW. Regional distribution of interictal 31P metabolic changes in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1998;39:527–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01416.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hugg JW, Kuzniecky RI, Gilliam FG, Morawetz RB, Faught RE, Hetherington HP. Normalization of contralateral metabolic function following temporal lobectomy demonstrated by 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging. Ann Neurol. 1996;40:236–239. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cendes F, Andermann F, Dubeau F, Matthews PM, Arnold DL. Normalization of neuronal metabolic dysfunction after surgery for temporal lobe epilepsy: evidence from proton MR spectroscopic imaging. Neurology. 1997;49:1525–1533. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.6.1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Serles W, Li LM, Antel SB, et al. Time course of postoperative recovery of N-acetyl-aspar-tate in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2001;42:190–197. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.01300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vermathen P, Ende G, Laxer KD, et al. Temporal lobectomy for epilepsy: recovery of the contralateral hippocampus measured by 1H MRS. Neurology. 2002;59:633–636. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.4.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Selva LM. Disturbances of learning and memory in temporal lobe epilepsy. In: Sack-ellares JC, Berent S, editors. Psychological disturbances in epilepsy. Butter-worth-Heinemann; Boston, Mass: 1996. pp. 109–120. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Engel JJ. Epileptogenesis. In: Engel JJ, editor. Seizures and epilepsy. Davis; Philadelphia, Pa: 1989. pp. 221–239. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li LM, Cendes F, Andermann F, Dubeau F, Arnold DL. Spatial extent of neuronal metabolic dysfunction measured by proton MR spectroscopic imaging in patients with localization-related epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2000;41:666–674. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Engel JJ. Introduction to temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 1996;26:141–150. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(96)00043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maudsley AA, Matson GB, Hugg JW, Weiner MW. Reduced phase encoding in spectroscopic imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1994;31:645–651. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910310610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vermathen P, Laxer KD, Matson GB, Weiner MW. Hippocampal structures: anteroposterior N-acetylaspartate differences in patients with epilepsy and control subjects as shown with proton MR spectroscopic imaging. Radiology. 2000;214:403–410. doi: 10.1148/radiology.214.2.r00fe43403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]