Abstract

The present study extended previous findings demonstrating self-criticism, assessed by the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (DAS; 1), as a potentially important prospective predictor of depressive symptomatology and psychosocial functional impairment over time. Using data from a prospective, 4-year study of a clinical sample, DAS self-criticism and neuroticism were associated with self-report depressive symptoms, interviewer-rated major depression, and global domains of psychosocial functional impairment four years later. Hierarchical multiple regression results indicated that self-criticism uniquely predicted depressive symptoms, major depression, and global psychosocial impairment 4 years later over and above the Time 1 assessments of these outcomes and neuroticism. In contrast, neuroticism was a unique predictor of self-report depressive symptoms only 4 years later. Path analyses were used to test a preliminary three-wave mediational model and demonstrated that negative perceptions of social support at three years mediated the relation between self-criticism and depression/global psychosocial impairment over four years.

Keywords: self-criticism, perfectionism, depression, psychosocial impairment, perceived social support

In recent years, self-criticism (SC), assessed by the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (DAS; 1), has emerged as a potentially important prospective predictor of depressive symptomatology and psychosocial functional impairment in clinical samples over time. For example, in a series of studies from the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program (TDCRP), pretreatment DAS SC significantly interfered with symptom reduction, the development of the therapeutic relationship, and the development of adaptive capacities in response to stressful life events at termination and follow-up 18 months after termination (2). Similarly, in analyses of data from the Collaborative Longitudinal Study of Personality Disorders (CLPS), Dunkley, Sanislow, Grilo, and McGlashan (3) found that DAS SC was related to negative social interactions, avoidant coping, perceived social support, and depressive symptoms three years later. These findings indicate that DAS SC reflects a pathological cognitive-personality trait that can be distinguished from a normal personality trait by virtue of its association with significant distress and psychosocial functional impairment over time, similar to personality disorders as conceptualized by the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; 4).

In considering DAS SC as a prospective predictor of depression and psychosocial impairment, it is important to distinguish DAS SC from the setting of high standards and goals for oneself (5,6). Contrary to the prevailing assumption that DAS SC primarily refers to high personal standards and motivation to attain perfection (7), DAS SC has been demonstrated to more closely reflect self-critical dimensions than personal standards dimensions of perfectionism. Specifically, factor analytic studies of several scales from different theoretical frameworks of perfectionism (8,9) have consistently identified two higher-order latent factors that are considered to reflect personal standards and self-criticism dimensions (6,10). DAS SC has been found to indicate the self-criticism factor, which reflects constant and harsh self-scrutiny, overly critical evaluations of one's own behaviour, and chronic concerns about others’ criticism (11). Dunkley and colleagues (6,12) noted the close similarity of the self-criticism factor of perfectionism to Blatt's (13,14) self-criticism construct, which encompasses these intrapersonal and interpersonal aspects of self-criticism.

Contrary to the widespread notion that SC individuals actively engage in perfectionistic strivings, it has been suggested that a defensive interpersonal orientation is the primary means through which SC individuals attempt to bolster and protect a vulnerable sense of self (15). For example, in relation to the five-factor model of personality (16), DAS SC and other SC measures have been related to neuroticism, introversion, and antagonism, and unrelated to conscientiousness, whereas personal standards measures are most closely associated with conscientiousness (5,15,17). In keeping with DAS SC (2), SC indicators have been found to have an adverse impact on employment status (18) and a wide range of relationships, including those with parents and friends (6,10,19-21). Finally, DAS SC and other SC measures have a stronger, more consistent relation with depressive symptoms than do measures that represent personal standards (5,7,11).

Although previous research suggests that DAS SC is a potentially important prospective predictor of depressive symptomatology and psychosocial functional impairment, more research is needed to assess and quantify this relation. First, given that studies have found DAS SC and other SC measures to be relatively stable over time (22,23), the association between SC and depressive symptomatology and psychosocial functional impairment should endure over several years. There have been several recent longitudinal studies demonstrating SC measures of perfectionism as prospective predictors of maladjustment outcomes, but these studies examined SC measures as prospective predictors of outcome over only periods of one year or less (24-29). Second, as theoretical writings have concentrated on perfectionism as a pervasive neurotic style (30-32), there is a need to demonstrate the unique contribution of SC over and above broader source traits, such as neuroticism, in predicting depression and psychosocial impairment over time (21,33,34). Several longitudinal studies have supported neuroticism as a predictor of depression (35,36). Further, Skodol et al. (37) found neuroticism to be related to several indices of functional impairment in previous CLPS analyses. Although Dunkley et al. (3) distinguished DAS SC from neuroticism in terms of unique relations with negative interpersonal characteristics and depressive symptomatology three years later, Enns et al. (25) found that the longitudinal effects of several other SC measures were nonsignificant once neuroticism was controlled for.

The primary purpose of the present study was to extend previous findings by examining DAS SC as a prospective predictor of self-report depressive symptoms and interviewer-rated major depression, specific domains of functioning (e.g., employment, relationships with parents, relationships with friends, recreation), and global domains of functioning (global satisfaction, global social adjustment, global assessment of functioning). We examined the predictive utility of SC over a substantially longer period of time (i.e., four years) than has previously been tested in the literature, which allowed for a compelling test of the stability of associations of SC with depressive symptomatology and psychosocial impairment over time. Further, we examined DAS SC as a predictor of negative change in depression and global functional impairment over four years by testing the relations between DAS SC and depression and global impairment four years later over and above the Time 1 levels of these variables and neuroticism.

Potential mediating mechanisms through which SC is related to depressive symptoms and psychosocial impairment over time also need to be examined (3). A secondary purpose of the present study was to examine whether the relation between SC and both depressive symptoms and global psychosocial functional impairment over time can be explained by SC individuals’ negative interpersonal characteristics (3,21,38). Dunkley et al. (3) proposed that SC is related to negative social interactions and negative perceptions of social support, which, in turn, predict depressive symptoms. First, individuals with higher levels of SC are concerned that others will be critical and rejecting as they are of themselves. This becomes expressed in a defensive interpersonal style that draws negative reactions from other people (3,21,39,40). Second, because SC individuals perceive that mistakes and shortcomings will result in rejection from others, these individuals perceive that others are unwilling or unavailable to help them in times of stress. In often perceiving that they have less social support available to them, individuals with higher levels of SC lack a critical resource that can make stressful situations seem less overwhelming and protect against the experience of depressive symptoms (12,41). Support for daily stress (or negative social interactions) and lower perceived social support as mediators of the relation between SC and depressive symptoms has been found in studies of nonclinical (12,26,27,42,43) and clinical samples (3,38).

A limitation of previous longitudinal studies testing mediational models in the literature is that the mediators have been assessed concurrently with maladjustment outcomes (3,26-29), which hinders the ability to make stronger causal statements from these findings. In a subset of the sample of the present study, we tested a preliminary, three-wave, mediational model of the relation between SC and depression/global psychosocial impairment four years later. To better test causal hypotheses, the present study examined SC, negative social interactions and perceived social support, and depression/global impairment at three successive time points that allowed considerable time to elapse between assessments, namely Time 1, Time 2 three years later, and Time 3 four years later, respectively (44). In sum, in addition to further demonstrating SC as an important prospective predictor of depression and psychosocial impairment, the present study sought to preliminarily highlight important mediating processes and contribute to identifying specific targets for clinical interventions across a wide range of clinical problems.

Method

Participants

Participants were 107 patients from a larger sample of 162 patients recruited for the New Haven site of the CLPS, a NIMH-funded, multiple-site, longitudinal, repeated-measures study of personality disorders (45). Participants participated voluntarily after a human investigation committee approved the study and informed consent was obtained. All participants were treatment seekers or treatment consumers from multiple clinical settings at entry to the CLPS. Recruitment of participants was targeted for patients meeting DSM-IV criteria for at least one of four personality disorders or major depressive disorder without personality disorder.

The present study initiated at the 24-month CLPS follow-up consisted of participants who completed the relevant personality measures at the 24-month CLPS follow-up (Time 1) and the depression and psychosocial functioning interview at both Time 1 and the 72-month CLPS follow-up four years later (Time 3). The final sample of 107 participants (42 men; 65 women) had a mean age of 34.44 years (SD = 8.19) at Time 1. The majority of participants were Caucasian (82%, n = 88), with 12% African American (n = 13), 5% Hispanic (n = 5), and 1% Asian (n = 1). The Hollingshead-Redlich socioeconomic status profile indicated a balanced distribution.

DSM-IV Axis I diagnoses were assessed at Time 1 using the Longitudinal Follow-Up Evaluation Adapted for Personality Study (LIFE-PS;46). Twenty-seven percent of the sample met current criteria for major depression, and an additional 9% met criteria for some other form of mood disorder (i.e., dysthymia, depressive disorder not otherwise specified) at Time 1. Forty percent of the sample met criteria for an anxiety disorder, 13% met criteria for an eating disorder, and 10% met criteria for a substance use disorder. Axis II diagnoses were assessed using the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (DIPD-IV;47), which has demonstrated acceptable interrater reliability (48). Fifty-three percent of the sample met criteria for one or more personality disorders, the most prevalent of which were avoidant personality disorder (35%), obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (23%), and borderline personality disorder (21%).

Procedure

At Time 1 (24-Month CLPS follow-up), participants completed a battery of questionnaires that included the DAS and revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R;16) and were interviewed by experienced raters with the LIFE-PS. At Time 3 four years later (72-Month CLPS follow-up), participants were again interviewed with the LIFE-PS and also completed a measure of depressive symptoms. A subset of seventy-five (29 men; 46 women) of these 107 participants also completed measures of negative social interactions and perceived social support at their 60-month CLPS follow-up (Time 2), which was three years after Time 1. This subsample was used to examine Time 2 negative social interactions and perceived social support as potential mediators to explain the relation between Time 1 SC and Time 3 depression/global psychosocial impairment four years later.

Measures

Self-Criticism

The 40-item DAS (1) Form A was used to assess SC. The DAS includes SC and need for approval scales, which were derived based on the factor analytic results of Imber et al. (49), who found that 15 items (e.g., “If I fail at my work, then I am a failure as a person”) loaded substantially on SC and 11 items (e.g., “If others dislike you, you cannot be happy”) loaded substantially on need for approval. Consistent with Imber et al. (49), the items with high loadings for each scale were summed in the present study, and the resulting composites had high internal consistency (α = .91 for perfectionism and α = .85 for need for approval). The two DAS scales were strongly correlated (r = .73), as they were in the NIMH TDCRP data (2). A residualized or “purified” version of the DAS SC was created using regression procedures to remove the overlapping, shared variance with need for approval, in keeping with previous studies (50). “Pure” SC correlated .68 with its original scale. Although the purified version of DAS SC is similar to the original DAS SC in terms of relations to defensive interpersonal traits, purified DAS SC has a significantly weaker relation with nonspecific affective vulnerability, namely neuroticism (5,17).

Neuroticism

Neuroticism was assessed using the NEO-PI-R (16), a self-report questionnaire designed to provide a comprehensive assessment of the five-factor model of personality. The neuroticism domain scale is defined by six eight-item facet scales. Costa and McCrae (16) reported extensive evidence supporting the internal consistency and validity of the neuroticism scale, as well as temporal stability over periods spanning several years.

Depressive Symptoms

The 24-item depression scale from the Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI;51) was used to assess the severity of current depressive symptoms at Time 3. The reliability and validity of the PAI depression scale has been supported across a variety of samples (51 scale was .93 in the present study.

Major Depression

Major depression scores were rated by the interviewers using the LIFE-PS Psychiatric Status Ratings (46). Psychiatric Status Ratings (PSR) ranged from 1 (no symptoms present) to 6 (with 5 representing presence of major depression and 6 representing presence of severe major depression). The LIFE has demonstrated reliability for assessing the longitudinal course of Major Depressive Disorder (52).

Psychosocial Functioning

Psychosocial functioning was assessed by the interviewers using the LIFE-PS. The LIFE includes questions to assess functioning in employment; household duties; student work; interpersonal relationships with parents, siblings, spouse/mate, children, other relatives, and friends; and recreation. The LIFE-PS also includes questions to derive three ratings of global functioning: global satisfaction, global social adjustment, and the DSM-IV Axis V Global Assessment of Functioning scale (GAFS). Most areas of functioning are rated on five-point scales of severity from 1 (no impairment, high level of functioning or very good functioning) to 5 (severe impairment or very poor functioning). The GAFS is rated on a 100-point scale, with 100 indicating the highest possible level of functioning. Support for the reliability of the LIFE psychosocial functioning scales has been demonstrated (53). Time 1 and Time 3 ratings were made for each patient's typical functioning for Month 24 and Month 72, respectively, of their CLPS follow-ups.

Negative Social Interactions

A revised 24-item version of the Test of Negative Social Exchange (TENSE; 54,55) was used to measure negative social interactions at Time 2 three years later. Participants rated how often they had experienced different types of negative interactions over the past month on a 10-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 9 (frequently). Items on the TENSE are designed to measure anger (e.g., “lost his or her temper with me”), insensitivity (e.g., “took my feelings lightly”), and interference (“tried to get me to do something that I did not want to do”). Reliability and validity evidence for the TENSE has been reported (54,55 scale was .96.

Perceived Social Support

Three four-item scales from the Social Provisions Scale (SPS;56) were summed to represent perceived available social support at Time 2 three years later. The SPS is a 24-item measure designed to assess the extent to which participants feel that each of six provisions of social relationships is currently available to them. We used the reliable alliance, attachment, and guidance scales to represent perceived social support, as did Dunkley et al. (3,12,42). The selected SPS scales have demonstrated moderate internal consistencies and construct validity (42,56). In the present study, the α coefficients were .77 for reliable alliance, .78 for attachment, .65 for guidance, and .84 for the total perceived social support score.

Model Testing

Path model testing was performed using Analysis of Momentary Structure 5.0 (AMOS Version 5.0;57), which uses the maximum likelihood (ML) estimation method to examine the fit of models to their observed variance-covariance matrices. Consistent with Hoyle and Panter's (58) recommendations, we considered multiple indexes of fit that provided different information for evaluating model fit (i.e., absolute fit, incremental fit relative to a null model, fit adjusted for model parsimony). That is, we considered the ratio of the chi-square value to the degrees of freedom in the model (absolute fit), with ratios in the range of 2 to 1 suggesting better fitting models (59). We also considered the goodness-of-fit index (GFI;60; absolute fit), incremental-fit index (IFI;61; incremental fit) and the comparative-fit index (CFI;62; incremental fit), with values .90 or over indicating better fitting models (58). Finally, we considered the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA;63; parsimony-adjusted fit), with values of .08 or less indicating adequate fit (64).

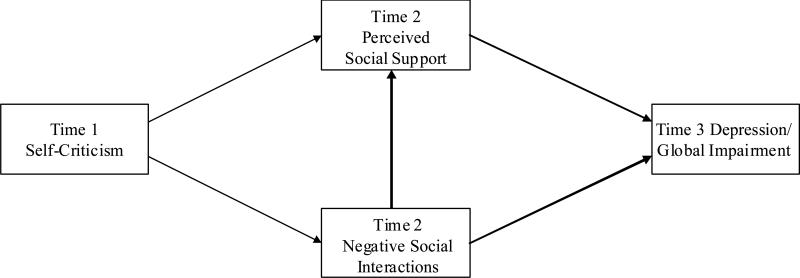

Figure 1 depicts the hypothesized relations based on the previous theoretical discussion and the final structural model of Dunkley et al. (3) for the mediation of the relation between SC and subsequent depression/global impairment: (1) Time 1 SC will predict negative social interactions and low perceived social support at Time 2 three years later; and (2) Time 2 negative social interactions and perceived social support will predict depression/global functional impairment one year later at Time 3. In addition, we also tested the hypothesis that high levels of negative social interactions contribute to lower perceptions of social support (65). Finally, an exploratory aspect of the modeling was to examine the relative predictive validity of Time 1 DAS SC controlling for the effects of Time 1 depression/global impairment and neuroticism. Thus, Time 1 depression/global impairment and neuroticism were included in the model and tested as relative predictors of Time 2 negative social interactions and perceived social support, and Time 3 depression/global impairment. The Time 1 depression/global impairment and neuroticism variables and their combined six tested paths are not shown in Figure 1 in order to distinguish these exploratory tests from the hypothesized relations based on theory and previous findings (3).

Figure 1.

Hypothesized structural model relating Time 1 self-criticism, Time 2 negative social interactions and perceived social support, and Time 3 depression/global impairment.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Means and standard deviations of the depression and psychosocial functioning ratings at Time 1 and Time 3 four years later are presented in Table 1. The present study examined ratings of specific functioning in five domains: employment, relationships with parents, relationships with friends, recreation, and household duties. Other LIFE ratings of specific domains were not examined because they applied to fewer than 50% of the sample (student work, relationships with spouse/mate and children) or were not of theoretical interest (relationships with siblings and other relatives). Comparing changes in ratings from Time 1 to Time 3, the results indicated significant improvements in PSR major depression, functioning in relationships with parents, functioning in household activities, and global functioning from Time 1 to Time 3.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Depression and Psychosocial Functioning Measures Assessed at Time 1 and Time 3 Four Years Later

| Time 1 | Time 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | M | SD | M | SD | F |

| Depression | |||||

| PAI Depressive Symptomsa | -- | -- | 23.03 | 13.80 | -- |

| LIFE PSR Major Depression | 2.55 | 1.78 | 2.09 | 1.63 | 5.48* |

| Specific Functional Impairment | |||||

| Employmentb | 2.05 | 1.30 | 1.91 | 1.07 | .11 |

| Relationships with Friends | 2.36 | 1.22 | 2.38 | 1.17 | .05 |

| Relationships with Parentsc | 2.38 | 1.15 | 2.14 | 1.02 | 4.04* |

| Recreation | 2.27 | 1.38 | 2.51 | 1.13 | 3.81 |

| Household Dutiesd | 2.65 | 1.22 | 2.19 | 1.05 | 15.48*** |

| Global Functional Impairment | |||||

| Global Satisfaction | 2.68 | 1.11 | 2.48 | 1.14 | 2.43 |

| Global Social Adjustment | 3.19 | 1.13 | 3.02 | 1.13 | 2.07 |

| Global Assess. of Functioning | 57.86 | 14.13 | 64.10 | 13.77 | 22.90*** |

Note. Assess. = Assessment.

N = 107 except where indicated.

n = 99 for Time 3.

n = 78 for Time 1 and n = 76 for Time 3.

n = 98 for Time 1 and Time 3.

n = 103 for Time 1 and n = 106 for Time 3.

As the present study's sample of 107 participants was a subset of the 162 participants originally recruited for the larger CLPS study, T tests comparing the means on all nine psychosocial functioning measures (major depression, five specific functioning, three global functioning) administered at CLPS baseline (24 months prior to Time 1 of the present study) suggested that the subsample of 107 participants in the present study generally did not differ from the other 55 participants of the original sample. Specifically, there was only one significant (p < .05) difference (global social adjustment) out of 9 comparisons. Further, as the mediation analyses are based on a subset of 75 participants from the 107 participants in the present study, T tests comparing the means of all 9 measures administered at Time 1 (24 months after CLPS baseline) suggested that the 75 participants who completed the Time 2 mediator measures generally did not differ from the 32 participants who did not complete the Time 2 mediator measures. Specifically, there was only one significant (p < .05) difference (recreation functioning) out of 9 comparisons.

Zero-order Correlations

Table 2 shows the zero-order correlations of Time 1 SC and neuroticism with PAI depressive symptoms, LIFE PSR major depression ratings, LIFE specific psychosocial impairment domains, and LIFE global psychosocial impairment domains at Time 1 and Time 3 four years later. Dunkley et al. (3) reported the correlations of SC and neuroticism with Time 1 LIFE major depression using a sample that included many of the participants of the present study but was not limited to these participants. The correlations of SC and neuroticism with Time 1 LIFE major depression reported here are based only on the participants of the present study. The LIFE PSR major depression rating and three global psychosocial impairment (satisfaction, social adjustment, assessment of functioning) ratings were strongly intercorrelated at both Time 1 and Time 3, with the magnitude of correlations ranging from .47 to .85. Subsequently, these four ratings were summed in order to obtain a reliable overall composite measure of depression/global psychosocial impairment. The internal consistency of this depression/global impairment composite was .86 and .87 at Time 1 and Time 3, respectively.

Table 2.

Zero-Order Correlations between Time 1 Self-Criticism, Time 1 Neuroticism, and Depression and Psychosocial Impairment at Time 1 and Time 3 Four Years Later

| Self-Criticism | Neuroticism | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Time 1 | Time 3 | Time 1 | Time 3 |

| Depression | ||||

| PAI Depressive Symptomsa | -- | .36*** | -- | .48*** |

| LIFE PSR Major Depression | .16 | .24* | .38*** | .19 |

| Specific Functional Impairment | ||||

| Employmentb | .17 | .01 | .45*** | .08 |

| Relationships with Friends | .18 | .14 | .37*** | .03 |

| Relationships with Parentsc | .09 | .03 | .17 | .11 |

| Recreation | .18 | .16 | .37*** | .11 |

| Household Dutiesd | .26** | .27** | .36*** | .40*** |

| Global Functional Impairment | ||||

| Global Satisfaction | .11 | .24* | .54*** | .12 |

| Global Social Adjustment | .23* | .27** | .47*** | .25* |

| Global Assessment of Functioning | −.18 | −.27** | −.57*** | −.30** |

| Depression/Global Impairment | .20* | .30** | .59*** | .25** |

Note. N =107 except where otherwise indicated.

Not administered at Time 1 and n = 99 for Time 3.

n = 78 for Time 1 and n = 76 for Time 3.

n = 98 for Time 1 and Time 3.

n = 103 for Time 1 and n = 106 for Time 3.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

In relation to depression, although Time 1 SC was unrelated to Time 1 LIFE major depression, SC was significantly related to Time 3 PAI depressive symptoms and Time 3 LIFE major depression four years later. On the other hand, Time 1 neuroticism was significantly related to Time 3 PAI depressive symptoms four years later and was related to Time 1 LIFE major depression, but was not significantly related to Time 3 LIFE major depression.

In relation to specific functional impairment ratings, Time 1 SC was unrelated to impairment in employment, relationships with parents, relationships with friends, and recreation. On the other hand, Time 1 neuroticism was significantly related to functional impairment in employment, relationships with parents, relationships with friends, and recreation at Time 1, but neuroticism was no longer related to these specific psychosocial impairment indices four years later. Both Time 1 SC and neuroticism were significantly related to impairment in household duties at both Time 1 and Time 3 four years later.

Finally, in relation to global psychosocial impairment ratings, Time 1 SC was significantly related to Time 1 impairment in global social adjustment and the depression/global impairment composite, but was not related to impairment in global satisfaction and global assessment of functioning at Time 1. However, Time 1 SC was related to all four indices of global functional impairment four years later. On the other hand, Time 1 neuroticism was strongly related to all four indices of global functional impairment at Time 1, but these relations were relatively weaker or nonsignificant four years later.

Hierarchical Multiple Regressions Analyses

A series of hierarchical multiple regression analyses addressed the question of whether Time 1 SC could predict unique variance in the depression and global psychosocial impairment measures at Time 3 four years later over and above the variance predicted by the Time 1 assessments of these outcomes and neuroticism. Six analyses predicted Time 3 PAI depressive symptoms, LIFE major depression, global satisfaction, global social adjustment, global assessment of functioning, and the depression/global impairment composite with the Time 1 assessment of these outcomes entered in the first block, Time 1 neuroticism entered in the second block, and Time 1 SC entered in the third block. Because PAI depressive symptoms were not assessed at Time 1, the Time 1 LIFE PSR major depression rating was controlled for in predicting Time 3 PAI depressive symptoms.

As shown in Table 3, Time 1 LIFE major depression accounted for significant amounts of variance in predicting Time 3 PAI depressive symptoms (10%) and LIFE major depression (9%) four years later. The Time 1 assessments of global satisfaction, global social adjustment, global assessment of functioning, and the depression/global impairment composite accounted for significant amounts of variance in Time 3 global satisfaction (7%), global social adjustment (19%), global assessment of functioning (28%), and depression/global impairment (20%), respectively, four years later. The subsequent entry of Time 1 neuroticism in the second block predicted incremental variance in Time 3 PAI depressive symptoms (15%), but neuroticism was not a unique predictor of Time 3 LIFE major depression and the global psychosocial impairment indices 4 years later when the Time 1 assessment of these outcomes was controlled for. In contrast, Time 1 SC entered in the third block predicted significant (p < .05) incremental variance in Time 3 PAI depressive symptoms (5%), LIFE major depression (3%), global satisfaction (5%), global social adjustment (3%, p < .06), global assessment of functioning (3%), and depression/global impairment (5%) 4 years later over and above the Time 1 assessments of these outcomes and neuroticism. Thus, SC predicted negative change in depression and global psychosocial impairment over four years.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analyses Examining Self-Criticism as a Predictor of Depressive Symptoms, Major Depression, Global Satisfaction, Global Social Adjustment, Global Assessment of Functioning, and Depression/Global Impairment at Time 3 Four Years Later

| T3 PAI Depressive Symptomsb | T3 LIFE Major Depression | T3 Global Satisfaction | T3 Global Social Adjustment | T3 Global Assessment of Functioning | T3 Depression/Global Impairment | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | β | ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 |

| Step 1 | .10** | .09** | .07** | .19*** | .28*** | .20*** | ||||||

| T1 Assessment | .31** | .30** | .27** | .43*** | .53*** | .45*** | ||||||

| Step 2 | .15*** | .01 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | ||||||

| T1 Neuroticism | .43*** | .09 | −.04 | .06 | .01 | −.02 | ||||||

| Step 3 | .05* | .03* | .05* | .03a | .03* | .05* | ||||||

| T1 Self-Criticism | .23* | .19* | .23* | .17a | −.19* | .23* | ||||||

Note. T1 = Time 1. T3 = Time 3. T1 Assessment connotes the Time 1 assessment of the respective outcome.

Time 1 LIFE PSR major depression ratings were entered in Step 1.

N = 107.

p < .06

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Mediational Model

A path analysis was conducted on the subsample (n = 75) of participants who completed the Time 2 measures of negative social interactions and perceived social support three years later to examine these variables as potential mediators of the incremental relation between Time 1 SC and the Time 3 depression/global impairment composite four years later. A skewed distribution was found for negative social interactions and perceived social support. Square root transformations were applied to these scores to better approximate a normal distribution for the analyses involving these variables. Dunkley et al. (3,17) reported the relations between SC and neuroticism, SC and negative social interactions, and SC and perceived social support using samples that included many of the participants of the present study but was not limited to these participants. The relations among these variables reported here are based only on the participants of the present study. Hierarchical regression analyses conducted on these 75 participants confirmed that Time 1 SC predicted significant (p < .05) amounts of incremental variance in Time 3 PAI depressive symptoms, LIFE major depression, global satisfaction, global social adjustment (p < .053), and depression/global impairment, but not global assessment of functioning, four years later. Thus, because SC exhibited incremental predictive validity in this subsample, the subsample was appropriate to examine mediational hypotheses to explain the incremental predictive relation between SC and Time 3 depression and global functional impairment indices four years later.

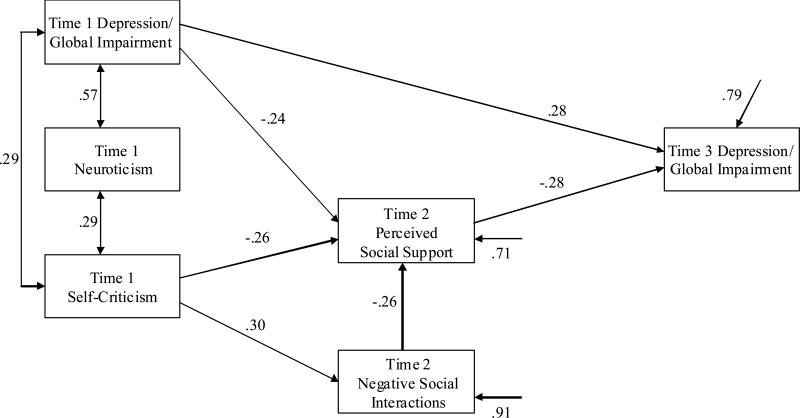

When estimating the hypothesized model shown in Figure 1, we also included Time 1 depression/global impairment and neuroticism as covariates of SC and controlled for their effects on the Time 2 mediators and Time 3 depression/global impairment. This model was estimated and resulted in an acceptable fit according to four out of five indices, χ2 (1, N = 75) = 2.51, ns; χ2 / df = 2.51; GFI = .99; IFI = .98; CFI = .98, with only RMSEA = .14, 90% C.I. (.00, .38), being lower than desirable. Next, as recommended in accordance with the parsimony principle (66), paths that did not contribute significantly to the model on the basis of Wald tests were removed one at a time, and the model was re-estimated each time. The nonsignificant paths from Time 1 depression/global impairment to negative social interactions, negative social interactions to Time 3 depression/global impairment, neuroticism to Time 3 depression/global impairment, neuroticism to perceived social support, and neuroticism to negative social interactions were deleted one at a time. The final model was acceptable according to all five fit indices: χ2 (6, N = 75) = 6.68, ns; χ2 / df = 1.11; GFI = .97; IFI = .99; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .04, 90% C.I. (.00, .16).

To test whether the relation between Time 1 SC and Time 3 depression/global impairment was fully mediated, this fully mediated model was compared to a partially mediated model, which included a path from SC to Time 3 depression/global impairment (67). The partially mediated model was not a significantly better fit to the data than the fully mediated model, χ2diff (1, N = 75) = 2.39, ns, and the path from SC to Time 3 depression/global impairment, β = .18, ns, was not significant. Thus, the relation between Time 1 SC and the Time 3 depression/global impairment composite was considered fully mediated.

Figure 2 presents the paths and significant standardized parameter estimates of the final structural model. The residual arrows indicate the proportion of variance in each variable unaccounted for by other variables in the model. Time 1 depression/global impairment had a direct link to Time 3 depression/global impairment. The relation between SC and Time 3 depression/global impairment was fully mediated or explained by shared variance with Time 1 depression/global impairment, Time 2 low perceived social support, and Time 2 negative social interactions, with the latter related to Time 3 depression/global impairment indirectly through low perceived social support. The relation between Time 1 SC and Time 2 perceived social support was partially explained through shared variance with Time 1 depression/global impairment. Perceived social support, in turn, was directly related to Time 3 depression/global impairment.

Figure 2.

Standardized parameter estimates of the final structural model relating Time 1 self-criticism, neuroticism, and depression/global impairment, Time 2 negative social interactions and perceived social support, and Time 3 depression/global impairment. The residual arrows denote the proportion of variance in the variable that was unaccounted for by other variables in the model.

As the above mediational analyses were conducted with the depression/global functional impairment composite as the outcome, we examined whether the mediational model would be supported when using Time 3 PAI depressive symptoms, LIFE PSR major depression, global satisfaction, and global social adjustment, respectively, as the outcome measure in the model controlling for the Time 1 assessments of these outcomes (LIFE PSR major depression was used as the Time 1 assessment for PAI depressive symptoms). Global assessment of functioning was not examined as an outcome because SC predicted a nonsignificant amount of incremental variance in this outcome in the subsample of 75 participants. In each of the four alternative models examined, the relation between Time 1 SC and the respective Time 3 outcome was fully mediated by Time 2 low perceived social support, or fully mediated/explained by Time 2 perceived social support and shared variance with the respective Time 1 outcome. In short, the fully mediated model was supported regardless of whether the depression/global impairment composite, PAI depressive symptoms, LIFE PSR major depression, global satisfaction, or global social adjustment was the Time 3 outcome.

Discussion

In interpreting the present findings, it is worth repeating that contrary to widespread assumption recent studies have shown that DAS SC more closely reflects the self-critical than the personal standards dimension of the broader perfectionism construct (5,6,11,17), which is primarily manifested in a defensive interpersonal orientation as opposed to active perfectionistic strivings (15). The present findings provided further support for self-criticism, assessed by the DAS, as a pathological cognitive-personality trait that is a prospective predictor of both depressive symptomatology and global psychosocial functional impairment over as long a period of time as four years, much like the conceptualization of DSM-IV personality disorders. In a preliminary way, the present findings also demonstrated important factors (e.g., lower perceived social support) that might mediate or explain why SC predicts negative change in depression and global psychosocial impairment over time.

DAS SC was related to both self-report depressive symptoms and interviewer-rated major depression and global domains of psychosocial functional impairment (e.g., global satisfaction, global social adjustment, global assessment of functioning) four years later. As the majority of findings in the perfectionism literature have been based on self-report measures, a novel aspect of the present study was the use of structured interviews to assess the distress and psychosocial functional impairment associated with SC. In addition, whereas Dunkley et al. (3) found SC to be related to self-reported depressive symptoms assessed three years later by the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI;68), we demonstrated the veracity of the relation between DAS SC and prospective depressive symptoms by using a different self-report measure of depressive symptoms, the PAI. These findings supported the predictive importance of SC over a substantially longer period of time (i.e., four years) than has previously been tested in the literature.

In addition to supporting an association between SC and depressive symptomatology and psychosocial impairment over time, an important contribution of our study was demonstrating that SC is neither equivalent nor reducible to concurrent levels of major depression, global psychosocial impairment, and/or neuroticism in adverse effects on subsequent major depression and global psychosocial impairment four years later (21,33). Specifically, SC predicted PAI depressive symptoms, major depression, global satisfaction, global social adjustment, global assessment of functioning, and the depression/global impairment composite (i.e., combination of LIFE major depression, global satisfaction, global social adjustment, and global assessment of functioning) four years later controlling for baseline assessments of these outcomes (LIFE major depression was controlled for in predicting Time 3 PAI depressive symptoms). This suggests that SC predicts negative change in depression and global psychosocial impairment over time, consistent with previous findings (2).

Further, some reviewers have suggested the need to demonstrate the unique predictive validity of specific traits (e.g., SC) over and above neuroticism (33). However, contrary to previous findings (35,36), we found that the association between neuroticism and major depression and psychosocial impairment weakened considerably over four years and neuroticism failed to uniquely predict major depression and global functional impairment four years later. In contrast, SC demonstrated incremental predictive validity in significantly predicting the two measures of depressive symptomatology and four measures of global psychosocial functioning (global social adjustment was a trend) four years later over and above the Time 1 levels of these variables and neuroticism. Thus, whereas previous work (25) found that neuroticism accounted for the longitudinal effects of various other SC measures, these findings are in keeping with previous findings distinguishing DAS SC from neuroticism in terms of unique prospective relations to depressive symptomatology and interpersonal characteristics (3).

In order to better understand the incremental predictive validity of SC, we performed a preliminary test of a three-wave mediational model with SC at Time 1, negative social interactions and perceived social support at Time 2 three years later, and depression/global impairment at Time 3 four years later. The three-wave design allowed a stronger test of causal hypotheses relative to previous longitudinal studies of mediational models that assessed the mediators concurrently with the maladjustment outcomes (3,26-29). The relation between Time 1 SC and Time 3 depression/global impairment was explained by Time 2 lower perceived social support and Time 2 negative social interactions, with the latter related to Time 3 depression/global impairment indirectly through lower perceived social support. Although the outcome in the main mediational analysis was the depression/global impairment composite, it is important to note that this fully mediated model applied to explaining the unique relation between SC and the individual indicators of depression (i.e., depressive symptoms, major depression) and global psychosocial impairment (i.e., global satisfaction, global social adjustment) as outcomes. These findings suggest that the relation between SC and depressive symptoms is explained by the tendency of these individuals to experience higher levels of daily stress and to negatively appraise the availability of social resources, consistent with previous findings (3,12,26,27,38,42,43). Our results strengthen the causal status of self-criticism in that it further identifies potential mechanisms of action through which self-criticism prospectively leads to depression/global impairment. In addition, Time 1 SC was related in part to Time 3 depression/global adjustment through shared variance with Time 1 depression/global impairment, which indicates stability in addition to negative change in the association between SC and depression/global impairment over time.

Although Time 2 negative social interactions was indirectly related to the depression/global impairment composite through lower perceived social support, negative social interactions was not directly related to the Time 3 depression/global impairment composite one year later. This finding is inconsistent with Dunkley et al. (3) finding negative social interactions to be a unique mediator in the relation between SC and depressive symptoms. This discrepant finding might be explained by the fact negative social interactions and depressive symptoms were assessed concurrently in Dunkley et al. (3), and it is possible that negative social interactions might not be a unique prospective predictor of maladjustment outcomes over time. On the other hand, this discrepant finding might be explained by the fact that Dunkley et al. (3) assessed depressive symptoms using the BDI, whereas the present study used different operationalizations of depressive symptomatology (PAI depressive symptoms, LIFE major depression) and global psychosocial impairment outcomes. Future research should examine negative social interactions as a mediator between SC and other outcome assessments over time.

Although SC was related to depressive symptomatology and global domains of psychosocial impairment over four years, it is noteworthy that SC was not significantly related to specific domains of psychosocial functional impairment (i.e., employment, relationships with parents, relationships with friends, recreation). These findings run contrary to previous studies using different methodologies (e.g., self-report, observer ratings) that have robustly demonstrated SC to have a negative impact on employment status (18) and interpersonal relationships (19-21). One possible explanation for why the relation between SC and specific functional impairment did not emerge in the present study is that the CLPS sample is largely comprised of patients with DSM-IV personality disorders (borderline, avoidant, schizotypal) that have been shown to have elevated levels of functional impairment in these specific employment and interpersonal domains (69,70). It might have been more difficult for SC to emerge as an important predictor of specific functional impairment in this sample of disturbed patients relative to a study of other clinical or nonclinical populations. Despite the absence of relation between SC and functional impairment in specific psychosocial domains, however, our findings demonstrated that individuals with higher levels of SC nevertheless exhibited lower perceptions of social support, which, in turn, explained their vulnerability to major depression and global psychosocial impairment over four years. These findings support the dysfunctional cognitive aspect of SC as playing a unique role in these individuals’ vulnerability to depression and global psychosocial impairment over time.

It is important to consider the clinical implications of our findings for intervention efforts, particularly given previous research showing DAS SC to be a predictor of negative outcome in treatment (2). Although previous experimental work has demonstrated success in manipulating personal standards aspects of perfectionism (71), it might prove more difficult to manipulate SC aspects of perfectionism. The broad implications for intervention of our results is that reducing SC perfectionists’ tendency to experience depression and global psychosocial impairment over time might be accomplished by decreasing negative social interactions and increasing their perceptions of social support availability. Components of an intervention to address these negative interpersonal characteristics associated with SC might include helping these individuals to reconceptualize relationships with critical and demanding others, modify negative biases in interpreting supportive behaviors, and improve social competence (42,72). The underlying premise in this intervention approach is that these cognitive and behavioural characteristics associated with SC are easier to modify than the personality trait itself (73,74) and could be appropriate targets in an intervention to treat SC individuals (12).

Although the interview methodology, the collection of repeated measures over four years, and three-wave mediational model in this study is an advance over previous studies relying on concurrent self-reports, there are some limitations and areas that warrant attention in future research. First, the self-report PAI depressive symptoms scale was not administered at Time 1. Thus, we were unable to examine the relations between Time 1 SC and Time 3 PAI depressive symptoms controlling for Time 1 PAI depressive symptoms. A strength, however, was controlling for Time 1 LIFE major depression and neuroticism in predicting Time 3 PAI depressive symptoms. These two variables combined to account for a substantial amount (25%) of variance in Time 3 PAI depressive symptoms scores that is a reasonable approximation to the amount of variance that Time 1 PAI depressive symptoms scores could be expected to account for in Time 3 PAI depressive symptoms scores four years later. Second, because these findings were largely based on the LIFE interview, it is important to validate these findings with other assessment modalities such as self-report. Third, because the mediational analyses were only conducted on a subset of 75 participants from the larger sample of 107 participants, these results need to be replicated. Fourth, although a strength of the mediational analyses was that there was considerable time elapsed between the three time points, an ideal test of mediation would assess for the cause (i.e., SC), mediators, and the effect at each of the three time points (44). Finally, we used a heterogeneous clinical sample that included a substantial portion of patients with DSM-IV personality disorder diagnoses but was not limited to patients with personality disorder diagnoses. Although DSM-IV personality disorders frequently co-occur with Axis I disorders in the more general clinical population, it is important to examine the generalizability of the present results to other patient populations (e.g., major depressive disorder patients) and nonclinical populations.

In summary, our study extended previous studies (2,3) by indicating that SC is a promising prospective predictor of both depressive symptomatology and global psychosocial functional impairment over four years over and above concurrent depression/global impairment and neuroticism. Our preliminary test of a three-wave meditational model allowed for stronger causal inferences than previous longitudinal research (3,12,26-29) in demonstrating that negative perceptions of social support mediate or explain the relation between SC and depression and psychosocial impairment over time.

Acknowledgements

David M. Dunkley, Department of Psychiatry; Charles A. Sanislow, Department of Psychiatry; Carlos M. Grilo, Department of Psychiatry; Thomas H. McGlashan, Department of Psychiatry.

Support for this work was provided by a fellowship from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and a Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec Bourse de Chercheurs-Boursiers (Dr. Dunkley), the Yale University site of the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study, and National Institutes of Health grants MH50850, MH073708, and MH001654.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Weissman AN, Beck AT. Development and validation of the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale: A preliminary investigation.. Paper presented at the 86th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association; Toronto, Ontario, Canada. 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blatt SJ, Zuroff DC. Empirical evaluation of the assumptions in identifying evidence based treatments in mental health. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25:459–486. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunkley DM, Sanislow CA, Grilo CM, McGlashan TH. Perfectionism and depressive symptoms three years later: Negative social interactions, avoidant coping, and perceived social support as mediators. Compr Psychiatry. 2006;47:106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Ed. 4. Author; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunkley DM, Kyparissis A. What is DAS Self-Critical Perfectionism Really Measuring? Relations with the Five-Factor Model of Personality and Depressive Symptoms. Pers Individ Dif. 2008;44:295–305. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunkley DM, Blankstein KR, Masheb RM, Grilo CM. Personal standards and evaluative concerns dimensions of “clinical” perfectionism: A reply to Shafran et al. (2002, 2003) and Hewitt et al. (2003). Behav Res Ther. 2006;44:63–84. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sherry SB, Hewitt PL, Flett GL, Harvey M. Perfectionism dimensions, perfectionistic attitudes, dependent attitudes, and depression in psychiatric patients and university students. J Couns Psychol. 2003;50:373–386. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frost RO, Marten PA, Lahart C, Rosenblate R. The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognit Ther Res. 1990;14:449–468. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hewitt PL, Flett GL. Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;60:456–470. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.60.3.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stoeber J, Otto K. Positive conceptions of perfectionism: Approaches, evidence, challenges. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2006;10:295–319. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1004_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Powers TA, Zuroff DC, Topciu RA. Covert and overt expressions of self-criticism and perfectionism and their relation to depression. Eur J Pers. 2004;18:61–72. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunkley DM, Zuroff DC, Blankstein KR. Self-critical perfectionism and daily affect: dispositional and situational influences on stress and coping. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84:234–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blatt SJ. Levels of object representation in anaclitic and introjective depression. Psychoanal Study Child. 1974;29:107–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blatt SJ. Experiences of depression: Theoretical, clinical, and research perspectives. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunkley DM, Blankstein KR, Zuroff DC, Lecce S, Hui D. Self-critical and personal standards factors of perfectionism located within the five-factor model of personality. Pers Individ Dif. 2006;40:409–420. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costa PT, McCrae RR. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) Professional Manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunkley DM, Sanislow CA, Grilo CM, McGlashan TH. Validity of DAS perfectionism and need for approval in relation to the five-factor model of personality. Pers Individ Dif. 2004;37:1391–1400. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zuroff DC, Koestner R, Powers TA. Self-criticism at age 12: A longitudinal study adjustment. Cognit Ther Res. 1994;18:367–385. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mongrain M. Parental representations and support-seeking behaviors related to dependency and self-criticism. J Pers. 1998;66:151–173. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mongrain M, Lubbers R, Struthers W. The power of love: Mediation of rejection in roommate relationships of dependents and self-critics. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2004;30:94–105. doi: 10.1177/0146167203258861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zuroff DC, Mongrain M, Santor DA. Conceptualizing and measuring personality vulnerability to depression: comment on Coyne and Whiffen (1995). Psychol Bull. 2004;130:489–511. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cox BJ, Enns MW. Relative stability of dimensions of perfectionism in depression. Can J Behav Sci. 2003;35:124–132. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zuroff DC, Blatt SJ, Sanislow CA, Bondi CM, Pilkonis PA. Vulnerability to depression: reexamining state dependence and relative stability. J Abnorm Psychol. 1999;108:76–89. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Enns M, Cox B. Perfectionism, stressful life events, and the 1-year outcome of depression. Cognit Ther Res. 2005;29:541–553. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Enns MW, Cox BJ, Clara IP. Perfectionism and neuroticism: A longitudinal study of specific vulnerability and diathesis-stress models. Cognit Ther Res. 2005;29:463–478. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Priel B, Besser A. Dependency and self-criticism among first-time mothers: The roles of global and specific support. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2000;19:437–450. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Priel B, Shahar G. Dependency, self-criticism, social context, and distress: Comparing moderating and mediating models. Pers Individ Diff. 2000;28:515–525. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rice KG, Leever BA, Christopher J, Porter JD. Perfectionism, stress, and social (dis)connection: A short-term study of hopelessness, depression, and academic adjustment among honors students. J Couns Psychol. 2006;53:524–534. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei M, Heppner PP, Russell DW, Young SK. Maladaptive perfectionism and ineffective coping as mediators between attachment and future depression: A prospective analysis. J Couns Psychol. 2006;53:67–79. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blatt SJ. The destructiveness of perfectionism: implications for the treatment of depression. Am Psychol. 1995;50:1003–1020. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.50.12.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamachek DE. Psychodynamics of normal and neurotic perfectionism. Psychology. 1978;15:27–33. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pacht AR. Reflections of perfection. Am Psychol. 1984;39:386–390. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coyne JC, Whiffen VE. Issues in personality as diathesis for depression: the case of sociotropy-dependency and autonomy-self-criticism. Psychol Bull. 1995;118:358–378. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.3.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Enns MW, Cox BJ. Personality dimensions and depression: Review and commentary. Can J Psychiatry. 1997;42:274–284. doi: 10.1177/070674379704200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hirschfield RM, Klerman GL, Lavori P, Keller MB, Griffith P, Coryell W. Premorbid personality assessments of first onset of major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:345–350. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810040051008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kendler KS, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Heath AC, Eaves LJ. A longitudinal twin study of personality and major depression in women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:853–862. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820230023002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skodol AE, Oldham JM, Bender DS, Dyck IR, Stout RL, Morey LC, et al. Dimensional representations of DSM-IV personality disorders: Relationships to functional impairment. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1919–1925. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shahar G, Blatt SJ, Zuroff DC, Krupnick JL, Sotsky SM. Perfectionism impedes social relations and response to brief treatment for depression. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2004;23:140–154. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flett GL, Hewitt PL, Garshowitz M, Martin TR. Personality, negative social interactions, and depressive symptoms. Can J Behav Sci. 1997;29:28–37. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frost RO, Trepanier KL, Brown EJ, Heimberg RG, Juster HR, Makris GS, Leung AW. Self-monitoring of mistakes among subjects high and low in perfectionistic concern over mistakes. Cognit Ther Res. 1997;21:209–222. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holahan CJ, Moos RH, Bonin L. Social support, coping, and psychosocial adjustment: a resources model. In: Pierce GR, Lakey B, Sarason IG, Sarason BR, editors. Sourcebook of Social Support and Personality. Plenum Press; New York: 1997. pp. 169–186. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dunkley DM, Blankstein KR, Halsall J, Williams M, Winkworth G. The relation between perfectionism and distress: hassles, coping, and perceived social support as mediators and moderators. J Couns Psychol. 2000;47:437–453. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sherry SB, Law A, Hewitt PL, Flett GL, Besser A. Social support as a mediator of the relationship between perfectionism and depression: A preliminary test of the social disconnection model. Pers Individ Diff. 2008;45:339–344. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Myths and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112:558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gunderson JG, Shea MT, Skodol AE, McGlashan TH, Morey LC, Stout RL, et al. The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: development, aims, design, and sample characteristics. J Personal Disord. 2000;14:300–315. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2000.14.4.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, Nielson E, Endicott J, McDonald-Scott P, Andreason NC. The Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:540–548. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180050009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Sickel AE, Yong L. The Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (DIPD-IV) McLean Hospital; Belmont, MA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zanarini MC, Skodol AE, Bender D, Dolan R, Sanislow CA, Schaefer E, et al. The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: reliability of Axis I and Axis II diagnoses. J Personal Disord. 2000;14:291–299. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2000.14.4.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Imber SD, Pilkonis PA, Sotsky SM, Elkin I, Watkins JT, Collins JF, et al. Mode-specific effects among three treatments for depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1990;58:352–359. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.3.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zuroff DC, Blatt SJ, Sotsky SM, Krupnick JL, Martin DJ, Sanislow CA, Simmens S. Relation of therapeutic alliance and perfectionism to outcome in brief outpatient treatment of depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:114–124. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morey LC. Personality Assessment Inventory – Professional Manual. Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.; Florida, USA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mueller TI, Leon AC, Keller MB, Solomon DA, Endicott J, Coryell W, Warshaw M, Maser JD. Recurrence after recovery from major depressive disorder during 15 years of observational follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1000–1006. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.7.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Warshaw MG, Keller MB, Stout RL. Reliability and validity of the Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation for assessing outcome of anxiety disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 1994;28:531–545. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)90043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ruehlman LS, Karoly P. With a little flak from my friends: Development and preliminary validation of the test of negative social exchange (TENSE). Psychol Assess. 1991;3:97–104. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Finch JF, Okun MA, Pool GJ, Ruehlman LS. A comparison of the influence of conflictual and supportive social interactions on psychological distress. J Pers. 1999;67:581–621. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cutrona CE, Russell D. The provisions of social relationships and adaptation to stress. In: Jones WH, Perlman D, editors. Advances in Personal Relationships. Vol. 1. JAI Press; Greenwich, CT: 1987. pp. 37–68. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Arbuckle JL. Amos users’ guide version 5.0. Small Waters Corporation; Chicago: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hoyle RH, Panter AT. Writing about structural equation models. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Structural Equation Modeling. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1995. pp. 158–176. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carmines E, McIver J. Analyzing models with unobserved variables: Analysis of covariance structures. In: Bohrnstedt G, Borgatta E, editors. Social Measurement: Current Issues. Sage; Beverly Hills, CA: 1981. pp. 65–115. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. LISREL-VI User's Guide. 3rd ed. Scientific Software; Mooresville, Indiana: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bollen KA. A new incremental fit index for general structural equation models. Sociol Methods Res. 1989;17:303–316. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bentler PM. Comparative fit indices in structural models. Psychol Bull. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Steiger JH. Structural model evaluation and modification: an interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behav Res. 1990;25:173–180. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing Structural Equation Models. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lakey B, Tardiff TA, Drew JB. Negative social interactions: assessment and relations to social support, cognition, and psychological distress. J Soc Clin Psychol. 1994;13:42–62. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Klein RB. Principles and Practices of Structural Equation Modeling. 2nd edition Guilford Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Holmbeck GW. Toward terminological, conceptual, and statistical clarity in the study of mediators and moderators: examples from the child-clinical and pediatric psychology literatures. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:599–610. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, Texas: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TH, Dyck IR, Stout RL, Bender DS, et al. Functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:276–283. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Skodol AE, Pagano ME, Bender DS, Shea MT, Gunderson JG, Yen S, et al. Stability of functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder over two years. Psychol Med. 2005;35:443–451. doi: 10.1017/s003329170400354x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shafran R, Lee M, Payne E, Fairburn CG. The impact of manipulating personal standards on eating attitudes and behaviour. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44:897–906. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brand EF, Lakey B, Berman S. A preventive, psychoeducational approach to increase perceived social support. Am J Community Psychol. 1995;23:117–135. doi: 10.1007/BF02506925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cantor N. From thought to behavior: “Having” and “doing” in the study of personality and cognition. Am Psychol. 1990;45:735–750. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Procidano ME, Smith WW. Assessing perceived social support: The importance of context. In: Pierce GR, Lakey B, Sarason IG, Sarason BR, editors. Sourcebook of Social Support and Personality. Plenum Press; New York: 1997. pp. 93–106. [Google Scholar]