Abstract

The infectivity of HIV-1 virions can be enhanced by inhibition of the proteasome in target cells, leading to the hypothesis that the proteasome degrades incoming virions as part of the intracellular antiviral defense. Here, several lines of evidence suggest instead that proteasome-inhibition renders target cells more susceptible to infection via an indirect effect on the cellular environment: 1) proteasome-inhibition increased infectivity more effectively when target cells were exposed to the inhibitors before exposure to virions, rather than when the inhibitors and virions were present simultaneously; 2) increased infectivity correlated directly with the duration of pre-exposure of cells to the inhibitors; 3) although increased infectivity was induced by as little as thirty minutes of pretreatment of target cells, binding of virions to target cells before the addition of inhibitor abolished the effect; and 4) increased infectivity persisted after removal of the inhibitors and the recovery of proteasome-activity within the target cells. Cell-cycle analyses revealed that an increased fraction of cells in G2/M may correlate with increased efficiency of infection. These data suggest that rather than relieving a target cell restriction based on the degradation of incoming virions, proteasome-inhibitors likely increase infectivity either via their effects on the cell-cycle or by increasing the expression of a host cell factor that facilitates infection.

Several studies have indicated that the inhibition of the proteasome during the exposure of target cells to virions increases the infectivity of HIV-1 (Schwartz, Marechal et al., 1998;Wei, Denton et al., 2005;Groschel & Bushman, 2005;Butler, Johnson et al., 2002). This effect was observed at the level of viral DNA accumulation in target cells; it was robust to pseudotyping with the envelope glycoprotein of vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV-G); and it was detected using either CD4-positive HeLa cells or various CD4-positive T cells lines as the targets of infection. The initial interpretation of these results focused on the hypothesis that the proteasome represents a host cell antiviral activity and that inhibitors relieve a host-cell restriction based on the degradation of incoming virions. However, two lines of evidence weigh against this interpretation: 1) HIV-1 infectivity shows no evidence of saturation of a host cell restriction factor at high concentrations of inocula (Day, Martinez et al., 2006); and 2) inhibition of the proteasome has little or no influence when target cells are arrested in G2/M, suggesting that the effect may be related to perturbation of progress through the cell cycle (Groschel & Bushman, 2005). To resolve the issue of whether inhibition of the proteasome enhances viral infectivity via a direct effect on incoming virions or via an indirect effect on the permissiveness of target cells, we undertook a series of experiments designed to characterize this effect with respect to the timing of exposure of target cells to the inhibitors and to virus, and to determine whether increased infectivity correlated with decreased proteasome-activity.

Results and Discussion

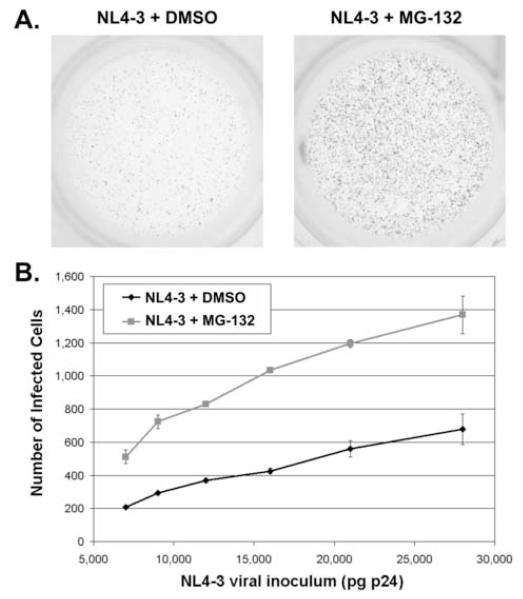

Simultaneous exposure of HeLa-CD4 cells (clone P4.R5) to HIV-1 virions and to the reversible peptide aldehyde proteasome-inhibitor MG-132 for five hours increased infectivity approximately 2.5 fold over a broad range of inocula [Figure 1, in which the virus is the molecular clone NL4-3 (Adachi, Gendelman et al., 1986)]. These results corroborated previous data (Butler, Johnson et al., 2002;Schwartz, Marechal et al., 1998;Wei, Denton et al., 2005;Santoni de Sio, Cascio et al., 2006).

Figure 1. Inhibition of the proteasome in target cells increases HIV-1 infectivity.

(A) P4.R5 indicator cells (CD4-positive HeLa cells containing an LTR-β-galactosidase sequence) were incubated with HIV-1 NL4-3 (2.8 ng) for 5 hours (with or without 25 μM MG-132) then washed and incubated at 37°C. Two days later the cells were stained with X-gal. Blue cells indicate infectious centers. (B) P4.R5 cells were incubated with varying amounts of HIV-1NL4-3 for 5 hours (with or without 25 μM MG-132). Two days later the cells were stained with X-gal and blue cells were counted. Each point represents the average of two measurements (error bars are the range of the data).

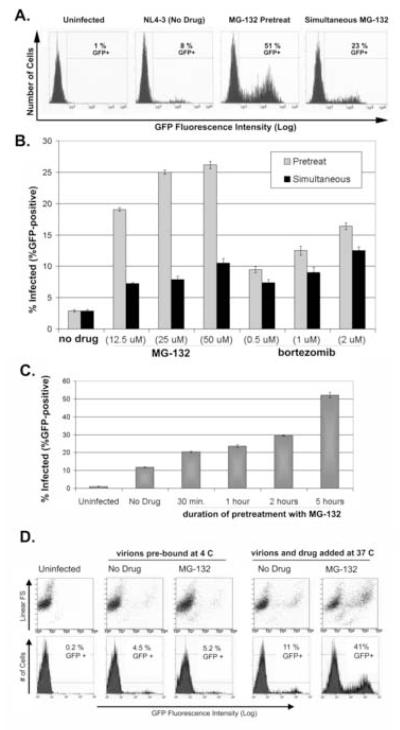

However, when the cells were pretreated with MG-132 for five hours, followed by removal of the inhibitor before exposure to virus, the increase in infectivity was even greater: approximately 6-fold with pretreatment of the cells compared to approximately 3-fold with simultaneous treatment (Figure 2A; experiments using an NL4-3 derivative containing a bicistronic GFP/Nef expression cassette at the 3′ end of the genome). The relatively greater effect of pretreatment was observed over a range of concentrations of MG-132 (Figure 2B). This effect was also observed using bortezomib, a boronic acid dipeptide that also binds and inhibits the proteasome reversibly (Zavrski, Jakob et al., 2005), although the relatively greater effect of pretreatment was less dramatic (Figure 2B). MG-132 forms relatively unstable adducts with the active sites of the β2 (trypsin-like) and β5 (chymotrypsin-like) catalytic subunits of the 20S proteasome; it also inhibits calpains and cathepsin B (Zavrski, Jakob et al., 2005). Bortezomib is a specific inhibitor of the chymotrypsin-like activity of the β5 subunit, and it forms more stable (but reversible) intermediates with the core of the 20S proteasome (Zavrski, Jakob et al., 2005). The relative effects of these compounds seen in Figure 2B may reflect these similar but not identical mechanisms of action.

Figure 2. Pretreatment of target cells with proteasome inhibitors yields maximal increases in infectivity, whereas treatment concurrent with a pulse of viral entry is ineffective.

(A) P4.R5 cells were either pretreated with MG-132 (25 μM) or not for 5 hours. Cells were then washed and exposed to HIV-1NL-EGFP (510 ng) for 5 hours either with (“Simultaneous”) or without (“Pretreat”) 25 μM MG-132. Cells were washed again and incubated at 37°C. Two days later, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for GFP fluorescence. (B) P4.R5 cells were either pretreated with the indicated concentrations of MG-132, bortezomib, or nothing for 5 hours. Cells were then washed and exposed to HIV-1NL-EGFP (300 ng) with the indicated concentrations of MG-132, bortezomib, or nothing for 5 hours. Cells were washed again and incubated at 37°C. Two days later, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for GFP fluorescence. Each point represents the average of two measurements (error bars are the range of the data). (C) P4.R5 cells were pretreated with 25 μM MG-132 for varying periods of time (30 minutes, 1 hour, 2 hours, or 5 hours). Cells were then washed and incubated with HIV-1NL-EGFP (510 ng) for 5 hours. Two days later, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for GFP fluorescence. Each point represents the average of two measurements (error bars are the range of the data). (D) P4.R5 cells were chilled to 4°C before the addition of HIV-1NL-EGFP (510 ng) and incubation at 4°C for 2 hours. Cells were then washed with cold media and incubated with 25 μM MG-132 or drug-free media at 37°C for 5 hours (“virions pre-bound at 4 C”). Cells were then washed and incubated at 37°C. Two days later, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for GFP fluorescence. As a control for the positive effect of MG-132 on infectivity, virions and MG-132 (25 μM) were added simultaneously to cells at 37° C for 5 hours, before washing, incubation at 37°C, and analysis by flow cytometry two days later (“virions and drug added at 37 C”). Numbers are the average percentage of GFP+ cells in duplicate infections. “FS”: forward scatter. The results are representative of two independent experiments.

Strikingly, infectivity was directly correlated with the duration of pretreatment of target cells with proteasome inhibitor; the effect was detectable after thirty minutes of pretreatment with MG-132 and increased with time for at least five hours (Figure 2C). These observations suggested the possibility that the inhibition of the proteasome might enhance infectivity by rendering target cells more permissive for infection, rather than by relieving a direct antiviral effect of the proteasome against incoming virions. Consistent with this hypothesis, the effect of MG-132 was essentially abolished if the target cells were exposed to virions at 4°C before warming to 37°C and adding MG-132 to allow synchronous viral entry and proteasomal inhibition (Figure 2D). Together, these results are most consistent with models in which inhibition of the proteasome either allows target cells to accumulate a specific factor that facilitates infection or induces their accumulation at a specific stage of the cell cycle that renders them more permissive.

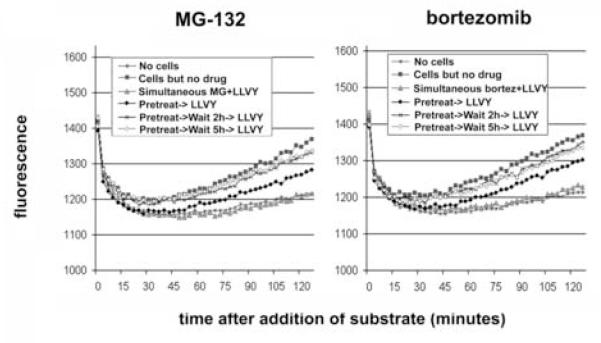

To rigorously test the hypothesis that proteasome inhibitors block degradation of incoming virions, we compared the kinetics of the recovery of proteasomal activity to the decay of infectivity after removal of these reversible inhibitors. Recovery of the proteasome was expected within one hour after withdrawal of MG-132 (Rock, Gramm et al., 1994), so that any virologic effect persisting after this time would not likely be due directly to inhibition of the proteasome. To confirm the expected kinetics of proteasomal recovery, the activity of the proteasome within target cells was measured using the substrate Suc-LLVY-AMC, which fluoresces when cleaved by the chymotryptic-like activity of the 20S proteasome (Stein, Melandri et al., 1996). In this live cell assay, proteasomal activity was detected within 15-30 minutes after the addition of substrate (Figure 3; compare “Cells but no drug” with “No cells”). Inclusion of proteasome-inhibitors during the assay reduced the signal to the level of the controls from which cells were omitted (compare “Simultaneous MG+LLVY” and “Simultaneous bortez+LLVY” with “No cells”). Pretreatment of cells for five hours followed by removal of the inhibitors just before the addition of substrate revealed recovery of activity by 45-60 minutes. A delay of two or five hours between pretreatment and the addition of substrate resulted in nearly complete recovery of proteosomal activity, which was almost indistinguishable from untreated cells.

Figure 3. Recovery of intracellular proteasome activity after removal of inhibitors.

Left panel: P4.R5 cells were pretreated with MG-132 (25 μM) or nothing for 5 hours. The cells were then washed and exposed to 150 μM Suc-LLVY-AMC (with or without 25 μM MG-132) immediately or after a 2- or 5-hour incubation. Right panel: P4.R5 cells were pretreated with bortezomib (1 μM) or nothing for 5 hours. The cells were then washed and exposed to 150 μM Suc-LLVY-AMC (with or without 1 μM bortezomib) immediately or after a 2- or 5-hour incubation. Measurements were taken every 3 minutes in a fluorometer; the cells were maintained at 37° C. Each point represents the average of 3 measurements (C.V. < 1% in all cases). “LLVY” is suc-LLVY-AMC.

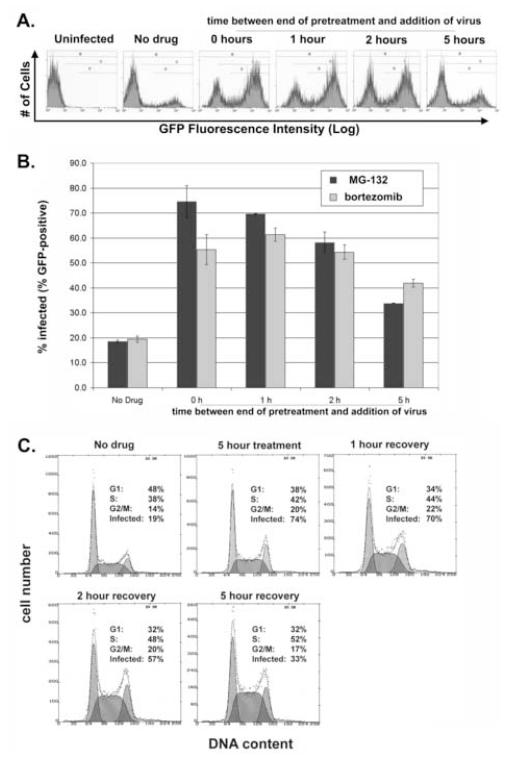

In contrast, pre-exposure of target cells to MG-132 or bortezomib for five hours induced a state of increased efficiency of infection that was almost undiminished two hours after removal of the inhibitors and was still detectable five hours after removal (Figure 4A and 4B). Together, the data of Figures 3, 4A and 4B suggested that the recovery of the proteasome markedly precedes reversion of the cellular state of increased permissiveness for infection; despite recovery of enzymatic activity within 45-60 minutes after removal of inhibitor and essentially complete recovery after two hours, a state of increased permissiveness for infection persisted in pretreated cells for at least five hours.

Figure 4. The cellular state of increased permissiveness for HIV-infection persists after removal of proteasome inhibitors; relationship to the cell-cycle.

(A) P4.R5 cells were either pretreated with MG-132 (25 μM) or not for 5 hours. Cells were then washed and incubated at 37°C for 0, 1, 2 or 5 hours. The cells were then exposed to HIV-1NL-EGFP (820 ng) for 8 hours, washed, and incubated at 37°C. Two days later, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for GFP fluorescence. (B) P4.R5 cells were either pretreated with MG-132 (25 μM), bortezomib (1 μM) or nothing for 5 hours. Cells were then washed and incubated at 37°C for 0, 1, 2 or 5 hours. The cells were then exposed to HIV-1NL-EGFP (820 ng) for 8 hours, washed, and incubated at 37°C. Two days later, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for GFP fluorescence. Each point represents the average of independent infections, one of which is shown in panel A for MG-132 (error bars are the range of the data). Gate “D” as shown in panel A was used to derive the data. (C) The cells treated with MG-132 and analyzed for infectivity in panel B were subjected to cell-cycle analysis by staining with propidium iodide to measure DNA content. These cell cycle analyses were performed on cells treated in duplicate; the average fraction of cells in G1, S, and G2/M are indicated within each representative histogram. The infectivity values are from the data of panel B.

The increased infectivity induced by inhibition of the proteasome appears to reflect a state of increased target cell permissiveness that persists for several hours after recovery of proteasomal activity. How might inhibition of the proteasome alter the cellular milieu to facilitate infectivity? Inhibition of the proteasome extends the half-life of many cellular proteins, with the most dramatic effects on normally short-lived proteins. Increased infectivity was detected within thirty minutes of pretreatment with proteasome-inhibitor (Figure 2C), suggesting that if this effect is due to an increase in the accumulation of a specific cellular protein, then this protein is likely to have a very short half-life. Notably, proteasome-inhibitors enhance the infectivity of HIV-1 virions that are pseudotyped with VSV-G (Schwartz, Marechal et al., 1998), suggesting that this effect is not likely related to increased expression of CD4 or co-receptors. Interestingly, although increased infectivity is detectable within thirty minutes of exposure of target cells to proteasome-inhibitors, the effect is not apparent when cells are exposed to inhibitor concurrent with a pulse of viral entry (Figure 2D). This observation suggests that an early and committed step is modulated; apparently, this step cannot be enhanced significantly even with the onset of the more permissive cellular state by thirty minutes after viral entry. Conceivably, viral entry itself could be the facilitated step; this mechanism provides an explanation for the increased levels of cytosolic p24 Gag detected in target cells treated with proteasome inhibitors without requiring degradation of incoming virions (Schwartz, Marechal et al., 1998). Core-uncoating or an intracellular transport step could also be facilitated.

An alternative to increased expression of a specific cell factor is alteration of the cell cycle. Cell cycle regulators are regulated by proteolysis mediated by the ubiquitinproteasome system (Peters, 1998;Gutierrez & Ronai, 2006). Consequently, inhibition of the proteasome has several effects on the cell cycle, including a block of G1/S and metaphase transitions and delayed progression through S phase (Machiels, Henfling et al., 1997). Notably, the permissiveness of cycling target cells to HIV-infection is enhanced in G2/M, and the enhancing effect of certain cell-cycle inhibitors on HIV infection and the effect of MG-132 are not additive, suggesting a common mechanism of action (Groschel & Bushman, 2005).

To test the cell-cycle hypothesis, we correlated the effect of proteasome inhibitors on the distribution of cells throughout the cell cycle with their effect on infectivity. After five hours of pretreatment with MG-132, the fraction of cells in S and G2/M was increased at the expense of the fraction in G1 (Figure 4C). After removal of the inhibitor, the fraction of cells in G1 decreased further over the next five hours, while the fraction of cells in S phase increased (Figure 4C); similar results were obtained with bortezomib (data not shown). These results excluded the fraction of cells in G1 or S as correlates of increased permissiveness for infection, since infectivity decreased after removal of MG-132 (Figure 4A and B). Interestingly, the fraction of cells in G2/M increased from 14 to 20% with pretreatment, then declined to an intermediate value of 17% five hours after removal of the inhibitor; these data are to an extent consistent with the effect on infectivity, which increased from 19 to 74% with pretreatment and declined to an intermediate value of 33% five hours after removal of the inhibitor. Although the absolute increase in infectivity caused by proteasome inhibitors in these experiments (300% or more in most cases) seems difficult to attribute to a 50% increase in the number of cells in G2/M, it remains conceivable that during the five hours of exposure to virus the total fraction of cells that have transited G2/M could be sufficiently increased by proteasome-inhibition to account for the infectivity effect.

The apparent inhibitory effect of the proteasome on infectivity could potentially underlie two phenomena in the virology of HIV-1: restriction by TRIM5α and the CD4-independent enhancement of infectivity by the accessory protein Nef. Old World monkey TRIM5α restricts HIV-1 at a post-entry step, and since some TRIM family proteins are involved in ubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation, it seemed plausible that the proteasome might mediate this effect (Stremlau, Owens et al., 2004). However, it appears that inhibition of the proteasome does not relieve restriction mediated by TRIM5α (Stremlau, Perron et al., 2006). In the case of Nef, the mechanism by which this protein enhances infectivity independently of CD4 has been obscure, but very recent data suggest that treatment of target cells with proteasome inhibitors equalizes the infectivity of Nef-positive and Nef-negative virions via a relatively greater effect in the absence of Nef (Qi & Aiken, 2006). This result was interpreted to suggest that Nef reduces the susceptibility of incoming virus particles to proteasomal degradation in target cells. In view of the findings herein, it seems more likely that proteasome inhibition would increase the expression of a cellular factor such that the effect of Nef on infectivity is rendered moot. However, we have not observed loss of the Nef-effect by proteasome inhibition; instead, we observed a similar relative increase in infectivity when either Nef-positive or Nef-negative virions were used over a wide range of inocula to infect target cells treated with MG-132 (data not shown).

In summary, we propose that the increased infectivity of HIV-1 to target cells treated with proteasome-inhibitors is not a consequence of relief of a direct antiviral activity of the proteasome. We cannot exclude an effect on the cell cycle, specifically arrest in G2/M, as the basis for the virologic effect of these inhibitors. Alternatively, the data are consistent with the hypothesis that inhibition of the proteasome leads to the accumulation of a cellular co-factor that facilitates a very early event during viral replication.

Materials and Methods

Cells

P4.R5 cells were obtained from Nathaniel Landau and maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (100 U/mL)-streptomycin (100 μg/mL) (pen/strep), 2 mM L-glutamine, and puromycin (1 μg/ml). HEK293T cells (also from Nathaniel Landau) were maintained in complete medium consisting of minimum essential medium (E-MEM) supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin /streptomycin, and L-glutamine.

Proteasome inhibitors, cell treatments, and substrate for intracellular proteasome activity assays

“InSolution™ MG-132”, a 10 mM solution of MG-132 (Z-LLL-CHO) in DMSO, was purchased from Calbiochem (#474791). Bortezomib (Velcade™; Millennium Pharmaceuticals) was provided by the pharmacy of the San Diego Veterans Affairs Healthcare System. After exposure to proteasome inhibitors, cells were washed 3 times with fresh media. Fluorogenic Proteasome Substrate III Suc-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-AMC (Suc-LLVY-AMC) was purchased from Axxora (#BST-S-280) and resuspended in DMSO.

Virus production

A plasmid encoding the complete proviral sequence of HIV-1 clone NL4-3 (pNL4-3) and a pNL4-3 derivative expressing GFP (pNL-EGFP) were used for the production of NL4-3 and NL-EGFP viral stocks. pNL-EGFP encodes enhanced green fluorescent protein 3′ of the env sequence, followed by an internal ribosomal entry site and the nef sequence, and the remainder of the 3′ long terminal repeat (LTR); this construct was originated by Naoki Yamamoto and provided by Celsa Spina. HEK293T cells were transiently transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), 20 μg of plasmid DNA, and 2 million cells plated in 100-mm-diameter tissue culture dishes. Virus-containing supernatants were collected 2 days later, centrifuged at low speed to pellet cells and cellular debris, filtered (pore size, 0.2 μm), and then frozen at -80°C. Prior to freezing, all virus-containing supernatants were sampled for quantification of the p24 capsid protein by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

P4.R5 infectious center assay

The P4.R5 cell line contains the ß-galactosidase indicator under the control of the HIV-1 LTR. Cells were plated at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well in a 48-well tissue culture plate. On the following day, cells were infected in duplicate with 100 μL of several dilutions of NL4-3 virus normalized by p24 capsid protein. After a 2 hour incubation at 37°C, the volume was increased to 500 μL by adding 400 μL of complete medium. After a 2-day incubation at 37°C, cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde-0.2% glutaraldehyde in PBS. After washing twice with PBS, cells were stained in an X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-ß-D-galactopyranoside) solution overnight and finally washed again with PBS. Infectivity was measured by counting the blue-stained, HIV-infected foci, using a digital imaging system and computer software as described (Day, Martinez et al., 2006).

Measurement of infectivity by flow cytometry

P4.R5 cells were plated at a density of 8 × 104 cells per well in a 12-well tissue culture plate. On the following day, cells were infected in duplicate with 0.5 mL of NL-EGFP virus normalized by content of p24 capsid protein. After a 5 or 8 hour incubation at 37°C the virus-containing media was aspirated and the cells were washed 3 times with fresh media. After washing, 2 mL of fresh media was added to each well. After a 2-day incubation at 37°C, cells were detached using trypsin-EDTA, pelleted by low-speed centrifugation, and fixed in 0.5 mL of 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Cells were then analyzed for GFP fluorescence using a flow cytometer.

Measurement of intracellular proteasome-activity using Suc-LLVY-AMC

P4.R5 cells were plated at a density of 3 × 104 cells per well in clear-bottom, black-walled 96-well tissue culture plates. Cells were incubated with 150 μL of 25 μM MG-132, 1 μM bortezomib, or drug-free media for 5 hours at 37°C. Cells were washed 3 times with 200 μL of fresh media and then replenished with 150 μL of fresh media. Cells were then incubated for 0, 2 or 5 hours at 37°C. Media was then aspirated and wells were loaded with 150 μL of 150 μM Suc-LLVY-AMC with or without simultaneous MG-132 (25 μM) or bortezomib (1 μM). Fluorescence masurements were obtained every 3 minutes using a Tecan-Genios fluorometer (excitation = 360 nm, emission = 465 nm, manual gain = 50); the cells were maintained at 37°C throughout the experiment.

Measurement of DNA content and cell-cycle determination by flow cytometry

P4.R5 cells were treated or not with MG-132 as described in the legend of Figure 4 before fixation with 70% ethanol overnight, then stained with propidium iodide (50 μg/ml) for 30 minutes in the presence of 10 μg/ml RNaseA in calcium- and magnesium-free PBS before analysis by flow cytometry. Histograms of cell number versus DNA-content were analyzed using MulticycleAV software (Phoenix Flow, San Diego) to derive estimates of the fraction of cells in G1, S, and G2/M phases of the cell cycle.

Acknowledgements

Megan Dueck was enrolled in the Molecular Pathology graduate program at UCSD. We thank Ned Landau for the HeLa-P4.R5 and HEK293T cells; Celsa Spina, Yoshio Inagaki, and Naoki Yamamoto for the pNL-GFP construct; John Day for technical advice; Judy Nordberg of the UCSD CFAR and SDVAHCS Flow Cytometry Core; and Sherri Rostami of the UCSD CFAR for the p24 assays. This work was supported by a grant from the NIH (AI30201), the Center for AIDS Research at UCSD (NIH AI36214), and the Research Center for AIDS and HIV Infection at the San Diego Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adachi A, Gendelman HE, Koenig S, Folks T, Willey R, Rabson A, Martin MA. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and non-human cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. Journal of Virology. 1986;59:284–291. doi: 10.1128/jvi.59.2.284-291.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler SL, Johnson EP, Bushman FD. Human immunodeficiency virus cDNA metabolism: notable stability of two-long terminal repeat circles. J.Virol. 2002;76:3739–3747. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.8.3739-3747.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day JR, Martinez LE, Sasik R, Hitchin DL, Dueck ME, Richman DD, Guatelli JC. A computer-based, image-analysis method to quantify HIV-1 infection in a single-cycle infectious center assay. J Virological Methods. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.06.019. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groschel B, Bushman F. Cell cycle arrest in G2/M promotes early steps of infection by human immunodeficiency virus. J.Virol. 2005;79:5695–5704. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5695-5704.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez GJ, Ronai Z. Ubiquitin and SUMO systems in the regulation of mitotic checkpoints. Trends Biochem.Sci. 2006;31:324–332. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machiels BM, Henfling ME, Gerards WL, Broers JL, Bloemendal H, Ramaekers FC, Schutte B. Detailed analysis of cell cycle kinetics upon proteasome inhibition. Cytometry. 1997;28:243–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JM. SCF and APC: the Yin and Yang of cell cycle regulated proteolysis. Curr.Opin.Cell Biol. 1998;10:759–768. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi M, Aiken C. Selective Restriction of Nef-Defective HIV-1 by a Proteasome-Dependent Mechanism. J.Virol. 2006 doi: 10.1128/JVI.02099-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock KL, Gramm C, Rothstein L, Clark K, Stein R, Dick L, Hwang D, Goldberg AL. Inhibitors of the proteasome block the degradation of most cell proteins and the generation of peptides presented on MHC class I molecules. Cell. 1994;78:761–771. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90462-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Sio F. R. Santoni, Cascio P, Zingale A, Gasparini M, Naldini L. Proteasome activity restricts lentiviral gene transfer into hematopoietic stem cells and is down-regulated by cytokines that enhance transduction. Blood. 2006;107:4257–4265. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz O, Marechal V, Friguet B, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Heard JM. Antiviral activity of the proteasome on incoming human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Journal of Virology. 1998;72:3845–3850. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3845-3850.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein RL, Melandri F, Dick L. Kinetic characterization of the chymotryptic activity of the 20S proteasome. Biochemistry. 1996;35:3899–3908. doi: 10.1021/bi952262x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stremlau M, Owens CM, Perron MJ, Kiessling M, Autissier P, Sodroski J. The cytoplasmic body component TRIM5alpha restricts HIV-1 infection in Old World monkeys. Nature. 2004;427:848–853. doi: 10.1038/nature02343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stremlau M, Perron M, Lee M, Li Y, Song B, Javanbakht H, az-Griffero F, Anderson DJ, Sundquist WI, Sodroski J. Specific recognition and accelerated uncoating of retroviral capsids by the TRIM5alpha restriction factor. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2006;103:5514–5519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509996103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei BL, Denton PW, O’Neill E, Luo T, Foster JL, Garcia JV. Inhibition of lysosome and proteasome function enhances human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J.Virol. 2005;79:5705–5712. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5705-5712.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavrski I, Jakob C, Schmid P, Krebbel H, Kaiser M, Fleissner C, Rosche M, Possinger K, Sezer O. Proteasome: an emerging target for cancer therapy. Anticancer Drugs. 2005;16:475–481. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200506000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]