Abstract

This paper provides an overview of the Multisite Violence Prevention Project, a 5-year project to compare the effects of a universal intervention (all students and teachers) and a targeted intervention (family program for high-risk children) on reducing aggression and violence among sixth graders. First, the paper describes the role of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in developing the project. Second, it details the background of researchers at the four participating universities (Duke University, The University of Georgia, University of Illinois at Chicago, and Virginia Commonwealth University) and examines the characteristics of the selected schools (n=37). Finally, the paper summarizes the theoretical perspectives guiding the work, the development of interventions based on promising strategies, the decision to intervene at the school level, the research questions guiding the project, the research design, and the measurement process for evaluating the results of the program.

Introduction

To increase knowledge of what works to prevent youth violence, the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (NCIPC), a component of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), provided funding to initiate a multiyear, multisite evaluation study. Through a competitive peer-review process, four universities were awarded funding to develop and implement the study. The overall goal was to determine the effectiveness of several interventions—both alone and in combination—designed to reduce aggressive and violent behavior among middle school–aged students.

This paper provides an overview of the Multisite Violence Prevention Project. The first section describes CDC's role in violence prevention and in the development of this project. The second section describes the researchers at the four participating universities and the characteristics of the selected schools. The final section provides an overview of the theoretical background of the project, the rationale for focusing on sixth graders, the theoretical and practical importance of comparing universal and targeted approaches, the research questions, expected effect at the school level, the study design, the interventions, and the measurement methods. Each of these topics is discussed in detail in other papers in this supplement.1–6

CDC's Role

CDC's NCIPC provides leadership, coordination, and expertise to facilitate the development, evaluation, and implementation of interventions to prevent injuries—including those produced by violence—or to reduce their incidence, severity, and adverse outcomes. NCIPC uses a science-based approach to understand and prevent violence. This approach involves four steps: (1) describing the problem, (2) identifying risk and protective factors, (3) developing and evaluating interventions and policies, and (4) assuring widespread implementation and dissemination of effective programs.

Many studies have addressed the prevalence of school violence and its characteristics and risk factors.7 Growing recognition of violence as a preventable health problem has increased the demand for effective prevention programs. However, rigorous evaluation of programs, particularly those for adolescents, has been relatively limited.

The dearth of evaluated programs for adolescents is of particular concern given the general agreement that the transition to middle school is a particularly crucial time to focus prevention efforts. This school transition occurs at the same time as important developmental events, including hormonal and physical changes, development of a broader social perspective, changes in the nature of male–female relationships, increasing concerns about approval from peers, and enhanced expectations for academic success.8 The frequency of violence and other problem behaviors such as drug use also tend to increase during middle school, particularly during sixth grade.9

Epidemiologic and developmental risk literature points to two important aspects of violence prevention that emerge during this age period: (1) the increased risk of the overall population resulting from group norms that tolerate and perhaps even support using aggression in response to interpersonal conflicts and other frustrations7 and (2) the emergence of serious delinquency and violence among a small number of youth—those commonly referred to as high-risk—who are responsible for a large proportion of adolescent violence.10 Similarly, two complementary strategies dominate school interventions for this age group: (1) those strategies focusing on the whole school to change school norms related to aggression and violence11,12 and (2) those strategies focusing on multimodal interventions for managing and altering the developmental trajectory of high-risk children.13–15 It is unknown whether one approach is more effective than the other in reducing violence or whether both approaches are necessary.

To address these gaps and to better understand what works to prevent youth violence in middle schools, NCIPC provided funding in the fall of 1999 to initiate a 5-year, multisite evaluation study. The decision to conduct the study using multiple sites was driven, in part, by the need to move from efficacy to effectiveness.4

Participating Researchers and Schools

The four participating universities—Duke University, The University of Georgia, University of Illinois at Chicago, and Virginia Commonwealth University—were selected on the basis of demonstrating the following criteria: (1) capacity to carry out a large-scale project, as evidenced by previous experience working with violence reduction programs involving family, student, and teacher interventions; (2) ability to cultivate and sustain positive, productive partnerships with schools and community groups; and (3) commitment to and experience with collaborative research. Researchers from each of the participating universities joined staff members of NCIPC in a partnership to plan and implement the study.

Duke University

Investigators at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, bring a long history of creating and delivering multicomponent interventions for high-risk children and their families. Researchers had experience with Fast Track,16 the largest multisite violence prevention randomized trial ever supported by the National Institute for Mental Health, the first peer-pair coaching program for unpopular children,17 extensions of these university-based programs to community ownership through the dissemination of Fast Track, and research on peer-based interventions to reduce adolescent aggression.18 In addition to this experience in applied intervention research, Duke investigators had conducted extensive basic research on the relationship between social information processing and social adjustment/aggressive behavior19–21 and on the effect of peer rejection on subsequent adjustment.22

Investigators at Duke University began the current project with an extensive history of collaborating with the Durham public schools on violence prevention projects. As one of the sites for the Fast Track project,16,23 a multisite prevention trial to prevent the development of serious conduct problems among at-risk youth, Duke has fostered a 10-year relationship with the Durham public schools. The research group has also collaborated extensively on developing and implementing Durham's Safe Schools/Healthy Students program, a federally funded program to reduce school violence across all grade levels.

The eight Durham middle schools participating in the current project serve approximately 6500 students across grades 6, 7, and 8, and they range in size from just less than 500 students to nearly 1300 students (Table 1). More than 60% of enrolled students are African American (range, 48%–77%), nearly 30% are Caucasian (range, 17%–44%), and fewer are Hispanic (range, 1%–11%), although the number of Hispanic students is increasing rapidly. Nearly 42% are eligible for the federal free and reduced-price lunch program (range, 27%–51%). The most recent end-of-grade test results indicate that approximately 40% of sixth graders at these schools scored below grade level in reading (range, 27%–50%).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of selected schools by site

| site | Schools selected n | Average no. 6th graders n | Racial/ethnic distribution | Eligible free/reduced price lunch % | High school dropout rate % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African American % | Hispanic % | Caucasian % | |||||

| North Carolina (Duke University)a | 8 | 241 | 66 | 5 | 26 | 42 | 2 |

| Georgia (University of Georgia) | 9 | 239 | 34 | 12 | 55 | 47 | 9 |

| Illinois (University of Illinois at Chicago) | 12 | 70 | 46 | 48 | 16 | 96 | 17 |

| Virginia (VA Commonwealth University) | 8 | 236 | 84 | 6 | 9 | 75 | 3 |

Source of racial/ethnic distribution: GREAT pre-test data (percentages in some add to more than 100 because multiple responses were allowed or because of rounding); source of eligibility of free/reduced price lunch and dropout rate: schools of each site.

Youth violence is considered a significant problem in Durham. For the past several years, rates of violence in the Durham schools have been among the highest in the state, according to data compiled by the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction. The rates of suspensions, especially among African-American students, have been alarmingly high, averaging as many as one suspension per student per year at several schools. The dropout rate among students—especially African-American males—has also been consistently above the state average but showed evidence of declining in the most recent year.

The University of Georgia

Investigators at The University of Georgia have been engaged in a number of programs to examine violence reduction in schools. Family and school interventions to reduce aggression in schools and families had been conducted with the Family Therapy Research Program24,25 and with the ACT Early Program (http://www.coe.uga.edu/dev/echd/ACTII.htm), developed to identify and address emotional, behavioral, and academic risk among elementary school children. The University of Georgia researchers also developed the Bully Busters Program to prevent and reduce bullying and victimization in middle schools26,12 and the Family Solutions Program, a multiple-family group intervention program for at-risk youth.27–29 Other research projects related to the assessment and reduction of violence in schools and in the community are the Students for Peace project30,31 and the ACTIVA project (ACTIVA Project [Multicenter Study: Cultural Norms and Attitudes Toward Violence in Selected Cities of Latin America and Spain]).32

Participating schools are urban (n=3) and rural (n=6). Urban schools, located within the immediate vicinity of the university, have a high ratio of low-income students, as evidenced by more than half of the students' receiving free or reduced-price lunches (average, 57%; range, 47%–73%). A high proportion of students belong to racial or ethnic minorities. Of the participating urban schools, 54% of the students are African American (range, 50%–58%), 11% are Hispanic (range, 6%–20%), and 30% are Caucasian (range, 19%–38%). The average high school dropout rate is 12%.

The schools in the rural, outlying area have a heterogeneous economic composition of students. The percentage of students who qualify for free or reduced-price lunches ranges from 19% to 60%, with an average of 41% among schools. The racial and ethnic distribution of students in the rural schools also varies widely by school: African-American students range from 1% to 53% (average, 21%), Hispanic students range from 0% to 15% (average, 4%), and Caucasian students range from 46% to 95% (average, 74%). These rural communities have a lower high school dropout rate (7%) than the urban schools.

Both urban and rural schools are large schools with an average of 215 (range, 136-399) students per grade level (Table 1). Violence and aggression are major problems in both the urban and rural schools. The county where urban schools are located has teen suicide and homicide rates significantly higher than state average, and the high school dropout rate doubles the state rate.33

University of Illinois at Chicago

Investigators at the University of Illinois at Chicago have worked in prevention and risk development research at the Institute of Juvenile Research since 1990. Researchers have focused on a developmental ecologic perspective on family functioning, child psychopathology, and prevention design.34 Their work has been conducted through a long-standing collaboration with the Chicago public schools and the neighborhoods they serve. The primary work has centered on a 10-year longitudinal study of development among inner-city males and their families and female intimate partners through the Chicago Youth Development Study,35 a large multimodal prevention study,36 and the SAFE Children prevention trial.10 These random-assignment trials and multivariate, multilevel risk studies have produced several findings that attest to the validity of the developmental ecologic perspective that is integral to the current project.

The University of Illinois at Chicago serves schools recruited from the Chicago public schools, a large metropolitan school district with more than 500 grade schools and 200 high schools in diverse urban neighborhoods. Unlike the other three sites in the project, middle schools are uncommon in Chicago, where most elementary schools include kindergarten through eighth grade. Neighborhood schools were recruited for the project, as opposed to magnet schools, alternative schools, or specialized academies. Most students in these schools (96%) come from low-income families, as determined by eligibility for federal lunch assistance. The schools for the present project were selected from neighborhoods with rates of poverty and crime higher than average for the city or for the nation as a whole. The ethnic composition of the student population is predominantly African American (46%) and Hispanic (48%), with 16% reporting to be Caucasians (percentages add to more than 100 because students could select multiple responses) (Table 1). In 2000 in Chicago, 57% of sixth graders scored below the national median on the Iowa Test of Basic Skills test of reading comprehension, and only 13% scored in the upper quartile.37

Chicago has high rates of violence in school, and a significant proportion of such violent incidents are gang related.38,39 The scope and seriousness of the problem can be seen in the study by Minden et al.,39 which found that 11% of a sample of 285 male adolescents participating in the Chicago Youth Development Study had used a weapon in school at least once as adolescents, and 8% had used a weapon in school more than once. An additional 36% had participated in violent incidents outside of school. Accordingly, the Chicago Public School district has adopted numerous measures to reduce the occurrence of violence in school and to curtail violence against children on the way to and from school.40

Virginia Commonwealth University

Investigators at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond have a long history of collaboration with the local schools and community. In 1991, researchers began working with the Richmond public schools and several other community organizations to develop effective violence prevention programs for middle school students. Application of an action-research strategy led to a series of studies in which various prevention programs were developed, implemented, evaluated, and revised.41–43 The end product was the Responding In Peaceful and Positive Ways (RIPP) middle school violence program taught by prevention specialists.45 Virginia Commonwealth University researchers gained considerable experience by evaluating this program in Richmond11 and rural Florida.45,46 In addition, they have conducted studies on risk and protective factors in adolescence47 and on the role of cultural and contextual issues in adolescence.48

Middle schools participating in the current project are all within the Richmond public school system. They are all fairly large schools with an average of 180 students per grade level (range, 125–280). The vast majority of students (84%) are African American; 75% are eligible for the federal free or reduced-price lunch program. The school dropout rate is 3% (Table 1). Violence represents a particularly serious problem for these students. On the basis of 1998 statistics, the percentage of students receiving one or more suspensions for violent offenses (i.e., weapons, fighting, assault) during the school year ranged from 13% to 15% across schools for sixth graders and from 15% to 21% for seventh graders.

Overview of the Project

Investigators from NCIPC and the selected universities established working groups and met regularly during a planning year (1999–2000) to establish a collaborative model for working across universities, to develop research questions and an appropriate research design, to determine an overall study timeline, and to develop the interventions to be implemented. Several themes emerged during these discussions and guided the development of the research questions, including achieving agreement about the overall theoretical perspectives to guide the work and the development of the interventions that built on promising strategies, the decision to evaluate the relative effect of universal and targeted approaches and the research questions associated with each, the decision to intervene at the school level, the nature of the interventions being evaluated, the research design, and the measurement strategies.

Theoretical Perspectives and Development of Interventions

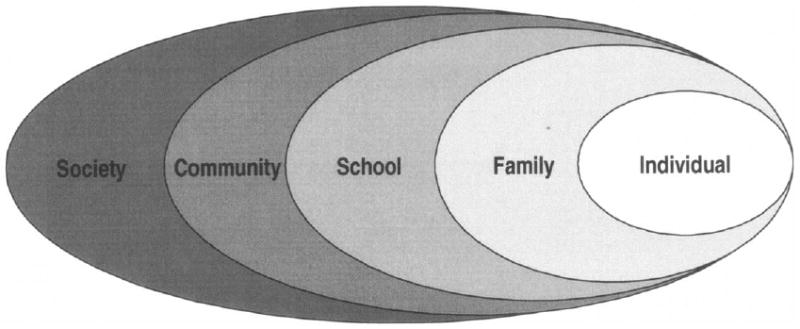

The overarching model was the ecologic model, which helps to understand the multiple factors that interact to increase the levels of risk or protection for violence, as well as the varying types of interventions needed to address violence. The model can be visualized as concentric ellipses in which the student is at the center, surrounded by the family, then the school, the community, and finally society at large (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The ecologic model showing multiple factors that interact.

The child characteristics include individual attributes, such as intellectual functioning, temperament, social and interpersonal skills, and emotional balance. Family characteristics include race and ethnicity, family structure and composition, household membership, family rules and decision-making procedures, financial condition, and interpersonal problem-solving abilities. School characteristics include size, location, climate, and experience of the staff. Community factors include socioeconomic support, emotional support, safety and security within the community, and public support of community standards. Society, a component of influence not addressed in the current study, includes popular entertainment, such as music, films, and television; and social influences that are operating at the national level. The specific theoretical background is described in detail in the papers that describe each of the interventions.2,5,6 The interventions are summarized in the sections that follow. It should be noted that this study was limited to examining violence and aggression against others, not directed toward self, as in suicide.

Universal Versus Targeted Approaches and Research Questions

The importance of reducing aggression among students is clear, but the manner and process for successful achievement are less obvious. Two approaches to reducing violence in schools are universal and targeted (or selected) interventions. A universal intervention is applied in such a manner that all students in the condition receive the intervention. A schoolwide program for teaching anger management would be an example. A targeted intervention is one in which a specific group identified as having a particular problem is selected or targeted to receive an intervention specific to the problem. Involving students with anger control problems in a program on anger management would be an example of a targeted program.

As educators struggle with scarce resources, the question of whether to spend time and money changing the school environment through universal interventions that involve training all teachers and students or to focus on selective interventions that target a small group of high-risk students becomes critical. Some schools have developed in-service training for teachers and schoolwide programs designed specifically to help students learn better emotional and behavioral control skills, with the goal of changing the school climate or culture regarding aggression. Other schools have instituted interventions for those students who cause the most problems and conflict within a school, using a targeted approach of counseling, therapy, in-school suspension, and other problem-focused approaches. There are no clear findings in the research literature that indicate whether a universal or targeted approach is more effective in bringing about school change.

The Multisite Violence Prevention Project, therefore, was designed to answer the following question: Are greater reductions in school aggression found when (1) a violence prevention program is offered to all students and teachers in a particular grade level (universal intervention: student and teacher programs), (2) a program is offered to youths who are at greatest risk for involvement in violence (targeted intervention: family program), or (3) both types of programs are offered (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Number of schools by intervention condition

| Targeted family intervention | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Universal Intervention | Yes | Duke - 2 | Duke - 2 |

| UGA - 2 | UGA - 2 | ||

| VCU - 2 | VCU - 2 | ||

| UIC - 3 | UIC - 3 | ||

| No | Duke - 2 | Duke - 2 | |

| UGA - 3 | UGA - 2 | ||

| VCU - 2 | VCU - 2 | ||

| UIC - 3 | UIC - 3 | ||

Note: Total number of schools is 37.

UGA, The University of Georgia; VCU, Virginia Commonwealth University; UIC, University of Illinois at Chicago.

School Level of Impact

One of the key decisions for this project was to focus on producing and evaluating change at the school level rather than the individual level by implementing universal/school-level and targeted/individual-level interventions that were developed for this project, based on current effective models. The decision to address both the universal and individual level with specific interventions developed for this project was based on theories about mechanisms of change and research design. Because schools are a primary context for social development, they provide a natural opportunity for strategies that focus on promoting nonviolent conflict resolution. Schools also represent a particular social environment in which conflicts can often occur.49 Students spend considerable time at school in close proximity to classmates who may have very different backgrounds and values. The school environment may contain informal social norms for violence in which aggression is used to gain social status and to correct perceived injustices.50 This situation may apply especially to schools in economically stressed communities where prosocial means of achieving status (e.g., school success, employment) are reduced because of limited opportunities or negative attitudes toward such goals.50 Schools may also contribute to the development of aggressive behavior because students interact with deviant peers.51

The types of programs used for violence prevention likely have a limited effect if they are directed at only a portion of the students in a given school. For example, programs designed to change norms will not likely have this ecologic effect unless almost all children are included. Interventions may be able to successfully teach students nonviolent methods of addressing conflicts, but students are not likely to use those skills if they run counter to peer norms or are not otherwise supported within the school environment. Implementing programs on a schoolwide basis also makes it possible to involve teachers and other people in the school in reinforcing program goals and modeling the use of appropriate skills. However, for those children with established and chronic behavior problems, individual and family interventions that provide a more concentrated engagement and increased focus on skill-development and behavioral change specific to the targeted child may be more effective. Thus, the current study examines a universal intervention in comparison to a targeted approach to determine which, if either, results in the greatest reduction of aggression and violence within the school.

Implementing and evaluating programs at the school level may be necessary for methodologic reasons. The nature of the interventions makes it difficult to implement them with only a portion of the students at each school because of the strong possibility of diffusion of treatment effects. Assessing program effects may also be difficult because of the interpersonal nature of aggression. Any reduction in fighting among students in the intervention group may reduce rates of victimization among all students within the school, not just those who participated in the intervention. Similarly, any change in attitudes among students in the intervention group may result in changes in their peers as well. Finally, if interventions effectively reduce school aggression, the interventions are most likely to be implemented schoolwide rather than piecemeal.

The Multisite Violence Prevention Project focused on sixth grade, the level of entry for middle schools. It was decided that the sixth-grade intervention would have the greatest potential effect over several years because the intervention, although not as ideal as a schoolwide implementation, would be provided to those entering the school and remaining for 3 years, thus, having greater potential for influencing the school climate and culture given the financial constraints that limited conducting interventions at all grade levels.

Interventions

The overall program used for the Multisite Violence Prevention Project was the GREAT Schools and Families Program, which built upon previous research in the area.53,54 GREAT is an acronym for Guiding Responsibility and Expectations for Adolescents for Today and Tomorrow. The universal intervention has two components: the GREAT Student Program2 and the GREAT Teacher Program.5 The targeted intervention has one component: the GREAT Families Program.6

The GREAT Student Program is designed to help all sixth-grade students develop social, emotional, and cognitive skills to handle conflict and to enact prosocial norms and behaviors. The program builds on the content of the sixth-grade Responding In Peaceful and Positive Ways (RIPP-6) social–cognitive violence prevention program44; however, it focuses more on changing school norms and explicitly incorporates cultural and contextual goals. The program consists of twenty 45-minute lessons that are taught by trained facilitators once per week.

The GREAT Teacher Program is designed to empower all sixth-grade teachers to prevent aggression and to take a solution-focused approach to problem behavior. In the systemic-ecologic model, teachers are seen as having a powerful influence over the classroom and school. They can increase prosocial behaviors and reduce aggressive behaviors through classroom management practices that emphasize a culture of respect and dignity and through reinforcing and modeling problem-solving skills. The program includes a 12-hour workshop that discusses the extent of the problem of aggression and victimization, prevention and intervention strategies, assistance for students who are the targets of aggression, and teacher coping skills. The workshop is followed by ten support group sessions to discuss concerns about implementing the skills discussed in the workshop, to provide support to teachers, and to solve grade-level and schoolwide problems.

The GREAT Families Program is offered to a subset of sixth-grade students and their families. Participating students have been identified by their teachers as having behavior problems and being influential with other students. The goal of CDC's original request for proposals was to determine the effectiveness of a middle school–based, social–cognitive intervention to reduce violence and to examine the effect of including a community-based intervention that complements the school-based activities. The Multisite Violence Prevention Project determined that the community-based intervention would be a multifamily intervention, as the family has a major effect in the life of the child and yet is independent of the school.52 Rather than focusing on the individual child in isolation, the family program is ecologic in that it includes the child and his or her family in the intervention. The goal of the GREAT Families Program is to enhance parenting skills, family problem solving, communication skills, family awareness of and support during developmental and educational challenges, and family–school linkages. The program consists of 15 lessons taught by a trained facilitator once a week to a group of five to six families.

At each school, the principal was informed of the opportunity to participate in the program; then the faculty and others received a presentation of the project, with an invitation to join the study. Each school was informed of the design and knew that assignment to condition of intervention, including assessment only, would be by random selection. Early on some schools elected not to participate without knowing exactly which condition they would have, and they were excluded from the study. At each school, the principal took an active role in the process of informing teachers, gaining participation of the school staff, and engaging students and families in the consenting process.

Research Design

This project uses a 2 (universal intervention versus no universal intervention) × 2 (targeted intervention versus no targeted intervention) cluster randomized, true experimental design. Within this design, 8 to 12 schools from each site were randomly assigned to one of the four conditions, resulting in a total of 9 schools in each condition. All interventions were implemented in two successive cohorts of students in each intervention school. The assignment of entire schools to conditions complicates the design because students, teachers, and families are nested within conditions and sites. It also requires that the project be conducted on a large scale, involving a large number of schools to ensure that adequate statistical power is achieved. After reviewing a number of alternative designs, investigators determined that this design was best suited to address the research questions of this project.1

Project Period

The project period was from 1999 to 2004. The first year, 1999–2000, was used for planning. During the second year, researchers conducted a pilot evaluation of the intervention and measures. Implementation of the interventions with a first cohort of sixth graders began in the third year, 2001–2002. In the fourth year, the interventions were implemented with a second cohort of sixth graders and a follow-up of the first cohort into seventh grade was conducted. The final year (2003–2004) involves a follow-up of the first cohort into eighth grade and a follow-up of the second cohort into seventh grade.

Measurement

Data collected from multiple sources (teacher, student, family, and archival) and at multiple time points (pretest, posttest, and follow-up) will be used to examine the effect of the interventions on each cohort of students. Because it was not feasible to assess all students in the grade level and because a random selection of students can represent the total population, a random sample of sixth graders was selected to evaluate the grade-level effect of the interventions. This random sample of students and all the targeted students completed a computerized survey. Teachers completed a standardized behavioral survey on all selected students in the universal and targeted cohorts. In addition, all sixth-grade teachers who teach core academic subjects such as language arts or mathematics were asked to complete a survey about their violence prevention skills, their training and experience backgrounds, their efficacy in working with aggressive children, and the school climate regarding decision making and management of student aggression. Parents of the high-risk students also completed a close-ended interview. The outcome measures, as well as impact and moderator measures, are described in the measurement article in this supplement.3

A large number of process measures were developed. The measures covered three components: (1) program integrity, including completeness and fidelity of program implementation; (2) coverage and dosage; and (3) group processes, including a number of factors that may influence the acceptance of the program, such as satisfaction with the facilitator, satisfaction with the program, participation in the program, and external factors (e.g., noise, temperature). These measures will describe the levels and quality of program implementation, to assure and monitor quality of implementation throughout the project period and to explain possible variations in outcomes.

Summary

The Multisite Violence Prevention Project will evaluate the individual and combined effects of two interventions to reduce aggression in middle schools. Study findings will provide important and much-needed knowledge about what works to prevent youth violence.

This paper provides an overview of the history and main components of the project. The remaining papers in this supplement provide greater detail about the two components of the universal intervention, the GREAT Teacher Program5 and the GREAT Student Program,2 and about the targeted intervention, the GREAT Families Program.6 They will also discuss the design of the project1; the challenges faced and lessons learned4; and the measurement instruments, sample, and procedures.3

References

- 1.Henry DB, Farrell AD, Multisite Violence Prevention Project The study designed by a committee: design of the Multisite Violence Prevention Project. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26(suppl):12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyer AL, Allison KW, Reese LE, Gay FN, Multisite Violence Prevention Project Choosing to be violence free in middle school: the student component of the GREAT Schools and Families universal program. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26(suppl):20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller-Johnson S, Sullivan TN, Simon TR, Multisite Violence Prevention Project Evaluating the impact of interventions in the Multisite Violence Prevention study: samples, procedures, and measures. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26(suppl):48–61. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Multisite Violence Prevention Project. Lessons learned in the Multisite Violence Prevention Project collaboration: big questions require large efforts. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26(suppl):62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orpinas P, Horne AM, Multisite Violence Prevention Project A teacher-focused approach to prevent and reduce students' aggressive behavior: the GREAT Teacher Program. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26(suppl):29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith EP, Gorman-Smith D, Quinn WH, Rabiner DL, Tolan PH, Winn DM, Multisite Violence Prevention Project Community-based multiple family groups to prevent and reduce violent and aggressive behavior: the GREAT Families Program. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26(suppl):39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Youth violence: a report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services; and National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crockett LJ, Petersen AC. Adolescent development: health risks and opportunities for health promotion. In: Millstein S, Petersen AC, Nightingale E, editors. Promoting the health of adolescents. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993. pp. 13–37. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orpinas P, Horne AM. Bullies and victims: a challenge for schools. In: Lutzker J, editor. Violence prevention. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; In press. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Henry DB, Quintana E, Lutovsky K. SAFE Children: a preventive intervention for urban families. In: Tolan P, Szapocznik J, Sombrano S, editors. Developmental approaches to prevention of substance abuse and related problems. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; In press. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farrell AD, Meyer AL, White KS. Evaluation of Responding in Peaceful and Positive Ways (RIPP): a school-based prevention program for reducing violence among urban adolescents. J Clin Child Psychol. 2001;30:451–63. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3004_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newman DA, Horne AM, Bartolomucci CL. Bully Busters: a teacher's manual for helping bullies, victims, and bystanders. Champaign IL: Research Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quinn WH, Bell K, Ward J. Early intervention with juvenile offenders: the Family Solutions Program. Prev Res. 1997;4:10–2. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Loeber R, Henry DB. Relation of family problems to patterns of delinquent involvement among urban youth. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1998;26:319–33. doi: 10.1023/a:1021995621302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sayger TV, Horne AM, Glaser BA. Marital satisfaction and social-learning family-therapy for child conduct problems—generalization of treatment effects. J Marital Fam Ther. 1993;19:393–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.1993.tb01001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. A developmental and clinical model for the prevention of conduct disorders: the Fast Track Program. Dev Psychopathol. 1992:509–27. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oden S, Asher SR. Coaching children in social skills for friendship making. Child Dev. 1977;48:495–506. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller-Johnson S, Costanzo P. If you can't beat ‘em…induce them to join you: peer-based interventions during adolescence. In: Kupersmidt JB, Dodge KA, editors. Children's peer relations: from development to intervention to policy. A festschrift in honor of John D Coie. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; In press. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dodge KA, Crick NR. Social information-processing bases of aggressive-behavior in children. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1990;16:8–22. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Renshaw PD, Asher SR. Children's goals and strategies for social interaction. Merrill-Palmer Q. 1983;29:353–74. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rabiner DL, Keane SP, MacKinnon-Lewis C. Children's beliefs about familiar and unfamiliar peers in relation to their sociometric status. Dev Psychol. 1993;29:236–43. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller-Johnson S, Coie JD, Maumary-Gremaud A, Bierman K. Peer rejection and aggression and early starter models of conduct disorder. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2002;30:217–30. doi: 10.1023/a:1015198612049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Initial impact of the Fast Track prevention trial for conduct problems: I. The high-risk sample. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:631–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horne A, Sayger T. Treatment of conduct disordered and oppositional defiant disorders of children. New York: Pergamon Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sayger TV, Horne AM, Walker JM, Passmore JL. Social learning family therapy with aggressive children: treatment outcome and maintenance. J Fam Psych. 1988;1:261–85. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newman D, Horne AM. The effectiveness of a psychoeducational intervention for classroom teachers aimed at reducing bullying behavior in middle school students. J Counseling Dev. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quinn WH. A collaboration of the Family Solutions Program and the Athens/Clarke County Juvenile Court. In: Chibucos T, Lerner R, editors. Success stories: serving children and families through community-university partnerships. Boston: Kluwer; 1999. pp. 89–100. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quinn WH, VanDyke DJ. At-risk youth in the United States: current status, family influence and the Family Solutions Program. In: Pervova I, editor. People, time, society. St. Petersburg, Russia: St. Petersburg University Press; 2001. pp. 66–85. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quinn WH, VanDyke DJ, Kurth ST. A brief multiple family group model for juvenile first offenders. In: Figley C, editor. Brief treatments for the traumatized. Westport CT: Greenwood; 2002. pp. 226–51. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelder SH, Orpinas P, McAlister A, Frankowski R, Parcel GS, Friday J. The Students for Peace Project: a comprehensive violence-prevention program for middle school students. Am J Prev Med. 1996;12:22–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orpinas P, Kelder S, Frankowski R, Murray N, Zhang Q, McAlister A. Outcome evaluation of a multi-component violence-prevention program for middle schools: the Students for Peace project. Health Educ Res. 2000;15:45–58. doi: 10.1093/her/15.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orpinas P. Who is violent? factors associated with aggressive behaviors in Latin America and Spain. Panam J Public Health. 1999;5:232–44. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49891999000400007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boatright SR, Bachtel DC. The Georgia County guide 2002. Athens, GA: Center for Agribusiness and Economic Development at The University of Georgia; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tolan PH, Guerra NG, Kendall PC. A developmental-ecological perspective on antisocial-behavior in children and adolescents—toward a unified risk and intervention framework. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:579–84. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.4.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D, Henry DB. Developmental ecology of urban males' youth violence. Dev Psychol. 2003;39:274–91. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Metropolitan Area Child Study Research Group. A cognitive-ecological approach to preventing aggression in urban settings: initial outcomes for high-risk children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:179–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chicago Public Schools Office of Research and Accountability. Iowa Tests of Basic Skills citywide results over time—1997 to 2003 (Reading) [July 21, 2003]; http://research.cps.k12.il.us/resweb/SiteServlet?page=citywide.

- 38.Gonzalez M. Gang violence in Chicago public schools. Chicago: Urban Youth Journalism Program; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Minden J, Henry DB, Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D. Urban boys' social networks and school violence. Professional Sch Counselor. 2000;4:95–104. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chicago Public Schools, Office of School and Community Relations. Additional Programs and Services. [July 21, 2003]; http://www.cps.k12.il.us/AboutCPS/Departments/OSCR/Programs/programs.html.

- 41.Farrell AD, Meyer AL, Kung EM, Sullivan TN. Development and evaluation of school-based violence prevention programs. J Clin Child Psychol. 2001;30:207–20. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3002_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meyer AL, Farrell AD. Social skills training to promote resilience and reduce violence in African American middle school students. Educ Treatment Child. 1998;21:461–88. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Farrell AD, Meyer AL. The effectiveness of a school-based curriculum for reducing violence among urban sixth-grade students. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:979–84. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.6.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meyer AL, Farrell AD, Northup W, Kung EM, Plybon L. Promoting non-violence in early adolescence: responding in Peaceful and Positive Ways. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Farrell AD, Valois RF, Meyer AL, Tidwell RP. Impact of the RIPP Violence Prevention Program on rural middle school students. J Primary Prev. 2002;33:167–72. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Farrell AD, Valois RF, Meyer AL. Evaluation of the RIPP-6 violence prevention program at a rural middle school. Am J Health Educ. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sullivan TN, Farrell AD. Identification and impact of risk and protective factors for drug use among urban African American adolescents. J Clin Child Psychol. 1999;28:122–36. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2802_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Allison KW, Burton L, Marshall S, et al. Life experiences among urban adolescents: examining the role of context. Child Dev. 1999;70:1017–29. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carlo G, Fabes RA, Laible D, Kupanoff K. Early adolescence and prosocial moral behavior II: the role of social and contextual influences. J Early Adol. 1999;19:133–47. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fagan J, Wilkinson DL. Social contexts and functions of adolescent violence. In: Elliott DS, Hamburg BA, Williams KR, editors. Violence in American schools: a new perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1998. pp. 55–93. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dishion TJ, Patterson GR, Griesler PC. Peer adaptations in the development of antisocial behavior: a confluence model. In: Huesmann LR, editor. Aggressive behavior: current perspectives. New York: Plenum Press; 1994. pp. 61–95. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Orpinas P, Murray N, Kelder S. Parental influences on students' aggressive behaviors and weapon carrying. Health Educ Behav. 1999;26:774–87. doi: 10.1177/109019819902600603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Greenberg MT, Kusche CA, Cook ET, Quamma JP. Promoting emotional competence in school-aged children—the effects of the Paths Curriculum. Dev Psychopathol. 1995;7:117–36. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reid JB, Eddy JM, Fetrow RA, Stoolmiller M. Description and immediate impacts of a preventive intervention for conduct problems. Am J Community Psychol. 1999;27:483–517. doi: 10.1023/A:1022181111368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]