Summary

In Drosophila embryos, boundaries of lineage restriction separate groups of cells, or compartments. engrailed is essential for specification of the posterior compartment of each segment, and its expression is thought to mark this compartment. Using a new photoactivatable lineage tracer, we followed the progeny of single embryonic cells marked at the blastoderm stage. No clones straddled the anterior edges of engrailed stripes (the parasegment border). However, posterior cells of each stripe lose engrailed expression, producing mixed clones. We suggest that stable expression of engrailed by cells at the anterior edge of the stripe reflects, not cell-intrinsic mechanisms, but proximity to cells that produce Wingless, an extracellular signal needed for maintenance of engrailed expression. If control of posterior cell fate parallels control of engrailed expression, cell fate is initially responsive to cell environment and cell fate determination is a later event.

Introduction

One of the outstanding mysteries in developmental biology concerns the mechanism of cell fate determination. Classical genetic experiments suggested a view of Drosophila embryos as a mosaic of patches of determined cells, each contributing to distinct territories in the adult body. In these experiments, single embryonic cells were marked genetically by induced mitotic recombination, and the territory of marked cells in the adult was examined. The clones of marked daughter cells formed contiguous patches of the adult cuticle. The distribution and shapes of these clones appeared haphazard, except for one strikingly nonrandom feature: there were specific boundaries that clones did not straddle. For example, two clonal boundaries–the antero-posterior compartment border (Garcia-Bellido et al., 1973,1976) and the prospective segment border (Wieschaus and Gehring, 1976; Szabad et al., 1979)–enclose the posterior and anterior compartments in each segment primordium. These experiments demonstrate a heritable distinction between cells destined to form anterior and posterior compartments.

The engrailed gene is required only in cells of the posterior compartment. In its absence, these cells adopt other fates, and do not respect the compartment border (Garcia-Bellido and Santamaria, 1972; Morata and Lawrence, 1975; Lawrence and Morata, 1976a; Kornberg, 1981; Brower, 1984). The selector gene hypothesis proposed that engrailed is not only necessary for posterior fate, but actually specifies (or selects) this fate (Garcia-Bellido, 1975). This hypothesis predicted that engrailed expression, and thus function, would be limited to posterior cells. If it is to mark a stable lineage compartment, whatever limits engrailed function to posterior cells must be heritably transmitted.

The cloning of engrailed and analysis of its expression appeared to support this model. In the early embryo, engrailed is expressed in a series of stripes that align with the primordium of the posterior of each segment (Kornberg et al., 1985; DiNardo et al., 1985; Fjose et al., 1985). Indeed, the pattern and timing of engrailed expression fit expectations so closely that engrailed expression has often been taken as a marker of the posterior compartment, despite the fact that a precise correspondence between engrailed expression and an embryonic lineage compartment has never been documented.

If engrailed-expressing cells continuously mark a lineage compartment from the earliest time of engrailed expression, the state of engrailed expression (either on or off) must be maintained in all the descendants of blastoderm cells. Here, we test this directly using a new photoactivatable lineage tracer. We define the pattern of engrailed gene expression in relation to the descendants of single marked blastoderm cells. No clones straddled the anterior edge of engrailed stripes, suggesting that a boundary of lineage restriction is established at the anterior edge of the engrailed stripe during cell cycle 14. However, during the developmental period between 3 and 7 hr AED (after egg deposition), engrailed expression is not faithfully maintained in all the daughters of expressing cells. These “unstable” cells lie at the posterior of the engrailed stripe. The changes observed in engrailed expression challenge traditional interpretations suggesting a close relationship between initial engrailed expression and the establishment of a lineage compartment, and support the proposed existence of an early regulative phase of engrailed control (DiNardo and O'Farrell, 1987; DiNardo et al., 1988; for a review, see DiNardo and Heemskerk, 1990).

Results

A Novel Lineage Tracing Method

To a large extent, the precise mapping of fates during embryogenesis has relied on injection of single cells with a visible lineage tracer (Weisblat et al., 1978; Gimlich and Braun, 1985). Recent advances have provided a less invasive and more powerful strategy, namely local photoactivation of fluorescence. Tim Mitchison devised a caged nonfluorescent derivative of fluorescein, aminofluorescein-bis (1-nitro-4-oxyacetyl-benzyl) ester, subsequently called CF in this paper (see Mitchison, 1989; J. Minden, V. Foe, and T. Mitchison, unpublished data). This reagent is made fluorescent by photohydrolytic removal of the two caging adducts by illumination with 350 nm light. Thus, as first shown by J. Minden, an embryo can be loaded with the caged reagent before cellularization and, at the desired stage, individual cells can be marked by illumination with a microbeam of 350 nm light.

To make this reagent suitable for lineage tracing, we linked CF to dextran and to a nuclear localization peptide (see Experimental Procedures). Linkage to dextran prevents movement of the reagent from cell to cell (Gimlich and Braun, 1985). The nuclear localization peptide adds several features desirable for lineage tracing. Firstly, a clone of marked cells appears as a number of easily discernable fluorescent nuclei rather than a blob of fluorescence. Additionally, the accuracy with which a single cell can be targeted by the photoactivating beam is improved, because nuclear localization physically separates the targets of photoactivation. Since the label contains a lysine-bearing peptide, it is fixed by formaldehyde. No degradation of the label is apparent 10 hr after photoactivation (in 13 hr old embryos). The behavior of marked cells can also be traced in the live embryo. This method should be applicable to the study of cell fate and cell migration in many organisms.

The State of engrailed Expression Is Not Clonally Inherited

After 13 syncytial divisions, the Drosophila embryo cellularizes at the blastoderm stage. Stripes of engrailed expression form upon cellularization (2.5–3 hr AED; cell cycle 14). Most cells of the prospective larval ectoderm go through three postblastoderm divisions (mitoses 14, 15, and 16) prior to germband retraction and then exit the cell division cycle permanently (Lehner and O'Farrell, 1990).

We address whether the distinction between engrailed-expressing and non-engrailed-expressing cells is stable during the postblastoderm divisions. If an early distinction were stable, single cells randomly marked at the blastoderm stage should only give rise to two types of clones, engrailed-expressing clones and non-engrailed-expressing clones. In all our experiments, single cells were marked at the cellular blastoderm stage (2.5 hr AED; cell cycle 14). We typically marked 5–6 well-separated cells (Figure 1) in the prospective dorso-lateral trunk region (fate map from Hartenstein et al., 1985). This operation was repeated on several embryos from the same collection. After marking, the embryos were left to develop to allow cell division. Embryos were subsequently fixed, stained with an anti-engrailed antibody, and viewed by two-channel immunofluorescence to detect both the clones and engrailed staining (Figure 2). We report here the results of four separate experiments. In all four experiments, three types of clones were identified (see Table 1). These include the two expected types, engrailed-expressing and non-engrailed-expressing. In addition, we found mixed clones that straddled the boundary between engrailed-expressing and nonexpressing cells.

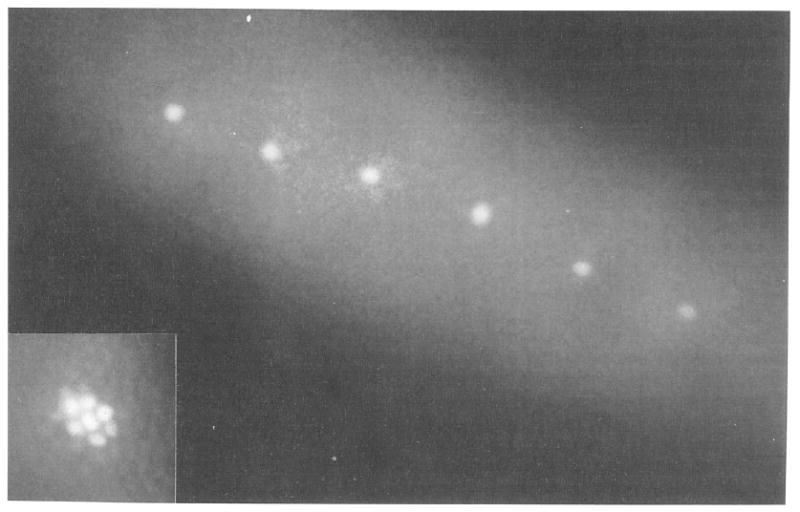

Figure 1.

Single Nuclei Marked by Photoactivation

Live cellular blastoderm viewed in epifluorescence microscopy. The embryo was injected with nonfluorescent Dx-CF-NLS before cellularization. Single nuclei were made fluorescent during cellularization by illumination with a microbeam of 365 nm light. Inset: to show nuclear localization of the activated fluorescence, a group of nuclei in a different embryo were marked with a wider microbeam.

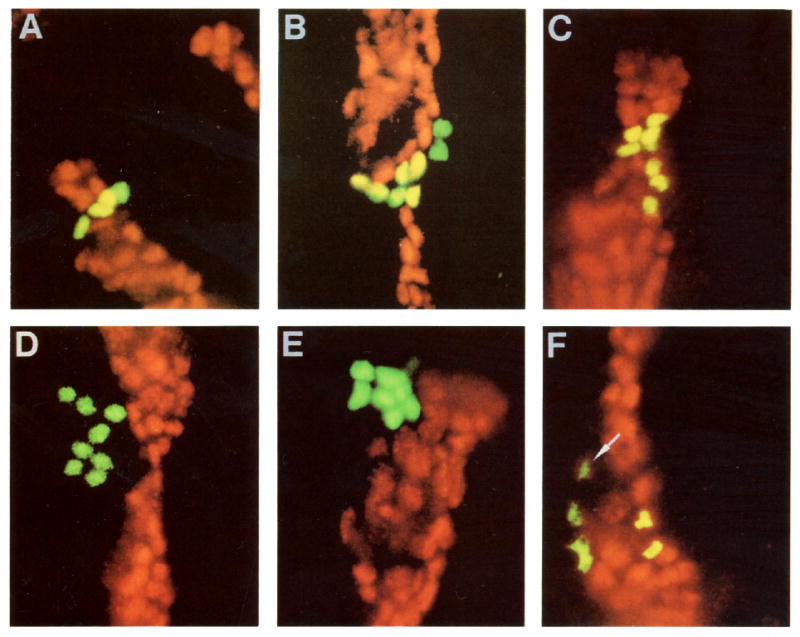

Figure 2.

Mapping Clone Territories with Respect to engrailed Expression

Double exposures showing a marked clone in green and engrailed in red. Coincidence of the two fluorescent signals is seen as yellow. Various types of clones are shown: two “mixed clones” (A and B), two clones of engrailed-expressing cells (C and F), and two nonexpressing clones (D and E). In (A), the embryo was fixed between the second and third postblastoderm divisions (stage 10) and, as expected, the marked clone comprises 4 cells. In (B)–(F), embryos were fixed soon after the third postblastoderm division (stage 11). Notice, in (F), the weaker engrailed-expressing cell at the anterior border of the stripe. The outer edge of the green signal (the clonal marker) was truncated to allow the weak red (engrailed) signal to be seen. Only 6 of the 8 cells of this clone are visible; the remaining two were in a different plane of focus. In this and subsequent figures, posterior is to the right and dorsal is up.

Table 1.

Inventory of Clone Types

| Expt. 1 2 div. |

Expt. 2 3 div. |

Expt. 3 3 div. |

Expt. 4 3 div. |

Total 2 and 3 div. |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| en-expressing clones | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 22 |

| Clones straddling posteriorly | 6 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 15 |

| Clones straddling anteriorly | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Non-en-expressing clones | 21 | – | – | – | – |

The different types of clones obtained in four separate experiments were counted and inventoried. Non-engrailed-expressing clones were not counted in experiments 2, 3 and 4 as indicated by –. Clones straddling anteriorly and posteriorly refer to clones straddling the anterior and the posterior edge of the engrailed stripe, respectively. Notice that no clones straddling the anterior edge were seen.

The time of embryo fixation differed in the various experiments. At the time of embryo fixation in the first experiment (5 hr AED), two postblastoderm divisions had occurred (most marked cells produced 4-cell clones). Of the 31 clones analyzed in this experiment, 4 contained only engrailed-expressing cells, 21 contained only non-engrailed-expressing cells, and 6 contained a mixture of expressing and nonexpressing cells. In the other three experiments, in which the embryos were fixed at a later stage (6–8 hr AED), all three postblastoderm divisions should have been completed. Indeed, in these experiments, almost all clones contained 6–8 cells. When the results of these three experiments are compiled, we find 9 mixed clones and 18 clones whose members were confined to the engrailed expression domain (the number of non-engrailed-expressing clones was not recorded). One example of an early clone (after two divisions), and several examples of late clones (after three divisions) are shown in Figure 2. The mixed clones show that the distinction between engrailed-expressing and nonexpressing cells is not stable at the blastoderm stage.

Half of the mixed clones in embryos fixed after two cell divisions (the first experiment) consisted of 3 engrailed-expressing cells and 1 nonexpressing cell. This is evidence that a stable distinction between engrailed-expressing and nonexpressing cells has not taken place at least until after mitosis 15, more than 2 hr after blastoderm. With the available data, we are not able to tell whether a distinction is established before mitosis 16.

A Lineage Restriction Exists

Two classes of mixed clones are possible: clones that straddle the anterior edge of the engrailed stripe and clones that straddle its posterior edge. As seen in Table 1, only one type is found. No clones that straddle the anterior boundary of the engrailed stripe were found, while 15 clones straddled the posterior boundary. Thus, our results show that the anterior edges of engrailed stripes, when visualized in the germband extended embryo, correspond to boundaries of clonal restriction established at the cellular blastoderm stage.

Mixed Clones Arise by Decay of engrailed Expression

Mixed clones could arise in two ways. Expression of engrailed could cease in some of the descendants of cells that initially expressed engrailed. Alternatively, the descendants of non-engrailed-expressing blastoderm cells could start expression following the first postblastoderm division. To distinguish these possibilities, we analyzed embryos that carry a lac Z reporter inserted at engrailed (β-galactosidase expression is under the control of the engrailed promoter; ryxho25, Hama et al., 1990). We stained these embryos with antibodies against engrailed and against β-galactosidase. Since the engrailed protein is unstable, its level is a close reflection of current gene expression. In contrast, β-galactosidase appears to be more stable, so that its presence provides a record of past engrailed expression. If a cell shuts off engrailed expression, for some time it will contain β-galactosidase and no engrailed product. Thus, we can detect decay of engrailed expression. Conversely, we can also detect de novo engrailed expression. Since β-galactosidase expression in ryxho25 embryos is delayed relative to the expression of the resident engrailed gene (Hama et al., 1990), a cell that switches on engrailed will be recognizable as containing the engrailed product, but not β-galactosidase.

We find cells containing β-galactosidase and not the engrailed product. These cells are always found at the posterior edge of the engrailed stripe (Figure 3), the same boundary that is straddled by mixed clones. Cells near the posterior edge of engrailed stripes that have very low levels of engrailed product were losing engrailed expression when the embryo was fixed, as they contain β-galactosidase (Figure 3, arrow). Thus, selective loss of engrailed expression takes place at the posterior boundary of engrailed stripes during germband extension, and the “on” state of engrailed expression is not stable at this stage.

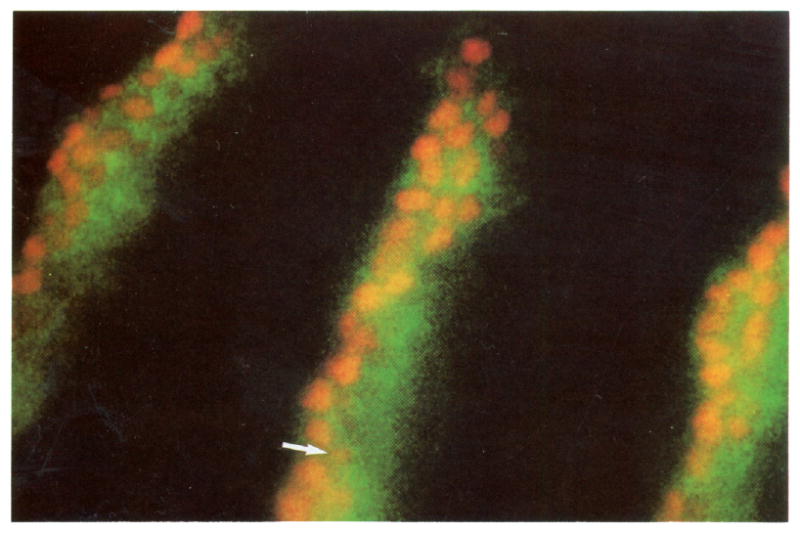

Figure 3.

Perdurance of β-Galactosidase Signal in ryxho25 Cells That Previously Expressed engrailed

Stage 10 embryo stained with anti-engrailed (red) and anti-β-galactosidase (green). In the ryxho25 line, β-galactosidase is expressed from an engrailed promoter and closely follows the engrailed pattern of expression. But because β-galactosidase is a more stable protein, its signal perdures longer than the engrailed signal. Posterior to the engrailed stripes, cells contain β-galactosidase and no detectable engrailed. Notice also cells with a very low level of engrailed signal (arrow). These cells always contain β-galactosidase.

Does de novo engrailed expression also contribute to mixed clones? The clones we have examined were all induced in the trunk region of the dorsal ectoderm (between stripes 4 and 12). We detected no new expression of engrailed in the region of the embryo where we analyzed clones. While de novo engrailed expression does occur in other positions of the embryo (our unpublished data), it does not contribute to the mixed clones described here.

If, as predicted by the above analysis, there is loss of engrailed expression, the number of engrailed-positive cells in a stripe should be affected. Indeed, cell counts show that the number of engrailed-expressing cells does not increase as much as would be expected from the number of mitoses. For example, stripe 4, which starts with an average of 52 cells at the onset of germband extension (before any postblastoderm division), contains only an average of 128 cells at late stage 10 instead of the 208 expected after two postblastoderm divisions. This is consistent with loss of engrailed expression in a substantial number of cells. This is in contrast with findings in grasshopper and crayfish where new engrailed expression is detected (Patel et al., 1989). Intriguingly, however, new expression occurs only at the posterior edge of engrailed stripes, and therefore, in these organisms too, no changes in engrailed expression take place at the anterior edge of engrailed stripes during early stages of development.

As mentioned above, we find cells with low levels of engrailed product toward the posterior edge of the stripe. In contrast to this graded decline in engrailed staining at the posterior side of the stripes seen during germband extension, the anterior edges of engrailed stripes are well defined. At late germband extended stages, shortly before retraction, the polarity of this pattern reverses, with weak engrailed-expressing cells being found at the anterior end of each stripe. We think that these weak expressing cells are clonally related to full-fledged members of the stripe, since we found clones that include both faint and intensely staining cells (see Figure 2F). We are now investigating whether engrailed expression will stably remain weak in these cells or whether it will be extinguished.

Discussion

Drosophila is often said to follow a mosaic pattern of development. In mosaic development, different parts of an embryo follow autonomous developmental programs, each contributing to a different part of the adult body. This perspective has evolved from (although it was not proven by) the classical experiments demonstrating that the early embryo is subdivided into a series of cell populations having distinct lineages. Distinct lineages have been proposed to be established by the stable activation of specific “selector” or “fate-determining” genes (Garcia-Bellido, 1975; Lawrence and Morata, 1976b). Our data suggests another view, at least with respect to the regulation of expression of a putative fate-determining gene, engrailed.

We show that engrailed expression is not heritably transmitted during mitoses 14 and 15. The orderly decay of expression in cells toward the posterior of each stripe argues that maintenance of expression is controlled by processes sensitive to the positions of the cells. Our analyses are consistent with a suggestion that determination of the state of engrailed expression is delayed until after a period of regulative control based on cell communication (DiNardo et al., 1988; Heemskerk et al., 1991; see also below). Owing to the established requirement of engrailed for posterior development, we anticipate that control of posterior cell fate parallels the control of engrailed expression. This suggests that cell fate, like engrailed expression, is controlled by cell interactions during a phase of early development.

Interestingly, we find that the anterior edge of the engrailed stripe corresponds to a boundary of lineage restriction. It is this stable aspect of engrailed expression that allows us to integrate our observations with classical studies showing clonal restriction at the antero-posterior compartment border by mitosis 15 (e.g., Garcia-Bellido et al., 1973).

How Stable Is Clonal Restriction at the Anterior Edges of engrailed Stripes?

We have detected 15 clones that straddle the posterior edge of the engrailed stripe, and none that straddle the anterior. We expect that, in the absence of perturbation, clones will consistently respect the anterior boundary during the three postblastoderm divisions. This supposition is supported by our comparison of patterns of Engrailed protein staining to patterns of accumulated β-galactosidase expressed from the engrailed promoter. Because β-galactosidase is stable and the Engrailed protein is unstable, Engrailed protein levels provide a measure of current levels of expression, while β-galactosidase levels depend more on past and cumulative expression. Consequently, changes in engrailed expression over time are obvious as differential staining. These analyses detect no change in engrailed expression, either turn on or turn off, at the anterior edge of the engrailed stripe.

What about stages beyond those that we have examined here? Does the anterior boundary of engrailed expression remain stable and continue to mark a boundary of clonal restriction? Based on studies of fushi tarazu (ftz) and Ultrabithorax (Ubx) and morphological criteria, Martinez Arias and Lawrence (1985) defined a parasegmental boundary in the embryo. It was presumed that this embryonic border is the equivalent of the boundary of clonal restriction mapped on the adult cuticle (Lawrence, 1988). Our results support this interpretation by showing that the anterior edge of the engrailed stripe, which corresponds to the parasegmental boundary, is a boundary of lineage restriction in the embryo. However, we have no data showing the correspondence of this embryonic border with that of the adult boundary of lineage restriction, and it remains to be shown directly whether or not engrailed continues to mark this boundary stably.

Coordination between Distinct Regulatory Programs Can Produce Stable Patterns

Since initial engrailed expression is controlled by pair-rule gene products, it is the localized activities of these regulators that specify the initial position of the anterior edge of the engrailed stripe (Howard and Ingham, 1986; Harding et al., 1986; DiNardo and O'Farrell, 1987; Lawrence et al., 1987; Carroll et al., 1988; Lawrence and Johnston, 1989). How is this initial boundary of expression maintained when the pair-rule regulators decay? We know that following the decay of the pair-rule regulators, engrailed expression comes under the control of a second tier of regulation, which involves segment polarity genes and cell communication (DiNardo et al., 1988). Since this later tier of regulation is capable of reprogramming engrailed expression, the stable features of the engrailed expression pattern require precise coordination between the early and late programs. This coordination appears to follow from the control of the late regulators by the early regulators. That is, pair-rule genes, such as fushi tarazu and even skipped, direct expression of the late regulators, wingless and engrailed, to cells on opposite sides of the parasegmental border (Lawrence et al., 1987; Baker, 1987; Carroll et al., 1988; Ingham et al., 1988): this same boundary is sustained by cell–cell interactions during the second tier of regulation (see below).

A Regulative Model of engrailed Control

Shortly after blastoderm, engrailed expression comes to rely on a cell signaling molecule, the product of the wingless gene (DiNardo et al., 1988; Martinez Arias et al., 1988). Since, by definition, the determined state is maintained by cell-autonomous mechanisms (Slack, 1983), the state of engrailed expression cannot be determined as long as the wingless product, a cell-extrinsinc regulator, is required. The orderly loss of engrailed expression at the posterior of each stripe, and the dissimilar behavior of the two edges of the engrailed stripe, can be explained by a model based on the wingless product dependency. As a result of pair-rule control, the Wingless protein is initially expressed and secreted by cells that lie immediately anterior to the engrailed-expressing cells (Rijsewijk et al., 1987; Cabrera et al., 1987; Martinez Arias et al., 1988; DiNardo et al., 1988; Van den Heuvel et al., 1989; Gonzalez et al., 1991). The model proposes that cells near the anterior edge of the engrailed stripe would receive a large dose of Wingless signal sufficient to maintain engrailed expression, while, further away, the Wingless signal would be too low to maintain expression. Thus, in the undisturbed embryo, the cell-extrinsic signals that control engrailed expression reinforce and maintain the initial border of engrailed expression established by pair-rule gene control.

The dependency of engrailed on wingless is transient (Bejsovec and Martinez Arias, 1991; Heemskerk et al., 1991), and it has been suggested that loss of dependency (at about 5 hr AED) represents a step in the progression from a regulative control to determination of engrailed expression (Heemskerk et al., 1991). Transition to a determined state of engrailed expression would correspond to the establishment of a true posterior compartment in each segment.

The Segment Border

The lineage relationship of engrailed-expressing cells that we report here applies to the germband extended stage of development. Unless engrailed expressing cells, which change their states of expression between the blastoderm and the extended germband stages, stably maintain the state of engrailed expression thereafter, further change will occur. Whereas one might expect that continued changes in engrailed expression would erode earlier lineage relationships, the opposite is observed. We have preliminary data indicating that cells marked at blastoderm rarely produce clones that straddle the segment border in a germband shortened embryo. Since the segment border at this stage corresponds to the posterior edge of the engrailed stripe (our unpublished data), this result requires that the number of clones straddling the posterior edge of the stripes diminish between the germband extended and germband shortened stages. Although this phenomenon is still under investigation, we offer the following proposal to explain how it might occur.

Blastoderm cells rearrange and condense to form the germband during early germband extension. As a consequence, the single-cell-wide stripe of engrailed-expressing cells becomes two cells wide. At this point, an engrailed stripe can be considered to consist of two kinds of cells, those juxtaposed to wingless-expressing cells and those no longer juxtaposed. Perhaps this distinction biases the future behavior of cells (i.e., those cells closer to the wingless-expressing cell may express engrailed more stably because they are exposed to a higher dose of the Wingless signal). Analysis at the germband extended stage may catch the embryo in the midst of a transition in which the daughters of cells that received a low dose of Wingless are losing expression. If all the daughters of these unstably expressing cells eventually lose engrailed expression, the mixed clones will disappear. However, this loss might not be so thorough. Cell movement may sometimes bring a descendant of a nonjuxtaposed cell back in the vicinity of wingless-expressing cells. This situation would give a “sloppy” clonal restriction.

The model suggested above reconciles our observations with earlier studies suggesting the establishment, at the blastoderm stage, of a boundary of lineage restriction at the segment border (Wieschaus and Gehring, 1976). These earlier experiments are comparable to ours, since in both studies, cells were marked at cycle 14. While the earlier genetic study did not detect any violation of the segment border among the few clones that were analyzed, we did detect occasional clones straddling the segment border. This is most easily explained if the fate of blastoderm cells is biased but not determined.

In summary, we suggest that the interaction between wingless- and engrailed-expressing cells results in a stable clonal boundary where they are apposed at the parasegmental boundary, and a sloppy boundary at the limit of effective action of the Wingless signal. Initial boundary maintenance does not depend on cell-intrinsic maintenance of engrailed expression, but such a mechanism may come into play after mitosis 16 (Heemskerk et al., 1991).

Experimental Procedures

Synthesis of Dx-CF-NLS

The first-generation caged fluorescein (Mitchison, 1989) is not very water soluble. A new, soluble compound, Aminofluorescein-bis (1-nitro-4-oxyacetyl-benzyl) ester, has since been made (T. Mitchison, unpublished data; detailed information can be obtained from Tim Mitchison, UCSF). For short, we call the soluble version CF (caged fluorescein). Amino dextran was sequentially conjugated to CF and a nuclear localization peptide according to the following protocol. Dextran (70 kd, 36 amino groups per mol; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was dissolved in dry dimethylsulfoxide at 50 mg/ml. A small amount of triethylamine was added as a proton acceptor. CF-sulfo-NHS-ester (gift of Tim Mitchison, UCSF) was added from a 100 mM stock in dimethylsulfoxide to give a final concentration of 2 mol per mol dextran. After 30 min reaction, iodoacetic acid–NHS-ester (Sigma) was added from a stock of 50 mg/ml in dimethylsulfoxide to give a final concentration of 50 mol per mol dextran. This linker group adds iodoacetate groups to dextran for subsequent coupling to the cysteine of a nuclear localization peptide. The reaction was allowed to take place for 30 min and was subsequently dialyzed (12 kd cutoff) against 100 mM HEPES (pH 7) (6 hr, 3 changes). Nuclear localization peptide was added from a 10 mg/ml stock in water to a final concentration of 10 peptide mol per mol dextran and allowed to react overnight with labeled dextran. The unreacted iodoacetate groups were reduced with 5% BME for 10 min. This was followed by dialysis against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The peptide used, polyoma large T; 189–196 (Chelsky et al., 1989), was selected because it had been shown to function in Drosophila embryos (M. Paddy and D. Chelsky, personal communication). The reaction was then dialyzed against PBS. The final product is called Dx-CF-NLS and is shown in schematic form in Figure 4.

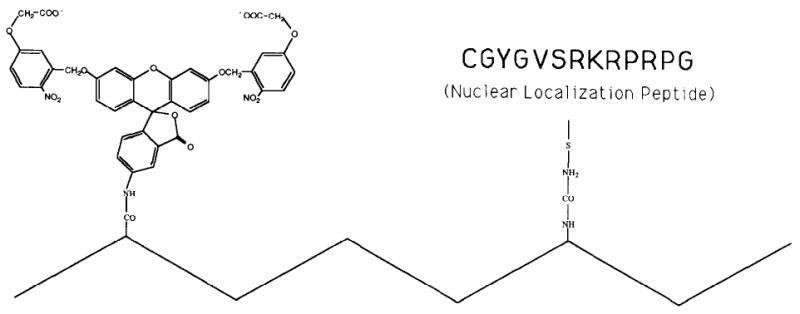

Figure 4.

Schematic Structure of the Lineage Tracer Dx-CF-NLS

The zigzag line represents a chain of 70 kd dextran. From the stoichiometry of the reactions, we estimate that each chain carries, on average, one molecule of CF (structure and reagent provided to us by Tim Mitchison) and ten molecules of nuclear localization peptide (sequence: CGYGVSRKRPRPG-CONH2; gift of Dan Chelsky). Only one copy of the peptide is shown in this diagram.

Photoactivation

In preparation for microinjection, embryos were appropriately oriented on a glue-coated cover slip, desiccated, and covered with halocarbon oil (series 700, Halocarbon Products Corp., Hackensack, NJ). A 1 mg/ml solution of Dx-CF-NLS (concentration estimated from the input of dextran in the initial reaction) was injected into precellular blastoderm embryos. To ensure maximal survival, embryos were cultured at 18°C after injection. Localized photoactivation was done at the cellularization stage with an epifluorescence microscope (Zeiss) modified as follows by Jon Minden (Carnegie Mellon; see also Mitchison, 1989; J. Minden, V. Foe, and T. Mitchison, unpublished data). A 100 μm pinhole was inserted in front of the epifluorescence diaphragm, thus allowing only a small beam from the mercury arc source to enter the epifluorescence tube. A 365 nm barrier filter was used to generate light of the appropriate wavelength for photoactivation. The photoactivating beam was focused on the embryo with a 63 × objective (PlanNeofluar 160/0.12–0.22, Zeiss) immersed directly in the oil covering the embryo. Before the start of an experiment, the beam was imaged with a video camera (5000 series, COHU, mounted on the trinocular head) and its position on the video monitor was recorded with a marker pen. To activate fluorescence in a cell, the embryo, viewed on the video monitor by filtered (red) transillumination, was positioned using the stage control so as to align the chosen cell with the marked position on the video monitor. Photoactivating light, controlled by an electronic shutter (Vincent and Assoc, Rochester, NY), was typically applied for 5–10 s. Several cells (more than 6 cells apart from each other) in a series of embryos were photoactivated in one sitting. The cover slip holding the embryos was then transferred to the imaging microscope (see below) to verify proper photoactivation. Exposure times to record activated fluorescence were less than 0.05 s.

Antibody Staining

The staining of ryxho25 embryos with rabbit anti-β-galactosidase (Cappel, Westchester, PA) and rabbit anti-engrailed (DiNardo et al., 1985) was performed according to standard protocols. Since both antibodies were from rabbit, we directly labeled anti-β-galactosidase with fluorescein n-hydroxysuccinimidylester (fluorescein-SNHS, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) such that a secondary antibody was not needed to see anti-β-galactosidase. The secondary used against rabbit anti-engrailed was Texas red-labeled donkey anti-rabbit (Jackson, PA), diluted 1/300.

Injected embryos (for photoactivation experiments) require special preparation for antibody staining. Since the embryos were loaded with the caged compound, all procedures were done under photographic safe light. At the time of fixation, embryos were washed off the cover slip with a gentle stream of heptane (which dissolves both the glue and the halocarbon oil) and collected in a small plastic dish. The embryos were pipetted (use of plastic tips is essential) along with heptane onto the fix solution (1.5 ml formaldehyde, 37% Sigma, and 3.5 ml PBS) in a 25 ml glass scintillation vial. The vial was gently rocked for 34 min while kept upright to ensure that embryos did not touch the sides of the vial. The embryos were pipetted from the heptane/aqueous interface onto the outer surface of a fine mesh basket stuffed with Kim-wipes. Embryos were blotted once from the inside of the basket and picked from the outside with a strip of double-stick tape. The strip was immediately applied to the bottom of a plastic dish (embryos side up) and submerged under PBS. Embryos were manually devitellinized with the tip of a 21-gauge needle under a dissection microscope with filtered illumination. After manual devitellinization, embryos were ready for standard antibody staining.

Microscopy

Images were recorded with a cooled CCD camera (series 200, Photometrics, Tucson, AZ) equipped with a Kodak chip (KAF1400) and mounted on an epifluorescence microscope (Optiphot, Nikon). Epifluorescence filters were removed from the standard filter cubes and replaced by filters (Omega Optical, Brattleboro, VT) mounted on wheels (Ludl Electronics Products, Hawthorne, NY) positioned at appropriate planes of the microscope. A custom-made dichroic filter (Omega Optical) was mounted on the original cube and used for all filter combinations. Immobility of the dichroic filter ensures a good alignment of pictures taken with different sets of barrier-emission filters. Image processing and much of the control of the microscope hardware (shutters, focusing knob, and the filter wheels) was done with a software package called ISee (Inovision Corp., Durham, NC) running on a Sparc 1 workstation (Sun Microsystems, Sunnyvale, CA). Images were stored digitally and were subsequently manipulated to enhance contrast and/or generate double exposures. False colors in double exposures are chosen arbitrarily; we assigned green to the fluorescein signal and red to the Texas red signal.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tim Mitchison for his generous and abundant advice and for the provision of numerous reagents, especially the newly developed caged fluorescein. Jon Minden devised the photoactivation set up and provided invaluable help with chemistry as well. We thank Dan Chelsky for the gift of large quantities of nuclear localization peptide. Scott Fraser was involved in early attempts to follow the lineage of blastoderm cells with a microinjected lineage tracer. This early work was supported by a grant to Scott Fraser. Thanks to Shelagh Campbell, Charles Girdham, Jim Jaynes, Danesh Moazed, and especially Steve DiNardo, Jill Heemskerk, and Peter Lawrence for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by a NSF grant (P. H. 0.). J.-P. V. was a Damon Runyon–Walter Winchell Fellow (DRG 958) during the early part of this work.

References

- Baker NE. Molecular cloning of sequences from wingless, a segment polarity gene in Drosophila: the spatial distribution of a transcript in embryos. EMBO J. 1987;6:1765–1773. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02429.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejsovec A, Martinez Arias A. Roles of wingless in patterning the larval epidermis of Drosophila. Development. 1991;113:471–485. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.2.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brower D. Posterior-to-anterior transformation in engrailed wing imaginal discs of Drosophila. Nature. 1984;310:496–497. doi: 10.1038/310496a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera C, Alonso MC, Johnston P, Phillips RG, Lawrence PA. Phenocopies induced with antisense RNA identify the wingless gene. Cell. 1987;50:659–663. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll SB, DiNardo S, O'Farrell PH, White RA, Scott MP. Temporal and spatial relationships between segmentation and homeotic gene expression in Drosophila embryos: distributions of the fushi tarazu, engrailed, Sex combs reduced, Antennapedia, and Ultrabithorax proteins. Genes Dev. 1988;2:350–360. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.3.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chelsky D, Ralph R, Jonak G. Sequence requirement for synthetic peptide-mediated translocation to the nucleus. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:2487–2492. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.6.2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNardo S, Heemskerk J. Molecular and cellular interactions responsible for intrasegmental patterning during Drosophila embryogenesis. Sem Cell Biol. 1990;1:173–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNardo S, O'Farrell PH. Establishment and refinement of segmental pattern in the Drosophila embryo: spatial control of engrailed expression by pair-rule genes. Genes Dev. 1987;1:1212–1225. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.10.1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNardo S, Kuner J, Theis J, O'Farrell PH. Development of embryonic pattern in D. melanogaster as revealed by accumulation of the nuclear engrailed protein. Cell. 1985;43:59–69. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNardo S, Sher E, Heemskerk-Jongens J, Kassis J, O'Farrell PH. Two-tiered regulation of spatially patterned engrailed gene expression during Drosophila embryogenesis. Nature. 1988;332:604–609. doi: 10.1038/332604a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fjose A, McGinnis WJ, Gehring WJ. Isolation of a homeo box–containing gene from the engrailed region of Drosophila melanogaster and the spatial distribution of its transcripts. Nature. 1985;313:284–289. doi: 10.1038/313284a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Bellido A. Genetic control of wing disc development in Drosophila. In: Porter R, Elliott K, editors. Cell Patterning (Ciba Foundation Symp. Vol. 29) Amsterdam: Elsevier/North Holland; 1975. pp. 161–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Bellido A, Santamaria P. Developmental analysis of the wing disc in the mutant engrailed of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1972;72:87–104. doi: 10.1093/genetics/72.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Bellido A, Ripoll P, Morata G. Developmental compartmentalization of the wing disc of Drosophila. Nature New Biol. 1973;245:251–253. doi: 10.1038/newbio245251a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Bellido A, Ripoll P, Morata G. Developmental compartmentalization in the dorsal mesothoracic disc of Drosophila. Dev Biol. 1976;48:132–147. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(76)90052-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimlich RL, Braun J. Improved fluorescent compounds for tracing cell lineage. Dev Biol. 1985;109:509–514. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(85)90476-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez F, Swales L, Bejsovec A, Skaer H, Martinez Arias A. Secretion and movement of wingless protein in the epidermis of the Drosophila embryo. Mech Dev. 1991;35:43–54. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(91)90040-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hama C, Ali Z, Kornberg TB. Region-specific recombination and expression are directed by portions of the Drosophila engrailed promoter. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1079–1093. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.7.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding K, Rushlow C, Doyle HJ, Hoey T, Levine M. Cross-regulatory interactions among pair-rule genes in Drosophila. Science. 1986;233:953–959. doi: 10.1126/science.3755551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartenstein V, Technau GM, Campos-Ortega JA. Fate-mapping in wild-type Drosophila melanogaster. III. A fate map of the blastoderm. Roux's Arch Dev Biol. 1985;194:213–216. [Google Scholar]

- Heemskerk J, DiNardo S, Kostriken R, O'Farrell PH. Multiple modes of engrailed regulation in the progression towards cell fate determination. Nature. 1991;352:404–410. doi: 10.1038/352404a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard K, Ingham P. Regulatory interactions between segmentation the genes fushi tarazu, hairy, and engrailed in the Drosophila blastoderm. Cell. 1986;44:949–957. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingham PW, Baker NE, Martinez Arias A. Regulation of segment polarity genes in the Drosophila blastoderm by fushi tarazu and even skipped. Nature. 1988;331:73–75. doi: 10.1038/331073a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornberg T. Compartments in the abdomen of Drosophila and the role of the engrailed locus. Dev Biol. 1981;86:363–372. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(81)90194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornberg T, Siden I, O'Farrell PH, Simon M. The engrailed locus of Drosophila: in situ localization of transcripts reveals compartment-specific expression. Cell. 1985;40:45–53. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90307-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence PA. The present status of the parasegment. Development. 1988;104(suppl):61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence PA, Johnston P. Pattern formation in the Drosophila embryo: allocation of cells to parasegments by even-skipped and fushi tarazu. Development. 1989;105:761–767. doi: 10.1242/dev.105.4.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence PA, Morata G. Compartments in the wing of Drosophila: a study of the engrailed gene. Dev Biol. 1976a;50:321–337. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(76)90155-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence PA, Morata G. The compartment hypothesis. In: Lawrence PA, editor. Insect Development. Oxford, England: Blackwell; 1976b. pp. 132–148. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence PA, Johnston P, Macdonald P, Struhl G. Borders of parasegments in Drosophila embryos are delimited by the fushi tarazu and even-skipped genes. Nature. 1987;328:440–442. doi: 10.1038/328440a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehner C, O'Farrell PH. The role of Drosophila cyclins A and B in mitotic control. Cell. 1990;61:535–547. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90535-m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Arias A, Lawrence PA. Parasegments and compartments in the Drosophila embryo. Nature. 1985;313:639–642. doi: 10.1038/313639a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Arias A, Baker N, Ingham PW. Role of segment polarity genes in the definition and maintenance of cell states in the Drosophila embryo. Development. 1988;103:157–170. doi: 10.1242/dev.103.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchison T. Polewards microtubule flux in the mitotic spindle: evidence from photoactivation of fluorescence. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:637–652. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.2.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morata G, Lawrence PA. Control of compartment development by the engrailed gene in Drosophila. Nature. 1975;255:614–617. doi: 10.1038/255614a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel NH, Kornberg TB, Goodman CS. Expression of engrailed during segmentation in grasshopper and crayfish. Development. 1989;107:201–212. doi: 10.1242/dev.107.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijsewijk F, Schuerman M, Wagenaar E, Parren P, Weigel D, Nusse R. The Drosophila homolog of the mouse mammary oncogene int-1 is identical to the segment polarity gene wingless. Cell. 1987;50:649–657. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack JMW. From Egg to Embryo Determinative Events in Early Development. In: Barlow PW, Green PB, Wylie CC, editors. Developmental and Cell Biology Series. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Szabad J, Schupbach T, Wieschaus E. Cell lineage and development in the larval epidermis of Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol. 1979;73:256–271. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(79)90066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Heuvel M, Nusse R, Johnston P, Lawrence P. Distribution of the wingless product in Drosophila embryos: a protein involved in cell–cell communication. Cell. 1989;59:739–749. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisblat DA, Sawyer RT, Stent GS. Cell lineage analysis by intracellular injection of a tracer enzyme. Science. 1978;202:1295–1298. doi: 10.1126/science.725606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieschaus E, Gehring W. Clonal analysis of primordial disc cells in the early embryo of Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol. 1976;50:249–263. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(76)90150-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]