Abstract

shRNA is a powerful tool for inhibiting gene expression. One limitation has been that this technique has been used primarily to target a single gene. This protocol expands upon previous methods by describing a knockdown vector that facilitates cloning of multiple shRNAs; this allows targeted knockdown of more than one gene or of a single gene that may be otherwise difficult to knockdown using a single shRNA. The targeted gene(s) can be readily re-expressed by transfecting knockdown cells with a knock-in vector containing an shRNA-refractive cDNA that will express the protein of interest even in the presence of shRNAs. The constructed knockdown and knock-in vectors can be easily used concurrently to assess possible interrelationships between genes, the effects of gene loss on cell function and/or their restoration by replacing targeted genes one at a time. The entire knockdown/knock-in procedure can be completed in approximately 3–4 months.

Keywords: gene replacement, RNA interference (RNAi), multiple knockdown, U6 promoter

INTRODUCTION

One of the major advances in studying protein function in the last few years has been the use of RNAi technology to target the knockdown of specific mRNAs1,2. However, this technology has several limitations. For example, one restriction has been that this procedure has been used largely to target the removal of mRNA encoding a single protein. Several laboratories, including ours, have recently developed procedures for simultaneous targeted removal of two or more genes in various organisms, thereby expanding the usefulness of RNAi technology as a tool for studying protein function. These advances have been made through the development of vectors that allow the insertion of multiple shRNA encoding sequences3–10; these vectors have been used to simultaneously target a variety of genes3, 4, 6–8. As efficient knockdown of some mRNAs has been difficult to achieve, several of the shRNA vectors have also been used to target multiple sites within a single mRNA to maximize knockdown efficiency3, 5–7, 9, 10. Thus, these shRNA vectors have been used to target either multiple genes or multiple sites within one gene in a number of organisms, including mammals3, 6, 7. Although vectors similar to the one we have developed have also been used in mammals by other investigators3–7, 9, 10, our vector has the advantage that it has been specifically designed to facilitate the repeated insertion of multiple shRNA cassettes3. Furthermore, the strategy described in this protocol can be used to modify other vectors with different promoters (e.g., H1 or 7SK, etc.); and by making the restriction enzyme sites of these promoter-shRNA cassettes from different vectors compatible with each other, efficient combination of multiple cassettes with different promoters can be achieved.

Another important constraint in RNAi technology has been that it was designed to study only the effects of the loss of the targeted protein, precluding a comprehensive analysis of overall protein function. Several gene replacement strategies for restoring protein expression have been developed in mammalian and numerous other systems that circumvent the RNAi knockdown vector. These strategies include the use of silent mutations (i.e., degenerative codon nucleotides) in the knock-in vector that bypass the targeting vector11–15, species variations in the shRNA targeted region between the host gene and the knock-in homologous genes11, 16, simultaneous microinjection of knockdown/knock-in RNAs into Xenopus oocytes15 and other similar strategies. One strategy, termed “differential RNA interference”, involves targeting the 3'-untranslated region (3'-UTR) of wild type mRNA with the simultaneous expression of a vector containing only the coding region of the targeted gene. 17 We previously used a similar strategy for studying the function of selenium-containing proteins (selenoproteins) by targeting the 3'-UTR18 that contains the essential SECIS element which dictates selenocysteine insertion in response to the UGA termination codon19. Since the SECIS element is required for translation of selenoprotein mRNA, shRNAs were designed to target other regions within the 3'-UTR and mutations were made in the knock-in vector to circumvent shRNA targeting, rather than deleting the entire 3'-UTR18.

All of the above gene replacement strategies are based on modification of the shRNA-targeted region to efficiently re-express recombinant genes. The most commonly used strategy involves generating silent mutations in the coding regions11–15. However, a limitation of this method is that the silent mutations may affect the expression of the recombinant genes20. Knock-in of homologous genes11, 16 is an alternative method to bypass shRNA targeting, though it is limited by the availability of such genes. In addition, some homologous genes may not have an identical function to the shRNA-targeted gene(s)11. Targeting the 3'-UTR has been shown to be as effective as targeting the coding region21, 22, and should work on any gene provided the targeted gene contains a suitable target region. This method provides greater flexibility in re-expressing the recombinant genes.

This protocol describes the design and modification of novel shRNA vectors for knockdown of multiple genes, permits testing of the knockdown efficiency of each shRNA and allows for easier combination of the most efficient promoter-shRNA cassettes from different genes without constructing additional shRNA vectors. In addition, the strategy for re-expressing one or more recombinant genes has been introduced for the purpose of either confirming the on-targeting effects (i.e., that the observed phenotypes are the result of shRNA-induced effects on the targeted gene and not due to effects on non-targeted genes) of the shRNA knockdown or analyzing the function of modified recombinant genes.

Overview of the Procedure

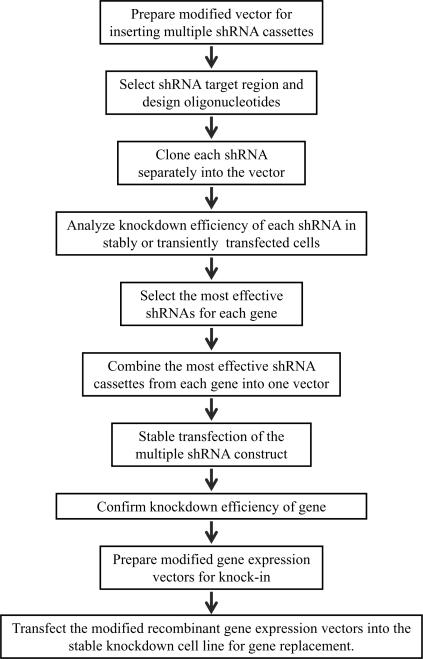

To facilitate the use of our protocol, an overview of the entire procedure is shown in Figure 1. Construction of the vectors used in the protocol is discussed below. For stable and simultaneous knockdown of multiple genes, it is highly recommended to insert all of the shRNAs into a single vector for easier transfection of cells. A shRNA vector must be designed and constructed to allow for easier and repetitive insertion of multiple shRNAs. In this protocol, a U6 promoter-containing vector (pSilencer 2.1 U6 Hygro) is modified for this purpose. After selecting a shRNA target region and synthesizing oligonucleotides, each shRNA is cloned into this modified vector individually to add the U6 promoter. Following digestion of the cloned shRNA and isolation of the resulting U6-shRNA cassette, cassettes can then be inserted in tandem. Either stable transfection or transient transfection can be used to evaluate knockdown efficiency and off-targeting effects of each individual shRNA before combining multiple shRNAs into a single vector. The advantage of using transient transfection to monitor knockdown efficiency is that it requires only 2–3 days to determine efficiency, whereas stable transfection may take 3–4 weeks. However, the efficiency of transient transfection can vary from cell type to cell type and cannot be used with every cell line to assess whether knockdown has occurred in which case stable transfection would be required to be conclusive. If two or more effective shRNAs from one gene generate the same phenotype, this result can be considered an on-targeting effect. If the shRNA targeted sequences are available in a public siRNA database (e.g., http://www.rnainterference.org), or have been previously identified and characterized, these evaluation steps may be omitted. After evaluating the knockdown effects of each shRNA, the most effective shRNAs from each gene can be combined for targeting multiple genes simultaneously. Finally, after generating a stable cell line with multiple shRNAs and confirming the knockdown efficiency of each gene, the cell line can be transfected with the gene replacement vector, containing the modified target gene that it no longer contains target sites for the shRNAs.

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the procedure

Advantages and Limitations of the Method

Development of a construct encoding multiple shRNAs targeting genes for their simultaneous removal expands the usefulness of the already established powerful tool of RNAi technology. It provides a simple, rapid and effective means of generating stably transfected, multiple knockdown shRNA cell lines. Furthermore, this approach permits us to target a variety of genes to elucidate their possible interplay and/or their loss on cell function and broadens our approaches in therapeutic strategies. Alternatively, the multiple shRNA targeting vector can be used to target multiple sites within a single mRNA in the event no one site may effectively knockdown protein expression.

When an investigator wishes to over-express a specific gene by introducing the corresponding recombinant gene, the interpretation of the resulting over-expression is often hampered by the interference of endogenous mRNA expression. Unless cell lines from naturally occurring mutations or knockout mice are available that remove expression of the endogenous gene, it otherwise may be difficult and time-consuming to remove endogenous gene expression. Multiple shRNAs can be used to selectively suppress endogenous gene expression without affecting the expression of a transfected, recombinant version of the same protein. The fact that we can also replace gene expression either individually or collectively provides an alternative means of assessing the interplay of different proteins as well as their individual or collective effect on overall cellular function11–15, 18, 23. The recovery of gene function by re-expression of the recombinant gene(s) can also be used as a means of excluding possible off-targeting effects of the shRNA knockdown11, 16.

One limitation of shRNA technology is that it can be difficult to completely knockdown the expression of a gene. In most cases, a low expression level of targeted endogenous genes remains; and this low level of expression may still be adequate for gene function affecting the interpretation of re-expression of the corresponding recombinant gene. In such cases, it may be necessary to generate a cell line from knockout mice in order to study the function of the gene under investigation.

Experimental Design

Choice of promoter for the shRNA vector

In this protocol, we elected to use the pSilencer 2.1 U6 Hygro vector as the backbone to generate a multiple shRNA vector. The U6 and H1 promoters are commonly used for expressing shRNA since they have a well defined start and stop signal with all required regulatory elements located immediately upstream of the transcripted sequence, which makes it easy to manipulate for direct expression of shRNA24, 25. The U6 vector is used herein since it has been shown to be more efficient than the H1 promoter in expressing shRNA26, 27. The efficiency of the 7SK promoter is comparable to the efficiency of U6 promoters28–30. Other RNA Polymerase III promoters, such as 5S, 7L and tRNA promoters, have also been used to drive shRNAs24, 25, 31, 32. It should be noted that the highly expressed U6 promoter may cause greater cell toxicity than other promoters26, 33, whereas shRNA vectors with a different promoter, such as H1 and tRNA promoters, may cause less toxicity and can be used as alternatives25, 26, 31. However, since the control cells are also transfected with the same vector, toxicity due to the vector should be similar between control and targeted cells. In the event a vector with a different promoter is employed, the restriction enzyme sites used for modification and cloning will be different and appropriate changes to accommodate these restriction sites will be necessary.

For transfection of primary cells or other difficult-to-transfect cells, a lentiviral or a retroviral vector can be used. In this case, each shRNA should be driven by different promoters (e.g., U6, H1, 7SK, 5S, 7L or tRNA promoters)7, 10, 24, 25, 31, 32 to avoid deletions of shRNA cassettes due to recombination of repeat promoter sequences during transduction of the viral vector34. The number of shRNAs that can be combined in one vector will be limited by the number of promoters available.

Modification of shRNA vectors to enable cloning of multiple shRNAs

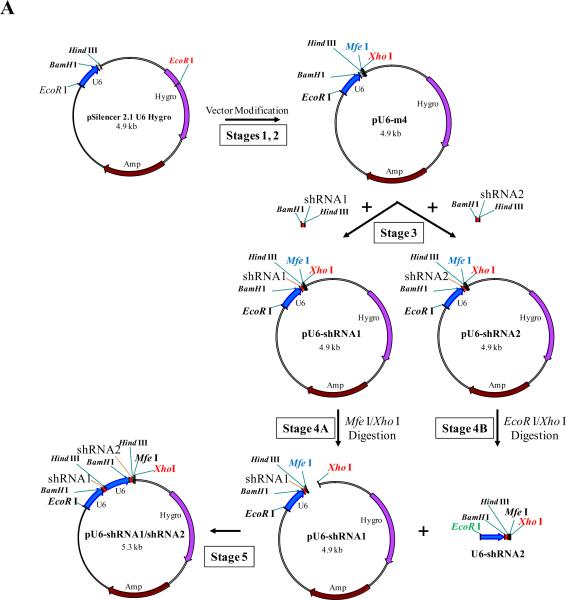

The EcoR I sites at position 4110 in the pSilencer 2.1 U6 Hygro vector should initially be removed to generate a single EcoR I site immediately upstream of the U6 promoter (see Figure 2A, Step 1). The primers (EcoR-Mut-F and EcoR-Mut-R) used for changing the EcoR I site at position 4110 are shown in Table 1 wherein the red letters represent the EcoR I site to be mutated. Then, Mfe I (position 384) and Xho I (position 393) sites can be added downstream of the U6 shRNA cassette as shown in Figure 2A, Step 2. The primers (Mfe-Xho-Mut-F and Mfe-Xho-Mut-R) used for mutagenesis are also shown in Table 1 (the red letters represent the enzyme sites to be added).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of cloning tandem, multi-shRNA sequences. In A), the original pSilencer 2.1 U6 Hygro vector is initially modified in two stages to generate pU6-m4: in Stage 1, a mutation is made in EcoR 1 to remove this endonuclease restriction site; in Stage 2, mutations are introduced immediately downstream of the Hind III site to produce Mfe I and Xho I sites. In Stage 3, an annealed shRNA dsDNA fragment, designated shRNA1, is then cloned into pU6-m4 at the BamH I and Hind III sites to produce the pU6-shRNA1 vector and a second annealed shRNA dsDNA fragement, designated shRNA2, is cloned separately into pU6-m4 at the BamH I/Hind III sites to produce a second pU6-shRNA vector designated pU6-shRNA2. Other annealed shRNA dsDNA fragments (e.g. shRNA3, shRNA4, etc.) can also be cloned in the same manner. In Stage 4A, one of the pU6-shRNA constructs, e.g., U6-shRNA1, is selected as the backbone for adding additional shRNA cassettes and is digested with Mfe I/Xho I. In Stage 4B, one of the separately prepared U6-shRNA vectors is digested with EcoR I/Xho I to yield a 400 bp, shRNA fragment (designated U6-shRNA2) with an EcoR I site at the U6 promoter 5' end and a Xho I site at the 3' end, which is cloned into the Mfe I and Xho I sites of the pU6-shRNA1 construct (Stage 5) to generate the 5.3 kb pU6-shRNA1/shRNA2 construct. As noted in the text, additional shRNA units can then be individually added to the pU6-shRNA using the same strategy. In B, the sequences of the Mfe I and EcoR I sites are given showing that they have compatible cohesive ends, but following ligation, the newly generated site cannot be re-cut by either endonuclease.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide sequences.

| Oligo name | Sequences | Modification | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| EcoR-Mut-F | 5'- GGC TCT CGC TGA ACT CCC CAA TGT CA-3' | None | Forward primer for removing the EcoR I site at position 4110 in the pSilencer 2.1 U6 Hygro vector. |

| EcoR-Mut-R | 5'- TGA CAT TGG GGA GTT CAG CGA GAG CC -3' | None | Reverse primer for removing the EcoR I site at position 4110 in the pSilencer 2.1 U6 Hygro vector. |

| Mfe-Xho-Mut-F | 5'-CGT TGT AAC TCG AGG GCC AAT TGT GCC AAG CT-3' | None | Forward primer for adding Mfe I ( at position 384) and Xho I (at position 393) sites to the pSilencer 2.1 U6 Hygro vector. |

| Mfe-Xho-Mut-R | 5'-AGC TTG GCA CAA TTG GCC CTC GAG TTA CAA CG-3' | None | Reverse primer for adding Mfe I ( at position 384) and Xho I (at position 393) sites to the pSilencer 2.1 U6 Hygro vector. |

| shRNA-F | 5'- GATCC X1919–21* TTC AAG AGA X19–21* T TTT TTG GAA A-3' | None | Forward oligonucleotide for generating shRNA insert for cloning into the pU6-m4 vector. |

| shRNA-R | 5'- AGC TTT TCC AAA AAA X19–21* TCTCTTCAA X19–21* G -3' | None | Reverse oligonucleotide for generating shRNA insert for cloning into the pU6-m4 vector. |

| Rev2.0 | 5'- AGG CGA TTA AGT TGG GTA-3' | None | For sequencing shRNA constructs. |

X19–21 represents either sense (shown in blue) or antisense (shown in red) sequences of targeted regions (see Figure 3A)

Mfe I and EcoR I have matched ends which can be ligated to each other, but cannot be re-cut by either endonuclease after ligation (Figure 2B). This feature facilitates the repetitive insertion of multiple U6-shRNA cassettes into the vector3. The modified U6 vector described above (designated as pU6-m4 which is available upon request) is used for generating multiple shRNA constructs. Each shRNA oligonucleotide lacking a U6 promoter (see Figure 3A) can be individually cloned into this modified vector that contains the U6 promoter using the BamH I/Hind III sites (Figure 2A, Step 3) generating a variety of constructs, each containing different shRNAs (designated shRNA1 and shRNA2 in the figure). One of the constructs (designated pU6-shRNA1) is selected as the backbone for adding additional U6-shRNAs and it can then be cut with Mfe I/Xho I restriction enzymes (designated Step 4A). Another U6-shRNA construct (designated U6-shRNA2) is cut with EcoR I/Xho I to generate a U6-shRNA cassette (designated U6-shRNA2, Step 4B) which in turn can be inserted into Mfe I/EcoR I sites (Step 5) to yield the pU6-shRNA1/shRNA2 construct. The latter construct is then used to insert additional U6-shRNA cassettes by repeating Steps 4a, 4B and 5.

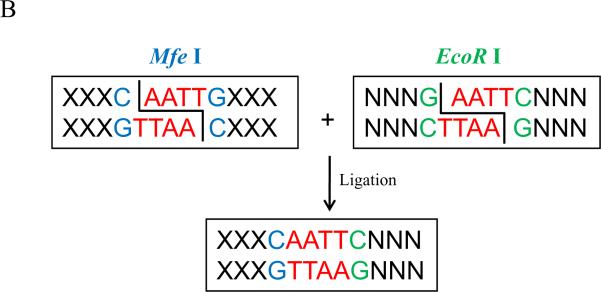

Figure 3.

Design of shRNA oligonucleotides for knocking down gene expression and silent mutations for knocking-in gene expression at internal gene regions. In A), annealed shRNA oligonucleotides form dsDNA fragment with BamH I/Hind III sites, respectively (shown by green letters) at the ends. In B), the hairpin structure of shRNA that is formed after the complimentary fragments are transcribed from the shRNA vector in cells. In C), an example of forward primers used for modifying knock-in genes on the shRNA targeted site. The red letters indicate the targeted sequences and the blue letters show the mutations in several wobble positions.

The above strategy for modifying vectors and inserting shRNAs can also be used to modify vectors with different shRNA promoters (e.g. U6, H1, 7SK, 5S, 7L, and tRNA promoters). Each shRNA can be inserted into one of the modified vectors separately, and then, the different shRNA cassettes with different promoters will possess compatible restriction enzyme sites (e.g., EcoR I/Mfe I) and can easily be combined in one vector. This alternative cloning strategy is very useful when viral vectors are used (see “Choice of promoter for the shRNA vector”).

shRNA design

The strategy for choosing shRNA target sites is based on previously published observations35, 36. Selecting 21–23 nt sequences in the target mRNA that begin with an AA dinucleotide (the targeted sequences, 19–21 nt, start right after the AA dinucleotide) as the targeted region will be ideal though sequences with other dinucleotides will work as well. The GC content of the targeted regions should be between 30–50% for proper shRNA functionality36. A nucleotide BLAST search (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) of the chosen shRNA sequences should be carried out to minimize the possibility of shRNA off-targeting effects.

There are alternative programs for choosing shRNA targeting sequences3, 11, 18, 37, for example, “siDESIGN” from Dharmacon Research, Inc. (http://www.dharmacon.com/DesignCenter/DesignCenterPage.aspx), “BLOCK-iT™ RNAi Designer” from Invitrogen (https://rnaidesigner.invitrogen.com/rnaiexpress/), “siRNA Target Finder” from Ambion (http://www.ambion.com/techlib/misc/siRNA_finder.html), or other similar programs. Some of the above programs, like “siDESIGN” of Dharmacon, can also help to select shRNA with an optimal seed region38,39 to reduce unwanted cellular effects and avoid antisense strand-mediated off-targeting effects (see below for further control of off-targeting).

Forward and reverse chains of oligonucleotides containing 19–21 nucleotides of sense and 19–21 nucleotides of antisense targeting sequences with an intervening TTCAAGAGA spacer should be synthesized. The sequence TTCAAGAGA is a spacer used in the original pSilencer 2.1 U6 Hygro vector which aids the transcribed shRNA in forming a hairpin structure. A model pair of oligonucleotide sequences, designated shRNA-F and shRNA-R, is shown in Table 1, where “X” represents the sense (shown in blue) and anti-sense (shown in red) targeting sequences of the shRNA. Several extra nucleotides (shown in green) should be added to generate BamH I and Hind III restriction enzyme sites on the annealed dsDNA fragment (see Table 1). The forward and reverse chains of oligonucleotides are annealed to form a dsDNA fragment with BamH I and Hind III sites for inserting into pU6-m4 (see Figure 3A). The transcribed shRNA will form a hairpin structure with an intervening TTCAAGAGA loop as shown in Figure 3B.

Four to five shRNA target sequences should be chosen and the corresponding annealed dsDNA fragments can be cloned into the modified U6 vector, pU6-m4, as described above and in Steps 9–18 below.

Controlling for off-target effects and cell toxicity

To evaluate off-targeting effects40, two different combinations of effective shRNAs from each gene can be tested separately (see “Anticipated Results” for detail). Since off-targeting is sequence dependent, then, if vectors with different U6-shRNA combinations from the same genes show the same phenotype after transfection, the possibility that the observed phenotype is a result of off-targeting is substantially reduced. If different phenotypes are observed with different shRNAs targeting the same gene, and reduction in the targeted mRNA is the same, this result is almost certainly due to off-targeting, and more shRNAs targeting different regions should be tested. Alternatively, knock-in of the modified gene to specifically recover the lost gene function provides strong evidence that observed phenotypes are not the result of off-targeting effects of the shRNA knockdown11, 16.

shRNA-induced cell toxicity is another potential issue that needs to be addressed26, 33. shRNA cell toxicity is thought to arise from oversaturation of the shRNA pathway33, although the precise mechanism is unknown. A control vector should always be included to evaluate shRNA toxicity and to analyze loss of gene function. If cells transfected with a control vector exhibit abnormal growth or death, it is likely due to U6 promoter toxicity. In this case, another promoter, such as H1 or a tRNA promoter, can be used.

Limits on the number of shRNAs that can be inserted

Clearly, there is a maximal number of shRNAs that can be inserted into one vector since the vectors have a tendency to lose inserted large fragments (more than 10 –15 kb) during cloning. Since the U6-shRNA cascade is about 410 bp, a combination of twenty inserts should not pose a problem in cloning. We have successfully combined up to six different shRNAs from two different genes into one vector using our protocol, and efficiently knocked down both genes3.

Choice of cell line

Depending on the targeted genes, commonly used cell lines such as NIH 3T33, 11, 18, HEK 2937, 21 and HeLa cells4, 9, 10 can be chosen. Cell lines can be pre-selected to check the expression level of the targeted gene(s) by northern and/or western blot analysis. Cell lines manifesting a higher expression level of the targeted gene(s) are generally better for investigating the knockdown effects. If stable transfection is used to knockdown gene expression, the efficiency of transfection will not be a concern in selecting the cell line(s), except in the case where a primary cell line is used in which case a viral vector will be required for introduction of the shRNA sequence(s) (see section “Choice of promoter for the shRNA vector.”).

Several cell lines such as NIH 3T3, DT, TCMK, LLC-1 cells have been tested in our lab for stable knockdown of various genes3, 11, 18, 37, 41, 42. The mRNA knockdown efficiencies caused by the corresponding shRNAs varied from 50% to 98% as demonstrated by northern blotting. The knockdown efficiency depends on the shRNA target sites (see Figure 4A and 4B). Reduction in the expression of some genes due to the presence of the corresponding shRNA resulted in a dramatic effect on cell function, wherein the cells grew very poorly, with only 50% knockdown in mRNA levels (e.g., GPx4), while others reached ~90% reduction in mRNA levels before manifesting a phenotypic change (e.g., SECp43). For most genes, the knockdown efficiency of an effective shRNA should reach 80% to 90% following stable transfection.

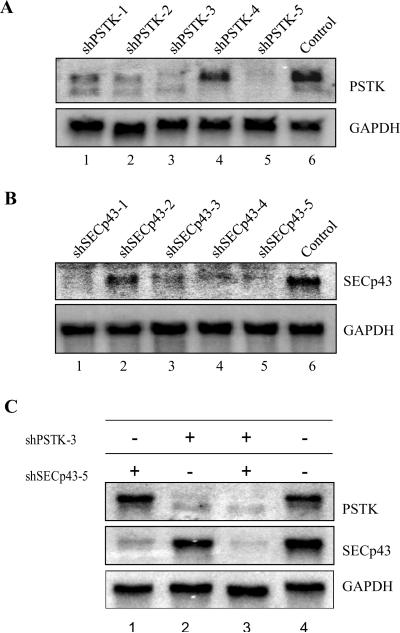

Figure 4.

Analysis of targeted mRNAs in transfected cells encoding knockdown vectors. Northern blotting of PSTK and SECp43 in shRNA transfected NIH 3T3 cells. NIH 3T3 cells were stably transfected with shRNA or control constructs, RNA extracts prepared from the resulting transfected cells, electrophoresed and transblotted onto membranes for Northern blotting as described3, 37. Densitometry was performed by PhosphorImager analysis. In A) and B), cells were transfected with control vector (lane 6) or with shRNA constructs targeting five separate regions (lanes 1–5) within the coding sequences of PSTK (A) or SECp43 (B) and the efficiency of knockdown estimated by Northern blotting. In C), cells were transfected with shRNA constructs selected from the analysis in (A and B) above (see text) for targeting PSTK or SECp43 either individually (lane 1, shSECp43–5 (chosen from lane 5 in panel B above); lane 2, shPSTK-3 (chosen from lane 3 in panel A above)), or simultaneously (lane 3) or with the control construct (lane 4). The efficiency of knockdown was: lane 1, SECp43 (83%); lane 2, PSTK (91%); and lane 3, SECp43 (91%) and PSTK (98%).

Generation of the expression vector for gene replacement(s)

To further examine the role(s) of targeted endogenous gene(s), other than assessing its (their) loss on cell function, an alternative strategy is required for replacing the knocked down gene(s), i.e., a gene replacement strategy, designed to circumvent the shRNA knockdown, is required. The aim in this strategy is to introduce a cDNA construct of the targeted gene that has been modified so that it no longer contains target sites for the shRNAs, but still encodes a functional protein. This construct should restore full function and rescue any loss-of-function phenotype. Other modifications, such as changing key amino acids and adding or deleting domains, can be also made to the genes if those are desired for gene function analysis. In the case that the 3'-UTR is targeted, the targeted region can be either deleted or individual bases mutated without affecting protein expression, or the coding region alone can be cloned into the expression vector17, 18. However, if the shRNA target region is located in the open reading frame, 4–5 mutations in the wobble positions of codons in the shRNA target region will need to be made11–15, 23 The modified gene expression vector can be transfected into the cells with shRNA knockdown of the endogenous gene(s). An example of mutating wobble bases in the 3'-position is shown in Figure 3C.

Alternatively, after the above modifications have been completed, an entire gene expression cassette (including the promoter, the coding region and the polyA signal sequences) may also be inserted into the Xho I and Mfe I sites of the shRNA constructs. In this manner, the construct will contain both knockdown and knock-in cassettes which will facilitate transfection and stabilization of gene expression in the cells. This will be especially helpful when the targeted genes are essential in which case the cells will not survive when the genes are knocked down.

MATERIALS

REAGENTS

! CAUTION For all reagents, follow manufacturer's recommendations for storage of stock solutions and materials. Wear proper safety equipment, including laboratory coat, safety glasses and appropriate gloves, for all experiments.

pSilencer 2.1 U6 Hygro vector (Ambion, cat. no. AM5760)

pcDNA3.1 expression vector (Invitrogen, cat. no. V38520)

Oligos for mutagenesis of pSilencer 2.1 U6 Hygro –as listed in Table 1 (see also Experimental Design) or user-defined if using a vector other than pSilencer 2.1 U6 Hygro (Sigma Genosys)

shRNA oligos – user-defined for specific target genes (see Experimental Design and Table 1).

Quick Ligation Kit (New England BioLabs, cat. no. M2200S)

QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, cat. no. 200523)

PfuUltra DNA polymerase kit (Stratagene, cat. no. 600380)

DMEM Cell culture medium (Gibco, cat. no. 11995)

Opti-MEM (Gibco, cat. no. 31985)

Fetal bovine serum (Gibco, cat. no. 10438)

SOC Medium (Invitrogen, cat. no. 15544-034)

LB Broth Plates with 100 μg/ml Ampicillin (KD Medical, cat. no. BPL-2200)

LB Broth (KD Medical, cat. no. BLF7030)

Ultrapure water (KD Medical, cat. no. RGF-3410)

Ampicillin (Sigma, cat. no. A-0166)

Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, cat. no. 11668)

TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, cat. no. a5596-018). ! CAUTION Irritant to eyes and skin, handle with care.

Hygromycin B (Cellgro, cat. no. 30-240-CR)

Hind III, EcoR I, Xho I, Mfe I, BamH I, Dpn I (New England BioLabs, cat. no. R0104S, R0101S, R0146S, R0589S, R0136S, R0176S, respectively) or other suitable restriction enzymes.

QIAprep Spin Miniprep Plasmid Preparation Kit (Qiagen, cat. no. 27104)

QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, cat. no. 28704)

6× DNA loading buffer (Quality Biological, Inc., cat. no. 351-028-031)

Agarose (Invitrogen, cat. no. 15510)

50× TAE buffer (Quality Biological, Inc, cat. No. 351-008-131)

NuPAGE Novex 4–12% Bis-Tris Gels (Invitrogen, cat. no. NP0322)

10 mg/ ml Ethidium bromide (Invitrogen, cat. no. 15885) ! CAUTION Strong mutagen, handle with care.

GC5 high efficient competent E. coli cells (Gene Choice, cat. no. 62-7000-12)

NIH 3T3 cells (ATCC, cat. no. CRL-1658), or other cell lines

REAGENT SETUP

50 mg/ml Ampicillin Prepare 50 mg/ml Ampicillin, store at −20°C up to 1 year.

DMEM Medium Add 10% FBS to DMEM medium, store at 4°C up to 1 month.

1% Agarose gel Put 1.0 g of Agarose powder in 98 ml H2O and melt the agarose in a boiling water bath, add 2 ml of 50× TAE buffer and 10 μl of 10 mg/ml ethidium bromide, cool it down to about 60°C and pour proper amount to the gel tanks. The cast agarose gels can be then left at room temperature (25°C) up to 8 hours before use.

EQUIPMENT

Thermal cycler PCR system (Perkin Elmer).

Gel-electrophoresis apparatus. Most commercially available gel electrophoresis systems for agarose gels are suitable.

Electrophoresis power supply. Most commercial power supplies sold for SDS-PAGE or DNA-sequencing applications are suitable.

Bacterial cell incubator. Most commercially available bacterial incubators are suitable.

Mammalian cell incubator. Most commercially available CO2 cell incubators for growing mammalian cells are suitable.

Spectrophotometer: Hewlett Packard 8453 System

-

UV transilluminator. Most commercially available UV lamps for DNA gels are suitable.

! CAUTION Harmful to eyes and skin, wear suitable protective gear.

Autoradiography film cassette and Kodak BioMax MR films (Kodak, cat. no.8952855) or cassette and storage phosphor screen.

Access to a darkroom equipped with film developer is needed for film autoradiography.

Access to a PhosphorImager (GE Healthcare) instrument is needed for phosphor screen imaging.

PROCEDURE

Mutagenesis of pSilencer 2.1 U6 Hygro vector ●TIMING 1 –2 weeks

- 1. Prepare the following reaction mix for one set of primers in a 0.2 ml thin-wall PCR tube using Ultra Pfu DNA polymerase. (Alternatively, a QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit may be purchased and the manufacturer's instructions followed):

Component Volume per reaction (μl) Final concentration or amount 10× PCR reaction buffer 5 μl 1× dsDNA plasmid (variable concentration) variable 5–50 ng forward primer (20 μM) 1.0 μl 0.4 μM reverse primer (20 μM) 1.0 μl 0.4 μM dNTP mix (10 mM each) 1.0 μl 0.2 mM UltraPfu DNA polymerase (2.5 units/ μl) 1.0 μl 2.5 units ddH2O variable final volume to 50 μl - 2. Place all tube(s) in a thermal cycler, and run a PCR using the following cycling conditions:

Cycle number Denature Anneal Extend 1–20 95°C 20 sec 55°C 20 sec 68°C 1 min/kb of plasmid length 21 10 min at 72°C -

3. After PCR, add 10 units of Dpn I into the PCR reaction tube and incubate at 37°C for 1 h. The Dpn I will only digest and eliminate the plasmid template.

■ PAUSE POINT Can be left overnight at 4°C or stored frozen for up to one month at −20°C.

4. Use 2 μl of Dpn I-treated DNA from step 3 to transform GC5 high efficiency competent E. coli cells and plate on 50ug/ml Ampicillin LB plates following the manufacturer's instructions, and then incubate at 37°C overnight.

5. Choose 2–3 colonies, and use each to individually inoculate 5 ml of LB broth supplemented with 100 μg/ml of Ampicillin. Grow overnight at 37°C in a shaking incubator at 250 rpm.

6. Next day, extract each plasmid using a Qiagen MiniPrep plasmid preparation kit (according to the manufacturer's instructions).

-

7. Sequence the plasmids using primer Rev2.0 (see Table 1) to confirm only the desired mutations have been generated.

▲ CRITICAL STEP The mutations should be confirmed by sequencing before proceeding to the next step.

8. Repeat steps 1–7 to generate the other necessary mutations by using the plasmid generated in step 7 as a template.

Generating single shRNA constructs.●TIMING 1–3 weeks

-

9. For each shRNA, set up the reaction tabulated below to anneal the corresponding forward and reverse shRNA oligonucleotides. Heat the mix to 95°C for 5 min, and then let it cool slowly at room temperature (25°C).

Component Volume per reaction (μl) Final concentration or amount forward oligonucleotide (1.0 mg/ml) 1.0 μl 1.0 μg reverse oligonucleotide (1.0 mg/ml) 1.0 μl 1.0 μg 1× TE buffer 18 μl 18 μl ■ PAUSE POINT The annealed oligonucleotides can be used at this point for ligation or can be stored frozen at −20°C up to one month.

-

10. Digest the modified shRNA vector from step 8 with BamH I and Hind III, as tabulated below. Incubate at 37°C for 1 h.

Component Volume per reaction (μl) Final concentration or amount 10× reaction buffer 5 μl 1 × reaction buffer vector plasmid from step 8 (variable concentration) variable 1–5 μg each restriction enzyme variable 2–5 units/ μg of DNA (10–20 × 103 units/ml) ddH2O variable To a final volume of 50 μl ▲ CRITICAL STEP Do not use the MfeI and Xho I sites for inserting the shRNA targeting sequences. These two sites will be used to combine multiple shRNA cassettes into one vector.

11. Add 10 μl of 6× DNA loading buffer and load onto a 1% (wt/vol) agarose gel with 1 μg/ ml of ethidium bromide and run in 1× TAE buffer at 100v about 30 min to allow the leading dye reach 2/3 of the gel length.

12. Excise the band corresponding to the full-length vector (4.9 kb in the case of pU6-m4) under 360 nm UV light with a scalpel. Only one prominent band should be visible in the gel.

-

13. Use a Qiagen QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit to recover the digested plasmid from the gel and elute in 30 μl of elution buffer. Use 5 μl to measure the DNA concentration using a spectrophotometer.

■ PAUSE POINT This purified fragment can be used immediately for ligation or can be stored at −20°C up to one month.

-

14. Individually ligate each annealed oligonucleotide mix (from step 9) into the modified shRNA vector digested with BamH I and Hind III (from step 13) using a Quick Ligation Kit: set up a separate reaction mix for each shRNA as tabulated below and allow the ligation reaction to proceed at room temperature for 10 min.

Component Volume per reaction (μl) Final concentration or amount 2× Ligation buffer 10 μl 1 × reaction buffer annealed oligonucleotides mix from step 9 (0.1 mg/ml) 1 μl 100 ng BamH I and Hind III digested shRNA vector from step 13 (variable concentration) variable 50 ng Quick Ligase (2.0 × 106 units/ml) 1.0 μl 2,000 units ddH2O variable To a final volume of 20 μl ■ PAUSE POINT The ligation reactions can be used immediately for transformation or can be stored frozen for up to one week at −20°C.

15. Use 2 μl of each ligation reaction from step 14 to transform GC5 high efficiency competent E. coli cells and plate on 50ug/ml Ampicillin LB plates following the manufacturer's instructions, and then incubate at 37°C overnight.

16. Choose 2–3 colonies for each ligation, and use them to individually inoculate 5 ml of LB broth supplemented with 100 μg/ml of Ampicillin. Grow overnight at 37°C in a shaking incubator at 250 rpm.

17. Extract each plasmid using a Qiagen MiniPrep plasmid preparation kit, according to the manufacturer's instructions.

-

18. Sequence the plasmids using primer Rev2.0 (see Table 1) to confirm that the generated shRNA vectors have the correct sequence.

▲ CRITICAL STEP Confirm each shRNA sequence before proceeding to the next step.

Evaluating the knockdown efficiency of each shRNA.●TIMING3–6 weeks

-

19. Culture NIH 3T3 cells in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum at 37°C in a CO2 incubator before transfection. If another cell line is selected for use, the appropriate culture medium and growth conditions should be used.

▲CRITICAL STEP A control vector, which has the similar nucleotide composition as the shRNA but lacks significant sequence homology to the genome, should always be included to evaluate shRNA toxicity and the effect of loss of gene function.

20. One day prior to transfection, plate 5 × 105 cells in one well of a 6-well plate with 2 ml of growth medium without antibiotics so that cells are 90–95% confluent at the time of transfection. One well of cells is needed for each shRNA construct to be tested.

21. Transfect cells using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer's instructions.

22. Incubate cells at 37°C in a CO2 incubator. Medium may be changed after 4–6 h.

23. Passage cells 1:5 into fresh growth medium 24 h after transfection at 37°C in a CO2 incubator. Optionally, 48–96 h after transfection, use 1 × 106 of the cells to check the removal of targeted genes using northern blotting43 and/or western blotting (http://www.e-biotek.com/protein/244-western-blot-protocol.html).

-

24. Add selective medium with hygromycin B (or appropriate antibiotic[s]) on the following day. Treat cells with antibiotics for 2–3 weeks to stabilize the transfection at 37°C in a CO2 incubator. 1 × 106 of the cells can be used to check the removal of targeted genes using northern43 and/or western blotting (http://www.e-biotek.com/protein/244-western-blot-protocol.html).

▲CRITICAL STEP The knockdown efficiency can be evaluated by transient (Step 23) or stable (step 24) transfection bearing in mind the restrictions and advantages of both means of monitoring knockdown efficiency discussed in Experimental Design.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

Combining multiple U6-shRNA cassettes into one vector.●TIMING1–5 weeks

- 25. Digest one of the shRNA constructs with Xho I and Mfe I (this will provide the `vector') and digest another shRNA construct with Xho I and EcoR I (this will provide the shRNA `insert'), as tabulated below. Incubate at 37°C for 1 h.

Component Volume per reaction (μl) Final concentration or amount 10× reaction buffer 5 μl 1 × reaction buffer plasmid from step 18 (variable concentration) variable 1–5 μg each restriction enzyme (10–20 μ 103 units/ml) variable 2–5 units/ μg of DNA ddH2O variable To a final volume of 50 μl 26. Add 10 μl of 6× DNA loading buffer and load onto a 1% (wt/vol) agarose gel with 1 μg/ ml of ethidium bromide and run in 1× TAE buffer at 100v about 30 min to allow the leading dye reach 2/3 of the gel length.

-

27. Excise the band corresponding to the 4.9 kb vector from Xho I and Mfe I digested reaction, and the 400 bp U6-shRNA fragment from Xho I and EcoR I digested reaction under a 360 nm UV light with a scalpel.

▲CRITICAL STEP There should be only one 4.9 kb band visible in the gel for Xho I and Mfe I digested plasmid . Recover this band. The Xho I and EcoR I digested plasmid will show two bands (4.5 kb and 400bp) in the gel. Be sure to recover the U6-shRNA band (400 bp) from the gel.

-

28. Use a Qiagen QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit to recover the digested plasmid from the gel and elute in 30 μl of elution buffer. Use 5 μl to measure the DNA concentration using a spectrophotometer.

■PAUSE POINT This purified fragments can be used immediately for ligation or can be stored at −20°C up to one month.

-

29. Ligate the purified vector and the shRNA insert (from step 28) using a Quick Ligation Kit, as tabulated below. Let the ligation reaction proceed at room temperature for 10 min.

Component Volume per reaction (μl) Final concentration or amount 2× Ligation buffer 10 μl 1 × reaction buffer Xho I and Mfe I digested vector from step 28 (variable concentration) variable 50 ng Xho I and EcoR I fragment from step 28 (variable concentration) variable 50 ng Quick Ligase (2.0 × 106 units/ml) 1.0 μl 2,000 units ddH2O variable To a final volume of 20 μl ■PAUSE POINT The ligation solution can be used immediately for transformation or can be stored frozen for up to one week at −20°C.

30. Use 2 ul of ligated DNA from step 29 to transform GC5 high efficiency competent E. coli and plate on 50ug/ml Ampicillin LB plates following the manufacturer's instructions, and then incubate at 37°C overnight.

31. Choose 2–3 colonies, and use each to individually inoculate 5 ml of LB broth supplemented with 100 μg/ml of Ampicillin. Grow overnight at 37°C in a shaking incubator at 250 rpm.

32. Extract each plasmid using a Qiagen MiniPrep plasmid preparation kit (according to the manufacturer's instructions).

-

33. Sequence the plasmids using primer Rev2.0 (see Table 1) to confirm the U6-shRNA fragments have been inserted into the correct position of vectors.

▲CRITICAL STEP Confirm each shRNA sequence before proceeding to the next step.

34. If more genes are to be targeted, repeat steps 25–33 to combine more U6-shRNA cassettes into one vector. The plasmid created in step 33 should be used as the `vector' in subsequent cloning rounds.

35. To evaluate off-targeting effects, generate another construct with different shRNA combinations of multiple genes by repeating steps 25–34.

Generating expression vector for gene replacement(s).●TIMING2–3 weeks

36. Clone the cDNA of your gene into a mammalian cell expression vector of your choice using any routine cloning procedure.

37. Use steps 1–7 to generate appropriate mutations in the shRNA target region of each cDNA to prevent targeting by shRNA (see Experimental Design). Once the sequence has been confirmed, this expression construct can be used for gene replacement studies. Optionally, these knock-in cassettes (if appropriately designed) can be subcloned into the XhoI/MfeI sites of the expression vector containing the knockdown (shRNA) cassette created in step 34. This will allow for faster transfection and stabilization of cells.

Transfecting cells and gene function analysis ●TIMINGAt least 3–6 weeks

38. If separate knockdown and knock-in constructs are used, proceed as described in option A. If a single knockdown/knock-in construct is used, proceed as described in option B.

Option A: Separate knockdown/knock-in vectors

-

Follow steps 19–24 to stably transfect the vector containing multiple shRNA (from step 34) into NIH 3T3 cells. Use northern blotting43 and/or western blotting (http://www.e-biotek.com/protein/244-western-blot-protocol.html) to confirm the removal of targeted multiple genes. Analysis of loss of function of targeted genes can be performed at this step.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

Repeat steps 19–23 to transfect the stable cell lines generated in step 38A–i with the corresponding expression vector(s) (from step 37) for gene replacement. 18–48 h after the transfection, the cells will be available for gene replacement and functional analysis. Depending on the genes analyzed, western blot (http://www.e-biotek.com/protein/244-western-blot-protocol.html) or specific enzyme assays can be used for functional analyses.

-

If a stable transfection is desired, treat cells with appropriate antibiotics for 2–3 weeks to obtain stably transfected cell lines.

▲ CRITICAL STEP It is necessary to use an expression vector with a different selection marker than the shRNA vector.

Option B: Single knockdown/knock-in vector

If vectors that contain both knockdown and knock-in cassettes are used, follow steps 19–23 transfect the vector (from step 37) into NIH 3T3 cells. 18–48 h after the transfection, the cells will be available for gene replacement and functional analysis. Depending on the genes analyzed, western blot (http://www.e-biotek.com/protein/244-western-blot-protocol.html) or specific enzyme assays can be used for functional analyses.

If a stable transfection is desired, treat cells with appropriate antibiotics for 2–3 weeks to obtain stably transfected cell lines.

● TIMING

Steps 1–8, Modifying the pSilencer 2.1 U6 Hygro vector: 1–2 weeks

Steps 9–18, Generating single shRNA constructs: 1–3 weeks

Steps 19–24, Evaluating the knockdown efficiency of each shRNA: 3–6 weeks Steps

25–35: Combining multiple U6-shRNA cassettes into one vector: 1–5 weeks Steps

36–37, Generating expression vector for gene replacement(s): 2–3 weeks Steps

38, Transfecting cells and gene function analysis: at least 3–6 weeks

? TROUBLESHOOTING

Troubleshooting advice can be found in Table 1.

ANTICIPATED RESULTS

The northern blot results of shRNA transfected NIH 3T3 cells are shown in Figure 4. Figure 4A and 4B show the knockdown efficiency of each single shRNA targeting SECp43 which is involved in selenoprotein synthesis3, 44 or PSTK which phosphorylates the seryl moiety on seryl-tRNA[Ser]Sec and generates an intermediate in selenocysteine synthesis45, 46. The range of knockdown efficiency varies from 40% to 98% depending on the targeting sites. The most efficient shRNA can be selected, e.g. lanes 1 or 5 for SECp43 (shSECp43-1 and shSECp43-5) and lanes 3 or 5 for PSTK (shPSTK-3 and shPSTK-5). Two different shRNA combinations of SECp43 and PSTK can be generated by joining shSECp43-1 and shPSTK-5, or shSECp43-5 and shPSTK-3. Figure 4C shows that SECp43 and PSTK were both simultaneously and efficiently removed using a shPSTK-3/shSECp43-5 double knockdown construct in which the two shRNAs are connected in tandem (Lane 3).

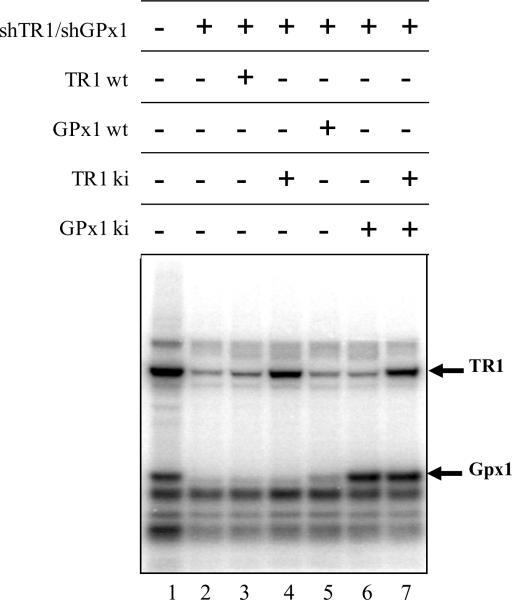

The selenoproteins, thioredoxin reductase 1 (TR1) and glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPx1), were simultaneously targeted for removal by stably transfecting DT cells, which are k-ras expressing cells derived from NIH 3T3 cells42, with a shTR1/shGPx1 double knockdown construct. The cells were then transiently transfected with either the knock-in construct that individually or simultaneously circumvented the targeting vector resulting in re-expression of one or both knocked down selenoproteins. All DT cells were labeled with 75Se to monitor selenoprotein expression and the resulting labeled selenoproteins analyzed following electrophoresis of cell extracts. The expression of selenoproteins in cells stably transfected with the control vector, pU6, is shown in lane 1 of the figure. Both TR1 and GPx1 were effectively removed by the double targeting vector (lane 2). Re-introduction of the TR1 or GPx1 wild type genes did not result in expression of these proteins due to the presence of the corresponding shRNAs generated from the stably transfected vector (lanes 3 and 5), but these proteins were expressed in cells transiently transfected with the vectors carrying TR1 and/or GPx1 genes with mutations in the regions corresponding to the shRNAs in order to circumvent the targeting regions (i.e., defined as ki [knock-in] genes in the figure, see lanes 4, 6, 7).

Figure 5.

Autoradiogram of 75Se-labeled selenoproteins in double knockdown/knock-in cells. NIH 3T3 cells that had been transformed with mutant k-ras (designated DT cells) were stably transfected with the shTR1/shGPx1 double knockdown construct or the pU6 control construct. The stably transfected, double knockdown cells were then transiently transfected with expression vectors encoding either pcDNA3.1 control (lane 2), wild type TR1 gene (TR1 wt; lane 3), TR1 knock-in gene (TR1 ki; lane 4), wild type GPx1 gene (GPx1 wt; lane 5)), GPx1 knock-in gene (GPx1 ki; lane 6) or TR1 and GPx1 knock-in genes (TR1 ki-GPx1 ki; lane 7) as shown in the figure. Cells that were stably transfected with the pU6 control construct were transiently transfected with pcDNA3.1 expression control vector also served as a control (lane 1). Transfected cells were labeled with 75Se, cell extracts prepared and the expressed selenoproteins visualized by PhosphorImager analysis of 75Se incorporation into proteins following separation by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis. Another set of control cells that gave virtually identical results as the corresponding stably transfected cells subsequently transfected with the pcDNA3 expression vector (see lanes 1 and 2) were stably transfected with the pU6 construct or with the double shTR1-shGPx1 construct (data not shown).

Table 2.

Troubleshooting table.

| Step | Problem | Possible reason | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | Cells grow extremely slow or all die during stabilization. | shRNA cell toxicity. If cells transfected with a control vector show the same phenotype as shRNA transfected cells, it could be due to U6 promoter toxicity. | Use the H1 promoter to replace the U6 promoter26, or use an inducible U6 promoter vector11 to control the expression level and reduce cell toxicity. |

| The shRNA targeted gene(s) are essential to cell growth. | Use an inducible U6 promoter vector11, or co-transfect the gene expression vector(s) for gene(s) replacement (see step 38B). | ||

| Low knockdown efficiency. | Target sequences are not efficient. | Reselect more shRNA target sequences to screen. | |

| Some knockdown phenotypes are only observed with one of the effective shRNAs. | Caused by off-targeting effects. | Use a BLAST search to screen shRNA target regions to avoid identity to other genes, especially the seed region38,39. | |

| Select at least two of the effective shRNAs with the same effects. | |||

| 38 | Cells grow extremely slowly or all die during stabilization. | If all of the single shRNA transfected cells generated in step 24 did not show significant cell growth problem, but the multiple shRNA vector transfected does, it is possibly caused by the loss of function of multiple genes. | Use an inducible U6 promoter vector11. |

| Cell toxicities might be caused by multiple shRNA expression. | Use another promoter such as H1. | ||

| Use an inducible U6 promoter vector11 to control the expression level and reduce cell toxicity. | |||

| Some knockdown phenotypes are only observed in one combination of effective shRNAs, | Caused by off-targeting effects. | Always use two or more combinations of shRNAs when knocking down multiple genes. |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, NCI, Center for Cancer Research to DLH and NIH grants to VNG.

Footnotes

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hannon GJ. RNA interference. Nature. 2002;418:244–251. doi: 10.1038/418244a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Novina CD, Sharp PA. The RNAi revolution. Nature. 2004;430:161–164. doi: 10.1038/430161a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu XM, et al. Evidence for direct roles of two additional factors, SECp43 and soluble liver antigen, in the selenoprotein synthesis machinery. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:41568–41575. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506696200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jazag A, et al. Single small-interfering RNA expression vector for silencing multiple transforming growth factor-beta pathway components. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e131. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ter BO, Konstantinova P, Ceylan M, Berkhout B. Silencing of HIV-1 with RNA interference: a multiple shRNA approach. Mol. Ther. 2006;14:883–892. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang S, Shi Z, Liu W, Jules J, Feng X. Development and validation of vectors containing multiple siRNA expression cassettes for maximizing the efficiency of gene silencing. BMC. Biotechnol. 2006;6:50. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-6-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gou D, et al. A novel approach for the construction of multiple shRNA expression vectors. J. Gene Med. 2007;9:751–763. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dafny-Yelin M, Chung SM, Frankman EL, Tzfira T. pSAT RNA interference vectors: a modular series for multiple gene down-regulation in plants. Plant Physiol. 2007;145:1272–1281. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.106062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song J, Giang A, Lu Y, Pang S, Chiu R. Multiple shRNA expressing vector enhances efficiency of gene silencing. BMB. Rep. 2008;41:358–362. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2008.41.5.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yan Y, Zhang J, Guo JL, Huang W, Yang YZ. Multiple shRNA-mediated knockdown of TACE reduces the malignancy of HeLa cells. Cell Biol. Int. 2009;33:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu XM, et al. Selenophosphate synthetase 2 is essential for selenoprotein biosynthesis. Biochem. J. 2007;404:115–120. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang Y, Price DH. Rescue of the TTF2 knockdown phenotype with an siRNA-resistant replacement vector. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:1151–1153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim DH, Rossi JJ. Coupling of RNAi-mediated target downregulation with gene replacement. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 2003;13:151–155. doi: 10.1089/108729003768247619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O′Reilly M, et al. RNA interference-mediated suppression and replacement of human rhodopsin in vivo. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:127–135. doi: 10.1086/519025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jallow Z, Jacobi UG, Weeks DL, Dawid IB, Veenstra GJ. Specialized and redundant roles of TBP and a vertebrate-specific TBP paralog in embryonic gene regulation in Xenopus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:13525–13530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405536101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Unwalla HJ, et al. Novel Pol II fusion promoter directs human immunodeficiency virus type 1-inducible coexpression of a short hairpin RNA and protein. J. Virol. 2006;80:1863–1873. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.4.1863-1873.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laatsch A, Ragozin S, Grewal T, Beisiegel U, Joerg H. Differential RNA interference: replacement of endogenous with recombinant low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP) Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2004;83:113–120. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoo MH, et al. A new strategy for assessing selenoprotein function: siRNA knockdown/knock-in targeting the 3′-UTR. RNA. 2007;13:921–929. doi: 10.1261/rna.533007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Low SC, Berry MJ. Knowing when not to stop: selenocysteine incorporation in eukaryotes. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1996;21:203–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimchi-Sarfaty C, et al. A “silent” polymorphism in the MDR1 gene changes substrate specificity. Science. 2007;315:525–528. doi: 10.1126/science.1135308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsieh AC, et al. A library of siRNA duplexes targeting the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway: determinants of gene silencing for use in cell-based screens. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:893–901. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krueger U, et al. Insights into effective RNAi gained from large-scale siRNA validation screening. Oligonucleotides. 2007;17:237–250. doi: 10.1089/oli.2006.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kiang A, et al. Fully deleted adenovirus persistently expressing GAA accomplishes long-term skeletal muscle glycogen correction in tolerant and nontolerant GSD-II mice. Mol. Ther. 2006;13:127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sano M, Kato Y, Akashi H, Miyagishi M, Taira K. Novel methods for expressing RNA interference in human cells. Methods Enzymol. 2005;392:97–112. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)92006-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scherer LJ, Frank R, Rossi JJ. Optimization and characterization of tRNA-shRNA expression constructs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:2620–2628. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.An DS, et al. Optimization and functional effects of stable short hairpin RNA expression in primary human lymphocytes via lentiviral vectors. Mol. Ther. 2006;14:494–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Makinen PI, et al. Stable RNA interference: comparison of U6 and H1 promoters in endothelial cells and in mouse brain. J. Gene Med. 2006;8:433–441. doi: 10.1002/jgm.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bannister SC, Wise TG, Cahill DM, Doran TJ. Comparison of chicken 7SK and U6 RNA polymerase III promoters for short hairpin RNA expression. BMC. Biotechnol. 2007;7:79. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-7-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lambeth LS, Wise TG, Moore RJ, Muralitharan MS, Doran TJ. Comparison of bovine RNA polymerase III promoters for short hairpin RNA expression. Anim Genet. 2006;37:369–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2006.01468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koper-Emde D, Herrmann L, Sandrock B, Benecke BJ. RNA interference by small hairpin RNAs synthesised under control of the human 7S K RNA promoter. Biol. Chem. 2004;385:791–794. doi: 10.1515/BC.2004.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawasaki H, Taira K. Short hairpin type of dsRNAs that are controlled by tRNA(Val) promoter significantly induce RNAi-mediated gene silencing in the cytoplasm of human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:700–707. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paul CP, et al. Localized expression of small RNA inhibitors in human cells. Mol. Ther. 2003;7:237–247. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(02)00038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grimm D, et al. Fatality in mice due to oversaturation of cellular microRNA/short hairpin RNA pathways. Nature. 2006;441:537–541. doi: 10.1038/nature04791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.ter BO, et al. Lentiviral vector design for multiple shRNA expression and durable HIV-1 inhibition. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:557–564. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elbashir SM, Martinez J, Patkaniowska A, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. Functional anatomy of siRNAs for mediating efficient RNAi in Drosophila melanogaster embryo lysate. EMBO J. 2001;20:6877–6888. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.23.6877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reynolds A, et al. Rational siRNA design for RNA interference. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004;22:326–330. doi: 10.1038/nbt936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoo MH, Xu XM, Carlson BA, Gladyshev VN, Hatfield DL. Thioredoxin reductase 1 deficiency reverses tumor phenotype and tumorigenicity of lung carcinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:13005–13008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600012200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Birmingham A, et al. 3′ UTR seed matches, but not overall identity, are associated with RNAi off-targets. Nat. Methods. 2006;3:199–204. doi: 10.1038/nmeth854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin X, et al. siRNA-mediated off-target gene silencing triggered by a 7 nt complementation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:4527–4535. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Svoboda P. Off-targeting and other non-specific effects of RNAi experiments in mammalian cells. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 2007;9:248–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Novoselov SV, et al. Selenoprotein H is a nucleolar thioredoxin-like protein with a unique expression pattern. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:11960–11968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701605200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoo MH, et al. Targeting thioredoxin reductase 1 reduction in cancer cells inhibits self-sufficient growth and DNA replication. PLoS. ONE. 2007;2:e1112. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sambrook J, Russell DW. Extraction, Purification, and Analysis of mRNA from Eukaryotic Cells. In: Sambrook J, Russell DW, editors. Molecular Cloning--A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor; New York: 2001. pp. 1–94. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ding F, Grabowski PJ. Identification of a protein component of a mammalian tRNA(Sec) complex implicated in the decoding of UGA as selenocysteine. RNA. 1999;5:1561–1569. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299991598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carlson BA, et al. Identification and characterization of phosphoseryl-tRNA[Ser]Sec kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:12848–12853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402636101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu XM, et al. Biosynthesis of Selenocysteine on Its tRNA in Eukaryotes. PLoS. Biol. 2007;5:96–105. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]