Abstract

Lupus is an antibody-mediated autoimmune disease. The production of pathogenic, class switched and affinity maturated autoantibodies in lupus is dependent on T cell help. A potential mechanism of disease pathogenesis is a lack of control of pathogenic T helper cells by regulatory T cells in lupus. It has been repeatedly shown that the naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in lupus prone mice and patients with SLE are defective both in frequency and function. Thus, the generation of inducible regulatory T cells that can control T cell help for autoantibody production is a potential avenue for the treatment of SLE. We have found that oral administration of anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody attenuated lupus development and arrested on-going disease in lupus prone SNF1 mice. Oral anti-CD3 induces a CD4+CD25-LAP+ regulatory T cell that secrets high levels of TGF-β and suppresses in vitro in TFG-β-dependent fashion. Animals treated with oral anti-CD3 had less glomerulonephritis and diminished levels of anti-dsDNA autoantibodies. Oral anti-CD3 led to a downregulation of IL-17+CD4+ICOS-CXCR5+ follicular helper T cells, CD138+ plasma cells and CD73+ mature memory B cells. Our results show that oral anti-CD3 induces CD4+CD25-LAP+ regulatory T cells that suppress lupus in mice and is associated with down regulation of T cell help for autoantibody production.

Keywords: CD4+CD25-LAP+ regulatory T cells, IL-17+ follicular helper T cells, oral anti-CD3, spontaneous lupus

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease characterised by an aberrant autoantibody and T-cell response against intracellularly derived self-antigens.1,2 T cell help is required for the production of high affinity IgG autoantibodies which are closely linked to tissue damage in lupus.3-6 A distinct subset of T cells, follicular helper T cells, selects mutated, high affinity B cells within germinal centers.7 Follicular helper T cells are emerging as a cellular subset with a functional programme different from that of extrafollicular Th1 or Th2 T cells: they express high levels of ICOS8,9 and have distinct patterns of gene expression of cytokines (predominantly IL-21) and chemokine receptor CXCR5.10,11 The expression of CXCR5 by these T cells allows them to localise to B cell follicles where they provide help to B cells. Mice lacking CXCR5 display major aberrations in splenic follicular architecture and reduced numbers of lymph nodes and Peyer’s patches.12,13

One of the hypotheses for the pathogenesis of SLE is that the number and function of naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells are defective.14-16 This is also true in lupus prone mice.17,18 It is possible that aberrant T cell help for autoantibody production by B cells is a result of defects in CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells.19-21 Thus, clinically applicable strategies to generate inducible regulatory T cells could be an effective strategy for treating SLE. We have identified and characterised a TGF-β-dependent regulatory T cell expressing latency-associated peptide (LAP) on the surface22,23 and have found that anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody given orally induces a CD4+CD25-LAP+ regulatory T cell that suppresses experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE)23 and diabetes 24 in mice by a TGF-β-dependent mechanism. LAP identifies a class of regulatory T cells that function in a TGF-β-dependent fashion.22,25-28 LAP is the aminoterminal domain of the TGF-β precursor peptide and remains non-covalently associated with the TGF-β peptide after cleavage, forming the latent TGF-β complex. CD4+LAP+ T cells appear to be distinct from naturally occurring CD25+ regulatory T cells, though it has been reported that CD4+CD25+ T cells may express TGF-β on their surface and mediate their suppressive function by presenting TGF-β to a receptor on target cells via cell-to-cell contact.22,26,28,29

We have previously shown suppression of lupus in mice following induction of nasal tolerance with a peptide (H471) expressing a dominant pathogenic T cell epitope in histone protein H4 of nucleosome.30 Given that only a subset of patients with SLE are sensitised to the H471 epitope, we tested the effect of oral anti-CD3 antibody on disease in both an accelerated31 and a spontaneous model of lupus. We hypothesised that oral administration of anti-CD3 antibody would induce regulatory T cells whose efficacy would not be restricted to a particular model and would thus be applicable for the treatment of human lupus. Anti-CD3 monoclonal antibodies given intravenously have been used to treat both animal models of autoimmunity32-36 and transplantation.37-39 Intravenously administered anti-CD4 has been tested for the treatment of murine lupus.40-42 Other studies have used a strategy to expand the naturally occurring CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells in vivo for the treatment of lupus using the histone peptide H47143 and a peptide based on anti-DNA Ig sequences.44,45 We demonstrate here that an inducible regulatory T cell generated by oral administration of anti-CD3 can control the function of follicular helper T cells leading to downregulation of B cell activity, autoantibody production and disease in lupus prone mice.

Methods and materials

Mice

(NZB × SWR)F1 (SNF1) mice were bred and maintained at our facility at the Harvard Institutes of Medicine. Parental female NZB and male SWR mice and lupus prone female (NZB × NZW)F1 (BWF1) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine, USA). Only female mice were used in our experiments. All mice were housed in specific pathogen-free environment according to the animal protocol guidelines of the Committee on Animals of Harvard Medical School, which also approved the experiments.

Antigens and antibodies

The histone peptide H471 based on the amino acid sequence of histone protein H4 at positions 71-93 was synthesised by F-moc chemistry (Biopolymer lab, Harvard Medical School). The peptide was purified by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using a gradient of water and acetonitrile and was analysed by mass spectrometry for purity (97%). Antibodies specific to CD3 (145-2c11) and CD28 (37.51) were used to stimulate T cells in vitro. In some experiments, neutralizing TGF-β (1D11) or relevant isotype control antibody (Bio Express, West Lebanon, New Hampshire, USA) was added to cell culture. Fluorescent (FITC or PE)-conjugated anti-mouse antibodies used in flow cytometry were CD4-specific (H129.19), CD25-specific (PC61), CXCR5-specific (2G8), ICOS-specific (7E17G9), IL-17-specific (TC11), CD138-specific (281-2), CD73-specific (TY/23), 7AAD and streptavidin-allophycocyamin (Sav-APC) (all from BD Biosciences, California, USA). For Fcγ receptor blocking, we used CD16/CD32-specific antibody. Affinity purified biotinylated goat LAP-specific polyclonal antibody was purchased from R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA. Anti-mouse foxp3 antibody was purchased from Ebioscience, San Diego, California, USA. All other monoclonal antibodies and respective isotype control antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Jose, California, USA.

Oral administration of antibody and immunization

Mice were orally dosed for five consecutive days with hamster IgG mouse CD3-specific F(ab’)2-specific antibody (clone 145-2C11, BioExpress) or hamster IgG control F(ab’)2 antibody (Jackson Immuno-Research Laboratories, West Grove, Pennsylvania, USA) dissolved in PBS (Phosphate Buffer Solution) or PBS alone. In disease studies, we orally treated mice with multiple courses (five consecutive doses as one course) of antibody at one-week intervals. To accelerate lupus development in SNF1 mice, each mouse received an intradermal injection of H471 peptide (100 μg) emulsified in CFA (Complete Freund’s Adjuvant) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) and an intraperitoneal injection of H471 (100 μg) in IFA (Incomplete Freund’s Adjuvant) 10 days later.

T-cell proliferation

Mesentric (MLNs) or peripheral (axial, brachial and inguinal, PLNs) lymph node cells or splenocytes were cultured in triplicate at 1.5 × 106/mL in the presence of various amounts of antigen or antibodies or alone in 96-well round bottom microtitre plates (Corning, Maine, New York, USA) for 96 h at 37 °c with 5% CO2 in a humid incubator. CD4+ T cells were negatively selected using a cocktail of antibodies against other cell types (R&D Systems). The purity of selected cells was checked by flow cytometry (Figure 2B). In all experiments, selection efficiency was over 95%. For cell sorting, CD4+ T cells or whole lymphocytes were incubated with biotinylated goat LAP-specific polyclonal antibody at 1 μg/million cells before being stained with fluorescent anti-mouse CD4, CD25 and Sav-APC (all at 0.5 μg/million cells). CD4+CD25-LAP- or CD4+CD25-LAP+ T cells were sorted using a FACSVantage SE (BD Biosciences). The purity of each population was over 95% by flow cytometry analysis (Figure 2C). Tissue culture medium was RPMI-1640 with 4.5 g/L glucose and L-Glutamine (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, Maryland, USA) supplemented with 2% penicillin and streptomycin (BioWhittaker) and 1% foetal calf serum. Cultures were pulsed with 0.25 μci tritiated thymidine ([3H]d Thd; PerkinElmer, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) for the last 6 h. [3H]d Thd incorporation was measured using a liquid scintillation beta counter (Wallac, PerkinElmer). Cell proliferation was expressed in delta CPM(Δ CPM).

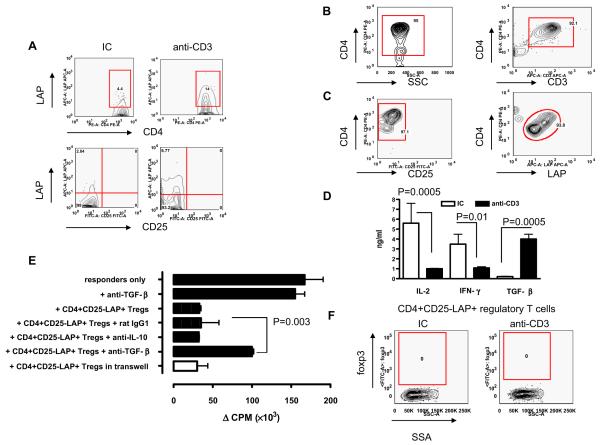

Figure 2.

In-vitro suppression by CD4+CD25-LAP+ regulatory T cells. (A) SNF1 mice (eight/group) were fed three 5-day courses of 5 μg isotype control (IC) or anti-CD3 antibody, and 90 days after the last feeding, splenocytes were examined by flow cytometry. Analysis was performed on gated CD4+CD25-7AAD- auto-fluorescent negative T cells. Representative contour plots of two independent experiments are shown. Prior to functional tests, we analysed the purity of (B) negatively selected CD4+ T cells (CD3 expression shown is on gated CD4+ T cells) and (C) sorted CD4+CD25-LAP+ T cells (LAP expression shown is on gated CD4 +CD25-T cells). (D) SNF1 mice (four/group) were fed a 5-day course of 5 μg IC or anti-CD3 antibody, and 72 h after the last feeding, CD4+CD25-LAP+ T cells of IC (clear bars) or anti-CD3 (filled bars)-fed SNF1 mice were isolated from MLNs and cultured with plate bound anti-CD3, and anti-CD28 antibody and cytokines in culture supernatant were determined. This experiment was repeated four times with similar results (P values derived from t-tests). (E) SNF1 mice (eight/group) were fed a 5-day course of 5 μg IC or anti-CD3 antibody, and at 72 h after the last feeding, CD4+CD25-LAP+ T cells were sorted from MLNs and co-cultured with CD4+CD25-LAP-T cells sorted from PLNs of naive mice at a 1:1 ratio in the presence of soluble anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies plus anti-mouse TGF-β or IL-10 neutralizing antibodies or control antibody for 96 h (P value derived from two-way ANOVA test). Regulatory T cells (bottom chamber) and T-responder cells (top chamber) were also cultured in a transwell system with soluble anti-CD3 and anti-CD28. Proliferation represents responder T cells (P value derived from two-way ANOVA test). This experiment was repeated four times and a representative experiment is shown. (F) CD4+CD25-LAP+ T cells were sorted from MLNs following a course of feeding, fixed and permeablised before being stained with biotinlyted anti-mouse foxp3 antibody and FITC-conjugated streptavidin.

Histology and immunofluorescent staining

Mouse kidneys were fixed in 10% formalin (Fisher, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA). Before periodic acid schiff’s (PAS) staining, kidneys were embedded in paraffin (Tissue-Tek, Torrance, California, USA), and 5 μM kidney sections were cut on a cryostat. For immunofluorescent staining, frozen kidney sections were air dried from -80 °C for 30 min, fixed in 100% alcohol for 1 min and bleached with 0.1% sodium borohydride (Sigma) in PBS for 10 min at room temperature (RT). Sections were then washed twice with PBS and non-specific binding sites were blocked with 10% normal rat serum in PBS for 1 h at RT. Following two further washes with PBS, kidney sections were stained with FITC- or PE-conjugated antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon, USA) for 1 h at RT in dark. Unbound antibodies were washed away with PBS and sections were embedded in Vectashield (Vector Labs, Burlingame, California, USA). Slides were examined using an Axioskop 2 plus fluorescence illumination system (Zeiss, Thornwood, New York, USA) in a blind-folded fashion.

Cytokine detection

The level of cytokines produced in vitro by cell cultures was determined using BD OptEIA ELISA set and reagent set B (BD Biosciences). Samples were tested in triplicate using the manufacturer’s recommended assay procedure. Cell culture supernatant was harvested at different time points (24 h for IL-2; 72 h for IFN-γ; 90 h for TGF-β) for the detection of cytokines.

Flow cytometry

Cells were washed (12000 RPM, 5 min at 4 °C) with PBS containing 2% bovine serum albumin (PBS/BSA, BioWhittaker). Fcγ receptors were blocked by incubation with anti-CD16/CD32 antibody for 30 min at 4 °C. Cells were washed twice before being stained with FITC-, PE- or APC-conjugated anti-mouse cell surface molecule antibodies (1 μg/106cells/test) or relevant IC antibody for 30 min at 4 °C in dark. After staining, cells were washed again with PBS/BSA before flow cytometry (FACScan™, Becton Dickson, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA). For intracellular foxp3 and IL-17 staining, cells (10 × 107 cells/mL) in culture medium containing 1 μL GolgiSTOP (BD Biosciences) were stimulated with PMA (Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate) (50 ng/mL) and ionomycin (1000 ng/mL) for 4 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in humid incubator. After incubation, cells were fixed and permeabilised before being stained. All FACs data were analysed using FlowJo software (TreeStar).

ELISA for serum autoantibodies

Autoantibodies were measured as described previously.30 Briefly, double stranded DNA (dsDNA) was used at 20 μg/mL. For the detection of total IgG or IgG1 or IgG2a antibodies, 50 μL/well of HRP-conjugated rat anti-mouse antibody (BD Bioscieces) at 1:1000 dilution was added and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h.

Statistical analysis

Statistical differences in cell proliferation and circulating IgG levels were derived from two-way ANOVA and Student’s t-test, respectively. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used for all the pair wise group comparisons. A closed testing procedure was used to control for multiple comparisons, and the appropriately adjusted P values were reported. A P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

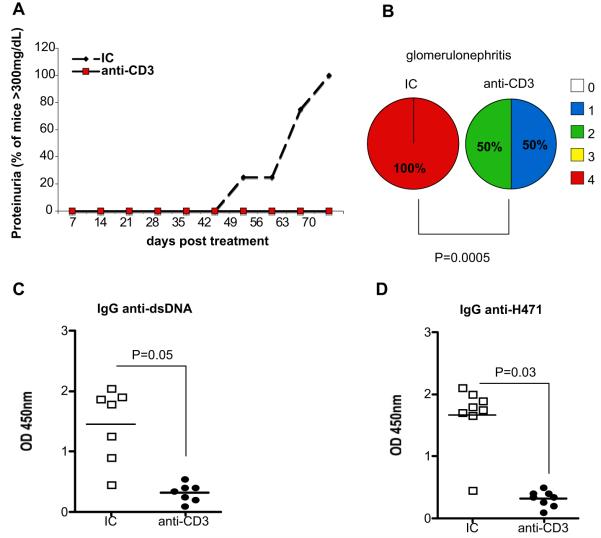

Oral anti-CD3 suppresses lupus development in H471 peptide-accelerated SNF1 model

Systemic immunization of SNF1 mice with peptide H471 expressing a dominant pathogenic T-cell epitope in histone protein H4 rapidly accelerates the development of lupus in these mice by promoting a cognate interaction between nucleosome reactive T and B cells.30,31 Young (4-6 weeks) female SNF1 mice received orally three 5-day courses of 5 μg oral isotype control (IC) or anti-CD3 antibody every other week over a 6-week period before immunization with H471 peptide. As shown in Figure 1A, oral anti-CD3-treated mice did not develop severe proteinuria (>300 mg/dL) compared with IC-treated controls. Quantification of glomerulonephritis by PAS staining of kidney sections showed no incidence of severe glomerulonephritis (>grade 3) in oral anti-CD3-treated mice, whereas 100% of control mice developed end stage glomerulonephritis (P = 0.0005, Figure 1B). Furthermore, oral anti-CD3 suppressed the production of IgG autoantibodies to dsDNA and histone peptide H471 (Figure 1C and 1D, respectively). Thus, oral anti-CD3 given before the onset of lupus resulted in attenuation of disease severity and progression.

Figure 1.

Suppression of accelerated lupus by oral anti-CD3. (A) SNF1 mice (eight/group) were fed three 5-day courses of 5 μg isotype control (IC) or anti-CD3 antibody before immunization with H471 peptide to accelerate lupus development. Proteinuria was measured weekly. This experiment was repeated once with similar results. (B) On day 90 following H471 peptide immunization, kidney pathology was examined by PAS. Kidneys of all mice-fed IC (left) or anti-CD3 (right) antibody were graded by light microscopy on a scale of 0-4 as follows: 0 - no lesions; 1 - minor thickening of capillaries; 2 - focal and/or diffuse thickening of capillaries in 30-60% of the glomeruli; 3 - all capillaries of all glomeruli affected and 4 - sclerosis of glomeruli and numerous tubular casts. Percentages of glomerulonephritis scores in each group are presented as pie charts (P value derived from Wilcoxon rank sum test). (C) anti-dsDNA and (D) anti-H471 autoantibodies in mouse serum were measured by ELISA with 1 in 1000 dilution of serum (P value derived from t-test). Each symbol represents one mouse and means of each group are represented by cross bars.

Oral anti-CD3 induced CD4+CD25-LAP+ regulatory T cells that suppress effector T-cell proliferation in vitro in a TGF-β-dependent fashion

We have shown that oral anti-CD3 induced a CD4+CD25-LAP+ regulatory T cell that suppressed EAE23 and diabetes24 in a TGF-β-dependent fashion. Thus, we tested for CD4+CD25-LAP+ T cells in spleens of mice orally treated with anti-CD3. Young female SNF1 mice were orally treated with three 5-day courses of 5 μg oral IC or anti-CD3 antibody every other week over a 6-week period before immunization with H471 peptide to accelerate disease. Figure 2B shows that CD4+CD25-LAP+ T cells were markedly upregulated in spleens of mice treated with oral anti-CD3 but not IC 90 days after treatment. Prior to functional tests, we analysed the purity of negatively selected CD4+ T cells (Figure 2B) and CD4+CD25-LAP+ T cells post sorting (Figure 2C) and they were both over 95% pure. We found the CD4+CD25-LAP+ T cells of oral anti-CD3-treated mice secreted higher levels of TGF-β but lower levels of IL-2 and IFN-γ compared with IC-treated controls (Figure 2D). To test the suppressive function of CD4+CD25-LAP+ T cells and the role of TGF-β in the mechanism of suppression, CD4+CD25-LAP+ T cells were co-cultured with CD4+CD25-LAP-responder T cells in the presence of a neutralising anti-TGF-β antibody or an anti-IL-10 or an isotype control antibody. We also tested the necessity for physical contact between the regulatory and responder in suppression using a transwell system. Figure 2E shows that CD4+CD25-LAP+ regulatory T cells suppressed the proliferation of responder T cells and suppression was partially reversed (68%) when TGF-β was neutralised in vitro. Furthermore, suppression of responder proliferation by CD4+CD25-LAP+ regulatory T cells was not cell contact dependent as separation of the two populations in a transwell did not affect suppression (Figure 2E). CD4+CD25-LAP+ regulatory T cells induced by oral anti-CD3 do not express the regulatory T cell transcription factor foxp3.20,46 These findings are consistent with our previous observations in oral anti-CD3 studies in EAE animals.23

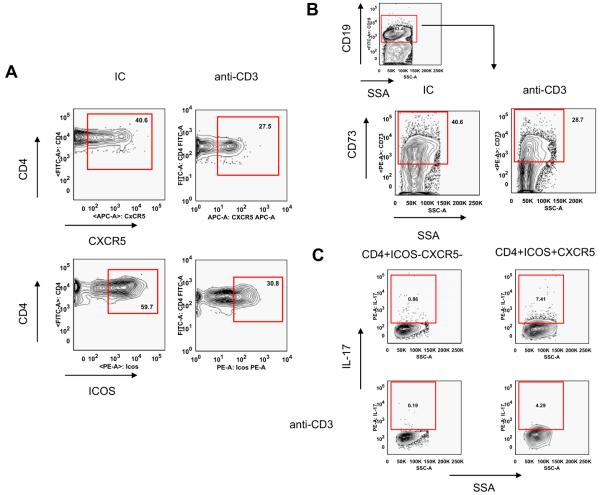

Oral anti-CD3 treatment downregulated the generation of IL-17+CD4+ICOS+CXCR5+ follicular helper T cells and memory B cells in SNF1 mice

We show above that suppression of lupus in SNF1 mice by oral anti-CD3 is associated with a significant reduction in anti-dsDNA autoantibody production. We hypothesised that suppression of autoantibody production following oral antiCD-3 was due to an effect of oral anti-CD3 on T-helper cells. To examine the effect of oral anti-CD3 on CD4+ICOS+CXCR5+ follicular helper T cells, we analysed the percentage of follicular helper T cells and memory B cells in spleens of SNF1 mice 90 days following oral anti-CD3 treatment. Figure 3A shows that 90 days following oral anti-CD3 treatment, the follicular helper T-cell population was reduced compared with controls (from 40.6% to 27.5%). This was accompanied by a reduction in CD19+CD73+ memory B cells (40.6%-28.7%, Figure 3B). We have found that CD4+ICOS +CXCR5+ follicular helper T cells express high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-17 compared with conventional CD4+ICOS-CXCR5- T cells.49 We found that oral anti-CD3 treatment in SNF1 mice downregulated the expression of IL-17 by CD4 +ICOS+CXCR5+ follicular helper T cells (from 7.41% to 4.29%, Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Oral anti-CD3 downregulated follicular helper T cells, memory B cells and IL-17 expression. SNF1 mice (eight/group) were fed three 5-day courses of 5 μg isotype control (IC) or anti-CD3 antibody, and 90 days after the last feeding, splenocytes were examined by flow cytometry. Analysis was performed on gated 7AAD- auto-fluorescent negative (A) CD4+ T cells and (B) CD19+ B cells. Representative contour plots of two independent experiments are shown here. (C) CD4+ICOS-CXCR5-conventional T cells and CD4+ICOS+CXCR5+ follicular helper T cells were sorted from spleens of IC or anti-CD3-fed mice on day 90 after the last feeding, fixed and permeablised before being stained with PE-conjugated anti-mouse IL-17 antibody.

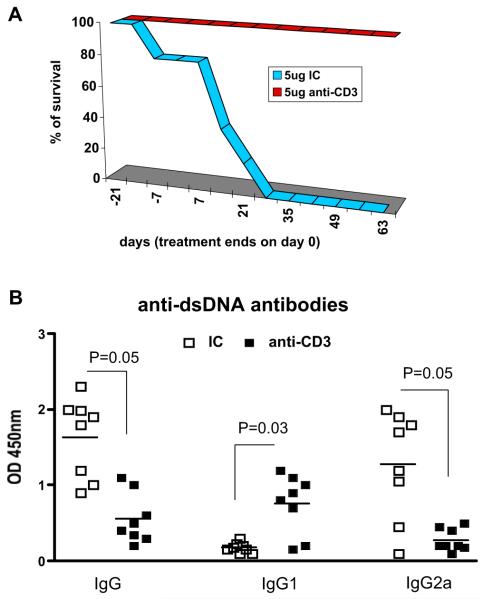

Oral anti-CD3 prolonged survival and downregulated plasma cells and memory B cells in the spleen and suppressed infiltration of IL-17+CD4+ inflammatory T cells in kidneys of SNF1 mice with spontaneous lupus

We then investigated the effect of oral anti-CD3 after disease onset in animals that had spontaneously developed lupus. We orally treated 6-month-old female SNF1 mice that had developed spontaneous lupus with six 5-day courses of 5 μg IC or anti-CD3 antibody every other week over a 12-week period and followed mice for survival. Figure 4A shows that all oral anti-CD3-treated animals survived beyond 90 days following treatment. Improved survival in mice orally administered anti-CD3 was associated with downregulation of IgG anti-dsDNA autoantibodies. In addition, we found a significant switch in anti-dsDNA autoantibodies from a Th1 subclass, IgG2a to a Th2 subclass and IgG1 (Figure 4B). Therefore, oral anti-CD3 improved on-going disease and suppressed pathogenic inflammatory anti-dsDNA autoantibodies that are hallmarks of SLE.

Figure 4.

Oral anti-CD3 improved survival and downregulated autoantibody production in SNF1 mice with spontaneous lupus. (A) SNF1 mice (eight/group) at 7-month old with persistent proteinuria (three consecutive weekly reading of >300 mg/dL) were fed six 5-day courses of 5 μg isotype control (IC) or anti-CD3 antibody over 12 weeks. Mice were followed for 90 days after treatment and percentage of survival in each treatment group was recorded weekly. This experiment was repeated once with similar results. (B) SNF1 mouse serum diluted 1 in 1000 was used in ELISA for the detection of IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a anti-dsDNA antibodies (P value derived from t-test). Each symbol represents one mouse and means of each group are represented by cross bars.

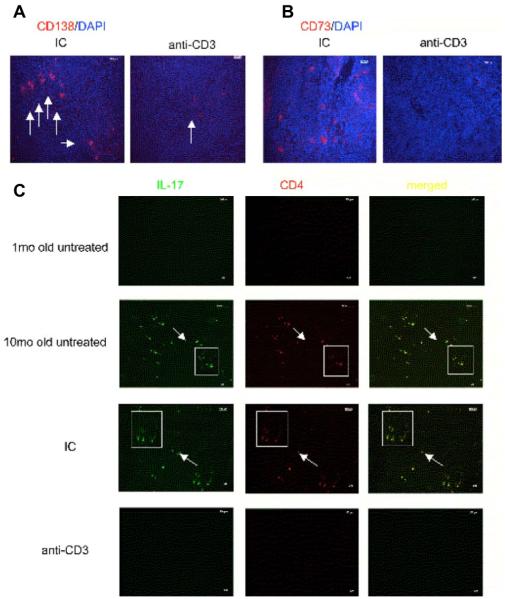

We then investigated whether oral anti-CD3 affected CD138+ plasma cells and CD73+ memory B cells in the spleen and infiltrating IL-17+CD4+ inflammatory T cells in kidneys.47 We found that following oral anti-CD3 treatment in the spontaneous SNF1 mouse model, there was a marked reduction in CD138+ plasma cells and CD73+ memory B cells in the spleen compared with control mice (Figure 5A and 5B, respectively). In addition, we stained for IL-17+CD4+ T cells in frozen kidney sections. Figure 5C shows that 10-month-old SNF1 mice with spontaneous lupus have large numbers of CD4+ T cells in the kidney and the majority of these CD4+ T cells are IL-17+ inflammatory T cells (second row), whereas these cells are absent in 1-month-old pre-nephritic mice (top row). Following treatment with oral anti-CD3, there was almost no T-cell infiltration in kidneys (bottom row), whereas IC-treated mice had T-cell infiltration (third row) that was comparable to 10-month-old untreated mice with spontaneous disease. Thus, oral anti-CD3 suppression of spontaneous lupus in SNF1 mice was associated with downregulating humoral responses and inflammatory T-cell infiltration in the kidney.

Figure 5.

Oral anti-CD3 downregulated plasma cell and memory B-cell formation in spleens and reduced IL-17+ inflammatory T-cell deposition in kidneys of SNF1 mice with spontaneous lupus. SNF1 mice (eight/group) at 7-month old with persistent proteinuria (three consecutive weekly reading of >300 mg/dL) were fed six 5-day courses of 5 μg isotype control (IC) or anti-CD3 antibody over 12 weeks. In all, 90 days after the last feeding, spleens were harvested and stained with (A) Alexa fluor 594 anti-mouse CD138 or (B) CD73 antibody. Pictures were taken at ×40 magnification. (C) Mouse kidney sections were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IL-17 and PE-conjugated anti-mouse CD4 antibodies. Pictures were taken at ×10 magnification.

Discussion

Accumulating evidence from both animal and human studies point to an important role of regulatory T cells in the aetiology and pathogenesis of SLE.48 We have previously shown that nasal tolerance to histone peptide H471 suppresses lupus via T-cell anergy30 and that nasal anti-CD3 suppresses lupus via IL-10.49 In this study, we show oral anti-CD3 induced CD4+CD25-LAP+ regulatory T cells that suppressed effector T-cell function in a TGF-β-dependent, cell-contact independent fashion. Oral anti-CD3 in mice prone to developing lupus significantly reduced disease pathology and extended survival of mice beyond their life expectancy. Furthermore, suppression of disease was associated with down regulation of inflammatory IL-17+CD4+ICOS+CXCR5+ follicular helper T cells, plasma cells and memory B cells. We have previously shown that oral anti-CD3 suppresses murine models of EAE23 and diabetes.24 We now demonstrate that oral anti-CD3 can suppress lupus, a prototypic antibody-mediated disease in mice. We studied the therapeutic effects of oral anti-CD3 in a peptide-accelerated lupus model in SNF1 mice. Lupus prone SNF1 mice uniformly produce pathogenic anti-DNA autoantibodies under the influence of certain Th cells and develop severe lupus glomerulonephritis.50-52 Th clones derived from nephritic SNF1 mice rapidly induce immune deposit glomerulonephritis when transferred in vivo into young preautoimmune SNF1 mice.53 Approximately 50% of such pathogenic T-cell clones are highly responsive to nucleosomal antigens54 and one of the determinants is in histone protein H4 sequence 71-94.31 Systemic immunisation of histone peptide H471 in SNF1 mice leads to early development of autoantibodies and glomerulonephritis.30 Oral anti-CD3 prior to systemic immunisation of H471 in SNF1 mice suppressed the development of severe glomerulonephritis and proteinuria. This was associated with a downregulation of IgG anti-dsDNA and anti-H471 autoantibodies.

We previously showed oral anti-CD3 led to the induction of CD4+CD25-LAP+ regulatory T cells.23,24 The anti-CD3 antibody was rapidly taken up in the intestinal tract and appeared in the villous epithelium within 30 min and increased at 1 h and 3 h after feeding.23 After oral anti-CD3, LAP+ regulatory T cells are first induced in the mesenteric lymph nodes after which they migrate to sites of inflammation. Thus, we observed increased numbers of LAP+ T cells in the popliteal lymph nodes in EAE animals immunised with proteolipid protein in CFA.23 In addition, in our oral anti-CD3 study in animals with streptozocin-induced diabetes, we found an increase of LAP+ T cells in the pancreatic lymph nodes.24 Thus, it appears that one of the properties of LAP+ regulatory T cells is their ability to migrate to sites of inflammation where they exert their regulatory effects. Furthermore, we eluted anti-CD3 antibody from the upper intestine of anti-CD3-fed animals and found that the eluted anti-CD3 antibody was biologically active in that it was able to stimulate naive T-cell proliferation to an equivalent of ∼0.01 μg/mL of anti-CD3 antibody in vitro.24 The CD4+CD25-LAP+ regulatory T cell express surface LAP which identifies a class of regulatory T cells that function in a TGF-β-dependent fashion.22,25-28 LAP is the aminoterminal domain of the TGF-β precursor peptide and remains non-covalently associated with the TGF-β peptide after cleavage, forming the latent TGF-β complex. We studied purified (above 95% purity) CD4+CD25-LAP+ T cells from oral anti-CD3-treated SNF1 mice by real time RTPCR (Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction) and found the relative expression of TGF-β was five times higher than CD4+CD25-LAP-T cell (data not shown). This finding was also demonstrated in our previous study on oral anti-CD3 in EAE mice.23 CD4+LAP+ T cells appear to be distinct from naturally occurring CD25+ regulatory T cells, though it has been reported that CD4+CD25+ T cells may express TGF-β on their surface and mediate their suppressive function by presenting TGF-β to a receptor on target cells via cell-to-cell contact.22,26,28,29 In this study, we also find that oral anti-CD3 in lupus prone SNF1 mice led to the upregulation of CD4+CD25-LAP+ regulatory T cells that were still detectable 90 days after treatment. This suggests that, like the naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells, the inducible CD4+CD25-LAP+ regulatory T cells are able to persist in the periphery. We did not observe changes in frequency of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells following oral anti-CD3. In addition, the inducible LAP+ regulatory T cells suppress effector T-cell function in a TGF-β-dependent fashion. However, in contrast to the former, the latter do not express the molecular marker foxp3, and suppression does not require direct contact between the regulator and responder. These findings suggest that there are fundamental differences between naturally occurring and inducible regulatory T cells. Generation of inducible regulatory T cells can be beneficiary to SLE in that they can restore the deficit in immune regulation due to a lack of naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells.16,17

The production of nephritogenic antinuclear autoantibodies in SLE is driven by cognate interactions between select populations of autoimmune Th and B cells.51,55-57 A distinct subset of T cells, follicular helper T cells, selects mutated, high affinity B cells within germinal centers,7 and they are needed to initiate plasma cell generation58,59 and antibody production.60,61 Numerous recent studies have shown that IL-17 producing T-helper cells constitute a distinct CD4+ T-helper population that differs in function and phenotype from classical T-helper type-1 and type-2 populations.62 IL-17 is linked to the induction of autoreactive humoral immune response because a deficiency in or blockade of IL-17 is associated with a decline in the autoantibody response.63-65 Here, we find that follicular helper T cells in SNF1 mice express the inflammatory cytokine IL-17. This result correlates with findings by Hsu et al.66 which show autoimmune BXD2 mice express heightened levels of IL-17 and that IL-17 is required for the spontaneous development of germinal centres and production of pathogenic autoantibodies in these mice. Injection of antagonistic antibody to IL-17 in mice disrupted T and B cell interaction and the formation of germinal centres and autoantibodies.66 Oral anti-CD3 suppressed the formation of CD4+ICOS +CXCR5+ follicular helper T cells. This correlates with a downregulation of CD73+ memory B cells and autoantibodies following oral anti-CD3. Oral anti-CD3 also led to a downregulation of IL-17 expression by the follicular helper T cells. Oral anti-CD3 in mice with spontaneous lupus also resulted in reduced plasma cells in spleens and IL-17+CD4+ T-cell infiltration in kidneys. Thus, it appears that oral anti-CD3 suppresses lupus in mice by disrupting cognate interaction of follicular helper T cells and B cells thus reducing autoantibody production and antibody-antigen immune complex mediated glomerulonephritis.

We performed our experiments with a F(ab’)2 antibody to eliminate any potential side effects related to the Fc portion of the molecule that might occur after multiple administrations of the antibody orally. We observed no mitogenic effect of oral hamster CD3-specific F(ab’)2 antibody in mice and no evidence of cytokine release syndrome (wasted appearance, ruffled fur) even after 30 oral administrations. Further more, we did not observe an anti-globulin response against anti-CD3 in mice orally treated with anti-CD3 (data not shown). Oral administration of CD3-specific antibody is applicable for chronic therapy and would not be expected to have side effects including cytokine release syndromes and anti-globulin responses.

In summary, we have shown that oral anti-CD3 antibody induces a CD4+CD25-LAP+ regulatory T cell that suppressed T-helper cell function leading to downregulation of autoantibody production and glomerulonephritis in murine lupus and it is applicable for treatment of human SLE.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr Byron H Waksman for his critical assessment of our manuscript and Deneen Kozoriz for cell sorting.

References

- 1.Croker JA, Kimberly RP. SLE: challenges and candidates in human disease. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:580–586. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh RR. SLE: translating lessons from model systems to human disease. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:572–579. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ravirajan CT, Rahman MA, Papadaki L, et al. Genetic, structural and functional properties of an IgG DNA-binding monoclonal antibody from a lupus patient with nephritis. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:339–350. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199801)28:01<339::AID-IMMU339>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehrenstein MR, Katz DR, Griffiths MH, et al. Human IgG anti-DNA antibodies deposit in kidneys and induce proteinuria in SCID mice. Kidney Int. 1995;48:705–711. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okamura M, Kanayama Y, Amastu K, et al. Significance of enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for antibodies to double stranded and single stranded DNA in patients with lupus nephritis: correlation with severity of renal histology. Ann Rheum Dis. 1993;52:14–20. doi: 10.1136/ard.52.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahman A. Autoantibodies, lupus and the science of sabotage. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43:1326–1336. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker LS, Gulbranson-Judge A, Flynn S, Brocker T, Lane PJ. Co-stimulation and selection for T-cell help for germinal centres: the role of CD28 and OX40. Immunol Today. 2000;21:333–337. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01636-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hutloff A, Dittrich AM, Beier KC, et al. ICOS is an inducible T-cell co-stimulator structurally and functionally related to CD28. Nature. 1999;397:263–266. doi: 10.1038/16717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lohning M, Hutloff A, Kallinich T, et al. Expression of ICOS in vivo defines CD4+ effector T cells with high inflammatory potential and a strong bias for secretion of interleukin 10. J Exp Med. 2003;197:181–193. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moser B, Schaerli P, Loetscher P. CXCR5(+) T cells: follicular homing takes center stage in T-helper-cell responses. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:250–254. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02218-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chtanova T, Tangye SG, Newton R, et al. T follicular helper cells express a distinctive transcriptional profile, reflecting their role as non-Th1/Th2 effector cells that provide help for B cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:68–78. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forster R, Mattis AE, Kremmer E, Wolf E, Brem G, Lipp M. A putative chemokine receptor, BLR1, directs B cell migration to defined lymphoid organs and specific anatomic compartments of the spleen. Cell. 1996;87:1037–1047. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81798-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ansel KM, Ngo VN, Hyman PL, et al. A chemokine-driven positive feedback loop organizes lymphoid follicles. Nature. 2000;406:309–314. doi: 10.1038/35018581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crispin JC, Martinez A, Alcocer-Varela J. Quantification of regulatory T cells in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun. 2003;21:273–276. doi: 10.1016/s0896-8411(03)00121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu MF, Wang CR, Fung LL, Wu CR. Decreased CD4+CD25+ T cells in peripheral blood of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Scand J Immunol. 2004;59:198–202. doi: 10.1111/j.0300-9475.2004.01370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valencia X, Yarboro C, Illei G, Lipsky PE. Deficient CD4 +CD25high T regulatory cell function in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2007;178:2579–2588. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu HY, Staines NA. A deficiency of CD4+CD25+ T cells permits the development of spontaneous lupus-like disease in mice, and can be reversed by induction of mucosal tolerance to histone peptide autoantigen. Lupus. 2004;13:192–200. doi: 10.1191/0961203303lu1002oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bagavant H, Tung KS. Failure of CD25+ T cells from lupus-prone mice to suppress lupus glomerulonephritis and sialoadenitis. J Immunol. 2005;175:944–950. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.2.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shevach EM. CD4+ CD25+ suppressor T cells: more questions than answers. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:389–400. doi: 10.1038/nri821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakaguchi S. Naturally arising CD4+ regulatory t cells for immunologic self-tolerance and negative control of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:531–562. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shevach EM, DiPaolo RA, Andersson J, Zhao DM, Stephens GL, Thornton AM. The lifestyle of naturally occurring CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:60–73. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oida T, Zhang X, Goto M, et al. CD4+CD25- T cells that express latency-associated peptide on the surface suppress CD4+CD45RBhigh-induced colitis by a TGF-beta-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2003;170:2516–2522. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ochi H, Abraham M, Ishikawa H, et al. Oral CD3-specific antibody suppresses autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inducing CD4(+)CD25(-)LAP(+) T cells. Nat Med. 2006;12:627–635. doi: 10.1038/nm1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishikawa H, Ochi H, Chen ML, Frenkel D, Maron R, Weiner HL. Inhibition of autoimmune diabetes by oral administration of anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody. Diabetes. 2007;56:2103–2109. doi: 10.2337/db06-1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller A, Lider O, Roberts AB, Sporn MB, Weiner HL. Suppressor T cells generated by oral tolerization to myelin basic protein suppress both in vitro and in vivo immune responses by the release of transforming growth factor beta after antigen-specific triggering. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:421–425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakamura K, Kitani A, Strober W. Cell contact-dependent immunosuppression by CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells is mediated by cell surface-bound transforming growth factor beta. J Exp Med. 2001;194:629–644. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.5.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen W, Jin W, Hardegen N, et al. Conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25- naive T cells to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by TGF-beta induction of transcription factor Foxp3. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1875–1886. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakamura K, Kitani A, Fuss I, et al. TGF-beta 1 plays an important role in the mechanism of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell activity in both humans and mice. J Immunol. 2004;172:834–842. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gandhi R, Anderson DE, Weiner HL. Cutting edge: immature human dendritic cells express latency-associated peptide and inhibit T cell activation in a TGF-beta-dependent manner. J Immunol. 2007;178:4017–4021. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu HY, Ward FJ, Staines NA. Histone peptide-induced nasal tolerance: suppression of murine lupus. J Immunol. 2002;169:1126–1134. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.2.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaliyaperumal A, Mohan C, Wu W, Datta SK. Nucleosomal peptide epitopes for nephritis-inducing T helper cells of murine lupus. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2459–2469. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chatenoud L, Primo J, Bach JF. CD3 antibody-induced dominant self tolerance in overtly diabetic NOD mice. J Immunol. 1997;158:2947–2954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tran GT, Carter N, He XY, et al. Reversal of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis with non-mitogenic, non-depleting anti-CD3 mAb therapy with a preferential effect on T(h)1 cells that is augmented by IL-4. Int Immunol. 2001;13:1109–1120. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.9.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Belghith M, Bluestone JA, Barriot S, Megret J, Bach JF, Chatenoud L. TGF-beta-dependent mechanisms mediate restoration of self tolerance induced by antibodies to CD3 in overt autoimmune diabetes. Nat Med. 2003;9:1202–1208. doi: 10.1038/nm924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang X, Hupperts R, De Baets M. Monoclonal antibody therapy in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis. Immunol Res. 2003;28:61–78. doi: 10.1385/IR:28:1:61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kohm AP, Williams JS, Bickford AL, et al. Treatment with nonmitogenic anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody induces CD4+ T cell unresponsiveness and functional reversal of established experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2005;174:4525–4534. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chavin KD, Qin L, Lin J, Yagita H, Bromberg JS. Combined anti-CD2 and anti-CD3 receptor monoclonal antibodies induce donor-specific tolerance in a cardiac transplant model. J Immunol. 1993;151:7249–7259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thomas FT, Ricordi C, Contreras JL, et al. Reversal of naturally occuring diabetes in primates by unmodified islet xenografts without chronic immunosuppression. Transplantation. 1999;67:846–854. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199903270-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mottram PL, Murray-Segal LJ, Han W, Maguire J, Stein-Oakley AN. Remission and pancreas isograft survival in recent onset diabetic NOD mice after treatment with low-dose anti-CD3 monoclonal antibodies. Transpl Immunol. 2002;10:63–72. doi: 10.1016/s0966-3274(02)00050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gutstein NL, Seaman WE, Scott JH, Wofsy D. Induction of immune tolerance by administration of monoclonal antibody to L3T4. J Immunol. 1986;137:1127–1132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carteron NL, Wofsy D, Seaman WE. Induction of immune tolerance during administration of monoclonal antibody to L3T4 does not depend on depletion of L3T4+ cells. J Immunol. 1988;140:713–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wofsy D. Treatment of murine lupus with anti-CD4 monoclonal antibodies. Immunol Ser. 1993;59:221–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kang HK, Michaels MA, Berner BR, Datta SK. Very low-dose tolerance with nucleosomal peptides controls lupus and induces potent regulatory T cell subsets. J Immunol. 2005;174:3247–3255. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.La Cava A, Ebling FM, Hahn BH. Ig-reactive CD4+CD25+ T cells from tolerized (New Zealand Black x New Zealand White)F1 mice suppress in vitro production of antibodies to DNA. J Immunol. 2004;173:3542–3548. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hahn BH, Singh RP, La Cava A, Ebling FM. Tolerogenic treatment of lupus mice with consensus peptide induces Foxp3-expressing, apoptosis-resistant, TGFbeta-secreting CD8+ T cell suppressors. J Immunol. 2005;175:7728–7737. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;299:1057–1061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kang HK, Liu M, Datta SK. Low-dose peptide tolerance therapy of lupus generates plasmacytoid dendritic cells that cause expansion of autoantigen-specific regulatory T cells and contraction of inflammatory Th17 cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:7849–7858. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu HY, Weiner HL. Oral tolerance. Immunol Res. 2003;28:265–284. doi: 10.1385/IR:28:3:265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu HY, Quintana FJ, Weiner HL. Nasal anti-CD3 antibody ameliorates lupus by inducing an IL-10 secreting CD4+CD25-LAP+ regulatory T cells and is associated with downregulation of IL-17+CD4+ICOS+CXCR5+ follicular heper T cells. J Immunol. 2008;181(9):6038–6050. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gavalchin J, Nicklas JA, Eastcott JW, et al. Lupus prone (SWR x NZB)F1 mice produce potentially nephritogenic autoantibodies inherited from the normal SWR parent. J Immunol. 1985;134:885–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Datta SK, Patel H, Berry D. Induction of a cationic shift in IgG anti-DNA autoantibodies. Role of T helper cells with classical and novel phenotypes in three murine models of lupus nephritis. J Exp Med. 1987;165:1252–1268. doi: 10.1084/jem.165.5.1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eastcott JW, Schwartz RS, Datta SK. Genetic analysis of the inheritance of B cell hyperactivity in relation to the development of autoantibodies and glomerulonephritis in NZB x SWR crosses. J Immunol. 1983;131:2232–2239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Adams S, Leblanc P, Datta SK. Junctional region sequences of T-cell receptor beta-chain genes expressed by pathogenic anti-DNA autoantibody-inducing helper T cells from lupus mice: possible selection by cationic autoantigens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:11271–11275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mohan C, Adams S, Stanik V, Datta SK. Nucleosome: a major immunogen for pathogenic autoantibody-inducing T cells of lupus. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1367–1381. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.5.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ando DG, Sercarz EE, Hahn BH. Mechanisms of T and B cell collaboration in the in vitro production of anti-DNA antibodies in the NZB/NZW F1 murine SLE model. J Immunol. 1987;138:3185–3190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sainis K, Datta SK. CD4+ T cell lines with selective patterns of autoreactivity as well as CD4- CD8- T helper cell lines augment the production of idiotypes shared by pathogenic anti-DNA autoantibodies in the NZB x SWR model of lupus nephritis. J Immunol. 1988;140:2215–2224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Desai-Mehta A, Mao C, Rajagopalan S, Robinson T, Datta SK. Structure and specificity of T cell receptors expressed by potentially pathogenic anti-DNA autoantibody-inducing T cells in human lupus. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:531–541. doi: 10.1172/JCI117695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ozaki K, Spolski R, Ettinger R, et al. Regulation of B cell differentiation and plasma cell generation by IL-21, a novel inducer of Blimp-1 and Bcl-6. J Immunol. 2004;173:5361–5371. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ettinger R, Sims GP, Fairhurst AM, et al. IL-21 induces differentiation of human naive and memory B cells into antibody-secreting plasma cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:7867–7879. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.7867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ozaki K, Spolski R, Feng CG, et al. A critical role for IL-21 in regulating immunoglobulin production. Science. 2002;298:1630–1634. doi: 10.1126/science.1077002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pene J, Gauchat JF, Lecart S, et al. Cutting edge: IL-21 is a switch factor for the production of IgG1 and IgG3 by human B cells. J Immunol. 2004;172:5154–5157. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bettelli E, Korn T, Kuchroo VK. Th17: the third member of the effector T cell trilogy. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:652–657. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nakae S, Nambu A, Sudo K, Iwakura Y. Suppression of immune induction of collagen-induced arthritis in IL-17-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2003;171:6173–6177. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.6173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Komiyama Y, Nakae S, Matsuki T, et al. IL-17 plays an important role in the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2006;177:566–573. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sonderegger I, Rohn TA, Kurrer MO, et al. Neutralization of IL-17 by active vaccination inhibits IL-23-dependent autoimmune myocarditis. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:2849–2856. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hsu HC, Yang P, Wang J, et al. Interleukin 17-producing T helper cells and interleukin 17 orchestrate autoreactive germinal center development in autoimmune BXD2 mice. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:166–175. doi: 10.1038/ni1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]