Abstract

Fusobacteria are most often associated with the classic presentation of Lemierre’s syndrome consisting of a sore throat, internal jugular vein thrombophlebitis, and septic emboli to the lungs. We present an unusual form of necrobacillosis presenting as pyomyositis and fasciitis due to F. necrophorum. We provide a review of the literature including an update on the diagnosis and treatment of these unusual infections.

Keywords: Fusobacterium, Lemierre’s syndrome, pyomyositis

Fusobacterium necrophorum is an obligate anaerobic gram-negative bacterium most commonly associated with Lemierre’s syndrome characterized by septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein, high fevers, and metastatic septic emboli. Necrobacillosis is the English term describing the necrotic abscesses associated fusobacterium sepsis. Most cases of F. necrophorum occur in association with an antecedent pharyngitis or head/neck infection; in fact, the first published report in 1900 described a patient who died of sepsis after developing tonsillitis [1]. We describe an unusual case of necrobacillosis presenting as a lower extremity pyomyositis and fasciitis, sepsis, and pulmonary septic emboli in a young male without signs or symptoms of a preceding pharyngotonsillitis and provide a review of the literature.

Case Report

A 17-year-old Caucasian male presented with progressive fevers and right calf pain. He developed nausea, abdominal pain, and diarrhea one week prior to admission, after which he noted right calf pain and difficulty ambulating. He had no significant past medical history and was taking no medications. He was a student at a local high school and denied use of illicit drugs or alcohol. His review of systems was negative for a sore throat or neck pain.

On physical examination his blood pressure was 104/56 mmHg, and he had a pulse of 134 beats/minute, respiratory rate of 16, and a temperature of 100.8 °F. His examination was only significant for tenderness and edema involving the calf and popliteal fossa. Oropharyngeal, neck, skin, and lung evaluations were unremarkable. Laboratories revealed a white blood count of 42,900 cells/mm3, with 79% neutrophils and 16% bands. Platelets were depressed at 88,000/mm3. The chemistry panel was normal; liver function tests showed an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 64 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 28 IU/L, alkaline phosphotase of 239 IU/L, albumin of 3.4 g/dl, and creatine kinase of 141 IU/L. The chest radiograph showed a right perihilar infiltrate, and the patient was diagnosed presumptively with pneumonia and treated with ceftriaxone and azithromycin.

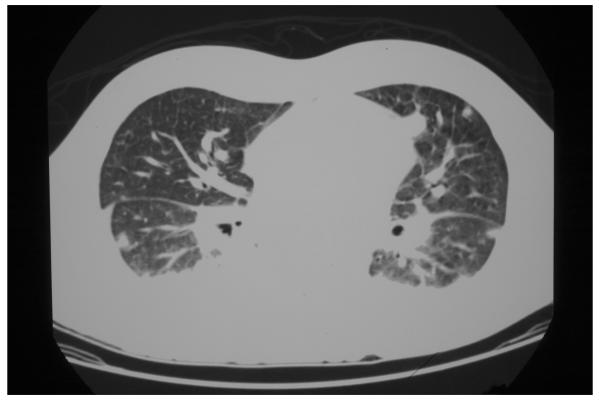

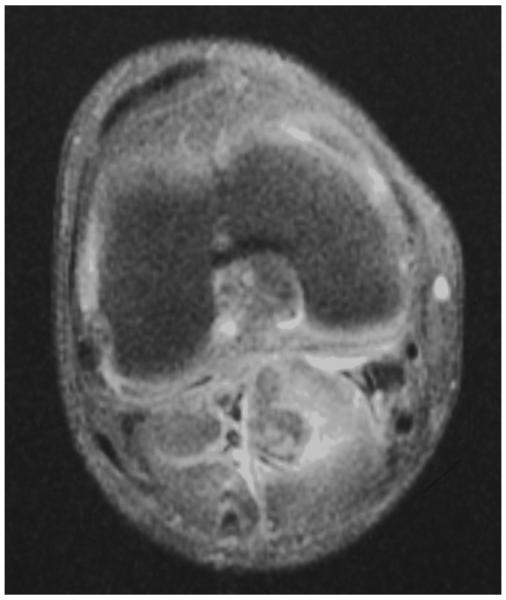

Given the patient’s presenting symptoms, a CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was performed, which revealed multiple lung lesions (12-22 mm in diameter) consistent with septic emboli (figure 1); abdominal images were unremarkable. An ultrasound of the right lower extremity was negative for a deep venous thrombosis, but an MRI revealed pyomyositis and fasciitis involving the gastrocnemius muscle (figure 2). Antibiotics were modified to pipercillin-tazobactam and levofloxacin. The patient was emergently taken to the operating room for debridement of the popliteal space and calf musculature which revealed a large abscess; pathologic evaluation showed acute and chronic inflammation of the fascia, as well as focal suppurative necrosis of the gastrocnemius muscle. An arthroscopic evaluation of the knee was unremarkable.

Figure 1.

CT scan of the chest demonstrating multiple septic pulmonary emboli.

Figure 2.

MRI of the lower extremity revealed pyomyositis and fasciitis involving the right gastrocnemius muscle.

Blood cultures and the wound culture grew Fusobacterium necrophorum. Ampicillin-sulbactam was initiated, and the follow-up blood cultures were negative. After five days of intravenous therapy, the patient defervesced. Echocardiography showed an ejection fraction of 50-55%, with no evidence of vegetations. The patient was discharged after one week of hospitalization, having received a total of 2 ½ weeks of intravenous antibiotics, followed by two weeks of oral amoxicillin-clavulanate. The patient fully recovered without sequelae.

Discussion

The first case of human necrobacillosis was reported in 1900 by Courmont and Cade [1]. This was followed by a report in 1936 by Lemierre, which identified a series of patients with Fusobacterium spp. infections; since this report, the eponym “Lemierre’s syndrome” has been used to describe Fusobacterium spp. infections of the internal jugular vein complicated by metastatic abscesses [2]. In both original and recent case descriptions, most patients had an antecedent pharyngotonsillitis presenting as a sore throat and pharyngeal hyperemia. In a recent review among 87% of cases, the primary source of infection was the palatine tonsils and peritonsillar tissue [3].

Infection typically occurs in distinct stages beginning with pharyngitis followed by local invasion into the pharyngeal space leading to thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein. Timing of the second stage is variable, but usually occurs within one week. Patients with Lemierre’s syndrome may have a proceeding bacterial or viral (e.g., infectious mononucleosis) pharyngitis, which may contribute to the translocation of the Fusobacterium spp. into the deep spaces of the neck. The third stage of infection is metastatic spread, most commonly to the lungs (80%) followed by the joints (17%); occasionally, the liver, spleen, bones, kidneys, and meninges are involved [3]. Today, the term “Lemierre’s syndrome” is used to describe Fusobacterium spp. infections originating not only in the pharynx, but in any structure in the head and neck (e.g., otitis, sinusitis, mastoiditis, parotitis, odontogenic infection, or facial skin infection) [4].

Most cases of classic Lemierre’s syndrome occur in young, otherwise healthy, adults, ages 16-23 years, with a propensity for development among males [5]. Fusobacterium spp. infections have also been increasingly reported as a cause of opportunistic infections among immunocompromised hosts and patients undergoing surgery [6]. Necrobacillosis may occur in association with a primary infection of the skin, genitourinary or gastrointestinal systems [7], as F. necrophorum is part of the normal flora of these areas as well as in the oropharynx. Bacteremia may occur when host defenses are compromised and the organism penetrates the mucosal surfaces such as cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy who develop mucositis.

Our patient was a young, immunocompetent male who presented with pyomyositis and fasciitis of his lower extremity. The origin of his Fusobacterium spp. infection remains unclear (as in 8% of cases) [3]. Most likely our patient had pharyngitis that had resolved by the time of presentation; some cases of necrobacillosis occur several weeks after the resolution of the pharyngitis. In addition, local examination findings suggesting jugular vein involvement may be subtle or absent at clinical presentation [8]. An alternative, but less likely, explanation in our case is that the bacteria could have been introduced through the skin in his calf area; however, the patient denied a history of skin abrasions or trauma. His abdominal complaints may have signified an initial gastrointestinal site of infection, but he had no risk factors such as a prior surgical procedure or gastritis that may have contributed to mucosal invasion. Of note, abdominal pain often (50% of cases in one series) accompanies Fusobacterium spp. bacteremia [3, 4]. In our case, there were no “classic” clinical manifestations to suggest a Fusobacterium spp. infection was evident. A recent review found that the first clue to the diagnosis of necrobacillosis in 70% of cases was a positive blood culture, rather than through clinical information [3].

We searched the English literature (MEDLINE, 1950-2006; EMBASE 1980-2006) for cases of pyomyositis due to Fusobacterium spp. using the search terms “Fusobacterium” or “Lemierre’s” and “pyomyositis” or “myositis”. Four cases with detailed clinical information have been published in the literature, all of which occurred in association with an adjacent septic joint (most frequently the hip, shoulder, or knee) [9-12], and all were due to F. nucleatum. One additional case of pyomyositis was reported, but the organism was only identified by gas liquid chromatography and not by cultures from the wound [13]. Our case is unique in that there was no evidence on arthroscopic examination or synovial fluid cultures of a concurrent septic arthritis and that the organism was the more virulent species of Fusobacterium, F. necrophorum.

Diagnosis is usually established by blood and wound cultures that demonstrate F. necrophorum; anaerobic cultures are required for growth of this organism. Laboratory data may reveal leukocytosis (75%), thrombocytopenia (24%), increased bilirubin (19%), or hematuria (6%) [3]; elevated liver function tests and creatinine have also been described [8, 14]. Chest radiography may show a cavitating pneumonia, pulmonary infiltrates, an abscess, pleural effusions, pneumothorax, pneumatoceles, or may be normal. CT scans of the chest are more sensitive in identifying the septic emboli to the lungs.

Effective antibiotics against Fusobacterium spp. include penicillins, cephalosporins, metronidazole, clindamycin, chloramphenicol, and tetracyclines. Since ß-lactamase production may occur [15], therapy with penicillin alone should be avoided. Furthermore, these infections may be polymicrobial in nature. Antibiotic options include an intravenous broad-spectrum β-lactamase-resistant agent (e.g., aminopenicillins), penicillin with metronidazole, or clindamycin. Despite appropriate antibiotics, fevers may persist for days given the endovascular nature of the infection and concurrent necrotic abscesses, as demonstrated by our case [4].

The duration of antibiotic treatment is poorly defined. Most reports recommend a three- to six-week course. Initial treatment should utilize intravenous antibiotics until the patient is afebrile and clinically improved [4]. Anticoagulation for thrombophlebitis is generally not recommended unless propagation of the clot towards the cavernous sinus is noted [4, 8]. Occasionally, thrombectomy and IJV ligation is necessary in cases of ongoing septic embolization, despite antimicrobial therapy. Surgical evacuation of necrotic abscesses is recommended to speed resolution of the infection.

The mortality rate in the pre-antibiotic era was almost universal, with most patients dying within 7-15 days of presentation [2]. The mortality rate remains substantial (6-18%), but most cases have a favorable outcome when appropriate therapy is administered [3, 4, 16].

Prevention of invasive infection may be accomplished by treating the initial pharyngitis before involvement of the internal jugular vein. Epidemiologically, the number of invasive Fusobacterium spp. infections decreased after the introduction of antibiotics in the 1940s and 1950s, but have recently risen, as fewer physicians now treat non-streptococcal pharyngitis cases with empiric antibiotics in an attempt to diminish the spread antimicrobial resistance [5, 14]. The rate of occurrence remains overall low, with estimates of 0.9-2.3 cases per million per year in Europe [17, 18].

This report serves to remind clinicians to consider a Fusobacterium spp. infection among patients with classic presentations of Lemierre’s syndrome as well as among infectious processes with septic embolic phenomena. Although necrobacillosis has been referred to as the “forgotten disease,” it remains an important diagnosis for all clinicians to recognize and treat.

Footnotes

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the United States Government.

Conflict of interest: None.

Financial support: None.

References

- 1.Courmont P, Cade A. Sur une septico-pyohemie de I’homme stimulant la peste et causee par un strepto-bacille anaerobie. Archives de Medecine Experimentale et d’Anatomi Pathologique. 1900;12:393–418. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemierre A. On certain septicaemias due to anaerobic organisms. Lancet. 1936;1:701–3. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chirinos JA, Lichtstein DM, Garcia J, Tamariz LJ. The evolution of Lemierre syndrome. Medicine. 2002;81:458–65. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200211000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kristensen L Hagelskjaer, Prag J. Human necrobacillosis, with emphasis on Lemierre’s syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:524–32. doi: 10.1086/313970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brazier JS. Fusobacterium necrophorum infections in man. Rev Med Microbiol. 2002;13:141–9. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-51-3-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epaulard O, Brion JP, Stahl JP, Colombe B, Maurin M. The changing pattern of fusobacterium infections in humans: recent experience with fusobacterium bacteraemia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:178–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alston JM. Necrobacillosis in Great Britain. Br Med J. 1955;2:1524–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4955.1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golpe R, Marin B, Alonso M. Eponyms in medicine revisited: Lemierre’s syndrome (necrobacillosis) Postgrad Med J. 1999;75:141–4. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.75.881.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chryssagi AM, Brusselmans CB, Rombouts JJ. Septic arthritis of the hip due to Fusobacterium nucleatum. Clin Rheumatol. 2001;29:229–31. doi: 10.1007/s100670170072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonzalez-Gay MA, Sanchez-Andrade A, Cereijo MJ, Pulpeiro JR, Armesto V. Pyomyositis and septic arthritis from Fusobacterium nucleatum in a nonimmunocompromised adult. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:518–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolf RF, Konings JG, Prins TR, Weits J. Fusobacterium pyomyositis of the shoulder after tonsillitis. Report of a case of Lemierre’s syndrome. Acta Orthop Scand. 1991;62:595–6. doi: 10.3109/17453679108994504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beaver BR. Fusobacterium nucleatum pyomyositis. Orthopedics. 1992;15:208–11. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19920201-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pickering MC, Barkham T, Mason JC, Shaunak S, Davies KA. Bilateral gluteal abscesses as a unique manifestation of Fusobacterium septicaemia. Rheumatol. 2000;39:224–5. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bliss SJ, Flanders SA, Saint S. A pain in the neck. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1037–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcps032253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein EJ, Summanen PH, Citron DM, Rosove MH, Finegold SM. Fatal sepsis due to a beta-lactamase-producing strain of Fusobacterium nucleatum subspecies polymorphum. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:797–800. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.4.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu ACY, Argent JD. Necrobacillosis — a resurgence? Clin Radiol. 2002;57:332–8. doi: 10.1053/crad.2001.0806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones JW, Riordan T, Morgan MS. Investigation of postanginal sepsis and Lemierre’s syndrome in the South West peninsula. Comm Dis Pub Health. 2001;4:278–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hagelskjaer LH, Prag J, Malczynski J, Kristensen JH. Incidence and clinical epidemiology of necrobacillosis, including Lemierre’s syndrome in Denmark 1990-1995. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;17:561–5. doi: 10.1007/BF01708619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]