Abstract

To minimize the possibility of developing lethal colorectal cancer (CRC) in ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s colitis, patients are usually enrolled in a program of dysplasia surveillance. The success of a surveillance program depends on the identification of patients with dysplasia and timely referral for colectomy. While a number of issues might stand in the way of a surveillance system achieving its maximal effect (less than ideal agreement in the interpretation of biopsy specimens, sampling error by endoscopists, delays in referral to surgery, and patient drop-out among others), circumstantial evidence supports the concept that colonoscopic dysplasia surveillance is an effective means of reducing CRC mortality and morbidity while minimizing the application of colectomy for cancer prevention. This review critically appraises key issues in the diagnosis and management of dysplasia in UC and Crohn’s disease as well as adjunct efforts to prevent CRC in inflammatory bowel disease.

Keywords: ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, colorectal cancer, dysplasia, DALM, chemoprevention

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is among the most feared long-term complications of ulcerative colitis (UC). Since the publication of a landmark report suggesting that the finding of dysplasia in a blind mucosal biopsy of the rectum correlated with the presence of invasive cancer elsewhere in the colon,1 experts have come to advocate serial endoscopic examinations with nontargeted biopsies to exclude the presence of dysplasia as a means of stratifying UC patients by risk status for the development of CRC. This practice, colonoscopic dysplasia surveillance, serves 2 main purposes: (1) minimization of CRC morbidity and mortality, and (2) reduction of the number of colonic resections in dysplasia-negative patients. Identification of dysplasia and timely referral for colectomy are central to the practice of dysplasia surveillance in patients with UC.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Colorectal Cancer in IBD

Essential to the concept of surveillance in patients with long-standing, extensive colitis are a number of features that distinguish colitis-related CRC from sporadic CRC. These include:

Increased incidence of CRC in patients with chronic colitis relative to the general population.

Increased frequency of multiple synchronous malignancies in colitis-related CRC relative to sporadic CRC.

The absence of adenomatous polyps always preceding the appearance of a malignant neoplasm in many cases of colitis-associated neoplasia.

The rate at which colitic mucosa progresses to dysplasia, and ultimately to CRC, is unknown but is believed to be more rapid than the progression of adenomas to CRC in the non-IBD population.

The presence of a generalized “field effect” in which all colitic mucosa is at high risk for malignancy because of diffuse clonal molecular and genetic changes.

Based on these features and with the advent of relatively easy and available fiber-optic and now video colonoscopy, the practice of dysplasia surveillance is now common-place. Using currently available equipment, endoscopists should obtain both targeted (lesion-directed) and nontargeted biopsies of the colon and rectum. In general, if dysplasia is present and incompletely removed by usual endoscopic maneuvers, the patient is categorized as high risk, and a colectomy should be recommended. If biopsy specimens at colonoscopy show no dysplasia, then the patient is categorized as low risk, and repeat colonoscopy in 1 to 2 years is recommended. The diagnosis of dysplasia in colitis is a combined effort of the endoscopist and the pathologist, with the inherent limitations of each participant (patient, endoscopist, and pathologist) representing critical points at which the limitations of a system of surveillance may go awry. Patient-related features such as scheduling endoscopic procedures and adherence to prescribed medications are critical as well.

Although the association between UC and CRC is well established,2 documentation of an association between CRC and Crohn’s has only recently been appreciated. Unfortunately, many studies prior to the mid-1990s (including both referral center- and population-based cohorts) sought to determine the risk of CRC in all Crohn’s patients, without adjusting for variables such as the absence of colonic disease or a history of colonic resection.3-6 After restricting analyses of the relationship between Crohn’s disease and CRC to subjects with Crohn’s colitis who had not had a colectomy, an increased CRC incidence was noted.4,7-10 It should be noted that even without adjustments for disease location or duration, the largest population-based study to date, by Bernstein and colleagues, demonstrated a significant increase in CRC incidence for all Crohn’s patients, one that was equal to the risk incurred by UC, with incidence risk ratios of 2.64 and 2.75, respectively, relative to the general population.11 A recent meta-analysis confirmed this association.12

Stratification of IBD Patients by Risk Factors

The duration and extent of colitis are well-established risk factors for the development of cancer in UC. Patients with greater than 10 years of disease and those with extensive disease (pancolitis) are at highest risk. The incidence rate increases with each successive decade of disease activity, with cumulative probabilities of 2% at 10 years, 8% at 20 years, and 18% at 30 years,13 although recent data suggest14-17 that these meta-analysis-derived rates may represent an overestimate of the true risk. These new data come from an era that includes better methods of surveillance, more widespread use of medicines that control inflammation, and other variables that might attenuate the risk of CRC in IBD. Although there is variation among studies with regard to the criteria used to define duration of disease, the CCFA Consensus Conference18 and the British Society of Gastroenterology19 suggest that screening and surveillance for dysplasia and cancer should begin after 8 years of disease.

The anatomic extent of colitis is also a clinically important risk factor for CRC in IBD.13,20 Patients with ulcerative proctitis are not considered at increased risk of CRC. Patients with left-sided UC or those with more proximal disease are at higher risk than is the general population.20 Patients with left-sided disease or pancolitis have therefore been recommended to undergo endoscopic surveillance. As mentioned above, patients with Crohn’s colitis but without prior colectomy also harbor an increased risk of CRC.9 Based on the evidence supporting surveillance in patients with leftsided ulcerative colitis, the first published Crohn’s colitis surveillance case series chose to include patients with one-third or more of the colon involved.21 In this study, 259 patients with Crohn’s colitis were entered into a surveillance colonoscopy program. Dysplasia or cancer was identified in 16% of patients, including 10 with indefinite dysplasia, 23 with low-grade dysplasia, 4 with high-grade dysplasia, and 5 with cancer. It is now recommended that CD patients with one third or more of the colon involved, like UC patients, and with 8 years or more of chronic colitis enroll in an endoscopic surveillance program.18

Patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) are a notable exception to the practice of limiting surveillance to patients with 8 or more years of disease and at least one third of the colon involved. Because of the heightened risk of CRC in these patients, surveillance is recommended at diagnosis and yearly after a diagnosis of PSC is rendered.22 Those PSC patients without a known diagnosis of IBD are recommended to undergo a diagnostic colonoscopy with biopsies in order to determine if they have subclinical evidence of colitis. Patients with known UC or Crohn’s colitis who later develop PSC should initiate yearly surveillance after their initial PSC diagnosis is established.

Other recently identified risk factors for CRC in IBD include early age of onset of colitis,20 family history of colorectal cancer,23 and severity of microscopic inflammation.24,25 In a study of 136 controls and 68 patients with UC-associated CRC by Rutter et al, multivariate analysis demonstrated that a higher degree of histologic inflammation was associated with an increased risk of developing CRC (odds ratio, 4.7; P < 0.001).25 Although an earlier study suggested an increased risk of cancer in patients with back-wash ileitis, a subsequent study did not confirm this association.26,27 Despite these clinically important associations, none have yet to be incorporated into surveillance recommendations but do raise concern when assessing individual patient risk.

EFFECTIVENESS OF SURVEILLANCE

At present, no randomized studies have documented a reduction in the risk of developing, or dying from, CRC by surveillance colonoscopy. An evidence-based review of the previous published literature (1966-2005), from the Cochrane library, concluded there was no clear evidence that surveillance colonoscopy prolongs survival in patients with extensive UC.28 However, there was evidence that cancers tended to be detected at an earlier stage in patients who underwent surveillance and that these patients had a correspondingly better prognosis, although lead-time bias may have contributed substantially to the apparent statistical benefit. Finally, the authors stated there is indirect evidence that surveillance is likely to be effective in reducing the risk of death from IBD-associated CRC and also indirect evidence that it may be cost effective. At present, despite a lack of evidence from randomized controlled trials, surveillance colonoscopy is still considered the best and most widely used method to detect dysplasia and cancer in IBD patients.

DETECTION OF DYSPLASIA

Cancer develops through a chronic inflammation-dysplasia-cancer pathway. Therefore, patients are entered into a surveillance program in order to detect neoplastic alterations (dysplasia) before the diagnosis of cancer. A number of practical features contribute to the fidelity of the surveillance system.

Gastroenterologist-Related Issues in Surveillance of IBD Patients for Dysplasia

Gastroenterologists should identify “at-risk” IBD patients, enroll them in a surveillance program, examine the colorectal epithelium at each surveillance colonoscopy, tailor management to the individual patient based on the pathologic findings, and ensure that patients return for follow-up examinations.

A group of investigators from Seattle estimated that to exclude dysplasia in colonic mucosal biopsies with 95% confidence, at least 56 nontargeted jumbo-forceps biopsies need to be obtained at each endoscopic surveillance examination. In that study, 90% confidence was achieved with 33 biopsies.29 Implicit in these data is the notion that fewer biopsies may result in the development of interval cancers between surveillance examinations. Because of the large surface area of the colon, even 33 jumbo-forceps biopsies in aggregate constitute only a tiny fraction of the colonic epithelium.

Sampling error continues to be a limitation with regard to surveillance of patients with IBD. Although no systematic study has estimated the impact of sampling error on surveillance, there is little doubt that undersampling occurs in routine clinical practice. For instance, in a 1999 questionnairebased study from the United Kingdom, more than 50% of surveyed gastroenterologists reportedly obtained fewer than 10 colonic mucosal biopsies per endoscopic surveillance examination.30 In an accounting of actual performance based on the number of specimens obtained for histologic review, Ullman noted that only 18% of surveillance examinations in subjects with extensive colitis yielded 20 or more mucosal biopsy specimens.31 In a more recent questionnaire-based study from 2004 by Rodriguez et al, 54% of gastroenterologists reported obtaining at least 31 biopsy specimens during surveillance colonoscopy.32 Whether limited biopsy practices result in a meaningful number of surveillance failures has yet to be determined. For instance, Rutter and colleagues noted that the appearance of cancer after a negative prior examination may reflect either rapid neoplastic growth or a false-negative examination from a previous surveillance examination.17 Therefore, it is essential that clinicians provide adequate tissue for pathologic evaluation. An international consensus panel agreed that a minimum of 32 biopsies should be performed at each surveillance colonoscopy by obtaining 4-quadrant biopsies every 10 cm, with each quartet placed in a separate specimen jar. In addition, separate jars should be used for raised or suspicious lesions.18 It has been suggested that additional biopsies be obtained from the distal colon given the propensity to develop dysplasia and CRC in this area. From a practical point of view, obtaining 6 samples from each of the 6 segments of the colon (right colon, transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, and proximal and distal rectum) has been employed by some experts.

In an effort to overcome the issue of sampling error, newer advanced endoscopic techniques have evolved. The improved optics of video chip technology has likely resulted in more frequent identification of polypoid lesions in patients with IBD. For instance, in a study of 110 neoplastic lesions in 56 patients in a retrospective review of 525 patients with IBD in their surveillance program, Rutter et al noted that 77% were macroscopically visible, with only 23% “flat” (or at least not reported as grossly visible). In another study of 622 patients, by Rubin and colleagues, dysplasia was visible in 38 of 65 surveillance-detected dysplastic lesions in 46 patients.33

The use of chromoendoscopy has been implemented by many centers for use in colitis-related surveillance. Chromoendoscopy can improve the detection of subtle colonic lesions, raising the sensitivity of endoscopic examinations and improving the characterization of lesions, which also increases the specificity of the examination. Additionally, crypt architecture can be categorized by evaluating the pit pattern, which aids in differentiation of neoplastic from non-neoplastic changes and enables the performance of targeted biopsies. Several investigators have documented an increased yield of dysplasia detection on a per-patient basis using either diluted methylene blue or indigo carmine spray.34-36 In the first published study of chromoendoscopy in IBD, Kiesslich et al reported 165 patients with long-standing UC who were randomized to conventional colonoscopy or colonoscopy with chromoendoscopy using 0.1% methylene blue. More targeted biopsies were possible, and significantly more dysplastic lesions were detected in the chromoendoscopy group (32 vs. 10; P = 0.003). In a second “back-to-back” colonoscopy study, 100 patients with long-standing UC underwent conventional colonoscopy with both random and directed biopsies followed by spraying of the mucosa with 0.1% indigo carmine, and then directed biopsies were obtained. In the pre-dye spray colonoscopy, there was no dysplasia in 2904 nontargeted biopsies. Forty-three mucosal abnormalities were identified in 20 patients, of which 2 were dysplastic. After spraying, an additional 114 abnormalities were identified in 55 patients, of which 7 were dysplastic. The authors concluded that careful mucosal examination aided by pancolonic chromoendoscopy and targeted biopsies of suspicious lesions may be a more effective method of surveillance compared to obtaining multiple nontargeted biopsies. In the first reported U.S.-based chromoendoscopy series, Marion and colleagues found that nontargeted biopsies identified dysplasia in 3 of 115 patients compared with in 9 of 115 with dysplasia identified in targeted lesions with normal white light. An additional 10 patients who were dysplasia free by white light methods were found to have dysplasia after 0.1% methylene blue spray.37 An atlas of chromoendoscopic images in IBD has been published recently.38 Longitudinal studies of chromoendoscopy will be needed to determine if the incidence of CRC is reduced in patients undergoing surveillance with this technology.

Newer endoscopic techniques may ultimately be found to increase the yield of identifying dysplasia in patients with colitis. These include narrow-band imaging39 and endomicroscopy. A recent randomized controlled trial of confocal chromoscopic endomicroscopy was associated with a 2.5-fold increase in the detection rate of intraepithelial neoplasia (P = 0.001) as well as high-grade dysplastic lesions (P = 0.001) in patients with UC, compared to standard chromoendoscopy with methylene blue.40

Pathologist-Related Issues in Diagnosis of Dysplasia

Pathologic interpretation of specimens for evaluation of dysplasia constitutes a critical step in endoscopic surveillance programs. Ultimately, it is the pathologist’s interpretation of mucosal biopsy specimens that distinguishes high-risk from low-risk populations and triggers recommendations for either continued surveillance or proctocolectomy. Thus, accurate diagnosis of dysplasia is the mainstay of the surveillance process. Currently, dysplasia is separated into 3 distinct categories: negative for dysplasia, indefinite for dysplasia, and positive for dysplasia (low or high grade).41 While endeavoring to minimize disagreement in both terminology and interpretation, rates of agreement using this grading system are only fair among both expert and community pathologists.42 Crude rates of agreement among experts have ranged from 42% to 72%; kappa values, where there is a correction for chance agreement, have remained fair for both experts and community pathologists as well.42-45 Unfortunately, rates of agreement are lowest for the indefinite for dysplasia and low-grade dysplasia categories.42,46 Based on these data, the CCFA consensus guidelines and the U.S. Multisociety Task Force strongly recommend that a second examination of the biopsies should be performed by an independent pathology expert prior to definitive treatment.18,47

Patient-Related Issues in Diagnosis of Dysplasia

The patient’s role in surveillance is the most critical but the least studied. The only aspects of the dysplasia surveillance process required of the patient are to adhere to the scheduled examinations and to consider the management options recommended by his or her gastroenterologist. Sadly, anecdotal evidence culled from published reports from surveillance-related literature points to the hazards of dropout of patients in whom advanced-stage cancers have occurred.48-51 What factors might predict dropout or nonadherence to scheduled surveillance remain unknown and merit additional study. Patient dropout continues to be a problematic clinical issue. Patients must be counseled not only about the risk of developing CRC but also regarding the risk of developing cancer if they drop out of the surveillance program. Patients should also be informed that cancer may develop without previous detection of dysplasia.22 Reminder cards or letters should be sent to patients before office visits to better ensure timely surveillance examinations.

MANAGEMENT OF DYSPLASIA

Endoscopically, dysplasia may be flat or raised. Flat dysplasia is further characterized as either unifocal or multifocal. The term dysplasia-associated lesion or mass (DALM) has been applied to the raised dysplastic lesions seen on colonoscopy. In a study by Blackstone et al of 12 patients with DALMs, 7 were found to be malignant.52 However, many of the patients in the Blackstone study had symptoms related to these lesions, many of which were quite obviously symptomatic cancers whose endoscopic biopsies were only representative of the surface of the lesion. DALMs appear endoscopically similar to sporadic adenomas, and these are referred to as adenoma-like DALMs. Non-adenoma-like DALMs are lesions not endoscopically amenable to resection.

Adenoma-like DALMs

An essential issue in the management of adenoma-like DALMs is whether a dysplastic lesion can be safely removed in total endoscopically. Raised lesions are commonly encountered during surveillance colonoscopy.53 In a retrospective study of 56 patients with dysplasia from St. Marks, 50 patients (89.3%) had macroscopically detectable neoplastic lesions. The authors concluded that most dysplastic lesions encountered during surveillance were “visible.”54 In a similar study from the United States, Rubin and colleagues demonstrated that 38 of 65 dysplastic lesions (58.5%) and 8 of 10 cancers (80.0%) were visible endoscopically.33 The management of adenoma-like DALMs depends on the size and appearance of the lesion and the ability of the endoscopist to detect and remove such lesions in their entirety at colonoscopy.

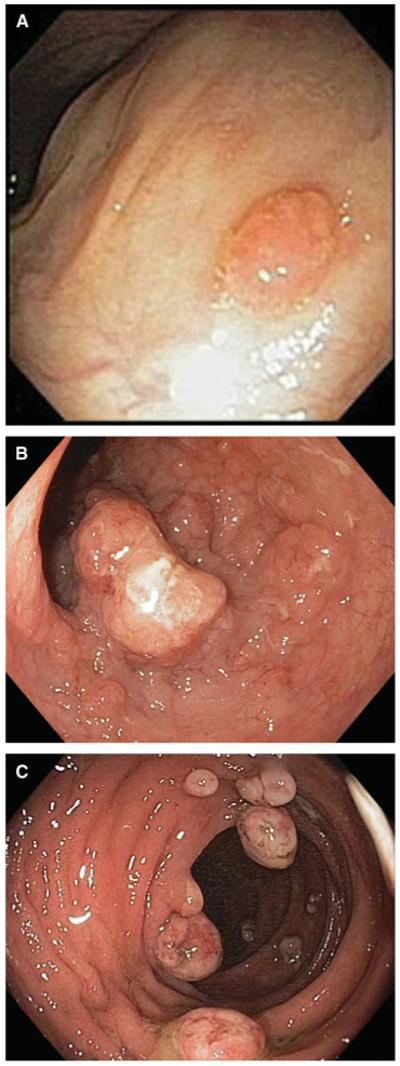

Early isolated reports described successful conservative management of small polypoid dysplastic lesions in patients with ulcerative colitis.46,55,56 Since then, Odze and colleagues demonstrated that adenoma-like DALMs could be identified and removed by standard endoscopic techniques with little or no risk of subsequent malignancy. In that study, raised dysplastic lesions were characterized as those that had endoscopic features similar to sporadic adenomas (adenoma-like DALMs; Fig. 1A) and those that were sessile, irregular, or ulcerated (non-adenoma-like DALMs; Fig. 1B). In the absence of flat dysplasia elsewhere in the colon, the risk of patients who had undergone polypectomy developing dysplasia or colorectal cancer was extremely low over an 82-month follow-up period.57,58 Rubin and colleagues demonstrated similar results in a cohort of patients followed for a mean of 49 months.59 One essential caveat to the practice of endoscopic treatment of small adenoma-like DALMs is the requirement that they be removed in their entirety. A recent retrospective study by Vieth and colleagues60 showed a high rate of progression to cancer in patients with raised dysplasia that were merely biopsies, and not completely removed. If polypoid lesions can be completely removed and the rest of the colon is dysplasia-free, it appears safe to pursue a non-operative course of continued surveillance regardless of whether there is high-grade dysplasia in the resected lesion.

FIGURE 1.

(A) Adenoma-like DALM. (Courtesy of Jerome Waye, MD). (B) Non-adenoma-like DALM. (C) Inflammatory polyps.

Most other polypoid lesions encountered during surveillance endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease patients are inflammatory polyps (pseudopolyps). These polyps can have several different endoscopic appearances, do not have significant malignant potential, and thus do not need to be resected (Fig. 1C). However, the presence of multiple inflammatory polyps has been shown to be a predictor of the subsequent development of CRC, presumably because this is indicative of previous severe colonic injury and multiple inflammatory polyps increases the difficulty of performing surveillance colonoscopy. It is important that efforts be undertaken to disseminate diagnostic and management guidelines of polypoid lesions in IBD to gastroenterologists.61

Flat High-Grade Dysplasia

In a systematic review, 42% of patients with flat high-grade dysplasia (HGD) were found to have CRC at the time of colectomy.62 A recent follow-up study from the St. Mark’s group documented a 45% rate of CRC when patients underwent immediate colectomy.17 Curiously, Bernstein’s systematic review documented a crude progression rate of 32% for patients with HGD who pursued a nonoperative course; the actuarial rate of progression of this group was not reported.62 Based on these and related studies, colectomy has been and remains the treatment of choice for patients diagnosed with incompletely resected HGD or with HGD found on a nontargeted biopsy.

Flat Low-Grade Dysplasia

There is less certainty regarding the natural history of flat low-grade dysplasia (LGD). In 1 study, Connell et al demonstrated that low-grade dysplasia had a substantially worse outcome, showing a 5-year rate of progression to HGD or CRC of 16% to 54%.63 Bernstein and colleagues detected a 19% rate of CRC for patients with LGD who underwent immediate colectomy in a critical review of the surveillance literature.62 These studies suggest a more ominous prognosis for UC patients with LGD than previously believed. However, some reports have suggested a low rate of progression to HGD or cancer.64-66 Others have noted a more aggressive and unpredictable course, with rates of CRC at immediate colectomy near 20% and 5-year rates of progression to HGD or CRC of greater than 50%. Some studies have shown the development of node-positive CRC without intervening HGD and following dysplasia-free surveillance examinations less than a year before the appearance of the malignancy.51,62,63,67 A recent meta-analysis concluded that the positive predictive value of CRC for patients with flat LGD was 22% and that patients with LGD carried a risk for CRC 9 times that of patients in surveillance who were dysplasia free.68 It is also worth noting that in 1 study, unifocal LGD was as likely to progress to HGD or cancer as was multifocal LGD. No clinical features were predictive of subsequent progression, and progression to node-positive CRC may occur in patients with a prior history of flat LGD within 12 months of a subsequent dysplasia-free surveillance examination.67 Finally, a recent publication in the pathology literature identified low-grade tubuloglandular adenocarcinoma, a finding responsible for 11% of IBD-associated adenocarcinomas, in which superficial LGD was associated with underlying invasive adenocarcinoma.69 This finding further supports colectomy as the treatment of choice for patients with flat LGD.

Indefinite for Dysplasia

Epithelial regeneration and repair, especially in the setting of active inflammation, may result in atypia that can be difficult to distinguish from true dysplasia. These cases are termed “indefinite for dysplasia.”70 Patients whose biopsy specimens are indefinite for dysplasia are a poorly studied group of IBD patients. In a 1991 report by Nugent et al, 20 patients with biopsies considered “indefinite” were followed for an unspecified length of time. Three subjects developed high-grade dysplasia, 1 of whom was discovered to have an adenocarcinoma at the time of colectomy.71 More recently, Ullman and colleagues noted a 9.0% 5-year progression rate to HGD or CRC among 56 patients with biopsies considered indefinite for dysplasia. This rate of progression was intermediate between patients with no dysplasia and those with flat LGD.72 The CCFA consensus guideline recommends that patients with biopsies indefinite for dysplasia be followed with annual surveillance examinations.

No Dysplasia

IBD patients without histologic evidence of dysplasia in their colon biopsies have the lowest rates of progression to cancer. For instance, Ullman et al reported a 1.1% incidence of colorectal cancer at 5 years in an analysis of UC 311 patients.72 Examinations every 1-2 years is suggested by the CCFA Consensus conference for this group of patients.18

CHEMOPREVENTION

Similar to investigations of sporadic CRC, investigators are actively investigating medications that may help decrease the risk of developing CRC in UC. Unfortunately, most of these studies are retrospective. As is often the case in retrospective studies, the dose and duration of use that define exposure are often arbitrarily chosen. The reader is referred to several recent review articles for additional information on chemoprevention in IBD.73,74

Mesalamine-Based Agents

Sulfasalazine and newer 5-ASA products have been investigated for their chemopreventive effect, mainly by post hoc secondary analyses, and have yielded conflicting results. In a study designed to investigate the effect of supplemental folic acid on CRC risk, sulfasalazine use was found to have a positive (i.e., predisposing) effect on the development of CRC (slightly but not significantly higher rates of CRC in the exposed group); sulfasalazine-allergic patients, however, were noted to have a substantially lower risk of developing CRC.75 Subsequently, Pinczowski and Eaden demonstrated a protective effect for sulfasalazine or mesalazine.76,77 Tung et al78 failed to demonstrate a meaningful protective effect, but this study was limited to high-risk PSC patients. A number of additional studies with a variety of definitions for exposure have now been performed with conflicting results. Some have shown benefit with exposure to mesalamine-based agents,79,80 whereas others have been less optimistic.81,82 A systemic review by Velayos and colleagues concluded that mesalamine is chemopreventive. However, this observation must be interpreted with caution because of the heterogeneity of the methods employed in the studies (case-control, retrospective cohort, secondary analyses). In that review, a protective association between use of 5-aminosalicylates and CRC was noted, with an odds ratio of 0.51 whether the measured outcome was CRC or either CRC or dysplasia.83 Studies that have evaluated the effect of histologic inflammation on the subsequent development of dysplasia or CRC have failed to demonstrate a chemopreventive effect for mesalamine-based agents independent of inflammation in multivariate modeling.24,25 A recent cohort study of patients enrolled in a surveillance system detected no chemopreventive effect for mesalamine.72 Given the disparity of the results in these studies, it remains unknown whether mesalamine-based medications constitute efficacious chemopreventive agents. However, given their utility at preventing flares in patients in remission, their use is advocated in all UC patients.

Folic Acid

Folic acid, which has been demonstrated to have a protective effect in sporadic CRC, was studied in IBD patients by Lashner et al.75,84 In neither of their studies was a significant protective effect noted, although the point estimates of risk (0.38 and 0.45) suggested the possibility of a chemopreventive effect. Given the low cost and the low risk of adverse events at conventional doses of 400 μg per day and 1 mg per day, the administration of folic acid as a chemopreventive drug should be strongly considered for all at-risk IBD patients.

Ursodeoxycholic Acid

Ursodeoxycholic acid, an exogenous bile acid used in the treatment of PSC, has also been studied as a possible chemopreventive agent in UC patients. In UC-PSC patients, an impressive chemopreventive effect has been demonstrated, with a 40% difference in neoplasia noted between the ursodeoxycholic acid-treated group (32%) and the untreated group (72%).78 This was additionally demonstrated in a randomized clinical trial of ursodeoxycholic acid in which a 74% reduction in dysplasia or CRC was noted.85 Although this issue is currently under investigation, it is unknown if this chemopreventive effect can be demonstrated in patients with UC or Crohn’s colitis who do not have PSC.

Immunomodulators

A single cohort study failed to demonstrate a chemopreventive effect of the thiopurine analogues 6-mercaptopurine and azathioprine.86 However, their utility in patients with steroid-dependent and steroid-refractory disease is undisputed and renders these agents as important forms of therapy for IBD patients. Whether mesalamine-based agents should be continued after initiation of thiopurines remains unknown. The effect of methotrexate and anti-TNF agents as chemopreventive agents remains untested.

SUMMARY

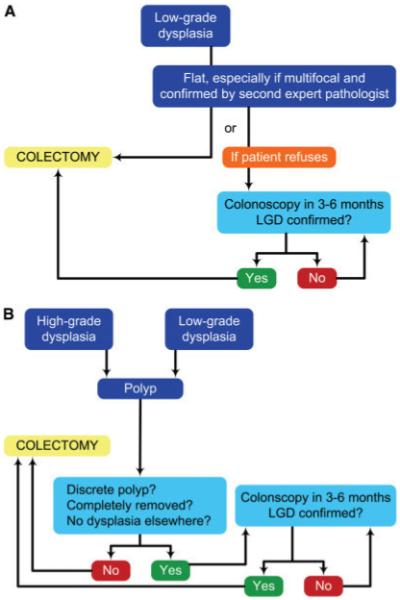

A full colonoscopy to the terminal ileum should be performed in all IBD patients 8 years after the onset of symptoms or following a diagnosis of PSC. Biopsies should be obtained throughout the colon to assess the extent of disease. For patients with extensive colitis, endoscopists should obtain 4-quadrant jumbo biopsy forceps from every 10 cm of colon or from every segment of colon with a proven history of IBD, for a minimum of 33 biopsies per examination. Four-quadrant biopsies should be obtained from all involved segments in patients with more limited disease, provided there is no history of colonic involvement in segments not previously sampled. Each quartet of biopsies should be placed in a separate specimen jar for the purpose of matching dysplasia to a specific location. Additionally, all suspicious lesions should be biopsied and, when possible, endoscopically removed for histologic analysis. This includes both white light-detected and chromoendoscopically detected lesions. All suspicious lesions should also be placed in separate jars. In the future, the use of chromoendoscopy and directed biopsies may obviate the need for random biopsies. Proper bowel preparation is of paramount importance to evaluate the mucosal surface; this is especially true for the application of either methylene blue or indigo carmine during chromoendoscopy. A proposed algorithm for the management of flat LGD as well as DALMs is shown in Figure 2A, B.

FIGURE 2.

(A) Management of flat dysplasia. (B) Management of polypoid dysplasia. (Modified from Itzkowitz, Gastroenterology 2004; Reference 22).

Colitis-related CRC remains a meaningful problem for patients with extensive and long-standing IBD.22 Conventional wisdom holds that dysplasia surveillance, despite its many potential limitations, is a useful tool in reducing CRC mortality in IBD while simultaneously minimizing unnecessary colonic resections.87 The addition of chemopreventive agents may further enhance the effect of colonoscopic surveillance. Newer techniques, especially chromoendoscopy using dye sprays to enhance the surface markings of colonic mucosa, may find a role in surveillance in the near future and obviate the need for multiple nontargeted biopsies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Morson BC, Pang LS. Rectal biopsy as an aid to cancer control in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1967;8:423–434. doi: 10.1136/gut.8.5.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crohn BB, Rosenberg H. The sigmoidoscopic picture of chronic ulcerative colitis. Am J Med Sci. 1925;170:220–228. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weedon DD, Shorter RG, Ilstrup DM, et al. Crohn’s disease and cancer. N Engl J Med. 1973;289:1099–1103. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197311222892101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gyde SN, Prior P, Macartney JC, et al. Malignancy in Crohn’s disease. Gut. 1980;21:1024–1029. doi: 10.1136/gut.21.12.1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Persson PG, Karlen P, Bernell O, et al. Crohn’s disease and cancer: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1675–1679. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90807-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gillen CD, Andrews HA, Prior P, et al. Crohn’s disease and colorectal cancer. Gut. 1994;35:651–655. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.5.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ekbom A, Helmick C, Zack M, et al. Increased risk of large-bowel cancer in Crohn’s disease with colonic involvement. Lancet. 1990;336:357–359. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91889-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillen CD, Walmsley RS, Prior P, et al. Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease: a comparison of the colorectal cancer risk in extensive colitis. Gut. 1994;35:1590–1592. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.11.1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sachar DB. Cancer in Crohn’s disease: dispelling the myths. Gut. 1994;35:1507–1508. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.11.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Munkholm P, Langholz E, Davidsen M, et al. Intestinal cancer risk and mortality in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1716–1723. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)91068-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernstein CN, Blanchard JF, Kliewer E, et al. Cancer risk in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Cancer. 2001;91:854–862. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010215)91:4<854::aid-cncr1073>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canavan C, Abrams KR, Mayberry J. Meta-analysis: colorectal and small bowel cancer risk in patients with Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1097–1104. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eaden JA, Abrams KR, Mayberry JF. The risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2001;48:526–535. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.4.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jess T, Loftus EV, Jr, Velayos FS, et al. Incidence and prognosis of colorectal dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study from Olmsted County, Minnesota. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:669–676. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200608000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masala G, Bagnoli S, Ceroti M, et al. Divergent patterns of total and cancer mortality in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease patients: the Florence IBD study 1978-2001. Gut. 2004;53:1309–1313. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.031476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lakatos L, Mester G, Erdelyi Z, et al. Risk factors for ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer in a Hungarian cohort of patients with ulcerative colitis: results of a population-based study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:205–211. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000217770.21261.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rutter MD, Saunders BP, Wilkinson KH, et al. Thirty-year analysis of a colonoscopic surveillance program for neoplasia in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1030–1038. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Itzkowitz SH, Present DH. Consensus conference: Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:314–321. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000160811.76729.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eaden JA, Mayberry JF. Guidelines for screening and surveillance of asymptomatic colorectal cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2002;51:V10–V12. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.suppl_5.v10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ekbom A, Helmick C, Zack M, et al. Ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer. A population-based study. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1228–1233. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199011013231802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedman S, Rubin PH, Bodian C, et al. Screening and surveillance colonoscopy in chronic Crohn’s colitis. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:820–826. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.22449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Itzkowitz SH, Harpaz N. Diagnosis and management of dysplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1634–1648. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nuako KW, Ahlquist DA, Mahoney DW, et al. Familial predisposition for colorectal cancer in chronic ulcerative colitis: a case-control study. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1079–1083. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70077-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta RB, Harpaz N, Itzkowitz S, et al. Histologic inflammation is a risk factor for progression to colorectal neoplasia in ulcerative colitis: a cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1099–1105. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.001. quiz 1340-1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rutter M, Saunders B, Wilkinson K, et al. Severity of inflammation is a risk factor for colorectal neoplasia in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:451–459. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haskell H, Andrews CW, Jr, Reddy SI, et al. Pathologic features and clinical significance of “backwash” ileitis in ulcerative colitis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1472–1481. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000176435.19197.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heuschen UA, Hinz U, Allemeyer EH, et al. Backwash ileitis is strongly associated with colorectal carcinoma in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:841–847. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.22434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Collins PD, Mpofu C, Watson AJ, et al. Strategies for detecting colon cancer and/or dysplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000279.pub3. CD000279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rubin CE, Haggitt RC, Burmer GC, et al. DNA aneuploidy in colonic biopsies predicts future development of dysplasia in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1611–1620. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eaden JA, Ward BA, Mayberry JF. How gastroenterologists screen for colonic cancer in ulcerative colitis: an analysis of performance. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:123–128. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(00)70405-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ullman TA, Croog V, Harpaz N, et al. Biopsy specimen numbers in the routine practice of surveillance colonoscopy in ulcerative colitis (UC) Gastroenterology. 2004;126:A–471. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodriguez SA, Eisen GM. Surveillance and management of dysplasia in ulcerative colitis by U.S. gastroenterologists: in truth, a good performance. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:1070. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rubin DT, Rothe JA, Hetzel JT, et al. Are dysplasia and colorectal cancer endoscopically visible in patients with ulcerative colitis? Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:998–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hurlstone DP, Sanders DS, Lobo AJ, et al. Indigo carmine-assisted high-magnification chromoscopic colonoscopy for the detection and characterisation of intraepithelial neoplasia in ulcerative colitis: a prospective evaluation. Endoscopy. 2005;37:1186–1192. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-921032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kiesslich R, Fritsch J, Holtmann M, et al. Methylene blue-aided chromoendoscopy for the detection of intraepithelial neoplasia and colon cancer in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:880–888. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rutter MD, Saunders BP, Schofield G, et al. Pancolonic indigo carmine dye spraying for the detection of dysplasia in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2004;53:256–260. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.016386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marion JF, Waye JD, Present DH, et al. Methylene blue spray targeted biopsies are superior to standard colonoscopic surveillance for detecting dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease patients: a prospective endoscopic trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2342–2349. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsumoto T, Iwao Y, Igarashi M, et al. Endoscopic and chromoendo-scopic atlas featuring dysplastic lesions in surveillance colonoscopy for patients with long-standing ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:259–264. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dekker E, van den Broek FJ, Reitsma JB, et al. Narrow-band imaging compared with conventional colonoscopy for the detection of dysplasia in patients with longstanding ulcerative colitis. Endoscopy. 2007;39:216–221. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hurlstone DP, Kiesslich R, Thomson M, et al. Confocal chromoscopic endomicroscopy is superior to chromoscopy alone for the detection and characterisation of intraepithelial neoplasia in chronic ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2008;57:196–204. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.131359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Riddell RH, Goldman H, Ransohoff DF, et al. Dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease: standardized classification with provisional clinical applications. Hum Pathol. 1983;14:931–968. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(83)80175-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eaden J, Abrams K, McKay H, et al. Inter-observer variation between general and specialist gastrointestinal pathologists when grading dysplasia in ulcerative colitis. J Pathol. 2001;194:152–157. doi: 10.1002/path.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dixon MF, Brown LJ, Gilmour HM, et al. Observer variation in the assessment of dysplasia in ulcerative colitis. Histopathology. 1988;13:385–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1988.tb02055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Melville DM, Jass JR, Morson BC, et al. Observer study of the grading of dysplasia in ulcerative colitis: comparison with clinical outcome. Hum Pathol. 1989;20:1008–1014. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(89)90273-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Odze RD, Goldblum J, Noffsinger A, et al. Interobserver variability in the diagnosis of ulcerative colitis-associated dysplasia by telepathology. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:379–386. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Connell WR, Lennard-Jones JE, Williams CB, et al. Factors affecting the outcome of endoscopic surveillance for cancer in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:934–944. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90216-x. see comments. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Winawer S, Fletcher R, Rex D, et al. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale-Update based on new evidence. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:544–560. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lennard-Jones JE, Morson BC, Ritchie JK, et al. Cancer surveillance in ulcerative colitis. Experience over 15 years. Lancet. 1983;2:149–152. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)90129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lynch DA, Lobo AJ, Sobala GM, et al. Failure of colonoscopic surveillance in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1993;34:1075–1080. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.8.1075. see comments. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woolrich AJ, DaSilva MD, Korelitz BI. Surveillance in the routine management of ulcerative colitis: the predictive value of low-grade dysplasia. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:431–438. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90831-i. see comments. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ullman TA, Loftus EV, Jr, Kakar S, et al. The fate of low grade dysplasia in ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:922–927. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blackstone MO, Riddell RH, Rogers BH, et al. Dysplasia-associated lesion or mass (DALM) detected by colonoscopy in long-standing ulcerative colitis: an indication for colectomy. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:366–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Friedman S, Odze RD, Farraye FA. Management of neoplastic polyps in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2003;9:260–266. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200307000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rutter MD, Saunders BP, Wilkinson KH, et al. Most dysplasia in ulcerative colitis is visible at colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:334–339. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)01710-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nugent FW, Haggitt RC, Gilpin PA. Cancer surveillance in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1241–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Medlicott SA, Jewell LD, Price L, et al. Conservative management of small adenomata in ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:2094–2098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Engelsgjerd M, Farraye FA, Odze RD. Polypectomy may be adequate treatment for adenoma-like dysplastic lesions in chronic ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1288–1294. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70278-7. discussion 1488-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Odze RD, Farraye FA, Hecht JL, et al. Long-term follow-up after polypectomy treatment for adenoma-like dysplastic lesions in ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:534–541. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00237-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rubin PH, Friedman S, Harpaz N, et al. Colonoscopic polypectomy in chronic colitis: conservative management after endoscopic resection of dysplastic polyps. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1295–1300. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vieth M, Behrens H, Stolte M. Sporadic adenoma in ulcerative colitis: endoscopic resection is an adequate treatment. Gut. 2006;55:1151–1155. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.075531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Farraye FA, Waye JD, Moscandrew M, et al. Variability in the diagnosis and management of adenoma-like and non-adenoma-like dysplasia-associated lesions or masses in inflammatory bowel disease: an Internet-based study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:519–529. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bernstein CN, Shanahan F, Weinstein WM. Are we telling patients the truth about surveillance colonoscopy in ulcerative colitis? Lancet. 1994;343:71–74. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90813-3. see comments. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Connell WR, Talbot IC, Harpaz N, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics of colorectal carcinoma complicating ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1994;35:1419–1423. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.10.1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lim CH, Axon AT. Low-grade dysplasia: nonsurgical treatment. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2003;9:270–272. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200307000-00008. discussion 273-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Befrits R, Ljung T, Jaramillo E, et al. Low-grade dysplasia in extensive, long-standing inflammatory bowel disease: a follow-up study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:615–620. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6255-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lindberg B, Persson B, Veress B, et al. Twenty years’ colonoscopic surveillance of patients with ulcerative colitis. Detection of dysplastic and malignant transformation. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:1195–1204. doi: 10.3109/00365529609036910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ullman T, Croog V, Harpaz N, et al. Progression of flat low-grade dysplasia to advanced neoplasia in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1311–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thomas T, Abrams KA, Robinson RJ, et al. Meta-analysis: cancer risk of low-grade dysplasia in chronic ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:657–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Levi GS, Harpaz N. Intestinal low-grade tubuloglandular adenocarcinoma in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:1022–1029. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200608000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Odze RD. Pathology of dysplasia and cancer in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2006;35:533–552. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nugent FW, Haggitt RC, Gilpin PA. Cancer surveillance in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1241–1248. see comments. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ullman TA, Croog V, Harpaz N, et al. Progression to colorectal neoplasia in ulcerative colitis: effect of 5-aminosalicylic acid. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.05.020. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chan EP, Lichtenstein GR. Chemoprevention: risk reduction with medical therapy of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2006;35:675–712. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Levine JS, Burakoff R. Chemoprophylaxis of colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: current concepts. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:1293–1298. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lashner BA, Heidenreich PA, Su GL, et al. Effect of folate supplementation on the incidence of dysplasia and cancer in chronic ulcerative colitis. A case-control study. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:255–259. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)90058-9. see comments. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Eaden J, Abrams K, Ekbom A, et al. Colorectal cancer prevention in ulcerative colitis: a case-control study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:145–153. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pinczowski D, Ekbom A, Baron J, et al. Risk factors for colorectal cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis: a case-control study. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:117–120. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tung BY, Emond MJ, Haggitt RC, et al. Ursodiol use is associated with lower prevalence of colonic neoplasia in patients with ulcerative colitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:89–95. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-2-200101160-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.van Staa TP, Card T, Logan RF, et al. 5-Aminosalicylate use and colorectal cancer risk in inflammatory bowel disease: a large epidemiological study. Gut. 2005;54:1573–1578. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.070896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rubin DT, LoSavio A, Yadron N, et al. Aminosalicylate therapy in the prevention of dysplasia and colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1346–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bernstein CN, Blanchard JF, Metge C, et al. Does the use of 5-aminosalicylates in inflammatory bowel disease prevent the development of colorectal cancer? Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2784–2788. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Terdiman JP, Steinbuch M, Blumentals WA, et al. 5-Aminosalicylic acid therapy and the risk of colorectal cancer among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:367–371. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Velayos FS, Terdiman JP, Walsh JM. Effect of 5-aminosalicylate use on colorectal cancer and dysplasia risk: a systematic review and metaanalysis of observational studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1345–1353. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lashner BA, Provencher KS, Seidner DL, et al. The effect of folic acid supplementation on the risk for cancer or dysplasia in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:29–32. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70215-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pardi DS, Loftus EV, Jr, Kremers WK, et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid as a chemopreventive agent in patients with ulcerative colitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:889–893. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Matula S, Croog V, Itzkowitz S, et al. Chemoprevention of colorectal neoplasia in ulcerative colitis: the effect of 6-mercaptopurine. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:1015–1021. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00738-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mpofu C, Watson AJ, Rhodes JM. Strategies for detecting colon cancer and/or dysplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000279.pub2. CD000279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]