Abstract

The goals of the present study were to examine (1) the mean-level stability and differential stability of children’s positive emotional intensity, negative emotional intensity, expressivity, and social competence from early elementary school-aged to early adolescence, and (2) the associations between the trajectories of children’s emotionality and social functioning. Using four waves of longitudinal data (with assessments 2 years apart), parents and teachers of children (199 kindergarten through third grade children at the first assessment) rated children’s emotion-related responding and social competence. For all constructs, there was evidence of mean-level decline with age and stability in individual differences in rank ordering. Based on age-centered growth-to-growth curve analyses, the results indicated that children who had a higher initial status on positive emotional intensity, negative emotional intensity, and expressivity had a steeper decline in their social skills across time. These findings provide insight into the stability and association of emotion-related constructs to social competence across the elementary and middle school years.

Keywords: trajectories, positive affect, negative affect, social competence

Developmental scientists have increasingly acknowledged the importance of the experience and expression of emotion in every-day life and its potential role in social competence. However, our understanding of developmental trajectories in children’s intensity of emotion and their implications for social competence is limited. The first major goal of the present study was to examine the degree of stability of children’s emotional intensity, expressivity, and social competence. Another major goal (which was dependent on the analyses pertaining to the first goal) was to examine associations between the trajectories of emotion and social functioning as children moved into early adolescence.

Notions of Stability

Given the goal of investigating children’s emotionality across time, the stability of these constructs was examined in two ways: (1) the rank-order of variables and (2) the mean level across time (Fraley & Roberts, 2005). Rank-order stability provides information about differential continuity (i.e., degree to which individual differences remain stable across time) whereas mean-level stability refers to change in the average level of a variable across time (De Fruyt et al., 2006). Both types of stability are useful for understanding development.

Positive and Negative Emotionality

Researchers typically view positive and negative emotionality as dimensions of temperament (Aksan et al., 1999; Rothbart & Bates, 2006), defined as a set of constitutionally based traits that are the core of personality and influence the direction of development (Rothbart & Bates, 2006). Even though temperament is usually described as having a constitutional basis, environmental influences also play a role, more so for some aspects of temperament (e.g., positive emotionality) than others (e.g., negative emotionality; Emde et al., 1992; Goldsmith, Lemery, Buss, & Campos, 1999). Thus, some aspects of temperament may be relatively malleable (Fox & Calkins, 2003; Rothbart & Bates, 2006), a finding that highlights the importance of investigating developmental trajectories.

Researchers have found that reports of positive emotion and negative emotion are distinct dimensions (Belsky, Hsieh, & Crnic, 1996; Durbin, Hayden, Klein, & Olino, 2007; Kochanska, Coy, Tjebkes, & Husarek, 1998; see Diener & Larsen, 1993). Other approaches to distinguishing between positive and negative emotions come from behavioral and neurological perspectives. For example, Gray (1987) proposed somewhat distinct two motivational systems that influence behavior—the Behavioral Activation System involved with potential rewards or positive outcomes and the Behavioral Inhibition System involved with signals of punishment and negative cues. Additionally, neuroscientists have identified brain systems that are activated when emotions are experienced and executed (Damasio, 2004) and have found differences in brain patterns between adults experiencing positive and negative emotions (see Harmon-Jones, 2003).

Positive emotional intensity and negative emotional intensity also may be differentially valued or displayed in various cultures. For example, the expression of intense positive affect has been found to be more emphasized and valued in Western cultures than in non-Western cultures (Eisenberg, Liew, & Pidada, 2001; Tsai, Chentsova-Dutton, Freire-Bebeau, & Przymus, 2002; Tsai, Levenson, & McCoy, 2006). Conversely, Tsai et al. (2006) also found that European American adults displayed less negative affect than Chinese American adults. These findings suggest that patterns of emotional intensity may differ depending on valence and culture.

In the present study, we focused on positive and negative emotional intensity as separate constructs, as well as on general emotional expressivity. Although emotional intensity and frequency of emotionality and its expression often are related (e.g., Bachorowski & Braaten, 1994; Diener, Larsen, Levine, & Emmons, 1985; Eisenberg et al., 1993), it is important to examine intensity of emotions as well as their frequency. For example, although frequency of positive emotionality is generally positively related to children’s social competence and self-regulation (e.g., Hayden, Klein, Durbin, & Olino, 2006; Lengua, 2003; Pesonen et al., 2008), there is evidence that intensity of positive emotionality is associated with low regulation and sometimes with negative social outcomes (e.g., Kochanska, Murray, & Harlan, 2000; Kochanska & Knaack, 2003; Oldehinkel et al., 2004; Rydell, Berlin, & Bohlin, 2003). In addition, children who are prone to high intensity pleasure are likely highly impulsive and active (Rothbart, Ahadi, Hershey, & Fisher, 2001), so they often may behave in inappropriate ways. Moreover, adults and peers likely expect intense and frequent negative emotions to be increasingly modulated with age, so it is possible that intense negative emotions are increasingly destructive to social interactions (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 1993; Eisenberg, Fabes, Murphy, et al., 1994; Mazsk, Eisenberg, & Guthrie, 1999). Thus, it is important to examine the intensity as well as frequency of emotions.

Stability of Positive Emotionality

In regard to rank ordering of individuals, positive emotionality (observed and reported) has been found to be somewhat stable throughout infancy, toddlerhood, and early childhood (Lemery, Goldsmith, Klinnert, & Mrazek, 1999; Durbin et al., 2007; Rothbart & Bates, 2006). It is possible that the differential stability noted at younger ages is less evident in early adolescence because of the numerous changes that occur during adolescence (see Collins & Steinberg, 2006). However, most researchers have examined general positive affect rather than the intensity, and there are few data examining rank-order stability across childhood into adolescence.

There is limited research on the developmental trajectories of children’s positive emotionality. In a review, Rothbart and Bates (2006) reported that positive emotionality (observed and parent-reported) increased in mean level across the first year of life. However, change in the mean level of intense positive affect may vary for children differing in attachment status. Based on paired t tests, Kochanska (2001) found that young children’s joy during several behavioral tasks was stable in mean level in all attachment groups except for the resistant attachment group, whose joy decreased from 9 to 33 months.

During later developmental periods, researchers have found some change as well as some mean-level stability in positive emotionality. For example, Guerin and Gottfried (1994) found that children’s mean level of parent-reported positive mood (intensity and frequency) increased from 3.5 years to 5 years and then remained relatively stable during later elementary school years (8, 10, and 12 years of age). Although adolescents are viewed as emotionally intense (five times more likely to report intense happiness compared to their parents; Larson & Richards, 1994), there tends to be a decline in positive affect (self- and parent-reports) in some contexts in early adolescence (e.g., Collins & Steinberg, 2006; Larson, Richards, Moneta, Holmbeck, & Duckett, 1996). However, there is limited research on changes in the intensity of children’s positive emotionality as they move into adolescence. Our tentative hypothesis was that intensity of children’s positive emotion—which has been related to low regulation (Kochanska et al., 2000)—would decline with age as emotion-related self-regulatory skills emerge and are refined (Rothbart & Bates, 2006).

Stability of Negative Emotionality

Researchers generally have found rank-order stability of negative emotionality between 24 and 48 months (Lemery et al., 1999) and in the elementary school years (Murphy, Eisenberg, Fabes, Shepard, & Guthrie, 1999)—a finding consistent with the considerable heritability of negative emotionality (e.g., Goldsmith et al., 1999). In regard to mean-level changes, although change in negative emotionality varies with attachment status in the first 2 years of life (Kochanska, 2001), Murphy et al. (1999) found a decline in parents’ and teachers’ ratings of children’s negative emotionality (intensity and frequency) from preschool to late elementary school, a finding they attributed to the development of self-regulation. However, relative to childhood, researchers have found increases in the means of intensity and frequency of negative affect (often, but not always, self-reported) in adolescence, especially conflict-related emotion (Larson & Richards, 1994; see Laursen & Collins, 1994) and depressive affect (Garber, Keiley, & Martin, 2002; Hammen & Rudolph, 2003). Thus, given the dual considerations of increasing self-regulatory skills with age in childhood/ adolescence and the increase in negative emotion and conflict in early adolescence, we predicted a decline in emotional intensity across the elementary school years and a possible modest increase in negative emotionality in early adolescence.

Stability of General Emotional Expressivity

Some investigators have examined children’s expressivity, regardless of its valence. Researchers sometimes find that the frequency and intensity of expressivity are positively related, regardless of valence (Bachorowski & Braaten, 1994; Davis & Burns, 1999; Thomas & Diener, 1990). In regard to the stability of expressivity, Aksan et al. (1999) examined the rank-order stability of two types temperaments (reported)—controlled-nonexpressive and noncontrolled-expressive. They found fair to moderate rank-order stability in these designations from age 3.5 to 4.5 years. Eisenberg et al. (2003) also found evidence of differential stability during the elementary school years. Although these findings may partly reflect stability in the familial and cultural context, they also probably are due to the role of heritability in emotionality.

In regard to mean level change, Guerin and Gottfried (1994) found that children’s mean-level general emotional intensity (reported) declined from 3.5 to 5 years and declined again across later elementary school years (see also Eisenberg et al., 2003). Although there are few data on change in mean level of expressivity in childhood, it seemed reasonable to expect a decline in children’s expressivity with age as children learn cultural rules regarding the inhibition of emotion and when expressivity is socially acceptable (Saarni, Campos, Camras, & Witherington, 2006), and as they increasingly develop the ability to inhibit their expressivity (Rothbart & Bates, 2006).

Social Competence and Its Relations to Emotionality

The definition of social competence often depends on the researcher’s theoretical framework, but it generally it involves social skills (e.g., socially appropriate behavior) and social success (e.g., peer likability; Rubin, Bukowski, & Parker, 2006). In this study, we investigated socially appropriate behavior. The beginnings of social skills are seen early in life and children continue developing their skills throughout childhood (Howes, 1987; Rubin et al., 2006). Obradovicć, Van Dulmen, Yates, Carlson, and Egeland (2006) found that reported social competence (e.g., peer relationship quality and social skills) was stable in mean level from early childhood to adolescence (3.5 to 16 years of age). However, they also found that the strength of this stability in structural models declined from early childhood to middle adolescence.

Intuitively, it seems likely that children who display positive emotions during peer interactions reinforce their play partners’ interactions and facilitate future interactions (and the development of socially appropriate behaviors) whereas children who display negative emotions (especially intense emotions) disrupt social interactions and likely engage in fewer interactions over time. Indeed, some researchers have found that displays of positive emotion are positively related to children’s observed and reported social competence (Denham, McKinley, Couchoud, & Holt, 1990; Lengua, 2003; McDowell & Parke, 2005; Sroufe, Schork, Motti, Lawroski, & LaFreniere, 1984). However, Feshbach (1982) found a relation between low social competence (specifically, high levels of aggression) and boys’ relatively intense positive affect in empathy-inducing contexts. As already mentioned, such intense positive affect sometimes may reflect a lack of regulation (Kochanska et al., 2000), which has been negatively related to social competence (see Eisenberg, Vaughan, & Hofer, in press). Moreover, parent-reported child exuberance has been associated with externalizing problems in preschool and elementary school, as well as with low prosocial behavior in preschool (Rydell et al., 2003), and parent-reported high intensity pleasure has been related to externalizing problems in preadolescence (Oldehinkel et al., 2004; see also Kim, Walden, Harris, Karrass, & Caltron, 2007). Thus, it is quite possible that intensity of positive affect is not consistently related to social competence.

Findings are mixed in regard to the relations between negative affect and social competence. For example, Carson and Parke (1996) found that young children who displayed intense negative affect during a parent-child interaction were relatively higher in teacher-rated antisocial behavior (i.e., hitting behavior); however, there were no significant relations between negative affect and teacher-reported peer likability. Denham et al. (2003) found that children’s sad and anger displays generally were unrelated to teacher-rated social competence. In contrast, Eisenberg et al. (1993) found a negative relation between reported negative affect or negative emotional intensity and social competence (e.g., peer acceptance) for preschoolers (for similar findings with adolescents, Dodge, Coie, Pettit, & Price, 1990; Eisenberg et al., 1993; Fabes & Eisenberg, 1992). Additionally, Fabes et al. (1999) found that children who displayed more negative affect during peer interactions also exhibited less socially competent behaviors (e.g., helping others) than children who were not as negatively expressive. Thus, despite some variability in findings, there seems to be a negative relation between negative expressivity and social competence.

Sex Differences in Emotionality and Social Competence

Consistent with the gender stereotype of females’ greater emotionality, researchers have found differences in adults’ perceptions of girls’ and boys’ emotional behavior beginning in elementary school. For example, Fabes and Martin (1991) found that adults perceived girls as more emotionally expressive and intense and increasing in emotionality with age whereas boys’ were viewed as initially increasing in emotionality, leveling off in elementary school, and then decreasing in adolescence. These findings suggest that reported measures of emotion are likely to be influenced by adults’ gender stereotypes (although sometimes parents have not reported gender differences in expressivity; e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2003). Nonetheless, despite any effect of gender stereotypes, adults’ reports of children’s temperamental emotionality appear to be relatively valid indices (Rothbart & Bates, 2006).

Additionally, consistent with the idea that girls may be socialized to express more positive affect as a way to be social (see Brody & Hall, 2000; LaFrance, Hecht, & Paluck, 2003), researchers have sometimes found sex differences in the means. In a recent meta-analysis examining the sex differences in various aspects of temperament, Else-Quest, Hyde, Goldsmith, and Van Hulle (2006) found sex differences in positive emotions (girls were higher in positive mood than boys and boys were higher in high intensity positive affect than girls) but negligible differences in boys’ and girls’ negative affect (see also Murphy et al., 1999).

Sex differences favoring girls in mean levels of reported social competence also have been found (Eisenberg et al., 1995; Mpofu, Thomas, & Chan, 2004). Adult raters likely have biased gender expectations regarding socially competent behavior, and teachers tend to expect boys to display more disruptive behaviors than girls and girls to be more compliant in the classroom (see Parks & Kennedy, 2007). However, girls might actually be more socially appropriate because of their greater self-regulation (Eisenberg et al., 2007; Else-Quest et al., 2006; Kochanska et al., 2000). In addition, in some studies, the relations of social competence to emotionality have differed for boys and girls (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 1993). However, it was unclear if the trajectories of intense emotionality would relate differently to the trajectory of social competence for the two sexes. If emotional expressivity is more acceptable for girls, one might expect a higher positive relation between emotional expressivity and social competence for girls. However, if adults hold stronger expectations regarding appropriate expressivity for girls, then less emotionally competent girls (e.g., those who express intense negative emotions) may be viewed more negatively than their male counterparts.

The Present Study

In the present study, the relations and the trajectories of children’s positive emotional intensity, negative emotional intensity, general expressivity, and social skills were assessed across 6 years. Based on the reviewed research, we predicted that there would be some stability in the rank ordering of these constructs across time, especially because reported measures were used as opposed to specific observed situations (which are more context specific rather than reported dispositional measures; see Durbin et al., 2007). In regard to the mean-level stability, we predicted that children’s negative emotional intensity and overall expressivity would likely exhibit a quadratic trajectory—initially declining as children’s regulation strategies improve and then increasing modestly with movement into adolescence. In contrast, positive affect intensity was tentatively predicted to be stable or decline somewhat through childhood and decline in the later years during early adolescence (Larson et al., 1996). Moreover, socially appropriate behavior was predicted to increase across time as children’s cognitive abilities and awareness of social norms increased and then level off at the older ages.

As children learn social norms and self-presentation strategies (see Saarni et al., 2006), their level of expressivity would be expected to be more situationally appropriate. However, children who experience intense emotions, especially negative ones, may have difficulty modulating their emotional displays in accordance with norms (indeed, adults’ ratings of emotional intensity likely reflect the level of expression of these emotions). We predicted that the trajectories of children’s negative emotional intensity and overall expressivity would negatively predict the trajectories of children’s social skills because relatively intense emotion potentially interferes with the development and execution of socially appropriate behaviors. Although positive emotionality generally has been related with high social competence, this might be less true with intense positive emotions, especially if these emotions reflect lack of regulation (Kochanska et al., 2000). Therefore, we were unsure if intense positive emotion would be related to higher or lower social competence (or unrelated).

In regard to sex differences, given the mixed findings from research with adults’ perceptions (Fabes & Martin, 1991) and with younger children’s emotionality (see Else-Quest et al., 2006), the tentative predictions were that boys would be higher in positive emotional intensity than girls and boys and girls would be similar in their negative emotional intensity (Else-Quest et al., 2006; Murphy et al., 1999). However, girls were expected be higher in general expressivity, even if they were not higher in intensity of emotion. Additionally, we predicted that the relations of emotionality and social skills would be similar for girls and boys.

Method

Participants

Children and their primary caregiving parent were participants in a longitudinal study of emotional and social development. Participants were 199 children (97 girls; M age = 90 months, SD = 14) in kindergarten through third grade at Time (T1), 166 children (84 girls; M age = 112.80 months, SD = 13.79) at Time 2 (T2; 2 years after T1), 167 children (84 girls; M age = 137.33 months, SD = 13.95) at Time 3 (T3; 4 years after T1), and 157 children (79 girls; M age = 160.80 months, SD = 14.4) at Time 4 (T4; 6 years after T1). Primary caregivers were mothers except for a few fathers (ns = 8, 9, 10, and 6, for T1, T2, T3, and T4, respectively).

At T1, a majority of the families reported that they were European American (79%); 10% were Hispanic, 4% were African American, 2% were Native American, fewer than 1% were Asian American, and 5% were of mixed origin. The participants were mostly from middle-class families (mean family income at T1 = $46,000, SD = $24,000; mean years of education = 14.60 and 14.99 for mothers and fathers, respectively, SDs = 2.00 and 2.55). More detail on sample characteristics for each assessment is reported elsewhere (for T1, Eisenberg et al., 1996; for T2, Eisenberg et al., 2000; for T3, Zhou et al., 2002; for T4, Eisenberg et al., 2005).

Attrition Analyses

To examine variables related to attrition between T1 and T4, separate MANOVAs and χ2 analyses (for categorical data) with attrition status as the independent variable were computed for demographic variables as well as the major study variables. There were no significant differences between the T4 participants and those who dropped out after T1.

Procedure

Families were recruited for participation through letters sent home from school. Primary caregivers completed questionnaires regarding their children’s social and emotional behaviors during a laboratory visit, although some (mostly those who moved away) at each time responded by mail. Children’s current teachers also completed questionnaires similar in nature. All participants received a small payment. The general procedure was the same for the initial assessment at T1 and the following assessments each 2 years apart (T2, T3, and T4).

Measures

Positive and Negative Emotional Intensity

At each assessment, parents and teachers rated (1 = never to 7 = always) children’s positive emotional intensity (PEI) and negative emotional intensity (NEI) using an adaptation of Larsen and Diener’s (1987) Affect Intensity Scale (Eisenberg et al., 1995; six items for PEI, e.g., “When my child accomplishes something difficult, s/he feels delighted”; five items for NEI, e.g., “When my child experiences anxiety, it normally is very strong”). Alphas at T1, T2, T3, and T4 for PEI were .79, .84, .83, and .86 for parents, and .90, .92, .88, and .87 for teachers; alphas for NEI = .72, .74, .86, and .79 for parents, and .85, .86, .87, and .86 for teachers.

Overall Expressivity

At T2, T3, and T4, parents and teachers rated (1 = never true to 6 = always true) children’s expressivity using a slightly adapted version (from a self-report to other-report scale; Eisenberg, Losoya, et al., 2001) of Kring, Smith, and Neale’s (1994) 17-item Emotional Expressivity Scale (e.g., “Other people believe this child to be very emotional”; alphas for parents at T2, T3, and T4 = .90, .90, and .92; alphas for teachers = .95, .95, and .95).

Social Competence

At T1, T2, T3, and T4, teachers rated children’s socially appropriate behavior (four items; e.g., “This child is usually well behaved”; alphas = .92, .90, .89, and .68 at T1, T2, T3, and T4, respectively) on a 4-point response scale (i.e., selected an option and indicated if the items was “sort of” or “really” true) using an adapted version of Harter’s (1982) Perceived Competence Scale for Children (see Eisenberg et al., 1995). Teachers were optimal reporters because of their opportunities to children’s social behavior with peers and their exposure to the diversity of social skills among children (which can be used as a basis for judgments).1

Results

Descriptive analyses are presented first. Then the results from the rank-order stability analyses (correlations) and the mean-level stability analyses (latent growth curves, LGC) on the individual variables are presented. Because of the range of ages in the sample, age-based LGC were conducted (see below for more details). Next, the LGCs predicting children’s trajectory (slope) of social competence from their trajectories for PEI, NEI, and expressivity are presented.

Descriptive Statistics

Means and standard deviations of the measures are presented in Table 1. All variables demonstrated acceptable levels of normality (see Curran, West, & Finch, 1996). Family income was unrelated to any of the variables; mothers’ education was negatively related to parent-reported PEI at T2, r(162) = −.17, p = .03, and positively related to social skills at T3, r(150) = .21, p = .01. The correlations when mothers’ education were covaried and not covaried were similar; thus, mothers’ education was not covaried in further analyses.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations

|

Ms (SD) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | |

| Parent-reported positive emotional intensity | 4.92 (.92) | 4.98 (1.01) | 4.75 (.99) | 4.63 (1.06) |

| Girls | 5.10 (.92) | 5.21 (.90) | 4.97 (.80) | 4.86 (.96) |

| Boys | 4.74 (.89) | 4.75 (1.07) | 4.52 (1.11) | 4.40 (1.12) |

| Parent-reported negative emotional intensity | 3.96 (.95) | 4.24 (1.08) | 4.07 (1.16) | 3.91 (1.05) |

| Girls | 3.89 (.93) | 4.31 (1.10) | 4.10 (1.18) | 3.87 (1.08) |

| Boys | 4.01 (.98) | 4.16 (1.07) | 4.03 (1.15) | 3.95 (1.02) |

| Parent-reported expressivity | — | 4.29 (.73) | 4.13 (.76) | 4.06 (.78) |

| Girls | 4.34 (.68) | 4.12 (.69) | 4.20 (.76) | |

| Boys | 4.24 (.78) | 4.15 (.83) | 3.92 (.78) | |

| Teacher-reported positive emotional intensity | 3.99 (1.16) | 4.14 (1.26) | 3.80 (1.27) | 3.67 (1.24) |

| Girls | 3.99 (1.12) | 4.22 (1.26) | 3.81 (1.16) | 3.44 (1.24) |

| Boys | 3.99 (1.21) | 4.07 (1.26) | 3.80 (1.37) | 3.91 (1.21) |

| Teacher-reported negative emotional intensity | 3.53 (1.25) | 3.61 (1.30) | 3.20 (1.28) | 3.07 (1.19) |

| Girls | 3.34 (1.10) | 3.29 (1.15) | 2.98 (1.18) | 2.87 (1.04) |

| Boys | 3.72 (1.35) | 3.91 (1.38) | 3.41 (1.34) | 3.29 (1.30) |

| Teacher-reported expressivity | — | 3.85 (1.02) | 3.66 (1.02) | 3.45 (1.01) |

| Girls | 3.95 (.92) | 3.69 (.94) | 3.35 (1.00) | |

| Boys | 3.75 (1.11) | 3.64 (1.08) | 3.56 (1.01) | |

| Teacher-reported socially appropriate behavior | 3.22 (.82) | 3.27 (.80) | 3.35 (.78) | 3.13 (.50) |

| Girls | 3.55 (.63) | 3.57 (.62) | 3.67 (.53) | 3.28 (.37) |

| Boys | 2.90 (.85) | 2.98 (.84) | 3.04 (.85) | 2.96 (.58) |

Note. Total sample ranged from 144–199. T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2; T3 = Time 3; T4 = Time 4.

For each time point, MANOVAs or ANOVAs with sex as the independent variable were computed for the following dependent variables: (1) parent-reported PEI, NEI, and expressivity, (2) teacher-reported PEI, NEI, and expressivity, and (3) teacher-reported social competence. All multivariate effects for sex were significant except for teacher-reported PEI, NEI, and expressivity at T1 (only marginal) and T3 (not significant). Numerous univariate effects were significant. Girls were viewed by parents as higher in PEI than boys at T1, T2, T3, and T4, Fs(1, 188/160/162/152) = 7.56, 9.53, 8.62, and 7.46, ps = .01 (see means in Table 1), and as higher in expressivity than boys at T4, F(1, 152) = 5.06, p = .03. Boys were viewed by teachers as higher than girls in NEI at T1, T2, T3, and T4, Fs(1, 197/156/142/138) = 4.51, 9.88, 4.04, and 5.61, ps = .04, .01, .05, and .02, and PEI at T4, F(1, 138) = 6.84, p = .01, and as lower in social skills at T1, T2, T3, and T4, Fs(1, 197/156/146/145) = 37.62, 25.00, 8.57, and 18.01, ps = .01.

Rank-Order Stability

The rank order of the major variables across time was examined with correlations. Differences in the correlations for boys and girls were tested using the Fisher r-to-z transformation formula (Steiger, 1980).

For PEI, NEI, and expressivity, the relations across time and across reporter were computed. Overall, there were numerous significant, positive relations across time within reporter, especially for parents’ reports (likely because teachers were different at each assessment; see Table 2). Thus, there was considerable evidence of differential stability. Additionally, there was some evidence for across-reporter relations, albeit less than for within-reporter (teacher or parent) relations. There were no sex differences in the relations.

Table 2.

Relations of PEI, NEI, and Expressivity

| P1 PEI | T1 PEI | P2 PEI | T2 PEI | P3 PEI | T3 PEI | P4 PEI | T4 PEI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 PEI | — | |||||||

| T1 PEI | .22** | — | ||||||

| P2 PEI | .62** | .21** | — | |||||

| T2 PEI | .24** | .43** | .30** | — | ||||

| P3 PEI | .57** | .11 | .69** | .25** | — | |||

| T3 PEI | .07 | .40** | .15*** | .37** | .15*** | — | ||

| P4 PEI | .49** | .19* | .67** | .24** | .71** | .20* | — | |

| T4 PEI | .12 | .39** | .09 | .33** | .09 | .22* | .14*** | — |

| P1 NEI | T1 NEI | P2 NEI | T2 NEI | P3 NEI | T3 NEI | P4 NEI | T4 NEI | |

| P1 NEI | — | |||||||

| T1 NEI | .17* | — | ||||||

| P2 NEI | .46** | .24** | — | |||||

| T2 NEI | .01 | .33** | .16*** | — | ||||

| P3 NEI | .45** | .15*** | .66** | .18* | — | |||

| T3 NEI | .09 | .33** | .20* | .39** | .15*** | — | ||

| P4 NEI | .40** | .16* | .60** | .22* | .65** | .19* | — | |

| T4 NEI | .12 | .22** | .15*** | .36** | .04 | .41** | .24** | — |

| P2 EXP | T2 EXP | P3 EXP | T3 EXP | P4 EXP | T4 EXP | |||

| P2 EXP | — | |||||||

| T2 EXP | .34** | — | ||||||

| P3 EXP | .63** | .31** | — | |||||

| T3 EXP | .08 | .37** | .28** | — | ||||

| P4 EXP | .54** | .17* | .56** | .15*** | — | |||

| T4 EXP | .13 | .30** | .14 | .33** | .05 | — | ||

Note. Degrees of freedom ranged from 128–161 for parents’ reports and 116–158 for teachers’ reports. p = parent; T = teacher; PEI = positive emotional intensity; NEI = negative emotional intensity; EXP = expressivity.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .10.

There was evidence that individuals maintain their rank ordering in social competence. All six correlations across time for teachers’ ratings were significant, rs(123–158) = .38–.70, ps < .01, and there were no sex differences in the relations.

Relations of Emotion With Social Competence

There were a number of significant correlations between social competence and PEI, NEI, or expressivity. More specifically, there were negative correlations between PEI and social skills, especially for boys (see Table 3). In regard to NEI, there were numerous negative correlations with social skills, especially for teachers’ reports (see Table 3). For expressivity, there were negative correlations with socially appropriate behavior (see Table 3). Many of the significant correlations between social competence and emotion-related constructs were for teachers’ reports; however, there also were some significant relations with parents’ reports of emotion. There were relatively few correlations between the emotion-related measures and social competence that differed significantly for boys and girls (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Relations of Emotion-Related Constructs With Socially Appropriate Behavior

| T1 SAB | T2 SAB | T3 SAB | T4 SAB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 PEI | −.09 | −.07 | −.01 | −.06 |

| T1 PEI | −.22** | −.24** | −.13 | −.06 |

| P2 PEI | −.11 | −.08 | −.14 | −.04 |

| T2 PEI | −.11 | −.14*** | −.18* | −.06 |

| P3 PEI | .03 | −.04 | .02 | −.08 |

| T3 PEI | −.10 | −.02 | −.10 | .11a |

| P4 PEI | −.05 | −.11 | −.08 | −.06 |

| T4 PEI | −.19* | −.20* | −.21* | −.21* |

| P1 NEI | −.15* | −.01 | −.05 | .07 |

| T1 NEI | −.57** | −.36** | −.30** | −.13 |

| P2 NEI | −.12 | −.20* | −.13 | −.12 |

| T2 NEI | −.45** | −.59** | −.49** | −.27** |

| P3 NEI | −.10 | −.23** | −.22**,b | −.08 |

| T3 NEI | −.43** | −.43** | −.55** | −.21* |

| P4 NEI | −.15*** | −.28** | −.21* | −.21* |

| T4 NEI | −.33** | −.47** | −.36** | −.39** |

| P2 EXP | −.05 | −.17* | −.18* | −.17*** |

| T2 EXP | −.11 | −.11 | −.15*** | −.07 |

| P3 EXP | −.10 | −.10 | −.06 | −.12 |

| T3 EXP | −.11 | −.03 | −.12 | .13 |

| P4 EXP | −.05 | −.15*** | −.11 | −.16*** |

| T4 EXP | −.12 | −.23** | −.16*** | −.18* |

Note. Degrees of freedom in parentheses. p = parent; T = teacher; PEI = positive emotional intensity; NEI = negative emotional intensity; EXP = expressivity; SAB = socially appropriate behavior.

The relation is greater for boys, r(59) = .26, p < .05, than girls, r(62) = −.20, ns, z = 2.56, p < .05.

The relation is more negative for boys, r(73) = −.38, p < .01, than girls, r(72) = −.02, ns, z = 2.27, p < .05.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .10.

Mean-Level Stability

Muthén and Muthén’s (1998–2007) Mplus 4.2 was used to compute the LGC analyses; the full information maximum likelihood estimation procedure was used under the assumption that missing values are missing at random. For all age-based LGCs, a model with the intercept and linear slope was first estimated. Next, for all age-based LGCs involving variables measured at four time points, a model with the intercept, linear slope, and quadratic slope was estimated, using individually varying age as the metric for the growth curves. The metrics for each assessment were centered on the mean age of children. More specifically, the age-based LGCs use age t scores for the growth metric as opposed to the traditional models that use the number of the assessment (i.e., 0, 1, 2, 3). Many common fit statistics are not defined for individually varying age-based models because factor loadings are random effects, requiring numerical integration for parameter estimation (Muthén & Muthén’s, 1998–2007). Therefore, the linear and quadratic models were compared using the Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC); a smaller BIC indicates a better fit.

Because most fit indices are not calculated for the age-based models, models also were computed using time of assessment rather than age. These models produce various fit indices. In the traditional LGC (i.e., the assessment-based models that provide the typical fit indices), if the model did not fit, the quadratic slope was added to the model if the measure was assessed at all four time points (see Bollen & Curran, 2006). If there was a psi matrix error suggesting overfactoring (i.e., negative error variance because of the quadratic term not being well identified for the model), a segmented or piecewise model was specified (i.e., model freeing one of the time point estimates; see Bollen & Curran, 2006). The cut-points for fit indices recommended by Hu and Bentler (1999) were used. Mehta and West (2000) indicated that a model using individually varying age produces more accurate parameter estimators for the sample instead of an assessment-based model. Unstandardized estimates are reported and labeled as β.

The intercept is the status or rating of a particular variable for the average age of children at T1 for age-based models or the mean average at T1 (regardless of age) for the traditional models. In all analyses, these were significantly different from 0 (which is not surprising given the scales of the measures; e.g., 1 to 4); thus, the significance of the intercepts is not discussed further. The slope indicated the average trajectory for children across time. Significant variance in the intercept or slope indicated whether children differed in their initial status or slope.

Trajectories of Emotional Intensity

LGC analyses were estimated separately for parents’ and teachers’ reports of PEI and NEI across T1, T2, T3, and T4. Both age-based and traditional LGC analyses were conducted.

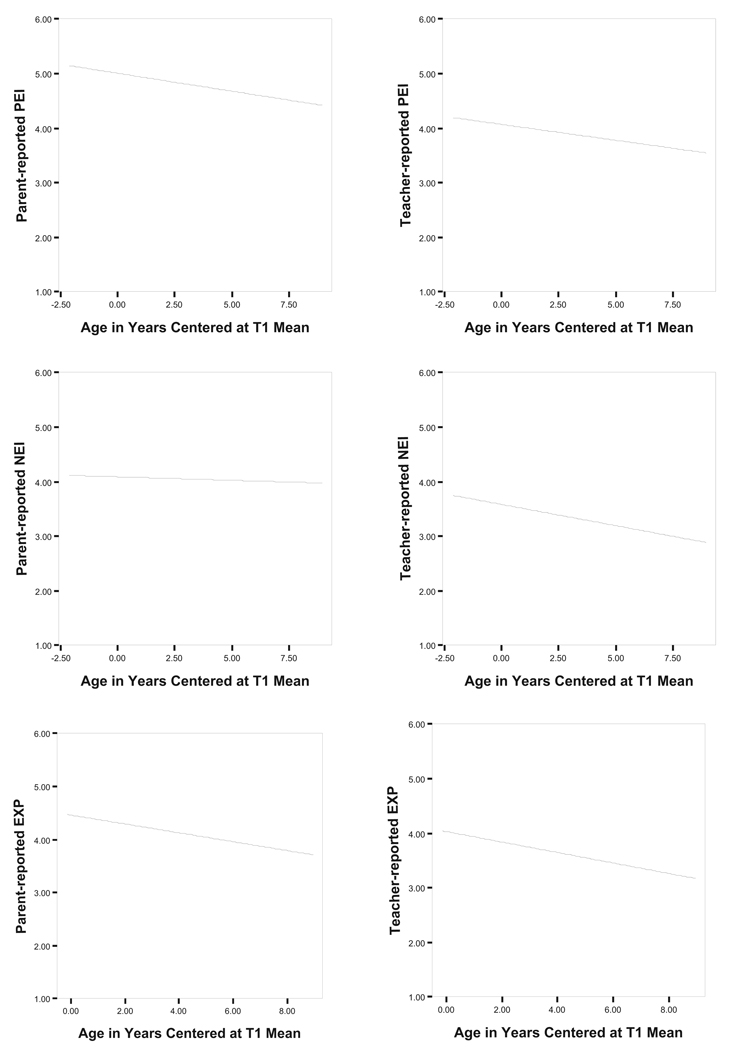

Parent-reported PEI

Based on a linear, individually varying age-based LGC estimating the means and variances for the intercept and linear slope, children’s estimated linear (negative) trajectory was significant, β = −0.06, p < .01 (see Figure 1). Additionally, there was variability for children’s initial mean, β = 0.47, p < .01, but no significant variance in the estimated slope, β = 0.01. The quadratic model produced a psi matrix error, suggesting overfactoring; thus, the linear model was used in further analyses, BIC = 1409.81.

Figure 1.

The average trajectory of emotion constructs.

The assessment-based LGC fit the data: χ2(5) = 13.50, p = .02; CFI = 0.97; RMSEA = 0.09 (confidence interval 90%; CI = 0.03, 0.15); SRMR = 0.04; BIC = 1660.12. The estimated linear slope (negative) was significant (β = −0.11, p < .01). There was variability in the intercept (mean level at average age at T1; β = 0.56, p < .01) and in the linear slope, β = 0.04, p < .05.

Teacher-reported PEI

Based on a linear, individually varying age-based LGC estimating the means and variances for the intercept and linear slope, children’s (negative) trajectory was significant, β = −0.06, p < .01 (see Figure 1). Additionally, there was variability for the initial mean, β = 0.58, p < .01. When the variance of the linear slope was estimated, the model did not converge properly because of lack of variability in the slope; thus, the slope variance was fixed at 0. The quadratic model produced a psi matrix error, suggesting overfactoring; therefore, only the linear model was interpreted, BIC = 1851.17. Overall, teacher-rated PEI followed a similar declining trajectory, as parent-rated PEI, despite an initial modest increase from T1 to T2.

A similar approach to the traditional LGC that was used for parent-rated PEI was used for teacher-rated PEI. The final model included latent constructs of the intercept and linear slope with the variance of the linear slope fixed to 0 (in the initial model, the variance of the slope was −0.03, ns): χ2(6) = 9.36, ns; CFI = .96; RMSEA = 0.05 (CI = 0.00, 0.12); SRMR = 0.06. The estimated linear slope was significant, β = −0.11, p < .05. There was significant variability in the intercept (mean level of PEI at T1; β = 0.68, p < .01).

Parent-reported NEI

Based on a linear, individually varying, age-based LGC, the slope and variance for the slope were nonsignificant, βs = −0.01 and 0.01, ns (see Figure 1). There was variability in the intercept, β = 0.42, p < .01. Overall, NEI remained stable across time, BIC = 1600.77. The quadratic model produced a psi matrix error, suggesting overfactoring.

The traditional LGC that included latent constructs of the intercept and linear slope did not fit the data well; thus, a quadratic term was added. However, this model produced a psi matrix error; thus, the fourth time point for the slope was freed (see Bollen & Curran, 2006). This piecewise (or segmented) LGC fit: χ2(4) = 19.01, p < .01; CFI = .93; RMSEA = 0.14 (CI = 0.08, 0.20); SRMR = 0.06; BIC = 1,846.82. The mean and variance of the slope were not significant. There was variability in the intercept, β = 0.37, p < .01.

Teacher-reported NEI

Based on a linear, individually varying, age-based LGC, the estimated mean trajectory (negative) was significant, β = −0.08, p < .01 (see Figure 1), and there was variability in the intercept, β = 0.52, p < .01. When the variance of the linear slope was estimated, the model did not converge properly because of lack of variability in the slope; thus, the slope variance was fixed at 0. The quadratic model produced a psi matrix error, suggesting overfactoring. Overall, teacher-rated NEI followed a declining linear trajectory, BIC = 1,822.19.

The final traditional LGC model included latent constructs of the intercept and linear slope: χ2(5) = 9.92, ns; CFI = .94; RMSEA = 0.07 (CI = 0.00, 0.13); SRMR = 0.07; BIC = 2,113.03. The estimated negative linear slope was significant, β = −0.17, p < .01. There was variability in the intercept, β = 0.65, p < .01, but not in the linear slope.

Trajectories of Expressivity

Parent-reported expressivity

In the linear, individually varying, age-based model, children’s estimated linear trajectory (negative) was significant, β = −0.06, p < .01 (see Figure 1). There was variability for the initial mean, β = 0.32, p < .05, but there was not significant variance for the slope. Overall, parent-rated expressivity declined with age, BIC = 902.12.

The final traditional LGC model included latent constructs of the intercept and linear slope, χ2(1) = 1.17, ns; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = 0.03 (CI = 0.00, 0.20); SRMR = 0.02; BIC = 1,012.45. The estimated negative linear slope was significant, β = −0.10, p < .01. There was variability in the intercept, β = 0.38, p < .01, but not in the linear slope.

Teacher-reported expressivity

In the individually varying age-based model, children’s estimated mean linear trajectory (negative) was significant, β = −0.09, p < .01 (see Figure 1). There also was near significant variance for the intercept, β = 0.54, p < .10, but not for the slope. Similar to parents’ reports, teacher-rated expressivity declined across time, BIC = 1,161.91.

The final traditional LGC included latent constructs of the intercept and linear slope: χ2(1) = 0.13, ns; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = 0.00 (CI = 0.00, 0.14); SRMR = 0.01; BIC = 1,293.39. The estimated negative linear slope was significant, β = −0.19, p < .01. There was variability in the intercept, β = 0.44, p < .01, but not in the linear slope.

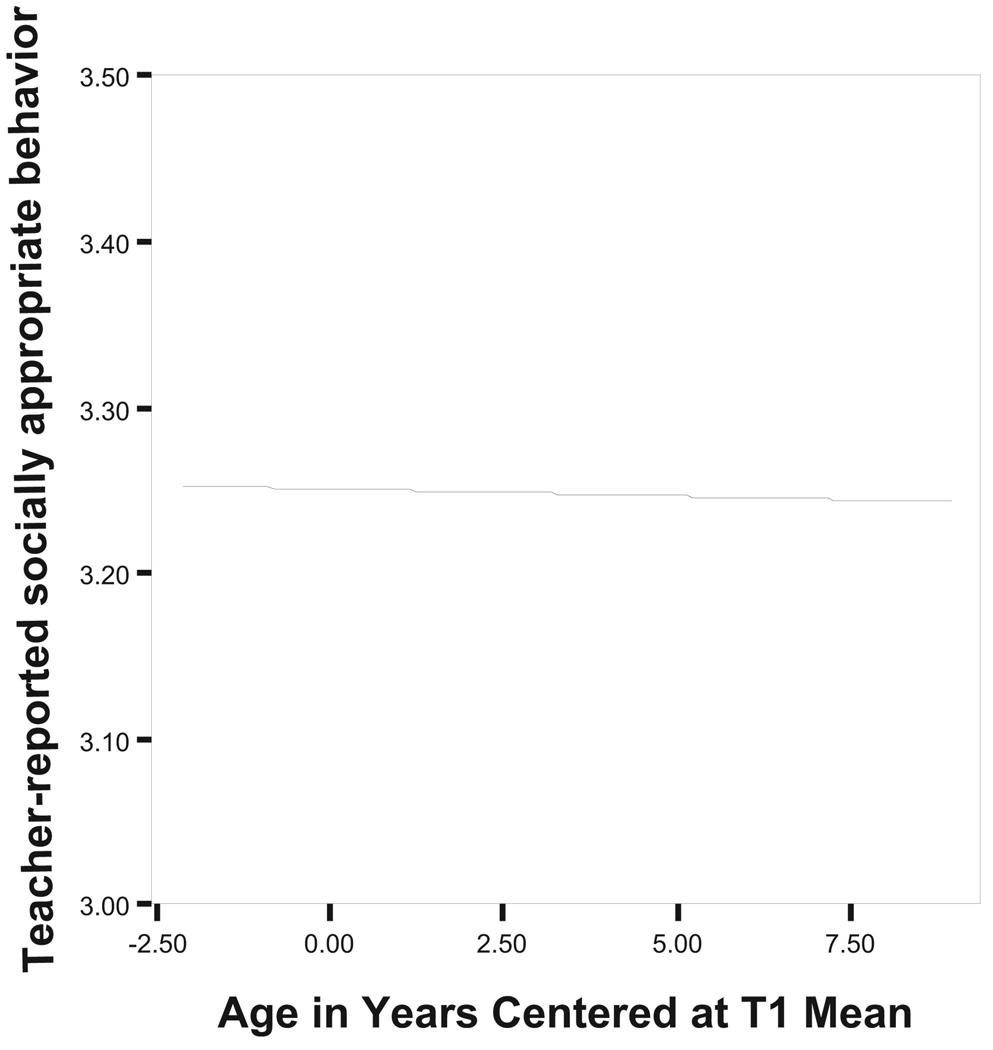

Trajectory of Teacher-Reported Socially Appropriate Behavior

Based on a linear, individually varying, age-based LGC means and variances estimated for the intercept and linear slope, the variance of the intercept and the mean trajectory (negative) were significant, βs = 0.32 and −0.03, ps < .01 (see Figure 2). The model did not converge when the variance of the slope was estimated; therefore, the slope variance was fixed at 0. The quadratic model did not converge. Thus, based on the final linear model, BIC = 1,126.22, there was an overall decline in socially appropriate behavior, albeit very modest in magnitude.

Figure 2.

The average trajectory of socially appropriate behavior.

The traditional LGC that included latent constructs of the intercept and linear slope did not fit the data well; thus, a quadratic term was added. However, this model produced a psi matrix error, suggesting overfactoring. Therefore, a piecewise approach was taken to fitting the model. The best model included the intercept and slope factors with the time estimates at T3 and T4 released and the variance of the slope factor fixed at 0. This LGC fit adequately: χ2(4) = 9.66, p = .05; CFI = .98; RMSEA = 0.08 (CI = 0.01, 0.15); SRMR = 0.07; BIC = 1232.44. The estimated slope and variance for the intercept were significant, βs = −0.04 and 0.38, ps < .01.

Sex Differences

For each of the above models, a multiple-groups model was estimated to examine differences in the means in intercepts and slopes for girls and boys. In an initial model for each construct, the means for intercept and slope (linear and/or quadratic) factors were set to 0 for girls (boys were estimated relative to girls) to test if there was a sex difference in the parameters. Because the factor means for girls were set to 0, a negative estimated value for either the intercept or slope indicated that boys were lower than girls and a positive estimate indicated the reverse. Of the seven models that were estimated, three models had significant differences in the intercept and one model had a significant difference in the slope. The intercept for girls was higher for parent-rated PEI, higher for teacher-rated social skills, and lower for teacher-rated NEI, βs = −0.38, −0.65, and 0.46, ps < .01 (see Table 1 for means). In the model with teacher-rated expressivity, the slope was significantly different for girls and boys, β = 0.20, p < .05. A second multiple-groups model (without the constraint of setting the factors for the girls to 0) was estimated so that the value of the slope could be computed for girls and boys. The slope for girls was significant, β = −0.29, p < .01, whereas the slope for boys was not significant, β = −0.09, ns.

Summary of Single Variable LGC

Overall, all of the LGC (individually varying aged-based and traditional) involving the emotion variables and socially appropriate behavior had significant declining trajectories, with the exception of the stable trajectory of parent-rated NEI. All of the LGC models had significant variability in the intercepts but not in the slope factors, except for teacher-rated expressivity, which had marginally significant variability in the intercept.

Growth Curve to Growth Curve Prediction

For each final age-based LGC model of parents’ and teachers’ ratings of PEI, NEI, and expressivity, structural (i.e., predictive) paths were added from the intercept and linear slope of these constructs to the latent constructs of teacher-rated socially appropriate behavior. Thus, six models were estimated in which a construct of emotion predicted social competence. Alternative models with structural paths of social competence predicting emotion also were estimated.

PEI and Socially Appropriate Behavior

The LGC model with parent-reported PEI predicting socially appropriate behavior did not have any significant predictive paths. The model with teacher-reported PEI had two significant paths— the initial status (T1 intercept) of teacher-reported PEI negatively predicted the intercept of socially appropriate behavior and positively predicted the slope of socially appropriate behavior, βs = −0.39 and 0.04, ps < .01 and .05. In other words, children who started higher at the initial mean age of T1 in PEI were rated lower in social skills at T1. Additionally, because of the positive prediction of the social skills, children who started higher in PEI at T1 had a steeper decline (i.e., higher rate of change) in socially appropriate behavior across time.

NEI and Socially Appropriate Behavior

The initial status of NEI in the LGC models of both parents’ and teachers’ ratings significantly predicted the initial status of children’s socially appropriate behavior, βs = −0.30 and −0.83, ps < .05 and .01. Thus, children who started higher in NEI were lower in social skills. Additionally for the teacher-reported NEI model, the initial status on NEI positively predicted children’s trajectory of social skills, β = 0.07, p < .01. In other words, children who started higher in NEI at T1 had a steeper decline in social skills across time.

Expressivity and Socially Appropriate Behavior

There were no significant predictive paths with the model involving mother-reported expressivity. The model with teachers’ ratings of expressivity had one significant path and one marginal path. The initial status of teacher-rated expressivity negatively predicted children’s initial status of socially appropriate behavior and positively predicted children’s trajectory of socially appropriate behavior, βs = −0.39 and 0.04, ps < .05 and .10. Thus, children who started higher in expressivity at T1 had a marginally steeper decline in social skills across time.

Socially Appropriate Behavior Predicting Emotion

Out of the six models estimated for social skills predicting PEI, NEI, and expressivity, only one model had a significant path predicting the slope of emotion. The intercept of socially appropriate behavior negatively predicted the trajectory of mother-rated expressivity, β = −6.14, p < .01. Children who started higher in social skills had a more gradual decline (i.e., lower rate of change) in mother-rated expressivity. Children who started lower in social skills had higher intercepts in three models: (1) teacher-rated PEI, β = −0.45, p < .05; (2) teacher-rated NEI, β = −1.19, p < .01; and (3) mother-rated expressivity, β = −0.19, p < .10. These findings with the intercepts are consistent with the growth-to-growth analyses of emotion predicting social skills.

Summary of Growth-to-Growth Analyses

In general, the analyses with PEI, NEI, and expressivity predicting social competence had similar results—higher emotion at T1 predicted a steeper decline in socially appropriate behavior across time, although these findings were only for teachers’ reports. Additionally, for PEI, NEI (parent- and teacher-rated), and expressivity, higher emotion at T1 predicted lower social skills at T1. When social competence was specified as predicting emotion, children who started higher in social skills had a more gradual decline in mother-rated expressivity.

Discussion

In the present study, the rank-order and mean-level stability of PEI, NEI, expressivity, and socially appropriate behavior and the relations of children’s emotion-related constructs with socially appropriate behavior were assessed. We found evidence of rank-order stability and mean-level change in all constructs.

Regarding rank-order stability, there was some evidence of agreement between reporters within time and considerable evidence of stability across time in teachers’ or parents’ ratings of the constructs. Based on the relations, it appears that parents perceived more stability than teachers, which is not surprising given the changing classroom environment and different teachers at each assessment. There also were some significant, positive correlations between parents’ and teachers’ ratings of the same index of emotionality across time. This stability in individual differences was to be expected for aspects of emotion that reflect temperament/personality. The stability of individual differences in social competence also was not surprising, especially because social behaviors were reported within similar contexts (i.e., classroom environments). It is interesting that the relations among teachers’ ratings of social competence were moderate (rs = .38 to .70) whereas some of the relations among emotion constructs for teachers’ ratings were more modest (although still significant; rs = .22 to .43).

Of most interest in terms of longitudinal prediction were the relations between trajectories for children’s intensity of emotion and their social competence as reported by teachers. Overall, children who began higher in all emotion-related constructs (i.e., PEI, NEI, and expressivity) had a steeper decline in social skills, especially for teacher-rated emotion. Additionally, there was evidence that children who began higher in the emotion-related constructs also started lower in social skills. In contrast, there was only one instance of significant prediction of the emotion-related constructs from social skills (i.e., prediction of mother-rated expressivity from social skills). Children who were initially more socially skilled declined less with age in their expressivity. Perhaps socially skilled children express affect more appropriately and/or at a more modulated level and, thus, have less need to change their levels of expressivity with age. The fact that an initially high level of social skills predicted lower teacher-rated PEI and NEI and lower mother-rated expressivity is consistent with this speculation.

The fact that similar predictive relations between emotionality and social competence were not found for parent-reported PEI and NEI suggests that the relation of social competence to PEI and to NEI may be confined to the school setting and interactions with peers in public versus home environments. It is likely that expressions of emotion, especially very intense emotion, have more relevance for social behavior when expressed at school, where such emotions are especially likely to be deemed as disruptive to the learning environment and as violations of normative expectations. It is also possible that teachers are more honest or unbiased reporters than are parents of children’s problematic emotionality, although recall that there was modest agreement in the rank ordering of emotion constructs between parents and teachers.

Thus, although the findings do not prove causality, they are consistent with the view that children’s emotionality affects their socially appropriate behavior. The findings also are consistent with the generally negative correlations between adult-reported PEI, NEI, and expressivity and teachers’ reports of social skills, within and often across time. Children who experience intense negative emotions are likely to have difficulty modulating their attention and behavior in ways that are socially appropriate (e.g., Aksan et al., 1999; Eisenberg et al., 1993), and the negative interactions that occur may result in further declines in social competence.

Another issue examined was change in mean levels of the variables with age or assessment. In regard to the single variable, age-based LGC models, parents’ and teachers’ ratings followed similar declining trajectories, except for parent-reported NEI, which was stable. These trajectories did not have significant variance—meaning children had similar trajectories. Specifically, based on teachers’ and parents’ ratings of affect, children followed similar negative trajectories; this lack of variability may account for the absence of the prediction of socially appropriate behavior from the trajectories of the emotion variables. The observed declines provided evidence that children’s emotions not only became less intense (positive and negative), but also were exhibited to a lesser degree with age. Other researchers have found declines in negative emotional intensity (e.g., Murphy et al., 1999) and declines in positive affect during childhood and early adolescence (Collins & Steinberg, 2006; Larson et al., 1996; Weinstein, Mermelstein, Hankin, Hedeker, & Flay, 2007). Even though in early adolescence, intensity of emotions has been found to be higher than in childhood (Larson & Richards, 1994; Laursen & Collins, 1994), some researchers have found a decline in affect (i.e., positive and negative affect along a continuous scale) from late childhood to early adolescence when affect was measured outside of the parent-child context (Larson, Moneta, Richards, & Wilson, 2002). Consistent with Larson et al. (2002), our findings suggest that the pattern of increasing affect is not present in early adolescence or at least not present in situations other than parent-child interactions.

The declines in emotional intensity and in expressivity might be because of children’s developing regulation skills. In addition, some researchers have attributed declines in emotional expressiveness to socializers’ pressure to regulate emotions, especially sadness (Fuchs & Thelen, 1988). As children grow older, they are better able to control and verbally communicate their emotional experiences (Saarni et al., 2006). Both socialization processes and development of regulation likely work in concert and interact with each other to foster adaptive development.

Another possible explanation for why children’s emotional intensity and expressivity declined across the 6-year period is children’s changing peer group. Some children experience a heightened awareness of peer-evaluation and peer-group influence (O’Brien & Bierman, 1988), which in turn may create an increase in self-evaluation and a desire to blend into the group as much as possible. Thus, being average or low in intensity and expressivity might be desirable.

For socially appropriate behavior, we predicted that children’s socially appropriate behavior would follow an increasing linear trajectory; however, the overall trajectory was negative, albeit very modest. By T4, nearly all of the children were transitioned into middle school. As these transitions occur, children are forced to quickly adapt to their surroundings and their coping and social skills may be stressed and challenged (Isakson & Jarvis, 1999). Another change is in the growing importance of the peer group (Furman & Buhrmester, 1992), perhaps partly because time spent with peers compared to adults is longer than at younger ages (see Spear, 2000). Adolescents exhibit much higher rates of risk-taking behavior than other age-groups (see Spear, 2000; Dahl, 2004) and this, as well as deviant behavior, might be reinforced by peers. Such behavior is likely to be viewed as socially inappropriate by teachers.

Overall, there was little evidence of sex differences in differential or mean stability of emotion or social functioning. However, teacher-rated expressivity declined for girls but not boys. There also was evidence of sex differences in the means at specific assessments. Girls were rated higher in social competence by teachers (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 1995; Mpofu et al., 2004). Additionally, unlike the findings of Else-Quest et al. (2006) based mostly on younger children, girls were rated higher in PEI by parents but not teachers and lower in NEI by teachers but not parents. Girls may more freely express positive emotion in the home where it is likely to be more acceptable, but modulate it more at school. Similarly, girls may be more likely than boys to modulate their intense negative emotions in the school setting. In the future, it would be interesting to examine teachers’ and parents’ values pertaining to emotions and personal definitions of socially appropriate behavior. Adults’ bases of judgments likely differ, as might the aspects of behavior that capture their attention in the classroom versus home context. For example, teachers may focus more on intense negative emotions or have different expectations for socially appropriate behavior than parents. In fact, teachers’ ratings of children’s NEI have been found to be more related to observed anger than parents’ ratings (Eisenberg, Fabes, Nyman, Bernzweig, & Pineulas, 1994).

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study include the investigation of both rank-order and mean-level stability across a 6-year period and the use of individually varying age-based LGC analyses to assess relations of emotionality with social competence. Multiple reporters for emotional intensity (parents and teachers) and social competence (different teachers at each assessment) were used. In the future, it would be interesting to investigate the trajectories of children’s emotions and behaviors as they transition from early adolescence through late adolescence and to obtain observed measures and youths’ own perceptions of their behaviors. Because of the presence of heightened self-criticism and evaluation during adolescence (Shahar, Henrich, Blatt, Ryan, & Little, 2003), examining the contributions of self-perceived emotional and social behavior could provide a unique perspective. Additionally, it would be interesting to investigate the trajectories of differentiated emotions as opposed to the broader families of emotion.

In conclusion, this study provides unique insight into the developmental trends of emotional behaviors as well as the relations between emotion and socially appropriate behavior. The most interesting findings that emerged were the predictions of social behavior from emotional behavior—children who started higher in emotional behavior had steeper declines in socially appropriate behavior than children who started lower in emotional behavior. The sensitivity to the age of the sample contributes to a greater understanding of children’s emotional and social behavior from early elementary school to early adolescence.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation and National Institute of Mental Health awarded to Nancy Eisenberg.

Footnotes

Teachers’ also rated children’s popularity on the same 4-point response scale used to assess socially appropriate behavior (e.g., “This child has a lot of friends”; alphas = .95, .93, .92, and .88 at T1, T2, T3, and T4, respectively; see Eisenberg et al., 1995). Popularity was stable across assessment points, rs(123–158) ranged from .32 to .47, ps < .01. Popularity was negatively related to teacher-reported (12 of 16 correlations [rs = −.19 to −.48]) and parent-reported NEI (2 of 16 significant for the total sample [rs = −.21 and −.22], one significant for girls [with the sex difference being significant, z = 2.02, p < .05]). Popularity was also positively related to teacher-rated expressivity in 4 of 16 correlations (significant rs ranged from .19 to .39, three correlations were within reporter and time) and teacher-rated PEI (6 of 16 correlations significant [rs ranged from .14 to .39]); findings for parent-reported PEI were not above chance level. All LCG models fit well; popularity did not change in mean level over time or in variability in the slope (which was nonsignificant) and popularity was not predicted by PEI or NEI or expressivity or vice versa.

Contributor Information

Julie Vaughan Sallquist, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University.

Nancy Eisenberg, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University.

Tracy L. Spinrad, School of Social and Family Dynamics, Arizona State University

Mark Reiser, School of Social and Family Dynamics, Arizona State University.

Claire Hofer, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University.

Jeffrey Liew, Department of Educational Psychology, Texas A&M University.

Qing Zhou, Department of Psychology, University of California at Berkeley.

Natalie Eggum, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University.

References

- Aksan N, Goldsmith HH, Smider NA, Essex MJ, Clark R, Hyde JS, et al. Derivation and prediction of temperamental types among preschoolers. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:958–971. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.4.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachorowski J, Braaten EB. Emotional intensity: Measurement and theoretical implications. Personality and Individual Differences. 1994;17:191–199. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Hsieh K, Crnic K. Infant positive and negative emotionality: One dimension or two? Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:289–298. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA, Curran PJ. Latent curve models: A structural equation perspective. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brody LR, Hall JA. Gender, emotion, and expression. In: M L, Haviland-Jones JM, editors. Handbook of emotions. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2000. pp. 338–349. [Google Scholar]

- Carson JL, Parke RD. Reciprocal negative affect in parent-child interactions and children’s peer competency. Child Development. 1996;67:2217–2226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Steinberg L. Adolescence. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of Child Psychology. Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development. 6th ed. New York: Wiley; 2006. pp. 1003–1067. (Series Ed.) (Vol. Ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, West SG, Finch JF. The robustness of test statistics to non-normality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl RE. Adolescent brain development: A period of vulnerabilities and opportunities. Annals of the New York Academy of Science. 2004;1021:1–22. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damasio AR. Emotions and feelings: A neurobiological perspective. In: Manstead AS, Frijda N, Fischer A, editors. Feelings and emotions: The Amsterdam Symposium. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2004. pp. 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Davis PA, Burns GL. Influence of emotional intensity and frequency of positive and negative events on depression. European Journal of Psychological Assessment. 1999;15:106–116. [Google Scholar]

- De Fruyt F, Bartels M, Van Leeuwen KG, De Clercq B, Decuyper M, Mervielde I. Five types of personality continuity in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91:538–552. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.3.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham S, McKinley M, Couchoud EA, Holt R. Emotional and behavioral predictors of preschool peer ratings. Child Development. 1990;61:1145–1152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, Blair KA, DeMulder E, Levitas J, Sawyer K, Auerbach-Major A, et al. Preschool emotional competence: Pathway to social competence? Child Development. 2003;74:238–256. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Larsen RJ. The experience of emotional well-being. In: Lewis M, Haviland JM, editors. Handbook of emotions. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 405–416. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Larsen RJ, Levine S, Emmons RA. Intensity and frequency: Dimensions underlying positive and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1985;48:1253–1265. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.48.5.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Coie JD, Pettit GS, Price JM. Peer status and aggression in boys’ groups: Developmental and contextual analyses. Child Development. 1990;61:1289–1309. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbin CM, Hayden EP, Klein DN, Olino TM. Stability of laboratory-assessed temperamental emotionality traits from ages 3 to 7. Emotion. 2007;7:388–399. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.2.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Bernzweig J, Karbon M, Poulin R, Hanish L. The relations of emotionality and regulation to preschoolers’ social skills and sociometric status. Child Development. 1993;64:1418–1438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Guthrie IK, Murphy BC, Maszk P, Holmgren R, et al. The relations of regulation and emotionality to problem behavior in elementary school children. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:141–162. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Murphy B, Karbon M, Maszk P, Smith M, et al. The relations of emotionality and regulation to dispositional and situational empathy-related responding. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;66:776–797. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.66.4.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Murphy B, Maszk P, Smith M, Karbon M. The role of emotionality and regulation in children’s social functioning: A longitudinal study. Child Development. 1995;66:1360–1384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Nyman M, Bernzweig J, Pinuelas A. The relations of emotionality and regulation to children’s anger-related reactions. Child Development. 1994;65:109–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Guthrie IK, Fabes RA, Shepard S, Losoya S, Murphy BC, et al. Prediction of elementary school children’s externalizing problem behaviors from attentional and behavioral regulation and negative emotionality. Child Development. 2000;71:1367–1382. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Liew J, Pidada SU. The relations of parental emotional expressivity with quality of Indonesian children’s social functioning. Emotion. 2001;1:116–136. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.1.2.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Losoya S, Fabes RA, Guthrie IK, Reiser M, Murphy BC, et al. Parental socialization of children’s dysregulated expression of emotion and externalizing problems. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:183–205. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Michalik N, Spinrad TL, Hofer C, Kupfer A, Valiente C, et al. The relations of effortful control and impulsivity to children’s sympathy: A longitudinal study. Cognitive Development. 2007;22:544–567. doi: 10.1016/j.cogdev.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Vaughan J, Hofer C. Temperament, self-regulation, and peer social competence. In: Rubin K, Bukowski W, Laursen B, editors. Handbook of Peer Interactions, Relationships, and Groups. New York: Guilford Press; (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Zhou Q, Losoya S, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Murphy BC, et al. The relations of parenting, effortful control, and ego control to children’s unregulated expression of emotion. Child Development. 2003;74:875–895. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Zhou Q, Spinrad TL, Valiente C, Fabes RA, Liew J. Relations among positive parenting, children’s effortful control, and externalizing problems: A three-wave longitudinal study. Child Development. 2005;76:1055–1071. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00897.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Else-Quest NM, Hyde J, Goldsmith HH, Van Hulle CA. Gender differences in temperament: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:33–72. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emde RN, Plomin R, Robinson J, Corley R, DeFries J, Fulker DW, et al. Temperament, emotion, and cognition at fourteen months: The MacArthur Longitudinal Twin Study. Child Development. 1992;63:1437–1455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Eisenberg N. Young children’s coping with interpersonal anger. Child Development. 1992;63:116–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Eisenberg N, Jones S, Smith M, Guthrie I, Poulin R, et al. Regulation, emotionality, and preschoolers’ socially competent peer interactions. Child Development. 1999;70:432–442. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Martin CL. Gender and age stereotypes of emotionality. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1991;17:532–540. [Google Scholar]

- Feshbach ND. Sex differences in empathy and social behavior in children. In: Eisenberg N, editor. The development of prosocial behavior. New York: Academic Press; 1982. pp. 315–337. [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Calkins SD. The development of self-control of emotion: Intrinsic and extrinsic influences. Motivation and emotion. 2003;27:7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Roberts RW. Patterns of continuity: A dynamic model for conceptualizing the stability of individual differences in psychological constructs across the life course. Psychological Review. 2005;112:60–74. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.112.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs D, Thelen MH. Children’s expected interpersonal consequences of communicating their affective state and reported likelihood of expression. Child Development. 1988;59:1314–1322. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1988.tb01500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks of personal relationships. Child Development. 1992;63:103–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb03599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber J, Keiley MK, Martin NC. Developmental trajectories of adolescents’ depressive symptoms: Predictors of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:79–95. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH, Lemery KS, Buss KA, Campos JJ. Genetic analyses of focal aspects of infant temperament. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:972–985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. Perspectives on anxiety and impulsivity: A commentary. Journal of Research in Personality. 1987;21:493–509. [Google Scholar]

- Guerin DW, Gottfried AW. Developmental stability and change in parent reports of temperament: A ten-year longitudinal investigation from infancy through preadolescence. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1994;40:334–355. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Rudolph KD. Childhood mood disorders. In: Mash EJ, Barkley RA, editors. Child psychopathology. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 233–278. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon-Jones E. Clarifying the emotive functions of asymmetrical frontal cortical activity. Psychophysiology. 2003;40:838–848. doi: 10.1111/1469-8986.00121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The perceived competence scale for children. Child Development. 1982;53:87–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden EP, Klein DN, Durbin CE, Olino TM. Positive emotionality at age 3 predicts cognitive styles in 7-year-old children. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:409–423. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes C. Social competence with peers in young children: Developmental sequences. Developmental Review. 1987;7:252–272. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Isakson K, Jarvis P. The adjustment of adolescents during the transition into high school: A short term longitudinal study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1999;28:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kim G, Walden T, Harris V, Karrass J, Catron T. Positive emotion, negative emotion, and emotion control in the externalizing problems of school-aged children. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2007;37:221–239. doi: 10.1007/s10578-006-0031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanksa G, Knaack A. Effortful control as a personality characteristic of young children: Antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Personality. 2003;71:1087–1112. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.7106008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G. Emotional development in children with different attachment histories: The first three years. Child Development. 2001;72:474–490. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Coy KC, Tjebkes TL, Husarek SJ. Individual differences in emotionality in infancy. Child Development. 1998;64:375–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Murray KT, Harlan ET. Effortful control in early childhood: Continuity and change, antecedents, and implications for social development. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:220–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kring AM, Smith DA, Neale JM. Individual differences in dispositional expressiveness: Development and validation of the Emotional Expressivity Scale. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;66:934–949. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.66.5.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFrance M, Hecht MA, Paluck EL. The contingent smile: A meta-analysis of sex differences in smiling. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:305–344. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen RJ, Diener E. Affect intensity as an individual difference characteristic: A review. Journal of Research in Personality. 1987;21:1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, Richards MH. Divergent realities: The emotional lives of mothers, fathers, and adolescents. New York: Basic Books; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW, Moneta G, Richards MH, Wilson S. Continuity, stability, and change in daily emotional experience across adolescence. Child Development. 2002;73:1151–1165. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW, Richards MH, Moneta G, Holmbeck G, Duckett E. Changes in adolescents’ daily interactions with their families from ages 10 to 18: Disengagement and transformation. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:744–754. [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, Collins WA. Interpersonal conflict during adolescence. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:197–209. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemery KS, Goldsmith HH, Klinnert MD, Mrazek DA. Developmental models of infant and childhood temperament. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:189–204. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ. Associations among emotionality, self-regulation, adjustment problems, and positive adjustment in middle childhood. Applied Developmental Psychology. 2003;24:595–618. [Google Scholar]

- Maszk P, Eisenberg N, Guthrie IK. Relations of children’s social status to their emotionality and regulation: A short-term longitudinal study. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1999;45:468–492. [Google Scholar]

- McDowell DJ, Parke RD. Parental control and affect as predictors of children’s display rule use and social competence with peers. Social Development. 2005;14:440–457. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta PD, West SG. Putting the individual back into individual growth curves. Psychological Methods. 2000;5:23–43. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.5.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mpofu E, Thomas KR, Chan F. Social competence in Zimbabwean multicultural schools: Effects of ethnic and gender differences. International Journal of Psychology. 2004;39:169–178. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy BC, Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Shepard S, Guthrie IK. Consistency and change in children’s emotionality and regulation: A longitudinal study. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1999;45:413–444. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus Software and User’s Guide. 4th ed. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2007. [Google Scholar]

- Obradović J, Van Dulmen MH, Yates TM, Carlson EA, Egeland B. Developmental assessment of competence from early childhood to middle adolescence. Journal of Adolescence. 2006;29:857–889. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldehinkel AJ, Hartman CA, de Winter AF, Veensstra R, Ormel J. Temperament profiles associated with internalizing and externalizing problems in preadolescence. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:421–440. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]