Abstract

Background and Purpose

The importance of bioactive lipid signaling under physiologic and pathophysiologic conditions is progressively becoming recognized. The disparate distribution of sphingosine kinase (SphK) isoform activity in normal and ischemic brain, particularly the large excess of SphK2 in cerebral microvascular endothelial cells, suggests potentially unique cell- and region-specific signaling by its product sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P). The present study sought to test the isoform-specific role of SphK as a trigger of hypoxic preconditioning (HPC)-induced ischemic tolerance.

Methods

Temporal changes in microvascular SphK activity and expression were measured following HPC. The SphK inhibitor dimethylsphingosine (DMS) or sphingosine analog FTY720 was administered to adult male Swiss-Webster ND4 mice prior to HPC. Two days later, mice underwent a 60-min transient middle cerebral artery occlusion and, at 24 h of reperfusion, infarct volume, neurological deficit, and hemispheric edema were measured.

Results

HPC rapidly increased microvascular SphK2 protein expression (1.7±0.2 fold) and activity (2.5±0.6 fold) peaking at 2h, while SphK1 was unchanged. SphK inhibition during HPC abrogated reductions in infarct volume, neurological deficit, and ipsilateral edema in HPC-treated mice. FTY720 given 48 h prior to stroke also promoted ischemic tolerance; when combined with HPC, even greater (and DMS-reversible) protection was noted.

Conclusions

These findings indicate hypoxia-sensitive increases in SphK2 activity may serve as a proximal trigger that ultimately leads to S1P-mediated alterations in gene expression that promote the ischemia-tolerant phenotype. Thus, components of this bioactive lipid signaling pathway may be suitable therapeutic targets for protecting the neurovascular unit in stroke.

Keywords: bioactive lipids, neuroprotection, endothelium, neurovascular unit, focal stroke

Cerebral ischemic tolerance is the resistance of cerebral tissue to ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury that is transiently induced following a preconditioning stimulus. I/R injury can be characterized by many interconnected pathologies, including inflammation, loss of vascular barrier integrity, reactive oxygen species production, and apoptosis.1 The ischemia-tolerant brain is protected against these injurious mechanisms via numerous adaptive responses triggered by preconditioning stimuli2-4, such as hypoxia; hence, in vivo preconditioning models can be used to identify endogenous factors responsible for these protective effects2-6. Although the mechanisms underlying preconditioning and ischemic tolerance are recognized as potential therapeutic targets for the treatment of stroke2,3,5,6, the induction and expression phases of cerebral ischemic tolerance still require considerable elucidation. Targeting the induction phase may be particularly advantageous to stimulate multiple protective pathways with a single trigger.

Given the lack of successful stroke treatments resulting from neuronally-oriented protection efforts, an expanded focus on the role of vascular mechanisms and the protection of the neurovascular unit following stroke has been advocated7-10. Sphingosine kinase (SphK) and its product sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) are vascular, particularly endothelial cell, mediators that regulate calcium mobility, migration, proliferation, survival, angiogenesis, and permeability11-13. S1P also activates signaling molecules implicated in the induction of cerebral ischemic tolerance, such as Akt and eNOS14-16, suggesting a potential role for S1P signaling as an early inducer of the gene expression changes promoted by preconditioning. While delayed preconditioning in isolated mouse heart depends on SphK1 activation17, divergent amino acid sequences, substrate specificities, and expression patterns of the two main SphK isoforms indicate unique, tissue-specific roles for each18. While SphK1 has greater expression and activity than SphK2 in many tissues, in the brain—and particularly in cerebral microvascular endothelial cells—SphK2 expression levels are greater than SphK119,20, pointing to more prominent physiologic roles for SphK2 in brain and brain vasculature.

Therefore, we sought to ascertain the dependence of HPC-induced cerebral ischemic protection on microvascular SphK activity in an adult mouse model of transient focal stroke. To test this hypothesis, we assessed temporal protein expression and activity patterns for each SphK isoform in microvascular isolates early after HPC, during the induction phase of preconditioning. A causal role for SphK signaling in establishing an ischemia-tolerant phenotype was studied by inhibiting SphK activity during HPC, and determining the ability of a SphK2-specific sphingosine analogue to mimic HPC. Our results indicate a role for microvascular SphK2 signaling inducing cerebral ischemic tolerance, thereby providing a definitive therapeutic target for neurovascular unit protection in stroke.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Two hundred twenty-four adult male Swiss-Webster ND4 mice (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) were used in this study as follows: 45 for SphK protein expression, 68 for SphK activity analyses, 8 for verification of in vivo SphK2 inhibition with DMS, and 103 for in vivo ischemia experiments, as detailed in Table 1. Animals were housed on a 12-hour light/dark cycle with water and food ad libitum. Efforts were made to reduce the number of mice used and minimize stress to the animals. All experimental procedures were approved by the Washington University Animal Studies Committee.

Table 1.

Inclusion-Exclusion Criteria for Ischemia Experiments

| Experimental Group |

Included Mice |

Excluded Mice |

Total Mice |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Died During Surgery |

Incomplete Blockage |

Early Reperfusion |

No Reperfusion |

Hemorrhage | |||

| Sham HPC |

7 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 10 |

| HPC | 10 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 19 |

| DMS HPC |

5 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| DMS | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 11 |

| Low FTY720 |

7 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 15 |

| High FTY720 |

5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| FTY720 HPC |

9 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 21 |

| DMS FTY720 HPC |

5 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 12 |

In Vivo Hypoxic Preconditioning (HPC)

Mice were preconditioned with 4 h systemic hypoxia as described previously4 by transferring them to new cages continually flushed with 8% oxygen (balance nitrogen). Control mice underwent sham preconditioning (sham HPC) by transferring the mice to a new cage flushed with normoxic air for 4 h. HPC preceded transient ischemia by 48 h.

Pharmacological Treatments

The nonselective sphingosine kinase inhibitor dimethylsphingosine (DMS, 0.33 mg/kg, i.v.)21 was administered by retroorbital injection alone or immediately prior to the injection of the SphK2-specific substrate, FTY720 (0.24 or 1.0 mg/kg, i.p.)22, 30 min prior to HPC. For mice not subjected to HPC, pharmacological treatment preceded transient ischemia by 48 h.

Transient Focal Cerebral Ischemia

A 60-min transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO) was induced in mice anesthetized with halothane as previously described23. Blood flow through the MCA was measured by laser Doppler flowmetry. Mice retaining greater than 15% of baseline perfusion during ischemia and mice that did not reach at least 50% of baseline by 5 min post-reperfusion or 70% after 24 h were excluded. In addition, animals showing evidence of intracerebral bleeding or subarachnoid hemorrhage upon brain extraction were excluded from the study. The exclusion criteria used to eliminate mice from further consideration are tabulated in Table 1. Experimental conditions were intermixed to prevent batch effects from affecting a single experimental condition.

Infarct and Edema Quantification

Infarct volume was delineated 24 h after tMCAO with 2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining using an intensity threshold in Sigma Scan Pro 4. Total infarct volume was corrected for edema4. Edema was quantified as the increase in ipsilateral hemispheric volume relative to the contralateral hemisphere.

Neurological Deficit Scoring

Neurological deficit was scored 24 h after reperfusion, immediately prior to sacrifice, as described previously4.

Microvessel Isolation

Cortical samples collected at 0, 1, 2, 4, and 24 h after HPC were snap frozen and microvessel-rich homogenates were prepared as described previously24 with a few modifications: 5% phosphatase inhibitor buffer (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) was added to the sucrose buffer; the initial 1000g spin was not repeated; and the final 200g spin was 2 min. The microvessel-enriched pellet was washed with 0.01 mol/L PBS, spun 2 min at 8000g, the supernatant discarded, and the pellet frozen at −80 °C.

Immunoblotting

Microvessel-rich homogenates were sonicated in lysis buffer (Cell Lysis Buffer [Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA], Pefabloc [Roche, Indianapolis, IN], Pefabloc Plus [Roche], EDTA-free protease inhibitor solution [Roche], and phosphatase inhibitor [Active Motif]), and sphingosine kinase 1 and 2 protein expression was detected using commercially available antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

Sphingosine Kinase Activity Assay

Microvessel-rich homogenates were sonicated in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 10 mmol/L KCl, 20% glycerol, 2 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 15 mmol/L NaF, 2 mmol/L semicarbazide, and EDTA-free complete protease inhibitor (Roche)). Lysates were cleared at 15,000 × g for 10 min and SphK activity was measured with an established assay using NBD-sphingosine (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL)25. SphK activity was measured in 50 mmol/L Hepes, pH 7.4, 15 mmol/L MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 10 mmol/L ATP, 15 mmol/L NaF, and 2 mmol/L semicarbazide, and 10 μmol/L NBD-sphingosine substrate, with either 0.5% Triton X-100 added for SphK1 specificity or 1 mol/L KCl added for SphK2 specificity. Reactions were started by adding microvascular lysate. The 50-μl reactions were extracted as described25. NBD fluorescence was read using 100 μl of upper aqueous phase, combined with 50 μl of dimethylformamide. Reactions containing no enzyme were used for blanks.

Statistical Analyses

Comparisons were done with SigmaStat software, using ANOVA and the Holm-Sidak method, with p<0.05 accepted as significant.

Results

Physiological Measurements

Physiological characteristics of the experimental mice are shown in Table 2. There were no differences in age, body weight, or middle cerebral artery blood flow during ischemia or during early or late reperfusion among experimental groups.

Table 2.

Physiological Variables (Mean±SEM) of Mice Subjected to Transient Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion

| Experimental Group |

Age (wks) |

Body Mass (g) |

Ischemic CBF (%) |

5 min Reperfusion CBF (%) |

24 h Reperfusion CBF (%) |

Infarct Volume (mm3) |

Neurological Deficit (0-4) |

Ipsilateral Edema (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham HPC |

13±2 | 31±2 | 8±1 | 89±3 | 86±6 | 70±6 | 1.8±0.1 | 6.5±0.7 |

| HPC | 11±2 | 32±1 | 9±2 | 89±4 | 97±5 | 29±4 | 1.0±0.2 | 1.9±0.6 |

| DMS HPC |

14±1 | 30±1 | 7±1 | 95±10 | 99±10 | 70±14 | 1.8±0.1 | 3.4±0.8 |

| DMS | 16±1 | 33±1 | 8±1 | 77±7 | 93±7 | 61±11 | 1.6±0.2 | 5.2±1.0 |

| Low FTY720 |

15± 2 | 32±1 | 8±2 | 82±6 | 101±7 | 57±8 | 1.4±0.1 | 3.8±0.5 |

| High FTY720 |

11±0 | 31±1 | 8±1 | 77±9 | 90±7 | 38±8 | 0.9±0.2 | 1.5±0.4 |

| FTY720 HPC |

14±1 | 31±1 | 8±1 | 94±8 | 103±7 | 13±4 | 0.9±0.2 | 0.9±0.7 |

| DMS FTY720 HPC |

13±1 | 31±1 | 8±3 | 89±7 | 86±5 | 62±5 | 2.0±0.2 | 3.9±0.8 |

HPC Upregulates SphK2, but Not SphK1, Protein Expression and Activity

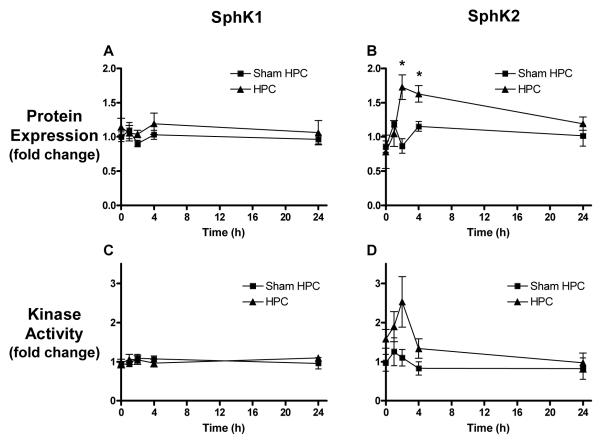

SphK1 and SphK2 protein expression in microvessels in vivo was measured at various times over the first 24 h following HPC. No change in microvascular SphK1 was revealed (Figure 1A), while SphK2 increased after HPC, exhibiting a 1.7±0.2 fold increase peaking at 2 h (Figure 1B). Because protein expression does not necessarily reflect the activity of the enzymes, isoform-specific SphK activity was measured. As with protein expression, microvascular SphK1 activity was unchanged following HPC (Figure 1C), but SphK2 activity changes after HPC showed the same trend seen with SphK2 protein expression, albeit with a slightly higher increase in peak activity (2.5±0.6 fold over sham HPC) than protein expression (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Sphingosine kinase (SphK) 1 and SphK2 protein expression and activity following either hypoxic preconditioning (HPC) or sham HPC. (A) SphK1 protein expression showed no change following HPC or sham HPC treatment. (B) SphK2 expression was elevated by HPC, peaking 2 h following HPC. For A and B, N=4, normalized to β-actin and then sham HPC. (C) Activity of SphK1 showed no change following HPC or sham HPC. (D) Activity of SphK2 increased, trending similar to SphK2 protein expression, peaking 2 h after HPC. For C and D, N=4-5 for sham HPC and N=6-8 for HPC, normalized to β-actin and then sham HPC. Data represent mean ± SEM. *P<0.05 vs. the HPC group at 0 h and sham HPC at the same timepoint.

HPC-Induced Ischemic Protection Depends on SphK

To test if the increase in SphK2 protein expression and activity is vital to HPC-induced ischemic protection, we used our adult mouse model of transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO)4 and inhibited the activity of SphK during HPC with DMS. First, we confirmed that DMS given intravenously would inhibit the increase in SphK2 activity seen following HPC (shown in Figure 1D). DMS given 30 min prior to HPC reduced peak SphK2 activity 2 h after HPC by approximately 50% (n=4, data not shown).

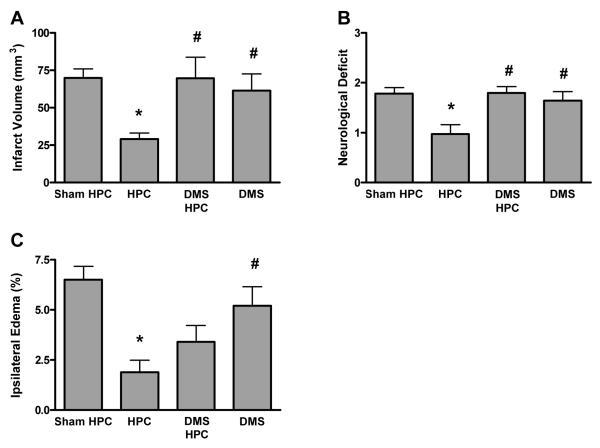

We then documented that DMS prior to HPC completely abolished (P<0.05) the reduction in infarct volume provided by this preconditioning stimulus (Figure 2A). Improvements in neurological deficit scores (45% reduction relative to sham HPC) obtained with HPC (Figure 2B) were also fully blocked (P<0.05) by SphK inhibition during HPC, consistent with the hypothesis that HPC-induced protection requires SphK activity. Finally, the significant reduction in postischemic ipsilateral edema by HPC (71% reduction, Figure 2C) was partially lost when SphK was inhibited during HPC by DMS (48% reduction).

Figure 2.

(A) The significant reduction in cerebral infarct volume in animals receiving hypoxic preconditioning (HPC) 48 hours prior to transient middle cerebral artery occlusion is abolished by the administration of the sphingosine kinase inhibitor dimethylsphingosine (DMS) prior to HPC. Infarct volumes were corrected for edema. (B) DMS prior to HPC blocks the reduction in postischemic neurological deficit induced by HPC. (C) DMS prior to HPC blocks the reduction in postischemic ipsilateral edema induced by HPC. Data represent mean ± SEM. N-values shown in Table 1. P<0.05 vs. (*) sham PC; (#) DMS/HPC.

FTY720 Mimics Preconditioning, Provides Synergistic Protection with HPC

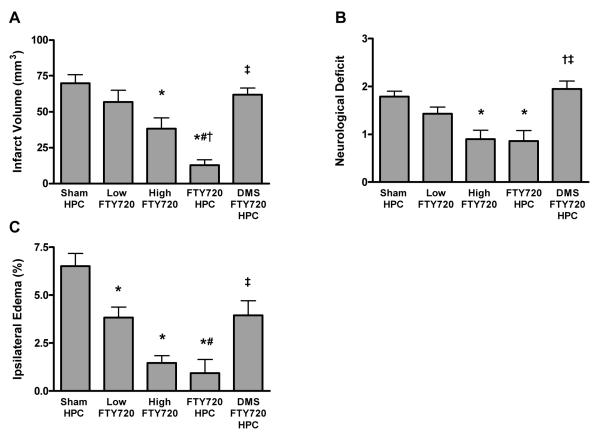

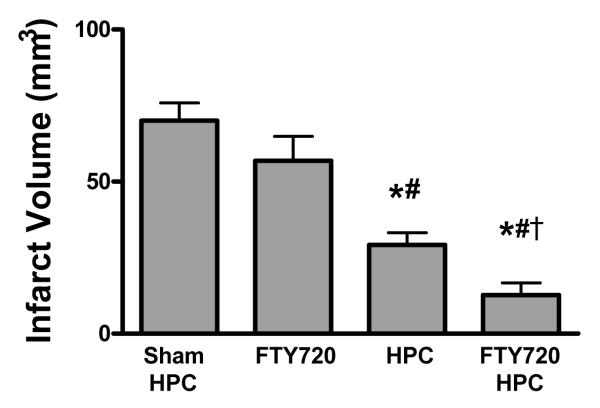

As a pharmacologic mimic for HPC-induced SphK activation, we administered the SphK2 substrate and sphingosine analog FTY720—which, when activated by SphK2-mediated phosphorylation, then serves as an S1P analogue—48 h prior to ischemia in the absence of HPC. FTY720 provided dose-dependent protection across all three endpoints when used as a preconditioning mimic (Figure 3). When the low dose of FTY720 was administered concomitant with HPC, robust, synergistic tolerance was evidenced. DMS blocked (P<0.05) this protection, consistent with our contention that an HPC-induced increase in SphK2 activity mediates the induction of ischemia-protective effects. Similarly, postischemic neurological deficits and ipsilateral edema were also reduced (P<0.05) by a combination of FTY720 and HPC, and both these effects were blocked (P<0.05) by SphK inhibition with DMS (Figure 3B and 3C). The combination of the low dose of FTY720 and HPC provided a protection greater than HPC alone (Figure 4), indicating that FTY720 potentiates the SphK2-mediated protection induced by HPC.

Figure 3.

(A) A low dose of FTY720 (0.24 mg/kg) given 48 h prior to stroke was not protective, but a high dose (1 mg/kg) did mimic the protection provided by HPC. Administration of the low dose of FTY720 combined with HPC provided a robust protection against infarction caused by transient middle cerebral artery occlusion. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM edema-corrected infarct volume. (B) High dose FTY720, or low dose combined with HPC, reduces neurological deficit. (C) High dose FTY720, or low dose combined with HPC, reduces postischemic ipsilateral edema. N-values shown in Table 1. P<0.05 vs. (*) sham PC; (#) Low FTY720; (†) High FTY720; (‡) FTY720/HPC.

Figure 4.

A low dose of FTY720 (0.24 mg/kg) combined with HPC provided significantly greater protection against infarct volume than HPC alone, indicative of a synergistic effect wherein HPC provides enough activation of SphK2 to phosphorylate exogenous FTY720. N-values shown in Table 1. P<0.05 vs. (*) sham PC; (#) Low FTY720; (†) HPC.

Discussion

We have shown that the expression and activity level of the SphK2 isoform in the cerebral microvasculature is increased following HPC, while SphK1 is unchanged. Inhibiting SphK during HPC with DMS blocks the typical reduction in infarct volume and neurological deficit, and partially blocks the reduction in ipsilateral edema, afforded by preconditioning. Administering the SphK2-specific sphingosine analog FTY720 in the absence of HPC provided dose-dependent protection, but even a low dose of FTY720, when given concomitant with HPC, provided greater protection than HPC alone. These findings indicate that HPC-induced ischemic tolerance is mediated by an increase in microvascular SphK2 activity, and thereby identify a novel endogenous pathway of ischemic protection that could be targeted for the treatment of stroke.

The lack of success of neuroprotective agents in clinical trials10, has led to a call for an increased focus on vascular mechanisms for improving stroke outcome7,9,10. The present study examined the role of cerebral microvascular SphK signaling in the induction of ischemic tolerance following HPC. Unique, multi-factorial damage to the cerebral microvasculature occurs early and progressively worsens after stroke, leading to loss of blood-brain barrier (BBB) integrity8,10 and ipsilateral edema that can exacerbate ischemia/reperfusion damage8,10 and increase the probability of hemorrhagic transformation26. Inflammation at the vascular wall, with increased leukocyte adhesion and neutrophil infiltration9,10, also occurs. Heterogeneity of the vascular endothelium27 suggests that mechanisms mediating both injury and protection in brain endothelium may differ from those in other tissues.

Several studies have measured indices of cerebrovascular protection induced by preconditioning. LPS preconditioning abrogated the ischemia-induced impairment of endothelium relaxation in arterioles28, possibly via increased eNOS expression15, thereby contributing to the preservation of microvascular perfusion following ischemia29. Preconditioning was also documented to reduce postischemic ipsilateral edema30. Our observation that inhibiting SphK activity during preconditioning reversed the reduction in edema normally afforded by HPC, and the ability of the SphK2 substrate FTY720 to reduce postischemic edema when given as a preconditioning mimic, implicates SphK—most likely the SphK2 isoform—as playing a vasculoprotective as well as neuroprotective role.

Although the mechanisms by which HPC induces ischemic tolerance are not well understood, the prominent role of SphK2 signaling in microvascular endothelium early after HPC suggests a number of S1P-mediated possibilities. S1P may protect the vasculature by reducing leukocyte adhesion secondary to altering endothelial adhesion molecule expression22 and preventing endothelial apoptosis via Bcl2 activation31. There is also evidence that S1P may act as a proximal trigger of cerebroprotection (both neuronal and vascular) via activation of signaling molecules such as Akt and eNOS14-16. Our data also demonstrates a SphK2 signaling dependent decrease in ipsilateral edema resultant from HPC prior to ischemic insult. While S1P has not been directly implicated in BBB maintenance, it can decrease endothelial permeability32 via multiple mechanisms, including regulating pericyte interactions33 and adherens junction formation12,34. S1P was also shown to enhance endothelial barrier integrity by stimulating ZO-1/α-catenin interactions at cellular junctions35. The wealth of previous work showing that S1P signaling improves vascular barrier integrity suggests preservation of the blood brain barrier, mediated by S1P-driven transcriptional or posttranslational modifications, may be a primary mechanism contributing to preconditioning-induced ischemic tolerance. Further studies of the mechanistic basis of S1P-mediated ischemic protection in brain, particularly at the level of the BBB, are needed to document these vascular-based protective effects.

Our expression and activity analyses suggest that it is the SphK2 isoform that is involved in mediating HPC-induced ischemic tolerance, in contrast to the findings in other organs, such as heart, where ischemic protection is mediated by SphK1 signaling17. The increase in SphK2 protein expression and activity we observed following hypoxia fits with previous studies in brain that showed, unlike in other tissues, only SphK2 mRNA increased following ischemia, while SphK1 mRNA remained unaffected20. Hypoxia is also documented to increase SphK2 activity in other cells as well36. At higher doses, the SphK2 substrate FTY720 served as a preconditioning mimic, while at a lower dose, FTY720 concomitant with HPC exhibited a synergistic effect, promoting robust ischemic tolerance as a result of HPC-induced SphK2 activity and the subsequent increased phosphorylation of the exogenously-supplied substrate. Given that FTY720 is already in clinical trials for the treatment of multiple sclerosis37, this drug by itself, or in conjunction with SphK2 stimulation, could be used to protect against stroke. The high-magnitude protection achieved in our study when FTY720 was administered concomitant with HPC—greater than afforded by HPC alone for infarction volume—and the fact that FTY720 is phosphorylated exclusively by the SphK2 isoform19,38, also supports our conclusion that increased SphK2 activity/expression following HPC is responsible for inducing an ischemia-tolerant phenotype in brain.

Despite these findings, the abrogation of HPC-induced tolerance with the nonspecific inhibitor DMS does not allow us to completely rule out the participation of SphK1, and the lack of an isoform-specific inhibitor precluded such an experiment. Studies in SphK1 and SphK2 knockout mice would confirm with more certainty an isoform-specific role for SphK2 in cerebral ischemic tolerance. While SphK protein expression and activity were measured specifically in the microvasculature, our results also cannot rule out a role for SphK2 signaling from nonmicrovascular cell types, since SphK inhibition via intravenous delivery of DMS presumably inhibits SphK activity in multiple cell types. Evidence of SphK2 stimulation in neurons and astrocytes following ischemia20, suggests a cooperative or synergistic signaling among the various cell types may also occur in response to HPC. In fact, Blondeau, et al. showed SphK2 upregulation 24 h after brief ischemia in cultured neurons and astrocytes, but not in endothelial cells20, which, together with our data, may suggest the possibility of a temporally-based paracrine effect, where endothelial cells provide an early increase in SphK2 activity that ultimately leads to a later activation of the same enzyme in neurons and astrocytes.

Summary

In summary, our findings indicate that, unlike in myocardium, an increase in SphK2 expression and activity following HPC participates in establishing the reductions in infarct size and edema associated with ischemic tolerance. These findings point to a new signaling pathway for the treatment of stroke. Elucidation of the SphK2-associated signal transduction pathways that ultimately promote the ischemia-tolerant phenotype could collectively serve as therapeutic targets for neurovascular unit protection in the stroke patient.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Angie Freie for assistance with microvessel isolation and immunoblotting.

Source of Funding This work was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute RO1 HL79278-03 (to J.M.G.) and the Spastic Paralysis Research Foundation of the Illinois-Eastern Iowa District of Kiwanis International (T.S.P.).

Footnotes

Disclosures None

References

- 1.Lo EH, Dalkara T, Moskowitz MA. Mechanisms, challenges and opportunities in stroke. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:399–415. doi: 10.1038/nrn1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Obrenovitch TP. Molecular physiology of preconditioning-induced brain tolerance to ischemia. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:211–247. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00039.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gidday JM. Cerebral preconditioning and ischaemic tolerance. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:437–448. doi: 10.1038/nrn1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller BA, Perez RS, Shah AR, Gonzales ER, Park TS, Gidday JM. Cerebral protection by hypoxic preconditioning in a murine model of focal ischemia-reperfusion. Neuroreport. 2001;12:1663–1669. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200106130-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barone FC. Endogenous brain protection: Models, gene expression, and mechanisms. Methods Mol Med. 2005;104:105–184. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-836-6:105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yenari M, Kitagawa K, Lyden P, Perez-Pinzon M. Metabolic downregulation: A key to successful neuroprotection? Stroke. 2008;39:2910–2917. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.514471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faraci FM. Vascular protection. Stroke. 2003;34:327–329. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000054052.52510.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodriguez-Yanez M, Castellanos M, Blanco M, Mosquera E, Castillo J. Vascular protection in brain ischemia. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2006;21(Suppl 2):21–29. doi: 10.1159/000091700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Endres M, Engelhardt B, Koistinaho J, Lindvall O, Meairs S, Mohr JP, Planas A, Rothwell N, Schwaninger M, Schwab ME, Vivien D, Wieloch T, Dirnagl U. Improving outcome after stroke: Overcoming the translational roadblock. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;25:268–278. doi: 10.1159/000118039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fagan SC, Hess DC, Hohnadel EJ, Pollock DM, Ergul A. Targets for vascular protection after acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2004;35:2220–2225. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000138023.60272.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bryan L, Kordula T, Spiegel S, Milstien S. Regulation and functions of sphingosine kinases in the brain. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1781:459–466. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kluk MJ, Hla T. Signaling of sphingosine-1-phosphate via the s1p/edg-family of g-protein-coupled receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1582:72–80. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00139-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saba JD, Hla T. Point-counterpoint of sphingosine 1-phosphate metabolism. Circ Res. 2004;94:724–734. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000122383.60368.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y, Park TS, Gidday JM. Hypoxic preconditioning protects human brain endothelium from ischemic apoptosis by akt-dependent survivin activation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H2573–2581. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01098.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Puisieux F, Deplanque D, Pu Q, Souil E, Bastide M, Bordet R. Differential role of nitric oxide pathway and heat shock protein in preconditioning and lipopolysaccharide-induced brain ischemic tolerance. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;389:71–78. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00893-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morales-Ruiz M, Lee MJ, Zollner S, Gratton JP, Scotland R, Shiojima I, Walsh K, Hla T, Sessa WC. Sphingosine 1-phosphate activates akt, nitric oxide production, and chemotaxis through a gi protein/phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:19672–19677. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009993200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin ZQ, Zhang J, Huang Y, Hoover HE, Vessey DA, Karliner JS. A sphingosine kinase 1 mutation sensitizes the myocardium to ischemia/reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;76:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu H, Sugiura M, Nava VE, Edsall LC, Kono K, Poulton S, Milstien S, Kohama T, Spiegel S. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of a novel mammalian sphingosine kinase type 2 isoform. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:19513–19520. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002759200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Billich A, Bornancin F, Devay P, Mechtcheriakova D, Urtz N, Baumruker T. Phosphorylation of the immunomodulatory drug fty720 by sphingosine kinases. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:47408–47415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307687200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blondeau N, Lai Y, Tyndall S, Popolo M, Topalkara K, Pru JK, Zhang L, Kim H, Liao JK, Ding K, Waeber C. Distribution of sphingosine kinase activity and mrna in rodent brain. J Neurochem. 2007;103:509–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04755.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vlasenko LP, Melendez AJ. A critical role for sphingosine kinase in anaphylatoxin-induced neutropenia, peritonitis, and cytokine production in vivo. J Immunol. 2005;174:6456–6461. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Awad AS, Ye H, Huang L, Li L, Foss FW, Jr., Macdonald TL, Lynch KR, Okusa MD. Selective sphingosine 1-phosphate 1 receptor activation reduces ischemia-reperfusion injury in mouse kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290:F1516–1524. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00311.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gidday JM, Gasche YG, Copin JC, Shah AR, Perez RS, Shapiro SD, Chan PH, Park TS. Leukocyte-derived matrix metalloproteinase-9 mediates blood-brain barrier breakdown and is proinflammatory after transient focal cerebral ischemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H558–568. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01275.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tontsch U, Bauer HC. Isolation, characterization, and long-term cultivation of porcine and murine cerebral capillary endothelial cells. Microvasc Res. 1989;37:148–161. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(89)90034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Don AS, Martinez-Lamenca C, Webb WR, Proia RL, Roberts E, Rosen H. Essential requirement for sphingosine kinase 2 in a sphingolipid apoptosis pathway activated by fty720 analogues. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:15833–15842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609124200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foerch C, Wunderlich MT, Dvorak F, Humpich M, Kahles T, Goertler M, Alvarez-Sabin J, Wallesch CW, Molina CA, Steinmetz H, Sitzer M, Montaner J. Elevated serum s100b levels indicate a higher risk of hemorrhagic transformation after thrombolytic therapy in acute stroke. Stroke. 2007;38:2491–2495. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.480111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aird WC. Endothelium in health and disease. Pharmacol Rep. 2008;60:139–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bastide M, Gele P, Petrault O, Pu Q, Caliez A, Robin E, Deplanque D, Duriez P, Bordet R. Delayed cerebrovascular protective effect of lipopolysaccharide in parallel to brain ischemic tolerance. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:399–405. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000050064.57184.F2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dawson DA, Furuya K, Gotoh J, Nakao Y, Hallenbeck JM. Cerebrovascular hemodynamics and ischemic tolerance: Lipopolysaccharide-induced resistance to focal cerebral ischemia is not due to changes in severity of the initial ischemic insult, but is associated with preservation of microvascular perfusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:616–623. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199906000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masada T, Hua Y, Xi G, Ennis SR, Keep RF. Attenuation of ischemic brain edema and cerebrovascular injury after ischemic preconditioning in the rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:22–33. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200101000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Limaye V, Li X, Hahn C, Xia P, Berndt MC, Vadas MA, Gamble JR. Sphingosine kinase-1 enhances endothelial cell survival through a pecam-1-dependent activation of pi-3k/akt and regulation of bcl-2 family members. Blood. 2005;105:3169–3177. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sandoval KE, Witt KA. Blood-brain barrier tight junction permeability and ischemic stroke. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;32:200–219. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paik JH, Skoura A, Chae SS, Cowan AE, Han DK, Proia RL, Hla T. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor regulation of n-cadherin mediates vascular stabilization. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2392–2403. doi: 10.1101/gad.1227804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McVerry BJ, Garcia JG. In vitro and in vivo modulation of vascular barrier integrity by sphingosine 1-phosphate: Mechanistic insights. Cell Signal. 2005;17:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee JF, Zeng Q, Ozaki H, Wang L, Hand AR, Hla T, Wang E, Lee MJ. Dual roles of tight junction-associated protein, zonula occludens-1, in sphingosine 1-phosphate-mediated endothelial chemotaxis and barrier integrity. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29190–29200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604310200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schnitzer SE, Weigert A, Zhou J, Brune B. Hypoxia enhances sphingosine kinase 2 activity and provokes sphingosine-1-phosphate-mediated chemoresistance in a549 lung cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:393–401. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Connor P, Comi G, Montalban X, Antel J, Radue EW, de Vera A, Pohlmann H, Kappos L. Oral fingolimod (fty720) in multiple sclerosis: Two-year results of a phase ii extension study. Neurology. 2009;72:73–79. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000338569.32367.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kharel Y, Lee S, Snyder AH, Sheasley-O’neill SL, Morris MA, Setiady Y, Zhu R, Zigler MA, Burcin TL, Ley K, Tung KS, Engelhard VH, Macdonald TL, Pearson-White S, Lynch KR. Sphingosine kinase 2 is required for modulation of lymphocyte traffic by fty720. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:36865–36872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506293200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]