Abstract

Head and neck squamous cell carcinomas are among the most common neoplasms worldwide and characterized by local tumor aggressiveness, high rate of early recurrences, development of metastasis, and second primary cancers. Despite modern therapeutic strategies and sophisticated surgical management, overall survival-rates remained largely unchanged over the last decades. Thus, the need for novel treatment options for this tumor entity is undeniable. A key event in carcinogenesis is the uncontrolled modulation of genetic programs. Nuclear receptors belong to a large superfamily of transcription factors implicated in a broad spectrum of physiological and pathophysiological processes, including cancer. Several nuclear receptors have also been associated with head and neck cancer. This review will summarize their mode of action, prognostic/therapeutic relevance, as well as preclinical and clinical studies currently targeting nuclear receptors in this tumor entity.

1. Introduction

Most malignancies of the upper aerodigestive tract (Figure 1), comprising the naso-, oro-, hypo-, and laryngopharynx, are squamous cell carcinomas. Head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCCs) are the primary tumor type in head and neck cancer (HNC), characterized by local tumor aggressiveness, high rate of early recurrences, metastasis, and development of second primary tumors, which are the major cause of morbidity and mortality in HNSCC (details in [1–4]). More than 90% of HNC cases are induced by chronic exposure to carcinogens enclosed in all forms of tobacco, synergized by heavy alcohol consumptions and poor diet (see [5, 6]). It is estimated that about 5%–10% of suspicious lesions arising in the mucous membranes of the mouth, pharynx, and larynx undergo malignant transformation. Cure rates of early disease (stage I and II) range between 70% and 80%, and chemoprevention strategies seem promising to control potentially malignant oral lesions (reviewed in [1–3]). However, long-term survival rates, especially for advanced HNC, have not improved significantly over the last decades. Despite modern therapeutic strategies and sophisticated surgical management of the tumor, the estimated five-year survival rate for advanced disease (30%–40%) remains poor ([1–3] and references therein). Currently, rational therapeutic strategies targeting growth factor receptors by specific antibodies or kinase inhibitors have gained increasing clinical relevance in particular for the treatment of locally advanced cancer with the intent of preserving speech and swallowing (see [1–3]). Thus, developing new therapeutic strategies and defining novel target proteins for the treatment of advanced HNC is of particular importance.

Figure 1.

Schematic anatomy of the head and neck region. Head and neck cancer includes different types of malignancies that can develop in the mouth, nose and throat.

In this respect, nuclear receptors (NRs) are transcription factors implicated in cancer development and are recently attracting major interest as therapeutic targets (see [7, 8]). As NRs modulate cell proliferation, apoptosis, invasion, and migration, clearly representing hallmarks of cancer cells, several highly successful cancer drugs target this receptor family [8–11]. Since several NRs have been shown to be expressed also in head and neck cancer cells, NRs are most likely also contributing to HNSCC development and progression [12, 13].

NRs belong to a large superfamily of transcription factors and based on sequence comparison are currently classified into seven subfamilies (Table 1). These transcription factors are able to modulate transcription of a variety of target genes by several distinct mechanisms, including both transcriptional activation and repression [7, 8, 14, 15]. Transcriptional regulation can either be ligand-dependent or -independent, genomic or nongenomic, allowing NRs to mediate gene repression or its release, gene activation, or gene trans-repression (details in [7, 8, 16]). In particular, the large group of so-called orphan nuclear receptors, for which natural ligands are still unknown, do not exist at all (true orphans), or have only recently been identified (adopted orphans) is adding additional complexity to the field (Table 1) ([8, 17], and references within).

Table 1.

Current classification of the NR superfamily into subfamilies according to sequence homology. Trivial abbreviations are given in brackets. NRs implicated in head and neck tumorigenesis are given in bold; asterisks indicate orphan receptors.

| Subfamily | Full name | Subfamily members (trivial abbreviation) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subfamily 1 | Thyroid hormone receptor-like receptors | |||

|

| ||||

| Subgroups | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) α, β/δ, γ | ||

| Retinoic acid receptors | Retinoic acid receptor (RAR) α, β, γ | |||

| Retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptors | Retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor (ROR) α, β, γ | |||

| Rev-ErbA* | Rev-ErbA (EAR1) α, β | |||

| Thyroid hormone receptors | Thyroid hormone receptor (TR) α, β | |||

| Liver X receptor-like receptors* | Liver X receptor (LXR) α, β; Farnesoid X receptor (FXR) | |||

| Vitamin D receptor-like receptors | Vitamin D receptor (VDR); Pregnane X receptor (PXR); Constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) | |||

|

| ||||

| Subfamily 2 | Retinoid X receptor-like receptors | |||

|

| ||||

| Subgroups | Hepatocyte nuclear factor-4 | Hepatocyte nuclear factor-4 (HNF-4) α, γ | ||

| Retinoid X receptors | Retinoid X receptor (RXR) α, β, γ | |||

| Testicular receptors* | Testicular receptor 2, 4 (TR2/4) | |||

| Tailless-like receptors* | Human homologue of the Drosophila tailless gene (TLX); Photoreceptor cell-specific nuclear receptor (PNR) | |||

| Chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter-transcription factor-like receptors* | Chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter-transcription factor (COUP-TF) I, II; V-erbA-related (EAR2) | |||

|

| ||||

| Subfamily 3 | Estrogen receptor-like receptors | |||

|

| ||||

| Subgroups | Estrogen receptors | Estrogen receptor (ER) α, β | ||

| Estrogen related receptors* | Estrogen-related receptor (ERR) α, β, γ | |||

| 3-Ketosteroid receptors | Androgen receptor (AR); Progesterone receptor (PR);Glucocorticoid receptor (GR); Mineralocorticoid receptor (MR); | |||

|

| ||||

| Subfamily 4 | Nerve growth factor IB-like receptors | |||

|

| ||||

| Nerve Growth factor IB/ Nuclear receptor related/ Neuron-derived orphan receptor* | Nerve Growth factor IB (NGF-IB); Nuclear receptor related 1 (NURR1); Neuron-derived orphan receptor 1 (NOR1) | |||

|

| ||||

| Subfamily 5 | Steroidogenic factor-like receptors | |||

|

| ||||

| Steroidogenic factor/Liver receptor homolog* | Steroidogenic factor 1 (SF1); Liver receptor homologue-1 (LHR1) | |||

|

| ||||

| Subfamily 6 | Germ cell nuclear factor-like receptors | |||

|

| ||||

| Germ cell nuclear factor* | Germ cell nuclear factor (GCNF) | |||

|

| ||||

| Subfamily 0 | Miscellaneous receptors | |||

|

| ||||

| Dosage-sensitive sex reversal, adrenal hypoplasia critical region/Small heterodimer partner* | Dosage-sensitive sex reversal, adrenal hypoplasia critical region, on chromosome X, gene 1 (DAX); Small heterodimer partner (SHP) | |||

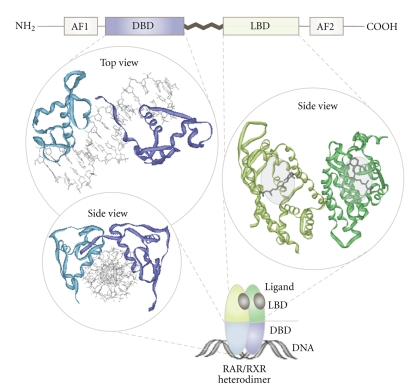

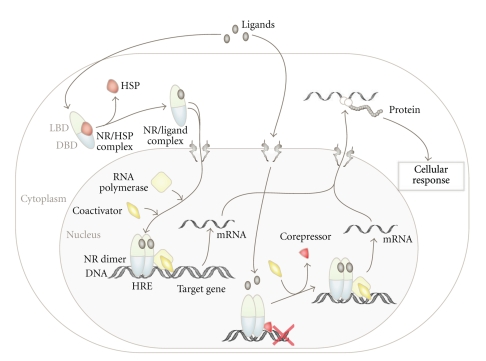

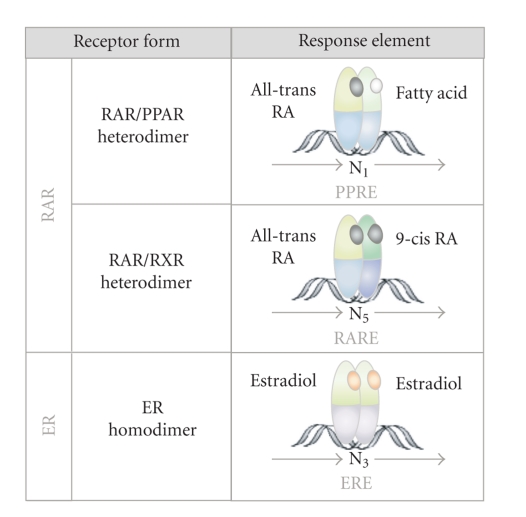

In contrast to cell surface growth factor receptors, such as the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), which activate genetic programs through complex intracellular signaling cascades, NRs are able to directly bind to specific DNA-sequences, so-called hormone response elements (HREs). Thus, NRs are composed of an N-terminal regulatory domain (activation function 1 = AF1), followed by a DNA-binding domain (DBD), a ligand-binding domain (LBD), and another C-terminal regulatory domain (activation function 2 = AF2) (Figure 2) [7, 8]. Despite their conserved structural organization, the biological functions of NRs are highly diverse. Nevertheless, two major modes of NR action can be assigned, depending on their intracellular steady-state localization in the absence of ligands (Figure 3). One group of NRs is confined to the cytoplasm within multiprotein-complexes in the absence of ligand. Upon ligand binding, they actively enter the nucleus and bind to HREs as homo- or heterodimers (Figure 4, details in [7, 8]). Other NRs already reside in the nucleus in a complex with corepressor proteins, while ligand binding triggers corepressor dissociation allowing the recruitment of coactivators [18, 19]. However, in order to fulfill multiple biological tasks minor to major deviations from these two modes of NR action exist [7, 8].

Figure 2.

Domain organization and structural binding modes of NRs. Upper panel: NRs are composed of an N-terminal regulatory domain (activation function 1 = AF1), followed by a DNA-binding domain (DBD), a ligand-binding domain (LBD), and a C-terminal domain (activation function 2 = AF2). Left panel: 3D model illustrating how the DBDs of the RAR/RXR heterodimer (PDB 1DSZ) interact with their target DNA-sequence. Right panel: solid ribbon representation illustrating the LBD of the RAR/RXR heterodimer (PDB 1DKF) complexed with the ligands 9-cis-RA for RXR (PDB 3LBD) and ATRA for RAR (PDB 2LBD). PDB files are taken from the RCBS Protein Data Bank (http://www.pdb.org/).

Figure 3.

Simplified model illustrating the two major modes of NR activation. Natural or synthetic ligands diffuse through the cell membrane and bind to cytosolic or nuclear NRs. Ligand binding to cytoplasmic NRs triggers conformational changes resulting in dissociation of heat shock proteins (HSPs) and receptor dimerization, allowing active nuclear import and transactivation by binding to HREs. Other NRs are constitutively nuclear and complexed with corepressors in the absence of ligands. Ligand binding induces conformational changes resulting in the recruitment of coactivators to activate transcription of target genes.

Figure 4.

DNA-binding modes of NRs implicated in HNSCC. RAR can heterodimerize with PPARs, which can be activated by lipophilic ligands. Alternatively, RARs are able to heterodimerize with RXRs, which are activated by 9-cis RA. Such heterodimers can bind to specific half-site retinoic acid (RARE) or peroxisome proliferator response elements (PPREs) direct repeats in the DNA of target genes. Estradiol binding induces estrogen receptor homodimerization and binding to palindromic half-site estrogen response element (ERE) inverted repeats. N: Any nucleotide occurring within the specific response element.

NRs are not only implicated in a broad spectrum of physiological processes but are associated with many human diseases including metabolic and cardiovascular disorders as well as cancer. Beside their proven clinical relevance for hormone regulated malignancies, there is rather limited information on their pathophysiological role as well as their prognostic and therapeutic potential for head and neck cancer [7, 8, 12, 20–22]. Most studies were investigating members of two classes of the NR superfamily, the thyroid hormone receptor-like and the estrogen receptor-like receptors (Table 1). Thus, we will focus on relevant members of these subfamilies, summarize their potential diagnostic/prognostic value, and discuss their therapeutic potential.

2. Thyroid Hormone Receptor-Like Receptors

2.1. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors

Within the thyroid hormone receptor-like receptor subfamily, the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) show the highest disease relevance for HNSCC. To date, three isoforms of the PPAR (α, β/δ, and γ) have been identified, all able to form heterodimers with retinoid X receptors (RXRs) (see [23, 24]). PPARs are expressed in different cell types and activate the transcription of several genes involved in a variety of biological processes, including lipid metabolism and insulin sensitivity (see [23, 24]). Furthermore, a role in limiting inflammation has also been reported [24, 25]. As tumor cell metabolism and inflammation appear to be critical for tumorigenesis and clinical outcome, NRs may thus directly or/and indirectly modulate malignancies [26, 27]. As such, PPARγ is overexpressed in many epithelial malignancies [22, 28, 29] including oral squamous cell carcinoma [30].

In the absence of ligand, PPARs are complexed with corepressor proteins, thus acting as transcriptional repressors. Ligand binding induces conformational changes facilitating heterodimerization with RXR, thus leading to the attraction of transcriptional coactivators (Figures 3 and 4) (see [19, 24]). Natural and synthetic ligands for PPARs include lipophilic molecules such as fatty acids and eicosanoids as well as thiazolidinedione (TZD) drugs and derivates thereof (overview in [7, 24, 31]). PPARγ ligands seem to exert their effects in a dosage-dependent manner [32], although the detailed mechanism is currently not yet resolved. The postulated cancer modulating mechanisms are diverse, including effects on Wnt signaling, inhibition of NFκB, as well as the modulation of cell cycle regulators and pro- and antiapoptotic proteins, which have been linked with head and neck cancer (see [4, 23]).

Clinical Aspects of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors in HNSCC —

In HNSCC, overexpression on the protein level has been convincingly demonstrated for PPARβ and PPARγ [12, 30, 33]. Agonist binding to PPARβ can induce cell differentiation, growth arrest, and apoptosis of cancer cells [34]. Additionally, such activating PPARβ ligands were shown to exert antiproliferative on human colon and breast cancers (details in [23, 24]) and were also suggested as potential chemopreventive agents for oral carcinogenesis [12, 35, 36]. Of note, since at least 1.6 million patients take antidiabetic drugs that function as PPARβ ligands, epidemiological data on their long-term effects on tumor prevention would therefore be of value to rationally design cancer chemoprevention trials.

Paradoxically, not only PPARγ agonists are considered as potential therapeutic agents in cancer therapy but also antagonists were studied in this respect [30]. PPARγ inhibition was shown to induce apoptosis and anoikis and inhibit tumor cell invasion in squamous cell carcinomas [30]. Moreover, the results of several studies indicated that the growth-inhibiting activity of PPARγ ligands in OSCC may be PPARγ independent [37]. Others showed that the observed effects were strongly dependent on PPARγ-expression [12, 38] as well as on the type and concentration of the agonist [39].

In the majority of OSCC cases, PPARγ mRNA could be detected by RT-PCR [37]. By immunohistochemical analysis of primary tumors, PPARγ was often found in low-grade tumors, especially in tumor endothelium [38], and a favorable impact of PPARγ expression on relapse-free survival of the patients could be demonstrated [40].

The beneficial effects of PPARγ ligands on malignancies were tested in several clinical trials, but outcomes proved to be highly diverse. Some trials revealed 40% partial response rates, whereas others could not show any significant beneficial effect [41, 42].

Moreover, one may speculate that the tumor modulating effects of PPARγ ligands are mediated indirectly by affecting the tumor microenvironment, such as cancer-associated fibroblasts or tumor endothelial cells [43]. In fact, PPARγ ligands have been shown to affect endothelial cell proliferation and migration and hence to regulate angiogenesis [44]. Also hypoxia-induced angiogenesis appears to be affected by PPARγ ligands in cancer therapy, even if the precise mechanisms still remain unclear [45]. As angiogenesis is a crucial aspect for tumor development, therapy resistance and metastasis and inhibition of angiogenesis may hence have contributed to the clinical benefit observed.

In sum, PPARγ ligands appear to be of clinical benefit for the treatment of head and neck cancer, in particular for OSCC. Nevertheless, a more detailed molecular knowledge on PPARγ biology is clearly required. Increasing knowledge about the mode of action, specificity, and dosage-dependence of PPAR agonistic and antagonistic ligands will hopefully allow a better modeling of PPAR receptor function and thus lead to a more effective design of combinatorial application schemes for cancer treatment and cancer prevention in the future.

2.2. Retinoid Acid Receptors

Another group of thyroid hormone receptor-like receptors implicated in HNSCC is the retinoid acid receptors (RARs). RARs are characterized by their activation via vitamin A derivatives. Upon activation, RARs are able to heterodimerize with retinoid X receptors (RXR) and to bind to specific hormone response elements (HREs), thereby modulating transcription of target genes (Figures 3 and 4) [8, 26, 46]. To date, a variety of coactivator- and corepressor-proteins have been identified, allowing the fine-tuning of target gene transcription, ranging from repression to full activation [18]. However, the molecular details are just beginning to be uncovered [8, 26, 46]. RAR activation often leads to differentiation [47], cell-cycle arrest [48], or apoptosis [49], culminating in the inhibiting of tumor growth. Hence, its ligand retinoid acid (RA) or derivates thereof are currently tested as therapeutic agents in several cancer types (Table 2) [50]. Paradoxically, in some malignancies RA rather promotes cell survival, which may be due to the ability of RA to also activate PPARs, and as a consequence expression of prosurvival genes is induced [46]. Schug et al. could also show that the channeling of RA between these two nuclear receptor heterodimers is mediated by the cytoplasmic RA transporters CRABP2 and FABP5 and thus is strongly depending on the FABP5/CRABP2 ratio [46]. Thus, the channeling of RA to different receptor heterodimers appears to be crucial for the regulation of cell-proliferation, positively or negatively affecting tumor growth [46]. Interestingly, both proteins were found differentially expressed in metastatic and HPV-associated HNSCC, but their biological and clinical effects remain to be investigated [51, 52].

Table 2.

Overview of current clinical trials in the field of HNSCC targeting NRs. The NCI protocol ID is given in bold (for further details see: http://www.cancer.gov/CLINICALTRIALS).

| NR | Clinical trial / identifier | Drug | Tumor entity | Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPAR | Pioglitazone in Preventing Head and Neck Cancer in Patients With Oral Leukoplakia/NCT00099021 | Pioglitazone | Head and Neck Cancer Precancerous/Nonmalignant Condition | Phase II ongoing |

| Rosiglitazone in Preventing Oral Cancer in Patients With Oral Leukoplakia/NCT00369174 | Rosiglitazone | Head and Neck Cancer Precancerous/Nonmalignant Condition | Phase II completed | |

|

| ||||

| RAR | Chemoprevention Study of Oral Cavity Squamous Cell Carcinoma/NCT00201279 | 13-cis Retinoic acid | Oral Cavity Squamous Cell Carcinoma | Phase III completed |

| Isotretinoin Plus Interferon in Treating Patients With Recurrent Cancer/NCT00002506 | Isotretinoin (combined with Interferon a) | Head and Neck Cancer Esophageal Cancer | Phase II ongoing | |

| Isotretinoin, Interferon Alpha, and Vitamin E in Treating Patients With Stage III or Stage IV Head and Neck Cancer/NCT00054561 | Isotretinoin (combined with Interferon a and Vitamin E) | Head and Neck Cancer | Phase III completed | |

|

| ||||

| ER | Combination Chemotherapy and Tamoxifen in Treating Patients With Solid Tumors/NCT00002608 | Tamoxifen (combined with Cisplatin and Doxorubicin) | Head and Neck Cancer | Phase II completed |

An additional way of biological regulation is epigenetic modulation playing an important role in cancer development (reviewed in [53]). Gene silencing caused by aberrant hypermethylation of CpG islands has not only been detected in promoter regions of several tumor suppressor genes [53], but several studies show hypermethylation of the RARβ promoter in colon, breast, and lung cancers [54, 55]. In head and neck carcinogenesis, hypermethylation of the RARβ promoter was found to be indeed associated with RARβ downregulation and hence appears to be biologically relevant [56].

Clinical Aspects of Retinoid Acid Receptors in HNSCC —

As outlined above, a rationale for the use of retinoids in chemoprevention and cancer therapy was provided experimentally by different cellular [57] and animal models [58]. Moreover, this strategy was supported by epidemiological data as well as by clinical trial outcomes [26, 59–61]. Several clinical chemoprevention trials including patients with increased risk for developing cancer have shown that treatment with retinoids resulted in the suppression of precancerous lesions (see [26, 60]). Also, certain retinoids inhibited the development of second primary tumors in patients who had been previously treated for an early-stage cancer but remained at high risk to relapse ([26, 60] and references within). However, other studies using isotretinoin or other retinoids (e.g., retinyl palmitate) did not observe any benefit in second primary tumor development, recurrence, or mortality of HNSCC or lung cancer [26, 62]. Current trials (Table 2) are therefore aiming to resolve these controversies by recruiting appropriate study populations as well as by the use of novel drugs and improved treatment protocols.

Reduced RARβ mRNA levels have been observed not only in several malignant tumors ([26, 56] and references therein) but also in premalignant oral lesions ([63] and references within). Unfortunately, until recently no antibodies convincingly detecting RARβ were available. Thus, most of the studies demonstrating RARβ downregulation were based on in situ hybridization and could therefore only show a decrease in the amount of mRNA. Ralhan et al. were the first to demonstrate decreased expression of the RXRα and RARα/β/γ on protein level correlating with different stages of OSCC development and progression [64]. The molecular mechanism leading to downregulation or loss of RARβ is poorly understood, but it was suggested that expression of RARβ could depend on the intracellular level of retinoids [26]. Several studies demonstrated a decrease in the amount of RARβ during vitamin A deficiency as well as its upregulation by RA. Additionally, there is evidence that retinoic acid induces the expression of RARβ mRNA in certain cell lines, but not in the malignant counterparts of these cells. Thus, transformed cells may have developed an aberrant response to retinoic acid due to the deregulated expression of coactivator/repressor proteins [26]. Ralhan et al. found a significant association between the increase in RARβ mRNA levels and clinical responses of premalignant oral lesions to isotretinoin [65, 66]. Hence, RARβ indeed seems to contribute to the suppression of the premalignant phenotype and malignancy and may be causally linked to the clinical outcome in chemoprevention trials with retinoids [26, 67]. If so, RARβ may indeed serve as a useful diagnostic marker in retinoid trials (Table 2) for the prevention of oral carcinogenesis [68]. RAR modulation by its agonist ligand all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) represents a successful example of how targeting of an NR contributes to an impressive clinical benefit in liquid tumors ([26] and references therein). Lessons learned from these studies clearly show that the therapeutic benefit could be further enhanced by combining ATRA with chromatin modulating agents, such as histone deacetylase inhibitors [69]. Nevertheless, the design of receptor specific drugs as well as an in depth understanding of the molecular regulation of RAR biology is required in order to fully exploit its therapeutic benefit and minimize potential side-effects in the area of head and neck cancer [7, 26].

3. Estrogen Receptor-Like Receptors

This subfamily is composed of the estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ), the estrogen-related receptor, and the 3-ketosteroid receptors [10].

Besides the estrogen receptors themselves, many of the genes regulated by the ER/estrogen-axis are critical for cell proliferation, inhibition of apoptosis, stimulation of invasion and metastasis, as well as for the promotion of angiogenesis (see [10, 11] and references within). Since these processes clearly state hallmarks of cancer cells, it is well accepted that ERs are implicated in various cancer types [9, 21]. Sex hormone receptors are expressed not only in sexual organs but, amongst others, also in the vascular epithelium [70], the lung epithelium [71], and the larynx [72]. The expression of sex hormone receptors could also be demonstrated in HNSCC by several studies [12, 13]. Both ER isoforms as well as the progesterone receptor (PR) were detectable in cancer cells of the oral cavity, the salivary gland, and in laryngeal/hypopharyngeal cancers, whereas the tumor stroma was mostly negative [12, 13]. Expression of ERα inversely correlated with that of ERβ in esophageal carcinoma, and a correlation of ERβ levels with tumor dedifferentiation and staging was suggested [73, 74].

Clinical Aspects of Estrogen Receptors in HNSCC —

Considering the impressive benefit of endocrine therapy in breast cancer, targeting sex steroid hormone receptor as a potential therapeutic strategy is also discussed for HNSCC [12, 75]. Currently, two main strategies are pursued in endocrine therapy of ER-positive tumors. One is based on steroidal antiestrogens like tamoxifen, which bind to the ER, block its function, and ultimately induce receptor degradation [8, 11]. The other is based on aromatase inhibitors and luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists, which reduce the level of circulating estrogen, thereby inhibiting ER activation by depriving the receptor of its ligand [11]. Tamoxifen was already shown to inhibit proliferation and invasion of HNSCC cell lines, resulting in apoptosis, which could be further enhanced upon combination with cisplatin [76–78]. Thus, a therapeutic role of antiestrogens or aromatase inhibitors in the clinical management of HNSCC is currently under investigation, and the results of just completed clinical trials (Table 2) are eagerly awaited.

However, the precise molecular roles and impact of estrogen receptor-like receptors for the onset and/or progression of head and neck cancer remain to be clarified. This knowledge will be required, in order to rationally decide whether to further investigate the potential of modern endocrine therapy also for this tumor entity.

4. Conclusion

NRs are associated with head and neck cancer and hence seem to be at least partially amenable for prevention and/or treatment strategies. So far, three NR groups have mainly been linked with HNSCC, the retinoic acid and the peroxisome proliferator-activated and the estrogen receptors. Also, target genes activated by these NR subfamilies (Table 3) have been implicated as key elements in the molecular circuits involved in head and neck cancer development and progression. Reports on other members of the NR superfamiliy are rather scarce for this tumor entity, suggesting that they have not been investigated so far. Taking the thyroid hormone receptor as an example, many studies on its relevance for various malignancies have been conducted, whereas its role in head and neck cancer, including even thyroid carcinomas, has not been analyzed in detail [79]. Likewise, data on the cancer-related biological functions of orphan NRs are still missing for this tumor entity [7, 8]. As now cancer cell metabolism is beginning to be considered as “cancer's Achilles' heel”, it may be conceivable to speculate that molecules present in diet, tobacco, or beetle nut might deregulate the cell's metabolism by affecting NRs and as such contribute to head and neck carcinogenesis [27, 80]. Of note, the development of novel NR ligands with improved specificity and activity is currently intensively pursued in the area of metabolic diseases (see [7, 8, 81]). Hence, an interdisciplinary exploitation of the existing knowledge of NR pharmacobiology may result in novel HNSCC treatment approaches.

Table 3.

Nuclear receptor target genes playing pivotal roles in diverse biological processes and cellular homeostasis were described to be differentially expressed in head and neck cancer.

| NR | Target gene | Function | Reference - target gene | Reference - head and neck |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPAR | G0S2 | Cell cycle | Zandbergen et al. Biochem J 2005 | Tokumaru et al. Cancer Res 2004 |

| PDK1 | Energy homeostasis | Degenhardt et al. J Mol Biol 2007 | Wigfield et al. Br J Cancer 2008 | |

|

| ||||

| RAR | p21WAF1/CIP1 | Cell cycle | Liu et al. J Biol Chem 1996 | Kapranos et al. Anticancer Res 2001 |

| BIRC5/surviving | Apoptosis | Pratt et al. J Cell Biochem 2003 | Engels et al. J Pathol 2007 | |

| C/EBPε | Transcription factor | Schwarz et al. Mol Cell Biol 1997 | Bennett et al. Cancer Res 2007 | |

| CRABP | Carrier protein | Nezzar et al. Mol Vis 2007 | Won et al. Metabolism 2004 | |

| cyclins, CDK | Cell cycle | Bour et al. Trends Cell Biol 2007 | Jeannon et al. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 1998 | |

|

| ||||

| ER | c-Myc | Transcription factor | Markaverich et al. Steroids 2006 | Pries et al. Int J Mol Med 2008 |

| Cyclins | Cell cycle | Eeckhoute et al. Genes Dev 2006 | Nakashima et al. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2005 Lotayef et al. Br J Cancer 2000 | |

| CRABP | Carrier protein | Li et al. J Biol Chem 2003 | Vo et al. Anticancer Res 1998 | |

| CXCl12/SDF-1 | Chemokine/ligand | Hall et al. Mol Endocrinol 2003 | Rehman et al. J Biol Chem 2008 | |

| cathepsin D | Protease | Bretschneider et al. Mol Oncol 2008 | Strojan et al. Anticancer Res 2000 | |

In sum, keeping in mind the enormous success of NR targeting therapeutics in several malignancies, a systematic investigation of NR biology as well as of its clinical relevance is highly desirable also for head and neck cancer. Together with the outcomes of current clinical trials (Table 2), such improved knowledge will hopefully result in strategies with improved benefit for the patient.

Acknowledgment

Research of the author is supported by the Peter und Traudl Engelhorn-Stiftung. The author apologizes to colleagues for omitting many worthy references due to space limitations.

References

- 1.Forastiere A, Weber R, Ang K. Treatment of head and neck cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358(10):1077–1078. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc073274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forastiere AA. Chemotherapy in the treatment of locally advanced head and neck cancer. Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2008;97(8):701–707. doi: 10.1002/jso.21012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernier J. A multidisciplinary approach to squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck: an update. Current Opinion in Oncology. 2008;20(3):249–255. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3282faa0b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lippert BM, Knauer SK, Fetz V, Mann W, Stauber RH. Dynamic survivin in head and neck cancer: molecular mechanism and therapeutic potential. International Journal of Cancer. 2007;121(6):1169–1174. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forastiere AA, Trotti A, Pfister DG, Grandis JR. Head and neck cancer: recent advances and new standards of care. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(17):2603–2605. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forastiere AA, Ang KK, Brizel D, et al. Head and neck cancers. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2008;6(7):646–695. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2008.0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gronemeyer H, Gustafsson J-Å, Laudet V. Principles for modulation of the nuclear receptor superfamily. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2004;3(11):950–964. doi: 10.1038/nrd1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schweitzer A, Knauer SK, Staubert RH. Therapeutic potential of nuclear receptors. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patents. 2008;18(8):861–888. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Cancer genes and the pathways they control. Nature Medicine. 2004;10(8):789–799. doi: 10.1038/nm1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dahlman-Wright K, Cavailles V, Fuqua SA, et al. International union of pharmacology. LXIV. Estrogen receptors. Pharmacological Reviews. 2006;58(4):773–781. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.4.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osborne CK, Schiff R. Estrogen-receptor biology: continuing progress and therapeutic implications. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(8):1616–1622. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamakawa H, Nakashiro K-I, Sumida T, et al. Basic evidence of molecular targeted therapy for oral cancer and salivary gland cancer. Head and Neck. 2008;30(6):800–809. doi: 10.1002/hed.20830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lukits J, Remenár É, Rásó E, Ladányi A, Kásler M, Tímár J. Molecular identification, expression and prognostic role of estrogen- and progesterone receptors in head and neck cancer. International Journal of Oncology. 2007;30(1):155–160. doi: 10.3892/ijo.30.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Germain P, Staels B, Dacquet C, Spedding M, Laudet V. Overview of nomenclature of nuclear receptors. Pharmacological Reviews. 2006;58(4):685–704. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.4.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trotter KW, Archer TK. Nuclear receptors and chromatin remodeling machinery. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2007;265-266:162–167. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perissi V, Rosenfeld MG. Controlling nuclear receptors: the circular logic of cofactor cycles. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2005;6(7):542–554. doi: 10.1038/nrm1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benoit G, Malewicz M, Perlmann T. Digging deep into the pockets of orphan nuclear receptors: insights from structural studies. Trends in Cell Biology. 2004;14(7):369–376. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michalik L, Wahli W. Guiding ligands to nuclear receptors. Cell. 2007;129(4):649–651. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nettles KW, Greene GL. Ligand control of coregulator recruitment to nuclear receptors. Annual Review of Physiology. 2005;67:309–333. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032802.154710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kourelis K, Sotiropoulou-Bonikou G, Vandoros G, Varakis I. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ expression correlates with the differentiation level of normal, premalignant, and malignant laryngeal squamous cells. Journal of Otolaryngology. 2007;36(5):283–290. doi: 10.2310/7070.2007.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deroo BJ, Korach KS. Estrogen receptors and human disease. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2006;116(3):561–570. doi: 10.1172/JCI27987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krishnan A, Nair SA, Pillai MR. Biology of PPAR gamma in cancer: acritical review on existing lacunae. Current Molecular Medicine. 2007;7(6):532–540. doi: 10.2174/156652407781695765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yasui Y, Kim M, Tanaka T. PPAR ligands for cancer chemoprevention. PPAR Research. 2008;2008:10 pages. doi: 10.1155/2008/548919. Article ID 548919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lehrke M, Lazar MA. The many faces of PPARγ . Cell. 2005;123(6):993–999. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsueh WA, Bruemmer D. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma: implications for cardiovascular disease. Hypertension. 2004;43(2):297–305. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000113626.76571.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altucci L, Leibowitz MD, Ogilvie KM, de Lera AR, Gronemeyer H. RAR and RXR modulation in cancer and metabolic disease. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2007;6(10):793–810. doi: 10.1038/nrd2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kroemer G, Pouyssegur J. Tumor cell metabolismml: cancer's Achilles' heel. Cancer Cell. 2008;13(6):472–482. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang T, Xu J, Yu X, Yang R, Han ZC. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in malignant diseases. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2006;58(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fajas L, Debril MB, Auwerx J. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptorgamma: from adipogenesis to carcinogenesis. Journal of Molecular Endocrinology. 2001;27(1):1–9. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0270001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masuda T, Wada K, Nakajima A. Critical role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ on anoikis and invasion of squamous cell carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research. 2005;11(11):4012–4021. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feldman PL, Lambert MH, Henke BR. PPAR modulators and PPAR pan agonists for metabolic diseases: the next generation of drugs targeting peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors? Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 2008;8(9):728–749. doi: 10.2174/156802608784535084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clay CE, Namen AM, Atsumi G-I, et al. Magnitude of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ activation is associated with important and seemingly opposite biological responses in breast cancer cells. Journal of Investigative Medicine. 2001;49(5):413–420. doi: 10.2310/6650.2001.33786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaeckel EC, Raja S, Tan J, et al. Correlation of expression of cyclooxygenase-2, vascular endothelial growth factor, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor δ with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Archives of Otolaryngology—Head & Neck Surgery. 2001;127(10):1253–1259. doi: 10.1001/archotol.127.10.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koeffler HP. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and cancers. Clinical Cancer Research. 2003;9(1):1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Badawi AF, Badr MZ. Chemoprevention of breast cancer by targeting cyclooxygenase-2 and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma. International Journal of Oncology. 2002;20(6):1109–1122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kopelovich L, Fay JR, Glazer RI, Crowell JA. Peroxisome proliferatoractivated receptor modulators as potential chemopreventive agents. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2002;1(5):357–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakashiro K, Begum NM, Uchida D, et al. Thiazolidinediones inhibit cell growth of human oral squamous cell carcinoma in vitro independent of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. Oral Oncology. 2003;39(8):855–861. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(03)00108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Panigrahy D, Singer S, Shen LQ, et al. PPARgamma ligands inhibit primary tumor growth and metastasis by inhibiting angiogenesis. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2002;110(7):923–932. doi: 10.1172/JCI15634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Panigrahy D, Shen LQ, Kieran MW, Kaipainen A. Therapeutic potential of thiazolidinediones as anticancer agents. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 2003;12(12):1925–1937. doi: 10.1517/13543784.12.12.1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Papadaki I, Mylona E, Giannopoulou I, Markaki S, Keramopoulos A, Nakopoulou L. PPARgamma expression in breast cancer: clinical value and correlation with ERbeta. Histopathology. 2005;46(1):37–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baetz T, Eisenhauer E, Siu L, et al. A phase I study of oral LY293111 given daily in combination with irinotecan in patients with solid tumours. Investigational New Drugs. 2007;25(3):217–225. doi: 10.1007/s10637-006-9021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kebebew E, Peng M, Reiff E, et al. A phase II trial of rosiglitazone in patients with thyroglobulin-positive and radioiodine-negative differentiated thyroid cancer. Surgery. 2006;140(6):960–967. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Whiteside TL. The tumor microenvironment and its role in promoting tumor growth. Oncogene. 2008;27(45):5904–5912. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang N. PPAR-δ in vascular pathophysiology. PPAR Research. 2008;2008:10 pages. doi: 10.1155/2008/164163. Article ID 164163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim EH, Surh YJ. The role of 15-deoxy-delta(12,14)-prostaglandin J(2), an endogenous ligand of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, in tumor angiogenesis. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2008;76(11):1544–1553. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schug TT, Berry DC, Shaw NS, Travis SN, Noy N. Opposing effects of retinoic acid on cell growth result from alternate activation of two different nuclear receptors. Cell. 2007;129(4):723–733. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rochette-Egly C. Nuclear receptors: integration of multiple signalling pathways through phosphorylation. Cellular Signalling. 2003;15(4):355–366. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(02)00115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Donato LJ, Suh JH, Noy N. Suppression of mammary carcinoma cell growth by retinoic acid: the cell cycle control gene Btg2 is a direct target for retinoic acid receptor signaling. Cancer Research. 2007;67(2):609–615. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Donato LJ, Noy N. Suppression of mammary carcinoma growth by retinoic acid: proapoptotic genes are targets for retinoic acid receptor and cellular retinoic acid-binding protein II signaling. Cancer Research. 2005;65(18):8193–8199. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Soprano DR, Qin P, Soprano KJ. Retinoic acid receptors and cancers. Annual Review of Nutrition. 2004;24:201–221. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.012003.132407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Uma RS, Naresh KN, D'Cruz AK, Mulherkar R, Borges AM. Metastasis of squamous cell carcinoma of the oral tongue is associated with downregulation of epidermal fatty acid binding protein (E-FABP) Oral Oncology. 2007;43(1):27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martinez I, Wang J, Hobson KF, Ferris RL, Khan SA. Identification of differentially expressed genes in HPV-positive and HPV-negative oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas. European Journal of Cancer. 2007;43(2):415–432. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baylin SB, Ohm JE. Epigenetic gene silencing in cancer—a mechanism for early oncogenic pathway addiction? Nature Reviews Cancer. 2006;6(2):107–116. doi: 10.1038/nrc1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Virmani AK, Rathi A, Zöchbauer-Müller S, et al. Promoter methylation and silencing of the retinoic acid receptor-β gene in lung carcinomas. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92(16):1303–1307. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.16.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sirchia SM, Ferguson AT, Sironi E, et al. Evidence of epigenetic changes affecting the chromatin state of the retinoic acid receptor β2 promoter in breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2000;19(12):1556–1563. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Youssef EM, Lotan D, Issa JP, et al. Hypermethylation of the retinoic acid receptor-β(2) gene in head and neck carcinogenesis. Clinical Cancer Research. 2004;10(5):1733–1742. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0989-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nason-Burchenal K, Gandini D, Botto M, et al. Interferon augments PML and PML/RARα expression in normal myeloid and acute promyelocytic cells and cooperates with all-trans retinoic acid to induce maturation of a retinoid-resistant promyelocytic cell line. Blood. 1996;88(10):3926–3936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shalinsky DR, Bischoff ED, Lamph WW, et al. A novel retinoic acid receptor-selective retinoid, ALRT1550, has potent antitumor activity against human oral squamous carcinoma xenografts in nude mice. Cancer Research. 1997;57(1):162–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hong WK, Spitz MR, Lippman SM. Cancer chemoprevention in the 21st century: genetics, risk modeling, and molecular targets. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2000;18(21, supplement):9s–18s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lippman SM, Lotan R. Advances in the development of retinoids as chemopreventive agents. Journal of Nutrition. 2000;130(supplement)(2):479S–482S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.2.479S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Germain P, Chambon P, Eichele G, et al. International union of pharmacology. LX. Retinoic acid receptors. Pharmacological Reviews. 2006;58(4):712–725. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.4.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van Zandwijk N, Dalesio O, Pastorino U, de Vries N, van Tinteren H. EUROSCAN, a randomized trial of vitamin A and N-acetylcysteine in patients with head and neck cancer or lung cancer. For the EUropean Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Head and Neck and Lung Cancer Cooperative Groups. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92(12):977–986. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.12.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McGregor F, Muntoni A, Fleming J, et al. Molecular changes associated with oral dysplasia progression and acquisition of immortality: potential for its reversal by 5-azacytidine. Cancer Research. 2002;62(16):4757–4766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ralhan R, Chakravarti N, Kaur J, et al. Clinical significance of altered expression of retinoid receptors in oral precancerous and cancerous lesions: relationship with cell cycle regulators. International Journal of Cancer. 2006;118(5):1077–1089. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ralhan R, Kaur J. Retinoids as chemopreventive agents. Journal of Biological Regulators and Homeostatic Agents. 2003;17(1):66–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lotan R, Xu X-C, Lippman SM, et al. Suppression of retinoic acid receptor-β in premalignant oral lesions and its up-regulation by isotretinoin. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1995;332(21):1405–1410. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505253322103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pavan B, Biondi C, Dalpiaz A. Nuclear retinoic acid receptor beta as a tool in chemoprevention trials. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2006;13(29):3553–3563. doi: 10.2174/092986706779026183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wrangle JM, Khuri FR. Chemoprevention of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Current Opinion in Oncology. 2007;19(3):180–187. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3280f01026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bug G, Ritter M, Wassmann B, et al. Clinical trial of valproic acid and all-trans retinoic acid in patients with poor-risk acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2005;104(12):2717–2725. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Venkov CD, Rankin AB, Vaughan DE. Identification of authentic estrogen receptor in cultured endothelial cells: a potential mechanism for steroid hormone regulation of endothelial function. Circulation. 1996;94(4):727–733. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.4.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Omoto Y, Kobayashi Y, Nishida K, et al. Expression, function, and clinical implications of the estrogen receptor β in human lung cancers. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2001;285(2):340–347. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Marsigliante S, Muscella A, Resta L, Storelli C. Human larynx expresses isoforms of the oestrogen receptor. Cancer Letters. 1996;99(2):191–196. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(95)04056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kalayarasan R, Ananthakrishnan N, Kate V, Basu D. Estrogen and progesterone receptors in esophageal carcinoma. Diseases of the Esophagus. 2008;21(4):298–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nozoe T, Oyama T, Takenoyama M, Hanagiri T, Sugio K, Yasumoto K. Significance of immunohistochemical expression of estrogen receptors α and β in squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Clinical Cancer Research. 2007;13(14):4046–4050. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vattemi E, Graiff C, Sava T, Pedersini R, Caldara A, Mandara M. Systemic therapies for recurrent and/or metastatic salivary gland cancers. Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy. 2008;8(3):393–402. doi: 10.1586/14737140.8.3.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ku TKS, Crowe DL. Coactivator-mediated estrogen response in human squamous cell carcinoma lines. Journal of Endocrinology. 2007;193(1):147–155. doi: 10.1677/JOE-06-0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Balakumar P, Rose M, Ganti SS, Krishan P, Singh M. PPAR dual agonists: are they opening Pandora's Box? Pharmacological Research. 2007;56(2):91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ishida H, Wada K, Masuda T, et al. Critical role of estrogen receptor on anoikis and invasion of squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Science. 2007;98(5):636–643. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00437.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rocha AS, Marques R, Bento I, et al. Thyroid hormone receptor β mutations in the ‘hot-spot region’ are rare events in thyroid carcinomas. Journal of Endocrinology. 2007;192(1):83–86. doi: 10.1677/JOE-06-0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hsu PP, Sabatini DM. Cancer cell metabolismml: warburg and beyond. Cell. 2008;134(5):703–707. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Biggins JB, Koh JT. Chemical biology of steroid and nuclear hormone receptors. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2007;11(1):99–110. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]