Abstract

This study used data from 6 sites and 3 countries to examine the developmental course of physical aggression in childhood and to analyze its linkage to violent and nonviolent offending outcomes in adolescence. The results indicate that among boys there is continuity in problem behavior from childhood to adolescence and that such continuity is especially acute when early problem behavior takes the form of physical aggression. Chronic physical aggression during the elementary school years specifically increases the risk for continued physical violence as well as other nonviolent forms of delinquency during adolescence. However, this conclusion is reserved primarily for boys, because the results indicate no clear linkage between childhood physical aggression and adolescent offending among female samples despite notable similarities across male and female samples in the developmental course of physical aggression in childhood.

Children’s behavior problems have long been considered precursors of juvenile delinquency and adult criminality (Carpenter, 1851; Horn, 1989; Roosevelt, 1909). The development of these behavior problems during the elementary school years was the object of intensive investigations over the last quarter of the 20th century. A number of large-scale longitudinal studies in different industrialized countries used repeated measurements over many years to trace the development of behavior problems. These studies followed older pioneering longitudinal studies that were retrospective (e.g., Robins, 1966) or that had limited their prospective assessments to one time point during childhood and one or two time points during adolescence and adulthood (e.g., Lefkowitz, Eron, Walder, & Huesmann, 1977; West & Harrington, 1973).

Having reviewed this long-lived literature, the U.S. National Research Council’s Panel on Understanding and Preventing Violence concluded, “[I]t is clear that aggressive children tend to become violent teenagers and adults” (Reiss & Roth, 1993, p, 358). There is indeed ample evidence that, at least for boys, childhood disruptive or troublesome behavior is one of the best predictors of adolescent and adult criminality, including violent offending (e.g., Farrington, 1994; Fergusson & Horwood, 1995; Huesmann, Eron, Lefkowitz, & Walder, 1984; Moffitt, 1990; Pulkkinen & Tremblay, 1992; Stattin & Magnusson, 1989; Tremblay, Pihl, Vitaro, & Dobkin, 1994). However, Nagin and Tremblay (1999) and Tremblay (2000) pointed out that extant research generally does not distinguish physical from nonphysical aggression or violence. Thus, it is only possible to conclude that disruptive or troublesome behavior during childhood predicts later delinquent behavior, not that physical aggression during childhood per se is a distinct risk factor for physical violence in adolescence or adulthood.

A determination of whether physical aggression is a distinct risk factor for later physical violence is important for both conceptual and practical reasons. Conceptually, the nature of the link between childhood physical aggression and adult physical violence is a central issue in developmental theory and research on violence. It remains unclear whether physical violence is one manifestation of a general antisocial tendency or, conversely, whether the developmental dynamics of physical violence are unique and thereby theoretically and empirically distinguishable from other antisocial behaviors (Lahey et al., 1998; Nagin & Tremblay, 1999; Reiss & Roth, 1993; Rutter, Giller, & Hagell, 1998). In practical terms, physical aggression and violence are probably the most feared and socially costly of the behavior disorders. A clearer understanding of the origins of physical violence can advance the development of intervention techniques. If physical aggression is a distinct risk factor for later physical violence, screening strategies that focus on physical aggression rather than on generic troublesome behavior could increase predictive accuracy. Practitioners may be able to develop more effective preventive and corrective interventions by targeting the specific mechanisms that lead to and sustain physical aggression.

Recently, Nagin and Tremblay (1999) addressed the question of whether childhood physical aggression per se is a distinct risk factor for later violence among a sample of high-risk boys from Montreal, Canada. Using semi parametric modeling strategies, they mapped the developmental course of childhood disruptive behaviors in this sample and then used these developmental trajectories to predict later delinquent behavior. Their analysis identified four distinct developmental trajectories for childhood physical aggression as well as for childhood opposition and hyperactivity. Some boys exhibit virtually no disruptive behaviors, whereas most of the boys in this sample exhibited initially low or high levels of disruptive behaviors that declined with age. However, for each disruptive problem behavior, Nagin and Tremblay also identified a small but discernible group of boys who engaged in chronic levels of disruptive behavior over time. These groups are of particular importance because their chronic childhood disruptive behavior appears to place them at significant risk for later delinquency. Moreover, Nagin and Tremblay found that, with chronic opposition and hyperactivity controlled for, chronic physical aggression in childhood was a distinct predictor of the most serious and violent delinquency in adolescence. These results add to our understanding of the etiology of violence, suggesting that early physical aggression is, in fact, a distinct risk factor for later violent offending independent of other disruptive behavior problems. It is this hypothesis that we examine in more detail in the current study.

This study reports findings from a set of analyses aimed at assessing the robustness of the linkage between childhood physical aggression and adolescent delinquency, both cross-nationally and across sex. As Nagin and Tremblay (1999) indicated, their culturally homogeneous sample included only White francophone boys, thereby limiting its generalizability. The current study addresses this limitation because the data come from six data sets in three countries—two each from Canada, New Zealand, and the United States. As a basis for comparison, we included in this study the sample of Montreal boys used by Nagin and Tremblay (1999) in their initial investigation into the link between trajectories of disruptive behavior and later delinquency. For this site, along with the other five, we modeled and compared the developmental course of childhood physical aggression and assessed its linkage to violent and nonviolent delinquency in adolescence. Throughout the article, we compare results across sites and across sex to assess the robustness of the hypothesized link between physical aggression in childhood and delinquency in adolescence.

In comparing these models across sites, we were interested in identifying heterogeneity in the developmental course of physical aggression. In particular, we wanted to determine whether physical aggression generally develops in accordance with the four-group trajectory model identified by Nagin and Tremblay (1999) or whether there is variability cross-nationally and/or across sex in developmental pathways of physical aggression. Hence, we examined the distribution of childhood physical aggression into distinct developmental pathways and the degree to which these pathways tended to increase, decrease, or remain stable over age. In addition, we were especially interested in the degree to which analyses would reveal a chronically aggressive trajectory that was comparable across samples with distinct social-demographic characteristics and whether such a group would exist among female samples. This area of inquiry was of import because we hypothesized that such a trajectory would be linked to especially high levels of both violent and nonviolent delinquency in adolescence. We used regression models to examine the linkage between physical aggression trajectories and later violent and nonviolent delinquency.

Method

Data and Measures

A key strength of this study lies in the quality and comparability of the six data sets. Each data set involves an age cohort for whom data are available from as early as birth. In all data sets, longitudinal data on disruptive behavior problems were collected beginning between the ages of 5 and 7 years. Of the six sites, all but Montreal and Pittsburgh have data for girls as well as boys, allowing comparisons across sex. Across sites, these data include comparable and repeated measures of teacher-reported physical aggression beginning approximately at school entry and continuing through early adolescence. We used these data to examine the developmental course of this behavior across sites and sex. In addition, with the exception of Pittsburgh, each data set has comparable self-report measures of violent and nonviolent delinquency initially collected when cohort members reached their teenage years, allowing us to explore the linkage between early physical aggression and adolescent delinquency. Moreover, all of the data sets include repeated measures of childhood opposition and hyperactivity, and all of the data sets except the Christchurch Health and Development Study and the Child Development Project (CDP) include repeated measures of serious (but nonphysically aggressive) conduct problems. These data allowed us to introduce controls for comorbid disruptive behaviors in our analysis of the linkage between childhood trajectories of physical aggression and later delinquency.

A detailed description of the measures is provided in Appendix A (see Tables A1 and A2) along with their descriptive statistics (see Tables A3 through A9). Here we provide a brief description of each of the six data sets and the measures:

Montreal sample (Canada)

In the spring of 1984, all teachers of kindergarten classes at 53 schools in low socioeconomic areas in Montreal, Canada, were asked to rate the behavior of each boy in their classrooms. A total of 1,161 boys were rated by 87% of the kindergarten teachers for this high-risk, school-based sample. In order to control for cultural effects, the boys were included in the longitudinal study only if both of their biological parents were born in Canada and their parents’ mother tongue was French. Thus, a homogeneous Caucasian, French-speaking sample was created. The sample was reduced to 1,037 boys after applying these criteria and eliminating those who refused to participate and those who could not be traced. Following the assessment at age 6, the boys were then assessed annually from ages 10 to 17 years.

Quebec provincial sample (Canada)

This school-based sample comprises both girls and boys, about 1,000 of each, who were selected randomly from children attending kindergarten in the Canadian province of Quebec in 1986–1987. Yearly assessments of the children’s behavior and family life were obtained from mothers and teachers as the children aged from 6 to 12 years. The boys and girls were interviewed at 15 years of age. Another round of interviewing should begin within the next year.

Christchurch Health and Development Study (New Zealand)

The Christchurch Health and Development Study is a longitudinal study of an unselected birth cohort of 1,265 children (635 boys and 630 girls) born in the Christchurch, New Zealand, urban region during mid-1977. These children have now been studied at birth, 4 months, annually from age 1 to age 16, and again at age 18, using information gathered from a combination of sources including parental interview, teacher report, self-report, standardized psychometric testing, and medical and other official records.

Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study (New Zealand)

This study is an investigation of the health, development, and behavior of a complete cohort (N = 1,037; 535 boys and 502 girls) of consecutive births between April 1, 1972, and March 31, 1973, in Dunedin, New Zealand. The study participants are predominately of European origin and are representative of the ethnic and social class distribution of New Zealand’s South Island. The Dunedin sample has been repeatedly assessed with a diverse battery of psychological, sociological, and medical measures since the children were 3 years old. The latest assessment was at age 26.

Pittsburgh Youth Study (United States)

The Pittsburgh Youth Study is an investigation of delinquency, substance use, and mental health problems in a high-risk, stratified sample. Participants are 1,517 boys who initially were in Grades 1, 4, or 7 at the beginning of the study. Since that time, the youngest and the oldest samples have been regularly followed up over 12 years. The middle sample was discontinued after seven assessments. About half of the sample is African-American, and the other half is Caucasian. Assessments have included three informants–the boys, their parents, and their teachers–and cover a great variety of risk and protective factors.

Child Development Project (CDP; United States)

The CDP is an ongoing, multisite longitudinal study of children’s and adolescent’s adjustment. Five hundred eighty-five families (52% boys; 17% African American, 2% other minorities) were initially recruited from three geographical areas (Nashville and Knoxville, Tennessee, and Bloomington, Indiana) during kindergarten preregistration in the summers of 1987 and 1988. On a yearly basis, children, parents, and teachers have provided data on an array of developmentally relevant risk and protective factors.

As is evident in Tables A1 and A2 in Appendix A, measures of teacher-reported physical aggression comprise comparable items across sites, as do measures of self-reported violent and nonviolent delinquent outcomes. Despite some differences in the number of items in physical aggression scales across sites, these scales all reflect the same general behavioral tendencies across sites. Physical aggression scales range from two to five items and in all instances reflect children’s tendencies to use physical force in interactions with others. There is more variability in the items making up the opposition, hyperactivity, and serious (nonphysically aggressive) conduct problems scales across sites. Because these behaviors were included solely as controls in the regression analyses, such variability is of less import. We used these data to examine the extent to which any apparent link between childhood physical aggression and adolescent delinquency would hold when controls for potentially comorbid disruptive behaviors were introduced. Although the scales for these comorbid behaviors are not entirely comparable across sites because they are drawn from distinct sources (Canadian samples: Social Behavior Questionnaire, Tremblay et al., 1991; New Zealand samples: the Rutter child scales, Rutter, Tizard, & Whitmore, 1970, and Conners, 1969, 1970; U.S. samples.’ the Child Behavior Checklist [CBCL], Achenbach, 1991, and Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1983; the Teacher Report Form, Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1986, 1987), they do reflect similar behavioral tendencies. Opposition scales range from three to five items indicating a tendency toward non-physically aggressive but nonetheless defiant and antisocial behavior in interactions with others. Hyperactivity scales range from two to five items across sites. The items reflect a tendency toward disruptive motor activity as opposed to antisocial externalizing behavior. Finally, nonphysically aggressive conduct problems scales range from three to four items reflecting a tendency toward serious, but nonphysically aggressive, problem behaviors.

Outcome measures, derived from self-reports of violent and nonviolent delinquent involvement, are also characterized by cross-Site variation in the number of items but, as with the measures of externalizing behavior, reflect similar behavioral tendencies across sites. For all sites, respondents were asked to indicate whether they had ever engaged in each of the various behaviors listed in Table A2 (see Appendix A). Individual scores represent the sum of items for which respondents indicated involvement. Items included in the violent delinquency scales reflect those delinquent behaviors associated with physical violence and related person-based offenses. Items included in the nonviolent delinquency scales primarily reflect offenses against property rather than persons. The only clearly ambiguous behavior is weapons carrying, which was not measured in the CDP sample, was considered an indicator of nonviolent delinquency in the Dunedin sample, and was considered an indicator of violent delinquency in the three remaining samples. Although such cross-site inconsistencies do pose a problem for cross-site research such as the present study, the striking degree of cross-site measurement consistency seems more notable than the limited inconsistencies.

An examination of the descriptive statistics points to some important similarities and differences in the distribution of these behaviors and related trends across sex and across sites. Across sites and behaviors, mean disruptive behavior scores are normalized on a scale ranging from a minimum of 0 to a maximum of 2. As can be seen in Tables A3 through A8 in Appendix A, across sex, mean scores for physical aggression as well as for the other disruptive behaviors are higher for boys than girls, as are mean scores for self-reported violent and nonviolent offending. Longitudinally, trends in the distribution of disruptive behaviors over time differ across sites. In general, in the Canadian samples, mean disruptive behavior scores show declines over time, whereas in the New Zealand samples, mean disruptive behavior scores are primarily stable over time, and in the U.S. samples, mean disruptive behavior scores tend to show increasing means over time.

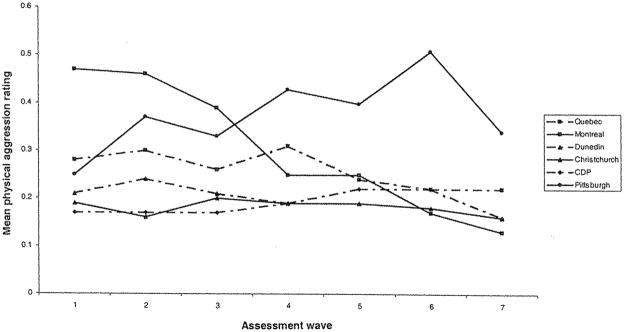

Figure 1 illustrates these general trends; it shows trends for mean physical aggression scores across sites for boys. As with disruptive behaviors more generally, physical aggression among boys shows longitudinal patterns of growth in the U.S. samples, stability in the New Zealand samples, and decline in the Canadian samples. Such differences could be attributed to various factors. In particular, they could reflect inherent cultural differences across sites, cohort differences introduced by the differing decades during which various data collection efforts began, differing sampling strategies across sites (i.e., birth cohort, school sample, high-risk/stratified sample), or more subtle cross-site differences in measurement procedures and/or indicators of disruptive behavior. It is not possible to unpack the contributions of each of these potential explanations to the differences in trends across sites. Still, the differences are subtle and in our judgment do not jeopardize the comparability of the data across sites. Indeed, the general stability across sites serves to increase our confidence in their comparability. Moreover, it is important to note that such trends represent aggregate patterns that mask potential similarities and differences across particular groups following distinct developmental trajectories. For instance, although aggregate patterns show some divergence across sites and sex, it is conceivable that, for all samples, a chronic physical aggression trajectory exists that follows a markedly similar developmental pattern across sites and sex. We used a semiparametric modeling strategy that allowed us to examine variation in developmental trajectories of physical aggression across sites for boys and girls.

Figure 1.

Physical aggression trends for boys. CDP = Child Development Project.

Estimation of Developmental Trajectories

To conduct our analyses, we used the same group-based, semiparametric methodology for estimating developmental trajectories that was used by Nagin and Tremblay (1999). One of the principal advantages of this methodology is that it is well suited for analyzing questions about developmental trajectories that are inherently categorical—for example, do certain types of people tend to have distinctive developmental trajectories? Another useful feature of the trajectory estimation method is that it is well suited for identifying heterogeneity in types of developmental trajectories rather than assuming it. Finally, this method uses a maximum likelihood procedure that accounts for the censored normal distribution of physical aggression and other disruptive behaviors that exhibit a large cluster at the scale minimum and a smaller but notable cluster at the scale maximum. Here we provide only a brief summary of the method. For details of the specific form of the methodology used here, see Nagin and Tremblay (1999) or Nagin (1999).

A developmental trajectory describes the progression of a given behavior as individuals age. A quadratic relationship is used to model the link between age and behavior:

| (1) |

where is a latent variable characterizing the behavior (e.g., physical aggression) of subject i at time t given membership in group j, Ageit is subject i’s age at time t, is the square of subject i’s age at time t, and ε is a disturbance assumed to be normally distributed with zero mean and constant variance (σ2).1 The model’s coefficients, , and , determine the shape of the trajectory. They are superscripted by j to denote that the coefficients are not constrained to be the same across the j groups. By freeing the model parameters to differ across groups, the estimation procedure allows for cross-group differences in the shape of developmental trajectories. This flexibility is a key feature of the model because it allows for easy identification of population heterogeneity not only in the level of behavior at a given age but also in its development over age.

Model estimation results in three key outputs: (a) the shape of each group’s trajectory as determined by the parameter estimates of Equation I, (b) the estimated proportion of the population belonging to each trajectory group, and (c) for each individual in the estimation sample, an estimate of the probability that he or she belongs to each of the trajectory groups identified in estimation (posterior probability of group membership).

Model selection requires a determination of the number of groups that best describes the data and the shape of the trajectory for each of those groups. As described in D’Unger, Land, McCall, and Nagin (1998), determination of the optimal number of groups is a difficult statistical problem. As recommended in D’Unger et al., we used the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) to select the optimal model. Specifically, we selected the model with the largest BIC from among multiple models reflecting variations in both the numbers of groups and the shape of the trajectories for each group. With this approach, the best fitting model reflects the model with the optimal number of groups, and it indicates the most likely longitudinal change trend for each of those groups. The change trends identified in the optimal model generally, though not always, are significant according to conventional T statistics. Further, even in those limited cases in which the change trend for a given group identified by the optimal model is not statistically significant, this trend is apparent in the data. In other words, the trends identified by the model, whether statistically significant or not, are evident in graphs of the trajectories. In no instance does the optimal model reflect a change trend that is disconfirmed in graphic representations of the model.

Analysis of the Linkage Between Trajectory Group Membership and Delinquency

To test the linkage between trajectories of childhood physical aggression and self-reported violent and nonviolent delinquency in adolescence, we examined the relationship between self-reported delinquency and the posterior probabilities of group membership for varying trajectories of physical aggression. For each individual in the sample, these probabilities estimate the probability of the individual’s belonging to each trajectory group. For example, consider a boy who persistently received high physical aggression ratings by teachers. For this individual, the posterior probability estimate of his belonging to the low trajectory group would be near zero, whereas the estimate of his belonging to the chronic group would be high. Individuals were assigned to the group with the largest posterior probability estimate.

We used regression methods to explore the relationship between childhood physical aggression group membership and subsequent adolescent delinquency. We also used multivariate models to test the robustness of this relation, controlling for potentially comorbid disruptive behaviors (opposition, hyperactivity, and serious [nonphysically aggressive] conduct problems). Delinquency measures reflect data collected after the final assessment of childhood disruptive behaviors used in the trajectory models. These measures reflect early adolescent delinquency for the Quebec and the CDP samples (age 13 for both) and delinquency in later adolescence for the Montreal (age 17) as well as the Dunedin and Christchurch samples (age 18 for both). Hence, we use the general term adolescence to refer to the teenage years as reflected in our outcome measures, but we recognize distinctions between early and late adolescence where appropriate.

To perform these analyses, we relied on the estimates of the posterior probability of group membership for each individual, based on the best-fitting trajectory models for physical aggression and other disruptive behaviors. These posterior probabilities of group membership served as independent variables in regression models assessing the relationship between group membership and delinquency. In entering the posterior probabilities as independent variables reflecting the influence of a given disruptive behavior, we entered the probabilities for all but one group (the “never” group) as independent variables. The exclusion of the probability of group membership for one of the groups is necessary because the posterior probabilities of group membership in each group will add to 1 for a given individual (e.g.. the independent variables would be perfectly correlated). To assess the influence of the behavior itself as opposed to the influence of a specific trajectory group, we then tested the significance of the joint influence of these probabilities on the dependent variable.

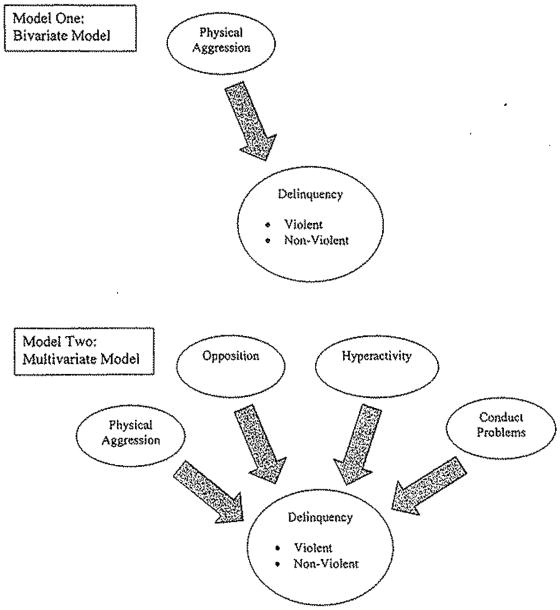

We assessed the influence of childhood physical aggression on later delinquency by estimating the two distinct regression models depicted in Figure 2. Model 1 examines the bivariate linkage between physical aggression and later delinquency. Even though the model includes multiple probabilities of membership as right-hand-side regressors, the probabilities pertain only to physical aggression. Our purpose was to test whether there was a significant bivariate relationship between group membership for physical aggression and, respectively, adolescent violent and nonviolent delinquency. This test would establish whether the developmental course of physical aggression can, by itself, predict delinquency. If, for example, childhood physical aggression predicts delinquency in adolescence, we would expect individuals with higher probabilities of belonging to groups with trajectories displaying higher levels of sustained physical aggression to be more prone to delinquency. We used the likelihood ratio test to test whether the group membership probabilities had such a statistically significant joint explanatory power. Hence, although this is not technically a bivariate model because it has from two to three independent variables depending on the sample, we used it to evaluate the bivariate relationship between physical aggression and each specific outcome.

Figure 2.

Bivariate and multivariate regression models.

Model 2 introduces controls for potentially comorbid disruptive behaviors into the model. In this model, we included the group membership probabilities for all disruptive behaviors. Our testing strategy was to examine whether any bivariate relation between physical aggression in childhood and delinquency in adolescence remained significant once controls for other, potentially comorbid, disruptive behaviors were included in the analysis. Again, we performed these tests of the joint significance of the group membership probabilities for each disruptive problem behavior using the likelihood ratio test.

Because the response variable measures a count (i.e., number of events), the models were estimated using a generalization of the standard Poisson regression procedure, the negative binomial model. Like the Poisson model, the negative binomial regression model is designed for analysis of count data. It generalizes the Poisson by accounting for the “overdispersion” problem, a common phenomenon in highly skewed data such as counts of individual criminal events (Land, McCall, & Nagin, 1996).

Results

Trajectories of Externalizing Behavior

Because the central aim of this study was to test whether physical aggression is a distinct risk factor for later violent delinquency, we begin by describing physical aggression trajectories for boys at each site. The models we present are based on teacher reports of physical aggression at all sites. Mother reports of externalizing behaviors were also available at most sites. Results based on mother reports of these behaviors are not materially distinct.

Male physical aggression

We begin first with a description of the best-fitting trajectory models for boys. Figures 3 through 8 display the models for trajectories of male physical aggression at each site. For all sites, determination of the best-fitting model was based on the BIC as described earlier.

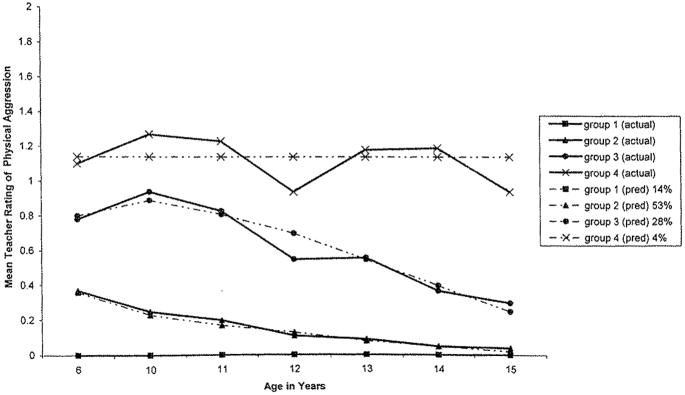

Figure 3.

Montreal: Male trajectories of physical aggression. pred = predicted.

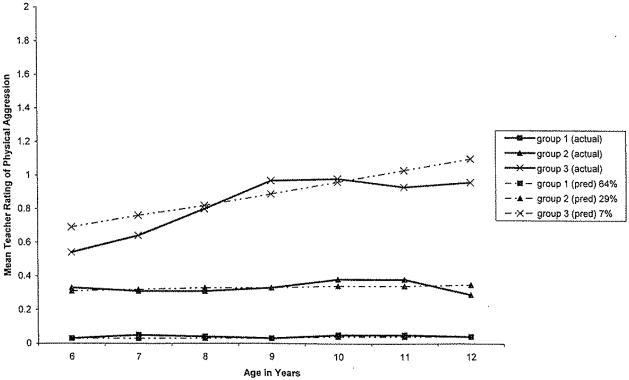

Figure 8.

Child Development Project: Male trajectories of physical aggression. pred = predicted.

Figure 3 reports the results for the Montreal sample used in Nagin and Tremblay’s (1999) single-site study. Four distinct developmental pathways were identified. There is a small group of individuals (14%) who almost never engage in physical aggression. The behavior of this group exhibits absolute stability—that is, little to no change in behavior over time. There is a similarly stable but even smaller group (4%) who engage in consistently high levels of physical aggression over time. The bulk of the sample falls into one of two declining trajectory groups. Those in the largest group (53%) engage in some physical aggression early on and desist to almost zero over time. A second group, representing 28% of the sample, engages in physical aggression at a rate nearly equal to that of the chronics at age 6 but tapers off thereafter. This group, while desisting over time, still displays some physical aggression at age 15. Evidence of absolute stability is limited. Only the two smallest groups—the never and chronic groups—show no evidence of changing levels of physical aggression. There is, however, substantial evidence of rank stability. Change in relative ranking would be evidenced by trajectories intersecting. The point of intersection would demarcate the age at which the two groups change relative rank. None of the trajectories intersect.

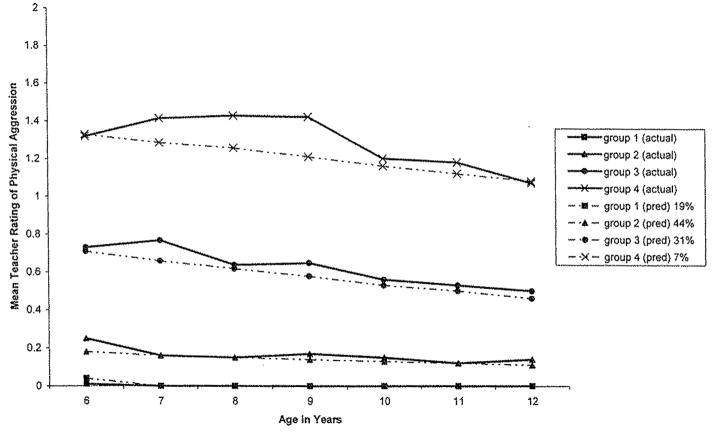

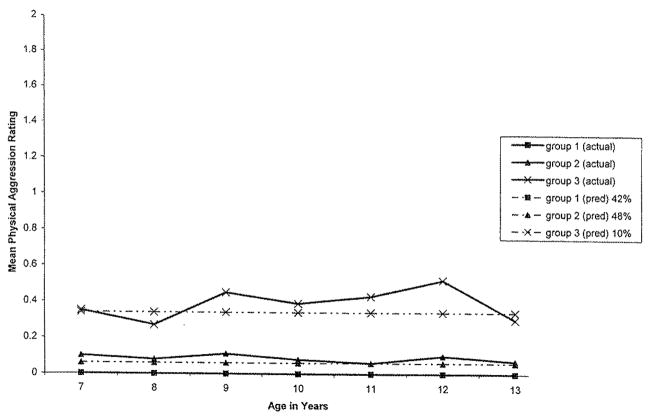

Figure 4 reports the model for the representative sample of boys from the Canadian province of Quebec. This model also identifies four distinct developmental trajectories for physical aggression. In this model, there is a small group of chronic offenders (7% of the sample), who, despite a declining trajectory, continue to exhibit relatively high levels of physical aggression over time. There is also a small group of boys who exhibit little physical aggression over time. This group accounts for 19% of the sample. The remaining two groups, who comprise the vast majority of the sample, reflect a pattern of decreasing physical aggression over time, similar to the patterns observed in the high- and low-level desister trajectories in the Montreal sample.

Figure 4.

Quebec: Male trajectories of physical aggression. pred = predicted.

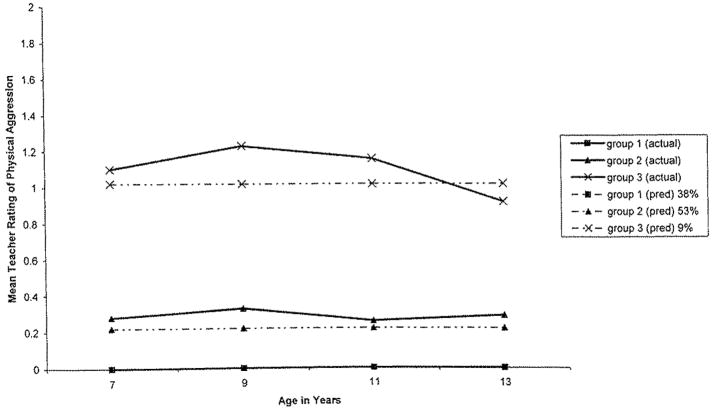

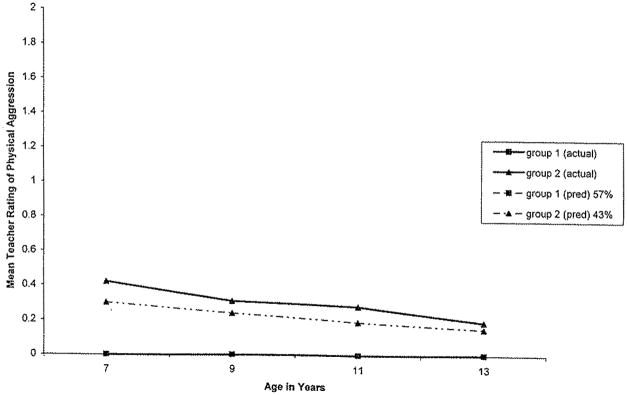

Figure 5 reports results for boys in the Christchurch, New Zealand, sample. Here a three-group model best represents the developmental pathways of physical aggression. The majority of boys in this sample (57%) follow a stable trajectory of little physical aggression. There is also a small chronically, aggressive group (11%) that displays a relatively high level of physical aggression that is stable over time. The remaining 32% of the sample follow a trajectory reflecting a stable pattern of low-level physical aggression over time.

Figure 5.

Christchurch: Male trajectories of physical aggression. pred = predicted.

Physical aggression in the sample of boys from Dunedin, New Zealand, is also best represented by a three-group model. See Figure 6. Also, like the Christchurch sample, all of the trajectories are stable. A majority of boys (53%) exhibit little to no physical aggression. Conversely, a small group of boys (9%) exhibit consistently high levels of physical aggression over time. The remainder of the boys (38%) exhibit a low but constant level of physical aggression.

Figure 6.

Dunedin: Male trajectories of physical aggression. pred = predicted.

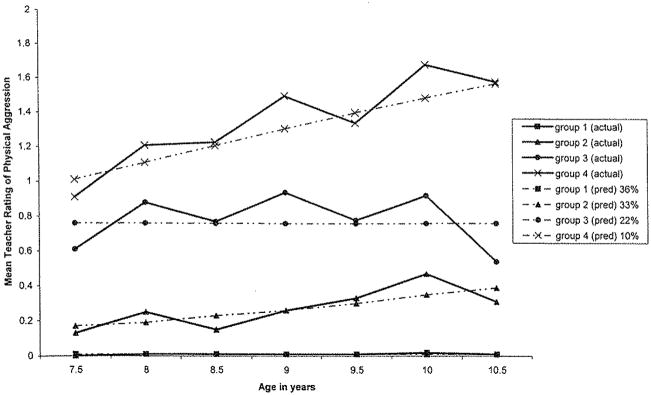

The boys in the Pittsburgh sample follow one of four physical aggression trajectories. See Figure 7. As in the other four samples, a group of boys in the Pittsburgh sample engage in little physically aggressive behavior. This group accounts for 36% of the sample. Another, smaller group (10%) comprises boys who engage in consistently high levels of physical aggression that increases over time. The remaining 55% of the boys fall into one of two groups. One group includes those boys (22%) who exhibit stable, moderately high levels of physical aggression over time. Boys in the second group exhibit low levels of physical aggression early on that increase over time.2

Figure 7.

Pittsburgh: Male trajectories of physical aggression. pred = predicted.

Finally, Figure 8 reports the results for the CDP sample (Nashville and Knoxville, Tennessee, and Bloomington, Indiana). Here a three-group model best fits the data. The largest group (64%) displays little physical aggression. Although this group’s trajectory does suggest rising physical aggression, this rise is insignificant and virtually undetectable. The next largest group (29%) displays a modest level of physical aggression that increases slightly from age 5 through age 11. This increase, however, is not significant. Finally, there is a small group, 7% of the sample, who display a high and rising rate of physical aggression. The size and the pattern of behavior of this group are virtually identical to those of the high-rate group identified in the Pittsburgh sample.

Although there are some obvious differences in the developmental models tracing boys’ physical aggression over time at each site, there are also some clear similarities. Consistent with results from the Montreal sample, at each of the other sites, a three- or four-group model best represents pathways of physical aggression “(see Table 1). Further, in every case, the model includes a trajectory representing a small group of boys—less than 10% of the sample—who engage in consistently high levels of physical aggression over age. Every site also has a group of boys of greatly varying size—between 15% and 60% of the population—who engage in almost no physical aggression over time. In fact, at all six sites, the modal trajectory is one that reflects a longitudinal pattern of either very little physical aggression or a low level of physical aggression over age.

Table 1.

Age Trends for Physical Aggression by Site and Sex

| Site | Maximum age (in years) | Total no. of groups | % in chronic group Boys | No. of declining groups | No. of stable groups | No. of increasing groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | ||||||

| Montreal | 15 | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||

| Quebec | 12 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 2 | |

| Christchurch | 13 | 3 | 11 | 3 | ||

| Dunedin | 13 | 3 | 9 | 3 | ||

| Pittsburgh | 10.5 | 4 | 10 | 2 | 2 | |

| CDP | 12 | 3 | 7 | 3 | ||

| | ||||||

| Girls | ||||||

| Quebec | 12 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 | |

| Christchurch | 13 | 3 | 10 | 3 | ||

| Dunedin | 13 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| CDP | 12 | 3 | 10 | 3 | ||

Note. CDP = Child Development Project (U.S.).

There is also a remarkable similarity in developmental trajectories within countries. In the male samples from Montreal and the province of Quebec, trajectories are stable or declining. The modal pattern is to start off being modestly aggressive at age 6 but to show a steady decline thereafter. In both New Zealand samples, all trajectories are stable, with the modal group displaying very little physical aggression, at least to their teachers. Only in the U.S. samples is there evidence of increasing physical aggression with age. In both the Pittsburgh and CDP samples, there is a group of boys—about 10% of the sample—with high and rising levels of physical aggression.

Although longitudinal patterns across sites exhibit evidence of both stability and change in absolute levels of physical aggression, all models indicate relative stability across levels of physical aggression. In none of the models do trajectories of physical aggression cross one another—suggesting that even if boys’ physically aggressive behavior changes over time, their comparative ranking within the population remains constant. Boys following a high and chronic physical aggression trajectory (even one that is declining) always rank higher on physical aggression than their counterparts in other groups, and boys following a low-level trajectory (whether stable, increasing, or decreasing) always rank between the never and chronic groups on physical aggression.

Thus, the models of physical aggression highlight rank stability coupled with evidence of both stability and change in absolute levels of physical aggression over time. However, even in models exhibiting evidence of absolute change in physical aggression over time, the trajectories reflect patterns of gradual change as opposed to sudden increases or decreases in these behaviors. Further, there is no evidence of late onset of physical aggression. Even in the Pittsburgh and CDP samples, where there is evidence of increasing physical aggression, these increases are gradual and continuous and do not emerge de novo during the period of observation. This supports the suggestion that the “onset” of physical aggression occurs during the preschool years, prior to the initial assessments in these data sets between ages 5 and 7 (Tremblay et al., 1999).

The findings based on mother ratings were substantially similar. In particular, the mother-based models revealed no evidence of late onset of physical aggression. As with teachers, our earliest mother assessment of physical aggression was at age 5.

Female physical aggression

For the Quebec, Dunedin, Christchurch, and CDP sites, comparable female samples were available. Similar analyses were conducted with these female samples, allowing for a comparison of developmental trajectories of problem behavior across sex. For physical aggression, trajectory models based on teacher reports suggest both similarities and differences in the longitudinal development of physical aggression for boys and girls.

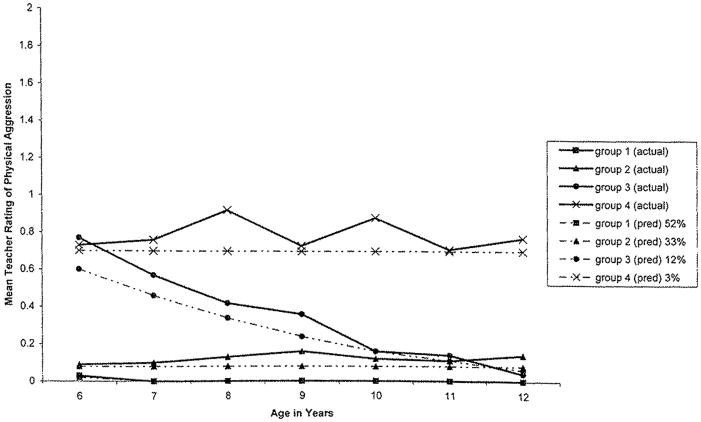

In the Quebec sample, a model based on teacher reports of girls’ physical aggression reveals four distinct trajectories (see Figure 9). There is a small group of girls (3%) who exhibit stable levels of chronic physical aggression over time. There is also a large group of girls (52%) who exhibit little physical aggression. The remaining 45% of the sample follow one of two trajectories. Thirty-three percent of the girls in the sample exhibit a longitudinal pattern that reflects a stable, low level of physical aggression. Another 12% follow a trajectory of rapid decline that begins at a “chronic” level and declines until age 12, when girls in this group exhibit almost no physical aggression.

Figure 9.

Quebec: Female trajectories of physical aggression. pred = predicted.

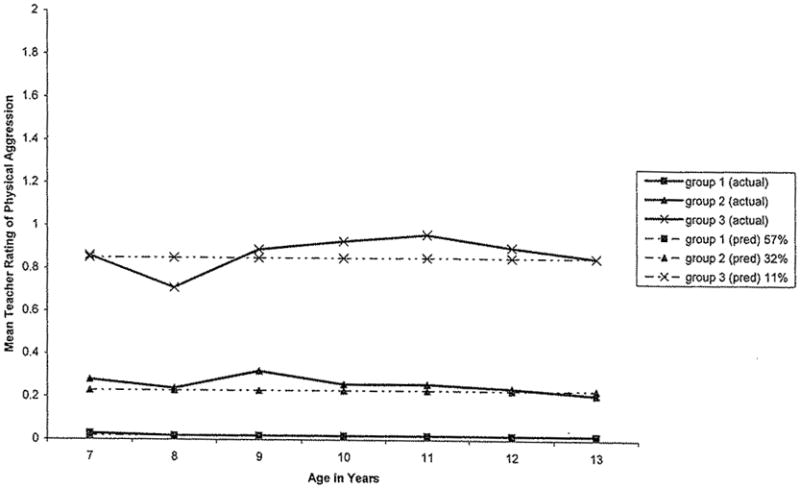

As shown in Figure 10, for the Christchurch sample, a three-group model best represents the longitudinal development of physical aggression for girls. A small group of girls (10%) follow a stable, chronic physical aggression trajectory. Most of the girls (48%) follow a stable, low-level trajectory of physical aggression over time. The remaining 42% of the girls are never physically aggressive across assessment periods.

Figure 10.

Christchurch: Female trajectories of physical aggression. pred = predicted.

The best-fitting trajectory model for the Dunedin sample suggests that these girls follow one of two developmental pathways for physical aggression (see Figure 11). The majority of this sample (57%) follow a stable trajectory of little physical aggression. The remaining 43% of the girls engage in a moderate level of physical aggression that declines gradually over time.

Figure 11.

Dunedin: Female trajectories of physical aggression. pred = predicted.

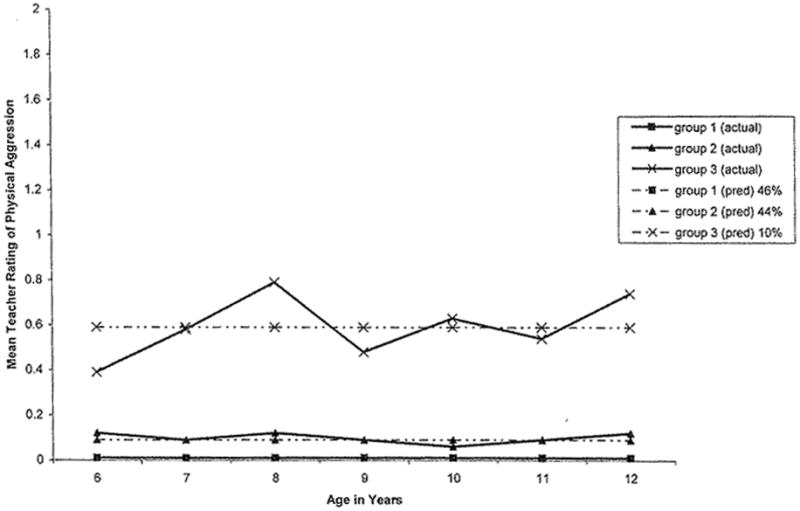

In the CDP sample, physical aggression for girls follows a three-group model in which all trajectories are stable (see Figure 12). The largest group of girls (46%) are rarely physically aggressive, whereas a small percentage (10%) display relatively high levels of stable physical aggression. The remaining 44% of the girls follow a path represented by consistent, low levels of physical aggression as they age. This model is almost identical to the model representing the development of physical aggression for girls in the Christchurch sample.

Figure 12.

Child Development Project: Female trajectories of physical aggression. pred = predicted.

In some ways, these four models are distinct from one another and from the models that trace the development of physical aggression in boys (see Table 1). The most notable distinction between the four models tracing girls’ physical aggression over time is the range in the ideal number of groups. The Christchurch and CDP samples have three distinct physical aggression trajectories, whereas the Quebec sample has four distinct trajectories and the Dunedin sample only two. Of the six models of male physical aggression, all have three or four groups. Comparatively, the four female models of physical aggression display a greater range of ideal groups. Also notable is that girls exhibit lower mean levels of physical aggression than do boys across all four sites with comparable data for boys and girls. Even among girls who exhibit chronic physical aggression across assessment periods, their mean levels of physical aggression are notably lower than those of chronic physically aggressive boys in the same sample. Nonetheless, at each site, mean ratings of physical aggression among chronically aggressive girls are higher than those for any of the nonchronic male groups.

Despite these differences, there are some patterns that both cut across the female models and mirror the male models. Even with the notable variation in number of groups across female models, in all cases, the majority of the girls are in the rare and low-level physically aggressive groups. Recall that the majority of boys at each site also fell into the rare and low-level physically aggressive categories. So, even though girls exhibit lower mean levels of physical aggression than boys do, little to no involvement in physical aggression is the modal pattern across sites and across sex. Also, as is the case among boys, chronic physical aggression is unusual for girls. The Quebec, Christchurch, and CDP female samples each have a small group of girls who follow a chronic physical aggression path (3%, 10%, and 14%, respectively), and in the Dunedin sample there are no girls who follow a chronic physical aggression trajectory.

Physical aggression trajectories for girls exhibit patterns of stability and decline and no evidence of increasing or late-onset physical aggression (see Table 1). Further, models of physical aggression for girls from the Christchurch, Dunedin, and CDP samples suggest rank stability consistent with that of the male models of physical aggression. Only in the trajectory model for the Quebec female sample (see Figure 9) is there any evidence of change in rank stability. In this model, there is one declining trajectory group that, at the outset, exhibits a higher mean level of physically aggressive behavior than the stable, chronic group and that, at final assessment, exhibits a mean level of physical aggression that is comparable to the behavior of the “nevers.” However, this group makes up only 12% of the sample, and the remaining 88% exhibit rank stability consistent with other models of both male and female physical aggression.

In sum, then, trajectory models of physical aggression for both boys and girls suggest that developmental pathways of physical aggression follow individual-level patterns of stability or decline coupled with a high degree of stability in relative position across individuals. Only in the U.S. samples did we find evidence of increasing physical aggression. Further, there is no evidence of sudden, late-onset physical aggression among boys or girls in any of the samples.

Trajectories of Physical Aggression and Later Delinquency

Analyses tracing the development of physical aggression in childhood serve to reinforce the proposition that aggregate-level analyses of changes in mean levels of physical aggression over time do not adequately capture between-individual differences in the developmental course of physical aggression. Across sites and sex, there is clear variation in childhood trajectories of physical aggression across individuals. We now move to an examination of the hypothesis that these distinct trajectories are differentially associated with the likelihood of engaging in adolescent delinquency. Nagin and Tremblay (1999) found that membership in a group exhibiting a chronic physical aggression trajectory throughout childhood increased the risk of later violence. Here we test the robustness of this finding across four additional data sets (self-reported delinquency data were not available for the Pittsburgh sample) and across sex by examining the linkage between trajectories of physical aggression and adolescent delinquency (both violent and nonviolent). We examine this relation both bivariately and with controls for potentially comorbid disruptive behaviors (opposition, hyperactivity, and, for those sites where the data are available, serious [nonphysically aggressive] conduct problems). For these regression models, delinquency scales comprise data collected after the final assessment of childhood disruptive behaviors used in the trajectory models, ensuring proper time ordering. These scales reflect delinquency at age 13 for the Quebec and CDP samples, at age 17 for the Montreal sample, and at age 18 for the Dunedin and Christchurch samples.

A summary of the results of the analysis linking the posterior probabilities of physical aggression group membership to violent and nonviolent delinquency is reported in Table 2. For boys, models assessing the bivariate relation between physical aggression in childhood and delinquency in adolescence indicate that a childhood marked by consistently high levels of physical aggression is associated with an increased likelihood of both violent and nonviolent delinquency in adolescence. For all five sites, childhood physical aggression is linked to later violent offending, suggesting a clear pattern of homotypic continuity from childhood into adolescence. Moreover, in all but one site (the CDP site), there is evidence of heterotypic continuity, with childhood physical aggression also exhibiting a significant link to nonviolent offending in adolescence (see Table 2). Thus, these findings based on trajectory analysis closely conform to existing evidence showing a strong correlation between childhood problem behavior and later delinquency for boys (e.g., Ensminger, Kellam, & Rubin, 1983; Farrington, 1995; Loeber, Farrington, Stouthamer-Loeber, Moffitt, & Caspi, 1998; Pulkkinen & Tremblay, 1992; Stattin & Magnusson, 1989). They also suggest that levels of childhood physical aggression may account for much of this relation.

Table 2.

Results of Bivariate Regression Models of Externalizing Behavior and Self-Reported Delinquency

| Type of delinquency | Physical aggression | Nonaggressive conduct problems | Opposition | Hyperactivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | ||||

| Violent | 5/5 | 3/3 | 5/5 | 4/5 |

| Nonviolent | 4/5 | 3/3 | 4/5 | 4/5 |

| Girls | ||||

| Violent | 3/4 | 1/2 | 3/4 | 2/4 |

| Nonviolent | 2/4 | 1/2 | 3/4 | 3/4 |

Note. For each cell, the numerator is the number of sites for which the relationship was significant, and the denominator is the number of sites for which the relationship was evaluated. See Appendix B for a list of the sites where the relationship was significant.

Despite similarities in the developmental trajectories of physical aggression for boys and girls, the linkage between childhood physical aggression and later offending is less consistent among girls (see Table 2). As is the case among boys, the results indicate a high degree of homotypic continuity in aggressive behavior from childhood into adolescence for girls. With the exception of the Dunedin sample, bivariate analyses indicated a significant association between childhood physical aggression trajectories and violent offending in adolescence among girls. Evidence that this relation extends to nonviolent offending among girls is minimal. Only in the CDP sample was there evidence of both homotypic and heterotypic continuity, with a significant bivariate relation between childhood physical aggression and both violent and nonviolent adolescent offending. This was not the case for the Quebec and Christchurch samples. And although there is no evidence of a link between physical aggression and violent offending among girls in the Dunedin sample, there is a significant linkage between childhood aggression and nonviolent offending. So, whereas all male samples showed evidence of homotypic continuity that in all but one case was accompanied by evidence of heterotypic continuity, the picture is more muddled among girls. In two cases, female samples exhibited only homotypic continuity; in one sample, they exhibited both homotypic and heterotypic continuity; and in the final sample, they exhibited only heterotypic continuity. In other words, the linkage between childhood patterns of physical aggression and later offending was less patterned among girls than among boys, varying across sites and across outcomes.

These bivariate results introduce two important questions. First, among boys, is the relation between childhood physical aggression and adolescent delinquency actually a function of the independent influence of early physical aggression? Or, alternatively, does it reflect the comorbidity between physical aggression and other disruptive childhood behaviors that may have similar or even stronger links to adolescent delinquency than physical aggression does? Second, among girls, might other disruptive childhood behaviors provide a more consistent linkage to adolescent offending than physical aggression does? We addressed these questions in a multivariate model that examined the influence of physical aggression, along with opposition, hyperactivity, and serious (but non-physically aggressive) conduct problems, on later violent and nonviolent offending. In essence, this approach allowed us to examine the influence of each disruptive behavior on violent and nonviolent delinquency while controlling for the influence of the other disruptive behaviors.

The results suggest that among boys, physical aggression does, in fact, have a significant and independent influence on violent and nonviolent offending even when we account for the potentially confounding influence of other disruptive behaviors (see Table 3). Physical aggression remained a significant predictor of both forms of delinquency in 4 of 5 sites—the exception being the Christchurch site. These models do suggest, however, that childhood physical aggression is not the only disruptive behavior to influence later offending. Although hyperactivity was not associated with later delinquency at any of the sites, conduct problems consistently exerted a significant effect on violent delinquency when other disruptive behaviors were controlled, and opposition had some influence on nonviolent delinquency when other disruptive behaviors were controlled, though this pattern was inconsistent. For boys, then, physical aggression appears to be a distinct risk factor for violent and nonviolent delinquency, conduct problems independently increase the risk of violent delinquency, and opposition, in limited instances, independently increases the risk of nonviolent delinquency.

Table 3.

Results of Multivariate Regression Models of Externalizing Behavior and Self-Reported Delinquency

| Type of delinquency | Physical aggression | Nonaggressive conduct problems | Opposition | Hyperactivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | ||||

| Violent | 4/5 | 2/3 | 1/5 | 0/5 |

| Nonviolent | 3/5 | 1/3 | 2/5 | 0/5 |

| Girls | ||||

| Violent | 1/4 | 0/2 | 0/4 | 0/4 |

| Nonviolent | 0/4 | 1/2 | 1/4 | 0/4 |

Note. For each cell, the numerator is the number of sites for which the relationship was significant, and the denominator is the number of sites for which the relationship was evaluated. See Appendix B for a list of the sites where the relationship was significant.

For girls, the results suggest that, in multivariate regression models, no particular type of disruptive behavior during the elementary school years exerts a consistent, unique influence on violent or nonviolent delinquency during adolescence (see Table 3). With one exception, none of the disruptive behaviors exerted a significant effect on self-reported violent delinquency when the other disruptive behaviors were controlled. That exception was the CDP sample, for whom physical aggression was a distinct predictor of later violent behavior when opposition and hyperactivity were controlled. Among girls in the Dunedin sample, conduct problems were significantly related to later nonviolent delinquency when physical aggression, opposition, and hyperactivity were controlled. For girls in the Christchurch sample, opposition exerted an independent effect on nonviolent delinquency when the other disruptive behaviors were controlled.

Despite similar developmental patterns across childhood physical aggression for boys and girls, the relation between physical aggression and later offending, although strong and consistent among boys, was inconsistent among girls. Moreover, with the exception of the Christchurch sample, the influence of potentially comorbid disruptive behaviors did not dampen the relation between physical aggression and offending among boys. Among girls, however, in all but one instance, the introduction of other disruptive behaviors into the models examining the linkage between physical aggression and later offending reduced to insignificance the limited bivariate relations between physical aggression and offending. Although chronic childhood physical aggression emerges as an important predictor of adolescent offending among boys, it does not appear to predict adolescent offending among girls with any consistency.

Discussion and Conclusions

In general, physical aggression from school entry to early adolescence is rare. However, among both boys and girls, a small group of children stand out as exhibiting notably more physically aggressive behavior than their peers throughout childhood. Moreover, patterns of physical aggression appear to be relatively stable, with some evidence of gradual increases or decreases over time but consistent rank stability across sites and sex. There is no evidence of the sudden and dramatic changes in disruptive behaviors implicated in typologies that, predict the onset of problem behavior in late childhood or during adolescence (e.g., Loeber & Hay, 1994; Moffitt, 1993; Patterson, DeBaryshe, & Ramsey, 1989). This may be due to the fact that most of the trajectory analyses included subjects who were not older than 13 years. However, the analyses with the Montreal sample included data on boys up to age 15 and did not show any indication of an adolescent-onset group. Instead, they showed a continuation of the desisting process among all but the chronic physical aggression group (see also Brame, Nagin & Tremblay, 2001).

Nonetheless, we recognize that these trajectory analyses, which end in early adolescence, may not reflect behavioral changes resulting from important developmental shifts in biological and contextual factors during the transitions into and out of adolescence. In particular, gains in physical size and strength accompanying puberty, coupled with reductions in parental and other adult supervision and increases in the amount and importance of peer interaction, could all trigger, in some adolescents, sudden increases in disruptive behaviors not captured in these analyses. A valuable next step would be to extend the current analysis to explore the developmental trajectories of physical aggression into young adulthood, taking into account potential developmental shifts in the manifestation of such behaviors over time.

Given evidence from trajectory analyses suggesting that across sites, there are small but identifiable numbers of both boys and girls who exhibit chronic physical aggression throughout childhood, we examined whether this chronic behavior pattern led to adolescent delinquency. Consistent with the results of Nagin and Tremblay (1999), our results suggest that physical aggression in childhood is a distinct predictor of later violent delinquency. Our findings also suggest that this relation extends to nonviolent offending as well. However, our results clearly indicate that these conclusions are reserved exclusively for boys, because no consistent relation emerged between childhood physical aggression and adolescent offending among girls.

The data for boys indicate that childhood physical aggression is the most consistent predictor of both violent and nonviolent offending in adolescence. However, there is also evidence to suggest that, independent of physical aggression, early nonaggressive conduct problems increase the risk of later violent delinquency and that early oppositional behaviors independently increase the risk of nonviolent delinquency. These findings suggest a model of the offending process in which the child’s generalized tendencies to engage in early disruptive behaviors influence later delinquency, with different patterns of early behavior problems being associated with differing delinquent outcomes. Nonetheless, the predictions made in the introduction were sustained to the extent that physical aggression is she most consistent predictor of delinquency. It is important to note that the analyses link early problem behavior to delinquency in both early and later adolescence because outcome variables were measured at age 13 at some sites and at ages 17 and 18 at other sites. The age at which outcomes are measured appears to have no impact on the relationship between early problem behavior and later delinquency, suggesting that this relationship is sustained throughout adolescence.

The influence of physical aggression, opposition, and nonphysically aggressive conduct problems on later delinquency is in contrast to the consistent finding that hyperactivity has no independent influence on adolescent delinquency. Despite claims that early hyperactivity is a risk factor for later delinquency (Campbell, Pierce, Moore, & Marakovitz, 1996; Taylor, Chadwick, Heptinstall, & Danckaerts, 1996), the present analyses do not support that conclusion. “When we controlled for the correlated effects of other disruptive behaviors, hyperactivity was not predictive of violent or nonviolent delinquency in any of the data sets. This finding is consistent with results from a growing number of studies suggesting that hyperactivity is not correlated with criminal outcomes once the influence of other conduct problems is taken into account (Farrington, Loeber, & VanKammen, 1990; Fergusson, Horwood, & Lynskey, 1993; Fergusson, Lynskey, & Horwood, 1996; Lahey, McBurnett, & Loeber, 2000; Lynskey & Fergusson, 1995). Hence, although it is possible that hyperactivity interacts with other disruptive behaviors in childhood to aggravate their influence on later offending, it does not appear to be an independent predictor of offending outcomes.

It is important here to note that the prediction analyses relied on trajectories of teacher-rated behavior problems that were based on seven time points (except for the Dunedin site, where trajectories were based on four time points) beginning at ages 5–6 and extending to age 10½ or later (up to age 15 in Montreal). These trajectories were then used to predict self-reported delinquency at a later point in time during adolescence. The main value of these results is in showing that there is continuity in problem behavior from childhood to adolescence across informants and that there is a specific continuity for physical aggression. Although there is much comorbidity among the disruptive behaviors, chronic physical aggression during the elementary school years (and in some cases chronic nonphysically aggressive conduct problems) specifically increases the risk for continued physical violence during adolescence, whereas chronic oppositions) behavior and hyperactivity during the elementary school years do not independently increase this risk.

It cannot be concluded from these results that hypotheses concerning the role of hyperactivity and opposition in the development of physically violent delinquency are disconfirmed (Loeber & Hay, 1994; Moffitt, 1990, 1993). It is clear that children are already at, or close to, their peak levels of disruptive behavior, including physical aggression, when they enter school. It is also clear that those who display the chronic trajectory of physical aggression, along with those who display chronic conduct problems, are more at risk for violent juvenile delinquency than are those who display the chronic trajectories of hyperactivity or opposition. But, the influence of hyperactivity and opposition on physical aggression may be operating before school entry. We clearly need to study the preschool years to understand the extent to which each of these disruptive problems has an impact on the others. Because the available data indicate that physical aggression increases dramatically during the 2nd year after birth {Tremblay et al., 1999; Tremblay, Masse, Pagani, & Vitaro, 1996), the search for the mutual influences of the disruptive behaviors will need to start with the 1st year of life.

For practitioners, the results of these predictive analyses confirm that when the aim is to prevent physical violence and when resources are limited, children with chronic physical aggression and/or serious conduct problems should be the primary targets of intervention. However, we are not suggesting that practitioners wait until age 12 or 13 for confirmation of a chronic trajectory of physical aggression or serious conduct problems to offer a prevention program. One of the important findings of these analyses is that the chronic cases were generally at their highest levels of disruptive behavior when they entered kindergarten. Some desist and others do not. The next decade of research in this area should aim to identify preschool predictors of those who will not desist. Thus, instead of using trajectories of behavior problems during elementary school to predict undesirable behaviors at one or two points in time during adolescence, we need to find a set of early predictors that are relatively economical to obtain and that give accurate predictions of problem behavior trajectories spanning long periods of time, such as from childhood to adolescence or even from childhood to adulthood. Because the trajectories indicate much intraindividual stability in behavior problems over time, one would expect the prediction of trajectories to be much more accurate than the prediction of behavior at one or two points in time.

The prediction results for girls confirmed that girls’ involvement in juvenile delinquency is extremely difficult to predict (Tremblay et al., 1992; Zoccolillo, 1993). These null findings are impressive because they were replicated in four distinct samples. They appear to reflect the fact that in each of these samples, there is limited variation in the dependent variable (delinquency) for girls. As such, the null findings are a reflection of the fact that the variation in female delinquency as measured in these samples is so small that there is little to predict. Mean levels of both violent and nonviolent delinquency were smaller in each of the female samples than in the corresponding male samples. In essence, then, childhood physical aggression does not predict later delinquency for girls because girls are significantly less likely than boys to engage in the delinquent activities measured in these studies. It is precisely this lack of variation in delinquent outcomes in female samples that researchers commonly use to justify the exclusion of girls from research on the etiology of delinquency. However, given the notable similarities between trajectories representing the development of physical aggression across male and female samples, differences across sex both in mean levels of adolescent delinquency and in the linkage between these physical aggression trajectories and later delinquency remain a puzzle. The conclusion that female delinquency cannot be predicted because of low power misses the point. The interesting question is why female delinquency is so low despite similarities across sex in the development of physical aggression during childhood. Like boys, most girls exhibit little to no physical aggression in childhood and, for the female samples in each site except Dunedin, there is a discernible group of girls with chronic physical aggression throughout childhood. It is important to remember here that even though girls in all trajectory groups showed lower mean levels of physical aggression than their male counterparts, chronically aggressive girls exhibited higher mean rates of aggression than the bulk of their male counterparts. Their aggression levels were higher than those of all boys not in the chronically aggressive group. Hence, that the linkage between trajectories of childhood physical aggression and later delinquent outcomes is notably more consistent among boys suggests that there may be fundamental differences in the etiology of delinquency across sex (Rutter et al., 1998; Zoccolillo, 1993). A useful next step would be to focus on the magnitude of these relations across sex and formally test for sex differences.

These results clearly point to the need for more research exploring the adolescent manifestations of childhood physical aggression among girls. That girls exhibiting chronic physical aggression in childhood do not appear to be at the same risk for later delinquency as boys may indicate that protective factors shield such girls from the negative outcomes experienced by boys with similar behavior trajectories in childhood. As such, future research should explore the factors that inhibit delinquency among girls exhibiting chronically disruptive behavior in childhood. Research should also examine the possibility that these girls simply develop distinct problems in adolescence. The socialization patterns and interpersonal networks of female adolescents may work to inhibit delinquency among girls with a history of disruptive behavior but may foster other deviant outcomes more consistent with the female role such as alcohol or drug abuse, disordered eating, depression, or early pregnancy.

This study was designed to assess the hypothesis that physical aggression in childhood is a distinct predictor of adolescent delinquency—in particular, violent delinquency. As such, the analyses reported here explored the independent influence of various disruptive behaviors on violent and nonviolent delinquent outcomes and assessed their independent influences on these outcomes. Although the analyses were not intended as a test of specialization hypotheses, they do suggest a certain degree of specialization, indicating that physical aggression and nonaggressive conduct problems in childhood are more consistently related to later violent delinquency than are opposition or hyperactivity. Nonetheless, these findings do not preclude the possibility that children who display a variety of problem behaviors in childhood are most at risk for later delinquency. It may be, for example, that children who exhibit multiple chronic behaviors in childhood (including physical aggression) are at greater risk for later delinquency than are children exhibiting only chronic physical aggression. Future research should explore this possibility, ideally across multiple sites (see Pulkkinen & Tremblay, 1992).

The present research offers a unique picture of the relationship between childhood physical aggression and adolescent delinquency across multiple sites. Both consistencies and inconsistencies in cross-site results generated our conclusions. The way in which findings are shaped by similarities as well as differences across sites serves to illustrate the unique benefits of cross-site analysis. Although the value of cross-site analysis and robustness testing to the scientific process is widely recognized, researchers rarely attempt cross-site evaluations of central theoretical and empirical questions. The reasons for this are not difficult to fathom—cross-site research is difficult to coordinate and often generates inconsistent findings that are difficult to interpret. Nonetheless, single-site analyses are always vulnerable to the criticism that the results may be sample specific or a reflection of unspecific sample biases. Multiple-site analyses, although not definitive, guard against this criticism. Given the importance of robustness testing to the scientific process, multisite analyses are a strategic way to hasten the advancement of the discipline. The current study indicates that, though difficult, cross-site analyses are possible and that the results are fruitful. As such, we encourage increased efforts to develop cross-site communication and cooperation with the aim of generating more multiple-site studies. This is especially crucial as new longitudinal data collection efforts get under way. Communication and foresight in the early stages of data collection can ensure comparable sampling strategies and measures to facilitate future cross-site research collaborations.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was supported by the U.S. National Consortium on Violence Research. The data from the Dunedin Study were funded by the New Zealand Health Research Council and the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; Grants MH45070, MH49414, and MH56344). The data from the two Canadian studies were funded by Fonds pour la Formation de Chercheurs et l’Aide a la Recherche, the Conseil Québécois de la Recherche Sociale, the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec, the National Health Research Development Program of Canada, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the Molson Foundation, and the Canadian Institute of Advanced Research. Data from the Child Development Project study were funded by NIMH Grants MH 42498 and MH 57095 and by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant HD30572.

Appendix A Measures and Descriptive Statistics

Table A1.

Disruptive Behavior Scales Items for Each Site

| Site | Physical aggression | Opposition | Hyperactivity | Conduct problems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quebec | 3 items: fights with others; bullies/intimidates others; kicks/bites/hits others | 5 items: doesn’t share; irritable; disobedient; blames others; inconsiderate | 2 items: doesn’t sit still; squirmy/fidgety | 3 items: absent from school without permission (truant); steals; tells lies |

| Montreal | 3 items: fights with others; bullies/intimidates others; kicks/bites/hits others | 5 items: doesn’t share; irritable; disobedient; blames others; inconsiderate | 2 items: doesn’t sit still; squirmy/fidgety | 3 items: absent from school without permission (truant); steals; tells lies |

| Christchurch | 3 items: frequently fights with other children; bullies other children; temper outbursts | 6 items: irritable; often disobedient; defiant; impudent; stubborn; uncooperative | 7 items: squirming/fidgety; hardly ever still; restless/overactive; excitable/impulsive; short attention span; inattentive/easily distracted; poor concentration | Not available |

| Dunedin | 2 items: frequently fights with others; bullies other children | 3 items: irritable/quick to fly off the handle; often disobedient; often tells lies | 2 items: often running or jumping up and down/hardly ever still; squirmy/fidgety | 4 items: truant from school; stolen things on one or more occasions; often destroys own or others’ belongings; absent from school for trivial reasons |

| Child Development Project | 4 items: cruelty/bullying/meanness to others; fights with others; physically attacks people; threatens people | 4 items: argues a lot; defiant/talks back to staff; disobedient at school; disrupts class discipline | 5 items: can’t sit still/restless/hyperactive; impulsive/acts without thinking; can’t concentrate or pay attention for long; fails to finish things; fidgets | Not available |

| Pittsburgh | 5 items: cruelty/bullying/meanness to others; fights with others; threatens people; hits or physically fights with other students; starts a physical fight over nothing | 4 items: argues a lot; defiant/talks back to staff; disobedient at school; stubborn/sullen/irritable | 3 items: can’t concentrate or pay attention for long; can’t sit still/restless/hyperactive; fidgets | 4 items: destroys own things; destroys property belonging to others; lies or cheats; steals |

Table A2.

Violent and Nonviolent Delinquency Scales Items for Each Site

| Site | Violent delinquency | Nonviolent delinquency |

|---|---|---|

| Quebec | 7 items: used threat or force to get someone to do something; gang fighting; fist fighting; fighting with weapons; beating someone up for no reason; throwing things at people; carrying a weapon | 11 items: taking something worth $10 or more from school; shoplifting; entering a place without paying; taking money from home that is not yours; taking something worth less than $10; taking something worth between $10 and $100; taking something worth $100 or more; stealing a bicycle; knowingly buying stolen property; breaking and entering; breaking into someplace to steal something |

| Montreal | 7 items: used threat or force to get someone to do something; gang fighting; fist fighting; fighting with weapons; beating someone up for no reason; throwing things at people; carrying a weapon | 11 items: taking something worth $10 or more from school; shoplifting; entering a place without paying; taking money from home that is not yours; taking something worth less than $10; taking something worth between $10 and $100; taking something worth $100 or more; stealing a bicycle; knowingly buying stolen property; breaking and entering; breaking into someplace to steal something |

| Christchurch | 8 items: used threat or force to rob someone; gang fighting; attacked someone living in your home with a weapon; hit someone living in your home; attacked someone not living in your home with a weapon; hit someone with the intention of hurting them; carrying a hidden weapon; cruel to animals | 14 items: breaking and entering; taking something worth less than $5; taking something worth between $5 and $50; taking something worth between $50 and $100; taking something worth over $100; shoplifting; snatching purse/wallet or picking someone’s pocket; taking something from a car; buying or holding stolen goods; stealing a motor vehicle; damaging or destroying property; fire setting; using stolen checks or bank card; stealing money from workplace |

| Dunedin | 5 items: hit someone in anger; attacked with weapon; hit someone with intent to hurt; strongarm; gang fight | 23 items: run away; carried weapon; unruly in public; damaged property; broken in; stolen something worth less than $5; stolen something worth between $5 and $50; stolen something worth between $50 and $100; stolen something worth more than $100; shoplifting; snatched purse; stolen from a car; bought or sold stolen goods; joyriding; stolen a vehicle; passed bad checks; credit card fraud; cheat someone; driving offense; sold marijuana; sold hard drugs; used marijuana; used hard drugs |

| Child Development Project | 2 items: fights; attacks people | 4 items: steals at home; steals elsewhere; destroys others’ belongings; sets fires |

Table A3.

Quebec Sample: Descriptive Statistics for Disruptive Behavior Scales

| Aggression |

Opposition |

Hyperactivity |

Conduct problems |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | M | SD | α | M | SD | α | M | SD | α | M | SD | α |

| Boys | ||||||||||||

| 6 | .28 | .45 | .82 | .37 | .46 | .84 | .60 | .70 | .88 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 7 | .30 | .52 | .88 | .34 | .45 | .83 | .53 | .70 | .89 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 8 | .26 | .45 | .83 | .32 | .40 | .79 | .45 | .64 | .86 | .14 | .25 | .39 |

| 9 | .31 | .47 | .83 | .40 | .45 | .79 | .44 | .63 | .89 | .15 | .27 | .52 |

| 10 | .24 | .43 | .83 | .36 | .44 | .81 | .42 | .62 | .87 | .14 | .24 | .36 |

| 11 | .22 | .40 | .81 | .32 | .41 | .80 | .37 | .58 | .87 | .13 | .23 | .31 |

| 12 | .22 | .39 | .81 | .32 | .40 | .79 | .34 | .58 | .86 | .11 | .22 | .33 |

| Girls | ||||||||||||

| 6 | .08 | .25 | .80 | .19 | .32 | .78 | .30 | .54 | .89 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 7 | .08 | .26 | .87 | .20 | .33 | .79 | .28 | .53 | .86 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 8 | .07 | .24 | .80 | .19 | .33 | .79 | .22 | .48 | .86 | .09 | .21 | .48 |

| 9 | .06 | .22 | .78 | .19 | .32 | .78 | .21 | .43 | .85 | .08 | .19 | .32 |

| 10 | .05 | .17 | .67 | .16 | .30 | .78 | .16 | .39 | .82 | .08 | .19 | .32 |

| 11 | .04 | .18 | .79 | .15 | .28 | .74 | .12 | .34 | .75 | .06 | .17 | .33 |