Abstract

Interleukin-12 (IL-12) has been shown to enhance cellular immunity in vitro and in vivo. The beneficial roles of IL-12 as a DNA vaccine adjuvant have been commonly observed. Here the impact of IL-12 complementary DNA (cDNA) as an adjuvant for a human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 E7 DNA vaccine is investigated in a mouse tumour model. Coinjection of E7 DNA vaccine with IL-12 cDNA completely suppressed antigen-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) responses, leading to a complete loss of antitumour protection from a tumour cell challenge. In addition, antigen-specific antibody and T helper cell proliferative responses were also suppressed by IL-12 cDNA coinjection. This inhibition was observed over different IL-12 cDNA doses. Furthermore, separate leg injections of IL-12 and E7 cDNAs suppressed antigen-specific CTL and tumour protective responses, but not antibody and T helper cell proliferative responses, suggesting different pathways for suppression of these two separate responses. Further knockout animal studies demonstrated that interferon-γ and nitric oxide are not directly associated with suppression of antigen-specific antibody responses by IL-12 cDNA coinjection. However, nitric oxide was found to be involved in suppression of antigen-specific CTL and tumour protective responses by IL-12 cDNA coinjection. These data suggest that coinjection of IL-12 cDNA results in suppression of E7-specific CTL responses through nitric oxide, leading to a loss of antitumour resistance in this DNA vaccine model. This study further shows that the adjuvant effect of IL-12 is dependent on the antigen types tested.

Keywords: cervical cancer, DNA vaccines, human papillomavirus, immune suppression, interferon-γ, interleukin-12, nitric oxide

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 infection is a major cause of cervical cancer worldwide.1 The expression of HPV oncogenic proteins E6 and E7 is required for tumorigenesis and maintenance of the tumour state.2–4 Therefore, E6 and E7 proteins, which are unique to HPV-associated cervical cancer and its precursor disease, have been a major target for cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL)-mediated immunotherapy. To date, combined therapeutic approaches as well as numerous vaccine modalities, including E6-targeted or E7-targeted peptide/protein vaccines, dendritic cell vaccines, viral/bacterial vector delivery of vaccines and DNA vaccines, have been tested pre-clinically or in clinics (reviewed in refs 5, 6). In DNA vaccine approaches, Dr Wu and his groups have shown that coinjection of E7 DNA vaccine with plasmid DNAs coding for anti-apoptotic proteins or serine protease inhibitor can lead to augmentation of antigen-specific CTL and antitumour resistance.7,8 Our groups also reported that the antitumour efficacy of E7 DNA vaccine can be enhanced by altering the location of antigen expression (soluble, transmembrane, intracellular and lysosomal) and by optimizing antigen codon sequences.9 In these studies, CTL responses were responsible for tumour resistance. In our recent report, however, the antitumour efficacy of E7 DNA vaccine is far below that of E7 subunit vaccine,10 which further increases the need to improve the E7 DNA vaccine.

Among cytokines tested as a molecular adjuvant, interleukin-12 (IL-12) was the most effective for augmenting antigen-specific cellular responses in other vaccine model systems.11–13 In particular, coinjection with IL-12 complementary DNA (cDNA) resulted in the enhancement of antigen-specific CTL responses with inhibitory effects on humoral responses in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) DNA vaccine models.13 Iwasaki et al.14 also reported that IL-12 cDNA codelivery with a DNA immunogen encoding influenza nucleoprotein (NP) augments cellular responses including CTL responses. Direct administration of IL-12 proteins can also affect tumour progression and metastasis in animal tumour models.15,16 Interleukin-12 is a heterodimeric cytokine consisting of two chains, p35 and p40. It is mainly produced by activated antigen-presenting cells including macrophages, dendritic cells and B cells.17,18 Interleukin-12 induces T helper type 1 (Th1) type immune responses through inducing the maturation of type 1 Th cells from the uncommitted T-cell pool and promotes natural killer (NK) activity and CTL maturation.19 Furthermore, IL-12 induces interferon-γ (IFN-γ) production by NK cells.18 Based upon these previous findings, it is highly likely that coinjection of E7 DNA vaccine with IL-12 cDNA as an adjuvant induces a dramatic increase in antigen-specific CTL and tumour protective responses. Furthermore, no effects of IL-12 cDNA on antigen-specific immune responses and antitumour resistance have been reported in an E7 DNA vaccine model.

In this study, we observed that IL-12 cDNA coinjection suppresses E7-specific CTL and tumour protective responses, as well as antibody and Th cell proliferative responses. In particular, separate leg injections of IL-12 and E7 cDNAs resulted in suppression of antigen-specific CTL and tumour protective responses, but not antibody and Th cell proliferative responses. Further knockout animal studies showed that IFN-γ and nitric oxide are not associated with suppression of E7-specific antibody responses. However, nitric oxide was found to be associated with suppression of antigen-specific CTL responses by IL-12 cDNA coinjection. These data suggest that IL-12 suppresses E7-specific CTL responses by nitric oxide, leading to a loss of antitumour protective immunity in this DNA vaccine model.

Materials and methods

Animals

Female C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Daehan Biolink (Chungbuk, Korea). C57BL/6 IFN-γ knockout (KO) mice were donated by Dr Young Chul Sung (POSTECH, Korea). C57BL/6 NOS2 KO mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Their care was performed under the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocols.

DNA and immunization of mice

The tibialis muscles of 4- to 6-week-old mice were injected with 50 μg E7 DNA vaccines (pcDNA3-Sig/sE7/LAMP, pE7)9 in a final volume of 100 μl of 0·25% bupivacaine-containing phosphate buffered saline (PBS) using a 28-gauge needle (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Unless otherwise noted, animals were immunized intramuscularly (i.m.) with 50 μg pE7 and 50 μg pIL-12 at 0, 2 and 4 weeks. pcDNA3 was used as a negative control. At 6 weeks, the animals were used for either immune assays or tumour protection study. For IL-12 cDNA dose assay, 10 μg (5 μg IL-12 p40 + 5 μg IL-12 p35), 30 μg (15 μg IL-12 p40 + 15 μg IL-12 p35) or 50 μg (25 μg IL-12 p40 + 25 μg IL-12 p35) of pcDNA3-IL-12 (pIL-12)11,12 was mixed with pE7 solution before injection. For separate leg muscle injections, each leg was immunized with 50 μg of the plasmids in 100 μl of 0·25% bupivacaine-containing PBS. Plasmid DNA was produced in bacteria and purified by endotoxin-free Qiagen kits according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect antibodies against E7 protein was performed as previously described.20–22 In particular, recombinant E7 protein20 (1 μg/ml in PBS) was used as a coating antigen.

Th cell proliferative responses

Spleens were aseptically removed from each group and pooled together. Lymphocytes were harvested from spleens and prepared as the effector cells by removing the erythrocytes and by washing several times with cRPMI (RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1%l-glutamine). The isolated cell suspensions were resuspended to a concentration of 6 × 106 cells/ml. A 50-μl aliquot containing 3 × 105 cells was immediately added to each well of a 96-well microtitre flat-bottom plate. The HPV 16 E7 protein at final concentrations of 5 or 10 μg/ml was added to wells in triplicate. The cells were incubated at 37° in 5% CO2 for 2 days; 10 μl 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) was added to each well and the cells were incubated for 12–18 hr at 37°. The amount of incorporated BrdU was measured by colorimetric immunoassay in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol (Roche, Germany) and optical density (OD) values were obtained. To ensure that cells were healthy, 5 μg/ml concanavalin A (Sigma, St Louis, MO) was used as a polyclonal stimulator positive control.

CTL assay

The CTL assays were performed as previously described.10,23 In brief, splenocytes were cultured in cRPMI supplemented with 1 mm sodium pyruvate and 5·5 × 10−5 mβ-mercaptoethanol, and stimulated in vitro for 5 days with 1 μg/ml E7 peptides [containing the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I epitope at amino acids 49–57]24 and 25 units/ml recombinant IL-2 (BD, Mountain View, CA). After background subtraction, the per cent lysis was calculated by 100 × [(experimental release – effector spontaneous release – target effector spontaneous release) / (target maximum release – target spontaneous release)].

IFN-γ assay

A 1-ml aliquot containing 6 × 106 splenocytes was added to the wells of 24-well plates. Then, cells were stimulated with 1 μg/ml E7 peptides (containing the MHC class I epitope at amino acids 49–57).24 The E7 CTL peptide (RAHYNIVTF) was purchased from Peptron, Taejon, Korea. After 3 days incubation at 37° in 5% CO2, cell supernatants were secured and then used to detect levels of IFN-γ using commercial cytokine kits (Biosource International, Camarillo, CA) by adding the extracellular fluids to the IFN-γ-specific ELISA plates.

Tumour protection assay

The 3 × 104 TC-1 cells were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) into the mid flank of C57BL/6 mice for antitumour protection studies. The TC-1 tumour cells (a kind gift from T.-C. Wu, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD) were grown in cRPMI supplemented with 400 μg/ml G418. The tumour cells were washed twice with PBS and injected into mice. Mice were monitored twice per week for tumour growth. Tumour growth was measured in mm using a calliper, and was recorded as mean diameter [longest surface length (a) and width (b), (a + b)/2]. Mice were killed when tumour size reached more than 2 cm in mean diameter.

Sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) and Western blot assay

Rhabdomyosarcoma cells (5 × 105 cells) grown in 60-mm dish plates were transfected with plasmid DNAs using jetPEI™ DNA transfection reagents according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Polyplus-transfection Inc., New York, NY). One day post-transfection, cells were collected in 100 μl of lysis buffer [0·1 m Tris–HCl (pH 7·8), 0·5% Triton X-100, protease inhibitor cocktail]. Proteins were analysed by 12% SDS–PAGE and then electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ). The membrane was pre-equilibrated with TBST solution [10 mm Tris–HCl (pH 8·0), 150 mm NaCl, 0·1% Tween-20] containing 2% bovine serum albumin for 1 hr and then reacted with anti-HPV 16 E7 monoclonal antibodies (Oncogene, Boston, MA). After three washes with TBST, the membrane was incubated with anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG)-horseradish peroxidase (Sigma) for 1 hr at room temperature. The immunoreactive protein bands were visualized using the enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagents (Amersham). In particular, anti-β-actin antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Tech., Danvers, MA and used as primary control antibodies.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by the independent-samples t-test or chi-squared test using the spss 13.0 software program (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Values of experimental groups were compared with the values of the control group. The P values < 0·05 were considered significant.

Results

Effects of IL-12 cDNA on E7-specific CTL and IFN-γ responses, and antitumour protective immunity

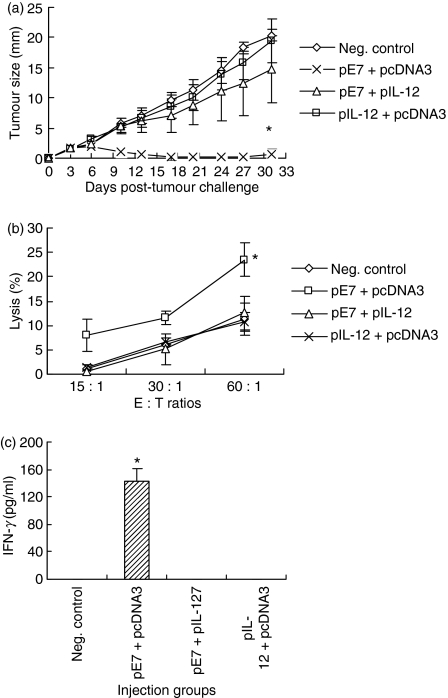

The E7-specific CD8+ CTL play a major role in protection from an E7-expressing TC-1 tumour cell challenge.9,10,20,25–27 To determine whether coinjection of E7 DNA vaccine with IL-12 cDNA augments antitumour protective immunity from a TC-1 cell challenge, mice were coimmunized i.m. with 50 μg E7 DNA vaccine (pE7) and 50 μg IL-12 cDNA (pIL-12), followed by a tumour cell challenge. As shown in Fig. 1(a), animals immunized with pE7 alone showed almost complete protection from TC-1 tumour challenge. However, animals immunized with pE7 plus pIL-12 displayed a complete loss of antitumour resistance in a manner similar to control groups. We next tested levels of antigen-specific CTL and IFN-γ responses. As shown in Fig. 1(b,c), E7-specific CTL lytic activity was induced significantly by pE7 alone (Fig. 1b). However, when animals were coinjected with pE7 plus pIL-12, E7-specific CTL lytic activity was completely inhibited to the level in negative controls showing a background activity. When splenocytes of animals immunized with pE7 alone were stimulated in vitro with E7 CTL peptides, antigen-specific IFN-γ production was induced to a significant level (Fig. 1c). However, when splenocytes of animals coimmunized with pE7 + pIL-12 were stimulated in vitro with E7 CTL peptides, antigen-specific IFN-γ production was inhibited to a background level. This complete suppression in both in vitro CTL activity and IFN-γ production matches well with a complete loss of antitumour protection from a tumour cell challenge. These data suggest that IL-12 delivered in a DNA form completely inhibits antigen-specific CTL responses, thereby giving no antitumour protection in an HPV 16 E7 DNA vaccine model.

Figure 1.

Effect of interleukin-12 (IL-12) complementary DNA coinjection on antitumour resistance (a), E7-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) activity (b) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) production (c). (a) Each group of animals (n = 5) was immunized intramuscularly with 50 μg pE7 and 50 μg pIL-12 at 0, 2 and 4 weeks. pcDNA3 was used as a negative control. At 6 weeks, the animals were challenged subcutaneously with 3 × 104 TC-1 tumour cells per mouse and then tumour sizes were measured over time. (b, c) Each group of animals (n = 5) was immunized as above. At 6 weeks, animals were killed to obtain splenocytes, which were tested for CTL lytic activity (b) and IFN-γ production (c) as shown in the Materials and methods section. Samples were assayed in triplicate. Values represent means of tumour sizes, % lysis and released IFN-γ concentrations, and the SD, respectively. *Statistically significant at P < 0·05 using the independent-samples t-test compared with negative control.

Effects of IL-12 cDNA coinjection on E7-specific antibody and Th cell proliferative responses

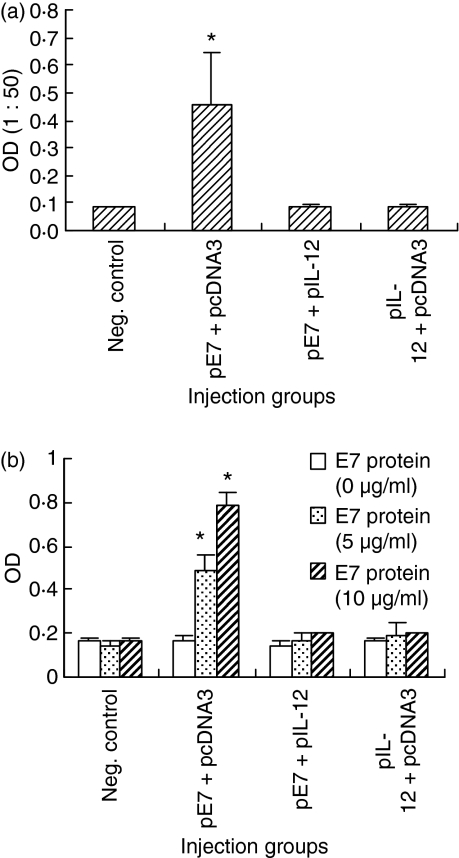

We were next interested in evaluating whether coinjection of E7 DNA vaccine with IL-12 cDNA also influences antigen-specific antibody responses. For this, mice were coimmunized with 50 μg pE7 and 50 μg pIL-12, and then sera were obtained at 6 weeks following the first DNA inoculation for ELISA. As shown in Fig. 2(a), E7-specific antibody levels were induced significantly by E7 DNA vaccine (pE7) alone. However, when pE7 was coinjected with pIL-12, antigen-specific antibody levels were completely inhibited to those of negative controls. We also tested antigen-specific Th cell proliferative responses. Splenocytes of animals coinjected with pE7 and pIL-12 were stimulated in vitro with E7 proteins for BrdU incorporation assay. As shown in Fig. 2(b), antigen-specific Th cell proliferative responses were induced to a significant level when animals were immunized with pE7 alone. However, Th cell proliferative responses were completely inhibited when animals were coinjected with pE7 + pIL-12. Throughout this study pcDNA3 has been routinely used as a negative control and has had no effect on E7-specific IgG and Th cell proliferative responses. These data suggest that IL-12 delivered in a DNA form can also inhibit antigen-specific antibody and Th cell proliferative responses in an HPV 16 E7 DNA vaccine model.

Figure 2.

Effect of interleukin12 (IL-12) complementary DNA coinjection on E7-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) (a) and T helper (Th) cell proliferative (b) responses. (a) Each group of animals (n = 5) was immunized intramuscularly with 50 μg pE7 and 50 μg pIL-12 at 0, 2 and 4 weeks. pcDNA3 was used as a negative control. At 6 weeks, mice were bled and then each serum per group was diluted to 1 : 50 for reaction with E7 in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. (b) The above animals were killed to obtain splenocytes. The pooled splenocytes were tested for Th cell proliferation responses as shown in the Materials and methods section. Samples were assayed in triplicate. Values and bars represent means of optical density (OD) values and the SD, respectively. These experiments were repeated with similar results. *Statistically significant at P< 0·05 using the independent-samples t-test compared to negative control.

Effects of IL-12 cDNA doses on E7-specific humoral and cellular responses, and antitumour protection

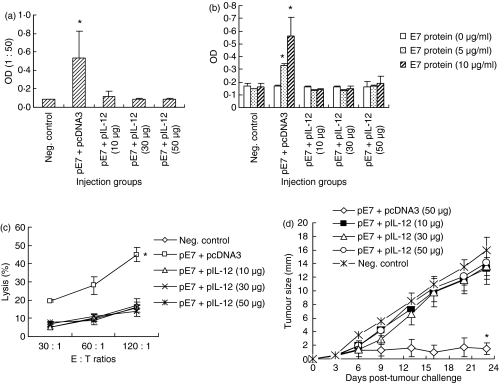

To test the dose effect of IL-12 cDNA on immune suppression and antitumour protection from a tumour cell challenge, animals were immunized with E7 DNA vaccine with different doses of IL-12 cDNA. As shown in Fig. 3(a–c) all animal groups immunized with pE7 (50 μg) + pIL-12 (10 μg), pE7 (50 μg) + pIL-12 (30 μg) and pE7 (50 μg) + pIL-12 (50 μg) displayed a complete loss of antigen-specific antibody (Fig. 3a) and Th cell proliferative responses (Fig. 3b) and CTL lytic activity (Fig. 3c) in a manner similar to those of control animal groups. Antitumour resistance against TC-1 tumour cells was also lost in all these animal groups coinjected with pIL-12 in a dose range from 10 to 50 μg (Fig. 3d). These data suggest that antigen-specific humoral and cellular responses, as well as antitumour resistance can be suppressed even at an E7 to IL-12 cDNA dose ratio of 5 to 1.

Figure 3.

Effects of interleukin-12 (IL-12) complementary DNA doses on E7-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) (a), T helper (Th) cell proliferative (b), cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) (c) responses, and antitumour protection (d). (a) Each group of animals (n = 5) was immunized intramuscularly with pE7 (50 μg), and pIL-12 (10, 30 and 50 μg) at 0, 2 and 4 weeks. pcDNA3 was used as a negative control. At 6 weeks, mice were bled and each serum per group was diluted to 1 : 50 for reaction with E7 in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. (b, c) The above animals were killed to obtain splenocytes, which were tested for Th cell proliferative responses (b) and CTL lytic activity (c) as shown in the Materials and methods section. Samples were assayed in triplicate. (d) Each group of animals (n = 5) was immunized as above. At 6 weeks, animals were challenged subcutaneously with 3 × 104 TC-1 cells per mouse and then tumour sizes were measured over time. Values and bars represent means of OD values, % lysis and tumour sizes, and the SD, respectively. These experiments were repeated with similar results. *Statistically significant at P < 0·05 using the independent-samples t-test compared to negative control.

Effects of IL-12 cDNA delivered separately from E7 DNA vaccine on induction of antigen-specific IgG, Th cell proliferative and CTL responses as well as antitumour resistance

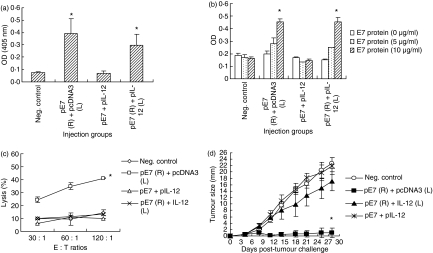

To determine whether separate injections of E7 DNA vaccine from IL-12 cDNA might influence antigen-specific antibody, Th cell proliferative, and CTL responses, as well as antitumour protection against TC-1 tumour cells, animals were immunized i.m. with pE7 (50 μg) on the right (R) leg and with pIL-12 (50 μg) on the left (L) leg. As shown in Fig. 4(a,b), animal groups coimmunized with pE7 separately from pIL-12 showed induction of antigen-specific antibody and Th cell proliferative responses in a manner similar to those immunized with pE7 alone. In contrast, animal groups immunized with pE7 + pIL-12 on the same leg failed to induce antigen-specific IgG and Th cell proliferative responses as we previously observed (Fig. 2). These data suggest that the observed immune suppression in both antibody and Th cell proliferative responses requires the local coexpression of E7 antigens plus IL-12. Figure 4(c,d) shows antigen-specific CTL responses and antitumour protection patterns by separate injections of pE7 and pIL-12. Animal groups immunized with pE7 + pIL-12 on the same leg showed a complete loss of antigen-specific CTL lytic activity as we previously observed (Fig. 1). Animals immunized with pE7 on the right leg and with pIL-12 on the left leg also displayed a complete loss of antigen-specific CTL lytic activity, consequently giving no antitumour protection from a tumour cell challenge. Similarly, no IFN-γ production from CD8+ CTL was observed when animals were immunized with pE7 on the right leg and with pIL-12 on the left leg (data not shown). These data imply that IL-12 can inhibit induction of E7-specific CTL responses in a systemic manner.

Figure 4.

Effect of separate injection of interleukin-12 (IL-12) and E7 complementary DNAs on antigen-specific antibody (a) and T helper (Th) cell proliferative (b), cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) (c), and tumour protective (d) responses. (a) Each group of animals (n = 5) was immunized intramuscularly with 50 μg pE7 on the right leg and with 50 μg of pIL-12 on the left leg at 0, 2 and 4 weeks. pcDNA3 was used as a negative control. At 6 weeks, mice were bled and then each serum per group was diluted to 1 : 50 for reaction with E7 in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. (b, c) The above animals were killed to obtain splenocytes. The pooled splenocytes were tested for Th cell proliferative responses (b) and CTL lytic activity (c) as shown in the Materials and methods section. Samples were assayed in triplicate. (d) Each group of animals (n = 5) was immunized as above. At 6 weeks, animals were challenged subcutaneously with 3 × 104 TC-1 cells per mouse and then tumour sizes were measured over time. Values and bars represent means of OD values, % lysis and tumour sizes, and the SD, respectively. These experiments were repeated with similar results. *Statistically significant at P < 0·05 using the independent-samples t-test compared to negative control.

Effects of pE7 + pIL-12 cotransfection on E7 protein expression levels in vitro

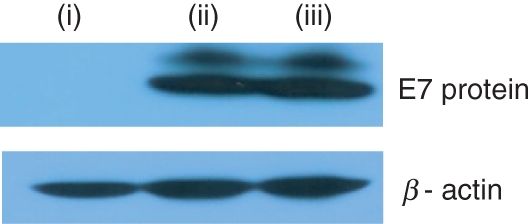

We hypothesized that in vivo suppression of E7-specific immune responses, in particular antibody and Th cell responses, by local coinjection of IL-12 cDNA might be the result of decreased expression levels of E7 proteins by IL-12 cDNA codelivery. To test this theory, we transfected rhabdomyosarcoma cells in vitro with pE7 and pIL-12, and then evaluated E7 expression levels using SDS–PAGE and Western blot assay. As shown in Fig. 5, no difference was detected in E7 protein expression levels between the cells transfected with pE7 + pIL-12 and those with pE7 + pcDNA3. These data suggest that the observed immune suppression might not result from decreased E7 expression by IL-12 cDNA coinjection.

Figure 5.

Determination of E7 expression levels by cotransfection in vitro with E7- and IL-12-expressing plasmids. Rhabdomyosarcoma cells were cotransfected in vitro with 2 μg pE7 and 2 μg pcDNA3 or pIL-12 (1 μg of pcDNA3-IL-12 p35 + 1 μg of pcDNA3-IL-12 p40). One day after transfection, cells were collected. Forty micrograms of the cell lysates were run on sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for Western blot assay. (i) pcDNA3, (ii) pE7 + pcDNA3 and (iii) pE7 + pIL-12.

Effects of IFN-γ on antigen-specific humoral responses and CTL-mediated antitumour protection

We hypothesized that IFN-γ might be a key mediator of this suppression. This hypothesis is based upon previous reports that IFN-γ is involved in the inhibition of antibody and Th cell proliferative responses by IL-12 in a DNA vaccine model.28 To confirm that IFN-γ is induced by IL-12 cDNA injection, we evaluated sera levels of both IL-12 and IFN-γ following IL-12 cDNA injection. The IL-12 levels peaked at 5 days after IL-12 cDNA injection and then declined to a background at 10 days post-injection (Fig. 6a). In contrast, IFN-γ levels increased gradually and peaked at 7 days after IL-12 cDNA injection, and were maintained even at 10 days post-injection. These data show that IL-12 delivered in a DNA form can express a bioactive IL-12, resulting in induction of IFN-γ. To further determine any roles of IFN-γ in IL-12-mediated immune suppression, we immunized IFN-γ KO animals with E7 DNA vaccine alone or in combination with IL-12 cDNA. As shown in Fig. 6(c), E7 DNA vaccine (pE7) alone significantly induced antigen-specific IgG production in IFN-γ KO animals while coinjection of pE7 plus pIL-12 suppressed antigen-specific antibody production, suggesting no involvement of IFN-γ in this IL-12-mediated antibody suppression. When IFN-γ KO animals were immunized with E7 DNA vaccine alone or in combination with IL-12 cDNA, antitumour protection from TC-1 tumour cell challenges was not observed (Fig. 6d). Furthermore, no CTL was detected in these IFN-γ KO animals (data not shown).

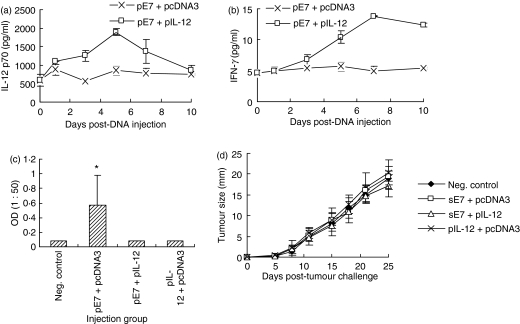

Figure 6.

Effects of E7 and interleukin-12 (IL-12) complementary DNA coinjection on sera production of IL-12 and interferon-γ (IFN-γ), and on antigen-specific immune and tumour protective responses in IFN-γ knockout (KO) mice. (a, b) Wild-type mice were injected intramuscularly with pE7 + pcDNA3 and pE7 + pIL-12 using a 50 μg dose of each construct and sera were collected at the indicated time-points for evaluating sera levels of IL-12 (a) and IFN-γ (b) by sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. (c, d) Each group of IFN-γ KO mice (n = 5) was immunized intramuscularly with 50 μg pE7 and 50 μg pIL-12 at 0, 2 and 4 weeks. pcDNA3 was used as a negative control. At 6 weeks, the animals were bled for evaluation of E7-specific humoral responses (c) and then challenged subcutaneously with 3 × 104 TC-1 tumour cells per mouse for measurement of tumour protective responses (d). Values and bars represent means of cytokines, optical density (OD) and tumour sizes, and the SD, respectively. *Statistically significant at P < 0·05 using the independent-samples t-test compared to negative control.

Effects of nitric oxide on antigen-specific humoral responses, CTL responses, IFN-γ production and tumour protective responses

It has been reported that nitric oxide is involved in immune regulation.29 So, we investigated whether nitric oxide plays any roles in IL-12-mediated immune suppression. For this, we immunized NOS2 KO animals with E7 DNA vaccine alone and in combination with IL-12 cDNA. As shown in Fig. 7(a), E7 DNA vaccine (pE7) alone induced antigen-specific antibody responses to a significant level in NOS2 KO animals, whereas pE7 + pIL-12 suppressed antigen-specific antibody production. These data suggest that nitric oxide is not involved in IL-12-mediated antibody suppression. When NOS2 KO animals were immunized with pE7, antigen-specific CTL responses were significantly induced (Fig. 7b). Furthermore, a significant induction of antigen-specific CTL responses was also observed when NOS2 KO animals were immunized with pE7 + pIL-12. A similar finding was observed in the profiles of both antigen-specific IFN-γ production from CD8+ CTL (Fig. 7c) and tumour protective responses (Fig. 7d). These data reflect that nitric oxide plays an important role in suppressing E7-specific CTL responses by IL-12 cDNA coinjection, but not E7-specific antibody responses.

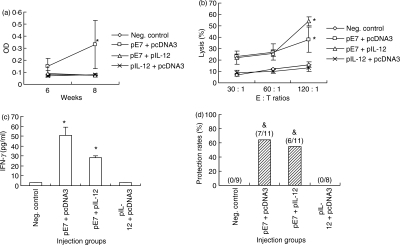

Figure 7.

Effect of E7 and interleukin-12 (IL-12) complementary DNA coinjection on antigen-specific antibody (a), cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) (b), interferon-γ (IFN-γ) (c) and tumour protective responses (d) in NOS2 knockout (KO) mice. (a) Each group of NOS2 KO mice (n = 5) was immunized intramuscularly with 50 μg pE7 and 50 μg pIL-12 at 0, 2, 4 and 6 weeks. pcDNA3 was used as a negative control. At 6 and 8 weeks, mice were bled and then each serum per group was diluted to 1 : 50 for reaction with E7 in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. (b, c) Each group of NOS2 KO mice (n = 5) was immunized intramuscularly with 50 μg pE7 and 50 μg pIL-12 at 0, 2 and 4 weeks. pcDNA3 was used as a negative control. At 6 weeks, mice were killed and splenocytes were obtained. The pooled splenocytes were tested for CTL lytic activity (b) and IFN-γ induction levels (c), as shown in the Materials and methods section. Samples were assayed in triplicate. Values and bars represent means of optical density (OD), % lysis and IFN-γ values, and the SD, respectively. *Statistically significant at P < 0·05 using the independent-samples t-test compared to negative control. (d) Each group of NOS2 KO mice (n = 4 to n = 6) was immunized intramuscularly with 50 μg pE7 and 50 μg pIL-12 at 0, 2 and 4 weeks. pcDNA3 was used here as a negative control. At 6 weeks, mice were challenged subcutaneously with 3 × 104 TC-1 cells per mouse and then tumour sizes were measured over time. The percentage of animals without tumour formation at 30 days post-tumour challenge was shown. The numbers in parentheses denote the number of mice without tumour formation/the number of mice tested at 30 days after tumour challenge and represent a combination of two experiments. &Statistically significant at P < 0·05 using the chi-squared test compared to negative control.

Discussion

In this study, we found that coinjection of HPV E7 DNA vaccine with IL-12 cDNA completely suppresses antigen-specific CTL responses, leading to a loss of antitumour protective capacity. These unexpected data are in direct contrast to those in the literature showing enhanced antigen-specific T-cell proliferative and CTL responses to codelivered DNA vaccines by IL-12 cDNA coinjection in HIV and influenza virus models.13,14 The present observation is also not in line with our previous reports that coinjection with IL-12 cDNA augments protective immunity against challenges with encephalomyocarditis virus and herpes simplex virus, resulting from augmented antigen-specific antibody or cellular immune responses.11,12,30 In our previous tumour vaccine studies, furthermore, we found that antigen-specific CTL-mediated antitumour therapeutic responses are enhanced to a more dramatic degree when recombinant E7 proteins are codelivered intratumorally with an adenoviral vector expressing IL-12.22 A similar finding was also reported in the bacterial delivery of E7 and IL-12.31 In the present study, it is notable that antigen-specific antibody and Th cell proliferative responses were also suppressed by IL-12 cDNA coinjection. Previously, others, including us,12,13,28,32 reported that antigen-specific antibody induction tends to be down-regulated by IL-12 cDNA coinjection, depending on its dosage. Interleukin-12 doses have been thought to be an important factor in regulating the immune responses. For instance, antigen-specific antibody responses were increased when herpes simplex virus-2 gD DNA vaccine was coinjected with a lower dose of IL-12 cDNA, whereas the responses were decreased when gD DNA vaccine was coinjected with a higher dose of IL-12 cDNA.12 In the present study, however, we observed that coinjection with a lower dose of IL-12 cDNA, even at 10 μg/mouse, abolishes E7-specific IgG and Th cell proliferative responses. This discrepancy in IL-12 cDNA dose effects on antigen-specific immune regulation might be explained by differences in the immunogenic and biochemical properties of the antigens tested. For example, we routinely observed that E7 DNA vaccine induced a far lower degree of antibody production at the given doses, as compared with antigens including gD (viral membrane protein) or VP1 (viral coat protein) that we tested previously (data not shown). Furthermore, E7 DNA vaccine was constructed for targeting its expressed proteins into the endolysosomal compartment of a cell.9 These differences might contribute to increased sensitivity of E7 to IL-12 for antigen-specific immune suppression. This finding further suggests that the adjuvant effect of IL-12 is dependent on the antigen types tested.

Immune suppression by IL-12 treatment has been known to correlate well with its ability to induce IFN-γ production in immune cells.29,33 High levels of IFN-γ can activate macrophages and induce nitric oxide synthase activity to generate nitric oxide which impairs T-cell responses.29 In accordance with this, IL-12 cDNA coinjection had no negative effect of antigen-specific immune induction in IFN-γ KO mice.28 Unexpectedly, we failed to see any recovery of IL-12-mediated E7-specific antibody suppression in IFN-γ and NOS2 KO animals, suggesting that IFN-γ and nitric oxide are not directly associated with IL-12-mediated suppression of E7-specific antibody responses. It is possible that the immune suppression might occur through a decreased antigen expression by IL-12 cDNA coinjection. However, this is unlikely as cotransfection of E7 expression vectors with IL-12 expression vector failed to reduce the expression of E7 proteins in vitro. In parallel with the previous report demonstrating nitric oxide as a negative factor for immune induction, IL-12 cDNA coinjection failed to suppress antigen-specific CTL and tumour protective responses in NOS2 KO mice, confirming that IL-12 suppresses antigen-specific CTL responses through nitric oxide, leading to a complete loss of antitumour protective immunity against tumour cell challenges. In this case, a positive correlation between antitumour resistance and the in vitro levels of CTL lytic activity and IFN-γ production from CD8+ T cells was seen here as previously reported by us.9,10 In view of the observed immune suppression patterns by IL-12 cDNA coinjection, it seems that IL-12 behaves differently for regulating antibody versus CTL responses. This notion is further supported by our observation that antigen-specific antibody and Th cell proliferative responses were not suppressed by separate leg injections of E7 DNA vaccine and IL-12 cDNA, whereas antigen-specific CTL and tumour protective responses were suppressed by the separate injection. This finding also suggests that IL-12-mediated suppression of MHC class I-mediated CD8+ CTL responses is systemically regulated. However, it is still unclear how IL-12 suppresses E7-specific antibody responses. It can be speculated that IL-12-induced pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF), might induce nitric oxide-independent cytotoxicity for antibody suppression. This is based upon the previous reports that high doses of IL-12 induce serum TNF production34 and that TNF can mediate cell killing directly.35 Moreover, coinjection of E7 DNA vaccine with TNF-α cDNA suppressed antigen-specific antibody responses but not CTL and tumour protective responses (data not shown). If this is the case, the amount of soluble TNF-α induced by IL-12 should be limited only for generation of local activity as we failed to see antigen-specific antibody suppression when E7 DNA vaccine was injected separately from IL-12 cDNA. However, this issue remains to be further clarified.

In conclusion, the data presented here suggest that coinjection of IL-12 as a DNA vaccine adjuvant could be detrimental to antigen-specific CTL induction for antitumour protective immunity in an HPV 16 E7 DNA vaccine model. This IL-12-mediated CTL suppression appeared to be mediated by nitric oxide, as determined by NOS2 knockout animal studies. Consequently, IL-12 suppresses antigen-specific CTL responses through nitric oxide, thereby giving no antitumour protective immunity in an E7 DNA vaccine model.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Dr Young Chul Sung for providing C57BL/6 IFN-γ KO mice. The author is also grateful for the technical assistance of Ms Y. J. Park for this study. This work was supported by the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (KOSEF) grant funded by the Korea government (R01-2005-000-10158-0).

Disclosures

I do not have any potential conflicts of interest in any company, institution or state that might benefit from the publication.

References

- 1.zur Hausen H. Human papillomaviruses in the pathogenesis of anogenital cancer. Virology. 1991;184:9–13. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90816-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scheffner M, Munger K, Bryne JC, Howley PM. The state of the p53 and retinoblastoma genes in human cervical carcinoma cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:5523–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Werness BA, Levine AJ, Howley PM. Association of HPV type 16 and 18 E6 protein with p53. Science. 1990;248:76–9. doi: 10.1126/science.2157286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dyson N, Howley PM, Munger K, Harlow E. The human papillomavirus-16 E7 oncoprotein is able to bind the retinoblastoma gene product. Science. 1989;243:934–7. doi: 10.1126/science.2537532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sin JI. Human papillomavirus vaccines for the treatment of cervical cancer. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2006;5:783–92. doi: 10.1586/14760584.5.6.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sin JI. Promises and challenges of human papillomavirus vaccines for cervical cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9:1–5. doi: 10.1586/14737140.9.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim TW, Hung CF, Ling M, Juang J, He L, Hardwick JM, Kumar S, Wu TC. Enhancing DNA vaccine potency by coadministration of DNA encoding antiapoptotic proteins. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:109–17. doi: 10.1172/JCI17293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim TW, Hung CF, Boyd DA, He L, Lin CT, Kaiserman D, Bird PI, Wu TC. Enhancement of DNA vaccine potency by coadministration of a tumor antigen gene and DNA encoding serine protease inhibitor-6. Cancer Res. 2004;64:400–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim MS, Sin JI. Both antigen optimization and lysosomal targeting are required for enhanced anti-tumour protective immunity in a human papillomavirus E7-expressing animal tumour model. Immunology. 2005;116:255–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sin JI, Hong SH, Park YJ, Park JB, Choi YS, Kim MS. Antitumor therapeutic effects of E7 subunit and DNA vaccines in an animal cervical cancer model: antitumor efficacy of E7 therapeutic vaccines is dependent on tumor sizes, vaccine doses, and vaccine delivery routes. DNA Cell Biol. 2006;25:277–86. doi: 10.1089/dna.2006.25.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sin JI, Kim JJ, Boyer JD, Higgins TJ, Ciccarelli RB, Weiner DB. In vivo modulation of vaccine-induced immune responses toward a Th1 phenotype increases potency and vaccine effectiveness in a herpes simplex virus type 2 mouse model. J Virol. 1999;73:501–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.501-509.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sin JI, Kim JJ, Arnold RL, et al. Interleukin-12 gene as a DNA vaccine adjuvant in a herpes mouse model: IL-12 enhances Th1 type CD4+ T cell mediated protective immunity against HSV-2 challenge. J Immunol. 1999;162:2912–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim JJ, Ayyavoo V, Bagarazzi ML, Chattergoon MA, Dang K, Wang B, Boyer JD, Weiner DB. In vivo engineering of a cellular immune response by co-administration of IL-12 expression vector with a DNA immunogen. J Immunol. 1997;158:816–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iwasaki A, Stiernholm BJ, Chan AK, Berstein NL, Barber BH. Enhanced CTL responses mediated by plasmid DNA immunogens encoding costimulatory molecules and cytokines. J Immunol. 1997;158:4591–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu WG, Ogawa M, Mu J, Umehara K, Tsujimura T, Fujiwara H, Hamaoka T. IL-12-induced tumor regression correlates with in situ activity of IFN-gamma produced by tumor-infiltrating cells and its secondary induction of anti-tumor pathways. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;62:450–7. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.4.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dias S, Thomas H, Balkwill F. Multiple molecular and cellular changes associated with tumor stasis and regression during IL-12 therapy of a murine breast cancer model. Int J Cancer. 1998;75:151–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980105)75:1<151::aid-ijc23>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robertson MJ, Soiffer RJ, Wolf SF, Manley TJ, Donahue C, Young D, Hermann SH, Ritz J. Responses of human natural killer (NK) cells to NK cell stimulatory factor (NKSF): cytolytic activity and proliferation of NK cells are differentially regulated by NKSF. J Exp Med. 1992;175:779–88. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.3.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobayashi M, Fitz L, Ryan M, et al. Identification and purification of natural killer cell stimulator factor (NKSF): a cytokine with multiple biologic effects on human lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1989;170:827–45. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.3.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Germann T, Gately MK, Schoenhaut DS, et al. Interleukin-12/T cell stimulating factor, a cytokine with multiple effects on T helper type 1 (Th1) but not on Th2 cells. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:1762–70. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim TY, Myoung HJ, Kim JH, Moon IS, Kim TG, Ahn WS, Sin JI. Both E7 and CpG-ODN are required for protective immunity against challenge with human papillomavirus 16 (E6/E7)-immortalized tumor cells: involvement of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in protection. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7234–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim TG, Kim CH, Won EH, Bae SM, Ahn WS, Park JB, Sin JI. CpG-ODN-stimulated dendritic cells act as a potent adjuvant for E7 protein delivery to induce antigen-specific anti-tumor immunity in a HPV 16 (E6/E7)-associated tumor animal model. Immunology. 2004;112:117–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01851.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahn WS, Bae SM, Kim TY, Kim TG, Lee JM, Namkoong SE, Kim CK, Sin JI. A therapy modality using recombinant IL-12 adenovirus plus E7 protein in a human papillomavirus 16 E6/E7-associated cervical cancer animal model. Hum Gene Ther. 2003;14:1389–99. doi: 10.1089/104303403769211619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ye GW, Park JB, Park YJ, Choi YS, Sin JI. Increased sensitivity of radiated murine cervical cancer tumors to E7 subunit vaccine-driven CTL-mediated killing induces synergistic antitumor activity. Mol Ther. 2007;15:1564–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feltkamp MC, Smits HL, Vierboom MP, et al. Vaccination with cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope-containing peptide protects against a tumor induced by human papillomavirus type 16-transformed cells. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2242–9. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng WF, Hung CF, Hsu KF, et al. Cancer immunotherapy using Sindbis virus replicon particles encoding a VP22-antigen fusion. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13:553–68. doi: 10.1089/10430340252809847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hung CF, Cheng WF, Hsu KF, Chai CY, He L, Ling M, Wu TC. Cancer immunotherapy using a DNA vaccine encoding the translocation domain of a bacterial toxin linked to a tumor antigen. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3698–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lamikanra A, Pan ZK, Isaacs SN, Wu TC, Paterson Y. Regression of established human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV-16) immortalized tumors in vivo by vaccinia viruses expressing different forms of HPV-16 E7 correlates with enhanced CD8(+) T-cell responses that home to the tumor site. J Virol. 2001;75:9654–64. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.20.9654-9664.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen H-W, Pan C-H, Huann H-W, Liau M-Y, Chiang J-R, Tao MH. Suppression of immune response and protective immunity to a Japanese encephalitis virus DNA vaccine by coadministration of an IL-12-expressing plasmid. J Immunol. 2001;166:7419–26. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lasarte JJ, Corrales FJ, Casares N, Lopez-Diaz de Cerio A, Qian C, Xie X, Borras-Cuesta F, Prieto J. Different doses of adenoviral vector expressing IL-12 enhance or depress the immune response to a coadministered antigen: the role of nitric oxide. J Immunol. 1999;162:5270–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suh Y-S, Ha S-J, Lee C-H, Sin JI, Sung YC. Enhancement of VP1-specific immune responses and protection against EMCV-K challenge by codelivery of VP1 with IL-12 plasmid DNAs. Vaccine. 2001;19:1891–8. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00443-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bermudez-Humaran LG, Cortes-Perez NG, Lefevre F, et al. A novel mucosal vaccine based on live Lactococci expressing E7 antigen and IL-12 induces systemic and mucosal immune responses and protects mice against human papillomavirus type 16-induced tumors. J Immunol. 2005;175:7297–302. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoon HA, Aleyas AG, George JA, et al. Modulation of immune responses induced by DNA vaccine expressing glycoprotein B of Pseudorabies virus via coadministration of IFN-γ-associated cytokines. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2006;26:730–8. doi: 10.1089/jir.2006.26.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mazzolini G, Narvaiza I, Perez-Diez A, et al. Genetic heterogeneity in the toxicity to systemic adenoviral gene transfer of interleukin-12. Gene Ther. 2001;8:259–67. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orange JS, Wolf SF, Biron CA. Effects of IL-12 in the responses and susceptibility to experimental viral infections. J Immunol. 1994;152:1253–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tartaglia LA, Ayres TM, Wong GH, Goeddel DV. A novel domain within the 55 kd TNF receptor signals cell death. Cell. 1993;74:845–53. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90464-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]