Iron and copper are redox-active metals essential for life.[1,2] Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is also essential for cellular activities[3,4] and has recently been identified as a second messenger.[3] However, iron, copper, and H2O2 are all “double-edged swords” because they can be extremely toxic to cells at high concentrations. The chemical nature of this toxicity is largely a result of the Fenton reaction [Eq. (1)],[5]

| (1) |

which generates highly deleterious hydroxyl radicals (HO·, half-life ≈ 1 ns). Cellular reductants, such as hydroascorbate (AscH−) and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH), can recycle FeIII (or CuII) back to FeII (or CuI) [Eq. (2)], thus making the Fenton reaction catalytic when excess H2O2 is available.

| (2) |

The occurrence of the Fenton reaction in living cells has long been speculated on and has recently been unambiguously detected by EPR spin-trap techniques.[4] It has been revealed that iron and copper are accumulated in the brain with age and are concentrated in certain areas of the brain in patients with neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson's disease (PD) and Alzheimer's disease (AD).[6] Moreover, the production of H2O2 is significantly elevated and its elimination mechanisms become impaired in patients with neuro-degenerative diseases.[7] The Fenton reaction has been implicated as a cause of the aging process and contributes to the pathogenesis of PD and AD,[7,8] supported by the observation of oxygen-radical-triggered brain damage in PD/AD patients.[9] Metal-chelating agents, such as desferrioxamine and clioquinol, have shown promise in AD/PD treatment.[9–11] However, these chelators have troublesome drawbacks, such as accession of intracellular iron pools or prooxidant effects.[12,13] Their high metal affinities and unregulated chelating properties may disrupt healthy metal homeostasis by depleting the essential cellular labile iron pool, thus removing metal from enzymes that rely on Fe (or Cu) and disrupting the levels of other metal ions, such as zinc and calcium.

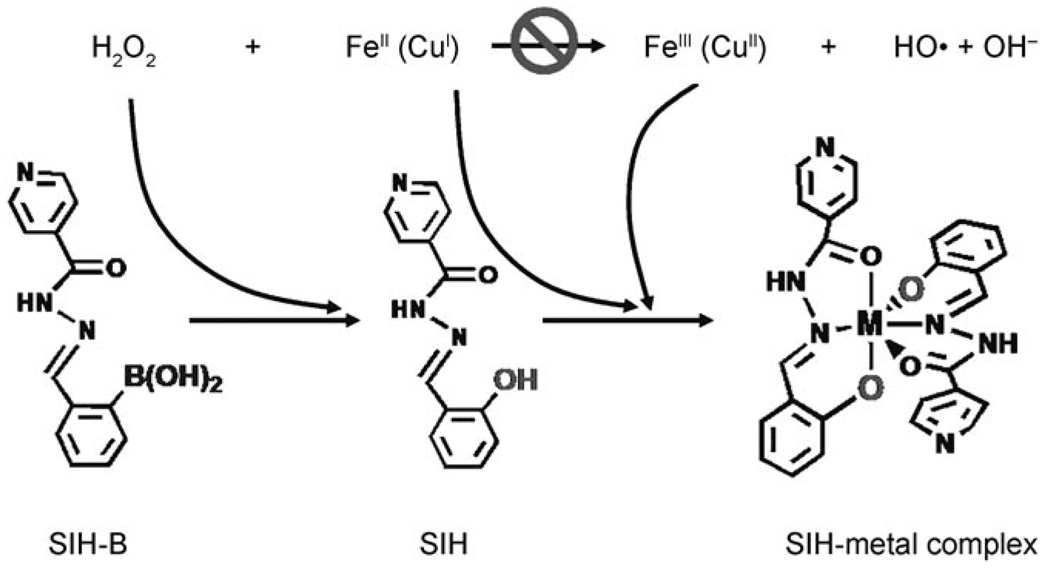

To develop novel agents capable of attenuating the Fenton reaction while also overcoming the drawbacks of the uncontrolled chelators, we have synthesized prochelators that cannot chelate metal ions by themselves but can be activated by H2O2, with subsequent attenuation of the Fenton reaction (Scheme 1). As the process involves consumption of H2O2, sequestration of metal, and prevention of the production of hydroxyl radicals, we may tentatively call it an “anti-Fenton reaction”. Our ultimate goal is to develop agents that have minimal interference with iron (or other redox metals) under healthy conditions, but which chelate metals and attenuate the Fenton reaction at toxic levels of H2O2 or other reactive oxygen species (ROS).

Scheme 1.

“Anti-Fenton reaction”.

Herein, we report our first prochelator 2-boronobenzaldehyde isonicotinoyl hydrazone (SIH-B), which may be considered as a derivative of salicylaldehyde isonicotinoyl hydrazone (SIH). SIH has been widely investigated as one of the orally effective tridentate iron chelators.[14] In neutral aqueous media, SIH binds strongly to both FeIII and FeII with the formation of Fe(SIH) and Fe(SIH)2 complexes, in which coordination to Fe occurs through the coplanar tridentate donors: the phenolic group C6H4–O−, the C=O group, and the NH–N group of the hydrazone. [15,16]

As shown in Scheme 1, the structural difference between the prochelator SIH-B and the chelator SIH is that the phenol oxygen in SIH, a key chelating atom, is replaced by a boronic acid group in the prochelator SIH-B. The hypothesis is that the steric hindrance and poor donor property of the boronic acid group may cause SIH-B to be a poor chelator. The protecting boronic acid group in SIH-B may be sensitive to H2O2, and thus may be converted to a phenol group by H2O2, that is, be “activated” to produce the active chelator SIH.

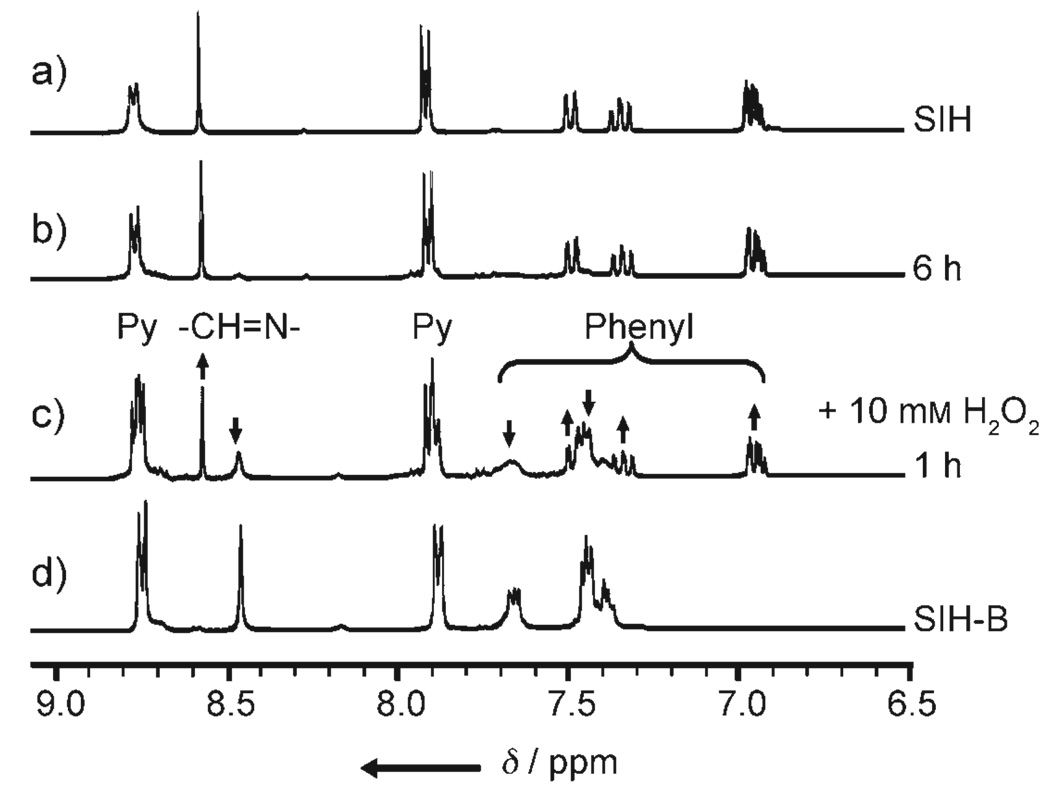

SIH is synthesized by the Schiff base condensation reaction of isoniozid with 2-formylphenol, as described previously.[15] SIH-B is synthesized similarly but with 2-formylphenylboronic acid instead of 2-formylphenol (see Supporting Information). As a result of the marked differences in the NMR and UV/Vis characteristics of SIH and SIH-B (Figures S1 and S2 in the Supporting Information), 1H NMR and UV/Vis experiments were carried out to probe the reaction of SIH-B and H2O2. As shown in Figure 1, upon addition of H2O2 to SIH-B in methanol, the 1H NMR peaks for SIH-B [δ = 8.45 (s; −CH=N−), 7.63 (t), 7.37–7.45 ppm (m; aromatic ring)] gradually decreased in intensity while the peaks corresponding to SIH [δ = 8.55 (s; −CH=N−), 7.48 (d), 7.35 (t), 6.94 ppm (m; aromatic ring)] appeared simultaneously and increased in intensity with time. Other peaks [δ = 8.75 (d) and 7.88 ppm (d; pyridine ring)] also underwent similar conversions but with very small changes in chemical shifts. In about 2 h, SIH-B was cleanly converted to SIH with no intermediate formed, as indicated by the 1H NMR spectra. The reaction was also followed by UV/Vis difference spectroscopy (Figure S3 in the Supporting Information) in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF)/potassium phosphate buffer (KPB; 20 mm, pH 7.2; 1:1 v/v). With tenfold excess H2O2, the conversion reaction is pseudo-first order with an apparent rate constant (kobs) of 1.33 × 10−3 s−1, comparable to that of a boronic ester analogue.[17] These results demonstrate that SIH-B can be cleanly converted to SIH by H2O2 under physiological pH conditions.

Figure 1.

1H NMR spectra (in [D4]MeOH) of a) SIH (1 mm), the reaction of SIH-B (1 mm) with H2O2 (10 mm) after b) 6 and c) 1 h at 293 K, and d) SIH-B (1 mm).

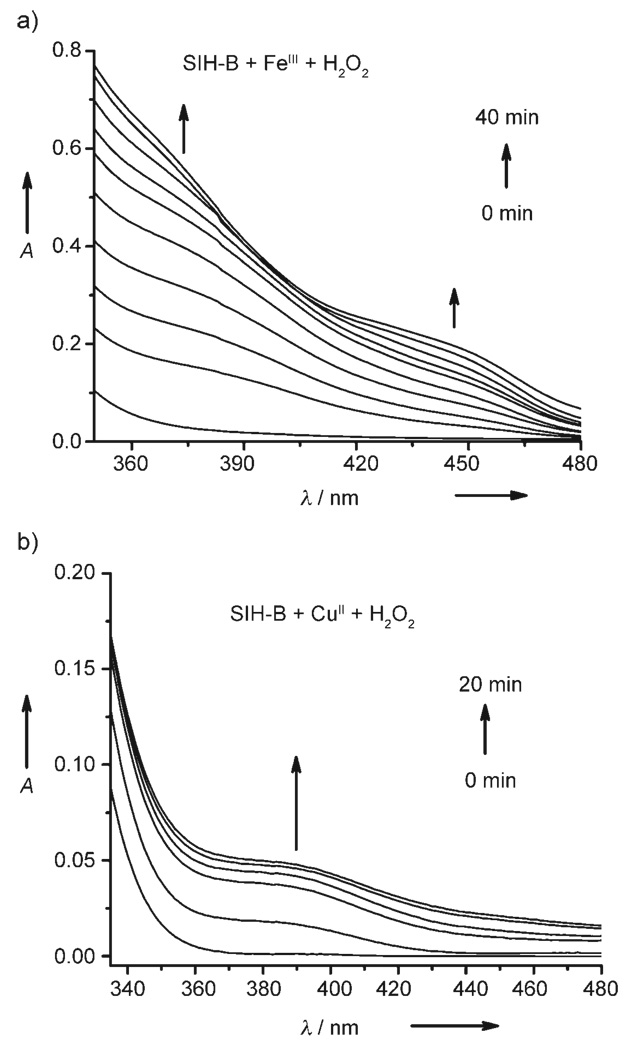

Next, we investigated whether SIH-B can chelate iron (or copper) under physiologically relevant conditions and if the chelation can be triggered by H2O2. As controls, we also monitored the coordination of SIH with FeIII or CuII under similar conditions. Titration of FeIII or CuII into SIH solution immediately produces new broad absorption bands in the visible region (360–500 nm) (Figures S4 and S5 in the Supporting Information), which match those reported previously.[16,18] These bands were assigned to O→metal charge-transfer (CT) absorption and internal ligand transitions, thus suggesting the formation of specific SIH–metal complexes. However, when similar titration experiments were carried out with the prochelator SIH-B (Figure S6 in the Supporting Information), no absorption band was observed in the visible region when FeIII or CuII was titrated. The absence of ligand–metal CT (LMCT) absorption suggests little or no interaction between the prochelator SIH-B with FeIII or CuII under the conditions applied.

Interestingly, upon addition of H2O2 to the SIH-B/FeIII or SIH-B/CuII mixture, characteristic LMCT bands (Figure 2) emerged and increased in intensity over 40 and 20 min, respectively. The spectroscopic changes are consistent with the formation of SIH–FeIII or SIH–CuII complexes, thus implying that H2O2 “activates” SIH-B to SIH which subsequently chelates the metal ions.

Figure 2.

UV/Vis spectra of the time course of the reactions after the addition of H2O2 (0.5 mm) to a) a mixture of SIH-B (50 µm) and FeCl3 (25 µm), and b) a mixture of SIH-B (50 µm) and CuCl2 (25 µm). The H2O2-triggered reactions were incubated in DMF/KPB (pH 7.2) at 298 K with stirring and measured at intervals of 5 min.

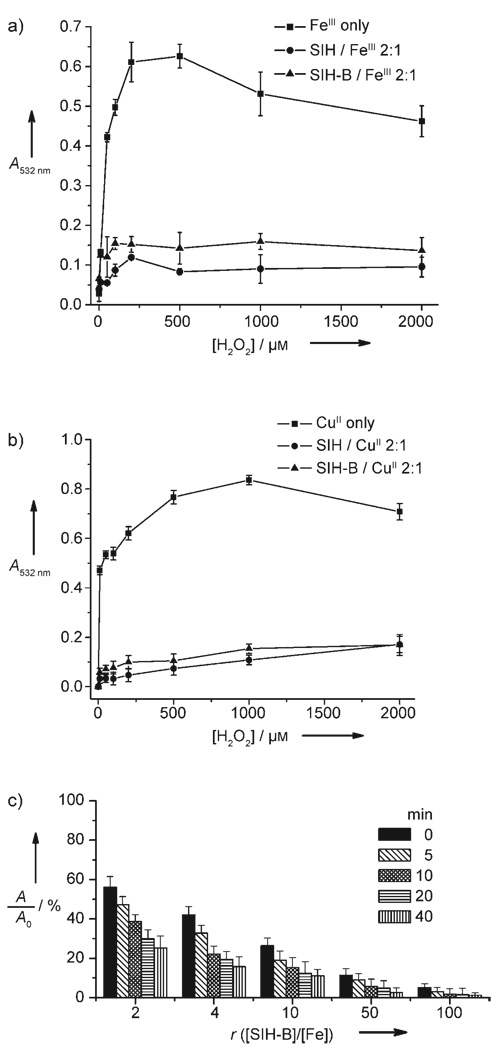

Finally, we tested whether SIH-B can inhibit the Fenton reaction under physiologically relevant conditions. SIH, which is known to inhibit the Fenton reaction,[19] was used for comparison. Fenton reactions were generated according to Equation (1) and Equation (2) by incubating FeCl3, FeCl2, or CuCl2 with H2O2 in the presence of hydroascorbate in KPB (20 mm, pH 7.2). 2-Deoxyribose (10 mm) was also added as a substrate for hydroxyl radicals in the assay. The production of HO· radicals was monitored by quantification of the 2-deoxyribose degradation product, malonaldehyde (MDA), by its condensation with thiobarbituric acid (TBA) to form a chromophore with characteristic absorption at 532 nm.[19] We used the 2-deoxyribose degradation assay to measure the ability of SIHB to prohibit the formation of HO· radicals. As shown in Figure 3 and Figure S7 in the Supporting Information, it is apparent that at a ligand-to-metal ratio of 2:1, both SIH-B and SIH significantly prevent 2-deoxyribose degradation caused by hydroxyl radicals that are generated by either Fe- or Cu-promoted Fenton chemistry. However, if a ligand-to-metal ratio of 1:1 was used under similar conditions, a marked decrease in protection was observed (Figure S8 in the Supporting Information). SIH is a tridentate ligand, and thus metal-SIH (1:1) complexes may offer open coordination sites for H2O2 to access the metal, while the metal-(SIH)2 complexes are coordination saturated, which may completely block the access of H2O2. This finding suggests that a “caged” metal configuration without any open coordination sites is important for attenuating the Fenton reaction.

Figure 3.

Effect of SIH and SIH-B on the oxidative degradation of 2-deoxyribose promoted by a) FeIII or b) CuII in the presence of H2O2 and hydroascorbate. SIH-B (50 µm) was preincubated with H2O2 for 45 min at 298 K, then the solution (0.5 mL) was added to the assay system containing FeIII (or CuII; 25 µm), 2-deoxyribose (10 mm), and hydroascorbate (200 µm) in KPB (20 mm, pH 7.2). c) Effect of preincubation time (0, 5, 10, 20, 40 min) and [SIH-B]/[Fe] ratio (r) on attenuation of FeII-promoted Fenton chemistry in KPB buffer (20 mm, pH 7.2). [Fe] = 10 µm, [H2O2] = 200 µm; A and A0 are the absorbance at 532 nm in the presence and absence of SIH-B, respectively.

As shown in Figure 3c, the effectiveness of SIH-B in the attenuation of Fe-promoted Fenton chemistry is correlated with the SIH-B/Fe ratio and also its preincubation time with H2O2. At a low SIH-B/Fe ratio (< 10), a preincubation period (≈ 10 min) between SIH-B and H2O2 is important for SIH-B to be effective in attenuating the Fenton reaction. Better attenuation is observed with increasing preincubation time from 0 to 40 min. This observation may result from the fact that the conversion of SIH-B to SIH by H2O2 is the rate-limiting step. However, at high SIH-B/Fe ratio (> 10), the attenuation is more effective and preincubation appears less important. Taken together, the results support H2O2-triggered prochelator SIH-B activation followed by metal sequestering as a likely mechanism for attenuating the Fe (or Cu)- promoted Fenton reaction. Studies performed with iron concentrations from 0.5 to 20 µm (Figure S9 in the Supporting Information) and over the pH range of 5.84 to 9.10 (Figure S10 in the Supporting Information) demonstrate that SIH-B is effective in inhibiting the Fenton reaction at physiologically relevant iron concentrations and pH range.

In summary, we have developed a prochelator SIH-B, which can be converted to the active chelator SIH by H2O2 for subsequent sequestration of iron and copper. This process can effectively attenuate both Fe- and Cu-promoted Fenton reactions under physiologically relevant conditions. The H2O2-sensed chelating reactivity has interesting characteristics that allow its consideration as a strategy to develop novel compounds for attenuating the Fenton reaction under oxidative stress conditions without disturbing healthy metal homeostasis. Given the high levels of Fe (or Cu) and ROS in brain tissues with certain neurodegenerative diseases, as well as their critical roles in cardiovascular disease and certain cancers, reagents capable of producing an “anti-Fenton reaction” may be promising candidates for potential therapeutics. Notably, the activation step of the current system is relatively slow and thus improvement is warranted.

Experimental Section

Freshly prepared solutions of FeCl3 (or CuCl2) in methanol and FeCl2 in dilute HCl were used. For titration experiments, a solution of the metal ion was added to SIH-B or SIH (stock solutions in MeOH) and the mixture was equilibrated at 298 K for 10 min. All titrations were performed in KPB/DMF solvent unless otherwise noted.

UV/Vis spectra were recorded on a PerkinElmer Lambda 25 spectrometer at 298 K. UV difference spectra were recorded immediately after addition of H2O2 to SIH-B and at different time intervals. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AC 300 spectrometer, and FTIR spectra were recorded on a Nicolet 4700 FTIR spectrometer. The 2-deoxyribose degradation assays were performed similarly to the method reported by Lopes et al.[19]

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

We thank the American Parkinson Disease Association, National Parkinson Foundation, and University of Massachusetts Dartmouth for their support of this work. This publication or project was made possible by grant number 1 R21 AT002743-01A2 from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NCCAM, or the National Institutes of Health.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

Contributor Information

Yibin Wei, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth, MA 02747 (USA).

Dr. Maolin Guo, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth, MA 02747 (USA)

References

- 1.Crichton R. Inorganic Biochemistry of Iron Metabolism. 2nd ed. Chichester: Wiley; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo M, Bhaskar B, Li H, Barrows TP, Poulos TL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:5940. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306708101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Georgiou G, Masip L. Science. 2003;300:592. doi: 10.1126/science.1084976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park S, You X, Imlay JA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:9317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502051102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fenton HJH. J. Chem. Soc. Trans. 1894;65:899. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang X, Moir RD, Tanzi RE, Bush AI, Rogers JT. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004;1012:153. doi: 10.1196/annals.1306.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Krapfenbauer K, Engidawork E, Cairns N, Fountoulakis M, Lubec G. Brain Res. 2003;967:152. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)04243-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Tabner BJ, Turnbull S, El-Agnaf OMA, Allsop D. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2002;32:1076. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00801-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnham KJ, Masters CL, Bush AI. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2004;3:205. doi: 10.1038/nrd1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richardson DR. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004;1012:326. doi: 10.1196/annals.1306.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weinberg ED. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2006;58:575. doi: 10.1211/jpp.58.5.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Puglielli L, Friedlich AL, Setchell KDR, Nagano S, Opazo C, Cherny RA, Barnham KJ, Wade JD, Melov S, Kovacs DM, Bush AI. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:2556. doi: 10.1172/JCI23610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaston TB, Richardson DR. Am. J. Hematol. 2003;73:200. doi: 10.1002/ajh.10348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benvenisti-Zarom L, Chen J, Regan RF. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49:687. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richardson DR, Bernhardt PV. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 1999;4:266. doi: 10.1007/s007750050312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wis Vitolo LM, Hefter GT, Clare BW, Webb J. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1990;170:171. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dubois JE, Fakhrayan H, Doucet JP, El Hage Chahine JM. Inorg. Chem. 1992;31:853. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charkoudian LK, Pham DM, Franz KJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:12424. doi: 10.1021/ja064806w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koh LL, Kon OL, Loh KW, Long YC, Ranford JD, Tan AL, Tjan YY. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1998;72:155. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(98)10075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lopes GKB, Schulman HM, Hermes-Lima M. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 1999;1472:142. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(99)00117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.