Abstract

Liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry methods were developed to simultaneously determine the concentrations of angiotensin (Ang) II, Ang 1-7, Ang III and Ang IV in biological samples. The samples were extracted with C18 solid-phase extraction cartridges, and separated by a reverse-phase C18 column using acetonitrile in water with 0.1 % formic acid as a mobile phase. Angiotensin peptides were ionized by electrospray and detected by triple quadrupole mass spectrometry in the positive ion mode. (M+3H)3+ and (M+2H)2+ ions were chosen as the detected ions in the single ion recording (SIR) mode for LC-MS. The limits of detection (S/N=3) using SIR are 1 pg for Ang IV and 5 pg for Ang 1-7, Ang III and Ang II. Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode was used for LC-MS/MS. The limits of detection (S/N=3) using MRM are 20 pg for Ang IV and 25 pg for Ang 1-7, Ang III and Ang II. These methods were applied to analyze angiotensin peptides in bovine adrenal microvascular endothelial cells. The results show that Ang II is metabolized by endothelial cells to Ang 1-7, Ang III and Ang IV with Ang 1-7 being the major metabolite.

Keywords: Angiotensin II, mass spectrometry, liquid chromatography, electrospray ionization, adrenal cortex

Introduction

Angiotensin (Ang) peptides play a critical role in regulating vascular tone and electrolyte balance. Ang II (Asp-Arg-Val-Tyr-Ile-His-Pro-Phe) is the main effector of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS), and exerts its physiological effects by activating AT1 and AT2 receptors [1]. It constricts vascular smooth muscle, enhances the activity of the sympathetic nervous system and promotes aldosterone release from the adrenal gland [2]. In addition to effects on cardiovascular homeostasis, Ang II also contributes to the control of cellular growth [3–5]. Ang II can be further metabolized to several bioactive peptides, including Ang 1-7 (Asp-Arg-Val-Tyr-Ile-His-Pro), Ang III (Arg-Val-Tyr-Ile-His-Pro-Phe) and Ang IV (Val-Tyr-Ile-His-Pro-Phe). These peptides have several biologic functions. For example, Ang 1-7 has vasodilatory and antihypertensive actions that oppose Ang II [6–8]. Ang II and Ang III have similar affinities for AT1 and AT2 receptors and cause vasoconstriction and promote aldosterone secretion [9–11]. Ang IV has been implicated in a number of physiological actions, including the regulation of blood flow, the modulation of exploratory behavior, and processes attributed to learning and memory [12]. Ang III, Ang IV and Ang 1-7 also modulate blood pressure or cardiac function [13]. Therefore, the study of the formation of the angiotensin peptides could lead to the better understanding of mechanisms of cardiovascular diseases and the development of new therapies for the treatment of these diseases.

Analysis of Ang peptides has been performed using HPLC combined with radioimmunoassay [14–17]. This technique relies on specific antibodies for each peptide. There are significant drawbacks to the use of radioimmunoassay: disposal of radioactive materials, specificity and cross-reactivity of antibodies, and availability of the radiolabeled peptides. Therefore, it is highly desired to develop a method for the identification and quantification of Ang peptides in biological samples.

High performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) features high selectivity and high sensitivity. LC-MS is a useful tool for biological analysis and is widely used for identification and quantification of proteins and peptides. Usually, LC-MS is used to provide initial identification based on molecular weight and LC-MS/MS provides further confirmation via structural specific fragmentation. Combination of LC-MS and LC-MS/MS analyses allow sensitive and unambiguous analysis of peptides in complex sample matrices. In this work, LC-MS and LC-MS/MS methods were developed for simultaneous analysis of four Ang peptides in biological samples. The conditions for HPLC separation and MS detections were optimized using a standard mixture of Ang 1-7, Ang II, Ang III, and Ang IV. Quantification used the stable isotope dilution method with 13C515N1-Ang IV as an internal standard. This approach applies the absolute quantification (AQUA) strategy first reported by Gerber et al [19,20]. The methods were evaluated for reproducibility, recovery, and detection limits. A method for solid phase extraction of Ang peptides from biological samples was also developed to improve their recovery. The utility of the method was demonstrated by analyzing Ang II metabolism by bovine adrenal microvascular endothelial cells.

Materials and methods

Materials

Ang 1-7 was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Ang II, Ang III and Ang IV were purchased from BACHEM (King of Prussia, PA, USA). Internal standard 13C515N1-Ang IV was synthesized by the Protein Nucleic Acid Facility of the Medical College of Wisconsin. C18 solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridges (6ml, 500mg) were obtained from Waters Corporation (Milford, MA, USA) and Bond Elut (Varian, Harbor City, CA). All other chemicals and solvents were HPLC grade. Deionized water was used in all experiments.

Ang II metabolism by adrenal endothelial cells

Bovine adrenal microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs) were cultured in alpha MEM with 15% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin and plated in six-well culture plates [18]. Once the cells were 70% confluent, each well was rinsed three times with 2 mL of HEPES buffer (NaCl 130 mM, KCl 5 mM, HEPES 20 mM, CaCl2 1 mM, MgCl2 2 mM and glucose 30 mM; pH 7.4). Ang II (10−7M) was added to each well. HEPES buffer without Ang II was added to wells as the controls. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 0, 5, 15, 30 and 60 min and the supernatant was removed. All samples were extracted and analyzed on the same day of their generation.

Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE)

The 13C515N1-Ang IV internal standard (2.0 ng) was added to the samples and mixed. Then, formic acid was added to the final concentration of 0.5%. The sample solutions were applied to the Waters C18 SPE cartridge that had been preconditioned with 5 ml of ethanol and 15 ml deionized water, respectively. After loading the sample, the cartridge was washed with 3 ml of deionized water. Vacuum was applied to dry the column. This step eliminated water from the elution solvent reducing the time for drying the sample. The angiotensin peptides were eluted from the cartridge using 7 ml methanol containing 5% formic acid. The column eluate was collected and dried under the stream of nitrogen. Finally, the dried sample was redissolved in 30 μl of 16% acetonitrile in water containing 0.1% formic acid and transferred to a sample vial for LC-MS and LC-MS/MS analyses.

LC-MS and LC-MS/MS analyses

All LC-MS and LC-MS/MS experiments were carried out with a Waters-Micromass Quattro micro™ API electrospray triple quadrupole mass spectrometer coupled with a Waters 2695 high performance liquid chromatograph. The mass spectrometer is equipped with a Z-spray dual orthogonal ionization source and is controlled by MassLynx 4.0 software (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA). The samples were separated on a reverse-phase C18 column (Jupiter 2.0 × 250 mm, Phenomenex) using water-acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid as a mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min. All HPLC separations were performed at ambient temperature. The mobile phase gradient of 16% acetonitrile in water, which linearly increased to 38% acetonitrile over 10 min, subsequently, the mobile phase was increased to 100% acetonitrile over 15 min. The positive ion electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrometric conditions were as follows: capillary voltage, 3.5 kV; cone voltage, 15 ~18 V; desolvation temperature, 300°C; desolvation gas flow, 1000 l/h; source temperature, 120°C. LC-MS analysis was performed with the single ion recording (SIR) mode, which the m/z 300.6, 311.8, 349.6, 388.8 and 391.8 were used for Ang 1-7, Ang III, Ang II, Ang IV and internal standard, respectively.

LC-MS/MS was performed with multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) of transitions: m/z 300.6→109.6 (Ang 1-7), m/z 311.3→228.4 (Ang III), m/z 349.6→255.2 (Ang II), m/z 388.8→263.4 (Ang IV), and m/z 391.8→269.2 (internal standard). Argon gas was used as collision gas and the collision energies were set at 27–30 eV.

The calibration curves were constructed over the range of 5 pg to 625 pg for LC-MS and 50 pg to 1250 pg for LC-MS/MS per injection, and the concentrations of the angiotensin peptides in the samples were determined by comparing their ratios of peak areas to the calibration curves.

Results and Discussion

Optimizations of LC-MS and LC-MS/MS conditions

The MS conditions were optimized by monitoring MS signals of standard Ang peptides while varying cone voltage, capillary voltage, extractor voltage, RF lens, source temperature, desolvation temperature and desolvation gas flow rate. Cone voltage was the major parameter influencing the signals. Under different cone voltages, Ang peptides produce (M+H)+, (M+2H)2+ and (M+3H)3+ ions. With low cone voltages (10–15 V), the signals of (M+3H)3+ ions for Ang 1-7, Ang III and Ang II were higher than (M+2H)2+ ions. But, with high cone voltages (20–30 V), the signals of (M+3H)3+ were weaker than (M+2H)2+ ions. In comparison of the signals under different cone voltages, the intensities of (M+3H)3+ ions for Ang 1-7, Ang III and Ang II under low cone voltages (10–15 V) were ten-fold higher than those of (M+2H)2+ ions under high cone voltages (20–30 V). For Ang IV and the internal standard, (M+2H)2+ ions were observed as the highest signals.

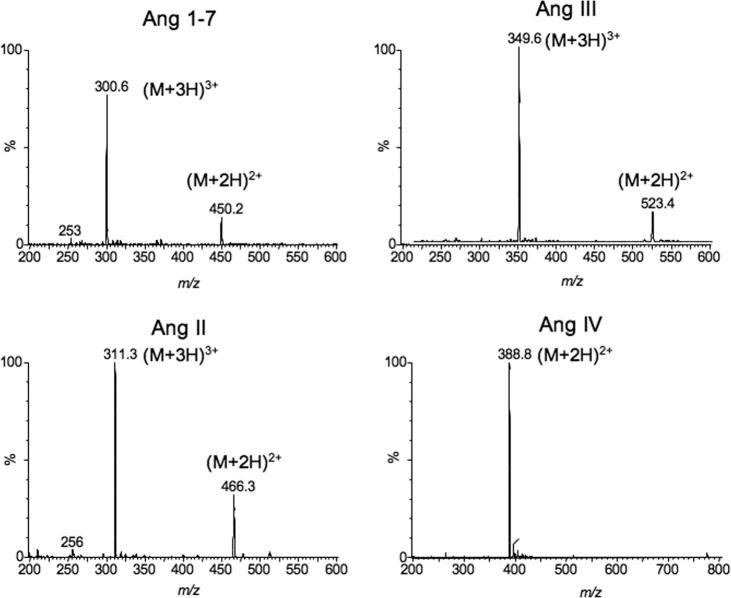

Mass spectra of Ang peptides under low cone voltages, were obtained from LC-MS using a full mass scan mode (from m/z 150 to 1200) (Figure 1). Ang 1-7, Ang III and Ang II show strong (M+3H)3+ signals at m/z 300.6, 311.8 and 349.6, respectively, while Ang IV and internal standard show higher (M+2H)2+ signals at m/z 388.8 and 391.8, respectively. We chose these ions for detection of the peptides in the SIR mode.

Figure 1.

The mass spectra of Ang 1-7, Ang III, Ang II and Ang IV under low cone voltages (10–15 V) by LC-MS.

For the LC-MS/MS method, the collision gas pressure and collision gas voltage were adjusted to get the highest signal of the product ion for each peptide. The collision gas pressure had the greatest effect on the generation of product ions for the peptides, and the intensity of the product ions. When the collision gas pressure was 3.8 ×10−4 mbar, the best signals were obtained for the product ions for all the peptides. After determining the optimal collision gas pressure in the collision cell, the optimal gas voltage for each Ang peptide was determined.

Optimization of Solid-Phase Extraction Conditions

Sample preparation was critically important in the LC-MS analysis of the Ang peptides. All samples were prepared by the solid-phase extraction (SPE) using reversed phase C18 columns. Two different sources of SPE C18 columns (Bond Elut, Varian, Harbor City, CA; Waters, Milford, MA) were tested. Waters’ SPE columns gave higher recoveries for all the Ang peptides than the Varian SPE columns. Methanol, ethanol, isopropanol, acetone and acetonitrile were tested as the elution solvent. Methanol and acetonitrile provided better recoveries than other solvents. The recoveries of Ang peptides with methanol or acetonitrile alone were low, less than 20%. Addition of acids, such as formic acid, acetic acid and trifluoroacetic acid, to the methanol or acetonitrile greatly improved the extraction recoveries. Recoveries of 70 – 90% were achieved when 5% formic acid was added to methanol for elution.

Calibration curves, recoveries and limits of detection (LODs)

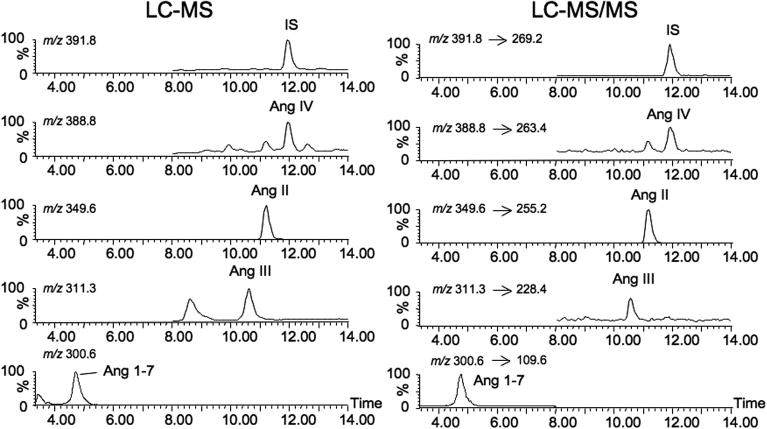

Figure 2 shows LC-MS and LC-MS/MS chromatograms of standard solution of Ang peptides extracted using the SPE protocol, SIR scan mode for LC-MS and MRM mode for LC-MS/MS. For LC-MS, two SIR channels were selected: channel 1, 0–8 min, for Ang 1-7 (m/z = 300.6); channel 2, 8–14 min, for Ang III, Ang II, Ang IV and internal standard (m/z = 311.8, 349.6, 388.8 and 391.8). For LC-MS/MS, two MRM channels were selected: channel 1, 0–8 min, for Ang 1-7 (m/z 300.6→109.6); channel 2, 8–14 min, for Ang III (m/z 311.8→228.4), for Ang II (m/z 349.6→255.2), for Ang IV (m/z 388.8→263.4), and for internal standard (m/z 391.8→269.2).

Figure 2.

LC-MS and LC-MS/MS chromatograms of extracted angiotensin peptides using the SPE protocol, SIR mode for LC-MS (m/z 300.6 for Ang 1-7, m/z 311.8 for Ang III, m/z 349.6 for Ang II, m/z 388.8 for Ang IV and m/z 391.8 for internal standard), and MRM mode for LC-MS/MS (m/z 300.6→109.6 for Ang 1-7, m/z 311.3→228.4 for Ang III, m/z 349.6→255.2 for Ang II, m/z 388.8→263.4 for Ang IV and m/z 391.8→269.2 for internal standard).

The calibration curves of the four peptides were obtained by plotting the peak area ratios of analytes to internal standard as a function of the corresponding amounts of peptides using either LC-MS (Figure 3A) or LC-MS/MS (Figure 3B). The calibration curves for all peptides by LC-MS were linear with R2 values of 0.9987, 0.9934, 0.9961 and 0.9967 for Ang 1-7, Ang III, Ang II and Ang IV, respectively. The calibration curves by LC-MS/MS were linear with R2 values of 0.9981, 0.9988, 0.9998 and 0.9998 for Ang 1-7, Ang III, Ang II and Ang IV, respectively. The calibration curve of Ang IV exhibits a much larger slope compared with those of other peptides, indicating a more sensitive response to Ang IV and leading to a much lower LOD. The LODs for the peptides were determined by measuring the amounts of peptides producing a signal–to-noise ratio of 3 (S/N=3) in SIR mode and MRM mode. The LODs for LC-MS and LC-MS/MS are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. The LODs for the Ang peptides by LC-MS are in low picogram range. A detection limit below 1 pg on column is possible for Ang IV by LC-MS.

Figure 3.

Calibration curves of Ang 1-7, Ang III, Ang II and Ang IV by (A) LC-MS and (B) LC-MS/MS.

Table 1.

LODs (S/N=3) and recoveries (n=6) determined by LC-MS.

| Target analyte | LOD (pg) | Total amount (pg) | Recovery (%) | CV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ang 1-7 | 5 | 50 | 92.5 | 8.9 |

| 500 | 71.2 | 4.0 | ||

| Ang III | 5 | 50 | 85.3 | 5.8 |

| 500 | 80.8 | 7.0 | ||

| Ang II | 5 | 50 | 99.0 | 4.1 |

| 500 | 88.3 | 7.8 | ||

| Ang IV | 1 | 50 | 90.1 | 3.6 |

| 500 | 88.2 | 8.8 |

Table 2.

LODs (S/N=3) and recoveries (n=6) determined by LC-MS/MS.

| Target analyte | LOD (pg) | Total amount (pg) | Recovery (%) | CV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ang 1-7 | 25 | 250 | 82.0 | 5.1 |

| 500 | 84.9 | 6.4 | ||

| Ang III | 25 | 250 | 87.0 | 8.7 |

| 500 | 83.0 | 7.2 | ||

| Ang II | 25 | 250 | 82.8 | 9.2 |

| 500 | 97.0 | 4.2 | ||

| Ang IV | 20 | 250 | 99.0 | 3.0 |

| 500 | 87.7 | 2.4 |

The recoveries of Ang peptides were determined from the SPE of known amount of standards from HEPES buffer and analyzed by LC-MS and LC-MS/MS. Recovery experiments were carried out at two different concentrations. These results were calculated from the extracted Ang peptides as compared to the nonextracted standards. The results for recoveries for LC-MS and LC-MS/MS are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. The recoveries of the Ang peptides ranged between 70% and 99%, with a coefficient of variation (CV) of less than 10%. All the peptides showed reproducible recoveries as indicated by the low standard deviations.

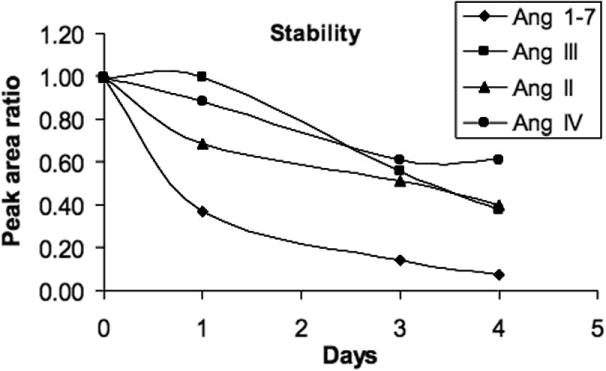

Analyte Stabilities

Figure 4 shows the stability of the Ang peptides in a stock solution (water:acetonitrile = 84:16 with 0.1% formic acid) over four days. The peptides were measured by LC-MS. For all the peptides, a significant decrease of peak areas was observed with storage. The reasons for the disappearance of the peptides are not clear but could be due to binding to container surfaces. Therefore, the use of fresh standards for each analysis time is recommended. Also, the samples must be extracted and analyzed immediately to prevent losses of analytes. In addition, the sample preparation time should be shortened to reduce the loss of the peptides.

Figure 4.

The loss of angiotensin peptides with storage as stock solution water:acetonitrile (84:16) with 0.1% formic acid.

Applications of the LC-MS and LC-MS/MS methods

The LC-MS and LC-MS/MS methods were used to analyze Ang II metabolism in BMECs. Because of the loss of Ang peptides in solution (Figure 4), all BMEC samples were extracted and analyzed immediately. Incubation of BMECs with Ang II (10−7 M) resulted in the formation of varying amounts of Ang 1-7, Ang III and Ang IV. Figure 5 shows the LC-MS and LC-MS/MS chromatograms of Ang 1-7, II, III, IV and the internal standard from the media of BMECs. Although LC-MS was more sensitive for determining these peptides, extra peaks were eliminated by using LC-MS/MS.

Figure 5.

LC-MS and LC-MS/MS chromatograms of Ang 1-7, II, III, IV and internal standard in supernatant samples from bovine adrenal microvascular endothelial cells incubated for 30 min with 10−7M Ang II.

Figure 6 shows the amounts of Ang 1-7, Ang II, Ang III and Ang IV formed by endothelial cells following incubation with Ang II of various times. These results showed that the amount of Ang II decreased with time, while the amounts of Ang 1-7, III and IV increased over time. This indicates that Ang II was metabolized to Ang 1-7, Ang III and Ang IV. The concentration of Ang 1-7 was 5-fold higher than the concentrations of Ang III and IV indicating that Ang 1-7 was the major metabolite of Ang II in BMECs. Blood vessels are an important target for the actions of Ang peptides. Ang II is converted to Ang 1-7 by angiotensin converting enzyme-2 in the endothelial cells [21, 22]. The vascular action of Ang 1-7 is vasodilation; therefore the opposite to Ang II induce vasoconsriction. Ang III is formed from Ang II by aminopeptidase A and participates in the control of blood pressure by the release of aldosterone [23, 24]. Further metabolism of Ang II by aminopeptidase N generates Ang IV which acts by stimulating the AT4 receptor [25–27].

Figure 6.

Concentrations of Ang 1-7, Ang II, Ang III and Ang IV in bovine adrenal microvascular endothelial cells incubated with Ang II (10−7M) for 0, 5, 15, 30, 60 min. Values= mean±S.E. (n=3).

Conclusions

LC-MS and LC-MS/MS methods have been developed for simultaneous analysis of Ang peptides in biologic samples. Comparison of these two methods, LC-MS is more sensitive detecting the peptides to low picogram level. Although less sensitive, LC-MS/MS is more selective and specific than LC/MS. Some interference in biological samples is eliminated by LC-MS/MS. Using these two methods can achieve simultaneous identification and quantification of physiological concentrations of Ang 1-7, Ang III, and Ang II and Ang IV in biological samples. There were some concerns of instabilities of the Ang peptides; however, this was minimized by shortening the time between sampling, extraction and analysis. These methods were applied to determining the metabolism of Ang II by bovine adrenal microvascular endothelial cells. The results showed that Ang II is metabolized by BMECs to Ang 1-7, Ang III and Ang IV with Ang 1-7 was the major metabolite.

In comparison with the radioimmunoassay, MS detection has advantages of simultaneous determination of Ang peptides and correction for recoveries with an internal standard. Also, MS method does not require using hazardous radioactive substances.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Andrea Forgianni for her technical assistance and Ms. Gretchen Barg for her secretarial assistance. The studies were supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (HL-83297). The LC-ESI-MS/MS was provided by an instrumentation grant from the National Institute of Research Resources (RR-17824).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.de Gasparo M, Catt KJ, Inagami T, Wright JW, Unger T. International union of pharmacology. XXIII. The angiotensin II receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:415–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaschina E, Unger T. Angiotensin AT1/AT2 receptors: regulation, signalling and function. Blood Press. 2003;12:70–88. doi: 10.1080/08037050310001057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delafontaine P, Lou H. Angiotensin II regulates insulin-like growth factor I gene expression in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:16866–16870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnes JM, Barnes NM, Costall B, Coughlan J, Kelly ME, Naylor RJ, Tomkins DM, Williams TJ. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition, angiotensin, and cognition. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1992;19(Suppl 6):S63–71. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199219006-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Itoh H, Mukoyama M, Pratt RE, Gibbons GH, Dzau VJ. Multiple autocrine growth factors modulate vascular smooth muscle cell growth response to angiotensin II. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:2268–2274. doi: 10.1172/JCI116454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrario CM. Does angiotensin-(1-7) contribute to cardiac adaptation and preservation of endothelial function in heart failure? Circulation. 2002;105:1523–1525. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000013787.10609.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santos RA, Campagnole-Santos MJ, Andrade SP. Angiotensin-(1-7): an update. Regul Pept. 2000;91:45–62. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(00)00138-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heitsch H, Brovkovych S, Malinski T, Wiemer G. Angiotensin-(1-7)- stimulated nitric oxide and superoxide release from endothelial cells. Hypertension. 2001;37:72–76. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy TJ, Alexander RW, Griendling KK, Runge MS, Bernstein KE. Isolation of a cDNA encoding the vascular type-1 angiotensin II receptor. Nature. 1991;351:233–236. doi: 10.1038/351233a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kambayashi Y, Bardhan S, Takahashi K, Tsuzuki S, Inui H, Hamakubo T, Inagami T. Molecular cloning of a novel angiotensin II receptor isoform involved in phosphotyrosine phosphatase inhibition. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:24543–24546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mukoyama M, Nakajima M, Horiuchi M, Sasamura H, Pratt RE, Dzau VJ. Expression cloning of type 2 angiotensin II receptor reveals a unique class of seven-transmembrane receptors. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:24539–24542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.von Bohlen und Halbach O. Angiotensin IV in the central nervous system. Cell Tissue Res. 2003;311:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00441-002-0655-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reudelhuber TL. The renin-angiotensin system: peptides and enzymes beyond angiotensin II. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2005;14:155–159. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200503000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Silva PE, Husain A, Smeby RR, Khairallah PA. Measurement of immunoreactive angiotensin peptides in rat tissues: some pitfalls in angiotensin II analysis. Anal Biochem. 1988;174:80–87. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90521-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kohara K, Brosnihan KB, Chappell MC, Khosla MC, Ferrario CM. Angiotensin-(1-7). A member of circulating angiotensin peptides. Hypertension. 1991;17:131–138. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.17.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolny A, Clozel JP, Rein J, Mory P, Vogt P, Turino M, Kiowski W, Fischli W. Functional and biochemical analysis of angiotensin II-forming pathways in the human heart. Circ Res. 1997;80:219–227. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohara K, Tabuchi Y, Senanayake P, Brosnihan KB, Ferrario CM. Reassessment of plasma angiotensins measurement: effects of protease inhibitors and sample handling procedures. Peptides. 1991;12:1135–1141. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(91)90070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosolowsky LJ, Hanke CJ, Campbell WB. Adrenal capillary endothelial cells stimulate aldosterone release through a protein that is distinct from endothelin. Endocrinology. 1999;140:4411–4418. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.10.7060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gygi SP, Rist B, Gerber SA, Turecek F, Gelb MH, Aebersold R. Quantitative analysis of complex protein mixtures using isotope-coded affinity tags. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:994–999. doi: 10.1038/13690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirkpatrick DS, Gerber SA, Gygi SP. The absolute quantification strategy: a general procedure for the quantification of proteins and post-translational modifications. Methods. 2005;35:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrario CM. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and angiotensin-(1-7): an evolving story in cardiovascular regulation. Hypertension. 2006;47:515–521. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000196268.08909.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vickers C, Hales P, Kaushik V, Dick L, Gavin J, Tang J, Godbout K, Parsons T, Baronas E, Hsieh F, Acton S, Patane M, Nichols A, Tummino P. Hydrolysis of biological peptides by human angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:14838–14843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200581200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ardaillou R. Active fragments of angiotensin II: enzymatic pathways of synthesis and biological effects. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 1997;6:28–34. doi: 10.1097/00041552-199701000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carrera MP, Ramirez-Exposito MJ, Valenzuela MT, Duenas B, Garcia MJ, Mayas MD, Martinez-Martos JM. Renin-angiotensin system-regulating aminopeptidase activities are modified in the pineal gland of rats with breast cancer induced by N-methyl-nitrosourea. Cancer Invest. 2006;24:149–153. doi: 10.1080/07357900500524389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wright JW, Harding JW. Important role for angiotensin III and IV in the brain renin-angiotensin system. Brain Res Rev. 1997;25:96–124. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamilton TA, Handa RK, Harding JW, Wright JW. A role for the angiotensin IV/AT4 system in mediating natriuresis in the rat. Peptides. 2001;22:935–944. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(01)00405-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farjah M, Washington TL, Roxas BP, Geenen DL, Danziger RS. Dietary NaCl regulates renal aminopeptidase N: relevance to hypertension in the Dahl rat. Hypertension. 2004;43:282–285. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000111584.15095.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]