Abstract

Both simian and human immunodeficiency viruses (SIV and HIV) utilize chemokine receptors, with or with-out CD4, as portals for entry into susceptible cells. In this report, we present the cloning and comparison of 11 rhesus macaque chemokine receptors and receptor-like proteins (CCR1, CCR2b, CCR3, CCR5, CCR8, CXCR4, STRL33, GPR1, GPR15, APJ, and CRAM-A/B), the human counterparts of which have been previously shown to be utilized by SIV for entry.

Rhesus Macaque simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), a lentivirus closely related to human immunodeficiency virus 2 (HIV-2), causes a pathogenic, immunosuppressive disease in these animals that mirrors human AIDS.1 Both viruses have been shown to utilize chemokine receptors as portals for entry into susceptible cells.2–6 However, most of the receptor utilization experiments performed to date have employed human chemokine receptors.2–10 To study the biology of the simian virus with simian receptors instead of with human receptors, we have cloned rhesus macaque counterparts for 11 of these receptors: CCR1, CCR2b, CCR3, CCR5, CCR8, CXCR4, STRL33 (also known as Bonzo, TYMSTR), GPR1, GPR15 (also known as BOB), APJ, and CRAM-A/B (also known as CKRX, CCRL2). The human counterparts of these, save CRAM-A/B, have been shown to function as coreceptors for HIV entry2–10; human CCR5, CCR8, STRL33, GPR1, GPR15, and APJ have also been shown to be utilized by SIVs for entry. 5,7,10

Rhesus macaque CCR1 and CCR5 were cloned from total RNA, isolated by Purescript (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN) from rhesus macaque PBMCs, by RT-PCR; rhesus macaque CCR2b was cloned similarly from rhesus macaque macrophages, as was rhesus macaque CCR3 from rhesus macaque PBLs. All other receptors (i.e., CCR8, STRL33, GPR1, GPR15, APJ, and CRAM-A/B) were cloned by PCR from genomic DNA that was isolated from rhesus macaque PBMCs by proteinase K digestion and hypotonic lysis in 1× Pfu PCR buffer (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Genomic DNA was used as a template in these latter cases because the open reading frames for the human counterparts are coded on unspliced mRNAs.11

For receptors cloned by RT-PCR, 5 µg of total RNA was digested with 1 U of RNase-free DNase (RQ1; Promega, Madison, WI), primed with random hexamers, and reverse transcribed with SuperScript II (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD), all as per manufacturer directions. One-tenth of this cDNA, or 100 ng in the case of genomic DNA, was used in a 50-µl PCR with 400 nM to 1 µM primers (see Table 1), 1.25 U of Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene), and 1.25 U of Amplitaq DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems, Branchburg, NJ). Most reactions were performed with 1× Pfu PCR buffer; some were optimized and then conducted with the OptiPrime PCR kit (Stratagene). Primers were chosen that contained sequences immediately upstream and downstream of the human receptor sequences, to obtain the entire coding region of each rhesus macaque receptor.

TABLE 1.

Primers and enzymes used to clone each rhesus macaque receptor and genbank genetic accession numbersa

| Receptor | Upstream primer | 5′enzyme | Downstream primer | 3′enzyme | Accession No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCR1 | CGGGATCCACCATGGAAACTCCAAACACCACAGAGG | Bam HI | CACGCTCGAGTCAGAACCCAGCAGAGAGTTCATGC | Xho I | AF017282 |

| CCR2b | GCAGGATCCGACGCATTTCCCCAGTACATCC | Bam HI | GGTCCTCGAGCCATGTTTATTCTTCTTGCATTTGGTGGATGC | Xho I | AF013958 |

| CCR3 | GACCAAGCTTCTTCTATCACAGGGAGAAGTG | Hin DIII | CCGCTCGAGCCTCTTTAGGCAATTTTCTGC | Xho I | AF017283 |

| CCR5 | CGGGATCCWYWTTCACAGGGTGGAACAAG | Bam HI | CTCGTCGACATGTGCACAACTCTGACTG | Sal I/Xho I | U96762 |

| CCR8 | CGGGATCCCTTTTATGTGTCTCTGTGACCAGGTCCCGCTGC | Bam HI | GTCCCTCGAGCACTGCTACTAGCATGCCATTC | Xho I | AF100205 |

| CXCR4 | AACTGCAGAACCATAAAGCTTGCCTGAGTGCTCCAGTAGCCACCGCATCTGG | Hin DIII | CAATGCATTGACAGGCTCGAGACATCTGTGTTAGCTGGAGTGAAAACTTGAA | Xho I | U93311 |

| STRL33 | GACGGATCCCCATCCTCAGCCCCAAATATAATTCC | Bam HI | GTCCCTCGAGCAGAGCAGYTTCYCGAAACCCTGGCAAGGC | Xho I | AF124380 |

| GPR1 | GCGGATCCCTTCATTCTCCATTTAGCAAGG | Bam HI | CCTGTCGACACATAAAAAGCCATATACTGATTTGTGG | Sal I/Xho I | AF100204 |

| GPR15 | GCGGATCCAGATTTGGCATCTGCTCTTTGG | Bam HI | CCTGTCGACCAGAGCTTGAAATGTCACAGTTCC | Sal I/Xho I | AF100203 |

| APJ | GCGGATCCTCTGCCCGTCTTCTCTCCACTCCCCAGC | Bam HI | CCTGTCGACAGGGCGCCAGGCTTCTCTCTGCTCC | Sal I/Xho I | AF100206 |

| CRAM-A/B | GTCGGATCCGCTGTCGGAGGGGAAAATCATCTCC | Bam HI | GGTCCTCGAGCCATGTTTATTCTTCTTGCATTTGGTGGATGC | Sal I/Xho I | AF124381 |

Primers were synthesized to match the appropriate human chemokine receptor sequences immediately upstream and downstream of the predicted open reading frame. SalI/XhoI in the column labeled 3′ enzyme indicates that PCR primers contained 5′-terminal SalI sites, but final PCR products were cloned into XhoI sites of pcDNA3.1.

All PCR products were purified (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA), cut with the appropriate restriction enzymes (see Table 1), and cloned directionally into the eukaryotic expression vector pcDNA3.1 (InVitrogen, San Diego, CA). Sequencing was performed by the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions DNA Analysis Facility (Baltimore, MD), and was done on at least three separate clones of each receptor. Accession numbers for these genetic sequences are presented in Table 1.

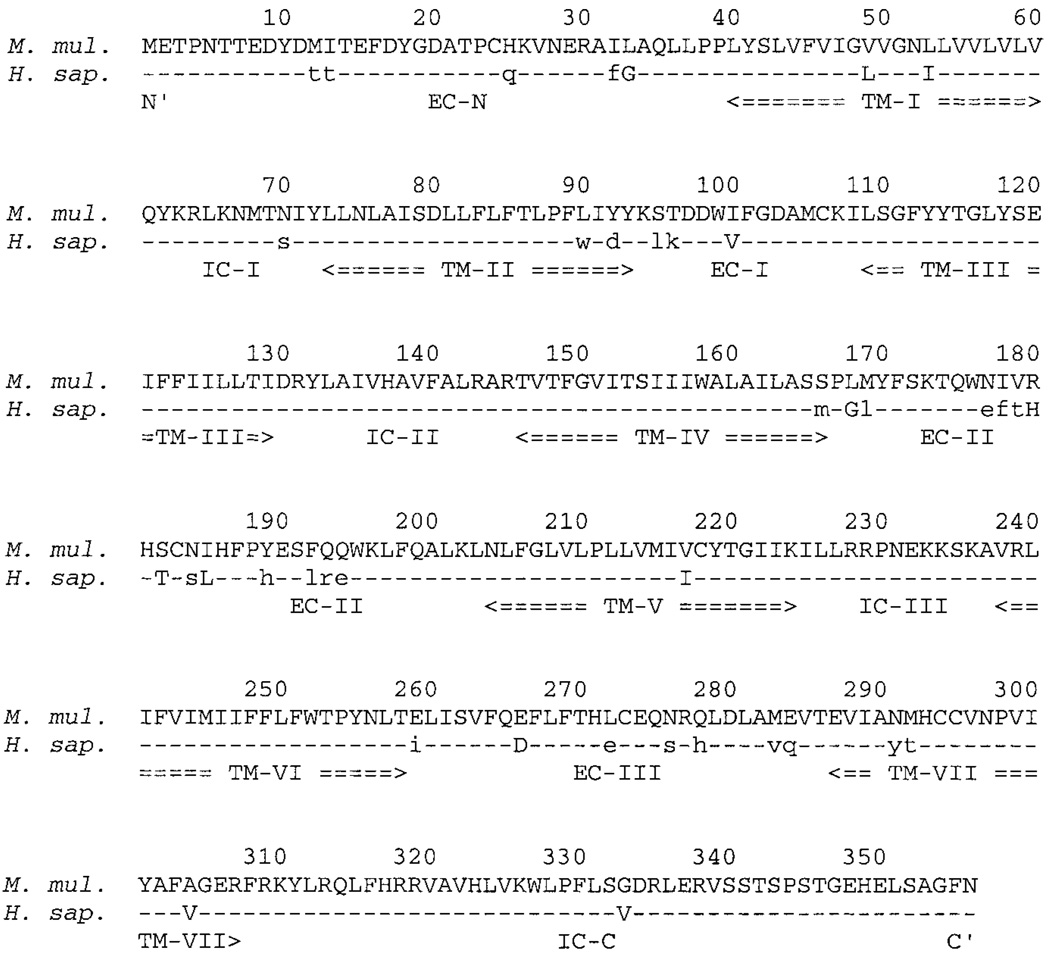

The amino acid sequence of each rhesus macaque receptor was compared with its human counterpart through a CLUSTAL W alignment in MacVector 7.0 for the Macintosh (Genetics Computer Group, Madison, WI). One sample alignment, for the most divergent receptor, CCR1, is displayed in Fig. 1. Invariant amino acids are represented by hyphens, conservatively replaced amino acids are capitalized, and nonconservatively replaced amino acids are presented as lower-case letters. Each amino acid sequence was further analyzed by TopPredII 1.2 (http://www.macinsearch.com/infomac2/science/top-pred-ii-13.html), under default settings for eukaryotes, to determine topology and membrane-spanning regions, as outlined in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Aligned sequences of rhesus macaque CCR1 versus human CCR1 proteins. Upper line in each row is the predicted amino acid sequence of rhesus macaque (M. mul.) CCR1; lower line is predicted amino acid sequence for human (H. sap.) CCR1. Residues that are invariant between both are drawn as hyphens in H. sap. row; conservatively replaced amino acids are displayed in capital letters; all other amino acid differences are shown in lower case. Amino acid residues are numbered from the amino terminus (residue number 1) to the carboxy terminus (residue number 355) above each comparison line. Below each comparison line, the seven putative transmembrane domains are labeled TM-I through TM-VII; putative extracellular domains are labeled EC-N (for amino terminus), then EC-I through EC-III; intracellular domains are labeled IC-I through IC-III, then IC-C (for car-boxy terminus).

As expected, the human and rhesus macaque chemokine receptors analyzed are closely related, especially within the seven predicted membrane-spanning domains (Fig. 1 and Table 2).Differences are scattered throughout each linear amino acid sequence. In most cases, these are single amino acid changes. CCR1, however, displays significant differences between the human and rhesus macaque receptors in the predicted extracellular surface (Fig. 1, residues 1–39, 94–108, 167–203, and 259–286); this is especially distinct in two clusters of completely divergent triplets, at residue numbers 177–179 and 192–194 (Fig. 1), on the predicted second extracellular loop. Hence, although closely related, it appears in the most divergent case of CCR1 that either (1) the CCR1 ligands RANTES, MIP-1α, and/or MCP-1 are quite different in rhesus macaque and human, reflected by a relatively more distant relationship between rhesus macaque and human CCR1; (2) rhesus macaque and human CCR1 have similar but not identical functions in each organism; or (3) variations in the extracellular surface of CCR1 bear no impact on ligand binding and/or activity, assuming that rhesus macaque and human RANTES, MIP-1α, and/or MCP-1 are also similar in sequence and function.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of rhesus and human chemokine receptor similaritya

| Receptor | Similar residues (incl. invariant) (%) | Invariant residues(%) | Similar residues (incl. invariant), Extrac. (%) | Invariant residues, Extrac. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APJ | 378/380(99.5) | 376/380 (98.9) | 95/96 (99.0) | 94/96 (97.9) |

| CXCR4 | 350/352 (99.4) | 346/352 (98.3) | 109/110 (99.1) | 106/110 (96.4) |

| GPR15 | 356/360 (98.9) | 351/360 (97.5) | 90/93 (96.8) | 86/93 (92.5) |

| GPR1 | 351/355 (98.9) | 345/355 (97.2) | 97/98 (99.0) | 96/98 (98.0) |

| CCR5 | 348/352 (98.9) | 341/352 (96.9) | 104/106 (98.1) | 102/106 (96.2) |

| CCR2b | 354/360 (98.3) | 349/360 (96.9) | 102/105 (97.1) | 101/105 (96.2) |

| STRL33 | 332/343 (96.8) | 325/343 (94.8) | 65/74 (87.8) | 63/74 (85.1) |

| CCR8 | 344/356 (96.6) | 336/356 (94.4) | 98/105 (93.3) | 95/105 (90.5) |

| CRAM-A/B | 329/344 (95.6) | 315/344 (91.6) | 101/104 (97.1) | 98/104 (94.2) |

| CCR3 | 338/355 (95.2) | 324/355 (91.3) | 105/117 (89.7) | 94/117 (80.3) |

| CCR1 | 331/355 (93.9) | 316/355 (89.0) | 102/117 (87.2) | 90/117 (76.9) |

Receptors are sorted from most to least similar across entire length of amino acid sequence. Ratio reflects the number of residues that match the given criteria over the total number of residues. Predictions for which regions are extracellular (Extrac.) are based on analysis by TopPredII (see text).

The differences in each pair of human and rhesus macaque receptors, as analyzed by CLUSTAL W and TopPredII, are cataloged in Table 2. The least divergent receptors are rhesus macaque and human APJ, which display only four nonidentical residues (two of which are conservative replacements) in their entire coding regions. CCR1 is the most divergent receptor, exhibiting only 89.0% identity across the open reading frames. In both cases, however, it appears that the predicted extracellular face contains most of the differences between the rhesus macaque and human receptors (e.g., 2 of the 4 nonidentities occur among the 96 extracellular residues of the 380 total residues in APJ). This apparent bias toward the extracellular localization of differences in these receptors occurs for all except CCR3 and CRAM-A/B (Table 2), perhaps reflecting a difference in the three-dimensional conformations these receptors present to potential ligands. The two exceptions, CCR3 and CRAM-A/B, appear to have a more random distribution of differences, potentially indicating that changes extracellularly are less well tolerated in these two receptors.

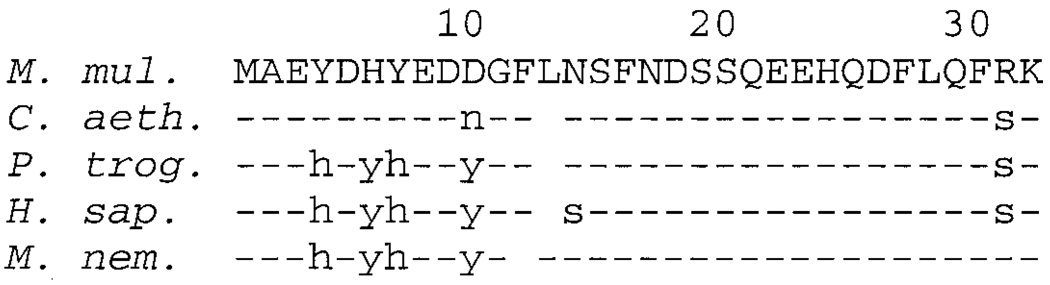

Most of the invariant residues between human and rhesus macaque STRL33 are observed in the aligned linear amino acid sequences at their amino termini (Fig. 2). There are two invariant aspartates at positions 5 and 9 and both have two tyrosines (Fig. 2, positions 4 and 7, in rhesus macaque STRL33, and positions 6 and 10, in human STRL33). The amino termini of chimpanzee STRL33 (P. trog., third row, Fig. 2) and pigtail macaque STRL33 (M. nem., last row, Fig. 2) are much more closely related to that of human STRL33 (H. sap., fourth row, Fig. 2) than to the amino terminus of rhesus macaque STRL33 (M. mul, top row, Fig. 2), and the amino terminus of vervet monkey STRL33 (C. aeth., second row, Fig. 2) is more closely related to the amino terminus of rhesus macaque STRL33 than to that of human STRL33. It has been shown that the amino termini of chemokine receptors are major determinants of specificity of entry for primate immunodeficiency viruses.12–14 Therefore, virus utilization of rhesus macaque versus human STRL33, with respect to the differences in linear sequence versus the apparent similarity in chemical makeup, are currently under investigation.

FIG. 2.

Alignment of the amino-terminal extracellular domains of STRL33 proteins. Species of origin are as follows: rhesus macaque (M. mul.), vervet monkey (C. aeth.), chimpanzee (P. trog.), human (H. sap.), and pigtail macaque (M. nem.). Insertions are represented by spaces; invariant residues with respect to rhesus macaque STRL33 are drawn as hyphens; all other amino acids differences are shown in lower case. Amino acid residues are numbered 1 to 32, from the amino-terminal methionine to the last lysine at the predicted carboxyl end of the amino-terminal extracellular domain.

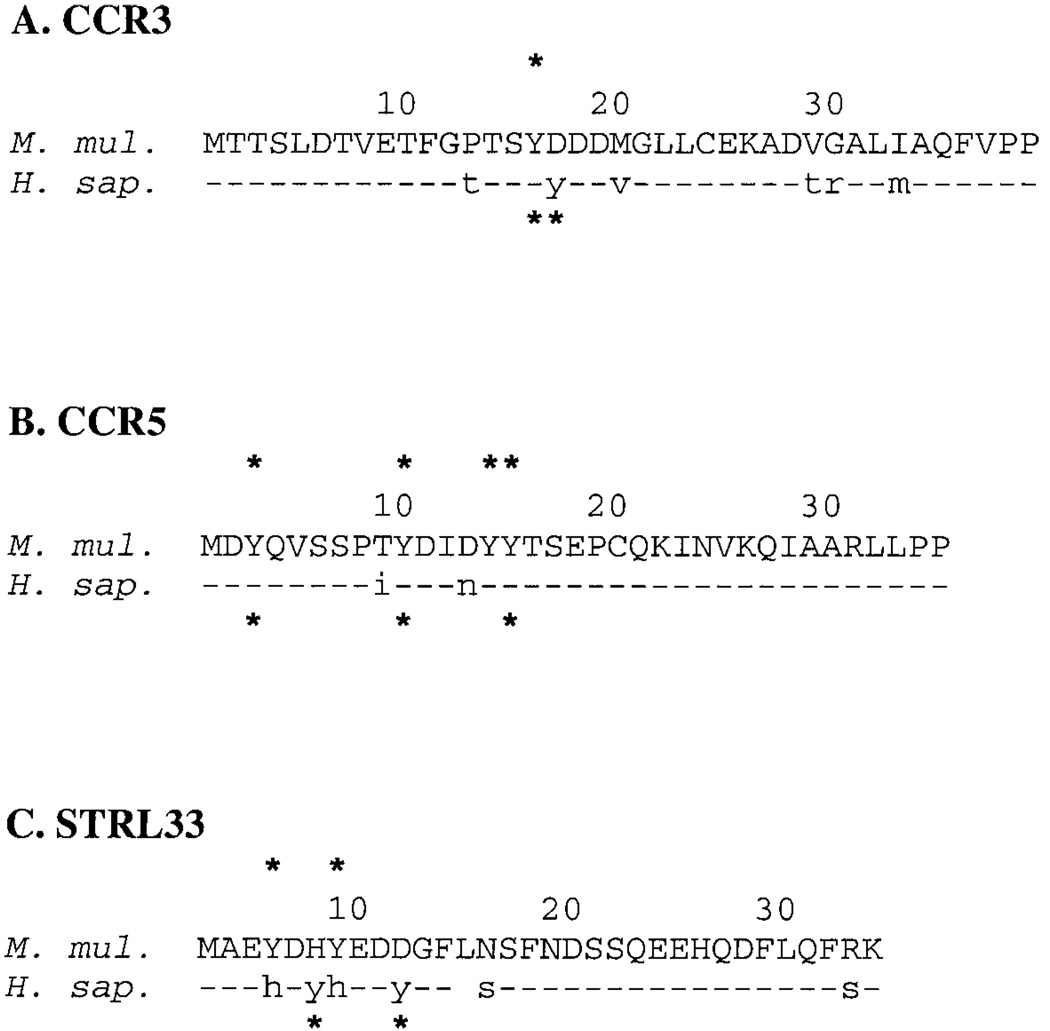

Sulfation of tyrosines in the amino terminus of CCR5 has also been shown to be a determinant of specificity and efficiency of utilization by primate immunodeficiency viruses for binding and entry.14 Of the 11 receptors cloned, only rhesus macaque CCR3, CCR5, and STRL33 show the potential for tyrosine sulfation patterns that differ when compared with the human receptors (Fig. 3). Notably, two of these receptors have been shown to be utilized for SIV infection in vivo (CCR5) and in vitro (CCR5 and STRL33).2,5,7,8 In agreement with previously published work, the sequence we obtained for rhesus macaque CCR5 predicts four sulfated tyrosines at positions 3, 10, 14, and 15 (asterisks, Fig. 3B), as compared with three in human CCR5 (positions 3, 10, and 15); the aspartate-to-asparagine substitution changes residue 13 from acidic to basic, and hence eliminates the ability of the tyrosine at position 14 to be sulfated in human CCR5.15 Addition of a second tyrosine in the amino terminus of human CCR3 (Fig. 3A) adds a second potential substrate for sulfation (as opposed to the single tyrosine in rhesus macaque CCR3; asterisks at residue number 16, Fig. 3A), and, although the amino termini of rhesus macaque and human STRL33 have the same number of potentially sulfated tyrosines (asterisks, Fig. 3C), their linear position is shifted and two amino acids, versus three, separate the sulfated tyrosines in rhesus macaque versus human STRL33. Whether this shifting and varying distance between sulfated tyrosines has an impact on receptor utilization is still unclear.

FIG. 3.

Alignment of extracellular amino-terminal domains of (A) CCR3, (B) CCR5, and (C) STRL33. The rhesus macaque (M. mul.) counterpart is aligned above the human (H. sap.) protein in each alignment. Insertions are represented by spaces; invariant residues between each pair are drawn as hyphens; all other amino acid differences are shown in lower case. Sites of potential tyrosine sulfation are indicated by asterisks. Amino acids are numbered from 1, the amino-terminal methionine, to the last residue at the predicted carboxyl end of the amino-terminal extracellular domain (Pro-39 in CCR3; Pro-35 in CCR5; Lys-32 in STRL33).

We have cloned and sequenced 11 different rhesus macaque chemokine receptors and chemokine receptor homologs. Although their amino acid sequences are similar to those of their human counterparts, there are some potentially important differences that may have effects with respect to their biology in the immune systems of rhesus macaques. More relevant to functional studies of these receptors, we expect that the small number of variations between the rhesus macaque and human receptors can be exploited to evaluate how each receptor is potentially utilized preferentially by simian immunodeficiency viruses over human immunodeficiency viruses for binding and entry.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Karen E. Miller-Stump for work with rhesus macaque CXCR4. B.J.M. is supported by an Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation Scholar Award. This work was supported in part by grants from the U.S. Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, and from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Desrosiers RC. The simian immunodeficiency viruses. Annu Rev Immunol. 1990;8:557–578. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.003013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edinger AL, Clements JE, Doms RW. Chemokine and orphan receptors in HIV-2 and SIV tropism and pathogenesis. Virology. 1999;260:211–221. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marx PA, Chen Z. The function of simian chemokine receptors in the replication of SIV. Semin Immunol. 1998;10:215–223. doi: 10.1006/smim.1998.0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKnight A, Dittmar MT, Moniz-Periera J, et al. A broad range of chemokine receptors are used by primary isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 2 as coreceptors with CD4. J Virol. 1998;72:4065–4071. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4065-4071.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rucker J, Edinger AL, Sharron M, et al. Utilization of chemokine receptors, orphan receptors, and herpesvirus-encoded receptors by diverse human and simian immunodeficiency viruses. J Virol. 1997;71:8999–9007. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.8999-9007.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berger EA, Murphy PM, Farber JM. Chemokine receptors as HIV-1 coreceptors: Roles in viral entry, tropism, and disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:657–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng HK, Unutmaz D, KewalRamani VN, Littman DR. Expression cloning of new receptors used by simian and human immunodeficiency viruses. Nature. 1997;388:296–300. doi: 10.1038/40894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alkhatib G, Liao F, Berger EA, Farber JM, Peden KWC. A new SIV co-receptor, STRL33. Nature. 1997;388:238. doi: 10.1038/40789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffman TL, Stephens EB, Narayan O, Doms RW. HIV type 1 envelope determinants for use of the CCR2b, CCR3, STRL33, and APJ coreceptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11360–11365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choe H, Farzan M, Konkel M, et al. The orphan seven-trans-membrane receptor apj supports the entry of primary T-cell-line-tropic and dualtropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1998;72:6113–6118. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.6113-6118.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy PM. The molecular biology of leukocyte chemoattractant receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:593–633. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.003113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill CM, Kwon D, Jones M, et al. The amino terminus of human CCR5 is required for its function as a receptor for diverse human and simian immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoproteins. Virology. 1998;248:357–371. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edinger AL, Amedee A, Miller K, et al. Differential utilization of CCR5 by macrophage and T cell tropic simian immunodeficiency virus strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4005–4010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farzan M, Mirzabekov T, Kolchinsky P, et al. Tyrosine sulfation of the amino terminus of CCR5 facilitates HIV-1 entry. Cell. 1999;96:667–676. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80577-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bundgaard JR, Vuust J, Rehfeld JF. New consensus features for tyrosine O-sulfation determined by mutational analysis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21700–21705. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.21700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]