Abstract

This review, a sequel to part 1 in the series, collects about 107 chemical entities separated from the roots, leaves and flower buds of Panax ginseng, quinquefolius and notoginseng, and categorizes these entities into about 18 groups based on their structural similarity. The bioactivities of these chemical entities are described. The ‘Yin and Yang’ theory and the fundamentals of the ‘five elements’ applied to the traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) are concisely introduced to help readers understand how ginseng balances the dynamic equilibrium of human physiological processes from the TCM perspectives. This paper concerns the observation and experimental investigation of biological activities of ginseng used in the TCM of past and present cultures. The current biological findings of ginseng and its medical applications are narrated and critically discussed, including 1) its antihyperglycemic effect that may benefit type II diabetics; in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated protection of ginseng on beta-cells and obese diabetic mouse models. The related clinical trial results are stated. 2) its aphrodisiac effect and cardiovascular effect that partially attribute to ginseng’s bioactivity on nitric oxide (NO); 3) its cognitive effect and neuropharmacological effect that are intensively tested in various rat models using purified ginsenosides and show a hope to treat Parkinson’s disease (PD); 4) its uses as an adjuvant or immunotherapeutic agent to enhance immune activity, appetite and life quality of cancer patients during their chemotherapy and radiation. Although the apoptotic effect of ginsenosides, especially Rh2, Rg3 and Compound K, on various tumor cells has been shown via different pathways, their clinical effectiveness remains to be tested. This paper also updates the antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic and immune-stimulatory activities of ginseng, its ingredients and commercial products, as well as common side effects of ginseng mainly due to its overdose, and its pharmacokinetics.

Keywords: Ginseng, ginsenosides, phytomedicine, nitric oxide, diabetics, aphrodisia, neuropharmacology, anti-apoptosis

INTRODUCTION

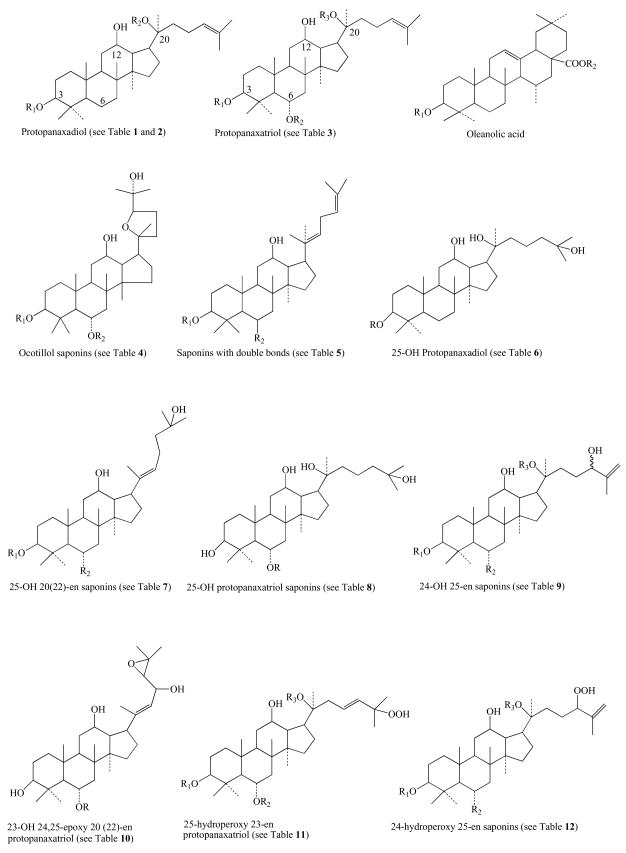

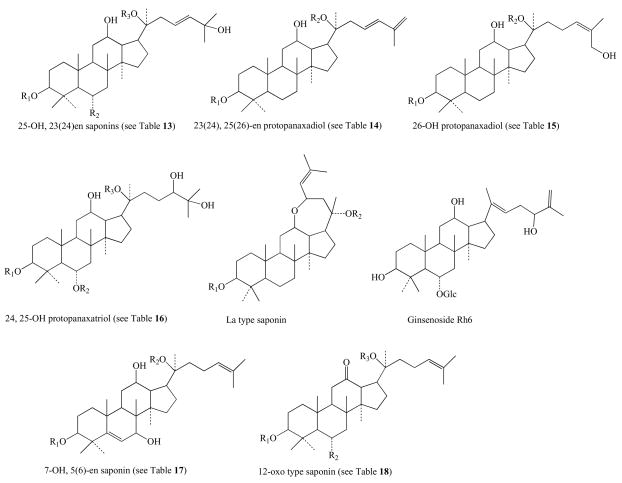

More than two decades ago, Jiang and Xiao first collectively classified 18 chemical entities separated from Panax ginseng into mainly two groups, i.e., protopanaxadiol and protopanaxatriol, along with brief characterization [1]. The mere difference in structures between the two groups is that there are only two hydrogens at the C6 position of protopanaxadiol, whereas, there are glucoses and others linked to the C6 of protopanaxatriol (Fig. 1). The characterization and nomenclature of these ginseng chemical entities undoubtedly facilitated interdisciplinary communications among medicinal chemists, pharmacologists, nutritionists, and clinicians for their understanding of ginseng and its uses in the TCM. With the advent of the internet in 1983 and the invention of the World Wide Web in 1993 by British researcher Tim Berners-Lee, the literature search for published biomedical data in the PubMed and Medline (free services from the U.S. National Library of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health, www.pubmed.gov) has become easier and quicker. The application of high performance liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) to separate and identify new chemical entities at nanomolar concentrations facilitates the discovery work on new chemical entities from ginseng at the pace faster than ever before. As a result of the technology revolution, many new chemical entities from ginseng were exploited by different medicinal and chemical laboratories. There has been no attempt to systematically characterize these chemicals according to their structure-activity relationship (SAR). The systematization on SAR is urgently needed in order to guide future discovery and development in this field to avoid any unnecessary duplication of the same work and waste of resources. This report presents information relating to 107 chemicals obtained mainly from the roots, leaves and flower buds of Panax ginseng, Panax quinquefolius and Panax notoginseng (Fig. 1). These entities are then classified into different groups based on their SAR similarity with brief notes on whether or not each individual molecule possesses bioactivity (Table 1–18). Based on the traditional ‘Yin and Yang’ theory of TCM, we explained the mechanisms of actions of ginseng on balancing body’s physiology and functions with more focus on current biological findings of ginseng’s active ingredients and their pharmacological effects, including the enhancing effect of ginseng on synthesis of nitric oxide, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic and immune-stimulatory activities of ginseng and its ingredients. Various clinical applications of ginseng as a complementary or alternative medicine are also narrated with an emphasis on recent trials for diabetics and cancer (as an adjuvant or immunotherapeutic agent for combined chemotherapy). Pharmacokinetics of ginsenosides and common side effects related to the overdose of ginseng are also discussed.

Fig. 1.

Main structures of ginsenosides.

Table 1.

Structures and Bioactivity of Protopanaxadiol Saponins

| No. | Name | R1 | R2 | Main activity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ra1 | Glc2-Glc | Glc6-Ara (P)4 –Xyl | Not defined | |

| 2 | Ra2 | Glc2-Glc | Glc6-Ara (f)2 –Xyl | Not defined | |

| 3 | Ra3 | Glc2-Glc | Glc6-Glc9-Xyl | Not defined | |

| 4 | Rb1 | Glc2-Glc | Glc6-Glc | Neuroprotective effect; antioxidant Estrogenic effect, | [2, 3] |

| 5 | Rb2 | Glc2-Glc | Glc6-Ara (P) | Inhibitory tumor metastasis | [4] |

| 6 | Rb3 | Glc2-Glc | Glc6-Xyl | inhibit strychnine-sensitive glycine current; pro-oxidative effects | [5, 6] |

| 7 | Rc | Glc2-Glc | Glc6-Ara (f) | Increase immunity; Anti-inflammation | [7, 8] |

| 8 | Rd | Glc2-Glc | Glc | Increase immunity; antioxidant | [5, 6, 8] |

| 9 | Rg3 | Glc2-Glc | H:20(S) | Anti-tumor; Neuroprotective effect; | [9, 10] |

| 10 | Rh2 | Glc | H:20(S) | Anti-tumor | [11, 12] |

| 11 | Ao | Glc2-Glc3- Glc | Glc6-Glc | Not defined | |

| 12 | Rs1 | Glc2-Glc6-Ar | Glc6-Ara (P) | Not defined | |

| 13 | Rs2 | Glc2-Glc6-A | Glc6-Ara (f) | Not defined | |

| 14 | Rs3 | Glc2-Glc6-A | H | Anti-tumor | [13] |

| 15 | F1 | H | Glc | Not defined | |

| 16 | F2 | Glc | Glc | Not defined | |

| 17 | F3 | H | Glc6-Ara (f) | Not defined | |

| 18 | MG-Rb1 | Glc2-Glc6- Ma | Glc6-Glc | Not defined | |

| 19 | MG-Rb2 | Glc2-Glc6- Ma | Glc6-Ara (P) | Not defined | |

| 20 | MG-Rc | Glc2-Glc6- Ma | Glc6-Ara (f) | Not defined | |

| 21 | MG-Rd | Glc2-Glc6- Ma | Glc | Not defined | |

| 22 | R1 | Glc2-Glc6-Ac | Glc6-Glc | Not defined | |

| 23 | NS-R4 | Glc2-Glc | Glc2-Glc6-Glc | Not defined | |

| 24 | NS-Fa | Glc2-Glc2-Xyl | Glc6-Glc | Not defined | |

| 25 | QS-R1 | Glc-Glc-Glc | Glc6-Glc | Not defined | |

| 26 | GyS-XVII | Glc | Glc6-Glc | Not defined | |

| 27 | Ft1 | Glc2-Glc2-Xyl | H | Not defined | [14] |

| 28 | C-Mx | H | Glc6-Xyl | Anti-tumor | [15] |

| 29 | DM1 | H | Glc6-dodecanoyl ester | Anti-tumor | [16] |

| 30 | PM1 | H | Glc6-palmitoyl ester | Anti-tumor | [16] |

| 31 | SM1 | H | Glc6- stearoyl ester | Anti-tumor | [16] |

| 32 | QS-R1 | Glc2-Glc6-A | Glc6-Glc | Not defined | [17] |

| 33 | QS-I | Glc2-Glc6-2-butenoyl | Glc | Not defined | [18] |

| 34 | QS-II | Glc2-Glc6-2-octenoyl | Glc6-Glc | Not defined | [18] |

| 35 | QS-III | Glc2-Glc6-A | Glc | Not defined | [18] |

| 36 | QS-V | Glc2-Glc | Glc6-Glc4-Glc | Not defined | [18] |

| 37 | QS-L5 | Glc2-Glc | Xyl | Not defined | [19] |

| 38 | QS-L10 | Glc | Glc6-Ara (P) | Not defined | [19] |

| 39 | QS-L14 | Glc2-Glc | Ara (P) | Not defined | [19] |

| 40 | NS-Fa | Glc2-Glc2-Xyl | Glc6-Glc | Not defined | [20] |

| 41 | NS-R4 | Glc2-Glc | Glc6-Glc6-Xyl | Not defined | [21] |

Table 18.

Structures and Activity of 12-oxo Saponins

THE THEORY OF TCM AND ITS APPLICATION TO GINSENG’S ACTIONS

The fundamentals of TCM are mainly based on the Yin-Yang and five elements theories. These theories apply the phenomena and laws of nature to the study of physiological activities and pathological changes of the human body and its interrelationships with other external elements. The function of Yin and Yang is guided by the law of unity of the opposites. In other words, Yin and Yang are in conflict but at the same time mutually dependent. The nature of Yin and Yang is relative, with neither being able to exist in isolation. Without “cold” there would be no “hot”; without “moving” there would be no “still”; without “dark” there would be no “light”. The most illustrative example of Yin-Yang interdependence is the interrelationship between substance and function. TCM holds that human life is a physiological process in constant motion and change. Under normal conditions, the waxing and waning of Yin and Yang are kept within certain bounds, reflecting a dynamic equilibrium of the physiological processes. When the balance is broken, disease occurs. Typical cases of disease-related imbalance include excess of Yin, excess of Yang, deficiency of Yin, and deficiency of Yang.

The theory of five elements, i.e., wood, fire, earth, metal and water, was an ancient philosophical concept used to explain the composition and phenomena of the physical universe. In TCM, the theory of five elements is used to interpret the relationship between the physiology and pathology of the human body and the natural environment. The five elements emerged from an observation of the various groups of dynamic processes, functions and characteristics observed in the natural world. The aspects involved in each of the five elements are as follows: fire represents draught, heat, flaring, ascendance, movement, etc.; wood stands for germination, extension, softness, harmony, flexibility, etc.; metal symbolizes strength, firmness, killing, cutting, cleaning up, etc.; earth implies growing, changing, nourishing, producing, etc.; and water symbolizes moisture, cold, descending, flowing, etc. The following table shows categorization of physiological phenomena according to the five elements:

Similar to other traditional medicines, the diagnoses and treatments of diseases by TCM were merely based on personal first-hand observations and empirical reasoning, and therefore, they were subjective. The empirical knowledge of ginseng and its therapeutic potential was passed on by oral preparation. As a result of lack of objective diagnosis standards in ancient times, ginseng’s medical efficacy needs to be re-evaluated and well-verified. It has been difficult to validate some of the medicinal benefits of ginseng using scientifically-sound analysis tools, as there are contradictory results and records of centuries old from different studies with a wide variety of ginseng species that were harvested from different places and then processed, preserved, and extracted differently. These differences could result in differences in ginseng quality and thus differences in its effectiveness.

Nonetheless, Panax ginseng, which is native to China, Korea, and Russia, has been an important herbal remedy in TCM for thousands of years. Ginseng has been traditionally used as a panacea to promote longevity, and as a treatment for weakness and fatigue. It restores the balance between Yin and Yang, stabilizes the dynamic equilibrium of the five elements towards physiological processes, revitalizes and aids recovery from illness.

Ginseng that is produced in the United States and Canada is particularly prized in Chinese societies. According to folk legend, American Ginseng root is more Yin. It is believed to promote Yin energy, clean excess Yang in the body, and restore the dynamic equilibrium of Yin and Yang. According to TCM, for example, diabetes mellitus is defined as Yin deficiency (fatigue, weakness, lethargy, pale complexion), and American ginseng that is believed to promote Yin energy can be used to treat diabetes mellitus [58].

The reason it has been claimed that American ginseng promotes Yin (shadow, cold, negative, female) while East Asian ginseng promotes Yang (sunshine, hot, positive, male) is that, according to traditional Korean medicine, things living in cold places are strong in Yang and vice versa, so that the two are balanced. Chinese/Korean ginseng grows in northeast China and Korea, the coldest area known to many Koreans in traditional times. Thus, ginseng from there is supposed to be very Yang. Originally, American ginseng was imported into China via subtropical Guangzhou, the seaport next to Hong Kong, so folk doctors believed that American ginseng must be good for Yin, because it came from a hot area. However they did not know that American ginseng can only grow in cold regions.

GINSENG COOKERY AND FOLK MEDICINE

Ginseng products are popularly referred to as “tonics,” a term that has been replaced by “adaptogen” in much of the alternative medicine literature. The term “adaptogen” connotes an agent that purportedly increases resistance to physical, chemical, and biological stress and builds up general vitality, including the physical and mental capacity for work. Both American and Panax (Asian) ginseng roots are taken orally as adaptogens, aphrodisiacs, nourishing stimulants, and in the treatment of sexual dysfunction in men.

Many ginseng packages are prominently colored red, white, and blue as a valuable gift. The fresh root, after peeled, can be directly chewed, or soaked in various wines for a period of time before drink and chewing. Ginseng is most often available in dried form, either in whole or sliced form. Ginseng leaf, although not as highly prized, is also used; as with the root it is most often available in dried form. The correct and efficient cooking processes for the dried ginseng are as following: washing the dried roots with running water, immersing the dried roots in boiled water and maintaining the water hot for at least 3 hours or overnight, taking the soaked and hence soft roots out of water and slicing the roots with a knife as small as possible, and finally stewing the sliced roots slowly and gently in the water in a closed vessel before drinking the liquid. Ginseng is usually sliced and simmered in hot water to make a decoction. Ginseng ingredient may also be found in some popular energy drinks, tea varieties, or functional foods. Ginseng root is often sliced and steamed with chicken meat as a soup in China (including Taiwan), and Korea. Usually ginseng is used at subclinical doses for a short period and as such, it does not produce measurable medicinal effects.

CURRENT BIOLOGICAL FINDINGS AND MEDICINAL APPLICATIONS OF GINSENG

Currently ginseng still occupies a prominent position in the herbal best-seller list and is considered the most widely taken herbal product in the world [59]. It is estimated that more than six million Americans are regularly consuming ginseng products. It is mainly used, as it has been for hundreds of years, to increase resistance to physical, chemical and biological stress and boost general vitality. In addition, we have begun to recognize its newly-found activities, including antihyperglycemic effect that may benefit type II diabetics, its modulation to immune system that may serve as an immunotherapeutic agent for combination with chemotherapy (see the late sections). Furthermore, a number of investigations showed antitumor properties and other pharmacological activities of ginseng and its active ingredients, but no trials have confirmed ginseng or ginsenosides as a single agent with significant anticancer activity [60].

The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM; www.nccam.nih.gov), one of the Centers of the National Institutes of Health, USA, is supporting research studies to better understand the use of Asian ginseng, including its interaction with other herbs and drugs, its potential to treat Alzheimer’s disease (PD), and its uses to improve the health of people recovering from illness, increase a sense of well-being and stamina, improve both mental and physical performance, treat erectile dysfunction, hepatitis C, and symptoms related to menopause, and lower blood glucose and control blood pressure. The NCCAM also funds projects to study the effects of American ginseng on colitis and colon cancer associated with colitis.

1. Ginseng and Diabetics

The anti-diabetic drug biguanide metformin is the only approved drug extracted from a herbal source, i.e., French lilac (Galega officinalis). Clinical data are beginning to emerge that support anti-diabetic indications of other herbs, and ginseng is one of the most studied anti-diabetic herbs [61]. Ryu et al. [62] investigated the antioxidant activity of Korean red ginseng and its effect on erectile function in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) rats induced by intraperitoneal injection of 90 mg/kg of streptozotocin on day 2 after birth. According to the diabetic period, the rats were classified as either short-term (22 weeks) or long-term (38 weeks) diabetics. The rats were fed 30 mg/kg of Korean red ginseng three times per week for 1 month. For those rats treated with Korean red ginseng, their erectile function and levels of glutathione (used as an index of the free radical-scavenging activity) [72] and malondialdehyde (an end product of lipid peroxidation used as an index of oxidative stress) were comparable to their age-matched normal controls. In contrast, the untreated diabetic rats showed impaired erectile function and increased levels of glutathione and malondialdehyde. Compound K [23, 24], a major intestinal metabolite of ginsenosides derived from ginseng radix, exhibited anti-hyperglycemic effect through its insulin-secreting action, similar to that of insulin secretagogue sulfonylureas. Treatment of diabetic db/db (db: dependent diabetes) mice (type II diabetic model) for 8 weeks with Compound K (10 mg/kg), or combined with metformin resulted in significant improvements in plasma glucose and insulin levels [63].

A very interesting study showed antihyperglycemic and anti-obese effects of Panax ginseng berry extract and its major constituent, ginsenoside Re, in obese diabetic C57BL/6J ob/ob mice and their lean littermates [64]. The animals received daily intraperitoneal injections of Panax ginseng berry extract for 12 days. On day 12, 150 mg/kg extract–treated ob/ob mice became normoglycemic and had significantly-improved glucose tolerance. The overall glucose excursion during the 2-h intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test decreased by 46% (P< 0.01) compared with vehicle-treated ob/ob mice. The improvement in blood glucose levels in the extract-treated ob/ob mice was associated with a significant reduction in serum insulin levels in fed and fasting mice. A hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp study revealed a significant increase in the rate of insulin-stimulated glucose disposal in treated ob/ob mice. In addition, the extract-treated ob/ob mice lost a significant amount of weight associated with a significant reduction in food intake and a very significant increase in energy expenditure and body temperature. Treatment with the extract also significantly reduced plasma cholesterol levels in ob/ob mice. Additional studies demonstrated that ginsenoside Re plays a significant role in anti-hyperglycemic action. This antidiabetic effect of ginsenoside Re was not associated with body weight changes, suggesting that other constituents in the extract have distinct pharmacological mechanisms on energy metabolism. Ginseng protects cultured beta-cells from apoptosis [65], and also decreases acute postprandial glycemia [66, 67].

Consistent with the above preclinical studies, the following human trials showed some interesting results about effects of ginseng on diabetic patients. Vuksan et al. [68] demonstrated that American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius L) reduced postprandial glycemia in nondiabetic subjects and subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. In addition, Sotaniemi et al. [69] showed that treatment of newly diagnosed NIDDM patients with ginseng (100 or 200 mg) or placebo for 8 weeks elevated mood, improved psychophysical performance, and reduced fasting blood glucose and body weight. The 200-mg dose of ginseng improved glycated hemoglobin, serum PIIINP, and physical activity. Placebo reduced body weight and altered the serum lipid profile but did not alter fasting blood glucose.

Sievenpiper’s study [66] used a randomized, double-blind, multiple-crossover, double-placebo controlled design. Each participant received 10 single-dose treatments in random order: 3 g of ground whole root of American (Panax quinquefolius L.), American-wild (wild Panax quinquefolius L), Asian (Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer), Asian-red (steam treated Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer), Vietnamese-wild (Panax vietnemensis), Siberian (Eleutherococcus senticosus), Japanese-ginseng (Panax Japonicus C.A. Meyer), and Sanchi (Panax notoginseng) ginsengs and two identical placebos. The two placebos were then mixed and treated as one for all comparisons to increase the probability of obtaining a true control for comparisons with the eight ginseng types. The studies showed decreasing, null and increasing effects of the 8 types of ginseng on acute postprandial glycemic indices in healthy humans. The experience with ginseng suggests that although reproducible efficacy may be achieved using an acute postprandial clinical screening model to select an efficacious ginseng batch, dose, and time of administration, there is a need to develop a basis for standardization that ties the composition of herbs to efficacy. In absence of such standardization, the use of herbs in diabetes must be approached cautiously.

2. Aphrodisiac Effect of Ginseng: Involvement of Nitric Oxide

The effects of ginseng on the sexual performance appear to be mediated by the release and/or modification of release of nitric oxide (NO) from endothelial cells and perivascular nerves. NO was named “The Molecule of the Year” in 1992 by the journal Science [70], but it took another 6 years for those who discovered it to win the 1998 Nobel Prize for Physiology and Medicine, including Dr. Robert Furchgott [71]. Together with Dr. Furchgott, we demonstrated the direct relaxation effect of NO on blood vessels [72, 73].

Ginseng has a long reputation in traditional Chinese medicine for treatment of sexual impotence. Recent studies in laboratory animals have shown that both Asian and American forms of ginseng enhance libido and copulatory performance [74, 75]. Indeed, there is good evidence that ginsenosides can facilitate penile erection by directly inducing the vasodilatation and relaxation of penile corpus cavernosum. Treatment with American ginseng also affects the central nervous system and has been shown to significantly alter the activity of hypothalamic catecholamines involved in the facilitation of copulatory behavior and hormone secretion [76]. Consistently with these findings, Choi et al. [77] confirmed in a clinical study the efficacy of Korean red ginseng for erectile dysfunction in 30 patients. In 2002, another double-blind, crossover study of Korean red ginseng’s effects on impotence reported that ginseng can be an effective alternative for treating male erectile dysfunction [78].

The effect of ginseng on the sexual performance may partially be due to changes in hormone secretion, and partially to its (or ginsenosides’) effects on the central nervous system, gonadal tissues, and production of NO. Panax ginseng produced a dose-related increase in serum testosterone levels and American ginseng reduced the plasma level of prolactin hormone in rats [79]. Testosterone might mediate the heightened copulatory behavior in ginseng-treated animals, while prolactin altered it. These results suggest that both ginseng species may have direct actions on the anterior pituitary gland and/or on the hypothalamic dopaminergic mechanisms [75]. Recent findings that ginseng treatment decreased prolactin secretion also suggested a direct nitric oxide-mediated effect of ginseng at the level of the anterior pituitary [75]. Thus, animal studies lend growing support for the use of ginseng in the treatment of sexual dysfunction and provide increasing evidence for a role of nitric oxide in the mechanism of ginsenoside action. Several recent studies have suggested that the antioxidant and organ-protective actions of ginseng are linked to enhance NO synthesis in endothelium of lung, heart, and kidney and in the corpus cavernosum [76, 80]. Enhanced production and function of NO synthase by ginseng thus could contribute to ginseng-associated vasodilatation and perhaps also to an aphrodisiac action of the root. Ginsenoside Re was demonstrated [81] to release NO via a membrane sex steroid receptors resulting in K(Ca) channel activation in vascular smooth muscle cells and promoting vasodilation. Korean ginseng is well known as a treatment for sexual dysfunction [82] because of its ‘Yang’ effect as mentioned above. Korean red ginseng is usually not peeled, but steamed, or heated, and subsequently dried. As a consequence, the process causes an increase in saponin content [82]. Traditionally red ginseng has been used to restore and enhance normal well-being, and is often referred to as an adaptogenic. Kim et al. [83] recently showed that water extract of Korean red ginseng (1–20 mg/ml) produced relaxation response up to 85% in isolated female rabbit vaginal tissue in a dose-dependent manner. Similarly, Choi et al. [84] used male rabbit cavernosal muscle strips (precontracted with phenylephrine) to investigate effect of Korean red ginseng on penile erectile tissue and erectile response. After 3 months of oral administration of 50 mg/kg of Korean red ginseng to both rabbits and rats, relaxation effects were significant as measured in both the male rabbit cavernosal muscle strips and the cavernosal pressures after the stimulation of pelvic nerves innervating rat corpus cavernosum. These effects might be mediated partly through the NO pathway and hyperpolarization via Ca(2+)-activated K(+) channels, or mediated by endothelium-derived relaxing factor (EDRF, which was later demonstrated to be NO [71]) and peripheral neurophysiologic enhancement.

3. Cardiovascular Effects of Ginseng: Involvement of Nitric Oxide

Ginseng has been shown to produce a number of actions on the cardiovascular system. Intravenous administration of ginseng to anesthetized dogs resulted in reduction, followed by an increase in blood pressure, and transient vasodilatation [85]. Recent studies found close relationship between ginseng’s effects and NO production pathway, including regulation of cGMP and cAMP levels [76]. For instance, in rats and rabbits, Lei and Chiou [86] and Kim et al. [87] found that extracts of Panax notoginseng decreased systemic blood pressure and ginsenosides exerted relaxing effects in rings of rat and rabbit aorta, respectively. This relaxing effect of ginseng and its active constituents on the cardiovascular system is partially due to the release of endothelial NO. Researchers have reported that chronic feeding of rabbits with ginsenosides may enhance indirectly vasodilatation by preventing NO degradation by oxygen radicals such as superoxide anions [88]. Ginsenosides have depressant action on cardiomyocyte contraction which may be mediated, in part, through increased NO production [89]. Korean red ginseng can improve the vascular endothelial dysfunction in patients with hypertension possibly through increasing NO [90]. In addition to endothelium-derived NO release, Li et al. [91] reported that ginsenoside-induced vasorelaxation involves Ca2+ activated K+ channels in vascular smooth muscle cells. It has also been reported that crude saponin fractions from Korean red ginseng enhanced cerebral blood flow in rats [92] and ginsenosides reduced plasma cholesterol levels and the formation of atheroma in the aorta of rabbits fed on a high cholesterol diet [88]. This antiatherosclerotic action of ginseng components is apparently due to the correction in the balance between prostacyclin and thromboxane [93], inhibition of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) release, and adrenaline and thrombin-induced aggregation of platelets [94], regulation of cGMP and cAMP levels, and prolongation of the time interval between conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin [95]. Also, ginsenosides have been shown to be relatively potent platelet activating factor antagonists [96].

In parallel with these findings, Nakajima et al. [97] concluded that red ginseng was found to promote the proliferation of vascular endothelial cells, to inhibit the production of endothelin (that is known to constrict blood vessels and result in raising blood pressure), and to increase the production of IL-1β, which suppresses the formation of thrombin in blood coagulation. In the same direction, Yuan et al. [98] used cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells to conclude that panax quinquefolium extracts significantly decreased endothelin (an NO antagonist) concentration in a dose and time dependent manner after thrombin treatment. The role of ginseng in angiogenesis has also been reported. For instance, Kim et al. [99] demonstrated that water extract of Korean red ginseng stimulated in vitro and in vivo angiogenesis via activation of phosphorylation of ERK1/2, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (Akt), and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) resulting in an increase in NO production [99]. Ginsenoside Rg1 promoted functional neovascularization into a polymer scaffold in vivo and tubulogenesis by endothelial cells in vitro [100]. Therefore, ginsenoside Rg1 might be useful in wound healing as it can induce therapeutic angiogenesis.

4. Cognitive Effects of Ginseng

The use of herbal medicine, particularly ginseng to improve cognitive performance has become increasingly popular during recent years and some studies have shown its enhancing effect on learning and memory either in aged and/or brain damaged rodents [101, 102]. For example, significant improvement in learning and memory has been observed in aged and brain-damaged rats after administration of ginseng active ingredients [103–105]. In humans, ginseng or ginseng extract showed significant effects on neurological and psychiatric symptoms in aged humans and psychomotor functions in healthy subjects [106, 107]. This positive effect of ginseng on cognition performance is due to the direct action of ginseng on the hippocampus [108]. Consistent with the study, Wen et al. [109] demonstrated that red ginseng, ginseng powder, and ginsenoside Rb1 administration for seven days prior to ischemia rescued the hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons and subsequently ameliorated learning deficits in gerbils. The influence of ginsenoside Rg1 on the proliferating ability of neuronal progenitor cells may serve as an important mechanism underlying its nootropic and antiaging effects particularly on learning and memory [110].

On the other hand, Persson et al. [111] recruited 3500 community-dwelling volunteers to investigate whether the use of ginseng or ginkgo biloba for a long period of time (up to 2 years) has positive effects on performance on learning and memory. They found that the use of neither ginkgo biloba (n=40) nor ginseng (n=86) was associated with enhanced memory performance in any of the eight memory tests examined, relative to control groups either using or not using nutritional supplements. The study did not provide any quantifiable beneficial effects of ginseng on memory performance. This result coincides with the finding of Sorensen and Sonne [112] who reported that ginseng intake did not enhance memory functions. The investigators admitted, however, that ‘the study lacked direct control of dosage and specificity of formulas used such as measure of daily or weekly intake and the specific brands that were used’. In our view, as stated in our previous paper [113], many factors may cause variation in pharmacological effects of ginseng: the ginsenoside content varies with different Panax species; other factors can also change the quality of ginseng’s products, including growing conditions such as soil conditions, sunlight, rainfall, temperature, time of harvest, age and life cycle stage of ginseng at harvest, time of year when it is harvest, method of drying, storage conditions and duration of storage, processing procedures, the plant age, the part of the plant, and the extraction method. All these can result in deviation in amount of active ingredients of ginseng and the related pharmacological effects.

5. Neuropharmacology of Ginseng and Its Role in Parkinson’s Disease Models

Recently, it has been shown that ginseng and its components, ginsenosides, have a wide range of actions in the central nervous system [114]. These effects include protective effects of ginsenosides against homocysteine-induced excitotoxicity [115], increased cell survival, extension of neurite growth, and rescuing of neurons from death in consequence of different insults either in vivo or in vitro. Ginseng roots appeared to be able to facilitate survival and neurite extension of cultured cortical neurons [116–118], and ginsenosides Rb1 and Rg3 protected neurons from glutamate-induced neurotoxicity [119]. Following forebrain ischemia in gerbils, Wen et al. [109] demonstrated that central infusion of ginsenoside Rb1 rescued the hippocampal CA1 neurons against lethal damage of cellular hypoxia.

Using a spinal neuron model, ginsenosides Rb1 and Rg1 proved to be potentially effective therapeutic agents for spinal cord injuries as they protected spinal neurons from excitotoxicity induced by glutamate and kainic acid and oxidative stress induced by hydrogen peroxide [120]. The most recent studies further confirmed that Rg1 and Rb1 could enhance glutamate exocytosis and release in rat nerve terminals through affecting vesicle mobilization and activation of protein kinase A and/or C, respectively, resulting in an increase in synaptic vesicle availability [121, 122].

A number of studies have recently described the beneficial effect of ginseng and its main components, ginsenosides, on some neurodegenerative disease models. Special interest has been paid to Parkinson’s disease (PD) models either in vivo or in vitro. Geographic variations in PD prevalence might reflect ginseng consumption, as in North America PD occurs in approximately 200 cases per 100,000 persons compared to only 44 cases per 100,000 in China [123]. In an in vivo model, Van Kampen et al. [124] reported that prolonged oral administration of ginseng extract G115 significantly protected against neurotoxic effects of parkinsonism inducing agents such as 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) and its active metabolite 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+) in rodents. The authors found that ginseng-treated animals sustained less damage and TH+ neuronal loss in substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) after MPP+ exposure. Likewise, reduction of TH immunoreactivity in the striatum was effectively diminished as a result of ginseng treatment compared to MPP+-exposed animals. Similarly, striatal dopamine transporter (DAT) was significantly preserved due to ginseng treatment. In vitro studies showed that ginseng saponins enhanced neurite growth of dopaminergic SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cells [125].

Although the processes and mechanisms underlying the neuroprotective effects of ginseng upon dopaminergic neurons remain to be elucidated, several reports demonstrated the inhibition of ginseng on MPP+ uptake in dopaminergic neurons, the suppression of oxidative stress induced by auto-oxidation of dopamine, the attenuation of MPP+-induced apoptosis, and the potentiation of nerve growth factor (NGF). It has been shown that certain ginsenosides inhibit dopamine uptake into rat synaptosomes, and consequently, provide protection against MPP+ through blockade of its uptake by dopaminergic neurons [124]. Ginsenoside Rg1 was shown to interrupt dopamine-induced elevation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) or NO generation in pheochromocytoma cells (PC12). Ginseng radix attenuated MPP+-induced apoptosis as it decreased the intensity of MPP+-induced DNA laddering in PC12 cells and ginsenoside Rg1 had protective effects against MPTP-induced apoptosis in the mouse substantia nigra. These anti-apoptotic effects of ginseng may be attributed to the enhanced expression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl, reduced expression of bax and nitric oxide synthase (NOS), and inhibited activation of caspase-3. Ginseng may also reverse the neurotoxic effects of MPP+ through elevation of NGF mRNA expression [124]. In accordance, ginsenosides Rb1 and Rg1 elevated NGF mRNA expression in rat brain and potentiated NGF-induced neurite outgrowth in cell culture. Furthermore, it has been reported that ginsenosides Rb1, Rg1, Rc, and Re inhibited tyrosine hydroxylase activity and exhibited anti-dopaminergic action since they reduced the availability of dopamine at presynaptic dopamine receptors [126]. Ginseng and its components prevent neuronal loss in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis models, and Ginseng radix has also been used for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease.

In addition to interactions of ginseng with the opioid systems, recent reports have demonstrated that the Korean ginseng product (ginseng total san, also called GTS) attenuates cocaine- or amphetamine-induced behavioral activity such as hyperactivity and conditioned place preference [126]. Using real-time measurements of the extracellular DA concentrations in slices of rat brain nucleus accumbens, Nah et al. [127] showed the ginseng total san attenuated both the release enhancement and the rebound increase during cocaine application and withdrawal, respectively.

6. Ginseng and Cancer

Laboratory studies have been confirming the data obtained from long-term observation on anticancer activity of many herbs. The following herbs have been used for anti-cancer treatment, and some of them are antiangiogenic through multiple interdependent processes including their effects on gene expression, signal processing, and enzyme activities [128]:

Tripterygium wilfordii [129], Artemisia annua (Chinese wormwood), Viscum album (European mistletoe), Curcuma longa (turmeric), Scutellaria barbata (also called Chinese skullcap) [130, 131], resveratrol and proanthocyanidin (grape seed extract), Magnolia officinalis (Chinese magnolia tree), Camellia sinensis (green tea), Ginkgo biloba, quercetin, Poria cocos, Zingiber officinale (ginger), Rabdosia rubescens (rabdosia), and recently Gossypium hirsutum L [132], and Panax ginseng [133, 134].

To date, clinical research results on ginseng are not conclusive enough to prove health claims associated with the herb and only a handful of large clinical trials on ginseng have been conducted. Some claims for health benefits are based only on studies conducted in animals [133]. Although there is no conclusive evidence that ginseng itself can cure cancer, it makes sense that use of ginseng for cancer therapy should focus on synergistic combinations [135]. During active cancer therapy, ginseng should generally be evaluated in combination with chemotherapy and radiation. In this role, it acts as biological response modifiers and adaptogens to synergistically enhance efficacy of the conventional therapy [134]. It can improve immune system activity of patients and their appetite, and functions as a supplementary agent of chemotherapy. For instance, Xing et al. [144] treated 35 rectal cancer patients with retention enema containing 85% ginsenoside for 4–6 h per day for 6–8 consecutive days before surgical operation. The control group (n=15) received retention enema containing saline in the same way. They reported that after ginsenoside treatment symptoms such as frequent defecation, hematochezia and tenesmus were palliated in most patients (25 out of 35), and abdominal pain was relieved in 7 patients with incomplete intestinal obstruction. Electron microscopic examination showed apoptosis in 23 treated patients. In comparison, the above-mentioned changes were not observed in the control group. Preclinical studies have showed some immune-stimulating activity of ginseng and ginsenosides [136].

The recent studies have shown effects of ginsenosides on angiogenesis under many pathological conditions including tumor progression and cardiovascular dysfunctions [137]. Angiogenesis in human body is regulated by two counteracting factors, angiogenic stimulators and inhibitors. Intriguingly, existing literature reports both wound-healing and antitumor effects of ginseng extract through opposing activities on the vascular system. The ‘Yin and Yang’ action of ginseng on angiomodulation is evidenced in parallel by the experimental data showing that the angiogenic effects of ginseng may be related to the compositional ratio of ginsenoside Rg1 to Rb1 [138]. Rb1 inhibits the earliest steps of angiogenesis and chemoinvasion of endothelial cells. By contrast, Rg1 promotes functional neovascularization in vivo, and endothelial proliferation, chemoinvasion and tubulogenesis in vitro, as well as the effects mediated through expression of nitric oxide synthase and phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase→Akt pathway. In addition, the anti-tumor and anti-angiogenic effects of ginsenosides (e.g. Rg3 and Rh2) have been demonstrated in various models of tumor and endothelial cells, indicating that different ginsenosides may have opposing activities in regulating the ‘Yin and Yang’ balance [139]. Chronic inflammation is associated with a high cancer risk. Ginseng’s anti-inflammatory effect may help to prevent the progression of reactive oxygen species (ROS) related inflammation to cancer sequence [140].

Recent in vitro experimental studies have showed anti-cancer effects of various ginsenosides which will be narrated below. However, we have to point out that these in vitro studies, although inexpensive to carry out, should only serve as an adequate screening mechanism, or help us understand the mechanisms of actions of ginsenosides. In addition, the concentrations of ginsenosides applied in some in vitro experiments are as high as 100 μM level in order to produce some biological effects. This fact suggests that the observed biological effects of ginsenosides be non-specific to a particular pathway. Therefore, we propose that when a difference arises between in vitro and in vivo findings, the in vivo results should always take precedence over in vitro studies.

Among those new and old entities listed in Tables 1–18, Zhao et al. [141] recently characterized a new chemical entity 20(S)-25-methoxyl-dammarane-3beta, 12beta, 20-triol, and found that this molecule exhibits apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in the G1 phase of many cancer cell lines including breast and prostate cancer lines at IC50 of low micromolar levels [142]. Recently it has been shown that American ginseng can both prevent and treat mouse colitis [143], which is associated with a high colon cancer risk.

Ginsenosides could specifically induce apoptosis in HL-60 cells. The results provide an experimental basis for treating leukemia with ginsenosides as a supplementary agent in chemotherapy [144]. Some ginsenosides have the effects to induce apoptosis in rectal cancer patients [145]. Ginsenoside Rh2 induced apoptosis in various tumor cells by different pathways. Rh2 interfered with B-cell lymphocyte/leukemia-2 (Bcl-2) family proteins related apoptosis and activated protein kinase Caspase-3 to cause cell apoptosis [146, 147]. Rh2 induced apoptosis of rat C6Bu-1 glioma cells and human SK-N-BE(2) neuroblastoma cells through protein kinase C pathway [148]. Ginsenoside Rh2 also induced apoptosis in human malignant melanoma, which was partially dependent on caspase-8 and caspase-3 [149]. Ginsenoside Rh2 induced apoptosis and inhibited cell growth in C6 glioma cells, human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells, and various ovarian cancer cell lines [150–152]. Mediating G1 growth arrest and apoptosis in human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells appeared to be the molecular mechanisms of ginsenoside Rh2 [150]. Rh2 inhibited human hepatoma Bel-7404 cell lines via arresting cell cycle, up-regulating Bax protein expression and down-regulating mutated p53 protein expression [153]. Rh2 inhibited the growth of MCF-7 cells by inducing p21 protein expression and reducing cyclin D levels. As a result, cyclin/Cdk complex kinase activity, pRb phosphorylation, and E2F release could be inhibited [154].

Rg3 is one of the most effective cytostasis ginsenosides separated from ginseng. Rg3 inhibits human prostate cancer cells and other androgen dependent cells from proliferating [155]. The mechanisms of actions of Rg3 include (1) decreasing genetic expression of 5α-reductase; (2) inhibiting cell cycle evolution genes such as proliferating cell nuclear antigen gene and cell cycle protease D1 gene that would stop cells from proliferating; (3) increasing cyclinase suppressor gene such as p21and p27 so as to make cells settle down at G1 stage; (4) down-regulating Bcl-2 (the anti-induction apoptosis gene); and (5) activating caspase-3 (the induction apoptosis gene) to induce the cells to delete. Rg3 inhibited tumor cell proliferation and induced cell apoptosis in mice with induced liver cancer [156]. In addition, Rg3 can affect the differential expression of cell signaling genes and other related genes in human lung adenocarcinoma cell line A549, and induce apoptosis in the A549 tumor cells and HUVEC 304 cell lines. It was showed that Rg3 and Rg5 had significant inhibition on benzo(a)pyrene-induced adenocarcinoma [157], and dimethylbenz(a)anthracene-induced lung tumor in mice [133]. The ginsenosides had strong inhibitory effects on the development of rat mammary adenocarcinoma induced by methyl-N-nitrosourea and N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea administration, as well as on DMBA-induced uterine and vaginal tumors [158]. Using athymic mice transplanted with ovarian SKOV-3 cancer cells, Xu et al. [159] showed that intraperitoneal injection of ginsenoside Rg3 alone, or Rg3 combined with cyclophosphamide to the mice for 10 days improved life quality and survival of the mice, and reduced tumor weight in the mice in comparison to the control untreated mice. Chen et al. [160] reported that Rg3 produced apoptosis in human bladder transitional cell carcinoma cell line EJ at IC50 125.5 μg/ml after 48 h of incubation. When treated with 150 μg/ml of Rg3 for 24 h and 48 h, the cells showed significant DNA ladders and apoptotic morphological characteristics including the condensed chromatin, the nuclear fragmentation, the apoptotic body and bright fluorescent granules as well as a higher caspase-3 expression. When the cells were treated with 75 μg/ml of Rg3 for 24 h and 48 h, or 150 μg/ml of Rg3 for 48 h, the percentage of cells in S phase and G2/M phase was increased, whereas the percentage of cells in G0-G1 was decreased.

Another ginsenoside, i.e., Compound K (or IH901), was shown to induce apoptosis in human hepatoblastoma HepG2 cells [161], and KMS-11 cells [162] through a cytochrome C-mediated activation of caspase-3 and caspase-8 proteases and inhibition of the fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) expression [163]. Incubation of archeo-marrow leukemic cells HL260 with Compound-K produced apoptosis in the cells in a concentration- and time-dependent manner with morphous changes in chromatic agglutination, atrophy, and nuclear fragmentation [164]. Compound-K suppressed melanoma cell proliferation in BI6-BL6 mice by activating the protein kinase caspase-3 and releasing cytochrome C in mitochondria into cytoplasm [165]. Western blot test revealed that Compound-K could elevate p27Kipl expression, degrade expression of c-Myc and cyclin D1, and induce cell LLC apoptosis through activating caspase-3 protein kinase at the same time [166]. Recently, IH-901 has been reported to induce both G1 arrest and apoptosis, and the apoptosis could be inhibited by COX-2 induction [167].

Ginsenoside Rg1 [27] has been reported to induce the apoptosis of melanoma cells implanted in mice. Inducing morphological change of the tumor cells seems to be the main mechanism of Rg1. Wakabayashi et al. reported ginsenoside M, the intestinal bacterium metabolite of protopanoxadiol saponins, could induce apoptosis in melanoma cell B16-BL6 through up-regulating the expression p27kipl and down-regulating the expression of gene c-myc that promotes cell proliferation [168, 169].

Park et al. [170] discovered that ginsenosides Rg3, Rg5, Rk1, Rs5 and Rs4 were toxic to the human hepatoma carcinoma cell Sk-Hep-1. Rg5 and Rs4 could induce apoptosis by selectively elevating protein levels of p53 and p21WAF (the inhibitor of periodicity-replying protein kinase) and down-regulating the activity of protein kinase in cell cycle E and A, [171].

PHARMACOKINETICS AND OVERDOSE-RELATED SIDE EFFECTS OF GINSENG

Pharmacokinetic studies of ginseng can not be directly conducted using the commonly-used analytical methods that we described [113, 172] because each ginseng specie contains various active ingredients in their roots, and the amount of each ingredient varies with different conditions. All these make it more complex and even impossible to directly conduct pharmacokinetics of ginseng itself. The practical way, however, to conduct ginseng’s pharmacokinetics is to measure individual ginsenoside’s absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination in animals and human beings. Pharmacokinetic studies conducted in rats revealed only 23% absorption of ginsenosides (Rb1) after a period of 2.5 h [173]. Very small recoveries of these ginsenosides were made in the liver (e.g., 0.25% dose) and heart (<0.1% dose), while the majority of the material was recovered in the small intestine. The bioavailability of bioactive ginseng constituents appears very limited, as evidenced by the low absorption rates for orally administered Rg1 (0.1% dose) and Rg2 (1.9% dose), and only little of the original ginsenoside material was recovered in the feces (<1% dose) [174]. In our view, people should not be surprised about the limited amount of ginsenosides recovered from tissues, urine, and feces in the ginseng’s pharmacokinetic studies because the total content of ginsenosides (saponins) in a ginseng is usually less than 5% of its weight [113]. Moreover, ginsenosides have poor oral bioavailability as demonstrated above mainly because of their extensive pre-systemic metabolism and poor membrane permeability. Ginseng has been used for treatment of hyperglycemia and insulin resistance, a common side effect of some HIV-1 protease inhibitors indinavir. In healthy volunteers, co-administration of indinavir 800 mg and American ginseng 1 g per 8 h for 14 days did not change the area-under the plasma-concentration-time curve of the HIV drug compared to indinavir alone (n = 13). Therefore, it was concluded that ginseng does not significantly affect indinavir’s pharmacokinetics [175].

In general, ginseng has a good safety record. The common adaptogenic ginsengs (Panax ginseng and Panax quinquefolia) are generally considered to be relatively safe even in large amounts. To many people, ginseng tastes a bit sweet and is usually well tolerated. The root of Panax ginseng appeared nontoxic to rats, dogs, and humans [176].

In mice, a lethal oral dose of purified ginseng was determined to be higher than 5 g/kg, the highest dose that can be orally given to a mouse and considered good practice at the maximal dose volumes without violating animal welfare. That level is equivalent to about 0.4 g/kg of oral ginseng given to an adult man [172]. In a 2-year human study, 14 out of a total of 133 subjects were reported to experience side effects attributed to long-term exposure of ginseng when consumed at levels up to 15 g/day [177]. The long-term side effects of ginseng are characterized by hypertension, nervousness, sleeplessness, skin rash, diarrhea, confusion, depression, or depersonalization. The effects were described as “ginseng abuse syndrome”. This level of ginseng consumption far exceeds the recommended daily intake of 1–2 g/day of Asian ginseng, in which 4–5% are ginsenosides [178]. Consuming six of 500-mg ginseng capsules daily was reported to produce side effects such as hypertension, gastrointestinal disturbances, insomnia and nervousness. The validity of these observations is difficult to evaluate quantitatively. Moreover, as is the case in many studies with ginseng, the ginsenoside content of ginseng consumed was not determined [179].

Both American and Asian ginsengs are stimulants and may cause nervousness or sleeplessness, particularly if taken at very high doses. Other reported side effects that occurred in some individuals include high blood pressure, insomnia, restlessness, anxiety, euphoria, diarrhea, vomiting, headache, nosebleed, breast pain and vaginal bleeding. Siberian ginseng may cause nervousness and restlessness in some individuals. In rare cases, Siberian ginseng may cause mild diarrhea. Siberian ginseng is not recommended for individuals with very high blood pressure. It may cause insomnia in some people if taken too close to bedtime. If symptoms like breathing problems, tightness in the throat or chest, chest pain, skin hives, rash, or itchy or swollen skin develop, the use of Siberian ginseng should stop.

In conclusion, the most common side effects of ginseng resulted from its overdose are nervousness and excitability. These side effects usually decrease after the first few days. In inappropriate uses, the most common side-effects are the inability to sleep and high blood pressure. Other side-effects include nausea, diarrhea, euphoria, headaches, epistaxis, mastalgia, eruptions, and vaginal bleeding [180]. Ginseng may lower levels of blood sugar; this effect may be seen more in people with diabetes. Therefore, diabetic patients who are taking anti-diabetic medicine should be cautious with Asian ginseng and monitor their blood sugar levels closely. Because ginseng has an estrogen-like effect, women who are pregnant or breastfeeding should take it at recommended doses. Occasionally, there have been reports of more serious side effects, such as asthma attacks, increased blood pressure, palpitations, and, in postmenopausal women, uterine bleeding.

Active substances inside herbs can trigger side effects and interact with other herbs’ active substances, supplements or medications. Interactions between ginseng and phenelzine (a monoamine oxidase inhibitor) and warfarin have been reported [181]. For these reasons, herbs should be taken with care, under supervision of a practitioner knowledgeable in the field of botanical medicine.

CONCLUSIONS

The present review collects about 107 active or inactive chemical entities obtained from the roots, leaves, and flower buds of various ginseng species. In general, these entities can be categorized into the following: saponins, polysaccharides, polyynes, flavonoids, and volatile oils. Only saponins show bioactivities. The current biological findings of ginseng (and its ginsenosides) and its clinical applications include anti-hyperglycemic effect of ginseng that has been showing positive results, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic effects. The immune-stimulatory activity of ginseng and its ginsenosides has suggested their uses as an adjuvant or immunotherapeutic agent to enhance immune activity, appetite and life quality of cancer patients during their chemotherapy and radiation. Daily consumption of Asian or American ginseng ranges from 1–25 g depending on personal needs and tolerance, quality of ginseng roots, and cookery. Recent studies enriched our understanding of aphrodisiac effect, cardiovascular effect, neuropharmacological effect of ginseng, and especially its individual active ginsenosides from the modern pharmacological perspectives. Although controversy of clinical outcome of ginseng trials remains, many factors can contribute to the controversy, especially the quality of ginseng and its related active ingredients.

Table 2.

Structures and Bioactivity of Metabolites of Protopanaxadiol Saponins

| No. | Name | R1 | R2 | Main activity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Compound K (IH-901) | -Glc | -Glc-Ara(p) | Antigenotoxic; Antitumor | [22–24] |

| 2 | IH-902 | H | -Glc-Ara(p) | Antigenotoxic | [22] |

| 3 | IH-903 | H | -Glc-Ara(f) | Antigenotoxic | [22] |

| 4 | PPD | H | H | Increase apoptosis | [10] |

| 5 | * | =O | Glc | Not defined | [25] |

*= 12β-hydroxydammar-3-one-20 (S)-O-β-D-glucopyranoside.

Table 3.

Structures and Activity of Protopanaxatriol Saponins

| No. | Name | R1 | R3 | Main Activity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Re | O-Glc3-Rha | Glc | Proliferation inhibition | [26] |

| 2 | 20-gluco-G-Rf | O-Glc2-Glc | Glc | Not defined | |

| 3 | Rf | O-Glc2-Glc | H | Not defined | |

| 4 | Rg1 | O-Glc | Glc | Neuroprotective effect; Induce apoptosis; Estrogen-like effect | [27, 28] |

| 5 | Rg2 | O-Glc2-Rha | H:20(S) | ||

| 6 | Rh1 | H | H | Increase immune activity; Phytoestrogen; Inhibition on proliferation | [10, 29] |

| 7 | Rg2(R) | O-Glc2-Rha | H:20(R) | ||

| 8 | NS-R1 | O-Glc2-Xyl | Glc | Not defined | |

| 9 | NS-R2 | Glc2-Xyl | H | Not defined | [30] |

| 10 | NS-R3 | Glc | Glc6-Glc | Not defined | [31] |

| 11 | * | Glc2-Rha (p) | Glc6-Xyl | Not defined | [47] |

| 12 | QS-L4 | Glc | Glc6-Xyl | Not defined | [19] |

*= Floralquinquenoside E.

Table 4.

Structures and Activity of Ocotillol Saponins

Table 5.

Structures and Activity of Saponins with Double Bonds

| No. | Name | R1 | R2 | Main activity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rg5 | Glc-glc | H | Improved memory dysfunction; anxiolytic | [34, 35] |

| 2 | Rh3 | Glc | H | Induce differentiation | [36] |

| 3 | F4 | H | Rha-glc-o | Not defined | |

| 4 | Rh4 | H | Glc-o | Not defined | |

| 5 | * | Glc2-xyl | H | Not defined | [37] |

*= 3β, 12β-dihydroxydammar-(E)-20(22), 24-di-ene-6-O-β-D-xylopyranosy-(1–2)-β-D-glucopyranoside.

Table 6.

Structures and Activity of 25-OH Protopanaxadiol Saponins

| No. | Name | R | Main activity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | * | Glc2-Glc | Not defined | [38] |

| 2 | Ft2 | Glc2-Glc2-Xyl | Not defined | [39] |

| 3 | 25-OH-PPD | H | Not defined | [40] |

*= 12β, 20 (R), 25-trihydroxydammar-3-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1–2)-β- D-glucopyranoside.

Table 7.

Structures and Activity of 25-OH 20(22)-en Saponins

| No. | Name | R1 | R2 | Main activity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | Glc2-Glc | H | Not defined | [38] |

| 2 | B | H | OGlc2-Xyl | Not defined | [37] |

| 3 | C | H | Oglc2-Ara (p) | Not defined | [37] |

A= 12β, 25-dihydroxydammar-(E)-20 (22)-ene-3-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1–2)- β-D- glucopyranoside.

B= 3β,12β,25-trihydroxydammar-(E)-20(22)-ene-6-O-β-D-xylopyranosyl-(1–2)- β-D-glucopyranoside.

C=3β,12β,25-trihydroxydammar-(E)-20(22)-ene-6-O-α-L-rhamnopyranosy-(1–2)- β-D-glucopyranoside.

Table 8.

Structures and Activity of 25-OH Protopanaxatriol Saponins

*= 3β,12β, 20, 25-tetrahydroxydammaran-6-O-β-D-xylopyranosyl -(1–2)-β-D-glucopyranoside.

Table 9.

Structures and Activity of 24-OH 25-en Saponins

Table 10.

Structures and Activity of 23-OH 24, 25-epoxy 20(22)-en Protopanaxatriol Saponins

| No. | Name | R | Activity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rg8 | Glc2-Ara (P) | Not defined | [46] |

Table 11.

Structures and Activity of 25-Hydroperoxy 23-en Saponins

Table 12.

Structures and Activity of 24-Hydroperoxy 25-en Saponins

Table 13.

Structures and Activity of 25-OH, 23(24)en Saponins

Table 14.

Structures and Activity of 23(24), 25(26)-en Protopanaxadiol Saponins

Table 15.

Structures and Activity of 26-OH Protopanaxadiol Type Saponins

Table 16.

Structures and Activity of 24, 25-OH Protopanaxatriol Saponins

Table 17.

Structures and Activity of 7-OH, 5(6)-en Saponins

Table 19.

The Fundamental Theory of Five Elements Used in TCM Reflects the Yin-Yang Balance

| 5 Elements | Wood | Fire | Earth | Metal | Water |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavors | sour | bitter | sweet | pungent | salty |

| Zang (organ) | liver | heart | spleen | lung | kidney |

| Fu (organ) | gall bladder | small intestine | stomach | large intestine | urinary |

| Senses | eye | tongue | mouth | nose | ear |

| Tissue | tendon | vessel | muscle | hair/skin | bone |

| Directions | east | south | center | west | north |

| Changes | germinate | grow | transform | reap | store |

| Color | green | red | yellow | white | black |

ABBREVIATIONS

- TCM

Traditional Chinese medicine

- NO

Nitric oxide

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- SAR

Structure-activity-relationship

References

- 1.Jiang JW, Xiao QS. Handbook of active constituents of medicinal plants. People’s Health Publisher; Beijing: 1985. pp. 503–516. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park EK, Shin YW, Lee HU. Inhibitory effect of ginsenoside Rb1 and compound K on NO and prostaglandin E2 biosynthesis of RAW264.7 cells induced by lipopolysaccharide. Bio Pharm Bull. 2005;28:652–656. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee YJ, Jin YR, Lim WC. Ginsenoside-Rb1 acts as a weak phytoestrogen in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Arch Pharm Res. 2003;26:58–63. doi: 10.1007/BF03179933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujimoto J, Sakaguchi H, Aoki I. Inhibitory effect of ginsenoside-Rb2 on invasiveness of uterine endometrial cancer cells to the basement membrane. Eur J Gynecol Oncol. 2001;22:339–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu ZQ, Luo XY, Sun YX. Can ginsenosides protect human erythrocytes against free-radical-induced hemolysis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1572:58–66. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00281-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu ZQ, Luo XY, Liu GZ. In vitro study of the relationship between the structure of ginsenoside and its antioxidative or prooxidative activity in free radical induced hemolysis of human erythrocytes. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:2555–2558. doi: 10.1021/jf026228i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Surh YJ, Lee JY, Choi KJ, Ko SR. Effects of selected ginsenosides on phorbol ester-induced expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and activation of NF-kappaB and ERK1/2 in mouse skin. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;973:396–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berek L, Szabo D, Petri IB, Shoyama Y, Lin YH, Molnar J. Effects of naturally occurring glucosides, solasodine glucosides, ginsenosides and parishin derivatives on multidrug resistance of lymphoma cells and leukocyte functions. In Vivo. 2001;15:151–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keum YS, Han SS, Chun KS, Park KK, Park JH, Lee SK, Surh YJ. Inhibitory effects of the ginsenoside Rg3 on phorbol ester-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression, NF-kB activation and tumor promotion. Mutat Res. 2003;523:75–85. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(02)00323-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Popovich DG, Kitts DD. Structure-function relationship exists for ginsenosides in reducing cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis in the human leukemia (THP-1) cell line. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;406:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00398-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bae EA, Han MJ, Kim EJ. Transformation of ginseng saponins to ginsenoside Rh2 by acids and human intestinal bacteria and biological activities of their transformants. Arch Pharmacol Res. 2004;27:61–67. doi: 10.1007/BF02980048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim YS, Jin SH. Ginsenoside Rh2 induces apoptosis via activation of caspase-1 and -3 and up-regulation of Bax in human neuoblastoma. Arch Pharm Res. 2004;27:834–839. doi: 10.1007/BF02980175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SE, Lee YH, Park JH. Ginsenoside-Rs4, a new type of ginseng saponin concurrently induces apoptosis and selectively elevates protein levels of p53 and p21WAF1 in human hepatoma SK-HEP-1 cells. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:507–511. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00415-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen JT, Li HZ, Wang D, Zhang YJ, Yang CR. New dammarane monodesmosides from the acidic deglycosylation of notoginseng-leaf saponins. Helvetica Chimica Acta. 2006;89:1442–1448. [Google Scholar]

- 15.He KJ, Liu Y, Yang Y, Li P, Yang L. A dammarane glycoside derived from ginsenoside Rb3. Chem Pharm Bull. 2005;53:177–179. doi: 10.1248/cpb.53.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lei J, Li X, Gong XJ, Zheng YN. Isolation, synthesis and structures of cytotoxic ginsenoside derivatives. Molecules. 2007;12:2140–2150. doi: 10.3390/12092140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Besso H, Kasai R, Wei JX, Wang JF, Saruwatari Y, Fuwa T, Tanaka O. Further studies on dammarane-saponins of American ginseng, roots of Panax quinquefolium L. Chem Pharm Bull. 1982;30:4534–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshikawa M, Murakami T, Yashiro K, Yamahara J, Matsuda H, Saijoh R, Tanaka O. Bioactive saponins and glycosides. XI. Structures of new dammarane-type triterpene oligoglycosides, quinquenosides I, II, III, IV, and V, from American ginseng, the roots of Panax quinquefolium L. Chem Pharm Bull. 1998;46:647–54. doi: 10.1248/cpb.46.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang JH, Li W, Sha Y, Tezuka Y, Kadota S, Li X. Triterpenoid saponins from leaves and stems of Panax quinquefolium L. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2001;3:123–30. doi: 10.1080/10286020108041379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chihiro T, Itsuki H, Tomoharu K, Katsuko K. Metabolite 1 of protopanaxadiol-type saponins, an axonal regenerative factor, stimulates teneurin-2 linked by PI3-Kinase cascade. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;31:1158–1164. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang ZG, Sun HX, Ye Y. Ginsenoside Rd from Panax notoginseng is cytotoxic towards HeLa cancer cells and induces apoptosis. Chem Biodiv. 2006;3:187–197. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200690022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee BH, Lee SJ, Hui JH. In vitro antigenotoxic activity of novel ginseng saponin metabolites formed by intestinal bacteria. Planta Medica. 1998;64:500–503. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shin JE, Park EK. Cytotoxicity of compound K (IH-901) and ginsenoside Rh2, main biotransformants of ginseng saponins by bifidobacteria, against some tumor cells. J Ginseng Res. 2003;27:129–134. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee JY, Shin JW, Chun KS. Antitumor promotional effects of a novel intestinal bacterial metabolite (IH-901) derived from the protopanaxadiol type ginsenosides in mouse skin. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:359–367. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen GT, Yang M, Song Y, Lu ZQ, Zhang JQ, Huang HL, Wu LJ, Guo DA. Microbial transformation of ginsenoside Rb1 by Acremonium strictum. Appl Microbio Biotech. 2008;77:1345–1350. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1258-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ge YC, Liu P, Han CX. Influence of ginsenoside Rb1, Rg1, Re and Rh1 on Hela cells. Pharmacol Clin TCM. 1997;13:18–21. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen WZ, Ou YXN. Study on the mechanism of ginsenoside anticancer. Fujian J TCM. 2005;36:52–53. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan RY, Chen WF, Dong A. Estrogen-like activity of ginsenoside Rg1 derived from Panax notoginseng. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:3691–5. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.8.8717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee Y, Jin Y, Lim W. A ginsenoside-Rh1, a component of ginseng saponin, activates estrogen receptor in human breast carcinoma MCF-7 cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;84:463–8. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teng RW, Li HZ, Chen JT, Wang DZ, He YN, Yang CR. Complete assignment of 1H and 13C NMR data for nine protopanaxatriol glycosides. Magnet Reson Chem. 2002;40:483–488. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsuura H, Kasai R, Tanaka O, Saruwatari Y, Fuwa T, Zhou J. Further studies on dammarane-saponins of Sanchi-Ginseng. Chem Pharm Bull. 1983;31:2281–7. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Z, Wu CF, Pei G, Guo YY, Li X. Antagonistic effect of pseudoginsenoside-F11 on the behavioral actions of morphine in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;66:595–601. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00260-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Z, Xu NJ, Wu CF, Xiong Y, Fan HP, Zhang WB, Sun Y, Pei G. Pseudoginsenoside-F11 attenuates morphine-induced signaling in Chinese hamster ovary-mu cells. Neuro Report. 2001;12:1453–1456. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200105250-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bao HY, Zhang J, Yeo SJ, Myung CS, Kim HM, Kim JM, Park JH, Cho J, Kang JS. Memory enhancing and neuroprotective effects of selected ginsenosides. Arch Pharm Res. 2005;28:335–342. doi: 10.1007/BF02977802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cha HY, Park JH, Hong JT, Yoo HS, Song S, Hwang BY, Eun JS, Oh KW. Rb1, Rg1, and the Rg5 - Anxiolytic-like effects of ginsenosides on the elevated plus-maze model in mice. Biol Pharm Bull. 2005;28:1621–1625. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim YS, Kim DS, Kim SI. Ginsenoside Rh2 and Rh3 induce differentiation of HL60 cells into granulocytes: modulation of protein kinase C isoforms during differentiation by ginsenoside Rh2. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1998;30:327–338. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(97)00141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen GT, Yang M, Lu ZQ, Zhang JQ, Huang HL, Liang Y, Guan SH, Song Y, Wu LJ, Guo DA. Microbial transformation of 20(S)-Protopanaxatriol-type saponins by Absidia coerulea. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:1203–1206. doi: 10.1021/np070053v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen GT, Yang M, Song Y, Lu ZQ, Zhang JQ, Huang HL, Wu LJ, Guo DA. Microbial transformation of ginsenoside Rb1 by Acremonium strictum. Appl Microbiol Biotech. 2008;77:1345–1350. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1258-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen JT, Li HZ, Wang D, Zhang YJ, Yang CR. New dammarane monodesmosides from the acidic deglycosylation of notoginseng-leaf saponins. Helvetica Chimica Acta. 2006;89:1442–1448. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang XR, Zhang D, Xu JH, Gu JK, Zhao YQ. Determination of 25-OH-PPD in rat plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry and its application in rat pharmacokinetic studies. J Chromatogr (B) 2007;858:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2007.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang W, Zhao YQ, Rayburn ER, Hill DL, Wang H, Zhang RW. In vitro anti-cancer activity and structure-activity relationships of natural products isolated from fruits of Panax ginseng. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2007;59:589–601. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0300-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen JT, Li HZ, Wang D, Zhang YJ, Yang CR. New dammarane monodesmosides from the acidic deglycosylation of notoginseng-leaf saponins. Helvetica Chimica Acta. 2006;89:1442–1448. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Komakine N, Okasaka M, Takaishim Y, Kawazo K, Murakam K, Yamada Y. New dammarane-type saponin from roots of Panax notoginseng. J Nat Med. 2006;60:135–137. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang DQ, Fan J, Feng BS, Li SR, Wang XB, Yang CR, Zhou J. Studies on saponins from the leaves of Panax japonicus var. bipinnatifidus seed. Yao Xue Xue Bao. 1989;24:593–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dou DQ, Chen YJ, Liang LH, Pang FG, Shimizu N, Takeda T. Six new dammarane-type triterpene saponins from the leaves of Panax ginseng. Chem Pharm Bull. 2001;49:442–446. doi: 10.1248/cpb.49.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dou DQ, Li W, Guo N, Fu R, Pei YP, Koike KZ, Nikaido TT. Ginsenoside Rg8, a new dammarane-type triterpenoid saponin from roots of Panax quinquefolium. Chem Pharm Bull. 2006;54:751–753. doi: 10.1248/cpb.54.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakamura S, Sugimoto S, Matsuda H, Yoshikawa M. Medicinal flowers. XVII. New dammarane-type triterpene glycosides from flower buds of American ginseng, Panax quinquefolium L. Chem Pharm Bull. 2007;55:1342–1348. doi: 10.1248/cpb.55.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoshikawa M, Sugimoto S, Nakamura S, Matsuda H. Medicinal flowers. XI. Structures of new dammarane-type triterpene diglycosides with hydroperoxide group from flower buds of Panax ginseng. Chem Pharm Bull. 2007;55:571–576. doi: 10.1248/cpb.55.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoshikawa M, Murakami T, Ueno T, Yashiro K, Hirokawa N, Murakami N, Yamahara J, Matsuda H, Saijoh R, Tanaka O. Bioactive saponins and glycosides. VIII. Notoginseng (1): new dammarane-type triterpene oligoglycosides, notoginsenosides-A, - B, - C, and -D, from the dried root of Panax notoginseng (Burk.) F. H. Chen. Chem Pharm Bull. 1997;45:1039–1045. doi: 10.1248/cpb.45.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yoshikawa M, Murakami T, Yashiro K, Yamahara J, Matsuda H, Saijoh R, Tanaka O. Bioactive saponins and glycosides. XI. Structures of new dammarane-type triterpene oligoglycosides, quinquenosides I, II, III, IV, and V, from American ginseng, the roots of Panax quinquefolium L. Chem Pharm Bull. 1998;46:647–654. doi: 10.1248/cpb.46.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Masayuki Y, Toshiyuki M, Takahiro U. Biactive sapooninsand glycosides. VIII notoginseng (1):new dammarane-type tritrepene-oligoglycosides, notoginsenoside-A,-B,-C and -D, from the dried root of Panax notoginseng(Burk) F.H. Chen. Chem Pharm Bull. 1997;45:1039–1045. doi: 10.1248/cpb.45.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Masayuki Y, Toshio M, Kenichi Y, Toshiyuki M, Hisashi M. Bioactive Saponins and Glycosides. XIX. Notoginseng (3): Immunological adjuvant activity of notoginsenosides and related saponins: Structures of Notoginsenosides-L, -M, and -N from the Roots of Panax notoginseng. Chem Pharm Bull. 2001;49:1452–1456. doi: 10.1248/cpb.49.1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Qiu F, Ma ZZ, Xu SX, Yao XS, Che CT, Chen YJ. A pair of 24-hydroperoxyl epimeric dammarane saponins from flower-buds of Panax ginseng. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2001;3:235–240. doi: 10.1080/10286020108041396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang JH, Li W, Li X. A new saponin from the leaves and stems of Panax quinquefolium L. collected in Canada. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 1998;1:93–97. doi: 10.1080/10286029808039849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang JH, Li W, Sha Y, Tezuka Y, Kadota S, Li X. Triterpenoid saponins from leaves and stems of Panax quinquefolium L. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2001;3:123–130. doi: 10.1080/10286020108041379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dou D, Wen Y, Weng M, Pei Y, Chen Y. Minor saponins from leaves of Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 1997;22:35–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hao XH, Li PY, Li X, Liu YQ. Saponins in the fruit of Panax quinquefolius from Canada. Zhongcaoyao. 2000;31:801–803. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Covington MB. Traditional Chinese Medicine in the treatment of diabetes. Diabetes Spectrum. 2001;14:154–159. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Blumenthal M. Herb sales down 15 percent in mainstream market. Herbalgram. 2001;51:69. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tyler VE. The honest herbal-A sensible guide to the use of herbs and related remedies. 3. New York: Haworth Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vuksana V, Sievenpipera JL. Herbal remedies in the management of diabetes: Lessons learned from the study of ginseng. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2005;15:149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ryu JK, Lee T, Kim DJ, Park IS, Yoon SM, Lee HS, Song SU, Suh JK. Free radical-scavenging activity of Korean red ginseng for erectile dysfunction in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus rats. Urology. 2005;65:611–615. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yoon SH, Han EJ, Sung JH, Chung SH. Anti-diabetic effects of compound K versus metformin versus compound K-metformin combination therapy in diabetic db/db mice. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007;30:2196–2200. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Attele AS, Zhou YP, Xie JT, Wu JA, Zhang L, Dey L, Pugh W, Rue PA, Polonsky KS, Yuan CS. Antidiabetic effects of Panax ginseng berry extract and the identification of an effective component. Diabetes. 2002;51:1851–1858. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.6.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Luo JZ, Luo L. American ginseng stimulates insulin production and prevents apoptosis through regulation of uncoupling protein-2 in cultured beta-cells. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2006;3:365–372. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nel026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sievenpiper JL, Arnason JT, Leiter LA, Vuksan V. Decreasing, null and increasing effects of eight popular types of ginseng on acute postprandial glycemic indices in healthy humans: the role of ginsenosides. J Am Coll Nutr. 2004;23:248–258. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2004.10719368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sievenpiper JL, Sung MK, Di Buono M, Seung-Lee K, Nam KY, Arnason JT, Leiter LA, Vuksan V. Korean red ginseng rootlets decrease acute postprandial glycemia: results from sequential preparation- and dose-finding studies. J Am Coll Nutr. 2006;25:100–107. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2006.10719519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vuksan V, Sievenpiper JL, Koo VYY, Francis T, Beljan-Zdravkovic U, Xu Z, Vidgen E. American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius L) reduces postprandial glycemia in nondiabetic subjects and subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1009–1013. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.7.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sotaniemi EA, Haapakoski E, Rautio A. Ginseng therapy in non-insulin-dependent diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:1373–1375. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.10.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Koshland DE., Jr The molecule of the year. Science. 1992;258:1861. doi: 10.1126/science.1470903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jia L. Nitric oxide research and new drugs: Challenges and success. Commentary on the 1998 Nobel Prize in Medicine. Science (Chinese) 1999;51:49–52. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jia L, Furchgott RF. Inhibition by sulfhydryl compounds of vascular relaxation induced by nitric oxide and endothelium-derived relaxing factor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;267:371–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jia L, Furchgott RF. Blockade of nitric oxide-induced relaxation of rabbit aorta by cysteine and homocysteine. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 1997;18:11–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]