Abstract

Eukaryotic transcription by RNA polymerase II is a highly regulated process and mainly divided into three major steps: initiation, elongation, and termination. Each step of transcription is controlled by a number of cellular factors. Positive transcription factor b, P-TEFb, is composed of cyclin-dependent kinase 9 and a regulatory cyclin (T1/T2). P-TEFb promotes transcriptional elongation of RNA polymerase II by using the catalytic function of CDK9 to phosphorylate various substrates during transcription. P-TEFb is inactivated by sequestration in a complex with the Hexim1 protein and 7SK RNA. The structure of this inactive P-TEFb complex and the mechanisms controlling its equilibrium with the active complex are poorly understood. Here, we used a photoactive nucleotide, 4-thioU, to study the interactions between 7SK RNA and Hexim1. We identified a specific cross-link between nucleotide U30 of 7SK RNA and amino acids 210–220 of Hexim1, in the context of both a minimal RNA-binding site and a full reconstituted 7SK/Hexim1/P-TEFb ribonucleoprotein complex. We also show that a minimal 7SK RNA hairpin comprising nucleotides 24–87 can bind specifically to Hexim1 in vivo. Our results directly demonstrate that the Hexim1 binding site is located in the 24–87 region of 7SK RNA and that the protein residues outside the basic domain of Hexim1 are involved in specific RNA interactions.

Keywords: Hexim1, 7SK RNA, P-TEFb, 4-thioU cross-linking

Introduction

Transcription elongation by RNA polymerase II (Pol II) is a tightly controlled process that involves a number of cellular factors. The positive transcription elongation factor b (P-TEFb) is one important factor involved in regulation of transcription (reviewed in (1,2)). P-TEFb is a heterodimer with a catalytic subunit, the cyclin-dependent kinase 9 (CDK9), and a regulatory cyclin T, cyclin T1/T2. P-TEFb promotes processive elongation by phosphorylating the C-terminal domain of Pol II, the DRB (5,6-dichloro-1-β-ribofuranosylbenzimidazole)-sensitive inactivation factor (DSIF) (3,4), and negative elongation factor (NELF). P-TEFb plays a crucial role in controlling HIV-1 Tat-mediated transactivation (5,6), and is recruited to specific cellular promoters by transcription factors such as NF-κB (7) and c-Myc (8). P-TEFb is also recruited to chromatin by the bromodomain protein Brd4 (9,10).

The activity of P-TEFb is controlled by equilibrium between its active form and an inactive form that is bound to the 7SK small nuclear RNA (11–13) and Hexim1 (or Hexim2) protein (14,15). Under normal conditions, about half of P-TEFb is bound to the 7SK/Hexim1 complex. P-TEFb can be activated by release from this complex in response to stress-inducing agents such as UV irradiation, actinomycin D, DRB, and HMBA (11,12,16) and in response to HIV-1 Tat protein (17). However, little is known about the mechanisms that control the equilibrium between active and inactive P-TEFb.

One way to shift this equilibrium is by simple competition between P-TEFb-binding factors. For instance, Hexim1 and Tat compete for binding to P-TEFb, and overexpression of Hexim1 reduces Tat transactivation (14,18–20). Another mechanism controlling this equilibrium is protein phosphorylation. The Hexim1/P-TEFb complex can be disrupted by phosphorylating Hexim1 via the PI3K/Akt pathway (21). Also, phosphorylation of CDK9 on residue T186 is required for complex assembly (22) and PP2B and PP1α can cooperatively cause the release of P-TEFb by dephosphorylating this residue (23). Another insight into the mechanism of P-TEFb activation comes from reports that 7SK RNA also exists in several other snRNP complexes, including hnRNP A1, A2, R and Q (24,25). When 7SK/Hexim1/P-TEFb complexes are disrupted by treatment with actinomycin D or DRB, release of P-TEFb correlates with increase of 7SK in the other RNP complexes (24,25), suggesting that shuttling of 7SK RNA from Hexim1/P-TEFb to other hnRNPs may regulate P-TEFb activation. Recently, the La-related protein LARP7/PIP7S was also shown to be a part of the 7SK snRNP. This protein stabilizes the 7SK snRNP by binding the 3′-end of 7SK and remains bound to the complex even after P-TEFb release (26–28).

Although the active form of P-TEFb has been well studied, little is known about how P-TEFb is inactivated by 7SK and Hexim1. To understand this inactivation, the structure of the P-TEFb/7SK/Hexim1 inactive complex needs to be elucidated as well as the interactions between its components. The functional domains of Hexim1 and its regions involved in RNA or protein interactions have been well characterized. Residues 150–177 comprises a bipartite nuclear-localization signal with an arginine-rich RNA-binding motif, very similar to the RNA-binding site of Tat, where residues 154–156 are critical for RNA binding (29,30). The C-terminal portion of Hexim1 is involved in protein-protein interactions (20,29,31). The Hexim1-CycT1 interaction is mediated by a PYNT motif (residues 202–205) and a coiled-coil region (279–315), while Hexim1 dimerization involves a second coiled-coil region (319–352) (29,31). An acidic region of Hexim1 (211–249) interacts with the basic 7SK RNA-binding region, resulting in a Hexim1 conformation that masks the PYNT motif, thus preventing Hexim1 binding to CycT1 (32). However, when 7SK RNA binds to the basic region of Hexim1, the acidic region is released and the PYNT motif is unmasked and accessible for CycT1 interaction. These studies identify the Hexim1 regions that interact with 7SK, but the molecular details of their interactions are not known.

To understand how the P-TEFb/Hexim1/7SK complex inhibits P-TEFb activity, we probed the interaction between Hexim1 and 7SK RNA by photo-cross-linking with a modified nucleotide 4-thiouridine (4-thioU). Using a 7SK minimal hairpin, we found that nucleotide U30 of 7SK cross-links to region 210–220 of Hexim1, which constitutes amino acids outside of the basic domain. We used functional assays to show the importance of this interaction for optimal RNA binding and P-TEFb inhibition. We then recapitulated this cross-link in the context of a full P-TEFb/Hexim1/7SK complex to determine the functional significance of U30 in RNA-protein interactions. Our results demonstrate that Hexim1 directly interacts with the 24–87 region of 7SK RNA. In addition, we show that Hexim1 specially interacts with the 7SK(24–87) RNA in vivo. This study also demonstrates that 4-thioU-mediated cross-linking can be a powerful tool for studying the structure of 7SK RNP complexes.

Results

Since Hexim1 binds 7SK RNA in the absence of P-TEFb (29), we first studied this interaction in the absence of P-TEFb. Hexim1 has been suggested to bind to the distal portion of the 5-end helix of 7SK RNA (Figure 1A), between positions 24 and 87 (33). Therefore, this region of 7SK was chosen to design a minimal RNA hairpin, 7SK(24–87), with two additional G-C closing pairs (Figure 1B). Before performing cross-linking experiments, we examined the binding of this minimal hairpin to Hexim1 by electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA). 5′-end labeled 7SK(24–87) was incubated with increasing concentrations of purified 6xHis-tagged wild-type Hexim1 and RNA-protein complexes were resolved by native PAGE (Figure 2A). We observed two retarded bands, with the slower band predominant at the higher Hexim1 concentration. This result suggests that more than one Hexim1 molecule binds to the 7SK RNA hairpin. As a control, we used an N-terminal deletion mutant of Hexim1 (181–359), which does not contain the 7SK RNA-binding site (29). As expected, this mutant Hexim1 did not bind the 7SK(24–87) hairpin (Figure 2A). Finally, we observe that Hexim1 does not bind to an RNA hairpin corresponding to the 3′ stem-loop of 7SK (Figure 2A, right panel). These controls show that binding of Hexim1 to the 7SK(24–87) hairpin is specific under these in vitro conditions.

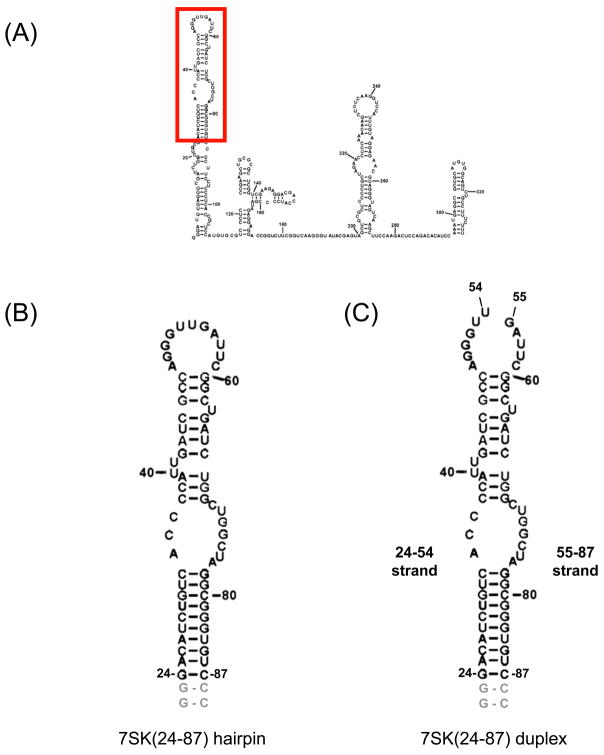

Figure 1. 7SK RNA constructs used in this study.

(A) Secondary structure of 7SK RNA (adapted from (33)). The minimal binding site for Hexim1 protein is boxed in red (enlarged in B). (B) Secondary structure of 7SK(24–87) RNA hairpin. This RNA hairpin consists of nucleotides 24–87, with two additional G-C base pairs (light gray). (C) Secondary structure of 7SK(24–87) RNA duplex. This RNA duplex is identical to the 7SK(24–87) hairpin, but the capping loop contains a break between positions 54 and 55. Nucleotides are numbered according to their positions in full-length 7SK RNA.

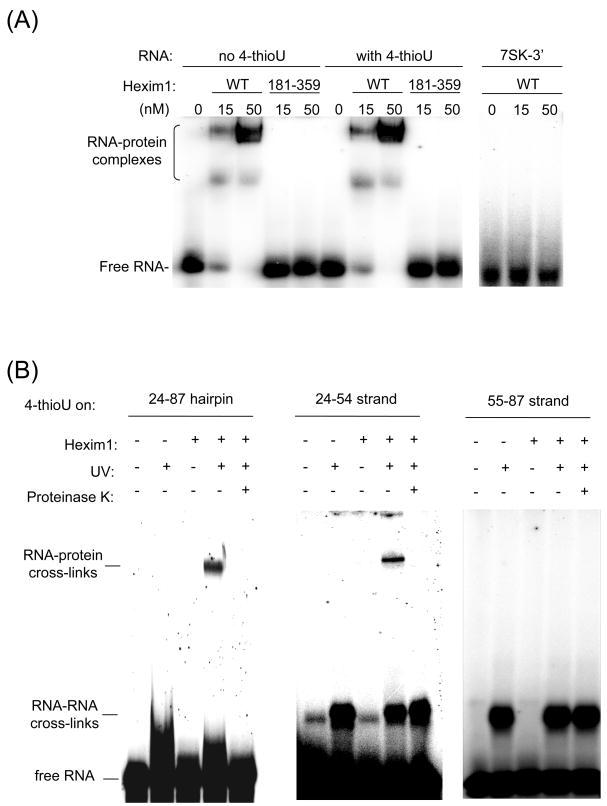

Figure 2. Hexim1 cross-links to the 7SK(24–87) hairpin on its 25–54 strand.

(A) Hexim1 binds to 7SK(24–87) hairpin in vitro. Hexim1 binding to the 7SK(24–87) hairpin was analyzed by EMSA using 5′-end labeled 7SK(24–87) hairpin (with or without 4-thioU) and indicated amounts of purified wild-type (WT) Hexim1. Hexim1 (181–359) is a N-terminal deletion mutant without the RNA-binding site (29). The right panel is a control with an RNA hairpin corresponding to the 3′ stem-loop of 7SK. (B) Hexim1 cross-links to the 25–54 strand of 7SK(24–87). 5′-end labeled 7SK(24–87) hairpin or 7SK(24–87) RNA duplexes containing randomly incorporated 4-thioU on either strand were bound to purified Hexim1 protein and UV-irradiated (see text for details). Control samples were treated with proteinase K. Cross-linked products were resolved by 5% denaturing PAGE.

Hexim1 cross-links to a 7SK minimal hairpin

To probe the interactions between Hexim1 and the 7SK hairpin, the modified nucleotide 4-thioUTP was randomly incorporated during in vitro transcription of 7SK(24–87). This cross-linking probe has been widely used to study RNA-RNA and RNA-protein interactions (reviewed in (34)). Indeed, we have previously used 4-thioU cross-linking to investigate RNA-protein interactions in P-TEFb-Tat-TAR ribonucleoprotein complex (35–38). Upon long wave UV irradiation, the thio group will react with neighboring nucleotides and amino acids to form covalent cross-links. Incorporation of 4-thioU into 7SK(24–87) did not affect binding to Hexim1 protein (Figure 2A). For cross-linking, 5′-end labeled 7SK(24–87) hairpins containing 4-thioU were incubated in the presence and absence of Hexim1, irradiated with UV light, and analyzed by denaturing PAGE (Figure 2B, left panel). UV irradiation of the RNA-protein complex gave rise to a slower moving band, corresponding to a cross-linked product. When samples were treated with proteinase K, this band disappeared, indicating that it is an RNA-protein cross-link product.

Hexim1 cross-links to the 24–54 region of 7SK

To facilitate identification of the cross-link site, we repeated the cross-link experiments using a duplex RNA instead of a hairpin. Since the loop structure of the 7SK(24–87) hairpin is not required for Hexim1 binding (33), we analyzed Hexim1 binding to a 7SK duplex with a break in the capping loop between positions 54 and 55. The duplex was formed by annealing a strand corresponding to positions 24–54 to a strand corresponding to positions 55–87 (Figure 1C). In cross-linking experiments, either the 24–54 strand or the 55–87 strand contained 4-thioU. In each case, only the 4-thioU-containing strand was 5′-end labeled. For the duplex containing 4-thioU on the 24–54 strand, Hexim1 binding and UV irradiation gave rise to two bands of slower mobility than the free RNA (Figure 2B, middle panel). The lower, more intense band was present even without Hexim1 in the reaction, suggesting that it corresponds to an RNA-RNA cross-link. The lighter band, with the slowest mobility, was visible only in the presence of Hexim1, suggesting that it is an RNA-protein cross-link. Treatment with proteinase K after UV irradiation resulted in the disappearance of the upper band, confirming that it is an RNA-protein cross-link. The lower band was not affected by proteinase K treatment, confirming that it is an RNA-RNA cross-link.

The efficiency of the RNA-protein cross-link was relatively low (about 2–3%). This low efficiency can be explained in part by the random incorporation of 4-thioU during transcription. With approximately one label per transcript, only a small fraction of RNA molecules contains a 4-thioU at the correct position. The low efficiency may also be due to the suboptimal orientation of the nucleotide involved in cross-linking. Moreover, RNA and proteins are sometimes cross-linked by UV irradiation with low efficiency (39). The RNA-RNA cross-links were formed at higher efficiencies (5–7%), probably because many uridines are involved in base pairing and are therefore positioned for efficient RNA-RNA cross-linking. RNA-RNA cross-links were only visible with the duplex 7SK RNA (Figure 2B, middle and right panels), not with the hairpin RNA (Figure 2B, left panel). While RNA-RNA cross-links in the duplex were probably between the two strands, RNA-RNA cross-links within the hairpin structure were intramolecular. The resulting cross-link product may have a migration on gel that is not significantly different from the non-cross-linked linear RNA.

When 4-thioU was incorporated on the 55–87 strand, we again observed RNA-RNA cross-links, but no RNA-protein cross-links (Figure 2B, right panel). When a 7SK RNA duplex containing no 4-thioU was used as a control, no cross-link product was observed, showing that all cross-links were specific for 4-thioU (data not shown). These results demonstrate that Hexim1 cross-links specifically to the 25–54 strand of the hairpin.

Hexim1 cross-links to position U30 of 7SK

We used partial alkaline hydrolysis to map the exact nucleotide cross-linked to Hexim1 (38). Hexim1 was cross-linked with 5′-end labeled 7SK(24–87) duplex containing 4-thioU on the 24–54 strand, and the cross-linked product was purified by PAGE and partially hydrolyzed under alkaline conditions. This treatment hydrolyzes RNA at random positions, resulting in a ladder of hydrolysis products that differ in size by 1 nucleotide and can be analyzed by denaturing PAGE. In the case of the purified cross-link product, when hydrolysis occurs on the 3′ side of the cross-link site, the radiolabeled fragment is still linked to Hexim1 and is therefore too large to enter the 20% polyacrylamide gel. The net result is that the hydrolysis ladder visible on the gel stops at the position immediately 5′ from the cross-link site (note that the 55–87 strand of the 7SK(24–87) RNA duplex is not labeled, and is not visible on the gel).

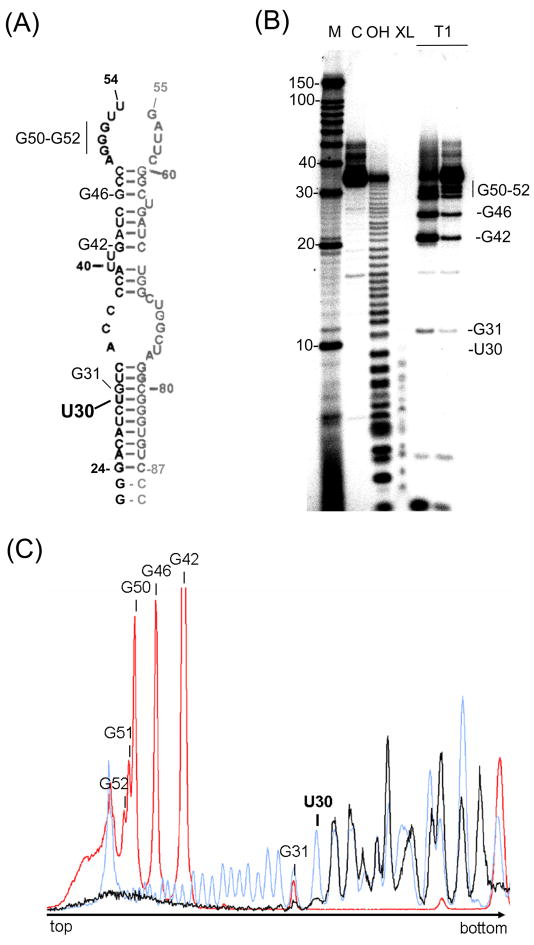

Partial alkaline hydrolysis of the control 24–54 strand and of the purified cross-link product is presented in Figure 3. To mark nucleotide positions in the RNA samples, we used partial digestion with RNase T1, which cleaves 3′ of guanine residues. This cleavage produces fragments of specific size that can be used to identify positions on the alkaline hydrolysis ladder. As shown in Figure 3B, the ladder of the 24–54 strand cross-linked to Hexim1 stops at position 29, (2 nucleotides below G31), suggesting that the cross-linked residue is U30. Figure 3C shows hydrolysis profiles for the cross-link product, control RNA, and RNase T1 digestion generated from the gel in Figure 3B. The profile of cross-linked RNA matches the profile of control RNA up to position C29, indicating that the cross-link site is U30.

Figure 3. Hexim1 cross-links to position U30 of 7SK(24–87).

(A) Secondary structure of 7SK(24–87) duplex. The 5′-end labeled, 24–54 strand is shown in black, and the unlabeled 54–87 strand is shown in gray. Sites of RNase T1 cleavage seen in panel (B) are indicated at G50–G52, G46, G42, and G31. Position U30 is also indicated. (B) Hexim1 cross-links at U30. 5′-end labeled (24–54) control RNA and Hexim1-RNA cross-links were partially hydrolyzed under alkaline conditions and analyzed by denaturing PAGE (see Materials and Methods for details). M: Decade RNA marker; C: Untreated 5′-end labeled (24–54) RNA strand; OH: partial alkaline hydrolysis ladder of 5′-end labeled (24–54) RNA strand; XL: partial alkaline hydrolysis of gel-purified RNA-protein cross-link product; T1: RNase T1 partial hydrolysis of 5′-end labeled (24–54) RNA strand (at two enzyme concentrations). Sites of RNase T1 cleavage (G residues) are indicated. The hydrolysis ladder of the cross-linked RNA stops immediately before U30, showing that this position is cross-linked to Hexim1 protein. (C) Profiles of partial alkaline hydrolysis. Profiles of the lanes from the gel in panel (B) were generated with ImageGauge (Fujifilm). The control hydrolysis ladder is shown in light blue and the cross-linked RNA is shown in black. Profile of RNaseT1 cleavage is shown in red, and G residues are indicated.

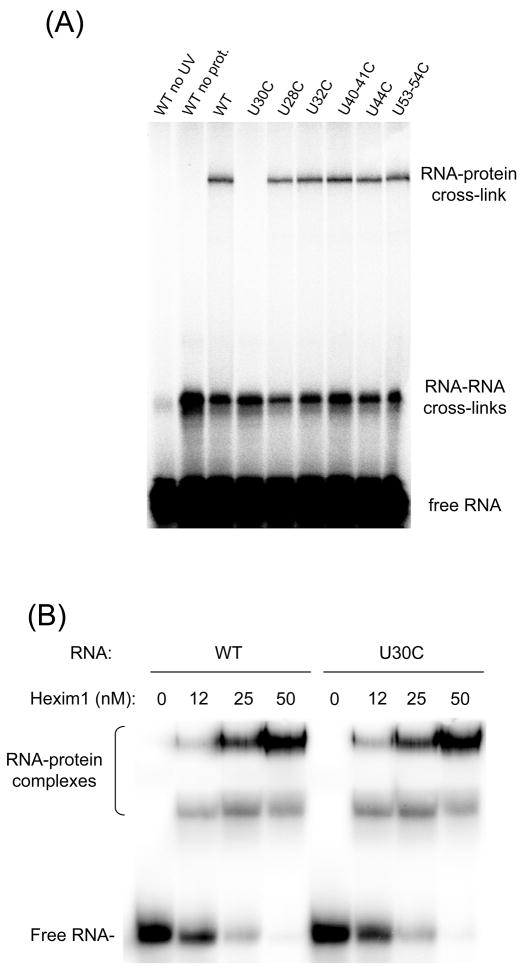

Mutation of U30 abolishes cross-linking to Hexim1

To confirm that Hexim1 cross-links to 7SK at U30, we repeated the cross-linking experiments using mutant RNA duplexes (Figure 4A). Mutating the nucleotide responsible for the cross-link prevents 4-thioU incorporation at this position and the cross-link will be lost. Indeed, when a 7SK(24–87) duplex containing a U30C mutation was used, Hexim1 did not cross-link to the RNA. However, mutating other Us did not affect the RNA-protein cross-link. No single mutation abolished the RNA-RNA cross-links, suggesting that different positions are involved in different RNA-RNA cross-links. A possible explanation for loss of the Hexim1 cross-link with the U30C mutant is that the mutation simply interferes with Hexim1 binding. To eliminate this possibility, we used EMSA to compare the binding of Hexim1 to WT and U30C 7SK(24–87) duplexes. Our results show that the U30C mutation did not affect Hexim1 binding (Figure 4B), confirming that U30 is indeed the site of RNA-protein cross-link.

Figure 4. Mutation at U30 abolishes cross-link of Hexim1 to 7SK(24–87).

(A) Mutating U30 specifically abolishes cross-link of Hexim1 to 7SK(24–87) duplex RNA. Various mutations of U nucleotides on the 24–54 strand were tested for their effect on cross-linking between Hexim1 and 4-thioU-labeled 7SK(24–87) duplexes. Cross-links were produced and analyzed as in Figure 2. (B) Mutation U30C does not affect Hexim1 binding. Hexim1 binding to wild-type (WT) and U30C mutant 5′-end labeled 7SK(24–87) duplex RNA was compared by EMSA.

7SK(24–87) cross-links to region 196–220 of Hexim1

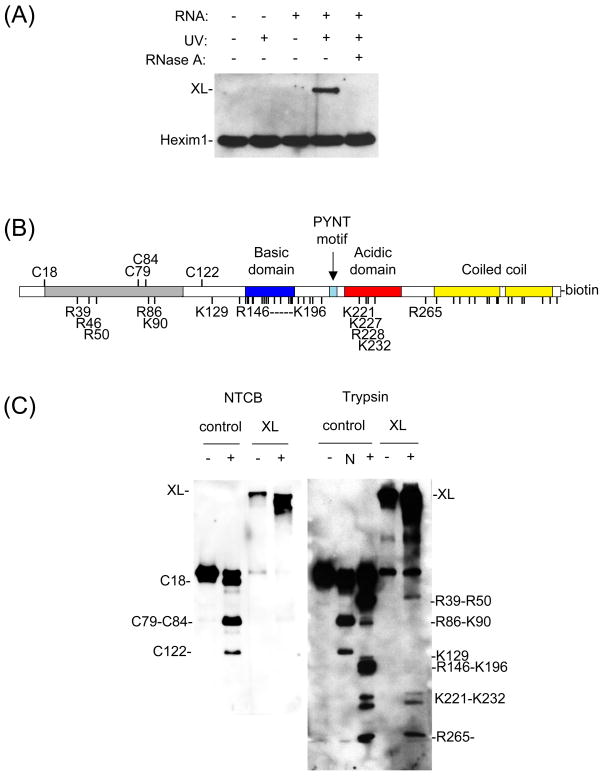

To determine the region of Hexim1 cross-linked to 7SK RNA, we mapped Hexim1-RNA cross-link products by partial cleavage with 2-nitrophenyl 5-cyanatobenzoic acid (NTCB) and with trypsin. For these experiments, we used Hexim1 protein with a biotin label attached to its C-terminus by intein-mediated protein ligation (see Materials and Methods). This biotin label allowed detection of Hexim1 C-terminal cleavage fragments by western blot. Cross-linked products were prepared as described above, except that the RNA was non-radioactive. Western blot analysis using streptavidin-horse radish peroxidase (HRP) shows cross-linked Hexim1-biotin as a band of slower mobility appearing after UV irradiation of the RNA-protein complex (Figure 5A). When the cross-linked reaction product was treated with RNase A, the slower mobility band disappeared, confirming that this band is an RNA-protein cross-linked product.

Figure 5. 7SK(24–87) duplex RNA cross-links to Hexim1 between residues 196–220.

(A) Detection of cross-linked Hexim1-biotin by western blot. 4-thioU-labeled 7SK(24–87) was cross-linked to Hexim1 labeled with biotin on its C-terminus. Cross-links were done as in Figure 2B, but products were separated by 6% SDS-PAGE and analyzed by western blot using streptavidin-HRP. Controls were done with or without RNA, UV irradiation, and RNase treatment. (B) Schematic of Hexim1 sequence. The various domains are shown in color and expected NTCB- and trypsin-cleavage sites are indicated by residue numbers. (C) 7SK(24–87) cross-links to Hexim1 to residues 196–220. Hexim1-biotin was cross-linked to 7SK(24–87), and the reaction product was mapped by NTCB and trypsin cleavage. Positions of cleavage are indicated by numbers. Control indicates samples of non-cross-linked Hexim1-biotin. XL indicates the cross-link product. N indicates an NTCB cleavage ladder of Hexim1-biotin used as a marker.

For mapping, cross-link products were purified by PAGE and partially digested with NTCB or trypsin. Cleaved products were resolved by SDS-PAGE and blotted with streptavidin-HRP, resulting in a ladder of C-terminal cleavage products. When a cross-link site is on the C-terminal side of a cleavage site, the resulting fragment is retarded on the gel. By comparing the patterns of cleavage for a cross-linked product and its non-cross-linked protein, one can deduce the site of cross-link.

We first mapped the cross-linked products with NTCB, which cleaves proteins on the C-terminal side of cysteine residues. NTCB cleavage of Hexim1 resulted in 3 distinct bands: one corresponding to a cleavage at C18, one for C79+C84, and one for C122 (Figure 5B, 5C [left gel]). Hexim1 also contains a cysteine at position 297, but no cleavage was observed for this position. When the cross-linked product was treated with NTCB, all cleavage products were retarded on the polyacrylamide gel, indicating that the cross-link site is located on the C-terminal side of C122, between residues 123–359.

To narrow the cross-linked region, RNA-Hexim1 cross-link products were treated with trypsin, which cleaves on the C-terminal side of arginine and lysine residues not followed by a proline. Expected cleavage sites are indicated in Figure 5B, and observed cleavage is shown in Figure 5C (right gel). An NTCB cleavage ladder was used as a position marker to help identify trypsin cleavage sites. Most trypsin-cleavage sites are grouped in clusters: residues R39–R50, R86-K90, K129, R146-K196, and K221–K232. Smaller fragments starting from R265 are too small to be resolved by SDS-PAGE and appear as a single band at the bottom of the gel. When the cross-linked product was treated with trypsin, fragments corresponding to cleavage at K221 and below migrated the same distance as the noncross-linked protein, but all fragments corresponding to K196 and above all retarded. These results indicate that the cross-link site is between positions 196 and 220. The purified cross-linked products contained small amounts of non-cross-linked product, which could be due to breakdown of some cross-linked products during purification. However, this free Hexim1 was faint compared to the cross-link product and did not impair analysis of cleavage patterns.

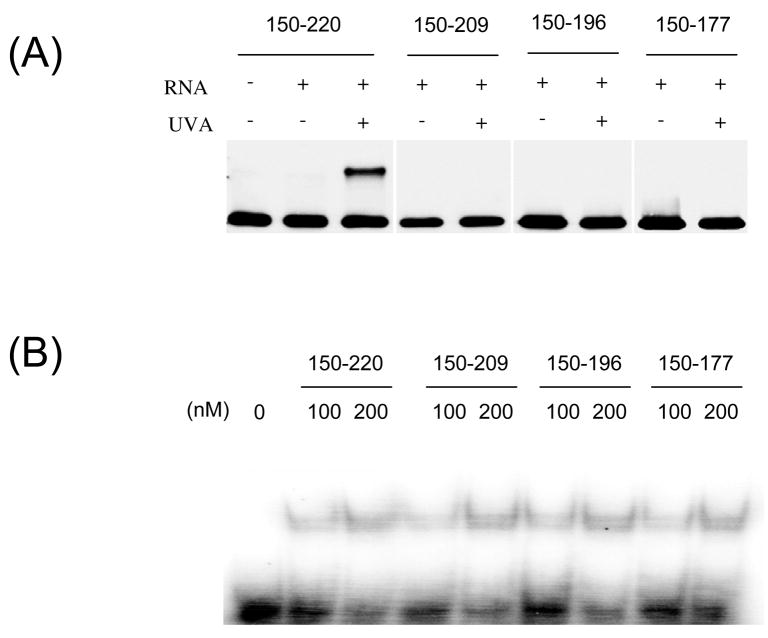

To confirm that the cross-link site is located between positions 196–220, we repeated the cross-linking experiments using a serie of GST fusions containing minimal Hexim1 RNA-binding domains. It was previously shown that the isolated 150–177 domain of Hexim1 is capable of 7SK binding (30). We designed GST fusions of Hexim1 fragments ranging from 150–177 to 150–220 (Figure 6A). These fusions were used in cross-linking experiments with 4-thioU-7SK(24–87) and analyzed by blotting with anti-GST. (The difference in size of these proteins is not visible on the low percentage (6%) of acrylamide that was used to favor transfer of the cross-linked product). The GST-Hex(150–220) protein was able to form a cross-link with 7SK(24–87), but other fusions with region 150–177, −196 or −209 produced no cross-link, showing that region 210–220 is required for formation of this cross-link. Gel shifts experiments showed that all the GST-fusions bound the RNA hairpin with similar affinities (Figure 6B), although the binding was weaker than with full-length Hexim1. Only one retarded band was observed, because these proteins do not have the domains necessary for dimerization.

Figure 6. Residues 210–220 of Hexim1 are required for cross-linking to 7SK(24–87).

(A) Mapping of cross-link site using minimal Hexim1 RNA-binding regions. GST was fused to small fragments of Hexim1 comprising the basic domain (150–177) or extended regions up to 150–220. These constructs were used in cross-linking experiments with 4-thioU-labeled 7SK(24–87). Products were separated by 6% SDS-PAGE and analyzed by western blot using anti-GST. (B) GST-Hexim1 constructs bind RNA with similar affinity. Binding of each GST-Hexim1 fusion to radio-labeled 7SK(24–87) was examined by EMSA. (C) Deletion of residues 210–220 of Hexim1 abolishes cross-link to 7SK(24–87). Wild-type and mutant Hexim1 containing a C-terminal biotin label were cross-linked to 4-thioU labeled 7SK(24–87) and detected by western blot as in Figure 5. (D) Deletion of residues 210–220 reduces affinity of Hexim1 for 7SK(24–87). Wild-type and mutant Hexim1 binding to radiolabeled 7SK(24–87) was examined by EMSA as on Figure 2. Graph shows the percentage of RNA bound at different Hexim1 concentration. Values are means +/− standard error of three independent experiments. (E) Deletion of residues 210–220 of Hexim1 affects its ability to inhibit P-TEFb kinase activity. Purified P-TEFb was incubated with in vitro transcribed 7SK RNA and either wild-type or mutant Hexim1. Kinase activity of P-TEFb was measured by phosphorylation of GST-CTD with radiolabeled ATP. Graph shows relative intensity of phosphorylated GST-CTD band. Values are means +/− standard error of three independent experiments.

To confirm these findings, we repeated the cross-linking experiments with deletion mutants in full-length Hexim1 (Figure 6C). Deletion of residues 196–220 or of 210–220 both abolished the formation of the cross-link. These two mutants bound the hairpin with slightly less affinity then wild-type (Figure 6D), but this difference is not enough to account for the complete loss of the cross-link. Indeed, GST-Hex(150–221) from Figure 6A had even lower affinity but still produced a cross-link. Taken together these results demonstrate that the cross-link site is located between positions 210 and 220 of Hexim1 and that this region also has a modest effect on RNA binding.

To further test the functional relevance of this interaction, we measured the ability of Hexim1 deletion mutants to inhibit P-TEFb kinase activity. Purified P-TEFb was incubated with either wild-type or mutant Hexim1, with or without in vitro transcribed 7SK RNA. The kinase activity of P-TEFb was measured by phosphorylation of GST-CTD with radiolabeled ATP. Radiolabeled GST-CTD was analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Figure 6E). Free P-TEFb gave a strong phosphorylation signal, and incubation with either Hexim1 or 7SK RNA alone did not affect its activity. However, when both Hexim1 and 7SK were present, the kinase activity of P-TEFb was almost completely abolished. The Δ210–220 mutant showed a significantly reduced ability to inhibit P-TEFb, suggesting that the interaction of this region with 7SK is important for maximal P-TEFb inhibition. The Δ196–220 mutant was completely unable to inhbibit P-TEFb, but this was to be expected because this deletion eliminates the PYNT motif required for interaction with P-TEFb. Altogether, these results confirm the cross-link of U30 of 7SK with region 210–220 of Hexim1 and demonstrate the functional importance of this interaction for optimal RNA binding and P-TEFb inhibition.

Hexim1 cross-links to U30 of 7SK RNA in reconstituted P-TEFb complexes

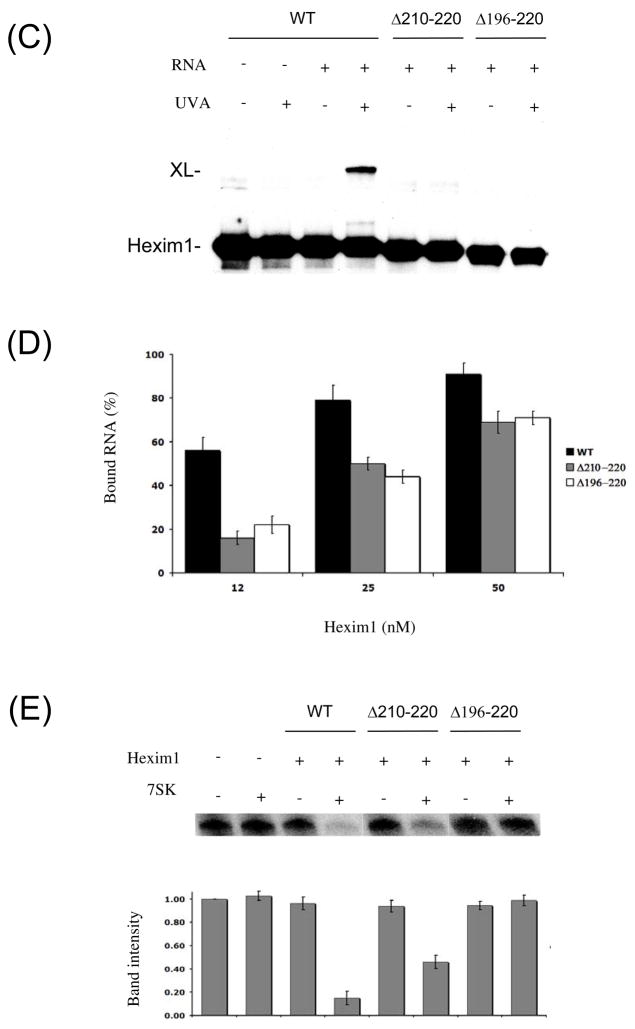

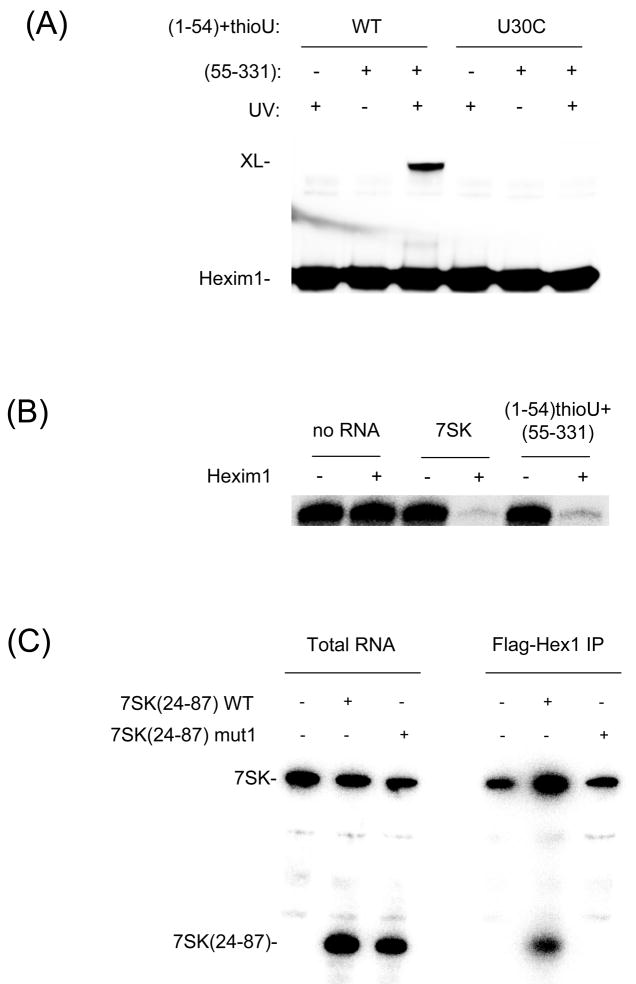

To demonstrate the functional significance of results obtained with the minimal hairpin, we reproduced the Hexim1 cross-link to 7SK RNA in the context of the full 7SK/Hexim1/P-TEFb complex. To that end, we reconstituted a complete 7SK RNA in trans by annealing a 4-thioU-labeled strand corresponding to positions 1–54 to an unlabeled 55–331 strand. Such reconstitution in trans has been previously used in ribosome studies (40). The reconstituted 7SK RNA was bound to purified Hexim1-biotin and P-TEFb and cross-linked as described above. The Hexim1-7SK cross-link product was detected by western blot as on Figure 5A. The cross-link was visible after UV irradiation (Figure 7A), but no cross-link was visible in the absence of UV irradiation. Most importantly, no cross-linked product was seen when the 4-thioU-labeled 1–54 strand was used without the 55–331 strand. This result shows that the 1–54 fragment of 7SK RNA did not cross-link nonspecifically to Hexim1. Finally, when a U30C mutant RNA strand was used, no cross-linking was observed (Figure 7A, right). This result confirms that the cross-link obtained with the full complex is the same as that obtained with the minimal 7SK(24–87) RNA hairpin. From these observations, we conclude that Hexim1 specifically cross-links to U30 of 7SK in the full complex with P-TEFb, just as it does with a minimal hairpin.

Figure 7. Functional significance of Hexim1 interaction with 7SK(24–87).

(A) Hexim1 specifically cross-links to U30 in the full 7SK/Hexim1/P-TEFb complex. Hexim1/7SK/P-TEFb complexes were formed by annealing 4-thioU-labeled 7SK(1–54) strand to unlabeled 7SK(55–331) and binding to purified Hexim1-biotin and P-TEFb. Cross-links with both wild-type (WT) and U30C mutant RNA were analyzed by western blot as in Figure 5A. (B) Reconstituted Hexim1/7SK RNA complexes inhibit P-TEFb kinase activity. Hexim1/7SK/P-TEFb complexes were formed as in panel (A) with either full-length 7SK RNA or 7SK reconstituted in trans and assayed for P-TEFb kinase activity by phosphorylation of GST-CTD. (C) Hexim1 specifically binds the 7SK(24–87) hairpin RNA in vivo. HeLa cells were transiently co-transfected with plasmids expressing flag-Hexim1 and 7SK(24–87) hairpin. Flag-Hexim1 complexes were immunoprecipitated from cell extracts. RNA was phenol extracted from total cell extracts and from pellets and analyzed by northern blot. The higher band corresponds to endogenous 7SK RNA and the lower band to the 7SK(24–87) hairpin.

To confirm the functionality of our in vitro P-TEFb/Hexim1/7SK RNA complexes, we tested their ability to inhibit P-TEFb kinase activity. P-TEFb was incubated in the presence or absence of Hexim1 and 7SK and tested for phosphorylation of purified GST-CTD with radiolabeled ATP (Figure 7B). As shown above, when both Hexim1 and 7SK were present, the kinase activity of P-TEFb was almost completely abolished. Similarly, substituting wild-type 7SK with reconstituted 4-thioU-labeled 7SK RNA in trans also abolished P-TEFb activity. This result confirms that complexes formed with the artificial 7SK RNA in trans retain the same ability to inhibit P-TEFb as those formed with wild-type 7SK RNA.

Hexim1 specifically interacts with the 7SK(24–87) hairpin RNA in vivo

To confirm the functional relevance of the 7SK(24–87) hairpin, we examined its binding to Hexim1 in vivo. For these experiments, we designed an expression vector with the sequence of 7SK(24–87) expressed under a human 7SK promoter. This construct was co-transfected into HeLa cells with an expression vector for flag-tagged Hexim1. Flag-Hexim1 was immunoprecipitated from cell extracts and co-purified RNA was phenol-extracted and analyzed by northern blot (Figure 6C). Flag-Hexim1 immunoprecipitated not only endogenous 7SK, but also the 7SK(24–87) hairpin. This result shows that 7SK(24–87) hairpin RNA interacts with Hexim1 in vivo as well as in vitro. To confirm the specificity of this interaction, we used an RNA sequence mutated at positions 81–87, which prevented hairpin formation. Flag-Hexim1 did not interact with this mutant RNA, confirming the specificity of the interaction between Hexim1 and the 7SK(24–87) hairpin.

Discussion

Here, we present direct evidence from photo-cross-linking studies that Hexim1 interacts with the 24–87 region of 7SK RNA, both in the context of a 7SK hairpin or a complete RNA reconstituted in trans. The importance of this 7SK region for Hexim1 binding has previously been shown (33), but those results did not directly demonstrate the sites of interaction between 7SK RNA and Hexim1.

The cross-link site on the 7SK RNA was mapped by partial alkaline hydrolysis and confirmed by mutagenesis to position U30, which is predicted to be in the double-stranded region of the helix (41). The involvement of U30 in base pairing could explain the relatively low efficiency observed for RNA-protein cross-linking (38). Nonetheless, these results indicate that Hexim1 interacts with U30 via making contacts in the major groove of the helix because 4-thio group is positioned in the major groove of double helical RNA (38).

The cross-link site on Hexim1 was identified by NTCB and trypsin mapping to span between residues 196 and 220. This region of Hexim1 is close to, but outside its basic domain (residues 150–177), which was shown to be necessary for RNA binding (29,30). This result is interesting because it suggests that regions outside the basic domain of Hexim1 can also be involved in making contacts with 7SK RNA. Our mapping of the cross-link site was narrowed to residues 210–220 using GST-Hexim1 fusion proteins and Hexim1 deletion mutants. The cross-link of 7SK to residues 209–220 of Hexim1 is interesting because this region is close to the PYNT motif (residues 202–205), which has been shown to be important for interaction with CycT1 (29). In the absence of RNA, an acidic region of Hexim1 interacts with the basic RNA-binding region, resulting in a conformation that masks the PYNT motif and prevents Hexim1 binding to P-TEFb (32). Binding of 7SK RNA to the basic region of Hexim1 releases the acidic domain and unmasks the PYNT motif, allowing Hexim1 to bind CycT1. Presence of the cross-link near the PYNT motif suggests that this region of Hexim1 could be important for both 7SK binding and CycT1 binding. Indeed, we observe that deletion of 210–220 has a small but significant effect on RNA binding and on the ability of Hexim1 to inhibit P-TEFb kinase activity.

This mechanism is reminiscent of the Tat/TAR/P-TEFb complex, where the Tat interacts with both TAR RNA and CycT1. Indeed, the Tat-CycT1 protein complex was previously shown to bind TAR RNA in a highly cooperative manner (36,37). Likewise, the binding of P-TEFb to 7SK has been shown to depend on the binding of Hexim1 to 7SK (14,29). Another example is CycT1, whose residues 255–333 have been shown to contain both its 7SK-binding site (22) and the Tat/TAR-binding region (36), suggesting that CycT1 binds both RNAs in a similar fashion. This possibility is supported by the mutually exclusive binding of CycT1 to Tat and to Hexim1 (19,20). More structural studies are required to determine the extent of similarity between the interactions in these two complexes.

Despite these similarities, the 7SK and Tat/TAR complexes have many differences. For instance, Hexim1 and P-TEFb have been strongly suggested to interact with different regions of 7SK (33). The 3′-end hairpin of 7SK, which happens to have a structure very similar to that of TAR, was shown to be necessary for P-TEFb binding. However, P-TEFb binding to a specific 7SK region has not been directly demonstrated, because P-TEFb does not bind 7SK in the absence of Hexim1. Cross-linking experiments in the full 7SK/P-TEFb/Hexim1 complex would be useful to determine directly which portions of 7SK contact which residues on CycT1, and if these are the same residues that interact with TAR.

More than one Hexim1 and P-TEFb molecule bind to a single 7SK RNA (42,43) and an interesting question is whether two Hexim1 molecules bind together to the same RNA region. This possibility is supported by our gel-shift experiments, which showed two protein-RNA complexes of different size. This result also agrees with previous observations (29). However, Hexim1 can form dimers in the absence of RNA (43) so it is not clear if both Hexim1 molecules in a dimer interact with 7SK RNA. We observed only one 7SK RNA-Hexim1 cross-link, on the 24–54 strand. If two Hexim1 molecules were bound to neighboring portions of the 24–87 region, we would expect two cross-links, one for each protein. Another possibility is that two Hexim1 molecules bind to the RNA, but that only one contacts a uridine residue that is positioned favorably for cross-link.

To verify the specificity and functional significance of our experiments with the 7SK(24–87) hairpin, we reproduced our cross-link in the context of a full 7SK/Hexim1/P-TEFb complex. We showed that U30 of the 7SK RNA cross-links to Hexim1 in the full complex as it did with the minimal hairpin. From this result, we conclude that this cross-link of Hexim1 with the 24–87 hairpin corresponds to an interaction that is also present in the full complex. This experiment also shows that reconstituted 7SK RNA in trans can be used for site-directed cross-linking. This design could easily be adapted to study this complex with different site-directed cross-linking and probing methods.

Finally, we showed that the 7SK(24–87) hairpin interacts specifically with Hexim1 when expressed in vivo. This result agrees with a previous report that an RNA fragment corresponding to positions 1–111 of 7SK can interact with Hexim1 in vivo (33). Hexim1 has recently been shown to bind not only 7SK, but also other double-stranded RNAs in vivo and in vitro (44). That study also showed that a 7SK(10–48) hairpin was sufficient to bind Hexim1 in vitro. The structure of that hairpin differed from the secondary structure of the 10–48 region in full-length 7SK RNA based on chemical probing data (41). Alternate structures of 7SK probably co-exist in vivo, but it remains to be seen if the (10–48) hairpin structure exists in the context of the full 7SK sequence, and if so, which conformation is recognized in vivo by Hexim1. Unlike the present study, that of Li et al. (2007) did not test a 7SK(24–87) hairpin. Both hairpins likely have a structure that can be recognized in vitro by Hexim1. In fact, the structure of the 7SK(10–48) hairpin is similar to that of an inverted 7SK(24–87) hairpin. More studies are needed to determine the structure of the Hexim1-bound 7SK RNA. 7SK RNA was recently shown to bind to Tat protein, which competes with Hexim1 for binding to 7SK in vitro (17). In that case, Tat was also shown to bind region 10–48, which can form an alternative TAR-like structure.

In conclusion, our cross-linking data directly demonstrate that residues 210–220 of Hexim1 interact with U30 of 7SK RNA. Our results show that regions outside the basic domain of Hexim1 can be involved in RNA interactions. Clearly, much remains to be learned about the structure of 7SK RNA and its interactions with Hexim1, P-TEFb and other protein factors. Our cross-linking strategy can be a powerful tool to study RNA-protein interactions in these complexes. Using 7SK reconstituted in trans will facilitate site-directed cross-linking and chemical probing of 7SK structure and interactions, thus enhancing insight into the role of this small nuclear RNA in controlling gene expression.

Materials and Methods

In vitro transcription and RNA labeling

7SK RNA constructs were transcribed in vitro using synthetic DNA oligonucleotides (Integrated DNA Technologies) that encode the 7SK RNA sequences and have a 3′ segment complementary to the T7 transcription initiation site (5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAG-3′). The DNA template strand was annealed to an equimolar amount of a complementary strand corresponding to the T7 initiation site. RNA was transcribed using a MEGAshortscript T7 kit (Ambion). RNAs were 4-thioU labeled during transcription using a 2:1 molar ratio of UTP:4-thioUTP (TriLink Biotechnologies). In vitro transcribed RNA was purified by denaturing PAGE. For 5′-end labeling, RNAs were first 5′-dephosphorylated by incubating for 1 h at 37°C with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (New England Biolabs). Dephosphorylated RNAs were 5′-end labeled with 0.5 μM [γ-32P]-ATP (6000 Ci/mmol) (Perkin-Elmer) per 100 pmoles RNA by incubating with T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs). 5′-end labeled RNAs were purified on a denaturing gel, visualized by autoradiography, eluted from gels, and desalted using NucAway columns (Ambion). Hairpin or duplex RNAs were annealed by heating for 2 min at 85°C and slow cooling to room temperature. Full-length 7SK RNA was transcribed in vitro using linearized pH7SK (a gift from Dr. Olivier Bensaude), which contains the 7SK sequence under control of the T7 promoter.

Purification of 6xHis-tagged Hexim1

6xHis-tagged Hexim1 was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) using plasmid pET21d-Hexim1 (a gift from Dr. Olivier Bensaude). His-tagged protein expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG for 3 h at 30°C. Bacteria were sonicated in PBS containing 1% Triton X-100, 50 μg/ml PMSF and 5 mM imidazole. Bacterial lysate was centrifuged 30 min at 20 000g, supernatant was collected, and its NaCl concentration adjusted to 750 mM. The supernatant was incubated for 1 h at 4°C with 1 ml of Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen) equilibrated with lysis buffer. After incubation, flow through was collected, and resin was washed with 10 ml of buffer 1 (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.8, 500 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 50 μg/ml PMSF and 10 mM imidazole), followed by wash with 10 ml of buffer 2 (same as buffer 1, but 100 mM NaCl). The column was eluted with 0.5 ml fractions of buffer 2 containing 100, 200, 300 and 500 mM imidazole. Fractions shown by SDS-PAGE analysis to contain pure Hexim1 were dialyzed in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.8, 100 mM NaCl, 15% glycerol and stored at −80°C.

Biotinylation of Hexim1 by intein-mediated protein ligation

Hexim1 was expressed as an intein-fusion protein using the Impact-CN system (New England Biolabs). The coding sequence of Hexim1 was amplified by PCR using plasmid pET21d-Hexim1 (a gift from Dr. Olivier Bensaude) as a template. Primers were Hex1-A78G: 5′-GGTGGTCCATGGCCGAGCCATTCTTGTCAGAATATCAACACCAGCCTCAAACTAGCAACTGTACAGGTGCTGCTGCTGTCCAGGAGGAGCTGAACCC-3 ′ and Hex1-SapI: GGTGGTTGCTCTTCCGCACCCGTCTCCAAACTTGGAAAGCGGCGCTCG. These primers contained NcoI- and SapI-restriction sites, respectively (underlined). The Hex-A78G primer introduced a silent mutation at position 78 to eliminate a SapI-restriction site in the sequence of Hexim1. Primer Hex1-SapI also introduced an extra glycine residue at the end of the Hexim1 sequence to increase the efficiency of intein self-cleavage. The PCR product was cloned into pTYB3 (New England Biolabs) using the NcoI- and SapI-restriction sites, thus fusing the intein/chitin binding-domain tag at the Hexim1 C-terminus. Ligation reactions were transformed into E. coli DH5α chemically competent cells (Invitrogen). Clones were confirmed by sequencing and transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) (Novagen) for protein expression.

Hexim1-intein fusion proteins were induced by treating cells with 0.5 mM IPTG overnight at 15°C. Cells were disrupted by sonicating in 10 ml of column buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.9, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 50 μg/ml PMSF). Lysates were centrifuged at 20,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. Supernatants were added to 0.5 ml chitin beads (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in column buffer and mixed with agitation for 1h at 4°C. After incubation, flow through was collected and beads were washed with 10 ml of column buffer, followed by washing with 2 ml ligation buffer (same as column buffer, except 100 mM NaCl and 50 mM 2-mercaptoethanesulfonate sodium salt (Sigma)). Finally, the column was washed with 1 ml ligation buffer containing 2 mM of biotin-labeled peptide CG(K-biotin)G which was synthesized according to standard Fmoc peptide synthesis protocols (45,46). When only a small amount of buffer remained in the column the flow was stopped, and the column was incubated overnight at room temperature.

The cleaved Hexim1 product was eluted with 2 ml of elution buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.9, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 50 μg/ml PMSF), and 0.5 ml fractions were collected and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Fractions containing Hexim1 were dialyzed in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.8, 100 mM NaCl, 15% glycerol, and stored at −80°C. The presence of biotin on Hexim1 was detected by western blotting. Samples were run on a 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad), and blotted with streptavidin conjugated to HRP (GE Healthcare) diluted 1:10000 in 2.5% non-fat dry milk in TBST. Detection was done using SuperSignal West Dura reagent (Pierce) in a LAS-3000 luminometer (Fujifilm).

Purification of GST-Hexim1 fusion proteins

Short portions of Hexim1 (amino acids 150–177, 150–196, 150–209 and 150–220) were amplified by PCR using pET21d-Hexim1 as a template and cloned into pQET-4T2 using EcoRI and XhoI restriction sites. Fusion protein were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) with 0.5 mM IPTG for 16h at 15 °C. Cells were disrupted by sonicating in 10 ml of lysis buffer (1x PBS + 2mM EDTA, 1mM DTT and 50 μg/ml PMSF). Lysates were centrifuged at 20,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. Supernatants were added to 0.5 ml glutathione sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in lysis buffer and mixed with agitation for 2h at 4°C. After incubation, flow through was collected and beads were washed with 10 ml of wash buffer (1x PBS + 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT and 50 μg/ml PMSF) and 10 ml of TZ buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM KCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 12.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT). Elution was done with 20 mM glutathione in TZ buffer. Fractions containing GST fusion protein were dialyzed in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.8, 100 mM NaCl, 15% glycerol, and stored at −80°C.

Purification of P-TEFb

Recombinant baculoviruses for expression of P-TEFb were a gift from Dr. David H. Price (47). SF9 insect cells (eight 150-cm2 flasks at a confluence of 70%) were infected with baculovirus for 4 days at 27°C. Cells were harvested and P-TEFb was purified using the baculogold 6xHis purification kit (BD Pharmingen) following manufacturer’s instructions. Elution fractions shown by SDS-PAGE to contain pure CDK9 and CycT1 were dialyzed in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.8, 100 mM NaCl, 15% glycerol and stored at −80°C.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays

To examine 7SK RNA binding to Hexim1, 1 nM of 5′-end labeled RNA was incubated with 0 to 50 nM purified 6xHis-Hexim1 in 20 μl 1X binding buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 60 mM KCl, 6 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 5 mM DTT, 0.01% NP-40, 500 ng polyIC). Reactions were incubated for 1h at 4 C. RNA-protein complexes were separated from unbound RNA by native 6% PAGE (0.5X Tris-glycine) containing 0.01% NP-40. Gels were run at 300 V for 2 h at 4°C and bands were visualized by phosphorimaging.

4-thioU photo-cross-linking

7SK RNA duplexes containing 4-thioU were incubated for 1h at 4 °C with or without 50 nM 6xHis-Hexim1 in 50 μl 1X binding buffer. The reaction products were UV-irradiated at 4 C in polystyrene Petri dishes (to filter wavelengths below 300 nm) using an Ultra-Lum multi-wavelength transilluminator set to UVA (>320 nm). As a control, cross-linked products were incubated with 20 μg proteinase K (Ambion) for 20 min at 37 °C. Cross-linked products were purified by combining 10 individual cross-linking reactions, separated by 5% denaturing PAGE, and visualized by autoradiography. Cross-linked products were cut from gels, eluted in 300 mM NaOAc pH 6.8, 1 mM EDTA, 0.2% SDS, and recovered by n-butanol extraction.

Partial alkaline hydrolysis

RNA was partially hydrolyzed in 10 μl of 50 mM NaHCO3/Na2CO3 pH 9.2 containing 1 μg yeast RNA and 6 pg of 5-end labeled 7SK(24–54) RNA strand or purified cross-link product and incubated for 15 min at 85 C. Partial RNaseT1 digestion was done in 1X sequencing buffer (Ambion) containing 1 μg yeast RNA, 6 pg of 5-end labeled 7SK(24–54) RNA strand and 1–10 units of RNase T1 (Ambion), and incubated for 15 min at room temperature. Samples were separated by 20% denaturing PAGE and visualized by phosphorimaging.

Protein mapping

Hexim1-biotin or cross-linked products were cleaved at cysteine residues in 20 μl of 210 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.8, 2M urea, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol. Samples were incubated for 15 min at 37 °C, 2 μl of 2-nitro-5-thiocyanato-benzoic acid (NTCB, 10mg/ml in methanol) was added, and samples were incubated for 15 min at 37 °C. Finally, 1 μl of 1M NaOH was added, and samples were incubated another 20 min at 37 °C. Trypsin cleavage was done in 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 1 mM CaCl2, 5 mM DTT with 50 ng of sequencing grade trypsin (Promega), and incubated for 1 min on ice. All reactions were stopped by adding 10 μl 4X SDS loading buffer and snap-freezing. Samples were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE and analyzed by western blot using streptavidin-HRP as described above.

Kinase assays

Full-length 7SK or 7SK fragments corresponding to positions 1–54 and positions 55–331 were produced by in vitro transcription as described above and renatured in 1X binding buffer by heating at 85 °C, cooling to room temperature, and incubating 5 min on ice. Complexes were produced by mixing 1 pmol P-TEFb, 2 pmol Hexim1, and 2 pmol 7SK in 20 μl of 1X binding buffer (see above) and incubating 10 min at room temperature. Kinase activity of complexes was assayed by adding 2 pmoles purified GST-CTD and 50 μM of [γ-32P]-ATP (1 μCi). Samples were incubated 15 min at 30°C and reaction was stopped by adding SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Samples were resolved by 4–20% SDS-PAGE and visualized by phosphorimaging. Complexes were cross-linked as described above.

In vivo expression of 7SK(24–87) hairpin RNA

The promoter region of the 7SK RNA gene was amplified by PCR from human genomic DNA using a forward primer containing a PstI restriction site (underlined): 5′-TGGAGACTGCAGTATTTAGC and a reverse primer containing EcoRI and AvaI restriction sites (underlined): 5′-GGGCCCGAATTCGCCTCACATCCCGAGGTACCCAGGCGGCGCACAAGC. This PCR product was cloned into pUC19 using the PstI and EcoRI sites. Cassettes encoding the 7SK(24–87) wild-type and mutant sequences were then cloned into this vector using the AvaI and EcoRI sites. The oligonucleotide sequences for the wild-type cassette are: forward: 5′-TCGGGACATCTGTCACCCCATTGATCGCCAGGGTTGATTCGGCTGATCTGGCTGGCTAGGCGGGTGTCCCTTTCTTTTGACCCG; reverse: 5 ′-AATTCGGGTCAAAAGAAAGGGACACCCGCCTAGCCAGCCAGATCAGCCGAATCAACCCTGGCGATCAATGGGGTGACAGATGTC; and for the mutant cassette, forward: 5′-TCGGGACATCTGTCACCCCATTGATCGCCAGGGTTGATTCGGCTGATCTGGCTGGCTAGGCCCCACAGCCTTTCTTTTGACCCG; and reverse: 5′-AATTCGGGTCAAAAGAAAGGCTGTGGGGCCTAGCCAGCCAGATCAGCCGAATCAACCCTGGCGATCAATGGGGTGACAGATGTC. These vectors were transfected into HeLa cells with a vector expressing flag-Hexim1 (pAdRSV-FlagMAQ1, a gift from Dr. Olivier Bensaude). After 24 h, cells were lysed and flag-Hexim1 was immunoprecipitated from lysates with EZview Red anti-flag M2 affinity gel (Sigma) following manufacturer’s instruction. RNA was recovered from supernatants and pellets by phenol extraction and analyzed by northern blot using a probe complementary to positions 24–45 of 7SK RNA (5′-GATCAATGGGGTGACAGATGTC).

Acknowledgments

Plasmids pH7SK, pET21d-Hexim1, and pAdRSV-FlagMAQ1 were gifts from Dr. Olivier Bensaude. Recombinant baculoviruses for expression of P-TEFb were a gift from Dr. David H. Price. We also thank Siobhan O’Brien for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. FB held a fellowship from the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec (FRSQ). This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health to TMR.

References

- 1.Zhou Q, Yik JH. The Yin and Yang of P-TEFb regulation: implications for human immunodeficiency virus gene expression and global control of cell growth and differentiation. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006;70:646–659. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00011-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peterlin BM, Price DH. Controlling the elongation phase of transcription with P-TEFb. Mol Cell. 2006;23:297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ping YH, Rana TM. DSIF and NELF interact with RNA polymerase II elongation complex and HIV-1 Tat stimulates P-TEFb-mediated phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II and DSIF during transcription elongation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12951–12958. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006130200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ping YH, Rana TM. Tat-associated kinase (P-TEFb): a component of transcription preinitiation and elongation complexes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:7399–7404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.7399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang X, Gold MO, Tang DN, Lewis DE, Aguilar-Cordova E, Rice AP, Herrmann CH. TAK, an HIV Tat-associated kinase, is a member of the cyclin-dependent family of protein kinases and is induced by activation of peripheral blood lymphocytes and differentiation of promonocytic cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:12331–12336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu Y, Pe’ery T, Peng J, Ramanathan Y, Marshall N, Marshall T, Amendt B, Mathews MB, Price DH. Transcription elongation factor P-TEFb is required for HIV-1 tat transactivation in vitro. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2622–2632. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.20.2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barboric M, Nissen RM, Kanazawa S, Jabrane-Ferrat N, Peterlin BM. NF-kappaB binds P-TEFb to stimulate transcriptional elongation by RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell. 2001;8:327–337. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanazawa S, Soucek L, Evan G, Okamoto T, Peterlin BM. c-Myc recruits P-TEFb for transcription, cellular proliferation and apoptosis. Oncogene. 2003;22:5707–5711. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jang MK, Mochizuki K, Zhou M, Jeong HS, Brady JN, Ozato K. The bromodomain protein Brd4 is a positive regulatory component of P-TEFb and stimulates RNA polymerase II-dependent transcription. Mol Cell. 2005;19:523–534. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang Z, Yik JH, Chen R, He N, Jang MK, Ozato K, Zhou Q. Recruitment of P-TEFb for stimulation of transcriptional elongation by the bromodomain protein Brd4. Mol Cell. 2005;19:535–545. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen VT, Kiss T, Michels AA, Bensaude O. 7SK small nuclear RNA binds to and inhibits the activity of CDK9/cyclin T complexes. Nature. 2001;414:322–325. doi: 10.1038/35104581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang Z, Zhu Q, Luo K, Zhou Q. The 7SK small nuclear RNA inhibits the CDK9/cyclin T1 kinase to control transcription. Nature. 2001;414:317–322. doi: 10.1038/35104575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiu YL, Cao H, Jacque JM, Stevenson M, Rana TM. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication by RNA interference directed against human transcription elongation factor P-TEFb (CDK9/CyclinT1) Journal of virology. 2004;78:2517–2529. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.5.2517-2529.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yik JH, Chen R, Nishimura R, Jennings JL, Link AJ, Zhou Q. Inhibition of P-TEFb (CDK9/Cyclin T) kinase and RNA polymerase II transcription by the coordinated actions of HEXIM1 and 7SK snRNA. Mol Cell. 2003;12:971–982. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00388-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michels AA, Nguyen VT, Fraldi A, Labas V, Edwards M, Bonnet F, Lania L, Bensaude O. MAQ1 and 7SK RNA interact with CDK9/cyclin T complexes in a transcription-dependent manner. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:4859–4869. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.14.4859-4869.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He N, Pezda AC, Zhou Q. Modulation of a P-TEFb functional equilibrium for the global control of cell growth and differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:7068–7076. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00778-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sedore SC, Byers SA, Biglione S, Price JP, Maury WJ, Price DH. Manipulation of P-TEFb control machinery by HIV: recruitment of P-TEFb from the large form by Tat and binding of HEXIM1 to TAR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:4347–4358. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barboric M, Yik JH, Czudnochowski N, Yang Z, Chen R, Contreras X, Geyer M, Matija Peterlin B, Zhou Q. Tat competes with HEXIM1 to increase the active pool of P-TEFb for HIV-1 transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:2003–2012. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fraldi A, Varrone F, Napolitano G, Michels AA, Majello B, Bensaude O, Lania L. Inhibition of Tat activity by the HEXIM1 protein. Retrovirology. 2005;2:42. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-2-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schulte A, Czudnochowski N, Barboric M, Schonichen A, Blazek D, Peterlin BM, Geyer M. Identification of a cyclin T-binding domain in Hexim1 and biochemical analysis of its binding competition with HIV-1 Tat. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24968–24977. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501431200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Contreras X, Barboric M, Lenasi T, Peterlin BM. HMBA Releases P-TEFb from HEXIM1 and 7SK snRNA via PI3K/Akt and Activates HIV Transcription. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e146. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen R, Yang Z, Zhou Q. Phosphorylated positive transcription elongation factor b (P-TEFb) is tagged for inhibition through association with 7SK snRNA. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:4153–4160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310044200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen R, Liu M, Li H, Xue Y, Ramey WN, He N, Ai N, Luo H, Zhu Y, Zhou N, et al. PP2B and PP1alpha cooperatively disrupt 7SK snRNP to release P-TEFb for transcription in response to Ca2+ signaling. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1356–1368. doi: 10.1101/gad.1636008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barrandon C, Bonnet F, Nguyen VT, Labas V, Bensaude O. The transcription-dependent dissociation of P-TEFb-HEXIM1-7SK RNA relies upon formation of hnRNP-7SK RNA complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:6996–7006. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00975-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Herreweghe E, Egloff S, Goiffon I, Jady BE, Froment C, Monsarrat B, Kiss T. Dynamic remodelling of human 7SK snRNP controls the nuclear level of active P-TEFb. Embo J. 2007;26:3570–3580. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He N, Jahchan NS, Hong E, Li Q, Bayfield MA, Maraia RJ, Luo K, Zhou Q. A La-related protein modulates 7SK snRNP integrity to suppress P-TEFb-dependent transcriptional elongation and tumorigenesis. Mol Cell. 2008;29:588–599. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krueger BJ, Jeronimo C, Roy BB, Bouchard A, Barrandon C, Byers SA, Searcey CE, Cooper JJ, Bensaude O, Cohen EA, et al. LARP7 is a stable component of the 7SK snRNP while P-TEFb, HEXIM1 and hnRNP A1 are reversibly associated. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:2219–2229. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Markert A, Grimm M, Martinez J, Wiesner J, Meyerhans A, Meyuhas O, Sickmann A, Fischer U. The La-related protein LARP7 is a component of the 7SK ribonucleoprotein and affects transcription of cellular and viral polymerase II genes. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:569–575. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michels AA, Fraldi A, Li Q, Adamson TE, Bonnet F, Nguyen VT, Sedore SC, Price JP, Price DH, Lania L, et al. Binding of the 7SK snRNA turns the HEXIM1 protein into a P-TEFb (CDK9/cyclin T) inhibitor. Embo J. 2004;23:2608–2619. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yik JH, Chen R, Pezda AC, Samford CS, Zhou Q. A human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat-like arginine-rich RNA-binding domain is essential for HEXIM1 to inhibit RNA polymerase II transcription through 7SK snRNA-mediated inactivation of P-TEFb. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5094–5105. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.12.5094-5105.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blazek D, Barboric M, Kohoutek J, Oven I, Peterlin BM. Oligomerization of HEXIM1 via 7SK snRNA and coiled-coil region directs the inhibition of P-TEFb. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:7000–7010. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barboric M, Kohoutek J, Price JP, Blazek D, Price DH, Peterlin BM. Interplay between 7SK snRNA and oppositely charged regions in HEXIM1 direct the inhibition of P-TEFb. Embo J. 2005;24:4291–4303. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Egloff S, Van Herreweghe E, Kiss T. Regulation of polymerase II transcription by 7SK snRNA: two distinct RNA elements direct P-TEFb and HEXIM1 binding. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:630–642. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.2.630-642.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Favre A, Saintome C, Fourrey JL, Clivio P, Laugaa P. Thionucleobases as intrinsic photoaffinity probes of nucleic acid structure and nucleic acid-protein interactions. Journal of photochemistry and photobiology. 1998;42:109–124. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(97)00116-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richter SN, Belanger F, Zheng P, Rana TM. Dynamics of nascent mRNA folding and RNA-protein interactions: an alternative TAR RNA structure is involved in the control of HIV-1 mRNA transcription. Nucleic acids research. 2006;34:4278–4292. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richter S, Ping YH, Rana TM. TAR RNA loop: a scaffold for the assembly of a regulatory switch in HIV replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:7928–7933. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122119999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richter S, Cao H, Rana TM. Specific HIV-1 TAR RNA loop sequence and functional groups are required for human cyclin T1-Tat-TAR ternary complex formation. Biochemistry. 2002;41:6391–6397. doi: 10.1021/bi0159579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Z, Rana TM. RNA conformation in the Tat-TAR complex determined by site-specific photo-cross-linking. Biochemistry. 1996;35:6491–6499. doi: 10.1021/bi960037p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chan YL, Correll CC, Wool IG. The location and the significance of a cross-link between the sarcin/ricin domain of ribosomal RNA and the elongation factor-G. J Mol Biol. 2004;337:263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Samaha RR, Joseph S, O’Brien B, O’Brien TW, Noller HF. Site-directed hydroxyl radical probing of 30S ribosomal subunits by using Fe(II) tethered to an interruption in the 16S rRNA chain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:366–370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wassarman DA, Steitz JA. Structural analyses of the 7SK ribonucleoprotein (RNP), the most abundant human small RNP of unknown function. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:3432–3445. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.7.3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dulac C, Michels AA, Fraldi A, Bonnet F, Nguyen VT, Napolitano G, Lania L, Bensaude O. Transcription-dependent association of multiple positive transcription elongation factor units to a HEXIM multimer. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30619–30629. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502471200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Q, Price JP, Byers SA, Cheng D, Peng J, Price DH. Analysis of the large inactive P-TEFb complex indicates that it contains one 7SK molecule, a dimer of HEXIM1 or HEXIM2, and two P-TEFb molecules containing Cdk9 phosphorylated at threonine 186. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:28819–28826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502712200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li Q, Cooper JJ, Altwerger GH, Feldkamp MD, Shea MA, Price DH. HEXIM1 is a promiscuous double-stranded RNA-binding protein and interacts with RNAs in addition to 7SK in cultured cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:2503–2512. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang J, Tamilarasu N, Hwang S, Garber ME, Huq I, Jones KA, Rana TM. HIV-1 TAR RNA enhances the interaction between Tat and cyclin T1. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:34314–34319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006804200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tamilarasu N, Zhang J, Hwang S, Rana TM. A new strategy for site-specific protein modification: analysis of a Tat peptide-TAR RNA interaction. Bioconjugate chemistry. 2001;12:135–138. doi: 10.1021/bc000104z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peng J, Marshall NF, Price DH. Identification of a cyclin subunit required for the function of Drosophila P-TEFb. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13855–13860. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]