Abstract

PURPOSE

To investigate tissue changes observed in diffusion – weighted imaging (DWI) and its relation to contrast imaging, thermal dosimetry, and changes in the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) after MRI – guided focused ultrasound surgery (MRgFUS) of uterine fibroids.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Imaging data were analyzed from 45 fibroids in 42 women treated with MRgFUS. The areas of the hyperintense regions in DWI and of nonperfused regions in T1 – weighted contrast enhanced imaging (both acquired immediately after treatment) were compared to each other and to thermal dosimetry based estimates. Changes in ADC were also calculated.

RESULTS

Hyperintense regions were observed in 35/45 fibroids in DWI. When present, the areas of these regions were comparable on average to the thermal dose estimates and to the nonperfused regions, except for in several large treatments in which the nonperfused region extended beyond the treated area. ADC increased in 19 fibroids and decreased in the others.

CONCLUSION

DWI changes, which includes changes in both in T2 and ADC, may be useful in many cases to delineate the treated region resulting from MRgFUS. However, clear DWI changes were not always observed, and in some large treatments, the extent of the nonperfused region was under – estimated. ADC changes immediately after MRgFUS were unpredictable.

Keywords: Uterine Fibroids, Focused Ultrasound Surgery, Diffusion Imaging

INTRODUCTION

Uterine leiomyomas, also referred to as fibroids and myomas, are the most common benign tumors of the female genital tract. Numerous therapeutic approaches are available including hormonal therapy, hysterectomy, hysteroscopic surgery, laparoscopic excision, myolysis and arterial embolization (1 – 4). A recent development in the management of myomas is the use of Magnetic Resonance guided Focused Ultrasound (MRgFUS) surgery, which has been tested in several clinical trials and has been approved for clinical use in several countries, including the United States (5 – 9).

With this technology, tissue volumes within the fibroid are thermally ablated using ultrasound exposures (sonications) delivered to multiple locations in order to provide symptom relief. The surgery is performed within a MRI unit, which provides real time guidance of the procedure. Throughout the treatment, MRI – based temperature mapping is employed to localize the ultrasound focal spot and monitor the induced temperature rise during each sonication. The temperature profile as a function of time is used online to estimate tissue areas that received a lethal thermal dose during treatment and therefore are expected to be thermally coagulated (10 – 14).

The size of the ablated volume is assessed immediately after treatment by the extent of tissue devascularization, which is visualized with contrast – enhanced T1 – weighted MR imaging. The nonperfused with MR – contrast agent regions are the areas where the blood flow is cut off due to treatment and could become necrotic. The efficacy of the treatment has been evaluated by symptom improvement, which has been shown to be related to the extent of the nonperfused regions (7, 15).

While thermal dose maps coincide with the nonperfused areas in animal studies (16 – 21), in uterine fibroids they can underestimate the size of the nonperfused areas, especially when large volumes are targeted (5, 6, 22, 23). This under – prediction could be due to occlusion of blood vessels within the fibroids that occurs during the procedure. If this is the case, it may be that more locations are sonicated than necessary. It may even be possible to purposely target blood vessels within the fibroid with just a few sonications and induce occlusion that results in large regions becoming nonperfused. This approach could potentially reduce the treatment time, which is currently a major limitation for MRgFUS. However, with such a strategy, one can no longer use thermal imaging to predict online what regions are ablated, and it may not be feasible to administer multiple injections of contrast agent.

Therefore, it would be desirable to have an alternative to contrast imaging that would not require the use of MR – contrast agent and could be applied at intervals during the treatment to follow the tissue ablation so that more locations than necessary are not sonicated. Such an alternative could be the use of diffusion – weighted imaging (DWI) and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) mapping, as has been suggested by Jacobs et al (24). Their assumption is that ablated uterine fibroid tissue exhibits characteristics similar to those of ischemic tissue. In that case, DWI and ADC mapping methods that have been successfully used for the diagnosis and management of cerebral ischemia could be of significant relevance (25 – 27). In addition the ADC values could provide information about the cellular environment that cannot be obtained by T1 – weighted imaging (24).

In their study, they observed hyperintense regions in DWI that were overlapping with the nonperfused regions and had an ADC value significantly lower than that before the treatment (24). However, no quantitative comparison of the actual size of these areas was performed. Therefore it was not clear if DWI coupled with ADC mapping could be used to evaluate the efficacy of the MRgFUS procedure instead of contrast – enhanced MRI. Moreover, the observed areas in the DWI images could represent the thermally coagulated regions.

The goal of our study was to investigate this issue for imaging acquired immediately after the MRgFUS procedure, when MR – contrast imaging is allowed. Our hypothesis was that DWI, which reflects changes in ADC and T2, could be useful as a surrogate for contrast imaging if the hyperintense areas on the DW images correspond to the nonperfused areas of the MR – contrast images. For that purpose, hyperintense areas in DWI, thermal dose maps and nonperfused regions acquired shortly after treatment were compared. We also examined the ADC maps to investigate their response to MRgFUS in a larger patient population than previously investigated (24).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

This is a retrospective analysis of data acquired from patients enrolled in phase III and post – approval clinical studies. The MRgFUS treatments were approved by our Institutional Review Board and complied with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Written informed consent about the treatment and the use of conscious sedation was obtained from all patients on the day of the procedure before entering the MRI suite.

Data from 46 women who underwent both MRgFUS and DWI were obtained. Thirty – two patients were from a multi – center non – randomized clinical trial where clinical outcomes have been reported (xx). The other 14 subjects were from an ongoing study to investigate the efficacy of the MRgFUS method on African – American women, who presents the highest incidence of leiomyomas among all ethnic groups (28, 29). Four patients had two fibroids and one patient had three fibroids that were treated with MRgFUS in one session. Patients and fibroids information is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients and Fibroids Information

| Datum | Value |

|---|---|

| Total number of patients | 46 |

| Patient age (years)* | 44.9 ± 4.2 (36 – 53) |

| Body mass index* | 26.7 ± 5.2 (21 – 39.8) |

| Race | |

| White | 31 |

| African-American | 14 |

| Other | 1 |

| No of treated fibroids | 52 |

| No of fibroids treated per patient | |

| One | 41 |

| Two | 4 |

| Three | 1 |

| Fibroid location | |

| Intramural | 45 |

| Submucosal | 3 |

| Subserosal | 4 |

Mean value ± standard deviation. Numbers in parentheses are the range.

Patients enrolled in the studies satisfied the following criteria: premenopausal women 18 years or older with no plans for future pregnancy, presence of symptomatic leiomyomas with a size of 2–10 cm, uterine size smaller than 24 weeks of pregnancy, no contraindications to standard MR imaging, no other pelvic or uncontrolled systemic disease and no excessive abdominal scarring. In addition, necrotic or degenerating fibroids (including those with fatty degeneration), as indicated by the screening MRI, were excluded.

All patients were evaluated by a physician and underwent screening MRI, usually about a week prior to the treatment. That was necessary to identify the number, size and location of fibroids. Moreover, it had to be verified that the fibroids could be reached by the ultrasound beam without harming any other organ or surrounding tissue. The screening MRI consisted of T2 – weighted fast spin – echo (FSE) and T1 – weighted fast spoiled gradient – echo (FSPGR) images of the pelvic area, acquired before and after intravenous administration of Gadopentetate dimeglumine (Magnevist, Berlex Laboratories, Wayne NJ; dose: 0.1mmol/Kgr). No DWI was performed in the screening examination.

MR-guided Focused Ultrasound Treatment

Each patient had to fast from midnight and shave the hair from the anterior abdominal wall down to the pubic crest. At the beginning of the procedure, a Foley catheter was inserted into the patient’s urinary bladder. Next intravenous conscious sedation (fentanyl citrate and midazolam hydrochloride) was administered to reduce pain or discomfort and to prevent patient motion.

All treatments were performed with the ExAblate 2000® MRgFUS device (InSightec, Haifa, Israel) that was coupled to an 1.5 T MRI unit (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) (5, 22). The patient was positioned on the treatment table lying prone and acoustical coupling between her anterior abdominal wall and the device was achieved with the use of a gel pad and degassed, deionized water. The table was advanced into the magnet bore and a series of T2 – weighted FSE images was acquired and transferred to the ablation system user interface. The radiologist selected the fibroid(s) to be treated and delineated the desired volume. Subsequently, the operators derived a safe treatment plan that spared the surrounding tissue and organs and outlined the skin. Special care was taken to avoid the presence of bowel loops and pelvic nerves on the ultrasound beam path. Subthreshold sonications were initially performed to calibrate the system and to determine the optimum sonication parameters of the treatment. MRI thermometry was used to assure that adequate thermal dose was delivered in each sonication location. Feedback from the patient was also taken into account in modifying the treatment parameters, especially when pain or heat sensation was reported.

All sonication locations were prescribed at one depth, in a single plane that was imaged immediately before and after the procedure with diffusion – weighted imaging that was performed with a line – scan diffusion imaging (LSDI) sequence (30 – 32). The duration of the DWI was approximately 1min for this slice. This sequence was chosen over standard single – shot echo – planar techniques because of its insensitivity to bulk motion and susceptibility artifacts. Moreover, a short TE can be achieved (due to comparably short read – out time), which is important if tissues with short T2, such as muscle, are investigated (30 – 32). A detailed comparison between EPI and LSDI can be found elsewhere (32).

The duration of the treatment was 2 – 4 hours, depending on the size and number of fibroids. Each sonication lasted 15 – 30 s and the temperature elevation was recorded every 5 s with a time series of single – plane, phase – difference FSPGR MR images for approximately 1 min (10). The imaging plane used during each sonication could be selected by the operator and was alternated between coronal imaging (imaging perpendicular to the ultrasound beam direction) and sagittal or axial imaging (imaging along the ultrasound beam direction). Phase wrapping was avoided by using a complex phase subtraction scheme and pair – wise image subtraction (17, 33). At the end of the treatment, within 5 min from LSDI imaging, coronal and sagittal T1 – weighted FSPGR images with and without MR – contrast agent were acquired to visualize the nonperfused region. Finally, axial T1 – weighted spin – echo images were also acquired. The parameters of all MRI sequences used for screening and treatment are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

MR Imaging Parameters

| Sequence | Repetition Time [msec] |

Echo Time [msec] |

Flip Angle [degrees] |

Echo Train Length |

Field of View [cm × cm] |

Matrix Size | Slice Thickness [mm] |

Bandwidth [kHz] |

Imaging Planes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2-weighted FSE (treatment planning) | 3000–6950 | 99–105 | 90 | 12–16 | 28 × 28 | 256 × 224 | 5 | 31 | Coronal, sagittal, transverse |

| T1-weighted FSPGR (contrast imaging) | 150–385 | 1.5–4.2 | 75/80 | NA | 20 × 20 | 256 × 160 | 5 | 31 | Coronal |

| T1-weighted SE | 500–800 | 8–14 | 90 | NA | 20 × 20 | 256 × 224 | 6 | 18 | Transverse |

| Phase-difference FSPGR (temperature mapping) | 40 | 20 | 30 | NA | 28 × 28 | 256 × 128 | 3 | 3.6 | Coronal, sagittal, transverse |

| LSDI (b = 700 s/mm2) | 2376 | 57 | 90 | NA | 28 × 21 | 128 × 96 | 5 | 3.9 | Coronal |

Image Analysis

The temperature analysis was the same as described earlier (xx). Briefly, the temperature rise as a function of time measured with MRI – based thermometry was used to calculate thermal dose maps for each sonication. A baseline body temperature of 37°C was added to the temperature rise for this calculation. The total accumulated thermal dose resulting from all sonications was calculated in the coronal treatment plane. When the thermometry was acquired in sagittal or axial planes to image the temperature distribution in depth, the dose in the coronal treatment plane was estimated from the mean temperature in a 3 mm wide strip centered at the treatment depth and assumed circular symmetry. Regions that reached a dose threshold of at least 18 equivalent min at 43°C, were segmented and the corresponding areas were measured (thermal dose estimates). This specific thermal dose threshold was chosen based on the results of previous studies on human subjects and animals (16, 22). Noise levels were estimated in a region of interest (11 × 11 voxels) selected in a non – heated area for each sonication. The average standard deviation in these regions was 2.3°C ± 0.8°C.

LSDI images were acquired with diffusion – weighting along three orthogonal directions with b factors of b0 = 5 s/mm2 and b1 = 700 s/mm2, selected to be in the range used earlier to evaluate MRgFUS of fibroids (24). Trace ADC maps were constructed for each pixel based on the diffusion related attenuation of the signal by the factor exp(−b1 ADC). Trace diffusion – weighted images were constructed retrospectively with the average ADC of the three orthogonal measurements and a b – factor of 1000 s/mm2. This choice of reconstructed b – value was the default reconstruction of the sequence and it was chosen for optimum region conspicuity (28). The ADC value pre and post treatment was calculated from the ADC maps by placing regions of interest (ROIs) on the treated and nontreated area of the fibroid. The size of the region was 1.2 cm × 1.2 cm. Contrast-enhanced T1 – weighted images acquired at the screening examination and after treatment were used to identify the treated areas and accurately position the ROIs on the ADC maps.

Regions in the fibroids affected by the MRgFUS treatment appeared hypointense in the MR – contrast enhanced T1 – weighted images, as a result of reduced perfusion. The same regions in the DW images, that presented signal intensity changes, appeared hyperintense. Following the procedure described in (16), these regions were manually segmented by a physicist (xx). No grading scheme was used. The DW images and contrast – enhanced images were segmented in separate groups and comparison was performed blind to the other imaging. The pre – treatment DW images were examined before segmentation to exclude any pre – existing slight hyperintense regions that were sometimes present. Analysis was performed by using Matlab software developed in – house (version 7.2, Mathworks, Natick, Massachusetts).

Because of small patient and table motion that occurs during the procedure and imaging sessions, we did not expect exact agreement between any two imaging data sets (thermal dosimetry, DWI, contrast MRI) for an individual patient. Assuming that this motion is random, however, we would expect the measurements of the areas to agree on average when considering all of the treatments, if they all were to accurately delineate the ablated region.

Statistical Analysis

The areas of the nonperfused regions in contrast MRI, the hyperintense regions in the DWI, and the thermal-dose estimates were compared with each other in pairs using a paired two – tailed Student’s t – test. The Bland – Altman method was also used for the statistical comparison and the ratio of the areas was plotted against the average of the two measurements (34). In addition, linear regression analysis was performed and correlation coefficients were calculated. Finally, the ADC values pre and post treatment were compared using a paired two – tailed Student’s t – test and the mean ADC values over different group of patients were calculated. All differences with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All quantities (areas, ratios, ADC values) are presented as mean ± standard deviation. The statistical analysis was performed with the Matlab statistical analysis toolbox (Mathworks, Natick, Massachusetts).

RESULTS

In total 52 fibroids (46 patients) were treated and 45 were analyzed (42 patients). Four fibroids were excluded because sufficient focal heating to produce thermal necrosis could not be achieved due to patient discomfort during sonications. In addition, two fibroids were excluded because DWI was not performed at the corresponding imaging plane (operator error). Finally, one fibroid was excluded due to a technical problem with the imaging coil that resulted in a large decrease in SNR. Signal intensity changes were not noted in any of the MR – contrast enhanced T1 – weighted and DW images acquired before the treatment that could be an indication of necrotic or degenerating areas within the fibroid.

In all 45 cases, nonperfused regions were detected after treatment and the thermal dose estimates were calculated from the temperature maps. A good correlation between the two methods was observed for small treatment areas, while the nonperfused regions were significantly larger than the dose estimates for larger areas. The mean ratio of the nonperfused area to thermal-dose area was 1.1 ± 0.5 (range: 0.1 – 0.6, limits of agreement: 0.1 – 2.1), the slope and the intercept of the least – square fit was 1.4 and −2.2 respectively and the correlation coefficient was 0.81. The difference between these two sets of measurements was statistically significant (p = 0.03).

Hyperintense areas in the DW images were observed in 35/45 cases and all of them were within the treated regions and overlapped with the nonperfused areas. The segmented areas were compared with the corresponding nonperfused ones and the thermal dose estimates. For small areas there was a good agreement among all methods; for larger areas however, the nonperfused regions were underestimated by the DW areas as was the case for the thermal dose. A case of a large nonperfused region is shown in figure 1. No significant difference was observed between these two sets of measurements (p = 0.07). The mean ratio of the nonperfused areas to DW areas was 1.1 ± 0.4 (range: 0.7 – 2.6, limits of agreement: 0.3 – 1.9), the slope and the intercept of the least – square fit was 1.2 and −0.5 respectively and the correlation coefficient was 0.83. Changes in T2 – weighted images were also often observed along with DWI changes, such as that shown in figure 1.

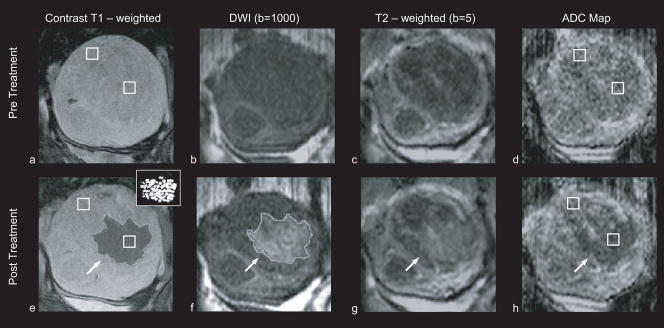

Figure 1. Patient 31 (52 years old, intramural leiomyoma).

Coronal images at the treatment plane, of one of the 35 cases in which hyperintense areas were observed in the diffusion weighted images. Regions of interest that were used to estimate the ADC values are indicated with white squares. All images are in the same scale. a: Contrast – enhanced T1 – weighted image acquired pre – treatment. b: DW image acquired pre – treatment. c: T2 – weighted image acquired pre – treatment. d: ADC map pre – treatment (ADC value: 1287 ± 258 × 10−6 mm2/sec). e: Contrast – enhanced T1 – weighted image acquired post – treatment. The area of the resulting nonperfused region (outlined) was 20.8 cm2. The thermal dose estimate calculated from the temperature maps is shown in the inset figure, at the upper right corner. Areas that reached a thermal dose of 240 min are grey and areas that reached a thermal dose of 18 min are white. The area of the region with a thermal dose exceeding 18 min at 43°C was 14.7 cm2. f: DW image acquired post – treatment. The area of the resulting hyperintense region (outlined) was 22.8 cm2. g: T2 – weighted image acquired post – treatment, the affected area appears hyperintense h: ADC map post - treatment, the affected area appears hypointense (ADC value: 923 ± 175 × 10−6 mm2/sec).

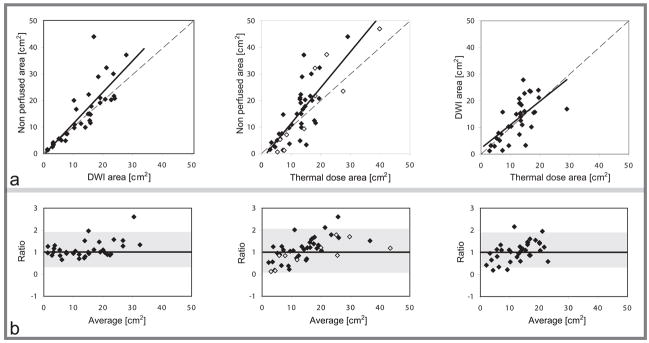

Good agreement was observed on average between the hyperintense areas in the DWI and the corresponding thermal dose ones. Statistically, no significant difference was observed between these two sets of measurements (p = 0.4). The mean ratio was 1.1 ± 0.5 (range: 0.2 – 2.2, limits of agreement: 0.1 – 2.1), the slope and the intercept of the least – square fit was 0.9 and 2.2 respectively, and the correlation coefficient was 0.65. Examples of the segmentation for six treated fibroids are shown in figure 2 and the results of the linear regression analysis and the Bland – Altman graphs for all of the fibroids are depicted in figure 3.

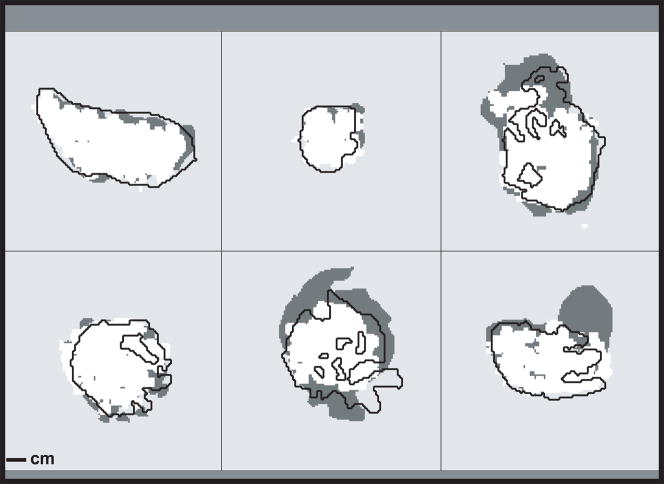

Figure 2.

Maps showing nonperfused regions (dark gray), regions that reached a thermal dose of at least 18 min at 43°C (white), and that were hyperintense in DWI (black line) for six fibroids treated with MRgFUS. Note that the images were not originally perfectly aligned due to small patient motion that occurred after the treatment was finished. They are aligned here to illustrate the differences in sizes of the different metrics.

Figure 3.

a: Comparison of the ablated areas predicted with contrast enhanced T1-weighted imaging (nonperfused area), DWI (DWI area) and MR thermometry (thermal dose area). Dashed lines indicate unity. Solid lines are linear regression of the data. From left to right: Nonperfused – DWI areas (y = 1.2× − 0.5, r = 0.83), nonperfused – thermal dose areas (y = 1.4x − 2.4, r = 0.81), DWI – thermal dose areas (y = 0.9x + 2.2, r = 0.65). In the graph of nonperfused - thermal dose areas, the cases with no signal intensity changes in the DW images are depicted with open circles. b: Corresponding Bland – Altman plots of the ratio of the two area measurements as a function of the average of the two measurements. Limits of agreement are shown with shaded areas (mean ratio ± 1.96 standard deviations).

In the most of the fibroids, signal intensity changes could be clearly seen in the ADC maps within the treated region. However, these changes were not consistent, as some showed a decrease in ADC and others an increase. Moreover, a few of them showed no apparent change at all. For this reason, the ADC maps were not segmented. This variation was also seen in the ROI analysis. The ADC value of the treated regions increased in 19 out of the 45 cases after MRgFUS treatment and decreased in the rest. More specifically, the ADC increased by 0 – 10% in 9 fibroids, 10 – 20% in 6 fibroids and 20 – 40% in 4 fibroids. The ADC decreased by 0 – 10% in 11 fibroids, 10 – 20% in 9 fibroids and 20 – 40% in 6 fibroids. Because of this variation, the overall difference between the mean pre- and pos – treatment ADC values (1220 ± 216 and 1191 ± 283 × 10−6 mm2/sec, respectively) was not significant (p = 0.36). The ADC findings for treated regions are summarized in table 3. No significant change in ADC value was observed in non – treated fibroid regions before and after (1210 ± 238 and 1232 ± 260 × 10−6 mm2/sec, respectively; p = 0.70) treatment or between treated and non – treated regions in the pre – treatment imaging (1220 ± 216 and 1210 ± 238 × 10−6 mm2/sec, respectively; p = 0.84).

Table 3.

Mean ADC value vs ADC change in treated areas pre/post MRgFUS treatment

| Mean ADC pre-treatment [mean ± standard deviation] in 10−6 mm2/sec | Mean ADC post-treatment [mean ± standard deviation] in 10−6 mm2/sec | # Fibroids | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADC change (%) | −40 to −20 | 1237 ± 157 | 897 ± 57*** | n = 6 |

| −20 to −10 | 1217 ± 147 | 1029 ± 136*** | n = 9 | |

| −10 to 0 | 1317 ± 347 | 1262 ± 333*** | n = 11 | |

| 0 to 10 | 1138 ± 74 | 1190 ± 81* | n = 9 | |

| 10 to 20 | 1134 ± 202 | 1294 ± 219*** | n = 6 | |

| 20 to 40 | 1250 ± 170 | 1646 ± 291** | n = 4 | |

| −40 to 0 | 1264 ± 249 | 1097 ± 272*** | n = 26 | |

| 0 to 40 | 1160 ± 144 | 1319 ± 250*** | n = 19 | |

| All | 1220 ± 216 | 1191 ± 283 | n = 45 |

Statistical significance of difference:

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001 compared to pre – treatment mean ADC value.

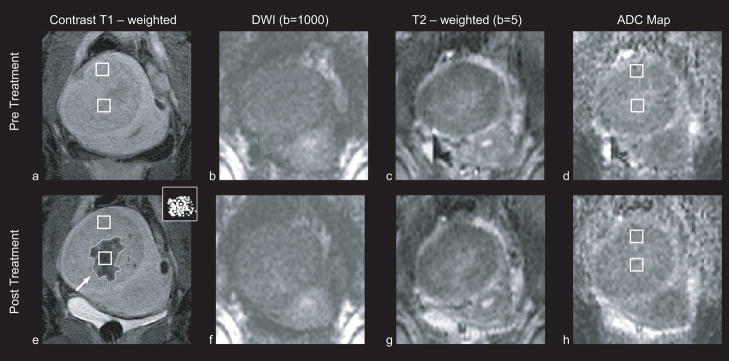

The remaining 10 cases, where no clearly discernible changes in the signal intensity at the DW images were observed, were further investigated. Examination of pre – treatment T2 – weighted images and T1 – weighted images pre and post contrast acquired in the screening exam and after MRgFUS, did not identify degenerated or abnormal area on these fibroids that might have had an effect on the DW imaging for these cases. Small treatment size could have influenced the outcome in some of these cases. In particular, four had treatments with an area less than 10 cm2, which may have been missed due to small patient motion or resolution limitations. In five other cases, some evident diffuse changes in the treated area were observed, but they could not be segmented due to low SNR (figure 4). And in one case changes were observed in both the ADC map (ADC increased by 13.8%) and the T2 – weighted image, but not in the DWI.

Figure 4. Patient 23 (53 years old, intramural leiomyoma).

Coronal images at the treatment plane of one of the 12 cases, in which no signal intensity changes were observed in the diffusion weighted images. Regions of interest that were used to estimate the ADC values are indicated with white squares. All images are in the same scale. a: Contrast enhanced T1 – weighted image acquired pre – treatment. b: DW image acquired pre – treatment. c: T2 – weighted image acquired pre – treatment. d: ADC map pre – treatment (ADC value: 1722 ± 217 × 10−6 mm2/sec). e: T1 – weighted image acquired post – treatment. The area of the resulting nonperfused region (outlined) was 7.1 cm2. The thermal dose estimate calculated from the temperature maps is shown in the inset figure, at the upper right corner. Areas that reached a thermal dose of 240 min are grey and areas that reached a thermal dose of 18 min are white. The area of the region with a thermal dose exceeding 18 min at 43°C was 8.5 cm2. f: DW image acquired post – treatment showing no clearly discernible changes in the signal intensity. g: T2 – weighted image acquired post – treatment. h: ADC map post – treatment (ADC value: 1625 ± 273 × 10−6 mm2/sec).

DISCUSSION

The areas of the nonperfused regions in contrast – enhanced MR imaging, the thermal-dose estimates calculated via MR thermometry, and the hyperintense regions in DWI were compared to each other after thermal ablation of uterine fibroids with MRgFUS. For small treatment areas, a good agreement was observed among all methods. However, in many cases with larger treatment volumes, the regions identified on the post-contrast T1 – weighted images were under-predicted regardless of the method used (DWI or MR thermometry).

Concerning the comparison of the thermal dose estimates and the nonperfused regions, this outcome is consistent with previous studies where it has also been verified with pathologic examination (5, 6, 22, 23). Although there are several mechanisms that could explain the difference in the outcome between small and large treatment areas, the most likely is vessel occlusion. More specifically, thermal coagulation of a vessel in the fibroid during MRgFUS could lead to downstream necrosis of a lesion larger than the prescribed area (5, 35). This might be more probable when the treatment volume is large, although the vascular pattern could also play a role (e.g. presence of main vessels in the ablated area).

On average, the hyperintense regions identified on the DW images were of comparable size to the corresponding thermal dose estimates and the nonperfused regions, having a better agreement with the latter. In several large treatments however, the size of the hyperintense DWI areas appeared to be closer to the thermal dose estimates than the nonperfused areas which sometimes extended into adjacent regions that were clearly not targeted with sonication (figure 3). This finding suggests that DWI acquired immediately after MRgFUS is sensitive to immediate tissue changes within the targeted region, but not necessarily to secondary effects that sometimes occur in non – targeted surrounding fibroid. Future imaging or histology studies will be needed to clarify what metric best predicts the necrosed tissue volume. It is not clear whether the nonperfused regions seen in contrast – enhanced MRI acquired immediately after MRgFUS indicate necrotic or ischemic tissue that could recover with time. In a previous study, Tempany et al (5) found significant differences between the volumes of nonperfused and pathologically abnormal tissue when the treated fibroids were examined after hysterectomy. Although, the number of the patients was small in that study, the difference between the two volume sets suggests that it is not clear which metric defines the regions within the fibroids that will ultimately be necrotic.

The DWI signal is affected by both changes in the ADC and T2. Indeed, both the ADC maps and T2 – weighted images confirmed the findings in DWI in most cases. However, no single parameter was perfect in detecting tissue changes. Both increasing and decreasing ADC values were observed after MRgFUS, perhaps reflective of differences in the tissue cellularity or other tissue properties. Changes in T2 – weighted images were also observed, but it was often difficult to distinguish thermally induced tissue changes from baseline heterogeneities in the fibroid. When DWI changes were present, they were often better delineated than the other measures, but clear changes were not present in 10/45 of the fibroids.

These ten cases, especially the six that did not have very small treatments, might suggest a limitation of using DWI to detect the effects of MRgFUS. As fibroids can present in MRI with a wide range of imaging properties (36), it may not be surprising that their response to MRgFUS ablation may also vary widely. It is also possible that changes in T2 – weighted images and ADC cancelled each other out in the DWI reconstruction. We suspect, however, that better results may have been obtained if the imaging parameters were optimized. Indeed, in five treatments, low – level, diffuse DWI changes were observed, but the SNR was insufficient to segment them. Such optimization was not performed here due to the limited time available during the treatments.

Another limitation of the study was that the imaging slices and matrices for the T1 – weighted imaging, DWI and thermometry were not exactly the same. As these patients were part of a larger clinical study, we were not permitted to change the imaging parameters, and only limited time was available for DWI. These imaging differences, along with our use of manual segmentation, may have resulted in some error in our measurements. However, we do not expect such errors to explain the large differences between the nonperfused regions and the other measurements that were observed for the large treatments. Another limitation of this study was only examining immediate tissue changes. Following such patients over longer periods may help explain some of our findings. It would also be of interest to create T2 maps to quantify the relative effects of T2 and ADC on the DWI changes. Finally, to precisely investigate the agreement between the different segmentations, a similarity measurement between the different segmentations should be performed. Comparison at such a fine level was not appropriate in this study due to the small motion that occurred over the course of the 3h treatments.

In conclusion, the results of this study suggest that hyperintense regions in DWI in uterine fibroids immediately after MRgFUS treatment are of comparable size to the nonperfused regions in contrast-enhanced imaging, but do not agree with them fully especially in large treatments. Moreover, DWI changes were not clearly evident in some cases. Thus, DWI does not appear yet to be a reliable surrogate for contrast imaging, if one wants to detect the nonperfused regions that can extend outside of the treated region. Nevertheless, it may be useful as a method to evaluate which regions were thermally coagulated.

Acknowledgments

NIH grants U41RR019703 & R01EB006867.

The clinical study was funded by InSightec (Haifa, Israel).

Footnotes

Authors who were not consultants to InSightec (Haifa, Israel), the manufacturer of the MRgFUS system (ExAblate 2000®), had control over the inclusion of any data that might have posed a conflict of interest for those authors who have been consultants to InSightec.

References

- 1.Stewart EA. Uterine fibroids. Lancet. 2001;357:293–298. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03622-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlos KJ, Nichols DH, Schiff I. Indications of hysterectomy. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:856–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199303253281207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Surgical alternatives to hysterectomy in the management of leiomyomas. ACOG practice bulletin #16, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Washington, DC. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pron G, Bennet J, Common A, Wall J, Asch M, Sniderman K. The Ontario Uterine Fibroid Embolization Trial. Part 2. Uterine fibroid reduction and symptom relief after uterine artery embolization for fibroids. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:120–127. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04538-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tempany CM, Stewart EA, McDannold N, Quade BJ, Jolesz FA, Hynynen K. MR imaging-guided focused ultrasound surgery of uterine leiomyomas: a feasibility study. Radiology. 2003;226:897–905. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2271020395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stewart EA, Gedroyc WMW, Tempany CMC, et al. Focused ultrasound treatment of uterine fibroid tumors: safety and feasibility of a noninvasive thermoablative technique. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:48–54. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart EA, Rabinovici J, Tempany CMC, et al. Clinical outcomes of focused ultrasound surgery for treatment of uterine fibroids. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.04.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smart OC, Hindley JT, Regan L, Gedroyc WG. Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone and magnetic-resonance-guided ultrasound surgery for uterine leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(1):49–54. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000222381.94325.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hesley GK, Felmlee JP, Gebhart JB, et al. Noninvasive treatment of uterine fibroids: early Mayo Clinic experience with magnetic resonance imaging-guided focused ultrasound. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(7):936–942. doi: 10.4065/81.7.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishihara Y, Calderon A, Watanabe H, Okamoto K, Suzuki Y, Kuroda K. A precise and fast temperature mapping using water proton chemical shift. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34(6):814–823. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peters RD, Hinks RS, Henkelman RM. Ex vivo tissue-type independence in proton-resonance frequency shift MR thermometry. Magn Reson Med. 1998;40:454–459. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910400316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuroda K, Chung AH, Hynynen K, Jolesz FA. Calibration of water proton chemical shift with temperature for noninvasive temperature imaging during focused ultrasound surgery. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1998;8(1):175–181. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880080130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Poorter J. Noninvasive MRI thermometry with the proton resonance frequency method: study of susceptibility effects. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34(3):359–367. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hynynen K, McDannold N. MRI guided and monitored focused ultrasound thermal ablation methods: a review of progress. Int J Hyperthermia. 2004;20:725–737. doi: 10.1080/02656730410001716597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stewart EA, Gostout B, Rabinovici J, Kim HS, Regan L, Tempany CMC. Sustained relief of leiomyoma symptoms by using focused ultrasound surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:279–287. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000275283.39475.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDannold NJ, Hynynen K, Wolf D, Wolf G, Jolesz FA. MRI evaluation of thermal ablation of tumors with focused ultrasound. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1998;8(1):91–100. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880080119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDannold NJ, King RL, Jolesz FA, Hynynen K. Usefulness of MR imaging-derived thermometry and dosimetry in determining the threshold for tissue damage induced by thermal surgery in rabbits. Radiology. 2000;216:517–523. doi: 10.1148/radiology.216.2.r00au42517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDannold N, Vykhodtseva N, Jolesz FA, Hynynen K. MRI investigation of the threshold for thermally induced blood-brain barrier disruption and brain tissue damage in the rabbit brain. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51(5):913–923. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDannold N, Hynynen K, Jolesz F. MRI monitoring of the thermal ablation of tissue: effects of long exposure times. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;13(3):421–427. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kangasniemi M, Diederich CJ, Price RE, et al. Multiplanar MR temperature-sensitive imaging of cerebral thermal treatment using interstitial ultrasound applicators in a canine model. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;16(5):522–531. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hazle JD, Stafford RJ, Price RE. Magnetic resonance imaging-guided focused ultrasound thermal therapy in experimental animal models: correlation of ablation volumes with pathology in rabbit muscle and VX2 tumors. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;15(2):185–194. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDannold N, Tempany CM, Fennessy FM, et al. Uterine Leiomyomas: MR imaging – based thermometry and thermal dosimetry during focused ultrasound thermal ablation. Radiology. 2006;240(1):263–272. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2401050717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hindley J, Gedroyc WM, Regan L, et al. MRI guidance of focused ultrasound therapy of uterine fibroids: early results. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183(6):1713–1719. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.6.01831713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacobs MA, Herskovits EH, Kim HS. Uterine fibroids: diffusion-weighted MR imaging for monitoring therapy with focused ultrasound surgery - preliminary study. Radiology. 2005;236:196–203. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2361040312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warach S, Gaa J, Siewert B, et al. Acute human stroke studied by whole brain echo planar diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol. 1995;37:231–241. doi: 10.1002/ana.410370214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crisostomo RA, Garcia MM, Tong DC. Detection of diffusion weighted MRI abnormalities in patients with transient ischemic attack: correlation with clinical characteristics. Stroke. 2003;34:932–937. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000061496.00669.5E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacobs MA, Mitsias P, Soltanian-Zadeh H, et al. Multiparametric MRI tissue characterization in clinical stroke with correlation to clinical outcome : Part 2. Stroke. 2001;32:950–957. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.4.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marshall LM, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, et al. Variation in the incidence of uterine leiomyoma among premenopausal women by age and race. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:967–973. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00534-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faerstein E, Szklo Me Rosenhein N. Risk factors for uterine leiomyoma: a practise-based case-control study I. African-American heritage, reproductive history, body size, and smoking. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153:1–10. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gudbjartsson H, Maier SE, Mulkern RB, Morocz IA, Patz S, Jolesz FA. Line scan diffusion imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1996;36:509–519. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maeda M, Maier SE, Sakuma H, Ishida M, Takeda K. Apparent diffusion coefficient in malignant lymphoma and carcinoma involving cavernous sinus evaluated by line scan diffusion-weighted imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;25:543–548. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kubicki M, Maier SE, Westin CF, et al. Comparison of single-shot echo-planar and line scan protocols for diffusion tensor imaging. Acad Radiol. 2004;11:224–232. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(03)00563-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chung AH, Hynynen K, Colucci V, Oshio K, Cline HE, Jolesz FA. Optimization of spoiled gradient-echo phase imaging for in vivo localization of a focused ultrasound beam. Magn Reson Med. 1996;36:745–752. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. lancet. 1986;1(8476):307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hynynen K, Colucci V, Chung A, Jolesz FA. Noninvasive artery occlusion using MRI guided focused ultrasound. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1996;22:1071–1077. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(96)00143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Funaki K, Fukunishi H, Funaki T, Sawada K, Kaji Y, Maruo T. Magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound surgery for uterine fibroids: relationship between the therapeutic effects and signal intensity of preexisting T2-weighted magnetic resonance images. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Feb;196(2):184.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]