Abstract

Radiotherapy plays a crucial role in the treatment of many malignancies; however, locoregional disease progression remains a critical problem. This has stimulated laboratory research into understanding the basis for tumor cell resistance to radiation and the development of strategies for overcoming such resistance. We know that some cell signaling pathways that respond to normal growth factors are abnormally activated in human cancer and that these pathways also invoke cell survival mechanisms that lead to resistance to radiation. For example, abnormal activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) promotes unregulated growth and is believed to contribute to clinical radiation resistance. Molecular blockade of EGFR signaling is an attractive strategy for enhancing the cytotoxic effects of radiotherapy and, as shown in numerous reports, the radiosensitizing effects of EGFR antagonists correlates with a suppression of the ability of the cells to repair radiation-induced DNA double strand breaks (DSBs). The molecular connection between the EGFR and its governance of DNA repair capacity appears to be mediated by one or more signaling pathways downstream of this receptor. The purpose of this review is to highlight what is currently known regarding EGFR-signaling and the processes responsible for repairing radiation-induced DNA lesions that explains the radiosensitizing effects of EGFR antagonists.

Keywords: DNA Repair, Receptor Tyrosine Kinases, Radiosensitivity, Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

Introduction

Cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract (UADT) are especially problematic in human health. Lung cancer is the leading cause of deaths due to cancer in the U.S. and a substantial world health problem in general [1]. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), another UADT tumor, is the fifth most common cancer in the U.S. [2]. For both of these cancers, the majority of patients present with advanced stages of disease and aggressive therapy is therefore required. Despite improvements in treatment strategies, including concurrent chemoradiotherapy, local/regional control remains a problem indicating that further advances in treatment are urgently needed. This situation has prompted extensive preclinical and clinical investigations into the biological reasons that would explain resistance to intensive combined-modality therapies. One of the important outcomes of this research has been the recognition that the majority of lung tumors, especially non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) representing 80% of lung cancers [3], and HNSCC tumors [4] abnormally express the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). EGFR is known to be overexpressed in a wide range of cancers including, in addition to NSCLC and HNSCC, ovarian, brain, breast, colorectal, kidney and pancreatic cancers [5]. EGFR is a member of a family of growth factor receptors collectively referred to as receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs). Other RTKs important in radiation oncology include IGF1R, c-Met, PDGF and VEGF.

Activation of EGFR in tumor cells stimulates a cascade of signal transduction pathways that regulate cell proliferation, differentiation, cell survival (apoptosis), cell cycle progression, and angiogenesis [6]. Understanding how these diverse characteristics downstream of EGFR stimulation are controlled at the molecular level is complicated by the fact that multiple signaling pathways can be involved including the Ras/Raf/MEK./ERK, PKC, STAT and PI3-K/AKT pathways [7, 8]. Moreover, each of these pathways has many different affected molecular endpoints. For example, the protein kinase, AKT, has been reported to have 100 different substrates complicating understanding of how this pathway regulates cell survival [9].

Based on the appreciation of EGFR’s role in cancer, several molecularly targeted agents have been developed to inhibit the activity of this growth factor receptor including gefitinib, erlotinib, and cetuximab [10]. Gefitinib and erlotinib are FDA-approved as single agents for advanced NSCLC and cetuximab is approved for advanced colon cancer in combination with cisplatin and for HNSCC in combination with radiation. Gefitinib and erlotinib are inhibitors of the tyrosine kinase activity of the EGFR and referred to as TKIs. Cetuximab is a monoclonal antibody that blocks the engagement of the natural ligand. Unfortunately, the improvement for NSCLC is relatively small overall because only a subset of patients respond to gefitinib and erlotinib when given as single agents and the majority of tumors progress. This is now understood to be due to the presence of activating mutations in the EGFR gene in the relatively small cohort of responding patients [11]. Therefore, there has been considerable interest in testing combinations of EGFR antagonists with conventional chemotherapy and radiotherapy with the goal of improving tumor response in the wider patient population.

In addition to their well-established clinical activities as single agents, gefitinib, erlotinib, and cetuximab are all, at least in preclinical models, radiosensitizers for a variety of tumor types including NSCLC and HNSCC. Based on this effect, cetuximab plus radiation has progressed through phase III clinical trials [12] to FDA approval for advanced HNSCC and phase I/II clinical trials assessing the efficacy of erlotinib plus radiation for NSCLC are currently in progress. A phase III trial assessing the combination of cetuximab and radiation plus chemotherapy is also ongoing in NSCLC. Numerous mechanisms have been proposed from pre-clinical investigations to explain how these EGFR inhibitors enhance radiation-response including effects on cell cycle distribution, apoptosis, necrosis, angiogenesis, tumor-cell motility, invasion, and metastatic capacity [13]. In addition, the radiosensitizing effects of all three of these EGFR antagonists correlates with a suppression of the ability of the cells to repair radiation-induced DNA double strand breaks (DSBs). However, the molecular mechanisms by which EGFR governs DNA repair capacity is complex and multi-factorial and appears to be mediated by one or more signaling pathways downstream of this receptor. The purpose of this review is to highlight what is currently known regarding EGFR-signaling and the processes responsible for repairing radiation-induced DNA lesions that explains the radiosensitizing effects of EGFR and other RTK antagonists.

Signaling and DNA Repair

As mentioned above, EGFR is known to signal through several downstream pathways. Of these, the PI3K/AKT and the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathways are the most extensively studied in the context of radiosensitization. Until just the past few years, the ability of these signal transduction pathways to influence the DNA repair processes that respond to ionizing radiation was unknown and not even suspected. However, the demonstrations that EGFR antagonists radiosensitize human cancer cells apparently by suppressing the repair of radiation-induced DNA lesions [14-19] stimulated detailed investigations into how signal transduction and DNA repair might interact. Ionizing radiation is thought to kill tumor cells by inducing lesions in DNA that unless faithfully and rapidly repaired interfere with subsequent mitotic divisions causing mitotic catastrophe and permanent cessation of cell division. The main types of DNA lesions induced by radiation include base damage, single strand breaks (SSBs), and double strand breaks (DSBs). Eukaryotic cells have very sophisticated enzymatic repair processes to eliminate these lesions following exposure to radiation and the base damage and SSBs are not considered lethal lesions, even though they are produced more frequently than DSBs, because they are faithfully and rapidly repaired. DSBs, on the other hand, do contribute to the lethal effects of ionizing radiation because they are repaired rather slowly and can lead to chromosome aberrations when rejoined incorrectly. The base damage and SSBs are repaired by the base excision repair pathway (BER). DSBs are repaired by two distinct repair mechanisms; referred to as non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination repair (HRR). The details of these repair systems have been reviewed elsewhere [20]. The NHEJ pathway is generally considered the major process that governs radiation-induced lethality in tumor cells [21] but HRR also contributes especially in cycling cells. Although there are multiple proteins involved in NHEJ, the DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit, DNA-PKcs, is a key enzyme. In response to DSBs, DNA-PKcs is activated by phosphorylation and together with its regulatory subunits, KU70 and KU80, stabilizes the break. This complex together with additional proteins namely Mre11, Rad50, Nbs1, XRCC4, and DNA ligase IV completes rejoining of the broken ends of DNA. Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) is another important repair protein that participates in governing the cell cycle checkpoints in response to DNA damage [22]. ATM dimmers are autophosphorylated in response to DSBs and ATM in turn then phosphorylates a number of other proteins involved in NHEJ, HRR and checkpoint signaling including the histone H2AX. Phosphorylated H2AX, γ-H2AX, can be detected by immunofluorescent staining as discrete foci under microscopy and such foci are commonly used as quantitative indicators of DSBs. ATM directly or indirectly controls the phosphorylation of other proteins involved in repair such as Rad51 and BRCA1. These proteins can also be visualized as foci at the sites of DSBs. Rad51 and BRCA1 have critical roles in HRR.

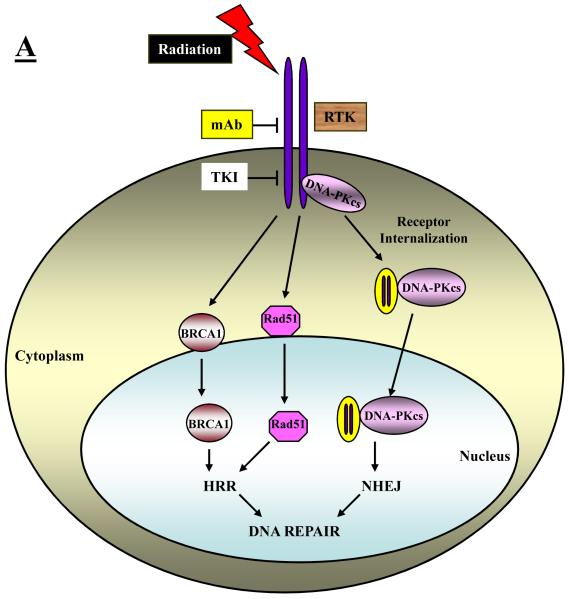

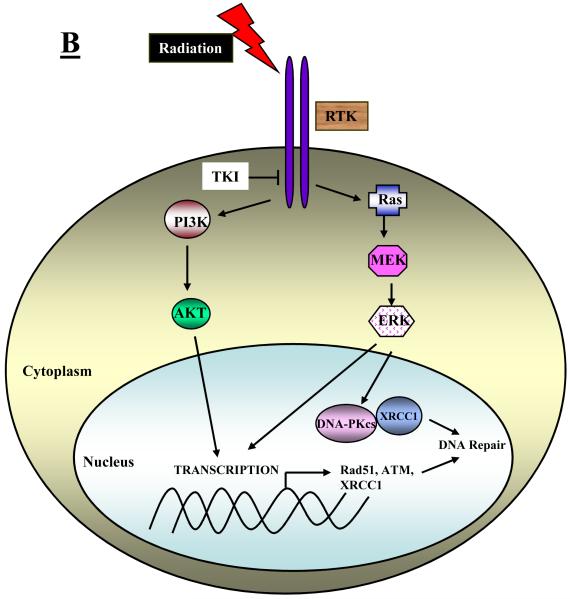

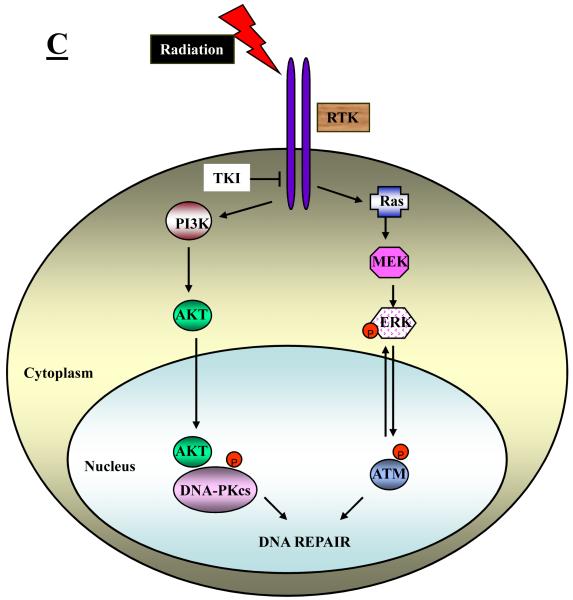

There are several ways in which EGFR and/or its downstream signaling effectors, PI3K/AKT and Ras/ERK, may affect elements of the BER, NHEJ and HRR repair processes. These include an ability of EGFR itself (or its downstream signaling) to affect the intracellular distribution of DNA repair proteins, the ability of signaling downstream of EGFR to affect the transcription of DNA repair genes, and the ability of AKT and ERK to directly or indirectly control the phosphorylation status of key repair proteins. These three possible mechanisms are depicted schematically in Figure 1A-1C.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of different mechanisms that have been identified to explain how RTK signaling intersects with and thereby regulates DNA repair processes. A: RTKs may directly or indirectly affect the intracellular distribution of DNA repair proteins. B: Signaling downstream of RTKs may affect the transcription of DNA repair genes or signal the physical association of repair proteins. C: Signaling downstream of RTKs may directly or indirectly control the phosphorylation and hence the activity of key repair proteins.

EGFR directly interacts with and affects the intracellular distribution of DNA repair proteins

The initial insight into a possible interaction between the EGFR and DNA repair was the discovery of a physical interaction between the EGFR protein itself and DNA-PKcs that was triggered by treating cells with a monoclonal antibody to EGFR (C225, cetuximab). Bandyopadhyay et al. [23] reported that confocal imaging revealed that DNA-PKcs was colocalized with EGFR in the cytoplasm. Treatment with C225 led to a 75% reduction of DNA-PK activity in the nucleus suggesting to the authors a possible role for EGFR signaling in maintaining the nuclear levels of DNA-PKcs and that interference in EGFR signaling may result in the impairment of DNA repair. Interestingly, Bandyopadhyay et al. [23] showed that the interaction of EGFR and DNA-PKcs could not be recapitulated using the EGFR kinase inhibitor tyrphostin A9 suggesting that an alteration in receptor dimerization and not a loss of receptor kinase activity is responsible for the interaction induced by the monoclonal antibody.

Following up on the report from Brandyopadhyay et al., in the context of irradiated cells, Huang and Harari [14] reported that the combination of C225 and radiation caused a redistribution of DNA-PKcs from the nucleus to the cytoplasm and suggested that since DNA-PKcs is critical for NHEJ a reduction in its nuclear levels could explain the radiosensitizing effects of C225. This interaction between EGFR and DNA-PKcs has been investigated in more detail and in the context of irradiated cells by Dittmann et al. [16] They report that ionizing radiation triggers a translocation of EGFR into the nucleus where it forms a physical interaction with DNA-PKcs correlating with radiation-induced DNA-PK activity. Pretreatment of cells with C225 prior to irradiation inhibited transport of EGFR into the nucleus and suppressed radiation-induced DNA-PK activity. These effects of C225 correlated with a radiosensitization of the treated cells as determined by clonogenic survival assay and a decreased repair of DSBs as quantified by γ-H2AX foci formation. [24] The authors concluded that this presumed facilitation of DNA repair by EGFR in irradiated cells may explain why EGFR overexpression in tumors is associated with radioresistance.

In other studies on the possible relationship between EGFR and DNA-PK, Das et al. [25] reported that NSCLC cell lines bearing the specific mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain of EGFR that confer dramatic sensitivity to the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors, gefitinib and erlotinib, are considerably more radiosensitive than are wild-type EGFR cells on the basis of clonogenic survival assays. Moreover, these mutant cells demonstrated a delayed resolution of γ-H2AX foci compared to controls suggesting that some aspect of the tyrosine kinase domain of EGFR directly or indirectly governs DNA repair capability and, correspondingly, cell sensitivity to radiation. In a subsequent paper from this same group [26], they show that these mutant forms of EGFR fail to translocate to the nucleus and bind to DNA-PKcs following irradiation confirming the importance of the EGFR-DNA-PKcs interaction in radioresponse and underscoring the efficacy of targeting the EGFR signaling pathway to improve tumor treatment with radiation.

Whether small molecule inhibitors of the tyrosine kinase activity of EGFR also radiosensitize by altering the intracellular distribution of DNA-PKcs is less clear. As mentioned above, Brandyopadhyay et al. [23] were unable to show an interaction between EGFR and DNA-PKcs similar to what was seen with C225 using a potent inhibitor of EGFR’s tyrosine kinase activity, tyrphostin A9. However, Friedmann et al. [15], using a relatively high concentration of gefitinib, 10 μM, was able to demonstrate an association between EGFR and DNA-PKcs and a lowering of DNA-PKcs levels in the nucleus of a human breast cancer cell line. Shintani et al. [17] showed, in irradiated HNSCC cell lines, that a concentration of 1 μM gefitinib lowered the nuclear levels of DNA-PKcs, KU70, and KU80 and this effect correlated with an enhancement of tumor regression in a xenograft model using this combination. In our own studies [27], we were unable to demonstrate that a 1 μM concentration of gefitinib lowered nuclear DNA-PKcs levels in NSCLC cells. Thus, there may be some cell-type or agent-concentration dependency on whether inhibitors of EGFR’s tyrosine kinase activity reduce DNA-PKcs nuclear localization following irradiation. However, small molecule inhibitors may affect the intracellular distribution of other DNA repair proteins. Li et al. [28] have recently reported that erlotinib sequesters BRCA1 in the cytoplasm of irradiated breast cancer cells consistent with a suppression of HRR detected as an attenuation of Rad51 foci and an inhibition of repair of DSBs detected as a prolongation of γ-H2AX foci.

Radiation-induced activation of EGFR affects the transcription of DNA repair genes via downstream signaling

Several important studies have reported that PI3K/AKT and Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK mediated signaling downstream of EGFR may govern radiosensitivity by affecting the transcription of genes that code for proteins involved in DNA repair. For example, Yacoub et al. [29] reported that MEK activity is enhanced and expression of the DNA repair protein, XRCC1, is induced by doses of 2 Gy of ionizing radiation within 30 min. Both of these effects were suppressed by PD98059, a potent MEK inhibitor, correlating with a radiosensitizing effect of PD98059 on prostate cancer cells and suggesting that signaling via the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway influences radiosensitivity by regulating the expression of critical DNA repair proteins. XRCC1 plays an important role in BER specifically participating in the rejoining of SSBs [30]. SSBs, which are normally non-lethal lesions, can be converted to lethal DSBs if their rejoining is compromised. In a second paper from this same group [31], Yacob et al. demonstrated that stimulation of the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway by radiation was at least partially dependent on EGFR because the EGFR inhibitor tyrphostin (AG1478) and PD98059 both attenuated the induction of XRCC1 by radiation. In a further analysis of these relationships, Toulany et al. [32], using a variety of small molecule inhibitors, showed that XRCC1 expression induced by radiation is independent of PI3K/AKT but dependent on the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway whereas basal levels of XRCC1 are governed by PI3K/AKT signaling downstream of EGFR, i.e. inhibitors of EGFR and AKT both resulted in lower levels of basal XRCC1. In addition, this group [32] showed that XRCC1 and DNA-PKcs are physically associated in irradiated cells and that knocking down XRCC1 expression using siRNA enhances residual DSBs as detected on the basis of γ-H2AX foci suggesting that XRCC1 either participates directly in DSB repair or normally repairs SSBs thereby preventing their conversion to DSBs. The transcription of DNA repair genes involved in HRR may also be affected by inhibition of EGFR signaling. Chinnaiyan et al. [19] reported that erlotinib suppresses Rad51 expression following irradiation. More recently, Ko et al. [33] showed that treatment of NSCLC cells with gefitinib resulted in decreased levels of phospho-ERK1/2 and Rad51 protein and message. They also reported that the potent MEK inhibitor, U0126, mimicked the effects of gefitinib suggesting that MEK/ERK signaling downstream of EGFR regulates HRR through controlling the levels of Rad51.

EGFR controls the radiation-induced activation of DNA repair proteins

Finally, EGFR signaling has been shown to affect the phosphorylation status of certain DNA repair proteins, e.g. DNA-PKcs, ATM and H2AX, that require phosphorylation at specific residues for activation following irradiation. In the first of these reports, Toulany et al. [18] show that the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor, BIBX1382BS (BIBX), the PI3K inhibitor, LY294002, and an AKT inhibitor, API-59CJ-OH (API), all suppressed radiation-induced phosphorylation of DNA-PKcs at T2609, a site known to be important for activating DSB repair. This suppressed phosphorylation was detected in K-Ras mutant cells but not in K-Ras wild-type cells. These effects on DNA-PKcs correlated with BIBX-induced radiosensitization based on clonogenic survival assays and an enhanced accumulation of residual γ-H2AX foci in the BIBX-treated cells. The authors concluded that targeting EGFR signaling via the PI3K/AKT pathway in K-RAS mutated cells radiosensitizes such cells by suppressing the radiation-induced activation, specifically phosphorylation of T2609, of DNA-PKcs thereby decreasing repair of DSBs. In a follow-up paper [34], this same group demonstrated that specific inhibition of AKT using API or siRNA knockdown of AKT strongly inhibited radiation-induced phosphorylation of DNA-PKcs at T2609 and S2056. Again, this correlated with radiosensitization of the cells treated under these conditions and a suppression of DSB repair measured by γ-H2AX foci. They also discovered a physical interaction between AKT and DNA-PKcs following irradiation. Based on these data, the authors concluded that DSB repair in irradiated cells is dependent on AKT activity and, therefore, AKT may represent an excellent target to overcome radioresistance of tumor cells.

Another group has performed similar investigations and revealed additional radiosensitizing mechanisms involving signaling downstream of the EGFR. In a report by Golding et al. [35], the influence of the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathway on HRR was examined. When ERK signaling was stimulated by oncogenic Raf-1 expression, a 2-fold increase in HRR was observed. Moreover, a specific inhibitor of ATM, KU-55933, partly blocked radiation-induced ERK phosphorylation suggesting that ATM regulates ERK signaling. Inhibition of ERK signaling using a MEK inhibitor resulted in reduced levels of phosphorylated (S1981) ATM foci and reduced levels of phosphorylated ATM. The conclusions from this study were that signaling through the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway is associated with ATM regulation and HRR and that blockade of ERK signaling has a major effect on radiation-induced phosphor-(S1981) ATM foci formation. In addition, since they also showed that inhibiting ATM kinase with KU-55933 reduced ERK phosphorylation, ATM must control ERK signaling as well. Thus, ATM and ERK signaling could be interacting in a regulatory feedback loop. In a second paper [36], this same group expanded this investigation to include an examination of the influence of AKT and ERK signaling downstream of EGFR on both HRR and NHEJ. Here, they took advantage of glioma cell lines that either expressed a constitutively active variant of EGFR, EGFRvIII, or a dominant-negative construct, EGFR-CD533. They show based on the changes in the kinetics of γ-H2AX foci that EGFRvIII enhances DSB repair whereas EGFR-CD533 significantly reduces repair of DSBs. When HRR and NHEJ were examined specifically, the EGFRvIII stimulated and EGFR-CD533 compromised HRR and NHEJ respectively. Furthermore, inhibitors of both AKT and ERK blocked NHEJ. Taking all of their results together, their observations support the premise that DSB repair is regulated at several levels by growth factor signaling and that the stimulation of DSB repair by EGFRvIII may explain the radioresistance of gliomas that harbor this mutation.

Signaling downstream of IGF1R and c-Met may also govern DNA repair and radioresponse

Although this review has focused thus far on EGFR, several other growth factor receptors with tyrosine kinase like activity are known to be abnormal in cancer and may potentially play roles similar to EGFR in influencing radioresponse. Two that have been examined to date include the insulin growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R) and the receptor for hepatocyte growth factor, c-Met. Both the PI3K/AKT and Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathways are also downstream of these 2 receptors. [37-39] Using a selective inhibitor of IGF1R tyrosine kinase activity, tyrphostin AG 1024, Wen et al. [40] examined the role of IGF1R in modulating radiosensitivity of human breast cancer cells. They showed that AG 1024 suppressed AKT signaling and sensitized these cells to radiation in clonogenic survival assays. More recently, Allen et al. [41] used a monoclonal antibody (A12) that inhibits IGF1R activation and downstream signaling to radiosensitize NSCLC cells in vitro and in vivo. They also tested its effects on DSB repair and showed that A12 inhibited the resolution of γ-H2AX foci following irradiation. Two additional papers reporting on the role of IGF1R in radioresponse have examined a putative interaction between the IGF1R and ATM. Peretz et al. [42] suggest that ATM may regulate IGF1R expression at the level of transcription and, in the other paper, Macaulay et al. [43], provide evidence to indicate that IGF1R signaling can modulate ATM function. Finally, an interaction between IGF1R and HRR has been uncovered by Trojanek et al. [44] They have shown that activation of IGF1R controls the translocation of Rad51 to sites of damaged DNA through the binding of its signaling molecule, insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1), to Rad51 itself. In the absence of IGR1R activation, IRS-1 binds to Rad51 and sequesters it in the perinuclear compartment resulting in less DNA repair by HRR.

Less has been reported with regard to a similar role for c-Met. Two reports [45, 46] illustrate that downregulation of c-Met expression in human glioma cells using either ribozymes or antisense oligodeoxynucleotides enhanced the response of intracranial xenografts to radiation compared to controls. Thus, although neither of these reports concerning c-Met investigated whether the enhanced radiosensitization involved a suppression of DNA repair, small molecule inhibitors of its tyrosine kinase activity are currently being developed that will allow this question to be addressed in the near future. One such inhibitor, SU11274, that is commercially available, has been used in a recent study reported by Ganapathipillai et al. [47]. They demonstrate that cells that express a Met-mutated variant have constitutive levels of phosphorylated Abl and Rad51. These levels were reduced with SU11274 thereby inhibiting radiation-induced Rad51 nuclear translocation and leading to increased DSBs following irradiation.

Conclusions

As this review of the literature related to receptor signaling and DNA repair has hopefully made clear, emerging data convincingly show that the signaling pathways downstream of growth factor receptors intersect with the DNA repair mechanisms to modulate cellular response to ionizing radiation. A summary of this literature is presented in Table 1. We have limited this discussion to just 3 receptors--EGFR, IGF1R, and c-Met—even though there may be others with similar effects. Our purpose was not to exhaust the literature on this topic but, instead, to provide definitive examples of investigations where specific mechanistic insight into how these diverse processes intersect at the molecular level were revealed. Although the involvement of other pathways has not been ruled out, it appears from this review that 2 pathways in particular, i.e. the PI3K/AKT and Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK, mediate the signals downstream of these growth factors receptors in common. As discussed, there are multiple ways in which receptor signaling may modulate DNA repair activity including the direct physical interaction of receptor molecules with repair proteins, governing the transcription of genes that encode repair proteins and regulation of repair protein activation and function through specific phosphorylation events. These mechanisms are not mutually exclusive and the particular involvement of one or more of them appears to be highly dependent on cell type and, of course, growth factor receptor expression status.

TABLE 1. Summary of investigations demonstrating interactions of RTK signaling and DNA repair for three receptors: EGFR, IGF1R, and c-Met.

| EGFR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modulating Agent | Signaling Pathway | Mechanism of DNA Repair Interaction | Readout | Reference |

| C225 | EGFR | Subcellular distribution of DNA-PKcs and/or interaction of DNA-PKcs/EGFR | γ-H2AX foci Radiosensitivity | 14, 16, 24 |

| Mutant EGFR | EGFR | Subcellular distribution of DNA-PKcs and interaction of DNA-PKcs/EGFR | γ-H2AX foci Radiosensitivity | 25, 26 |

| gefitinib | Subcellular distribution of DNA-PKcs | Radiosensitivity | 17 | |

| erlotinib | Sequestration of BRCA1 | γ-H2AX & micronuclei | 28 | |

| tyrphostin | MEK/ERK | Protein levels of XRCC1 | Radiosensitivity micronuclei | 29, 31 |

| BIBX | MEK/ERK | XRCC1/DNA-PKcs interaction | γ-H2AX foci | 32 |

| erlotinib | Rad51 expression | Radiosensitivity | 19 | |

| gefitinib | MEK/ERK | Rad51 expression | 33 | |

| BIBX | P13K/AKT | Phosphorylation of DNA-PKcs | γ-H2AX foci | 18 |

| MEK/ERK | Phosphorylation of ATM | HRR assay ATM foci | 35 | |

| Mutant EGFR | P13K/AKT | Phosphorylation of DNA-PKcs | γ-H2AX foci | 36 |

| IGF1R | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modulating Agent | Signaling Pathway | Mechanism of DNA Repair Interaction | Readout | Reference |

| Tyrphostin | P13K/AKT | Radiosensitivity | 40 | |

| A12 | γ-H2AX foci | 41 | ||

| Antisense to IGF1R | ATM protein levels | Radiosensitivity | 43 | |

| Mutant IGF1R | IRS-1 | Subcellular distribution Of Rad 51 | γ-H2AX foci | 44 |

It is important to realize that, although repair of radiation-induced DSBs critically governs the intrinsic radiosensitivity of cells as determined from in vitro clonogenic survival curves, the response of tumors to radiotherapy in vivo is determined by factors in addition to DNA repair. Pre-clinical investigations indicate that EGFR inhibitors affect tumor response in vivo by reducing repopulation [48, 49], stimulating reoxygenation [49], and suppressing angiogenesis [14, 50, 51]. Potentially, these mechanisms may play equal or even more important roles in determining tumor response in vivo to the combination of EGFR inhibition and radiation than any influence on DNA repair. Moreover, these non-repair related mechanisms may partly explain observations indicating that the radiosensitizing efficacy of monoclonal antibodies such as cetuximab differ from that produced by TKIs such as gefitinib, erlotinib and BIBX1382BS in specific tumors [52, 53]. Recent reviews of this topic suggest that, although this heterogeneity in effectiveness of these EGFR inhibitors is currently poorly understood, it is probably due to the contrasting mechanisms by which these different classes of EGFR inhibitors alter EGFR signaling [54-56]. Monoclonal antibodies inhibit EGFR by internalization of the receptor leading to its degradation or nuclear translocation whereas TKIs leave the receptor intact and transiently suppress its ability to signal downstream [57].

The revelation of specific molecular mechanisms to explain why and how growth factor antagonists such as cetuximab, gefitinib, and erlotinib exert a radiosensitizing effect provides a sound rationale for combining these agents with radiotherapy. It seems clear that, whereas each of these agents has some modest clinical efficacy when given alone, their ultimate clinical utility could be dictated by their ability to synergize in combination therapies as sensitizers. These investigations also establish an entirely new avenue of laboratory research concerning understanding the regulation of DNA repair that takes place in the nucleus by events that are initiated on the plasma membrane. Until recently, connections between these disparate activities were not even imagined. Now, based on the reports reviewed here, more extensive investigations into the molecular mechanisms responsible for these interactions will have to be undertaken in order to fully understand how DNA repair is regulated in the context of cell growth and survival. In addition, future studies in this theme will certainly reveal even more pathways and elements of cell signaling, including those that are not downstream of RTKs, that can be targeted to enhance tumor response to radiation.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by grant PO1 CA06294 from the National Cancer Institute, the Wiegand Foundation, the Gilbert H. Fletcher Chair (KKA), the Kathryn O’Connor Research Professorship (REM) and the United Energy Resources Professorship in Cancer Research (LM).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2005. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:10–30. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Forastiere A, Koch W, Trotti A, Sidransky D. Head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1890–1900. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra001375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Mendelsohn J. The epidermal growth factor receptor as a target for cancer therapy. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2001;8:3–9. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0080003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Grandis JR, Tweardy DJ. Elevated levels of transforming growth factor alpha and epidermal growth factor receptor messenger RNA are early markers of carcinogenesis in head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 1993;53:3579–3584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Camp ER, Summy J, Bauer TW, Liu W, Gallick GE, Ellis LM. Molecular mechanisms of resistance to therapies targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:397–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ono M, Kuwano M. Molecular mechanisms of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) activation and response to gefitinib and other EGFR-targeting drugs. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:7242–7251. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ang KK, Mason KA, Meyn RE, Milas L. In: Monduzzi, editor. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and its inhibition in radiotherapy; 7th International Meeting on Progress in Radio-Oncology ICRO/PGRO; Salzburg, Austria: Medimond, Inc.. 2002.pp. 557–567. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sartor CI. Mechanisms of disease: Radiosensitization by epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2004;1:80–87. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Carracedo A, Pandolfi PP. The PTEN-PI3K pathway: of feedbacks and cross-talks. Oncogene. 2008;27:5527–5541. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Baselga J, Arteaga CL. Critical update and emerging trends in epidermal growth factor receptor targeting in cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2445–2459. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.11.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2129–2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:567–578. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Harari PM, Huang S. Radiation combined with EGFR signal inhibitors: head and neck cancer focus. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2006;16:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Huang SM, Harari PM. Modulation of radiation response after epidermal growth factor receptor blockade in squamous cell carcinomas: inhibition of damage repair, cell cycle kinetics, and tumor angiogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2166–2174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Friedmann BJ, Caplin M, Savic B, et al. Interaction of the epidermal growth factor receptor and the DNA-dependent protein kinase pathway following gefitinib treatment. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:209–218. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Dittmann K, Mayer C, Fehrenbacher B, et al. Radiation-induced epidermal growth factor receptor nuclear import is linked to activation of DNA-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31182–31189. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506591200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Shintani S, Li C, Mihara M, et al. Enhancement of tumor radioresponse by combined treatment with gefitinib (Iressa, ZD1839), an epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, is accompanied by inhibition of DNA damage repair and cell growth in oral cancer. Int J Cancer. 2003;107:1030–1037. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Toulany M, Kasten-Pisula U, Brammer I, et al. Blockage of epidermal growth factor receptor-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-AKT signaling increases radiosensitivity of K-RAS mutated human tumor cells in vitro by affecting DNA repair. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4119–4126. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Chinnaiyan P, Huang S, Vallabhaneni G, et al. Mechanisms of enhanced radiation response following epidermal growth factor receptor signaling inhibition by erlotinib (Tarceva) Cancer Res. 2005;65:3328–3335. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Helleday T, Lo J, van Gent DC, Engelward BP. DNA double-strand break repair: from mechanistic understanding to cancer treatment. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6:923–935. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].van Gent DC, van der Burg M. Non-homologous end-joining, a sticky affair. Oncogene. 2007;26:7731–7740. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Khanna KK, Jackson SP. DNA double-strand breaks: signaling, repair and the cancer connection. Nat Genet. 2001;27:247–254. doi: 10.1038/85798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Bandyopadhyay D, Mandal M, Adam L, Mendelsohn J, Kumar R. Physical interaction between epidermal growth factor receptor and DNA-dependent protein kinase in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1568–1573. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Dittmann K, Mayer C, Rodemann HP. Inhibition of radiation-induced EGFR nuclear import by C225 (Cetuximab) suppresses DNA-PK activity. Radiother Oncol. 2005;76:157–161. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2005.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Das AK, Sato M, Story MD, et al. Non-small-cell lung cancers with kinase domain mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor are sensitive to ionizing radiation. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9601–9608. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Das AK, Chen BP, Story MD, et al. Somatic mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) abrogate EGFR-mediated radioprotection in non-small cell lung carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5267–5274. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Tanaka T, Munshi A, Brooks C, Liu J, Hobbs ML, Meyn RE. Gefitinib radiosensitizes non-small cell lung cancer cells by suppressing cellular DNA repair capacity. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1266–1273. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Li L, Wang H, Yang ES, Arteaga CL, Xia F. Erlotinib attenuates homologous recombinational repair of chromosomal breaks in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9141–9146. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Yacoub A, Park JS, Qiao L, Dent P, Hagan MP. MAPK dependence of DNA damage repair: ionizing radiation and the induction of expression of the DNA repair genes XRCC1 and ERCC1 in DU145 human prostate carcinoma cells in a MEK1/2 dependent fashion. Int J Radiat Biol. 2001;77:1067–1078. doi: 10.1080/09553000110069317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Brem R, Hall J. XRCC1 is required for DNA single-strand break repair in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:2512–2520. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Yacoub A, McKinstry R, Hinman D, Chung T, Dent P, Hagan MP. Epidermal growth factor and ionizing radiation up-regulate the DNA repair genes XRCC1 and ERCC1 in DU145 and LNCaP prostate carcinoma through MAPK signaling. Radiat Res. 2003;159:439–452. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2003)159[0439:egfair]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Toulany M, Dittmann K, Fehrenbacher B, Schaller M, Baumann M, Rodemann HP. PI3K-Akt signaling regulates basal, but MAP-kinase signaling regulates radiation-induced XRCC1 expression in human tumor cells in vitro. DNA Repair (Amst) 2008;7:1746–1756. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ko JC, Hong JH, Wang LH, et al. Role of repair protein Rad51 in regulating the response to gefitinib in human non-small cell lung cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:3632–3641. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Toulany M, Kehlbach R, Florczak U, et al. Targeting of AKT1 enhances radiation toxicity of human tumor cells by inhibiting DNA-PKcs-dependent DNA double-strand break repair. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:1772–1781. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Golding SE, Rosenberg E, Neill S, Dent P, Povirk LF, Valerie K. Extracellular signal-related kinase positively regulates ataxia telangiectasia mutated, homologous recombination repair, and the DNA damage response. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1046–1053. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Golding SE, Morgan RN, Adams BR, Hawkins AJ, Povirk LF, Valerie K. Pro-survival AKT and ERK signaling from EGFR and mutant EGFRvIII enhances DNA double-strand break repair in human glioma cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009:8. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.8.7927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Shaw RJ, Cantley LC. Ras, PI(3)K and mTOR signalling controls tumour cell growth. Nature. 2006;441:424–430. doi: 10.1038/nature04869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Chitnis MM, Yuen JS, Protheroe AS, Pollak M, Macaulay VM. The type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor pathway. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6364–6370. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Guo A, Villen J, Kornhauser J, et al. Signaling networks assembled by oncogenic EGFR and c-Met. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:692–697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707270105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wen B, Deutsch E, Marangoni E, et al. Tyrphostin AG 1024 modulates radiosensitivity in human breast cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:2017–2021. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Allen GW, Saba C, Armstrong EA, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor signaling blockade combined with radiation. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1155–1162. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Peretz S, Jensen R, Baserga R, Glazer PM. ATM-dependent expression of the insulin-like growth factor-I receptor in a pathway regulating radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:1676–1681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041416598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Macaulay VM, Salisbury AJ, Bohula EA, Playford MP, Smorodinsky NI, Shiloh Y. Downregulation of the type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor in mouse melanoma cells is associated with enhanced radiosensitivity and impaired activation of Atm kinase. Oncogene. 2001;20:4029–4040. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Trojanek J, Ho T, Del Valle L, et al. Role of the insulin-like growth factor I/insulin receptor substrate 1 axis in Rad51 trafficking and DNA repair by homologous recombination. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7510–7524. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7510-7524.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Lal B, Xia S, Abounader R, Laterra J. Targeting the c-Met pathway potentiates glioblastoma responses to gamma-radiation. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4479–4486. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Chu SH, Zhu ZA, Yuan XH, Li ZQ, Jiang PC. In vitro and in vivo potentiating the cytotoxic effect of radiation on human U251 gliomas by the c-Met antisense oligodeoxynucleotides. J Neurooncol. 2006;80:143–149. doi: 10.1007/s11060-006-9174-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Ganapathipillai SS, Medova M, Aebersold DM, et al. Coupling of mutated Met variants to DNA repair via Abl and Rad51. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5769–5777. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Huang SM, Bock JM, Harari PM. Epidermal growth factor receptor blockade with C225 modulates proliferation, apoptosis, and radiosensitivity in squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1935–1940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Krause M, Ostermann G, Petersen C, et al. Decreased repopulation as well as increased reoxygenation contribute to the improvement in local control after targeting of the EGFR by C225 during fractionated irradiation. Radiother Oncol. 2005;76:162–167. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2005.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Milas L, Mason K, Hunter N, et al. In vivo enhancement of tumor radioresponse by C225 antiepidermal growth factor receptor antibody. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:701–708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Milas L, Fang FM, Mason KA, et al. Importance of maintenance therapy in C225-induced enhancement of tumor control by fractionated radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67:568–572. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Baumann M, Krause M. Targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor in radiotherapy: radiobiological mechanisms, preclinical and clinical results. Radiother Oncol. 2004;72:257–266. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Krause M, Schutze C, Petersen C, et al. Different classes of EGFR inhibitors may have different potential to improve local tumour control after fractionated irradiation: a study on C225 in FaDu hSCC. Radiother Oncol. 2005;74:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Baumann M, Krause M, Dikomey E, et al. EGFR-targeted anti-cancer drugs in radiotherapy: preclinical evaluation of mechanisms. Radiother Oncol. 2007;83:238–248. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Rodemann HP, Dittmann K, Toulany M. Radiation-induced EGFR-signaling and control of DNA-damage repair. Int J Radiat Biol. 2007;83:781–791. doi: 10.1080/09553000701769970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Zips D, Krause M, Yaromina A, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors for radiotherapy: biological rationale and preclinical results. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2008;60:1019–1028. doi: 10.1211/jpp.60.8.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Astsaturov I, Cohen RB, Harari PM. EGFR-targeting monoclonal antibodies in head and neck cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2006;6:691–710. doi: 10.2174/156800906779010191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]