Abstract

Purpose

The present prospectively designed 15-year longitudinal research was conducted to study whether locus of control is linked to diagnosis, to major symptoms, to functioning and recovery, and to personality for schizophrenia patients, depressive patients, and patients with other major disorders.

Procedure

The research studied 128 patients from the Chicago Follow-up Study at the acute phase and reassessed them 5 times over a 15-year period. Patients were evaluated on locus of control, global outcome, recovery, premorbid developmental achievements, psychosis, diagnosis, depression, and personality variables.

Results

1.) After the acute phase, schizophrenia patients were not more external than other diagnostic groups. 2.) Internality is associated with increased recovery in schizophrenia (p<.05). 3.) A more external locus of control was related to depression (p=.01). 4.) The relationship between externality and psychosis was significant (p<.05).

Conclusions

In severe psychiatric disorders a more external locus of control is not specific to schizophrenia and after the acute phase is not associated with one particular diagnostic group. A more external locus of control is related to fewer periods of recovery, to both depressed mood and psychosis, and to various aspects of personality (p<.05).

1. Introduction

The present longitudinal research studying patients with severe mental disorders was designed to examine whether one's outlook towards life events (based on the concept of locus of control (LOC)) relates to diagnosis, to depression and psychosis, to functioning and recovery and to personality, focusing on schizophrenia and also looking at depressive disorders and other major diagnostic groups.

An important dimension of personality is the variable called locus of control (LOC). This construct, generated through Rotter's social learning theory, refers to the extent to which an individual perceives events in his or her life as being a consequence of his or her actions, and thus under his or her perceived control. It is assessed in terms of whether one believes that events in peoples' lives result from their own efforts, skills, and internal dispositions (internal control) or stem from external forces such as luck, chance, fate or powerful others (external control) (Rotter, 1966; Rotter, 1990).

The dimensions of an individual's orientation toward the world has been investigated in many different normal populations and in various types of disordered populations including eating disorders (Dalgleish, et al., 2001) and depression. Thus LOC has been found to be related to a wide array of affective mood states and personality variables including depression, coping ability, and perceived competence. Depression is one of the most frequently studied concepts in relation to a more external locus of control. The relation between a more external locus of control and increased depression has been supported by studies examining college students (Twenge, Zhang, & Im, 2004), cancer patients (De Brander, Gerits, & Hellemans, 1997), children (Dunn, Austin, & Huster 1999), caregivers (McNaughton, Patterson, Smith, & Grant, 1995), and other populations. Various factors have been proposed as involved in this relation, with this including depressive affect and other elements of depression such as pessimism, low self-esteem, and hopelessness (Abramson, 1989; Alloy, 1999).

While there has been extensive interest in broadening knowledge about LOC and its relation to depression (Lester, 1999), and to severity and potential improvement in depression (Bann, 2004) less research has been conducted with severely disordered psychiatric patients. It would be of value to determine the extent to which individuals with severe mental disorders feel that events in their lives are a consequence of their own behavior.

There has been some research on LOC and psychosis. This includes research by Bentall and colleagues (Bentall & Kaney, 2005; Melo, Taylor & Bentall, 2006), by Warner (1989), by Hoffman and colleagues (2000, 2002), by our own group (Harrow & Ferrante, 1969) and by others. One might expect an external locus of control in a severe disorder such as schizophrenia, with various factors contributing to this, such as the severity and chronicity of the disorder, the persistence over time of major symptoms for some patients with schizophrenia and the frequent work disability found in most of these patients.

Both consumers and mental health professionals have reported that various personality factors may influence outcome and potential recovery in schizophrenia. Among these, a number of theorists have noted that more external beliefs could reduce the extent of personal efforts towards recovery in schizophrenia and internal approaches could increase the chances of rehabilitation and recovery (Tooth, 2002; Bender, 1995; Warner, 1989; & Hoffman, 2000, 2002). In general, potential periods of recovery for some or many patients with schizophrenia, and factors which may facilitate it, have become a major issue. Thus, recent evidence has shown that while schizophrenia is still a relatively poor outcome disorder, some or many patients with schizophrenia experience periods of recovery, with some showing the potential for long periods of recovery (Harrow, 2005; Liberman, 2002). Needed in the field is more information on factors which play a role in recovery, including the potential for personality factors to exert an influence. Both personality and attitudinal approaches may influence both LOC and recovery (Bender, 1995; Tooth, 2003). Viewed from this perspective LOC orientation could influence long term global outcomes and probabilities for recovery. As a result, study of the relation between an external LOC and subsequent outcome and recovery over a prolonged period in schizophrenia could be of considerable importance.

One study that used psychotic patients (Warner et al., 1989) found that a combination of acceptance of the diagnosis of mental illness and internal locus of control was associated with a better outcome in psychosis. This latter research, however, did not determine whether patients with schizophrenia, or certain subtypes of schizophrenia patients, were any more or less likely to be internal than other types of disordered patient populations. In earlier research using an acute inpatient sample, the current team found some tendency for more externality among the schizophrenia patients, although the differences were only moderate (Harrow & Ferrante, 1969; Hansford, Harrow, Groen, 2004).

In addition, the relation in psychiatric patients between locus of control and various dimensions of personality and other important characteristics of the patients (e.g., premorbid developmental achievements, anxiety, anomie, and self-esteem) was not explored fully, even though there is evidence that some personality dimensions may contribute significantly to patients' locus of control orientations and contribute to subsequent outcomes. While previous research has shown the relation between LOC and other personality dimensions (e.g., DeNeve & Cooper, 1998; Judge et al., 2002), research studying the relations between LOC and personality dimensions in severe mental disorders is scant. Because of this paucity, the current research provides a beginning exploration of these relations in patients with severe mental disorders. It also is of importance to further investigate factors such as psychosis and depression, which may be related to the development and maintenance of either a more external or internal locus of control. A comprehensive investigation of the locus of control construct in psychiatric patients would be of interest to both the personality theorist and the clinician.

Overall, the current research, employing a large sample of patients studied on a longitudinal basis, investigated the following major questions: 1) are patients with schizophrenia more external than other disordered patients?; 2) is internality related to better global functioning and to potential recovery in schizophrenia?; 3) is externality related to depression in severely disordered patients?; 4) is externality related to psychosis?; and 5) is LOC in severely disordered patients related to various personality dimensions and other characteristics of these disordered patients?

2. Method

2.1 Patient Sample

The present research is based on data from the Chicago Followup Study, a prospective multi-follow-up research program investigating schizophrenia and affective disorders longitudinally. One of the goals of the study was to provide longitudinal data on functioning, adjustment, potential recovery, and major symptoms (e.g., psychosis, thought disorder, negative symptoms and depression) in schizophrenia and mood disorders (Harrow, Goldberg, Grossman, & Meltzer, 1990; Carone, Harrow, & Westermeyer, 1991; Harrow, Herbener, Shanklin, et. al., 2004a; Harrow, Jobe, Herbener, et. al. 2004b Harrow, Sands, Silverstein, et. al., 1997; Harrow, Grossman, Herbener, & Davis, 2000; Harrow, O'Connell, Herbner, et al., 2003; Harrow, Grossman, Jobe, et. al. 2005; Harrow & Jobe, In Press).

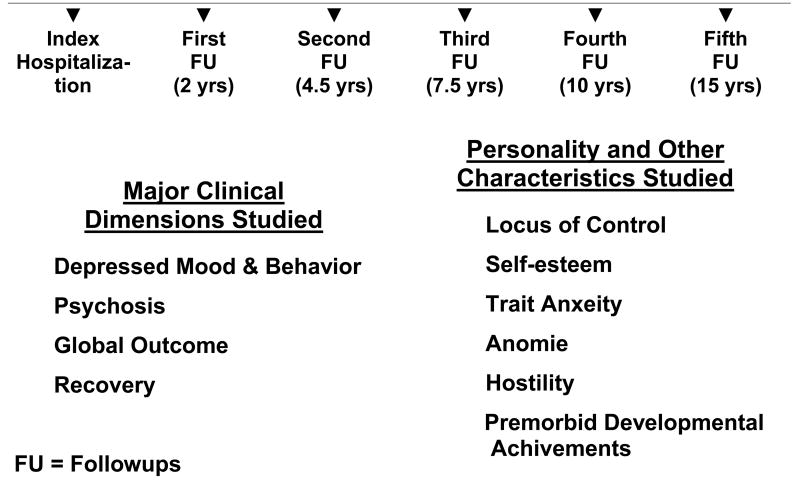

The present sample of 128 patients includes 43 patients with schizophrenia, 41 patients with other types of psychotic disorders, and 44 non-psychotic depressed patients, using RDC criteria (Spitzer, Endicott, & Robins, 1978). The patients were assessed prospectively at index hospitalization and then reassessed for functioning and adjustment in 5 successive follow-up interviews over 15 years. These interviews occurred at 2 years post-hospitalization and then again at 4.5 years, at 7.5 years, at 10 years, and 15 years post-hospitalization. Figure 1 reports the research design, including the schedule of longitudinal assessments and the major variables studied. The patients were assessed for locus of control at the 4.5-year follow-ups. Since measures of functioning, adjustment, and recovery were assessed at each follow-up, this permitted us to assess the relation between a) an internal locus of control at the 4.5-year follow-ups and b) major symptoms, select personality variables, global adjustment, and recovery at the same follow-ups, as well as the potential for recovery at any later follow-ups over the 15-year period.

Figure 1. Phase of Disorder Studied.

The diagnosis for each patient was based on the administration of at least one of two structured research interviews at index hospitalization. These structured interviews have been used successfully in previous studies: 1) the Schizophrenic State Inventory, with each interview tape-recorded (Grinker & Harrow, 1987) and 2) the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS; Endicott & Spitzer, 1978). We assessed inter-rater reliability for a diagnosis of schizophrenia and obtained a kappa of 0.88.

The present research was designed to study patients who, at index hospitalization, were relatively young, non-chronic patients to reduce the effects of long-term treatment; long-term treatment can sometimes be a factor when chronically ill patients with years of previous treatment are studied. The mean age of the patient sample was 23 years at index hospitalization. 52% of the patients was male. 51% of the sample was first-admission patients at index. The mean educational level of this sample was 13.2 years at index. There were no significant diagnostic differences in age, but there were sex differences, with a higher percentage of the schizophrenia patients being male (70%) and a higher percentage of the non-psychotic depressive patients being female (64%). These sex differences are consistent with the typical modern distribution of young patients with schizophrenia and depression (McGrath, 2005). Based on the Hollingshead-Redlich Scale for Socioeconomic Status (SES; Hollingshead & Redlich, 1958) with parental SES as the criterion, 54% of the sample was from households with SES of 1 to 3 (patients from families of higher socioeconomic status), and 46% was from households with SES of 4 or 5 (patients from families of lower socioeconomic status).

2.2 Locus of Control

Locus of control, which is a continuous variable, was measured at the 4.5-year follow-up using a modified version of Rotter's Internal versus External Control of Reinforcement Scale (I.E. Scale) (Rotter, 1966). Rotter's original I.E. Scale consists of 23 forced-choice I.E. items and 6 filler items. The modified I.E. Scale used in this research consisted of 11 I.E. items of the original 23 forced-choice items and 2 filler items. As an example, one of the forced choice items was “people's misfortunes result from the mistakes they make,” vs. “many of the unhappy things in people's lives are partly due to bad luck.” Higher scores indicate a greater degree of externality and lower scores indicate a more internal locus of control on the 11 items. The patient is instructed to select one statement out of each pair that he or she believes to be more accurate (Rotter 1966). The relation between scores on the full I.E. Scale and scores on the modified version used in this research was assessed (r=.81, p<.001). Since LOC is a continuous dimension, most of the analyses in the current paper on LOC are conducted using the full range of scores. However, for convenience in studying the severely disordered patients the sample also was dichotomized into two groups. This included one group that was more internal on the 11-item LOC scale (scores of 14 and less) and one that was more external (scores of 15 and up). This was done by using the mean on the 11-item LOC scale of a group of non-psychotic patients as a boundary line to divide the sample of patients into two groups. Using this score to divide the current sample there were 19 schizophrenia patients who were more internal and 24 who fit into the more external group. There were 24 patients with other types of psychotic disorders who fit into the more internal group and 17 who fit into the more external group. Among the nonpsychotic depressive disorders, 23 fit into the more internal group and 21 into the more external group.

2.3 Follow-up Assessments

Follow-ups were conducted by trained interviewers who were blind to diagnosis and, after the first wave of follow-ups, were blind to the results of previous follow-ups. Informed written consent was obtained at each assessment.

The focus of the current report involves locus of control and its relation to other variables of importance. Scores on locus of control were assessed and scored at the 4.5-year follow-ups.

In addition, at the 4.5-year follow-ups, we also collected and scored a series of attitudinal and personality variables. These included scales to assess trait anxiety (Katz & Lyerly, 1963; Derogatis & Lazarus, 1994), self-esteem (Rosenberg, 1965), hostility (Katz & Lyerly, 1963), and depressed mood and behavior (Katz & Lyerly, 1963). The scale on depressed mood and behavior included items on feeling blue, getting tired easily, blaming oneself, trouble concentrating, loss of appetite, easily moved to tears and diminished interests.

The instruments administer also included a scale to assess anomie (Srole, 1962). One might expect a strong relation between external LOC, which involves a view of events in one's life as being due to external forces and the concept of high anomie, which involves views of a breakdown of norms or social standards, with feelings of alienation and disenfranchisement from society. This is often accompanied by apathy, and by feeling powerless. Premorbid developmental achievements also were assessed prospectively at index hospitalization employing a widely-used scale (Zigler & Glick, 2001; Glick, Zigler, & Zigler, 1985); Westermeyer & Harrow, 1986). This enabled us to assess the relations between locus of control and these variables in the current patient sample.

In addition to providing data on select personality dimensions and other patient characteristics, the study's design also allowed us to examine the relations between a) locus of control, b) global functioning, c) recovery, and d) major symptoms for periods up to 10 years later. Thus, at each follow-up, the patients were given structured interviews to assess functioning (e.g., work, social functioning, potential rehospitalization, treatment, etc.) and the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (Endicott & Spitzer, 1978) to assess major symptoms, such as psychosis and depression. To assess global adjustment at each follow-up, we used the 8-point LKP Scale developed by Levenstein, Klein, and Pollack (1966). This scale has been used successfully by our research team and others (Grinker & Harrow, 1987; Harrow et al., 1997; Harrow et al., 2000; Harrow et al., 2004a). Ratings on this scale, obtained at each follow-up, are based on work and social adjustment, level of self-support, life disruptions, major symptoms, relapse, potential suicide, and rehospitalization.

On the 8-point LKP Scale, ratings for global outcome in the year before follow-up range from 1 (adequate functioning or complete remission during the follow-up year) to 8 (very poor psychosocial functioning, considerable symptoms, and lengthy rehospitalization).

2.4 Operational Definition of Recovery

The operational criteria for a period of recovery requires 1) the absence of major symptoms throughout the year (absence of psychosis and absence of negative symptoms), 2) no rehospitalization during the follow-up year, and 3) adequate psychosocial functioning. This latter feature required instrumental work half time or more (a score of “2” or more on the Strauss-Carpenter Scale for Work Functioning). It also required acceptable social functioning during the follow-up year (a score of “2” or more on the Strauss-Carpenter Scale for Social Functioning) (Strauss & Carpenter, 1972). This scale for recovery has been used successfully in previous research (Harrow et al., 2005; 2007; Grossman, Harrow, Rosen, & Faull, 2006). Recovery at any given follow-up does not automatically prejudge whether recovery will continue during future years, which, for patients with schizophrenia, may be a function of a) the natural course of schizophrenia, b) individual characteristics of the patient assessed which may involve locus of control and many other variables, and c) treatment. The index of recovery used provides data on (a) the percentage of patients in recovery at any follow-up year, and (b) the cumulative percentage of patients who, over the 15 years of follow-up, ever show an interval or period of recovery.

2.5 Medications

As is typical in the natural course of schizophrenia and other major disorders over many years, no single uniform treatment plan emerged for all patients in this naturalistic multi-year study. At the 4.5-year follow-up, when locus of control was studied, 70% of the patients with schizophrenia were receiving medications of some type with 61% of them on antipsychotics. At the 4.5-year follow-ups 51% of the other types of psychotic disorders were on medications, with 30% of them on antipsychotics. 26% of the non-psychotic depressive patients were on medications. Patients with schizophrenia who were on antipsychotic medications at the 4.5-year follow-up showed slightly more external LOC scores then those who were not on any medications, but the differences at the 4.5-year follow-ups were not statistically significant (t = 1.02, df = 37, n.s.). Previous analyses had indicated that schizophrenia patients with more internal LOC were significantly more likely than more external schizophrenia patients to go off antipsychotic medications many years later (Harrow & Jobe, 2007).

2.6 Data Analyses

The data analyses included comparisons of the different diagnostic groups using one-way ANOVA's (f tests) and contrast tests when more than two groups were compared in the analyses, and using 2×2 ANOVAs when several different dimensions were analyzed simultaneously. Individual groups were compared using t tests for differences between independent groups (e.g. differences in scores on depressed mood and behavior for the more internal vs. the more external LOC groups). The effect size is reported for t-tests with p < .10. The effect size is also reported for ANOVAs where the F test was p < .10, using partial eta squared. Two by 2 comparisons of dichotomized variables were assessed by chi square. This included comparisons of patients who were ever in recovery versus those who were never in recovery during the 15 year period.

Pearson product moment correlations were computed to assess the relation between locus of control and other major variables, including global outcome. Among other analyses, this included study of the relation between LOC and various dimensions of personality, premorbid developmental achievements, and concurrent depressed mood and behavior.

In this paper, the probabilities reported for all statistical tests are 2-tailed.

3. Results

3.1 Relation Between Externality and Diagnosis

Table 1 presents data on diagnosis for the three main patient populations, schizophrenia patients, non-psychotic depressed patients, and other types of psychotic disorders. Diagnosis was not closely related to externality on locus of control. The means indicated that at the 4.5 year follow-ups schizophrenia patients were not more external than other disordered groups, such as patients who, earlier, at the acute phase, had a non-psychotic depressive disorder. The means for the schizophrenia patients, who were functioning more poorly than the other two groups, were slightly more external than the other groups, but the differences were not significant (F = .38, df = 2,125, n.s.). Similarly, a separate analysis within the sample of patients with schizophrenia of paranoid versus undifferentiated schizophrenia patients did not show a significant difference in LOC between these two subtypes of schizophrenia (t = .28, 40 df, p > .40). At the 4.5-year follow-ups, bipolar patients did not differ significantly from other psychotic and non-psychotic patients on locus of control (t = .69, 126 df, p > .40).

TABLE 1. Locus of Control at 4.5 Year Followups: Diagnostic Comparisons.

| Locus of Control | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean* | SD | N | |

| Schizophrenia Patients | 15.14 | 2.21 | 43 |

| Other Types of Psychotic Patients | 14.73 | 3.07 | 41 |

| Nonpsychotic Depressed Patients | 14.66 | 2.90 | 44 |

Higher scores represent a more external LOC

F=.38, df= 2,125, p>.40

3.2 Relation Between Externality and Global Outcome

The results on the relation between locus of control and global outcome for the overall sample was significant in the direction of more external patients having poorer global outcomes (r=.23, 126 df, p<..01). The similar correlation for the smaller sample of patients with schizophrenia was positive, but not significant (r=.26, 41 df, .05<p<.10).

3.3 Do Schizophrenia Patients with a More Internal Locus of Control Have Increased Chances of Having a Subsequent Period of Recovery?

Recovery was studied using the index involving cumulative data from all 5 followups, focusing on the patients who were ever in a period of recovery and those never experiencing a period of recovery at any follow-up during the 15-year period. (The category of “recovery,” lasting at least a year, is defined operationally in the Method section.) At least one or more periods of recovery over the 15-year period were experienced by a number of patients from each diagnostic group, including the group of schizophrenia patients. This included 47% of the RDC diagnosed schizophrenia patients, 68% of the other types of psychotic patients, and 77% of the nonpsychotic depressed patients.

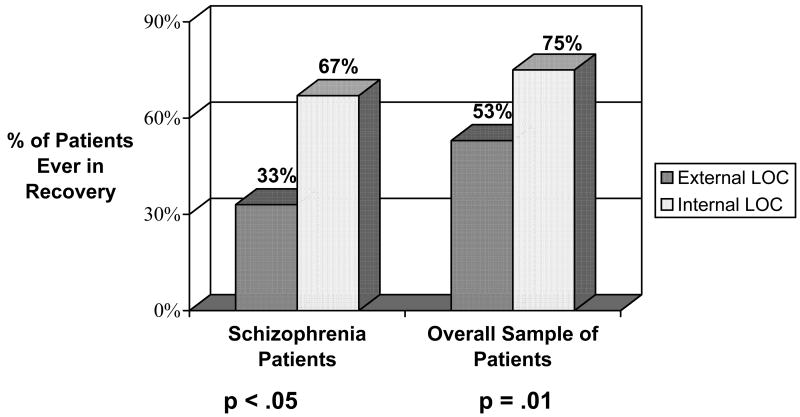

Figure 2, using the 15-year cumulative data, reports the percent of patients in recovery from the more internal groups of patient and from the more external groups. Patients with schizophrenia who have a more internal locus of control were more likely than schizophrenia patients with a more external locus of control to experience one or more subsequent periods of recovery over the 15 years (χ2= 4.58, 1 df, p<05). The results were similar for the overall sample of patients (χ2= 6.50, 1 df, p=01).

FIGURE 2. Patients Ever in Recovery Over 15-year Period.

3.4 The Relation Between External Locus of Control and Depression

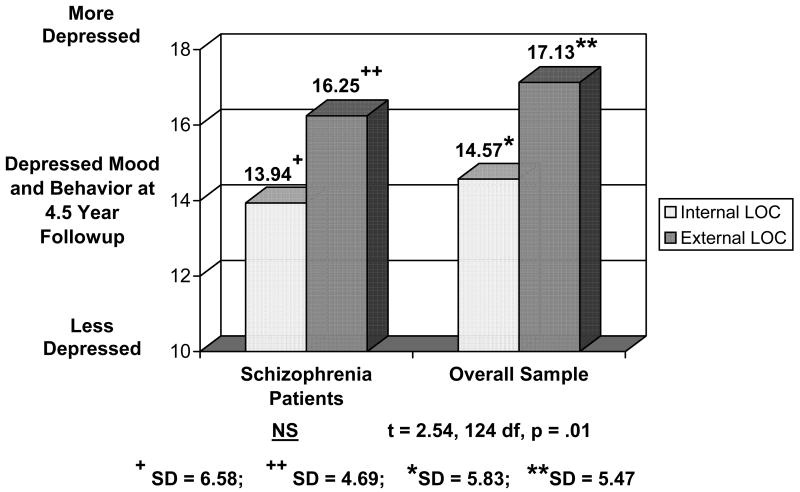

Figure 3 presents the means at the 4.5-year follow-up for depressed mood and behavior for the schizophrenia patients and the overall sample, with each group divided on whether not the patients had a more internal or more external locus of control. The relation between LOC and depression was significant for the overall sample (t = 2.54, 124 df, p = .01) indicating that patients who were more external at the 4.5-year followups were likely, concurrently, to be more depressed, while those patients who were more internal on LOC were likely, concurrently, to be less depressed at the 4.5 year followup. The effect size for this comparison is 0.45.

FIGURE 3. Relationship Between Locus of Control and Depression.

3.5 The Relation Between External Locus of Control and Psychosis

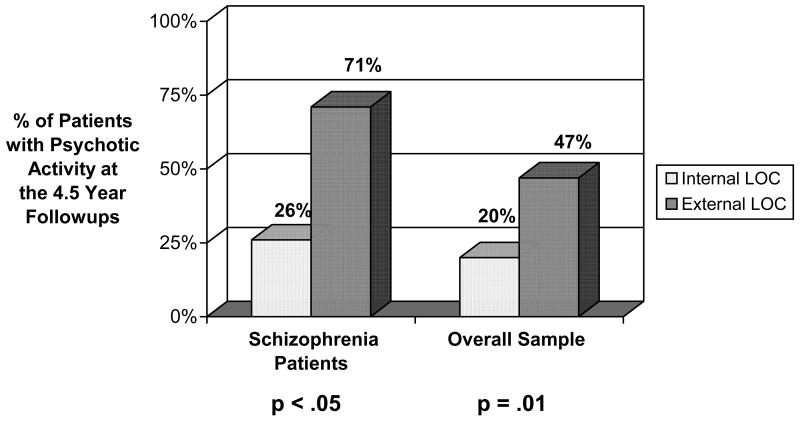

Figure 4 presents the data on locus of control and psychotic activity for the overall sample and for the schizophrenia patients, reporting the percent of internal and external patients with psychotic activity. A 2X2 ANOVA was calculated on the LOC scores of the overall sample with the 2 main effects being diagnoses (schizophrenia vs. the other diagnostic groups) and psychosis (psychotic vs. non-psychotic) at the 4.5 year followups. The main effect for diagnosis was not significant (F=.00, df=1,122, p>.40). The main effect for psychosis was significant (F=8.84, df=1,122, p<.01). The effect size, using partial Eta squared was .068. The interaction effect was not significant (F=.05, df=1,122, p>.40).

FIGURE 4. Relationship Between Psychosis and Locus of Control.

In a separate analysis for the schizophrenia patients, an additional 2X2 ANOVA was conducted on the LOC scores for this diagnostic group, and for the subtypes of schizophrenia. The 2 main effects were psychosis at the 4.5 year followups and subtypes of schizophrenia (paranoid schizophrenia vs. undifferentiated schizophrenia). The main effect for psychosis was significant (F=.4.85, df=1,38, p<.05). The effect size, using partial eta squared, was .113. The main effect for diagnostic subtype was not significant (F=.14, df=1,38, p>.40). The interaction effect was not significant (F=.06, df=1,38, p>.40). In this analysis, the interaction effect provides information on whether psychotic patients from one subtype of schizophrenia (i.e., paranoid schizophrenia) are more internal or external on LOC than psychotic patients from the other major subtype of schizophrenia studied (i.e., undifferentiated schizophrenia).

3.6 Relation Between Locus of Control and Personality Dimensions and Other Patient Characteristics

Table 2 presents the data on the relation between locus of control and several dimensions of personality. For the patient sample the data indicate a significant relation between locus of control and several different dimensions of personality. In particular, patients who were external were significantly more likely to be patients high on trait anxiety (r = .25, 125 df, p < .01) to be hostile (r = .19, 125 df, p<.05), to be higher on anomie (r = .44, 122 df, p<.001), and to have lower self-esteem (r = .29, 123 df, p<.01).

TABLE 2. Relationship Between Locus of Control and Characteristics of the Patient Sample*.

| r | N | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | .25 | 127 | < .01 |

| Self-esteem | .29 | 125 | < .01 |

| Hostility | .19 | 127 | < .05 |

| Anomie | .44 | 124 | <.001 |

| Premorbid Developmental Achievements | .03 | 126 | NS |

Positive correlations reflect the relation between external LOC and poor or pathological scores on the dimensions listed

4. Discussion

4.1 Locus of Control and a Diagnosis of Schizophrenia

Are patients with schizophrenia significantly more external? The issue of whether a diagnosis of schizophrenia is significantly related to locus of control, specifically an external locus of control, has been approached by comparing schizophrenia patients against other diagnostic groups, including non-psychotic depressive patients and other psychotic patients. The question of locus of control being related to diagnosis has been explored within different subtypes of schizophrenia (Cash & Stack, 1973; Pryer & Steinke, 1973), such as patients with paranoid schizophrenia versus patients with undifferentiated schizophrenia, but there is little current information on how locus of control is related to broader diagnostic classifications. The current data suggest that an external locus of control is not specific to schizophrenia and is not associated with one particular major diagnostic group. These results are somewhat surprising since an external locus of control (Warner et al., 1989; Bender 1995) is thought to be significantly related to poorer global outcomes. While the current results indicate that at the 4.5 year followups bipolar patients do not differ significantly from other patients on LOC, other evidence suggest that when studied at the accute phase, during an acute manic episode, bipolar patients tend to be more internal than other types of disordered patients (Harrow & Ferrante, 1969). The differences in the relationships shown by the current bipolar patients (who did not have major manic symptoms at the 2-year assessments) and the relationships for a different sample at a different phase of disorder (at the acute phase when they were showing acute manic symptoms) supports other evidence indicating that LOC may shift, depending on differences in the symptomatic picture.

The current data also indicate that locus of control is more closely related to various dimensions of personality than to the diagnosis of schizophrenia. Thus, the data showed that an external locus of control was significantly related to a number of dimensions of psychopathology and personality including anxiety, hostility, anomie, poor self-esteem, and fewer subsequent periods of recovery. In an effort to predict the effectiveness of treatment and when forecasting on the possibility of partial or complete recovery, various personality characteristics and dimensions of functioning may be important influences. Recent research of ours has indicated that patients with schizophrenia who are more anxiety-prone are more likely to show poorer global outcome, fewer periods of recovery, and more recurring psychosis (Harrow & Jobe, In Press; Shirk, 2005).

4.2 Locus of Control and Global Outcome

The data provide both positive and mixed results on the relation between externality and poor global functioning. For the overall sample the relation was significant (p<.01). For the smaller-in-size sample of schizophrenia patients the relation was also positive, but not significant (r = .26, 41 df, .05 < p < .10).

Much of the current research on locus of control and global outcome is positive (Bender, 1995; Warner et al., 1989; Hoffman, Kupper, & Kunz, 2000), but there are contradictory results (Telesh, 2003). The Warner study is particularly relevant to the current research since the patient population (schizophrenia patients, bipolar patients, etc.) is similar in composition to the sample in this study. Overall, while the relation between locus of control and global outcome in this sample was positive, it was only a modest relation. Although the assessment of the 128 patients from different diagnostic groups six times over the 15-year period is very rare in the field, even more frequent assessments of global outcome over shorter time periods during this 15 – year period would be preferable, and this represents a limitation of the study. Further, more definitive research in this area is needed.

4.3 Recovery and Locus of Control

Data relating locus of control to important dimensions of outcome in patients with schizophrenia many years later, such as the potential for later periods of recovery, had not previously been available to the field.

Potential recovery in schizophrenia and possible factors related to it have become an increasingly important issue for professionals and for mental health consumers (Liberman, 2002; Liberman, Kopelowicz, Ventura, & Gutkind, 2002; Harrow et al., 2005; Tooth, Kalayanasundaram, Glover, & Momenzadah, 2003). The data on locus of control and recovery for the patients indicate that those who have an internal locus of control were more likely to experience a period of recovery at some point over the 15-year period. A number of patients with schizophrenia never or rarely experienced complete recovery. The current data on intervals of recovery support the hypothesis that an internal locus of control may be a valuable personality variable that may contribute to patients with schizophrenia achieving periods of recovery.

We would propose that internality and recovery may exert reciprocal positive influences on each other. Some patients who initially fail at a challenging task may become discouraged and adopt the belief that recovery and good mental health are beyond their abilities and control, leading these patients to put forth even less effort the next time they are faced with a similar situation, resulting in even less likelihood of recovery. If this negative approach or outlook goes untreated, this self-perpetuating trend can become a downward cycle of more subsequent psychopathology, leading to an increasingly more external locus of control. This could have a strong negative effect on patients and create states similar to learned helplessness.

The data which could suggest a possible reciprocal effect concerning the relation between recovery and increased internality on the continuum of LOC would fit within the findings of Strauss and Carpenter (Strauss & Carpenter, 1972; Carpenter & Strauss, 1991). They suggest an open- linked system between different aspects associated with outcome in severe mental disorders, with different factors (and possibly LOC) influencing each other to a degree, but no one factor totally determining outcome, and in this case not totally determining recovery.

Obviously, periods of recovery in schizophrenia are usually dependent on multiple factors. These include the type of treatment, internal constitutional factors of the particular patient, and the external environment of the patient (Falloon, et. al. 1985). Mental health consumers who have reported about their experiences of recovery have noted that their attitudes and approaches have been of help in their positive outcomes (Tooth, et. al, 2003). The current data support this outlook and suggest that some personality and attitudinal factors, such as a more internal locus of control, may be contributing factors. These findings support previous research in which schizophrenia patients who experienced good rehabilitation outcomes had significantly more internal scores on locus of control (Hoffman & Kupper, 2002).

4.4 Locus of Control and Depression

For the overall sample, an external locus of control was related concurrently to depressed mood and behavior. Externality may be an influential factor in this type of mood state. The data tend to support much of the research done on locus of control and depression, which generally indicates that externality is linked to depression (Daniels & Guppy, 1997). The data indicating that externality is significantly related to concurrent depression for the psychiatric population fit a general model in which the relation between externality and depression exists for multiple patient populations. When assessing the relation between depression and externality, it is difficult to say which trait appears first in a patient. Similar to internality and potential recovery, externality and depression seem to affect each other in a reciprocal fashion. Indeed, theorists have proposed that LOC may shift with changes in various personality dimensions. The current data in Table 2 on the relation of LOC to various personality factors do show a number of personality dimensions which are related to LOC. Among those personality factors low self-esteem and high anomie are two of the prominent ones related to a more external LOC.

In relation to depression, many depressed patients believe that they are bound to fail regardless of the effort put forth, so they do little to improve their condition instead of striving for success. This, in turn, can foster an increasingly polarized external orientation. On the other hand, perhaps external patients, believing that they are hopelessly unable to influence their own outcomes, are more likely to become depressed with their perceived lack of control over their own fates as one contributing factor. Alloy, Abramson and colleagues (1989, 1999) with both retrospective and prospective tests examined this issue. The authors studied high risk versus low risk participants based on most negative responses versus most positive responses of these non-depressed participants in the “Temple-Wisconsin Cognitive Vulnerability to Depression” project. They found that the high risk group (due to cognitive vulnerability) showed twice the rate of lifetime depression than the low risk group. An additional factor to consider is that symptoms such as depression usually diminish over time, and LOC may also shift with the reduction in depression.

4.5 Locus of Control and Psychosis

Bentall and colleagues, studying LOC and other important dimensions in different types of paranoid patients (Melo, et al, 2006) have emphasized the instability of paranoid symptoms, a finding also confirmed by Appelbaum (2004) and by our group (Harrow & Jobe, In Press). Bentall and Kaney (2005) also have emphasized that LOC and other similar characteristics are not stable traits among schizophrenia patients. Rather, they vary with symptoms and life events (Melo, et al., 2006), with negative events increasing externality in both patients with paranoid schizophrenia, and with depression, with this often leading to a more pessimistic attributional style.

In the current overall sample, patients who were psychotic at the time of assessment for locus of control and other personality dimensions were significantly more likely to be external than non-psychotic patients. Similarly, patients with schizophrenia who were psychotic at the time of assessment were also significantly more likely to be external. There have been hypotheses in the field about differences in externality or locus of control between schizophrenia patients with and without specific types of psychotic symptoms (Cash & Stack, 1973). Our data indicate that the current results are not due to one subtype of schizophrenia. Thus patients with paranoid schizophrenia were not more external than non-paranoid schizophrenia patients. The nonsignificant interaction for the 2×2 ANOVA assessing LOC for schizophrenia subtypes and for psychotic vs. nonpsychotic schizophrenia patients indicate similar relations with LOC for a) paranoid schizophrenia patients who were psychotic as compared to b) patients from the undifferentiated schizophrenia subgroup who were psychotic. The finding that externality is significantly related to psychosis supports some of the limited amount of research available in the field (Archer, 1980; Levine, Jonas, & Serper, 2004). However, the data failed to support the notion proposed by other researchers (Cash & Stack, 1973) that certain subtypes of schizophrenia patients, such as paranoid schizophrenia patients, are more likely to be external than other subtypes, such as non-paranoid schizophrenia patients. There is not good evidence available concerning why patients who are psychotic are more external than patients who are not psychotic and whether their externality is a factor involved in their being psychotic. Future research should attempt to further clarify empirically why psychotic patients are more external.

Acknowledgments

Supported, in part, by USPHS Grants MH-26341 and MH-068688 from the National Institute of Mental Health, USA (Dr. Harrow).

The authors are indebted to Robert Faull for his assistance with data preparation and statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Martin Harrow, Professor, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois College of Medicine, 1601 W. Taylor (M/C 912), Chicago, IL 60612.

Barry G. Hansford, Georgetown University Medical Center, 4435 Greenwich Parkway, Washington, DC 20007

Ellen B. Astrachan-Fletcher, Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois College of Medicine, 912 S. Wood St. (M/C 913), Chicago, IL 60612

References

- Abramson LY, Metalsky GI, Alloy LB. Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review. 1989;96:358–372. [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Whitehouse WG, Hogan ME, Tashman NA, Steinberg DL, Rose DT, Donovan P. Depressogenic cognitive styles: Predictive validity, information processing and personality characteristics, and developmental origins. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1999;37:503–531. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum P, Robbins P, Vesselinov R. Persistence and stability of delusions over time. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2004;45:317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer R. Generalized expectancies of control, trait anxiety, and psychopathology among psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1980;48:736–742. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.48.6.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bann C, Parker C, Bradwejn J, Davidson J, Vitiello B, Gadde K. Assessing patient beliefs in a clinical trial of hypericum perforatum in major depression. Depression and Anxiety. 2004;20:114–122. doi: 10.1002/da.20036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender A. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: the Sciences and Engineering. Vol. 56. 1995. The relationship between health locus of control, perceived self-efficacy, hardiness, and recovery in schizophrenia; p. 2553. [Google Scholar]

- Bentall R, Kaney S. Attributional lability in depression and paranoia. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;44:475–488. doi: 10.1348/014466505X29602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carone J, Harrow M, Westermeyer J. Posthospital course and outcome in schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;48:247–253. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810270059008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter W, Strauss J. The prediction of outcome in schizophrenia IV: Eleven-year follow-up of the Washington IPSS cohort. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1991;179:517–525. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199109000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash T, Stack J. Locus of contral among schizophrenics and other hospitalized psychiatric patients. Genetic Psychology Monographs. 1973;87:105–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgleish T, Tchanturia K, Serpell L, Hems S, de Silva P, Treasure J. Perceived control over events in the world in patients with eating disorders: A preliminary study. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;31:453–460. [Google Scholar]

- DeNeve KM, Cooper H. The happy personality: A meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin. 1998;127:197–229. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.124.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels K, Guppy A. Stressors, locus of control, and social support as consequences of affective psychological well-being. Journal of Occupational Heath Psychology. 1997;2:156–174. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.2.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Brander B, Gerits P, Hellemans J. Self-reported locus of control is based on feelings of depression as well as on asymmetry in activation of cerebral hemispheres. Psychological Reports. 1997;80:1227–1232. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1997.80.3c.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis L, Lazarus L. Scl-90-r, brief symptom inventory, and matching clinical rating scales. In: Maruish M, editor. The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcome assessment. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn D, Austin J, Huster G. Symptoms of depression in adolescents with epilepsy. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:1132–1138. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199909000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Spitzer R. A diagnostic interview. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1978;35:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770310043002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falloon I, Boyd J, McGill C, Williamson M, Razani J, Moss H, et al. Family management in the prevention of morbidity of schizophrenia. Clinical outcome of a two-year longitudinal study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1985;42(9):887–896. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790320059008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick M, Zigler E, Zigler B. Developmental correlates of age at first hospitalization in nonschizophrenic psychiatric patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1985;173:677–684. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198511000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinker R, Harrow M, editors. Clinical research in schizophrenia: A multidimensional approach. Springfield IL: Thomas CC; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman L, Harrow M, Rosen C, Faull R. Sex differences in outcome and recovery for schizophrenia and other psychotic and nonpsychotic disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57:1–7. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.6.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansford B, Harrow M, Groen E, Kaplan K, Faull R. Is external locus of control related to schizophrenia, global outcome, and major psychopathology?. Scientific Proceedings of the 2004th Annual Meeting of the Midwestern Psychological Association; 2004. p. 83. [Google Scholar]

- Harrow M, Ferrante A. Locus of control in psychiatric patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1969;33:582–589. doi: 10.1037/h0028292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrow M, Goldberg J, Grossman L, Meltzer H. Outcome in manic disorders: A naturalistic followup study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1990;47:665–671. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810190065009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrow M, Grossman L, Herbener E, Davis E. Ten-year outcome: Patients with schizoaffective disorders, schizophrenia, affective disorders, and mood-incongruent psychotic symptoms. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;177:421–426. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.5.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrow M, Grossman L, Jobe T, Herbener E. Do patients with schizophrenia ever show periods of recovery? A 15-year multi-followup study. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2005;31:723–734. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrow M, Herbener E, Shanklin A, Jobe T, Rattenbury F, Kaplan K. Followup of psychotic outpatients: dimensions of delusions and work functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2004a;30(1):147–161. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrow M, Jobe T. Factors Involved in Outcome and Recovery in Schizophrenia Patients Not on Antipsychotic Medications: A 15-Year Multi-Followup Study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2007;195:406–414. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000253783.32338.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrow M, Jobe T. Prognosis of Persecutory Delusions: A 20-Year Longitudinal Study. In: Freeman D, Garety P, Bentall R, editors. Persecutory Delusions: Assessment, Theory and Treatment. Oxford: Oxford University Press; In Press (b) [Google Scholar]

- Harrow M, Jobe T, Herbener E, Goldberg J, Kaplan K. Thought disorder in schizophrenia: Working memory and impaired context. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2004b;192:3–11. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000105994.78952.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrow M, O'Connell E, Herbener ES, Altman AM, Kaplan KJ, Jobe TH. Disordered verbalizations in schizophrenia: A speech disturbance or thought disorder? Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2003;44:353–359. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(03)00113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrow M, Sands J, Silverstein M, Goldberg J. Course and outcome for schizophrenia vs other psychotic patients: A longitudinal study. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1997;23:287–303. doi: 10.1093/schbul/23.2.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman H, Kupper Z. Facilitators of psychosocial recovery from schizophrenia. International Review of Psychiatry. 2002;14:293–302. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman H, Kupper Z, Kunz B. Hopelessness and its impact on rehabilitation outcome in schizophrenia-an exploratory study. Schizophrenia Research. 2000;43:147–158. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00148-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead A, Redlich F. Social class and mental illness. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judge TA, Erez A, Bono JE, Thoresen CJ. Are measures of self-esteem, neuroticism, locus of control, and generalized self-efficacy indicators of a common core construct? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83:693–710. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.3.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz M, Lyerly S. Methods for measuring adjustment and social behavior in the community: I. Rationale, description, discriminative, validity and scale development. Psychological Reports. 1963;13:503–535. [Google Scholar]

- Lester D. Locus of control and suicidality. Perceptual & Motor Skills. 1999;89:1042. doi: 10.2466/pms.1999.89.3.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenstein D, Klein D, Pollack M. Follow-up study of formerly hospitalized voluntary psychiatric patients: The first two years. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1966;122:1102–1109. doi: 10.1176/ajp.122.10.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine E, Jonas H, Serper M. Interpersonal attributional biases in hallucinatory-prone individuals. Schizophrenia Research. 2004;69:23–28. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(02)00493-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman R. Future directions for research studies and clinical work on recovery from schizophrenia: Questions with some answers. International Review of Psychiatry. 2002;14:337–342. [Google Scholar]

- Liberman R, Kopelowicz A, Ventura J, Gutkind D. Operational criteria and factors related to recovery from schizophrenia. International Review of Psychiatry. 2002;14:256–272. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J. Myths and plain truths about schizophrenia epidemiology - the napr lecture 2004. Acta Psychiatra Scandinavica. 2005;111:4–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton M, Patterson T, Smith T, Grant I. The relationship among stress, depression, locus of control, irrational beliefs, social support, and health in alzheimer's disease caregivers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1995;183:78–85. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199502000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo SS, Taylor JL, Bentall RP. Poor me versus bad me paranoia and the instability of persecutory ideation. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 2006;79:271–287. doi: 10.1348/147608305X52856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryer M, Steinke J. Type of psychiatric disorder and locus of control. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1973;29:23–24. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(197301)29:1<23::aid-jclp2270290108>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Rotter J. Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs. 1966;80 1, whole no. 609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotter J. Internal versus external control of reinforcement: A case history of a variable. American Psychologist. 1990;45:489–493. [Google Scholar]

- Shirk H, Harrow M, Jobe T, Grossman L, Carter C, Faull R. The relationship of stress and anxiety in schizophrenia to psychosis: A 20-year multi-followup study. Scientific Proceedings of the 2005 Annual Meeting for the Midwestern Psychological Association; 2005. p. 109. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E. Research diagnostic criteria: Rationale and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1978;35:773–782. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770300115013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srole L. Mental health in the metropolis. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss J, Carpenter W. The prediction of outcome in schizophrenia: I characteristics of outcome. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1972;17:739–746. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1972.01750300011002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telesh K. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. Vol. 64. 2003. Relationships between a multidimensional construct of insight into mental illness, duration of illness, and locus of control; p. 433. [Google Scholar]

- Tooth B, Kalyanasundaram V, Glover H, Momenzadah S. Factors consumers identify as important to recovery from schizophrenia. Australasian Psychiatry. 2003;11(1):70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Twenge J, Zhang L, Im C. It's beyond my control: A cross-temporal meta-analysis of increasing externality in locus of control, 1960-2002. Personality & Social Psychology Review. 2004;8:308–319. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0803_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner R, Taylor D, Powers M, Hyman J. Acceptance of the mental illness label by psychotic patients: Effects on functioning. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1989;59:398–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1989.tb01675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigler E, Glick M. The developmental approach to adult psychopathology. The Clinical Psychologist. 2001;54(4):2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Westermeyer J, Harrow M. Predicting Outcome in Schizophrenics and Nonschizophrenics of Both Sexes: The Zigler-Phillips Social Competence Scale. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1986;95:406–409. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.95.4.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]