Abstract

Abscisic acid (ABA) signaling is important for stress responses and developmental processes in plants. A subgroup of protein phosphatase 2C (group A PP2C) or SNF1-related protein kinase 2 (subclass III SnRK2) have been known as major negative or positive regulators of ABA signaling, respectively. Here, we demonstrate the physical and functional linkage between these two major signaling factors. Group A PP2Cs interacted physically with SnRK2s in various combinations, and efficiently inactivated ABA-activated SnRK2s via dephosphorylation of multiple Ser/Thr residues in the activation loop. This step was suppressed by the RCAR/PYR ABA receptors in response to ABA. However the abi1–1 mutated PP2C did not respond to the receptors and constitutively inactivated SnRK2. Our results demonstrate that group A PP2Cs act as ‘gatekeepers’ of subclass III SnRK2s, unraveling an important regulatory mechanism of ABA signaling.

Keywords: protein phosphorylation, LC-MS, SnRK2, PYR1

As sessile organisms, plants have to rapidly recognize and adapt to environmental changes. The phytohormone abscisic acid (ABA) plays a central role in such responses (1, 2), and is also involved in many developmental processes (3) and defense systems (4). Thus, ABA functions as a key molecule that unifies and regulates biotic and abiotic stress responses and the developmental status of the plant. Hence, the biological and agricultural importance of ABA has led to extensive studies on its signaling mechanism, and many putative signal transducers have been reported (5). Although it has been difficult to integrate all of the current findings, significant progress was recently made by two independent research groups. They identified the RCAR/PYR family proteins as ABA receptors that inhibit protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C) in an ABA-dependent manner (6, 7). Among plant PP2Cs, a group A subfamily (e.g., ABI1 and ABI2) is annotated as negative regulators of the ABA response in seeds through to adult plants (5). Such PP2C-dependent negative regulation can be canceled by RCAR/PYR in response to ABA, leading to activation of some positive regulatory pathways (6, 7). Previously, we demonstrated that ABI1 interacts with a protein kinase, SRK2E (OST1/SnRK2.6) (8). SRK2E belongs to the SNF1-related protein kinase 2 (SnRK2) family, which is activated by ABA or osmotic stress and positively regulates the ABA response in various tissues (9–11). Furthermore, ABA-dependent activation of SRK2E was repressed in an abi1–1 mutant, suggesting that SnRK2 functions downstream of PP2C (8, 9). Based on these findings, a model was hypothesized in which RCAR/PYR and PP2C negatively regulate SnRK2 (7). However, there is no direct evidence demonstrating how PP2C regulates SnRK2, and the molecular process between them remains a question in ABA signaling. Our presented data clearly demonstrated the biochemical relation between PP2C and SnRK2 and elucidated an important regulatory mechanism of ABA signaling.

Results and Discussion

Requirement of SnRK2 Activity for ABA Responses.

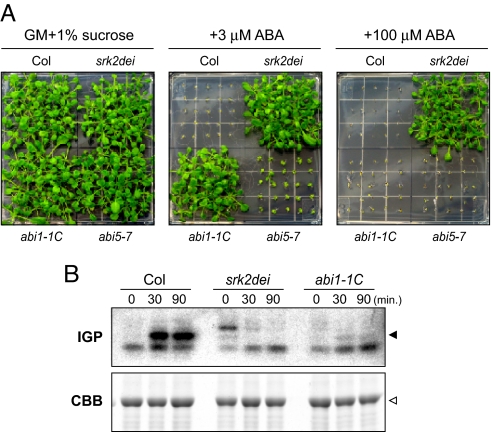

In Arabidopsis, subclass III of the SnRK2 family is composed of three proteins, namely SRK2D (SnRK2.2), SRK2I (SnRK2.3), and SRK2E (OST1/SnRK2.6). To further investigate the functions of SnRK2s, we established a triple knockout mutant for subclass III SnRK2s (srk2dei). Recently, some researchers independently established the same triple mutant, and its phenotype was thoroughly analyzed (12, 13). They showed the triple mutation completely impaired the ABA response, suggesting critical roles of subclass III SnRK2s and their fundamental redundancy in ABA signaling. In our study, we tested ABA responsiveness in the srk2dei mutant to compare with other ABA-insensitive mutants, abi1–1C and abi5–7. Consistent with a previous report, srk2dei showed marked ABA insensitivity, even in the presence of 100 μM ABA (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, in-gel phosphorylation assay demonstrated the loss of ABA-activated kinase activity (approx. 40 kDa) in srk2dei, and a low level of activity in abi1–1C (Fig. 1B), showing a correlation with their ABA sensitivity. Although some kinase activities were observed in srk2dei, they might be unknown kinases that were non-functional in wild-type plants. These data imply that all subclass III SnRK2s are strongly inhibited by abi1–1 mutation, and the SnRK2 activity should be major determinant of the ABA response in Arabidopsis.

Fig. 1.

Subclass III SnRK2s are essential for ABA responses. (A) Germination test to determine ABA sensitivity in the srk2dei triple mutant. Arabidopsis seeds of Col, srk2dei, abi1–1C, and abi5–7 were sown and grown for 2 weeks on GM agar medium containing 0, 3, or 100 μM ABA. (B) ABA-activated protein kinases in Col, srk2dei, and abi1–1C plants. Three-week-old plants were treated with 50 μM ABA for 0, 30, or 90 min. Upper panel shows in-gel phosphorylation (IGP) assay using histone as a substrate. Black arrow indicates ABA-activated protein kinase (≈40 kDa) overlapping with SnRK2s, and the open arrow indicates the RubisCo large subunit (≈50 kDa) in a CBB-stained gel. The results were confirmed through several replications.

Physical Interaction Between PP2C and SnRK2.

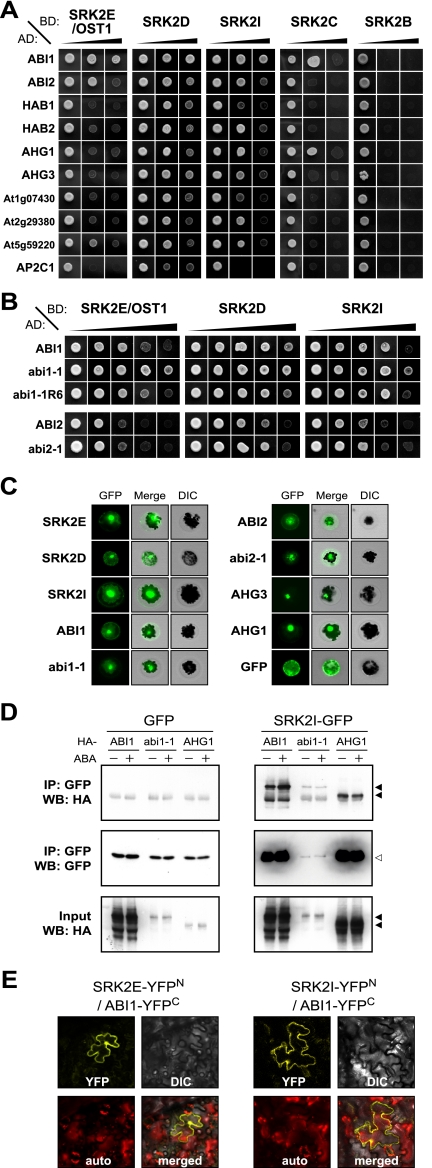

Our observations of srk2dei suggested that regulation of SnRK2 activity is a key to understanding how ABA signals are transmitted. As described above, we identified PP2C as a potential regulator of SnRK2, because ABI1 interacted with the domain II of SRK2E in the yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) system (8). In this study, we further tested five SnRK2s and 10 PP2Cs by Y2H assay. Consistent with our previous study, ABI1 strongly bound to SRK2E, and some other PP2Cs (e.g., ABI2 and At5g59220) also interacted with SRK2E (Fig. 2A). Compared with SRK2E, SRK2D and SRK2I showed a wide preference for various group A PP2Cs. Other SnRK2s (not subclass III) or an outgroup of PP2C, AP2C1 (group B), showed limited or no interaction (Fig. 2A). These results indicate that group A PP2Cs interact specifically with SnRK2s in various combinations. It should be noted that some of the Y2H results were not consistent with our previous study (8). This discrepancy may be related to technical problems, for which reason we confirmed our results through several replicates.

Fig. 2.

Group A PP2Cs interact with subclass III SnRK2s. (A) Yeast two-hybrid analysis of SnRK2s and PP2Cs. GAL4BD:SnRK2s and GAL4AD:PP2Cs were introduced to yeast cells as indicated. Black slopes indicate screening stringency of SD media supplemented with: left, -LW; center, -LWH + 10 mM 3-AT; right, -LWHA + 30 mM 3-AT. (B) Yeast two-hybrid analysis of PP2C mutations. ABI1, abi1–1, abi1–1R6, ABI2, and abi2–1 were tested against subclass III SnRK2s. The black slope demonstrates stringency of screening media: SD -LW, SD -LWH + 10 mM 3-AT, SD -LWHA + 30, 60, or 100 mM 3-AT from left to right. (C) Subcellular localization of GFP-tagged SnRK2 or PP2C proteins that were transiently expressed in Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts. (D) Co-immunoprecipitation of GFP-tagged SnRK2s and HA-tagged PP2Cs was performed using Arabidopsis protoplasts. Immunoprecipitates against anti-GFP antibody (IP) or crude extracts (input) were analyzed via Western blotting (WB) using anti-GFP or -HA antibodies. (E) BiFC analyses were performed for the pairs of SRK2E-YFPN/ABI1-YFPC or SRK2I-YFPN/ABI1-YFPC in epidermal cells of fava bean leaves. The photos were YFP, DIC, autofluorescence (auto) and merged images. The results were confirmed through several replications.

The physical interaction between SnRK2s and PP2Cs observed in the Y2H assay was partly supported by gene expression patterns and subcellular localizations. SRK2E and ABI1 were co-expressed in guard cells (Figs. S1 and S2) and were localized in the cytosol or nucleus (Fig. 2C). SRK2D and SRK2I were significantly expressed in seeds together with AHG1 or AHG3 which were localized in the nucleus predominantly (Fig. 2C and Fig. S1). These data were consistent with their regulatory roles in guard cells or seeds (11, 14, 15), showing a correlation between physiological function and Y2H results. To confirm these interactions in vivo, we performed co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) experiments using protoplasts expressing SRK2I-GFP and HA-tagged ABI1 or AHG1. As shown in Fig. 2D, these PP2Cs were co-immunoprecipitated with SRK2I in an ABA-independent manner, suggesting that they interact constantly in vivo. The co-expression of some pairs, for example, SRK2E and ABI1, was almost undetectable in protoplasts, making it impossible to demonstrate their interaction in Co-IP experiments. However, BiFC analysis confirmed the in planta interaction between SRK2E and ABI1 in the cytosol and nucleus, similar to SRK2I and ABI1 (Fig. 2E). The abi1–1 mutation causes a substitution of Gly to Asp (G180D) in the PP2C catalytic domain, which confers a dominant ABA-insensitivity by unknown mechanisms (16, 17). Although very little abi1–1 was produced in protoplasts, the data revealed that abi1–1 was able to bind to SRK2I constantly (Fig. 2D). This result was supported by the Y2H assay, in which abi1–1 and abi2–1 showed some enhanced interaction with SnRK2s, whereas abi1–1R6, a loss-of-function mutation for ABI1 (18), had no effect (Fig. 2B).

Group A PP2C Inactivates Subclass III SnRK2.

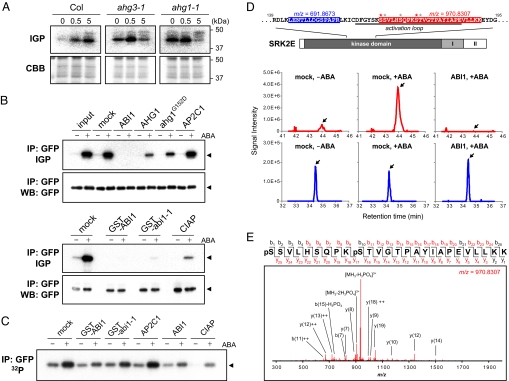

Previous studies showed that the ABA-responsive activation of SRK2E was inhibited in the abi1–1 mutant (8, 9). In addition, our data further demonstrated that all subclass III SnRK2s were inhibited by abi1–1 mutation (Fig. 1B), implying that subclass III SnRK2s function downstream of PP2C. To clarify this regulation, we examined SnRK2 activity in imbibed seeds from ahg1–1 and ahg3–1 which were loss-of-function mutations of PP2C causing ABA-hypersensitive germination (14, 15). The results revealed that approximately 40 kDa of protein kinase activity involving SnRK2 were hyperactivated in ahg1–1 and ahg3–1 (Fig. 3A), suggesting that PP2C negatively regulates SnRK2 activity. Next, we examined whether PP2C directly regulates SnRK2 activity using an in vitro phosphatase assay with recombinant PP2C proteins and GFP-tagged SnRK2s from Arabidopsis cells. SnRK2 activity was determined with an in-gel phosphorylation assay in which SnRK2-GFP was clearly activated by ABA (Fig. 3B and Fig. S3A). The activity of SRK2E or SRK2I was efficiently or significantly reduced by ABI1 or AHG1, and, surprisingly, ABI1-mediated inactivation was stronger than that of CIAP (Fig. 3B and Fig. S3A). Dominant-type PP2C mutants such as abi1–1 and ahg1G152D inactivated SnRK2 significantly (Fig. 3B and Fig. S3A), implying they are capable of regulating SnRK2 negatively as well as wild-type proteins. Because it was difficult to produce a tagless form of abi1–1, we used a pair of GST-tagged ABI1 and abi1–1 proteins in this study.

Fig. 3.

PP2C directly regulates SnRK2. (A) ABA-activated protein kinase activity in imbibed seeds of Col, ahg1–1, and ahg3–1 plants treated with 25 μM ABA for 0, 0.5, or 5.0 h. Upper panels show in-gel phosphorylation assay (IGP) using histone as a substrate. Lower panels are CBB-stained gel images. (B) Inactivation assay for SnRK2 by in vitro reaction with PP2Cs. SRK2E-GFP proteins were prepared by immunoprecipitation (IP) against an anti-GFP antibody from Arabidopsis cultured cells with or without ABA treatment. After incubation with recombinant PP2C proteins as indicated, SRK2E activity was monitored with an in-gel phosphorylation assay (IGP) using histone as a substrate. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed via Western blotting (WB) using an anti-GFP antibody. Arrows indicate SRK2E-GFP. (C) Dephosphorylation of 32P-labeled SRK2E-GFP by PP2Cs. Immunoprecipitated SRK2E-GFP was prepared from untreated or ABA-treated cultured cells labeled with 32P-phosphate, and incubated with PP2Cs as indicated. The phosphorylation level of SRK2E-GFP was monitored by autoradiography. (D) Immunoprecipitated SRK2E-GFP was analyzed with a nanoLC-MS/MS system. As examples, a non-phospho peptide of m/z = 691.8673 (blue) and a phospho-peptide of m/z = 970.8307 (red) are found in the structure of SRK2E and in extracted ion current (XIC) chromatograms. Arrows in XICs indicate the target peaks. Asterisks in red and black indicate probable phosphorylation sites detected in this study with the highest and less PTM scores, respectively. (E) An MS/MS spectrum derived from a phospho-peptide of m/z = 970.8307. Fragmented ions detected in this analysis are shown in red, and the top 15 ions were annotated in the spectrum. The results were confirmed through several replications.

Group A PP2C Directly Dephosphorylates Subclass III SnRK2.

Our data of in vitro inactivation assay (Fig. 3B) strongly suggested that PP2C-mediated inactivation of SnRK2 was given by dephosphorylation of an active form of SnRK2, which is highly phosphorylated in vivo (19, 20). To monitor the phosphorylation state of SnRK2, we prepared 32P-labeled SnRK2-GFP proteins from Arabidopsis cells. As shown in Fig. 3C or Fig. S3B mock lanes, the intensity of the signal corresponding to SRK2E/I-GFP increased and the position of SRK2I-GFP shifted slightly upon ABA treatment. When 32P-labeled SRK2E/I were incubated with ABI1, the signal intensity decreased and band shifting of SRK2I was not observed. GST-abi1–1 also dephosphorylated SRK2E/I (Fig. 3C and Fig. S3B), consistent with the results of in vitro inactivation assay (Fig. 3B and Fig. S3A). Similar results were obtained with AHG1 and SRK2I (Fig. S3B). Inconsistent with the in vitro inactivation assay, CIAP dephosphorylated SnRK2 more efficiently (Fig. 3C and Fig. S3B), suggesting that PP2C has specificity to critical sites for SnRK2 activity. Supporting this hypothesis, the radioactivity of SnRK2 remained basal even after incubation with PP2C. These results can be summarized; the ABA-responsive phosphorylation of SnRK2 in vivo was specifically reversed by PP2C in vitro. It is noteworthy that SnRK2 inactivation and dephosphorylation was not correlated with PP2C activity measured using a standard protocol. For example, GST-abi1–1 showed very low phosphatase activity to artificial substrates (Fig. S4), but strongly inactivated and dephosphorylated SnRK2 (Fig. 3 and Fig. S3). This inconsistency is probably due to the difference in compatibility to PP2C between native and artificial substrates. Our results suggest that abi1–1-type mutation does not affect strongly the PP2C activity for SnRK2.

We further analyzed SnRK2-GFP proteins using a nanoLC-MS/MS system to survey phosphorylation sites, and we detected several phospho-peptides that are responsive to ABA (Fig. 3D, Fig. S5, and Table S1). One of these, pSSVLHSDQPKpSTVGTPAYIAPEVLLKK, which spans the activation loop in SRK2E, was clearly upregulated by ABA but diminished after incubation with ABI1 (Fig. 3 D and E) or abi1–1 (Fig. S6). Although phosphorylation sites were not unambiguously identified with satisfactory probability scores in all peptides, we detected at least five phosphorylation sites in the kinase activation loop that were responsive to ABA, all of which were dephosphorylated by PP2C (Fig. S5 and Table S1). Some phosphorylation sites were previously reported in SRK2E and NtOSAK (20, 21), but their mutational analyses failed to produce an active form, suggesting technical difficulties for mapping critical residues for SnRK2 activation, like MAPKs. In our study, the PP2C-mediated dephosphorylation and inactivation of SnRK2 confirmed that SnRK2 activity was mainly regulated by reversible phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of the activation loop. Since PP2C-SnRK2 interactions are independent of ABA (Fig. 2D), PP2C is capable of inactivating SnRK2 even in the absence of ABA. We propose that this SnRK2 inactivation is an essential part of the PP2C-mediated negative regulation of ABA signaling, because SnRK2 regulates the majority of ABA responses (Fig. 1A). This PP2C-SnRK2 regulation reminds of two kinases related to plant SnRK2, yeast SNF1 and mammal AMPK, which are regulated by PP2C (22). There are several lines of evidence indicating that PP2Cs negatively regulate protein kinases in plants, for example, the Arabidopsis AP2C1 for AtMPK4/6 or the rice XB15 for XA21 receptor kinase (23, 24). Plants express a large, diverse family of PP2Cs (25), and these proteins may be involved in the regulation of many protein kinases.

Reconstitution of RCAR/PYR, PP2C, and SnRK2 Signaling Complex In Vitro.

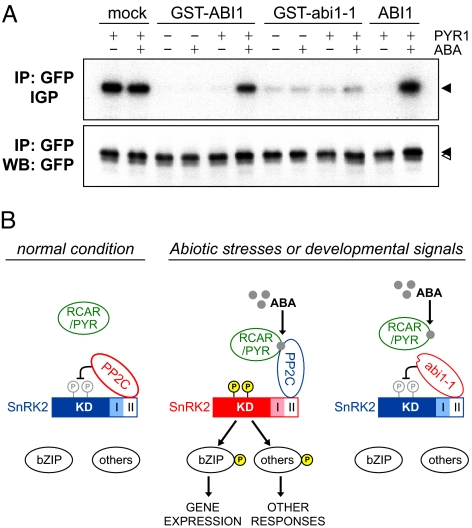

So far, our in vivo and in vitro experiments agree with the hypothesis that group A PP2Cs directly regulate subclass III SnRK2 activity via dephosphorylation. Recently, RCAR/PYR family proteins were identified as ABA receptors that inhibit PP2C activity in an ABA-modulated fashion (6, 7). Combining their findings and our own, we propose a signaling complex consisting of RCAR/PYR, PP2C, and SnRK2. To test this, we reconstituted these three components in vitro using recombinant ABI1, abi1–1, and PYR1 proteins, and GFP-tagged SnRK2s from Arabidopsis cells. After incubation with PYR1, PP2Cs, and SnRK2s in the presence or absence of ABA, SnRK2 activity was monitored via an in-gel phosphorylation assay. We found that PYR1 inhibited ABI1-mediated inactivation of SnRK2 in an ABA-dependent manner (Fig. 4A and Fig. S3C); however, abi1–1 inactivated SnRK2s even in the presence of PYR1 and ABA, consistent with previous data showing that abi1–1 and abi2–1 lacked RCAR/PYR-binding ability (6, 7). Thus, our results demonstrated that the abi1–1-type mutation negatively regulated SnRK2 in a constitutive fashion, resolving a long-standing puzzle of abi1–1 action.

Fig. 4.

(A) In vitro reconstitution analysis of the ABA signaling cascade. Immunoprecipitated SRK2E-GFP (ABA-activated) was incubated with GST-ABI1, GST-abi1–1, ABI1, or PYR1 proteins in the presence or absence of 10 μM ABA. SnRK2 activity was monitored with an in-gel phosphorylation assay (IGP) using histone as a substrate. Immunoprecipitates (IP) were checked by Western blot analysis (WB) against an anti-GFP antibody. Arrows indicate SRK2E-GFP. This result was confirmed through several replications. (B) Proposed model of the ABA signaling pathway in Arabidopsis. Left, in the absence of ABA, PP2C dephosphorylates and inactivates SnRK2. Middle, in the presence of ABA, RCAR/PYR interacts with PP2C, and SnRK2 is released from negative regulation and converted to an active form. The activated SnRK2 phosphorylates ABA-responsive transcription factors or unknown substrates to induce ABA responses. Right, even in the presence of ABA, the abi1–1 mutant of PP2C constitutively dephosphorylates SnRK2, consequently conferring dominant ABA insensitivity. In this model, PP2C constitutively binds to domain II at the C terminus of SnRK2. Red and blue colors indicate an active or inactive form, respectively.

A Simple Model of ABA Signaling in Plants.

Collectively, our data enables us to strengthen a hypothesized ABA signaling model previously proposed (7), and simplify the molecular process of ABA signaling to just four steps from perception to gene expression (Fig. 4B). First, PP2C interacts with domain II at the C terminus of SnRK2 (8); this interaction is constant and independent of ABA. In the absence of ABA, PP2Cs repress the ABA signaling pathway via the dephosphorylation and inactivation of SnRK2s. After the induction of free ABA by environmental or developmental cues, RCAR/PYR binds to PP2C (6, 7) and SnRK2 is released from PP2C-dependent negative regulation. This allows SnRK2 to phosphorylate downstream substrates, including bZIP transcription factors (AREB/ABFs) (26) etc., to activate ABA-responsive gene expression or other responses. In contrast, dominant mutations in PP2C, such as abi1–1, allow the protein to avoid RCAR/PYR-binding (6, 7), resulting in the constitutive inactivation of SnRK2s. At present, the mechanisms underlying the internal phosphorylation of SnRK2 remain unclear, although autophosphorylation is one of possible regulations (2). Further analysis will be required to clarify this issue.

We argue that the RCAR/PYR-PP2C-SnRK2 complex is the primary framework for ABA signaling, and that a conventional protein phosphorylation/dephosphorylation system, PP2C-SnRK2, provides a reversible regulatory module. Recently, group A PP2Cs and AREB/ABF bZIP transcription factors were found in Physcomitrella patens (27–29). Furthermore, our computational analysis detected subclass III SnRK2s in P. patens, but not in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Fig. S7). Thus, the PP2C-SnRK2-mediated signal transduction system may be conserved from bryophytes to higher plants, suggesting this system is an important acquired characteristic in the evolution of land plants with respect to drought tolerance.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials.

The srk2dei triple mutant was generated from srk2e (SALK_008068), srk2d (GABI-Kat_807G04), and srk2i (SALK_096546), which were obtained from public sources (ABRC or GABI_Kat). The abi1–1C was isolated from a genetic screen of Col background lines. The ABA response test was performed as described previously (15).

Plasmids.

In this study, a series of vector plasmids, such as pGBKT7 and pGADT7 (Clontech), pGEX6P (GE Healthcare), and the pGreen series (30), were converted to Gateway destination vectors. Gateway entry clones were prepared in the pENTR/D-TOPO or pDONR207 vector (Invitrogen) by insertion of cDNAs, SRK2E, SRK2D, SRK2I, SRK2C, SRK2B, ABI1, ABI2, HAB1, HAB2, AHG1, AHG3, At1g07430, At3g29380, At5g59220, AP2C1, and PYR1. Mutated PP2Cs [i.e., abi1–1 (G180D), abi1–1R6 (G307D), abi2–1 (G168D), and ahg1G152D] were generated using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) with entry clones as templates.

Yeast Two-Hybrid Analysis.

Yeast two-hybrid analysis was carried out using the MatchMaker GAL4 Two-Hybrid System 3 (Clontech) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A yeast strain (AH109) was transformed with various pairs of pGBKT7 vectors harboring SnRK2s and pGADT7 vectors harboring PP2Cs. Then, the transformants were tested on SD screening medium as indicated in Fig. 2.

In-Gel Phosphorylation Assay for Seed Proteins.

Dry seeds (50 mg) of Col, ahg1–1, and ahg3–1 were imbibed in water and placed at 4 °C for 3 days. Then imbibed seeds were treated with 25 μM (±)-ABA (Sigma) for 0, 1, and 5 h. Seeds were crushed by a mortar and pestle with silica sand in liquid nitrogen and homogenized in 100 μL extraction buffer containing 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 25 mM NaF, 50 mM, β-glycerophosphate, 10% glycerol, 2 mM DTT, and proteinase inhibitor mixture (Sigma). Crude extracts containing 50 μg total protein were loaded in 10% SDS-polyacrylamide and analyzed by in-gel kinase assay to check ABA-activated protein kinases as described previously (31).

Transient Expression in Arabidopsis Mesophyll Protoplasts.

The preparation of protoplasts from Arabidopsis rosette leaves and PEG-calcium transfection were performed according to ref. 32. We prepared pGreen0029 vectors harboring GFP, SRK2E-GFP, SRK2I-GFP, ABI1-HA, abi1–1-HA, or AHG1-HA. For subcellular localization, 20 μg plasmid DNAs were transfected into 3 × 104 protoplasts, and GFP signals were observed with a laser-scanning confocal fluorescence microscopy. For co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay, a total of 2 mg plasmid DNA mixture with SnRK2-GFP and PP2C-HA was transfected into 3 × 106 protoplasts. Crude extracts were obtained by homogenizing protoplasts in 1 mL extraction buffer supplemented with 100 mM KCl, 50 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Nonidet P-40 (IP buffer). Co-IP was performed with 100 μL Protein G Sepharose (GE Healthcare) and 1 μL polyclonal anti-GFP antibody (MBL), and aliquots were analyzed by Western blot analysis using monoclonal anti-GFP antibody (MBL) or anti-HA antibody (Covance).

Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC) in Fava Bean Leaves.

The cDNAs of SRK2E, SRK2I, and ABI1 were cloned into pUC-SPYNEGW or pUC-SPYCEGW (33). The constructs were delivered into leaf cells of fava bean (Vicia faba) by particle bombardment, as previously described (34), with modifications.

In Vitro Phosphatase Reaction.

Bacterial recombinant PP2C proteins and Arabidopsis T87 cells expressing SRK2E- or SRK2I-GFP were prepared as previously described (8, 14). T87 cells were treated with or without 50 μM ABA for 30 min, and IP was performed as described above. After washing, the buffer was exchanged for phosphatase reaction buffer (8), and then aliquots (30 μL) were mixed with 100 ng recombinant PP2C proteins, ABI1, AHG1, ahg1G152D, AP2C1, or 300 ng GST-ABI1 and GST-abi1–1, or 1 U CIAP (Toyobo). After incubation at 30 °C for 1 h, half aliquots were analyzed with an in-gel phosphorylation assay or Western blotting.

In Vivo Labeling of Arabidopsis Cells.

To check the phosphorylation status of SnRK2, Arabidopsis T87 cells expressing SRK2E- or SRK2I-GFP were labeled with 30 MBq/ml 32P-phosphate (NEX053H, Perkin-Elmer) for 2 h and then treated with or without 100 μM ABA for 30 min. IP and in vitro phosphatase reactions were performed as described above. After SDS/PAGE, radioactivity was detected by autoradiography.

In Vitro Reconstitution Assay of ABA Signaling Components.

Immunoprecipitated SRK2E- or SRK2I-GFP (bed vol. 30 μL) were incubated with 500 ng GST-ABI1 or GST-abi1–1, 100 ng ABI1, and 800 ng PYR1 proteins in the presence or absence of 10 μM ABA at 30 °C for 1 h. Recombinant PP2Cs and PYR1 were preincubated with ABA for 10 min in advance. Aliquots were analyzed by in-gel phosphorylation assay or Western blotting as described above.

NanoLC-MS/MS Analysis.

Immunoprecipitated SnRK2-GFP proteins were prepared as described above and analyzed with a nanoLC-MS/MS system (LTQ-Orbitrap, Thermo) according to ref. 35. The details of experiments are described in SI Text.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Mrs. Hiroko Kobayashi, Saho Mizukado (RIKEN), and Sumiko Onuma (Keio University) for technical assistance. We are grateful to ABRC and GABI-Kat project for providing Arabidopsis T-DNA-tagged mutants. We also thank Prof. Masaru Tomita at Keio University for his support. This work was partly supported by the RIKEN Plant Science Center, Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research for Young Scientists (B) to T.U. and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) to T.H. from MEXT, and research funds from Yamagata prefecture and Tsuruoka City to Keio University.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0907095106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K. Transcriptional regulatory networks in cellular responses and tolerance to dehydration and cold stresses. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:781–803. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sirichandra C, Wasilewska A, Vlad F, Valon C, Leung J. The guard cell as a single-cell model towards understanding drought tolerance and abscisic acid action. J Exp Bot. 2009;60:1439–1463. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finkelstein R, Reeves W, Ariizumi T, Steber C. Molecular aspects of seed dormancy. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2008;59:387–415. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mauch-Mani B, Mauch F. The role of abscisic acid in plant-pathogen interactions. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2005;8:409–414. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirayama T, Shinozaki K. Perception and transduction of abscisic acid signals: Keys to the function of the versatile plant hormone ABA. Trends Plants Sci. 2007;12:343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma Y, et al. Regulators of PP2C phosphatase activity function as abscisic acid sensors. Science. 2009;324:1064–1068. doi: 10.1126/science.1172408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park S, et al. Abscisic acid inhibits type 2C protein phosphatases via the PYR/PYL family of START proteins. Science. 2009;324:1068–1071. doi: 10.1126/science.1173041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoshida R, et al. The regulatory domain of SRK2E/OST1/SnRK2.6 interacts with ABI1 and integrates abscisic acid (ABA) and osmotic stress signals controlling stomatal closure in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:5310–5318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509820200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mustilli A, Merlot S, Vavasseur A, Fenzi F, Giraudat J. Arabidopsis OST1 protein kinase mediates the regulation of stomatal aperture by abscisic acid and acts upstream of reactive oxygen species production. Plant Cell. 2002;14:3089–3099. doi: 10.1105/tpc.007906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshida R, et al. ABA-activated SnRK2 protein kinase is required for dehydration stress signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002;43:1473–1483. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcf188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujii H, Verslues PE, Zhu J. Identification of two protein kinases required for abscisic acid regulation of seed germination, root growth, and gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:485–494. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujii H, Zhu J. Arabidopsis mutant deficient in 3 abscisic acid-activated protein kinases reveals critical roles in growth, reproduction, and stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:8380–8385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903144106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakashima K, et al. Three Arabidopsis SnRK2 protein kinases, SRK2D/SnRK2.2, SRK2E/SnRK2.6/OST1, and SRK2I/SnRK2.3, involved in ABA signaling are essential for the control of seed development and dormancy. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009;50:1345–1363. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshida T, et al. ABA-Hypersensitive Germination3 encodes a protein phosphatase 2C (AtPP2CA) that strongly regulates abscisic acid signaling during germination among Arabidopsis protein phosphatase 2Cs. Plant Physiol. 2006;140:115–126. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.070128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishimura N, et al. ABA-Hypersensitive Germination1 encodes a protein phosphatase 2C, an essential component of abscisic acid signaling in Arabidopsis seed. Plant J. 2007;50:935–949. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leung J, et al. Arabidopsis ABA response gene ABI1: Features of a calcium-modulated protein phosphatase. Science. 1994;264:1448–52. doi: 10.1126/science.7910981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meyer K, Leube MP, Grill E. A protein phosphatase 2C involved in ABA signal transduction in Arabidopsis thaliana. Science. 1994;264:1452–5. doi: 10.1126/science.8197457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gosti F, et al. ABI1 protein phosphatase 2C is a negative regulator of abscisic acid signaling. Plant Cell. 1999;11:1897–1910. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.10.1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kobayashi Y, Yamamoto S, Minami H, Kagaya Y, Hattori T. Differential activation of the rice sucrose nonfermenting1-related protein kinase2 family by hyperosmotic stress and abscisic acid. Plant Cell. 2004;16:1163–1177. doi: 10.1105/tpc.019943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burza AM, et al. Nicotiana tabacum osmotic stress-activated kinase is regulated by phosphorylation on Ser-154 and Ser-158 in the kinase activation loop. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:34299–34311. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601977200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belin C, et al. Identification of features regulating OST1 kinase activity and OST1 function in guard cells. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:1316–1327. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.079327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hardie DG, Carling D, Carlson M. The AMP-activated/SNF1 protein kinase subfamily: Metabolic sensors of the eukaryotic cell? Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:821–855. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schweighofer A, et al. The PP2C-type phosphatase AP2C1, which negatively regulates MPK4 and MPK6, modulates innate immunity, jasmonic acid, and ethylene levels in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:2213–2224. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.049585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park C, et al. Rice XB15, a protein phosphatase 2C, negatively regulates cell death and XA21-mediated innate immunity. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e231. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schweighofer A, Hirt H, Meskiene I. Plant PP2C phosphatases: Emerging functions in stress signaling. Trends Plants Sci. 2004;9:236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Furihata T, et al. Abscisic acid-dependent multisite phosphorylation regulates the activity of a transcription activator AREB1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1988–1993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505667103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knight CD, et al. Molecular responses to abscisic acid and stress are conserved between moss and cereals. Plant Cell. 1995;7:499–506. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.5.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rensing SA, et al. The Physcomitrella genome reveals evolutionary insights into the conquest of land by plants. Science. 2008;319:64–69. doi: 10.1126/science.1150646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Komatsu K, et al. Functional analyses of the ABI1-related protein phosphatase type 2C reveal evolutionarily conserved regulation of abscisic acid signaling between Arabidopsis and the moss Physcomitrella patens. Plant Mol Biol. 2009;70:341–357. doi: 10.1007/s11103-009-9476-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hellens RP, Edwards EA, Leyland NR, Bean S, Mullineaux PM. pGreen: A versatile and flexible binary Ti vector for Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. Plant Mol Biol. 2000;42:819–832. doi: 10.1023/a:1006496308160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Umezawa T, Yoshida R, Maruyama K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K. SRK2C, a SNF1-related protein kinase 2, improves drought tolerance by controlling stress-responsive gene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:17306–17311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407758101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoo S, Cho Y, Sheen J. Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts: A versatile cell system for transient gene expression analysis. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:1565–1572. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walter M, et al. Visualization of protein interactions in living plant cells using bimolecular fluorescence complementation. Plant J. 2004;40:428–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Myouga F, et al. A heterocomplex of iron superoxide dismutases defends chloroplast nucleoids against oxidative stress and is essential for chloroplast development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2008;20:3148–3162. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.061341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sugiyama N, et al. Phosphopeptide enrichment by aliphatic hydroxy acid-modified metal oxide chromatography for nano-LC-MS/MS in proteomics applications. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:1103–1109. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T600060-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.