Abstract

Tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) is a potentially lethal complication in cancer therapy. It may occur in highly sensitive tumors, especially in childhood cancer and leukemia, whereas, it is rare in the treatment of solid tumors in adults. TLS results from a sudden and rapid release of nuclear and cytoplasmic degradation products of malignant cells. The release of these can lead to severe alterations in the metabolic profile. Here, we present two cases of large hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) treated by transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) that resulted in TLS. Although TLS rarely happens in the treatment of adult hepatic tumor, only a few cases have been reported. We should keep in mind that all patients with HCC, particularly those with large and rapidly growing tumors, must be closely watched for evidence of TLS after TACE.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Therapeutic chemoembolization, Tumor lysis syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common neoplasm worldwide, and the third most common cause of cancer-related death. Despite the development of several methods for unresectable HCC, transarterial embolization (TAE) is the most widely used[1]. Although TAE is an effective modality, there are several potential side effects such as hepatic failure, internal bleeding, liver abscess, biliary tract injury, and renal failure[2]. Among these varied complications, tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) is easily neglected and may be fatal.

TLS was first reported in 1929, and is defined by the release of intracellular components into the bloodstream as a result of massive lysis of malignant cells after effective therapy. The release of these components can cause severe metabolic alterations, characterized by hyperuricemia, hyperkalemia, hyperphosphatemia, and hypocalcemia[3-5]. Hyperuricemia is caused by purine degradation and can lead to precipitation of uric acid crystals in the kidney collecting tubules, which results in obstructive nephropathy[6]. Hyperkalemia, following potassium effusion from the cytoplasm, may lead to cardiac arrhythmia and arrest. Therefore, TLS can lead to acute renal failure and can be life-threatening, if it is not recognized early and treated. It is most commonly observed following chemotherapy for high-grade lymphoproliferative malignancy, such as acute lymphocytic leukemia and Burkitt lymphoma[7,8]. Although TLS also has been reported in many different types of solid tumors, including lung and breast carcinoma[9-11], it is still very rare in the treatment of HCC with transarterial chemoembolization (TACE). As far as we know, only a few cases have been reported in the English-language literature[12,13].

Here, we report two cases of acute TLS in patients with HCC following TACE, and review the literature.

CASE REPORT

Case 1

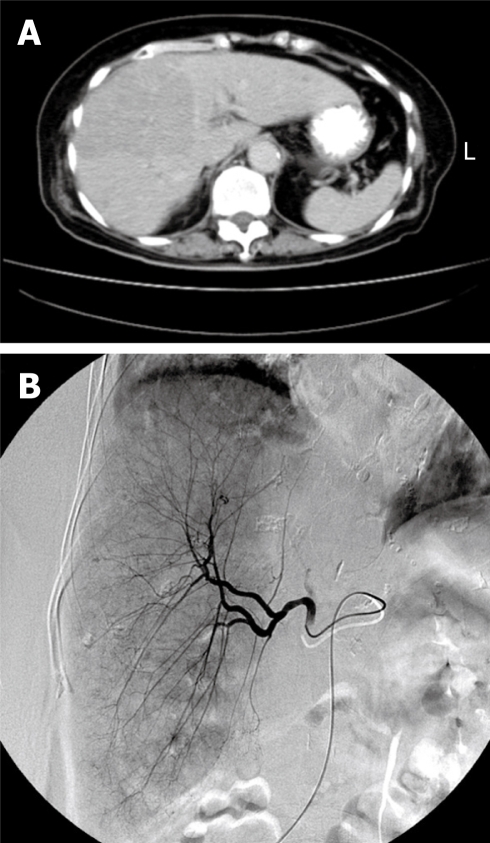

A previously well 76-year-old woman suffered from epigastric fullness and dull pain for about 1 mo. Abdominal sonography revealed a large liver tumor that occupied the majority of the right lobe (Figure 1A), and biopsy of the tumor showed HCC. TACE with 20 mg adriamycin (Figure 1B) was performed during admission. The patient developed acute renal insufficiency on the next day. Contrast-induced acute renal failure was suspected in the beginning, but the symptom did not improved after adequate resuscitation. On the third day post-TACE, the acute renal failure worsened. In addition, hyperuricemia (16.6 mg/dL), hyperkalemia (5.7 mEq/L) and hypocalcemia (6.8 mg/dL) were noted later. Under suspicion of TLS, oral allopurinol and urine alkalization, combined with hemodialysis, were given immediately. The patient’s renal function stabilized and the urine output increased progressively after treatment. Unfortunately, severe aspiration pneumonia developed during this period, and the patient expired because of sepsis on day 17 after TACE.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography scan obtained before TACE showed a large HCC over the right lobe (A), and TACE revealed hypervascularization of the tumor (B).

Case 2

A 56-year-old male patient was a hepatitis B virus carrier. Regular surveillance revealed a large hepatic tumor over segment 6 and a high α-fetoprotein level (247 ng/dL). Under suspicion of HCC, he was admitted for further treatment. After discussion with the hepatobiliary team, TACE (10 mg lipiodol + 20 mg adriamycin) was suggested as the treatment of choice. Oliguria occurred on the same night. The previous experience reminded us about the possibility of TLS in such a situation. We checked the laboratory profile for TLS immediately. Hyperuricemia (15.1 mg/dL), hyperphosphatemia (4.7 mg/dL) and hypocalcemia (6.6 mg/dL) were noted, and TLS was diagnosed. After standard treatment including oral allopurinol and urine alkalization, this patient’s symptoms improved dramatically. Finally, he was discharged on day 6 post-TACE without any other complication.

DISCUSSION

HCC is the fifth most common neoplasm in worldwide, and the third most common cause of cancer-related death. Only a minority of HCCs are diagnosed at an early stage for potentially curative therapy such as surgical resection or local ablation[1]. Several methods have been developed for unresectable HCC, including radiotherapy, chemotherapy and TACE. Among the various treatments, TACE has shown evidence of a beneficial survival effect compared with other methods[1,2]. As the most widely used treatment for advanced HCC, TACE still has some complications. Common adverse effects of TACE include liver dysfunction, post-embolization syndrome, hepatic infarction, and liver abscess. Besides these, TLS is a very rare and easily neglected complication.

The first two cases of TACE-induced TLS were reported by Burney in 1998, and both had large HCCs (> 5 cm in size)[12]. As in our situation, the first case was diagnosed too late and the patient died. The second patient’s syndrome was detected early and treated appropriately. Another case report was published by Sakamoto et al[13]. This patient had a large HCC > 20 cm in size. After treatment with TACE, the patient also died of acute TLS. Both authors concluded that TLS is a possible and lethal complication of TACE for large HCC.

TLS is a known consequence of treatment of hematological malignancies such as leukemia and lymphoma[7,8]. In general, TLS is less likely to occur in adult patients with solid tumors. However, some solid malignancies in adults, such as breast cancer, small cell lung cancer, seminoma, metastatic Meckel’s cell tumor, medulloblastoma, and even hepatoma have been reported to be the cause of TLS[9-11]. TLS may occur after various treatments of HCC, including radiofrequency ablation[14], oral thalidomide[15] and TACE[12,13].

TLS arises from spontaneous cell death or within the first few days after cytotoxic therapy, and results from rapid tumor destruction. It leads to hyperuricemia, hyperkalemia, hyperphosphatemia, hypocalcemia, or often, acute renal failure[3-6]. Early identification of patients at risk and prevention of TLS development is critical. Acute renal failure may occur from intravascular volume depletion or from deposition of uric acid and calcium phosphate crystals in the renal tubules. Without prompt and proper management, derangements of TLS can result in death, as in case 1. Early recognition and treatment will reduce the risk of this fatal complication. For early recognition, it is essential to monitor patients at high risk, especially during the early course of treatment. Traditionally, patients with large tumor burdens and/or rapidly dividing tumors are at greatest risk for TLS. Other risk factors include chemosensitive tumors, large area of tumor necrosis, and pretreatment renal dysfunction. Serum potassium, uric acid, calcium, phosphate and lactate dehydrogenase level, and renal function should be monitored intensively in these high-risk patients after cancer therapy[3-5].

According to the Cairo-Bishop classification, TLS is defined as a 25% change or a level above or below normal for any two or more serum values of uric acid, potassium, phosphate, and calcium within 7 d after cancer therapy[5] (Table 1). The principles of treatment of TLS should address three critical areas: hydration, correction of metabolic abnormalities, and aggressive treatment of renal failure. Aggressive fluid administration has been recommended in all high-risk patients. Volume expansion with isotonic saline can reduce serum concentrations of uric acid, phosphate and potassium. As renal blood flow, glomerular filtration rate, and urine output are all increased, the concentration of solutes in the renal tubules is decreased, which makes precipitation less likely[16]. Prevention and treatment of abnormal metabolites are the next step, especially hyperuricemia. Uric acid crystals can precipitate in renal tubules and cause obstructive nephropathy and renal failure. Oral or intravenous allopurinol (100 mg/m2 every 8 h) is recommended for the treatment of hyperuricemia. Recently, another urate oxidase (rasburicase; 0.05-0.2 mg/kg) was demonstrated to be more effective than allopurinol for the treatment of hyperuricemia[3-6]. If obstructive nephropathy persists and progresses to acute renal failure, aggressive hemodialysis should not be delayed[16].

Table 1.

Cairo-Bishop definition of TLS

| Uric acid | ≥ 8.0 mg/dL or 25% increase from baseline |

| Potassium | ≥ 6.0 mEq/L or 25% increase from baseline |

| Phosphorus | ≥ 4.5 mg/dL or 25% increase from baseline |

| Calcium | ≥ 7.0 mg/dL or 25% decrease from baseline |

Oliguria is not a rare occurrence post-TACE. The most common cause is radiocontrast-induced renal insufficiency. However, oliguria also can be one of the early clinical signs of TLS[5]. The incidence of acute renal insufficiency caused by TACE per se has been shown to be 3%-8% for each treatment session[17]. It is much more common than that induced by TLS. Adequate hydration is sufficient to overcome this complication. Therefore, many physicians may misdiagnose oliguria as a sign of contrast-induced renal insufficiency and delay proper treatment. Hydration alone is not sufficient for the treatment of TLS. Correction of abnormal metabolites, such as reduction of uric acid level, is another essential feature. If we overlook the potential risk of TLS, the results can be tragic.

In conclusion, although rare, TLS can occur after TACE of HCC in adults. Pretreatment evaluation of risk factors, including large tumor size, rapid tumor growth, and renal insufficiency should be completed. Close monitoring after TACE in these high-risk patients is warranted. When TLS develops, effective treatment, including adequate hydration, oral medication (allopurinol and/or urate oxidase) or hemodialysis, should be undertaken immediately.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Nahum Méndez-Sánchez, MD, PhD, Departments of Biomedical Research, Gastroenterology & Liver Unit, Medica Sur Clinic & Foundation, Puente de Piedra 150, Col. Toriello Guerra, Tlalpan 14050, México, City, México

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2003;362:1907–1917. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14964-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lau WY, Yu SC, Lai EC, Leung TW. Transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202:155–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.06.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidson MB, Thakkar S, Hix JK, Bhandarkar ND, Wong A, Schreiber MJ. Pathophysiology, clinical consequences, and treatment of tumor lysis syndrome. Am J Med. 2004;116:546–554. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Del Toro G, Morris E, Cairo MS. Tumor lysis syndrome: pathophysiology, definition, and alternative treatment approaches. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2005;3:54–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cairo MS, Bishop M. Tumour lysis syndrome: new therapeutic strategies and classification. Br J Haematol. 2004;127:3–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alkhuja S, Ulrich H. Acute renal failure from spontaneous acute tumor lysis syndrome: a case report and review. Ren Fail. 2002;24:227–232. doi: 10.1081/jdi-120004100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen LF, Balow JE, Magrath IT, Poplack DG, Ziegler JL. Acute tumor lysis syndrome. A review of 37 patients with Burkitt's lymphoma. Am J Med. 1980;68:486–491. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(80)90286-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Altman A. Acute tumor lysis syndrome. Semin Oncol. 2001;28:3–8. doi: 10.1016/s0093-7754(01)90254-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sewani HH, Rabatin JT. Acute tumor lysis syndrome in a patient with mixed small cell and non-small cell tumor. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:722–728. doi: 10.4065/77.7.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalemkerian GP, Darwish B, Varterasian ML. Tumor lysis syndrome in small cell carcinoma and other solid tumors. Am J Med. 1997;103:363–367. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rostom AY, El-Hussainy G, Kandil A, Allam A. Tumor lysis syndrome following hemi-body irradiation for metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2000;11:1349–1351. doi: 10.1023/a:1008347226743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burney IA. Acute tumor lysis syndrome after transcatheter chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma. South Med J. 1998;91:467–470. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199805000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakamoto N, Monzawa S, Nagano H, Nishizaki H, Arai Y, Sugimura K. Acute tumor lysis syndrome caused by transcatheter oily chemoembolization in a patient with a large hepatocellular carcinoma. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30:508–511. doi: 10.1007/s00270-005-0240-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lehner SG, Gould JE, Saad WE, Brown DB. Tumor lysis syndrome after radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:1307–1309. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee CC, Wu YH, Chung SH, Chen WJ. Acute tumor lysis syndrome after thalidomide therapy in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncologist. 2006;11:87–88; author reply 89. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-1-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sallan S. Management of acute tumor lysis syndrome. Semin Oncol. 2001;28:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0093-7754(01)90255-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huo TI, Wu JC, Lee PC, Chang FY, Lee SD. Incidence and risk factors for acute renal failure in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing transarterial chemoembolization: a prospective study. Liver Int. 2004;24:210–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2004.00911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]