Abstract

Objective

Single-year estimates of health disparities in small racial/ethnic groups are often insufficiently precise to guide policy, whereas estimates that are pooled over multiple years may not accurately describe current conditions. While collecting additional data is costly, innovative analytic approaches may improve the accuracy and utility of existing data. We developed an application of the Kalman filter in order to make more efficient use of extant data.

Data Source

We used 1997–2004 National Health Interview Survey data on the prevalence of health outcomes for two racial/ethnic subgroups: American Indians/Alaska Natives and Chinese Americans.

Study Design

We modified the Kalman filter to generate more accurate current-year prevalence estimates for small racial/ethnic groups by efficiently aggregating past years of cross-sectional survey data within racial/ethnic groups. We compared these new estimates and their accuracy to simple current-year prevalence estimates.

Principal Findings

For 18 of 19 outcomes, the modified Kalman filter approach reduced the error of current-year estimates for each of the two groups by 20–35 percent—equivalent to increasing current-year sample sizes for these groups by 56–135 percent.

Conclusions

This approach could increase the accuracy of health measures for small groups using extant data, with virtually no additional cost other than those related to analytical processes.

Keywords: Health disparities, Chinese, American Indians, borrowing strength, cross-sectional data

Eliminating racial/ethnic health disparities is a major federal policy goal; however, most national health surveys have limited ability to assess the health of racial/ethnic population subgroups (e.g., national origin subgroups of Hispanic ethnicity or Asian race) (Waksberg, Levine, and Marker 2000) or to measure progress toward those goals. The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), the primary source of information on the nation's health (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2007), has been successfully used for innovative analyses in small areas (e.g., Long, Graves, and Zuckerman 2007) and can support simple analyses for racial/ethnic subgroups; sample sizes are insufficient for detailed analyses of subgroups other than Mexican Americans using traditional techniques. The Census 2000 and the American Community Survey provide sufficient sample sizes for accurate estimates for American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/AN) and Asian national origin subgroups, but neither collects much data on health. In a time of limited survey budgets but pressing policy needs, the need to increase accuracy without generating additional costs cannot be overstated.

Several approaches to combining data have been used to make estimates about the health of racial/ethnic populations. One approach is to “borrow strength” from larger groups (Rao 2003), that is, to combine direct estimates based on the data collected from the exact population of interest with indirect estimates based on related data, such as data from other geographic areas, subgroups, or time periods. While indirect estimates may contain bias if the related data differ systematically from the data of interest, in combination with direct estimates they can often improve overall accuracy by substantially decreasing the variance of a combined estimator.1

Borrowing strength from other geographic areas, often known as small-area estimation, is useful when one is trying to estimate in smaller geographic areas (e.g., Mendez-Luck et al. 2007), but of limited use for national estimates. Borrowing from other racial/ethnic groups by incorporating the overall population prevalence into weighted estimates can improve the precision of estimates for smaller racial/ethnic groups (which typically have smaller sample sizes in general national surveys), but because the overall population mean is dominated by non-Hispanic whites and other larger groups, this approach biases estimators of between-group health differences toward zero, underestimating the disparities between them. Such a bias directly confounds policy questions of interest. Combining multiple years of data within racial/ethnic subgroups (borrowing strength over time) can improve estimates without systematically underestimating differences. Simply averaging past and current years to estimate the present prevalence can introduce substantial bias if the prevalence changes over time, as obesity and diabetes have recently. What is needed is a method that improves the accuracy of prevalence estimates and means for national racial/ethnic groups in the most recent year for which data are available (hereafter referred to as the “current” year) that (a) does not systematically under- or overestimate differences between groups and (b) allows for time trends.

We describe an alternative method for improving estimates for small population subgroups, based on the Kalman filter. This approach “borrows strength” across years—combining estimates from multiple years, but giving the greatest weight to the current year. The Kalman filter (Kalman 1960), which originated as a recursive computational algorithm to estimate the state of a process and “filter” out “noise” (as opposed to signal) in engineering applications, provides a general set of tools applicable to a variety of nonengineering settings. It views a survey estimate as a noisy measure of an underlying population mean that is influenced by its own past values. Treating present values as “updates” from the past allows us to smooth the estimate of the present using the past. In particular, it provides an optimal means for combining data across years to capture under a statistical model: (a) autocorrelated time-varying means for each racial/ethnic group that transition smoothly across years; (b) individual variance within these groups around the means (Blight and Scott 1973; Binder and Dick 1989; Lind 2005;); and (c) errors in the estimates of the annual group means resulting from sampling individuals from the group population.

For estimating disparities, more general recommendations by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) suggest using the difference between a given group (e.g., AI/AN or Chinese) and the group with the most salutary level of a given outcome among those groups with a relative standard error (RSE) of <10 percent for that outcome (Keppel, Pearcy, and Klein 2004). Such an approach ensures that the reference group is itself well estimated and that the error in disparity estimates involving rare racial/ethnic groups such as AI/AN and Chinese in the present application is primarily a function of the error in the estimates for these rare groups themselves. However, relatively small sample sizes for both AI/AN and Chinese American subgroups mean that simple 1-year direct estimates for both have RSEs exceeding the recommended maximum of 30 percent for several health outcomes.

We use data from AI/AN and Chinese American samples in the NHIS to demonstrate the utility of the modified Kalman filter (MKF) for health-disparities research. Each group (1) represents  percent of the U.S. population, (2) has been identified as a distinct subgroup in NHIS data for a number of years, and (3) has about 200 observations annually.

percent of the U.S. population, (2) has been identified as a distinct subgroup in NHIS data for a number of years, and (3) has about 200 observations annually.

METHODS

Accuracy and Precision

The goal of pooling data across years is to reduce error in the current-year estimate by using more related data than is available with just the current-year sample. The resulting estimate is a weighted average of the mean for the current year and the means from prior years. If, however, the true (population) current-year mean is different from past year means, then pooling estimates from the past with the current-year sample mean will cause the combined estimate to deviate systematically from the true current-year mean, causing our estimate to be biased. The accuracy, or the extent to which there is a small overall distance between our estimate and the true value, can nevertheless be better than the accuracy of the current-year sample mean, if this bias (systematic error) is smaller than the reduction in the sample size-based variance (unsystematic error) that results from combining data across years.

Accuracy is often the most policy-relevant measure of an estimator because it describes how close the estimates will be to the quantities of interest. Precision is often used as the measure of an estimator's quality because estimates are assumed to have no bias or because biased estimators are not considered, even when more accurate. Biased estimates are often assumed inferior, but with small sample sizes, certain biased estimators can be more accurate (closer to the truth on average) than traditional unbiased estimators. In the present context, bias does not indicate a systematic tendency to over- or underestimate for any group, but rather a conservative “shrinking” toward trend lines based on past data. Consequently, accuracy is the more relevant measure of an estimator's quality in this application. Accuracy is generally measured by the mean squared error (MSE), which equals the expected value of the square of the difference between an estimate and the true but unknown parameter of interest (e.g., the current-year population mean).

Data

The NHIS is a multistage, national probability survey, administered as a repeated annual cross-section. We used data from 8 years of the NHIS (1997–2004), restricting our analysis to the 258,279 total cases in the adult sample. We collapsed approximately 20 race/ethnicity categories to obtain 11 subgroups with stable 1997–2004 definitions: four Hispanic subgroups (subdivided by national origin): Hispanic Mexican, Hispanic Puerto Rican, Hispanic Cuban, Hispanic other national origin; and seven non-Hispanic racial groups: white, black, Chinese, Asian Indian, Filipino, AI/AN, and Other (includes Pacific Islander, other Asian, and multiracial). The Chinese category was available consistently for 1997–2004. We created a consistent 1997–2004 AI/AN subgroup by combining 1997–2004 Native American, 1997–1998 Aleut and Eskimo, and 1999–2004 Alaskan Native.

We selected a total of 19 health outcomes (continuous and dichotomous) based on 23 original indicators (we collapsed four indicators of heart disease into one indicator2) (Table 1). The 19 outcomes include measures of utilization, number of workdays lost, number of functional limitations, body mass index (BMI), history of specified chronic diseases, recent episodes of acute illnesses, and substance use.

Table 1.

Mean Increase in Equivalent Sample Size from MKF for the 19 NHIS Outcomes (2004 AI/AN and Chinese)

| Outcome | Mean Amount by Which MKF Multiplies the Equivalent Sample Size of Single-Year Estimates |

|---|---|

| Prevalence estimates | |

| Any heart disease | 2.29 |

| Any binge drinking | 2.15 |

| Asthma | 2.07 |

| Bronchitis | 2.21 |

| Cancer | 2.29 |

| Diabetes | 1.60 |

| Emphysema | 1.92 |

| Any functional limitation | 1.63 |

| Hay fever | 2.04 |

| Hypertension | 2.28 |

| Kidney disease | 2.30 |

| Sinusitis | 1.94 |

| Smoke, current | 1.56 |

| Stroke | 2.35 |

| Ulcer | 2.11 |

| Means | |

| Mean inpatient days | 2.03 |

| Mean BMI | 1.07 |

| Mean outpatient visits | 1.57 |

| Mean workday loss | 2.16 |

Note. Design effects from sample design are not incorporated.

AI/AN, American Indians/Alaska Natives; BMI, body mass index; MKF, modified Kalman filter; NHIS, National Health Interview Survey.

A Statistical Model of Racial/Ethnic Group Means

We seek to use survey data to estimate the current-year average health of racial/ethnic subgroups. We first posit that if fully observed, the average health of a group would vary from year to year, possibly with a trend in which a health indicator improves or declines over time due to changes in lifestyle, medical advances, demographics, or other unmeasured factors. The true means of health indicators would thus vary around that trend line across time. However, deviations from the trend line would likely be similar in consecutive years because the health of populations tends to move from its previous states rather than being created anew each year.

Following this heuristic description of the time evolution of the average health of a racial/ethnic population, we use model (1) to describe the 88 group-year means3 (8 years × 11 racial/ethnic groups) for a given outcome:

| (1) |

where meanit equals the mean for the racial/ethnic subgroup i=1, …, 11 in year t=1, …, 8 and sample meanit equals the estimated sample mean for the subgroup. As per our description above, the mean depends on racial/ethnic group-specific independent linear trends, αI +βit, and group-specific annual deviation from those trends, γit. To allow deviations from consecutive years to be similar, we assume a first-order autoregressive “AR(1)” correlational structure for the annual deviations within each group, γit=ργit−1+ξit. The first component (ργit−1) describes the transition from the past, and positive autocorrelation (a positive ρ) implies a “sticky” tendency for successive group-year means to stay on the same side of the trend line as the previous year's value. The second component (ξit), called the “innovation,” describes how the current-year mean differs from the trend and the recent past. The innovation is assumed to have mean zero, so that any year deviation might be higher or lower than the projection of the past, with a variance of τ2 (the innovation variance). Model (1) also assumes that, due to sampling of the population, the sample mean equals the population mean plus an error term (ηit), with sampling variance νit. Because the sample mean is the average of individual responses, we assume  , where

, where  is the effective sample size for estimating the mean (the nominal sample size divided by the design effect for complex samples), and σ2 is the variance of individuals' outcomes around the group mean. Table 2 summarizes the parameters in our model.

is the effective sample size for estimating the mean (the nominal sample size divided by the design effect for complex samples), and σ2 is the variance of individuals' outcomes around the group mean. Table 2 summarizes the parameters in our model.

Table 2.

Summary of Model Parameters

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| αi | Intercept for the linear trend in annual mean health outcomes for subgroup i |

| βi | Slope for the linear trend in annual mean health outcomes for subgroup i |

| σ2 | Variance of individuals' outcomes around the group mean |

|

The effective sample size for the current-year sample mean equals the sample size for the group in year t divided by the design effect due to sample design |

| νit | Sampling variance of the current-year sampling mean, νit=σ2/

|

| ρ | The autocorrelation parameter: the correlation between the current-year and prior-year populations for the subgroup—describes the dependency of the current-year mean on the past |

| τ2 | The innovation variance—the variance in the unique current-year component of the annual deviation of the group mean around its linear trend |

For simplicity and more precise estimates, we assume that neither the AR(1) parameter, ρ, nor the innovation variance, τ2, differs among the racial/ethnic groups for a given outcome.4 Larger values of τ2 indicate that health outcomes in the current year are very specific to that year and distinct from the past. Larger positive values of ρ indicate strong local correlation in deviations from the linear trend—being above the linear trend one year is predictive of being above that same trend in the next year.

MKF

In the MKF approach we present here, we first use linear regression to estimate a linear trend over time within each racial/ethnic group (αI+βit). We then apply the Kalman filter to the residuals of this model to estimate the annual deviations (γit).

The MKF uses the past data to predict the current value on the basis of the strength of the autocorrelation and then combines this prediction with the true current estimate using weights that depend on the innovation variance, with greater weight on the current-year sample mean when the innovation variance is large.

Appendix SA2 provides additional detail about the model, including (a) the model for group sample means, (b) the updating formula that models residuals of the group-year mean, and (c) the fitting of the MKF. Appendix SA3 describes the calculation of the accuracy of the MKF and alternative estimators in terms of MSE.

Assessment of the MKF

To assess the performance of the MKF relative to direct estimation, we first compare 2004 MKF estimates of AI/AN and Chinese health to simple 2004 estimates for the 19 NHIS outcomes examined. To explore the relative performance of the MKF more broadly, we then empirically investigate the MSE of both the MKF and the current-year mean at a grid of values representing four key parameters, with the grid values chosen from our analysis of the NHIS.

Comparing MKF and Simple Estimates for NHIS Outcomes

The NCHS recommends RSEs (Keppel et al. 2005) of 10 percent or less as a goal for prevalence estimates and sets RSEs of 30 percent as an upper bound for an estimate to have any policy utility. Applying these heuristics to MKF estimates requires us to use the MSE-based generalization of the RSE, which is the relative root MSE (RRMSE=root MSE/point estimate) in place of the RSE henceforth. The RRMSE is the same as the RSE for simple 1-year estimates and is analogous to the RSE for MKF estimates, making for straightforward comparison of MKF and simple estimates.5

For each NHIS outcome we compute (a) point estimates, (b) the RRMSE, and (c) the width of error bands (equal to the point estimate±1.96 times the RMSE) for MKF and direct 1-year estimates of 2004 values for the 19 NHIS outcomes for AI/AN and Chinese. For the MKF, the error bands are not confidence intervals per se but provide comparable measures of the likely errors in the estimates.

The MKF is applicable to surveys such as the NHIS with clustering by PSUs and other aspects of complex survey design, as noted in Appendix SA2. Actual NHIS effective sample sizes vary by outcome and subgroup as a function of clustering in the complex survey design. For the sake of simplicity and uniformity of comparisons, we base all measures of error on what would be achieved with an effective sample size of 200 responses per outcome annually for both AI/AN and Chinese. These are similar to the nominal NHIS sample sizes for the years in question; actual effective sample sizes6 are typically about 133 and rarely exceed 200. This approach understates the absolute variability of both the traditional estimates and the MKF alternative, but it simplifies presentation and provides a somewhat conservative estimate of the relative reductions in errors that the MKF can provide because the MKF produces greater proportionate gains at smaller effective sample sizes.

Empirical Investigation

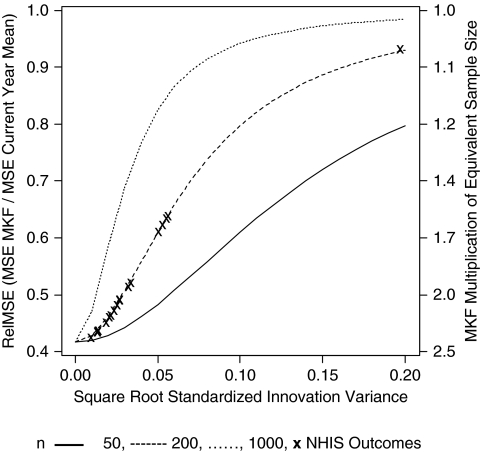

The NHIS study describes the performance of the relative MKF and the current-year mean at a limited number of values for the parameters that influence the estimators' accuracy. To study the relative accuracy of the two estimators more broadly, we use the analytic formulas from Appendix SA3 to calculate the MSE of the MKF and the current-year mean at alternative values of (a) the annual (effective) sample size of the group of interest (N=50, 200, or 1,000), (b) the AR1 parameter, ρ (0.00, 0.05, …, 0.95), (c) the annual slope of the trend line standardized by individual-level standard deviations within group and year, β/σ (0.000, 0.001, …, 0.020), and (d) the standardized innovation variance, equal to the innovation variance divided by the individual-level variance, τ2/σ2 (0.00, 0.012, …, 0.202). The values for parameters (b)–(d) were chosen by estimating the parameters for the 19 outcomes and all 11 groups of the NHIS and using the range in the estimates to set the range for our empirical study. Using the four-way crossing of the parameters' values, we created a grid of 26,240 scenarios and calculated the MSE for both estimators at each grid point. We use the relative MSE (relMSE), equal to the ratio of the MSE from the MKF to the MSE of the 1-year direct estimate, to compare the accuracy of the two estimators. Smaller values indicate greater gains in accuracy for the MKF compared with the current-year mean. The reciprocal of relMSE is the ratio of equivalent sample sizes in terms of accuracy from using MKF rather than the current-year mean, where the equivalent sample is the (effective) sample size required in the current year to yield the same accuracy with the sample mean as the MKF applied to all years of data.

RESULTS

Comparing Direct One-Year and MKF Estimates of the 19 NHIS Outcomes

The MKF improves accuracy over single-year prevalence estimates for all the 19 outcomes (see Table 1). The gains in equivalent sample sizes are between 56 and 135 percent for all outcomes other than BMI and more than doubled for 12 of the 19 outcomes. For BMI, the standardized innovation variance is very large, and so the gains in accuracy from the MKF are small, equivalent to increasing the current-year sample by just 7.2 percent. Current smoking, outpatient visits, and diabetes (with relatively large innovation variance) also have gains near the lower end of this range; stroke, kidney disease, and cancer (with relatively small innovation variance) show the greatest gains.

Table 3 summarizes the results of applying the MKF and the current-year mean to 10 of the 19 outcomes for AI/AN and Chinese samples of the NHIS; the full set of estimates, summarized below, are available online.

Table 3.

Comparison of Direct and MKF Estimates of Selected 2004 AI/AN and Chinese Health at Annual Effective Sample Sizes of 200

| AI/AN |

Chinese |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct 1-Year Estimate of 2004 |

1997–2004 MKF Estimate of 2004 |

Direct 1-Year Estimate of 2004 |

1997–2004 MKF Estimate of 2004 |

|||||||||

| Outcome | Estimate | Error Bands (1.96RMSE) | RRMSE | Estimate | Error Bands (1.96RMSE) | RRMSE | Estimate | Error Bands (1.96RMSE) | RRMSE | Estimate | Error Bands (1.96RMSE) | RRMSE |

| Prevalence estimates (%) | ||||||||||||

| Any heart disease | 14.2 | 4.8 | 17 | 14.2 | 3.2 | 11 | 3.7 | 2.6 | 36 | 3.7 | 1.7 | 24 |

| Cancer | 7.7 | 3.7 | 24 | 7.7 | 2.4 | 16 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 55 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 37 |

| Diabetes | 16.9 | 5.2 | 16 | 15.5 | 4.0 | 13 | 5.7 | 3.2 | 29 | 5.5 | 2.5 | 23 |

| Hypertension | 34.1 | 6.6 | 10 | 34.1 | 4.4 | 7 | 14.7 | 4.9 | 17 | 14.7 | 3.2 | 11 |

| Kidney disease | 3.8 | 2.6 | 36 | 3.8 | 1.7 | 23 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 100 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 66 |

| Smoke, current | 6.0 | 3.3 | 28 | 6.3 | 2.7 | 22 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 48 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 39 |

| Stroke | 3.8 | 2.6 | 36 | 3.8 | 1.7 | 23 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 48 | 2.1 | 1.3 | 32 |

| Means | ||||||||||||

| Mean inpatient days | 5.3 | 3.8 | 37% | 5.7 | 2.7 | 24% | 3.0 | 3.7 | 63% | 2.9 | 2.6 | 46% |

| Mean BMI | 28.4 | 1.6 | 3% | 28.6 | 1.5 | 3% | 23.2 | 1.6 | 4% | 23.4 | 1.5 | 3% |

| Mean outpatient visits | 0.8 | 0.1 | 6% | 0.8 | 0.1 | 5% | 0.7 | 0.1 | 7% | 0.7 | 0.1 | 6% |

Notes. A table of all the 19 outcomes is available in supplemental material SA4.

Bold text indicates RRMSE > 30%.Design effects from sample design were not considered.

Normal cell indicates 10% < RRMSE≤30%.

Underlined text indicates RRMSE≤10%.

AI/AN, American Indians/Alaska Natives; BMI, body mass index; MKF, modified Kalman filter; RMSE, root mean squared error; RRMSE, relative root mean squared error, analogous to relative standard error (RSE).

RRMSEs of Direct One-Year Estimates

Single-year RRMSEs achievable with annual effective sample sizes of 200 exceed 30 percent for 4 of the 19 estimates for AI/ANs and 11 of the 18 estimates for Chinese respondents.7 Four measures for AI/ANs and two for Chinese respondents had a single-year RRMSE<10 percent. Among dichotomous outcomes, higher prevalences generally result in lower RRMSEs. RRMSEs were generally lower for AI/AN (3–38 percent, median 22 percent) than for Chinese (4–100 percent, median 34 percent) because of the generally poorer health and higher prevalence estimates of AI/ANs.

RRMSEs of MKF Estimates

The MKF reduced the RRMSE of estimates for AI/ANs achievable with annual effective sample sizes of 200 by <1–13 percentage points (median reduction 6 percentage points of RRMSE) and reduced the RRMSE of estimates for the Chinese population by <1–34 percentage points (median reduction 10 percentage points of RRMSE). Improvements in RRMSE were greatest where single-year RRMSE were most in need of improvement: reductions in RRMSE were correlated with single-year RRMSE at r=0.96 and 0.98 across the 19 AI/AN and the 18 Chinese estimates, respectively. For AI/AN, this was sufficient to bring all estimates below 30 percent RRMSE and one additional estimate below 10 percent.8 For the Chinese population, four additional estimates were brought below 30 percent RRMSE.

When Does the MKF Change Simple Current-Year (2004) Point Estimates Substantially, in Addition to Improving Their Accuracy?

In most instances, the MKF reduces the MSE of the 2004 single-year estimate without substantially changing that point estimate. In these cases, the past data are consistent with the 2004 estimate, and so the MKF does not substantially alter the estimate but provides greater confidence in that estimate. The MKF alters the current-year point estimate only when (1) the past is informative and (2) the current year deviates substantially from its prediction from the past—the linear regression line. In such cases, the MKF proposes a compromise value between the direct (observed) current-year estimate and the prediction from the regression line based on past values, because there is evidence that the observed 2004 value deviates greatly from what would have been expected based on past variation around the regression line. The two largest differences between direct point estimates and MKF estimates are the AI/AN estimates for diabetes prevalence and mean inpatient days. In the case of diabetes, the MKF pulls the observed 2004 prevalence down from 16.9 to 15.5 percent because the 2004 value is much higher than expected, even accounting for the upward trend in diabetes. In the case of mean inpatient days, the mean of 5.3 observed in 2004 was much lower than expected, even given the downward trend, and so the MKF pulls the estimate upward.9

Key Parameters by Outcome

Here we describe, for 19 NHIS outcomes, the observed values of three key parameters that determine the accuracy of both direct and MKF estimates: the standardized root innovation variance (annual group-level variance component), the standardized slope over time, and the autocorrelation parameter.

Standardized Innovation Variance (τ2/σ2)

If the innovation variance is large, the current-year estimate is very unusual relative to the past, and combining current and past data results in large bias. In such a case, the MKF downweights the past, limiting the gains in precision no matter how many years are available. Thus, a large standardized innovation variance means that introducing data from another year swamps potential gains in precision. Specifically, in the absence of autocorrelation, the maximum possible increase in equivalent sample size from using the MKF rather than the current-year mean is bounded by σ2/(nτ2). Across the 19 NHIS outcomes, the median value of the standardized innovation variance is 6 × 10−4. Given the bound noted above, such a value allows much potential to increase accuracy at annual sample sizes near 200. The largest value is 387 × 10−4 for BMI, with the next largest values for smoking and outpatient visits. The precision of estimates for these three outcomes will improve relatively little with the MKF. The smallest ratios are <1 × 10−4 (stroke, followed by heart disease). The precision of these outcomes will improve substantially with the MKF.

Standardized Slope of the Time Trend (β/σ)

The median overall absolute value of the standardized slope is 53 × 10−4 (1/200), with the largest overall value observed for diabetes (156 × 10−4), followed by BMI and hypertension. The smallest overall absolute slope is for heart disease (4 × 10−4), followed by emphysema. Slopes were statistically significant (p<.05) for 10 of the 19 outcomes (hypertension, stroke, asthma, ulcer, cancer, diabetes, sinusitis, binge drinking, inpatients days, and workdays lost). The MKF estimators included linear trends even when they were estimated as nonsignificant (p>.05).

Autocorrelation Parameter (ρ)

The estimates of ρ have a mean of 0.32 (range 0.00–0.68) across the 19 outcomes. Autocorrelation is the highest for measures of health care utilization (inpatient and outpatient) and near zero for BMI, emphysema, diabetes, and smoking.

MKF Improvements in Direct One-Year Estimates

Under model assumptions the MKF can never worsen the MSE relative to current-year estimates alone. Across the entire parameter space (26,240 evaluations), the ratio of MSE for the MKF to direct current-year MSE ranged from 0.417 to 0.986. At the highest value (which occurred for n=1,000 observations per year and standardized innovation variance at the maximum value), the MKF applied to the 8,000 observations over 8 years has the same accuracy as a current-year mean of 1,000/0.986=1,014.20 observations, a very small gain over the current year alone. At the lowest value (which occurs at n=50 and the innovation variance equals zero), the MKF applied to 400 observations over 8 years has the same accuracy as a mean of 50/0.417=120 observations in the current year, more than doubling equivalent sample sizes. In fact, relMSE approaches this lower bound of 5/12 whenever the innovation variance approaches zero.10 For 10 percent of the design points used in the evaluation, the MSE of the MKF is between 41.7 and 44.4 percent of the current-year MSE. For 25 percent of the design points, the MSE of the MKF falls below 56.1 percent of the current-year MSE. The median relMSEs was 76.3 percent, so that MKF estimates correspond to at least 31 percent more equivalent sample size11 than the current-year sample for half of the parameter space.

In general, relMSE was insensitive to the values of the slope and varied very little across different values of ρ. As shown in Figure 1, relMSE was highly sensitive to both the effective sample size and the standardized innovation variance. The figure plots relMSE (averaged across values of ρ) as a function of the square root of the standardized innovation variance (τ/σ). At very low values of the root standardized innovation variance, relMSE nears its minimum, but it gains in accuracy from the MKF diminish with increasing root standardized innovation variance and annual sample size. The plotted “X” values in Figure 1 correspond to the 19 sets of parameter values for the examined NHIS outcomes at annual effective sample size of 200.

Figure 1.

Modified Kalman Filter (MKF) Mean Squared Error (MSE)/Current-Year MSE by Root-Standardized Innovation Variance (τ/σ) and Annual Sample Size, Averaging over Autocorrelation values

Note: “x” marks correspond to values for the 19 NHIS outcomes at an effective sample size of n=200 annual observations.

DISCUSSION

With limited survey budgets but pressing policy demands, the need for increased accuracy without adding to survey costs has never been greater. The MKF approach described here is a powerful method for meeting this need. Prevalence estimates are more accurate for all outcomes with this method, usually substantially so. For more than half of the 19 NHIS outcomes examined, the MKF produces immediate gains in precision equivalent to doubling the annual sample size for AI/AN and Chinese respondents, by incorporating information from the 7 prior years. Innovation variance was the primary determinant of the magnitude of gains, so that outcomes such as BMI with substantial innovation variance showed smaller gains than outcomes such as stroke, with very little innovation variance. While analytic changes alone may not achieve all measurement goals for very small racial/ethnic groups, they can make marked improvements at little cost and could substantially multiply the gains from even small increases in sample size for these groups.

There are several limitations to this approach. We necessarily assume a specific statistical model. While this is a parsimonious model that should reasonably approximate most health data, to the extent that the model does not hold, improvements in accuracy will be less than what is shown here. Sudden changes, such as those that might result from a dramatic policy change, would not fully benefit from an MKF approach in the first few years after such a change. The gains from the MKF over traditional current-year estimates would be very small at the sample sizes associated with larger groups such as non-Hispanic whites or even blacks in some surveys, and they might not merit the use of the MKF. Future research into methods for outcomes with little or no annual slope and outcomes with nonlinear trends could improve accuracy of the estimates.

The statistical advantages of the MKF estimator come with a price of increased complexity; the statistical model and computations for the MKF are complex and likely to be unfamiliar to policy makers. Nonetheless, the notion behind the MKF is simple: it combines data from multiple years, taking into account trends and autocorrelation, when the single-year sample is too small to provide estimates that are sufficiently accurate to support decision making.

What Can the MKF Contribute to Improving Health Estimates for Policy Makers?

By reducing error for small population groups, use of the MKF may bring additional point estimates within NCHS bounds of acceptable precision and thereby facilitate identification of disparities and assessment of when they have been eliminated. When standard errors (and RRMSEs) in traditional estimates are large, identifying disparities may be difficult because differences in point estimates among groups may not be statistically significant and reliable enough to guide policy. When traditional direct and MKF point estimates differ, one would know that either there is a large error in the current-year estimate or there was a true anomaly or rapid change in a health indicator for the subgroup this year, indicating caution in the interpretation of both estimates.

Because the MKF can substantially improve the accuracy of current-year prevalence estimates for small subgroups without increasing the data collection costs, the MKF can facilitate more efficient resource targeting. The MKF best takes advantage of sustained increases in sample size for low prevalence subgroups (such as the NHIS' recently implemented oversampling of Asians). The MKF gains less from large spikes in subgroup sample size that are not maintained, such as those that would result from “rotating oversamples.” Such designs provide increases in precision mainly for the 1 year of oversampling and the following 2 years only. Furthermore, for a given total sample size over a series of years, rotating oversample designs are inefficient for estimating slopes and innovations relative to even allocation of the sample across years, because estimates of change across time are most precise when estimates for all years are equally precise.

The MKF approach has potential to improve the estimation of outcomes for any small subgroup that is consistently identified over time in the NHIS or any other repeated cross-sectional survey. Consequently, incorporating the MKF approach to monitoring trends in health disparities across many groups into the set of existing approaches will better inform policy making and monitoring of efforts to reduce those disparities.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: This study was supported by contract 282-00-0005, task order 12 from the Office of Minority Health (HHS). Marc Elliott was supported in part by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC U48/DP000056). The authors would like to thank Kate Sommers-Dawes, Scott Stephenson, and Jacki Chou for assistance with the preparation of the manuscript.

Disclosures: None.

Disclaimers: The contents of the publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official views of the OMH or CDC.

NOTES

As measured by mean squared error (MSE).

Combines coronary heart disease, angina, myocardial infarction, and other heart disease.

The observed “states” in the Kalman filter framework.

If this assumption is violated, as it might be for outcomes like insurance that relate to socioeconomic status, then MKF estimates for some group means might not achieve the optimal accuracy, but they could still be substantially more accurate than alternative estimates. In such a case the potential gains in accuracy from using the MKF rather than the current-year sample mean might be somewhat overstated. Estimates of the MSE of the MKF estimates might also be biased. However, estimating separate values for these tuning parameters by groups could also degrade the accuracy of the MKF estimates and their MSE. Models that treat these variables (or transformations of them) for each group as draws from a common distribution and “shrink” them across groups as a compromise between a single value and separate estimates per group could lead to more accurate estimates than the simple MKF method proposed here.

Similarly, the RMSE is analogous to a standard error and is exactly the same as a standard error for simple 1-year estimates.

2001 standard errors for a series of dichotomous outcomes (uninsured under 65, self-rated health status of fair or poor, adult diabetes, adult flu shot, adult current smoker) for AI/AN and Chinese subgroups suggest that a typical NHIS design effect for these groups might be about 1.5, with the exception on uninsurance, which varies strongly by PSU, and hence has much larger design effects (2–5). This in turn suggests annual effective sample sizes of about 200/1.5=133 for these groups (based on analyses of the 2000–2002 National Health Interview person and sample adult-level data; J. Lucas, unpublished data, 2005).

There were no 2004 Chinese cases of emphysema in NHIS, reducing the health outcomes considered to 18.

As noted earlier, actual NHIS RRMSEs would be approximately 1.5 times as high as the values presented here, primarily as a function of design effects.

Large deviations could also indicate a nonlinear time trend, but a quadratic trend that predated 2004 or other similar misspecification would result in large estimates of innovation, which in turn would limit the adjustment. If the true functional form happens to change in the current year, this cannot be distinguished from a large chance deviation by any prospective method.

The lower bound is >1/8 because of estimation of the linear time trend.

Equivalent in MSE to a current-year sample size at least 131 percent as large.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Appendix SA2: Details of MKF Estimation, Prediction, and Fitting.

Appendix SA3: The MSE of Direct and MKF Estimators under the Statistical Model.

Appendix SA4: Comparison of Direct and MKF Estimates for all 19 2004 AI/AN and Chinese Annual Health Outcomes.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell is not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

REFERENCES

- Binder DA, Dick JP. Modeling and Estimation for Repeated Surveys. Survey Methodology. 1989;15(1):29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Blight BJN, Scott AJ. A Stochastic Model for Repeated Surveys. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society—Series B. 1973;35:61–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kalman R. A New Approach to Linear Filtering and Prediction Problems. Transactions of the ASME—Journal of Basic Engineering. 1960;82:35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Keppel K, Pamuk E, Lynch J, Carter-Pokras O, Kim I, Mays VM, Pearcy J, Schoenbach V, Weissman JS. Methodological Issues in Measuring Health Disparities. Vital and Health Statistics. 2005;2(141):1–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppel KG, Pearcy JN, Klein RJ. Measuring Progress in Healthy People 2010. Healthy People 2010 Statistical Notes. 2004;(25):1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kish L. Survey Sampling. John Wiley & Sons: New York; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lind JT. Repeated Surveys and the Kalman Filter. Econometrics Journal. 2005;8(3):418–27. [Google Scholar]

- Long SK, Graves JA, Zuckerman S. Assessing the Value of the NHIS for Studying Changes in State Coverage Policies: The Case of New York. Health Services Research. 2007;42(6, part 2):2332–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00767.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez-Luck C, Yu H, Meng Y-Y, Jhawar M, Wallace SP. Estimating Health Conditions for Small Areas: Asthma Symptom Prevalence for State Legislative Districts. Health Services Research. 2007;42(6, part 2):2389–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00793.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao JNK. Small Area Estimation. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. “National Health Interview Survey (NHIS)” [accessed on September 27, 2007]. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/nhis/hisdesc.htm. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Waksberg J, Levine D, Marker D. Assessment of Major Federal Data Sets for Analyses of Hispanic and Asian or Pacific Islander Subgroups of Native Americans: Inventory of Selected Existing Federal Databases. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.