Abstract

This qualitative study used sexual scripting theory to explore sexual stereotyping and sexual partnering practices among a racially diverse sample of men who use the Internet to engage in “bareback” sex with other men. The sample included 81 (73%) HIV-negative and 30 (27%) HIV-positive men who were recruited on Web sites where men seek other men to have bareback sex. Participants completed a semi-structured interview that included topics on their racial identification, their sexual experiences tied to race, and their experiences having sex with men of different racial groups. The findings suggested that a variety of race-based sexual stereotypes were used by participants. Sexual stereotyping appeared to directly and indirectly affect the sexual partnering decisions of participants. Sexual scripts may reinforce and facilitate race-based sexual stereotyping, and this behavior may structure sexual networks.

The Internet has emerged as a widely accessed environment in which men interact with other men for sexual purposes. A recently conducted meta-analysis of 15 studies examining use of the Internet among men who have sex with men (MSM) found that roughly 40% reported using the Internet to find sex partners (Liau, Millett, & Marks, 2006). Certain groups of MSM may be more likely to use the Internet to meet male sex partners. For example, men who deliberately seek to have condomless sex with other men (a practice also referred to as “bareback” sex) can use the Internet to facilitate such encounters (Carballo-Diéguez & Bauermeister, 2004; Carballo-Diéguez et al., 2006; Halkitis & Parsons, 2003; Halkitis, Parsons, & Wilton, 2003). Likewise, racial minority (i.e., Asian & Pacific Islander, Black, and Latino) men may constitute a large number of Internet-using MSM. Research suggests that racial minority MSM are more likely to be non-gay identified than White MSM (Kennamer, Honnold, Bradford, & Hendricks, 2000; Stokes, Vanable, & McKirnan, 1996) and report experiencing stigma and discomfort in traditional gay social venues (Beeker, Kraft, Peterson, & Stokes, 1998; Stokes & Peterson, 1998). Given these findings, the Internet may be a prime setting for racial minority MSM to meet sexual partners. There is evidence of the presence of racial minority MSM on the Internet, as race-specific chat rooms have been identified on Web sites that cater to men looking to “hook up” with other men (Carballo-Diéguez et al., 2006).

The Internet facilitates the process in which men meet other men who possess their preferred characteristics. This is largely because the Internet allows for selectivity in responding to advances from potential sex partners, and permits men to market themselves in a variety of ways to attract sex partners with their preferred characteristics. For many, race is a key factor that determines preferences for sexual partners (Ellingson & Schroeder, 2004). Race represents a socially constructed concept (Root, 2000), and using race to categorize individuals or predict behavior may be imprudent in some situations. However, as a social construction, race permeates social interactions between individuals and is a lens through which social actors view the world (Omi & Winant, 1986). As such, the expectations MSM have about sex partners of different racial groups and the role these expectations have on sexual partnering practices are important to consider, particularly in the context of the Internet. Nonetheless, perceptions that MSM have of potential sex partners within and outside of their own racial group, and the way these perceptions structure sexual partnering practices, have largely remained unexamined in social and behavioral research.

Sexual partnering is broadly defined as the process through which MSM initiate their sexual relationships, whether their expectation is for a long-term relationship or brief sexual encounter. Sexual partnering is considered a “local” process that is structured by the local organization of social life, the local population mix, and shared norms (Laumann, Gagnon, Michael, & Michaels, 1994). For example, the sexual partnering practices of men who use the Internet to meet sex partners in New York City will be impacted by the local norms of the gay community of that region.

The sexual partnering choices that MSM make may be related to the higher prevalence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), such as HIV, in different subgroups of this population—namely, racial minority MSM (Bingham, Marks, & Crepaz, 2003; Catania et al., 2001). Estimates of HIV risk behavior that have been obtained from diverse samples of MSM show no significant difference between racial minority and non-minority MSM (Mansergh et al., 2002; Millett, Peterson, Wolitski, & Stall, 2006; Peterson, Bakeman, & Stokes, 2001). Instead, potentially high-risk sexual networks that are structured by race have been posited as a better explanation for differences in HIV prevalence among minority and non-minority MSM (Berry, Raymond, & McFarland, 2007; Millett, Flores, Peterson, & Bakeman, 2007; Millett et al., 2006). This suggests that an exploration of the beliefs and sexual stereotypes that MSM hold about men of the same or different races may be important to consider in understanding the role that partnering behaviors have in structuring high-risk sexual networks.

Although researchers have documented race-based sexual stereotyping behavior among gay men (e.g., DeMarco, 1983; Díaz, 1998; Wilson & Yoshikawa, 2004), there has been little work aimed at defining sexual stereotypes. We draw on the work of Ashmore and Del Boca (1979, 1981) in conceptualizing and defining race-based sexual stereotypes. In this study, race-based sexual stereotypes are understood as inferred beliefs and expectations about the attributes a sexual experience will take on based on the race of the partner involved in the experience. These inferred beliefs and expectations are derived from common notions about characteristics of people from the same and different socially constructed racial group, as well as from personal experiences with persons within and outside the racial group in question (Ashmore, 1981; Ashmore & Del Boca, 1979). Race-based sexual stereotyping may emerge out of individual-level racism and prejudice; however, research has suggested that stereotypes and prejudice function relatively independently (Devine, 1989). Ashmore and Del Boca (1979) noted that it is important to distinguish sexual stereotypes from sexual stereotyping. The former refer to socio-cognitive structures that shape social behavior, and the latter refer to processes in which sexual stereotypes are used to ascribe sexually based attributes to a person based on their race. Thus, in the process of sexually stereotyping other MSM, men use and act on race-based sexual stereotypes they hold about men from the same and different racial groups.

Sexual scripting theory (Gagnon & Simon, 1973) provides a useful framework for examining race-based sexual stereotypes and understanding how sexual stereotyping shapes partnering practices. The theory posits that sexuality, like race, is socially constructed and that individuals develop and understand their sexuality in conjunction with powerful historical and cultural forces that shape social life (Gagnon & Simon, 1973; Parker & Gagnon, 1995). Similar to partnering behaviors, sexual scripts are locally derived and take on different forms and meanings according to the cultures and subcultures in which they are embedded (Laumann & Gagnon, 1995). According to the theory, sexual behavior is best understood as a function of cultural scripts (i.e., instructions for sexual conduct that are part of the cultural narratives and symbols that guide social behavior), interpersonal scripts (i.e., structured patterns of interaction influenced by shared norms within subcultures and groups), and intrapsychic scripts (i.e., plans and fantasies through which individuals think about their past, current, and future sexual behaviors). These scripts, individually and in tandem, inform and guide peoples’ sexual behaviors, preferences, and identities, and provide meaning to what may be considered appropriate sexual desires and activities (Gagnon & Simon, 1973; Laumann et al., 2004).

Sexual scripts may also underlie and perpetuate race-based sexual stereotypes. Like sexual partnering, sexual stereotypes are structured by race. These stereotypes exist as a function of intrapsychic, interpersonal, and cultural scripts. Sexual stereotypes are learned through processes of cultural socialization and translated, revised, or reinforced through patterns of interpersonal social and sexual activity and personal ideologies (Knapp-Whittier & Melendez, 2004; Simon, 1999). Thus, race-based sexual stereotyping reflects the personally, socially, and culturally based expectations MSM have about men within and outside of their racial group.

Within-racial group and between-racial group sexual stereotyping and sexual partnering practices remain largely unexamined among MSM, although the available research suggests that this represents an important area of inquiry with regard to HIV transmission among MSM—notably, those who engage in high HIV transmission risk behaviors. This qualitative study aimed to document the sexual stereotyping and sexual partnering practices of MSM who report engaging in bareback sex with partners met online. The specific questions that guided the study are as follows:

What are the sexual stereotypes that Asian and Pacific Islander, Black, Latino, and White MSM who engage in bareback sex have about sex partners from the same and different racial groups?

How does race-based sexual stereotyping affect the sexual partnering practices of these men?

Method

Sample

Between April 2005 and March 2006, MSM in the NYC area who were interested in bareback sex were recruited for a study called “Frontiers in Prevention.” Men were recruited on the six most popular free Internet Web sites used to meet men for bareback sex. (For a detailed description of the Web sites and the method used to identify them, see Carballo-Diéguez et al., 2006). Bareback Web sites were identified using a systematic method in which chat room users of a variety of MSM-themed Web sites were solicited for information about popular Web sites for men interested in bareback sex with other men. Using quota sampling methods, approximately equal numbers of self-labeled Asian, Black, Latino, and White participants were recruited using the six bareback Web sites identified.

Two active recruitment strategies were used to send advertisements about the study: instant messaging and e-mail to Web site users. A third, more passive, approach allowed users to contact study staff directly from a general information Web page describing our study. Study candidates were provided information about the study and, if interested, invited to call study staff for a brief screening. To qualify for the study, men had to (a) be at least 18 years old, (b) live in the NYC metropolitan area, (c) report using the Internet to meet men at least twice per month, (d) use at least one of the six Web sites selected for the study, (e) self-identify as a “barebacker” or as someone who practices bareback sex, and (f) have had bareback anal intercourse with a man met over the Internet. Individuals who qualified were scheduled for a face-to-face interview as close as possible to the date of the initial screening. This report is based on data collected from 120 men who completed a face-to-face interview.

Measures

After completing informed consent procedures, participants underwent an in-depth, face-to-face interview conducted by one of three clinical psychologists on our staff, as well as a structured assessment using a computer-assisted self-interview (CASI) program. The interviews lasted about two hr, and participants were compensated $50 in cash for their time. Data from the in-depth interviews are the focus of this study. The interviews covered a variety of topics including use of the Internet to meet male sex partners; sexual experiences; understandings, meanings, and experiences of barebacking; and concerns about HIV, STIs, and other health issues.

The data used in this study focus primarily on men’s sexual experiences tied to race (i.e., beliefs and perceptions about men from different racial groups, sexual experiences with men of the same and different racial groups, etc.). General questions about race and sexual partnering behaviors were asked and then followed up with probes. For example, participants were asked: “In terms of the U.S. way of categorizing race and ethnicity, how would you categorize yourself?” Probes included: “Do you include your race in your online profile?,” “Does including your race in your profile make a difference in the way men respond to your profile?,” and “What are some of these men’s expectations about you?” In exploring partnering practices and preferences for sex partners, men were asked this general question: “Tell me what it is like for you to meet men online for sex.” Follow-up probes included: “How do you select the men you intend to hook-up with?,” and “What characteristics do you look for?” Last, to examine partnering practices with men from the same or different racial groups, participants were asked: “Have you had sex with men of different races?” Follow-up probe questions included: “Are there any differences between men of different racial groups?,” and “Is the sex different with men from different races?” The questions used to derive data for this study represent roughly one-fifth of those asked in the full interview protocol.

Coding and Theme Construction

The interview recordings were transcribed, and transcriptions were reviewed for accuracy. Based on the structure of the interview guide used in the in-depth interviews, a preliminary codebook was created by a six-person team of researchers involved in the design and implementation of the larger study. The codebook consisted of major themes, with the topic of each section of the guide identified as a first level code (e.g., the interview guide topic “Ethnicity” was used to name the first level code “Ethnicity”), as well as definitions, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and examples for each code. Four transcripts were coded and compared to identify potential weaknesses in the codebook and examine concurrence (or lack thereof) in the coding process. The codebook was further specified, and new independent coding was conducted using NVivo, a software program designed for qualitative data analysis, by a team of four trained coders. Using kappa to assess interrater reliability, it was determined that the team reached 80% intercoder convergence across the 120 interviews.

After the initial coding of interview transcripts and construction of first level codes, we extracted text that was coded using the NVivo node for issues around race from the full interview transcripts. The primary text coded under this node came from the interview questions previously noted. Transcripts of the text excerpts were grouped by racial groups: Asian, Black, Latino, and White. Members of a team of five researchers each read through a different racial group’s text excerpts and independently developed codebooks based on observed themes. Three of the five team members were involved in the initial coding of full interview transcripts, and all team members read through several complete interviews prior to coding the race-specific text excerpts. Once initial codebooks were developed by each rater, they were compared and condensed into one standardized codebook. Using the standardized codebook, two members of the research team reviewed and coded the text excerpts for each racial group. The coding of text excerpts linked to each racial group were compared and discussed by the two coders until consensus was reached. The final, standardized codebook is presented in Table 1. The codebook was used to compare themes linked to sexual stereotypes and sexual partnering both within and between racial groups. Themes were integrated into a finding matrix, which was used as a framework to answer the research questions and condense the findings. Counts of the occurrences of themes within and across racial groups, as well as associations among themes, were examined using NVivo.

Table 1. Final Codebook Used for Coding Text Excerpts.

| Code | Definition | Sub-Codes |

|---|---|---|

| 1.0 Within-group sexual stereotypes | Beliefs or expectations about men within the participant’s racial group | 1.1 Sex characteristics 1.2 Gender expectations 1.3 Embodiment and body validation 1.4 Sexual positioning |

| 2.0 Between-group sexual stereotypes | Beliefs or expectations about men in other racial groups | 2.1 Sex characteristics 2.2 Gender expectations 2.3 Embodiment and body validation 2.4 Sexual positioning |

| 3.0 Sexual preference and partnering | Preferences for sex partners and partnering decisions according to race | 3.1 Self preferences 3.2 Other’s preferences |

| 4.0 Within-group differences around skin and hair color | Differences among men within specific racial groups (i.e., Black, Asian, White, Latino) with regard to skin color | None |

| 5.0 Differences in sex behavior | Differences in sexual activities and behaviors (i.e., types of sex, condom use, etc.) based on sex partner’s race | None |

Results

Sample Characteristics

A total of 120 MSM completed a face-to-face interview and CASI. The sample was comprised of 17 (14%) Asian men, 28 (23%) Black men, 31 (26%) Latino men, and 35 (29%) White men. It should be noted that race groups were created based on the way participants self-labeled and using the dominant terms that men used to describe themselves and other men. Men who identified themselves as Native American (n = 3; 3%) or “other” race or ethnicity (n = 6; 5%) were excluded from the sample because of the small sample size and the unique issues presented by these men (i.e., third-gender identity, issues of mixed identities). Thus, the final sample size for the study was 111. Characteristics of the study sample are presented in Table 2. The sample included 81 (73%) HIV-negative men and 30 (27%) HIV-positive men. There were no significant differences between HIV-negative and HIV-positive men with respect to race, education, and income. However, HIV-positive participants were significantly older than HIV-negative participants, t(118) = -2.82, p < .01.

Table 2. Demographic Characteristics of the Study Sample by HIV Status.

| Variable | HIV-Negative (n = 81) |

HIV-Positive (n = 30) |

Total |

t/χ2 4.63 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Racial group | |||||||

| Asian | 16 | 20 | 1 | 3 | 17 | 15 | |

| Black | 19 | 23 | 9 | 30 | 28 | 25 | |

| Latino | 22 | 27 | 9 | 30 | 31 | 28 | |

| White | 24 | 30 | 11 | 37 | 35 | 32 | |

| Age (M, SD) | 32.00 (9.87) | 38.00 (7.37) | 35.00 (9.56) | -2.82* | |||

| Education (M, SD) | 14.85 (3.19) | 14.60 (2.47) | 14.78 (3.00) | 0.39 | |||

| Annual income in thousands (M, SD) | 29.43 (24.61) | 20.29 (18.97) | 26.94 (23.48) | 1.84 | |||

Note. N = 111.

p ≤ .01.

What are the Sexual Stereotypes that MSM have about Men from Different Racial Groups

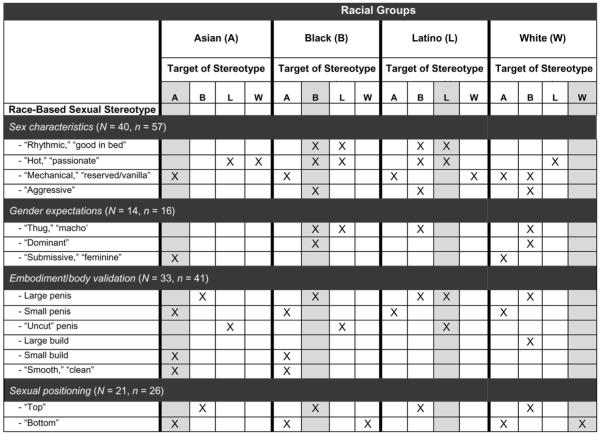

Four different categories of race-based sexual stereotypes emerged from the analysis of the interview data. Sexual stereotype categories were obtained through examining the ways in which participants stereotyped men within and outside of their racial group. As such, categories are noted as sub-codes to the codes for within-racial group and between-racial group sexual stereotypes (see Table 1) and include (a) sex characteristics, (b) gender expectations, (c) embodiment and body validation, and (d) sexual positioning. Within each category, sexual stereotypes are discussed from two perspectives. First, participants’ expectations about men from within their own racial group (i.e., within-group sexual stereotypes) are described. Second, between-racial group sexual stereotypes are examined by focusing on the beliefs men in each of the four racial groups have about men from other groups. Themes related to the content of within-group and between-group sexual stereotypes for each racial group are presented in a condensed format in Figure 1, which is referred to throughout the section. An “X” in the figure indicates that a theme was observed in at least three cases.

Figure 1.

Matrix of within-racial group and between-racial group sexual stereotypes and endorsements by racial group. Note. “X” indicates that theme was observed in at least three cases, as agreed on by coders; shaded columns refer to within-group sexual stereotypes; unshaded columns refer to between-group sexual stereotypes. N denotes the number of participants mentioning the stereotype at least once; n indicates number of times the theme was observed.

Sexual Stereotypes Based in Sex Characteristics

Sexual stereotypes about the overall characteristics of sexual behavior in which men of particular racial groups engage consist of beliefs about the features of the sexual act. These features include, but are not limited to, characterizations of sex as passionate, aggressive, or reserved and mundane. Overall, participants of different racial groups expressed variation in their expectations about the characteristics of sexual experiences they expected to have with men who were of the same or different race. Expectations appeared to be based in race-specific perceptions about the ways in which MSM from specific racial groups engage in sexual behavior with other men. Some men felt that stereotypes linked to sex types were positive or desirable, and enjoyed seeing the realization of these stereotypes in sexual interactions with same- and different-race men. Others expressed discomfort with the presumptions made about homogeneity in the features of sexual encounters with men from particular racial groups.

Within-group stereotypes

Although no major themes regarding within-group sexual stereotypes based in sex characteristics were observed among White participants, Asian, Black, and Latino men expressed similar beliefs regarding the type of sex they would experience with men who were of the same race. Generally, Black men characterized sex with other Black men as “rhythmic,” involving “more body movements,” “hot,” and “aggressive.” For example

Black [men are] hot. They’re willing to let it go ... they’re more intense. They’re more ... I don’t know ... they’re more intriguing like ... you know, and they know how to fuck. They know what they’re doing. They know how to do the damn thing, so to speak. (Black, 38, HIV-positive)

Many Black participants spoke of experiencing a deeper level of connection with partners who were also Black. In these situations, men were less likely to think they were being used as sexual objects (as was often the case when having White partners). For example, one Black participant noted that “having sex with Black men and Latino men ... is much more different than with White guys.” He explained the difference noting, “A lot of White guys ... are living out a fantasy of what they think sex with a Black man is going to be, like, instead of just enjoying sex” (45, HIV-negative).

Latino participants characterized sex with other Latino men similarly to the way Black participants described sex with other Black men. However, the ideas that sexual encounters were characterized by high levels of passion were more strongly tied to within-group sexual stereotypes among Latino men compared to others. One Latino participant noted: “So in the Latin people ... it’s the long sessions, and more hot. It’s like hot blood” (36, HIV-negative). These perceptions were considered positive by many Latino participants, and possibly facilitated the endorsement of the stereotype by Latino participants. However, some were uncomfortable with the characterizations. For example

Automatically, people just connect [being Latino] with being hot in bed ... who the hell wants to be labeled like that? I’m not happy with that. And a lot of times ... I’m afraid to say that I’m Latin, but it’s not because I’m ashamed of it, but it’s really because of that. (Latino, 39, HIV-positive)

Participants who were Asian frequently described sex among men within their racial group as “mechanical” or “reserved.” One participant noted: “Asians are too reserved and boring” (Asian, 31, HIV-negative). Another noted: “Maybe [with an Asian] person, like, I’d just like to have a quick suck, [but] I like something more intimate and more ... hot and passionate” (Asian, 36, HIV-negative).

Between-group stereotypes

As indicated in Figure 1, we observed that several of the stereotypes that participants held about men of their own racial group were also endorsed by men of other race groups. One striking example of this, seen across racial groups, is the notion that sex with Latino men was filled with passion and sensuality. For example, one participant suggested that White men “don’t come anywhere near the passion level of an African-American or a Latino man” (Black, 33, HIV-negative). An Asian participant who was asked if there are any differences between men of different racial groups when it comes to sex noted, “Yes, Latinos tend to be more sensual” (20, HIV-negative). The belief that Latino partners provide a sensual, passionate sexual experience was widely endorsed by White participants, whose comments included “Latins are often hot sexually” (58, HIV-positive), “[Latino men are] really passionate about the kissing” (38, HIV-negative), and “[Latino men have] great stamina and they [are] able to have sex again and again (32, HIV-positive).

Another sexual stereotype that was frequently endorsed across racial groups was that Asian MSM were sexually reserved. Black, White, and Latino participants characterized sex with Asian men similar to the way Asian men described sex with same-race partners: as “mechanical” or lacking passion, and as “vanilla” or less likely to involve certain sexual behaviors that may be considered risqué. One participant noted: “In general ... [Asian] men like especially ... are generally more vanilla, as it were, in their sexual, in their range of behavior” (White, 32, HIV-positive).

It is interesting to note that Latino participants described sex with Black men as “rhythmic,” “passionate,” and “aggressive,” which is identical to how Black participants perceived sex with other Black men. However, expectations that sex with Black men would be passionate and aggressive were not always seen as positive by Latino participants. For example, a Latino participant noted: “[Black men are] rough. There’s a certain type of roughness that they have, a certain type of just, raw.” He implied that this was not considered desirable at times, adding, “With the Black guys it’s just them being raw. And I’m used to them because I grew up around them, you know what I’m saying? But I just don’t necessarily want to be in bed with that” (25, HIV-negative). Similarly, some White participants viewed sex with Black MSM as aggressive. One described the experience as “so hot ... like [having] a voraciousness...[and] very animalistic quality [to it]” (White, 25, HIV-negative). However, other White participants perceived Black MSM as sexually conservative and reserved, which they related to issues around sexuality and discomfort in engaging in sexual behaviors with other men.

Sexual Stereotypes Based in Gender Expectations

Gender expectations represent the second broad category of race-based sexual stereotypes that emerged in our analysis. These stereotypes focused on common social constructions of the meanings and characteristics of what and who is considered to be masculine or feminine. Stereotypes of this kind were most often tied to Asian and Black MSM in both within-group and between-group findings.

Within-group stereotypes

Black participants frequently noted that they were stereotyped as hypermasculine (e.g., being a “thug” or “macho,” taking the dominant role in sexual activities). One participant, who noted a “thug factor” in perceptions of Black MSM, gave a broader description of his understanding of this phenomenon:

I (Interviewer): OK. Tell me a little about the thug factor here ... What is it? What does it mean?

R (Respondent): I think it just symbolizes, like, [a] dominant, aggressive, um, a man and people—sometimes they’ll put in the profile if they want a woman, you know, they put woman. So, they want that. They characterize a thug as somebody with big, baggy clothes, maybe their hair braided, and, um, you know, maybe they still live with their parents. (Black, 29, HIV-negative)

The thug image that Black participants attached to other Black MSM (and possibly themselves) is associated with hypermasculinity. Some participants suggested that the thug image may help to conceal homosexuality or combat the societal characterization of gay men as effeminate. One observed a connection between the thug stereotype and the ubiquitous “down low” phenomenon among Black MSM:

Well, when people talk about being on the down low, it’s just another way of saying, “What I do needs to be kept as discrete as possible.” Or, “I’m still in the closet, and I can’t, you know, jeopardize my career or my personal life or, you know, any of those things by having it come out that I deal with guys.” So it has to be as discrete as possible. And that’s what most of those, those, those thug male for male guys are after. (Black, 29, HIV-positive)

In contrast to Black participants, Asian participants perceived stereotypes about Asian men to be rooted in femininity and submissiveness. For example

Well, Asians are smaller and ... between the man and the woman, like the feminine side. In the gay world, the Asians, tend to be the submissive, passive—you know, feminine equivalent, I guess? (Asian, 31, HIV-negative)

Some Asian participants viewed themselves as submissive, whereas others believed the stereotype to be more a function of others perceptions’ of Asian men, with participants noting, “There’s this stereotype about an Asian pussy-boy or an Asian bottom-boy” (Asian, 31, HIV-negative), and “Most [White men] think that all Asians are submissive” (Asian, 25, HIV-negative).

Between-group stereotypes

Like within-group stereotypes, the targets of between-group sexual stereotypes based in gender expectations were primarily Black and Asian MSM, with the stereotypes depicting striking similarities across racial groups. White and Latino participants characterized Black MSM as generally taking on the hypermasculine (i.e., thug or macho) role and being dominant in sexual relationships, which is very similar to the views Black MSM had of themselves. One White participant noted that, “Black men tend to try to be more butch and straight” (37, HIV-positive), whereas another suggested that the Black MSM’s dominance in sexual encounters, notably those with White men, were part of a psychological “game” in which Black men reverse traditional power roles:

Well, you know, if [a Black man is] specifically looking for a White bottom—Well, now you go into a fetish round. ... Now you’ve got this little head game going where ... you’re going to be submissive. Well, it’s kind of like, you know, the whole reverse slave thing, I guess. ... So it’s a fetish. But so you’re into it with a more psychological thing going on than just a physical kind of thing. (White, 54, HIV-negative)

In contrast, Asian MSM were expected to be effeminate or submissive. These beliefs were primarily held by White MSM but also endorsed by Black and Latino participants. One White participant noted: “Asians and eastern cultures, they tend to get into more the femme side you know, in general” (37, HIV-positive). Likewise, participants reported expecting Asian MSM to be submissive in sexual encounters. One participant stated: “[Asians] do make great bottoms” (White, 29, HIV-negative). As is suggested by these statements, the belief that Asian and Black MSM take on strikingly different gendered characteristics during sex was pervasive among participants in the study.

Sexual Stereotypes Based in Embodiment and Body Validation

Beliefs about the physical attributes and body styles of men from different racial groups formed a great deal of the content of sexual stereotypes we observed. These beliefs, in general, suggested that different racial groups exhibit certain traits that other groups largely did not exhibit. As shown in Figure 1, sexual stereotypes based in embodiment and body validation included race-based beliefs about penis size, circumcision, and physical build.

Within-group stereotypes

One of the most prominent stereotypes held by participants in each of the racial groups was that Black MSM are expected to have large penises. This belief was widely endorsed by many Black men. For example, one participant noted: “[People looking at my online profile] always assume I have a big dick!” He added: “Like all the Black guys, you know, their dick size is like eight-and-a-half, pretty much, nine [inches]. Nine is even becoming like the standard size now” (Black, 29, HIV-negative). Other Black participants endorsed the idea that Black men generally have larger penises than men from other racial groups. However, some perceived the stereotype as emanating from White men and used in an exploitative way. Participants noted that White men “seem to associate Afro-Americans with large penises” (Black, 39, HIV-positive), and “I’ve met some White guys that clearly have the expectation of, you know, you’re a Black man, you got big dick” (Black, 45, HIV-negative).

Asian MSM noted that men of their racial group were distinguished by their small build and penis size and smooth skin. One participant explained: “Asians are bottoms, small cocks, you know. Submissive, you know” (Asian, 38, HIV-positive). Likewise, another noted: “A lot of guys who like Asian guys like them for being small, petite, thin, you know ... we have less, smaller sized dicks ... we’re primarily bottoms [and] we’re smooth everywhere” (Asian, 26, HIV-negative).

Latino men perceived other same-race men as having large, “uncut” penises. For example, one participant noted: “The myth of Hispanics and Blacks having large dicks is usually true” (Latino, 25, HIV-negative). Others spoke of the perception of Latino men as having uncircumcised penises and the changing perception of uncut as sexually appealing. For example, one participant explained: “Being uncut, years ago was like the biggest turn off. Now, all of a sudden, everybody wants that!” (Latino, 39, HIV-positive).

Between-group stereotypes

As shown in Figure 1, there was consistency across racial groups with regard to sexual stereotypes based in embodiment and body validation. For example, Black, Latino, and White participants all viewed Asian MSM similar to the way these participants viewed themselves—as having smaller physical features. Participants characterized Asian as having a “small build” (Black, 29, HIV-negative), “having smaller penises” (Latino, 21, HIV-negative), and being “very smooth ... they’re usually kind of slim and have decent bodies” (White 58, HIV-positive).

Likewise, Asian and Black participants, like Latino participants, viewed the uncircumcised penis as a prominent physical attribute of Latino men. However, Black and Asian men had varied feelings about Latino men being uncut. For example, one Black participant noted: “I find that with Latinos, I usually have a lot more oral sex, because a lot of Latino men ... are uncut and to me that’s a turn on” (43, HIV-negative). Other men also expected Latino men to be uncut, but did not look positively at this feature. Across racial groups, participants consistently endorsed the stereotype that Black MSM have large penises, with statements such as, “Black guys, most of them are very large” (White, 51, HIV-negative), and “Black men have big ones” (Latino, 25, HIV-negative). By far, this sexual stereotype was the one most frequently expressed in relation to Black men.

Sexual Stereotypes Based in Sexual Positioning

Stereotypes based in expectations about the sexual positions men from different racial groups take during sex represent the fourth and final category of race-based sexual stereotypes we observed. Sexual stereotypes of this type were most often tied to beliefs men had about the race of men who were more likely to take the insertive role (i.e., be a “top”) or the receptive role (i.e., be a “bottom”) in between-racial group sexual partnering.

Within-group stereotypes

Black men often reported viewing men of their racial group as primarily “tops,” and many men saw this as, in part, a function of the stereotypes suggesting that Black men have large penises and are more dominant and aggressive in sexual encounters. For example

The expectations, I think for Black guys there’s much more of an expectation in terms of sex and you know, being a top and being aggressive ... the expectation is much higher. (Black, 35, HIV-positive)

As with the thug stereotype, some participants suggested that Black men’s preferences for being the insertive partner during anal intercourse relates to cultural and personal issues about masculinity. For example, one Black participant stated: “I think [that] men of color have more hang-ups in regards to what it means to be a top or what it means to be a bottom” (29, HIV-negative).

In contrast to Black men, and consistent with stereotypes of submission and passivity, Asian participants perceived men from within their racial group to primarily be the receptive partner in anal intercourse. For example

[An Asian man is] a bottom, you’re—you know, you’re ... laying one leg back in bed, and you’re very passive. (Asian, 28, HIV-negative)

I guess like Asians come across as being predominately bottoms. And having a top or versatile Asian, I think [is] a rarity. (Asian, 36, HIV-negative)

Many White men suggested that their role in sexual intercourse varied based on the race of their sexual partner. Men noted that they expected to be the receptive partner in interactions with Black and Latino male partners, whereas they expected to be the insertive partner in sexual encounters involving an Asian partner.

Between-group stereotypes

Between-group stereotypes of sexual positioning were similar to those seen within the different racial groups (see Figure 1). Across racial groups, Black men were expected to be the insertive partner during intercourse, whereas Asian men were believed to be the receptive partner. For example

There [are] certain ... assumptions about what ethnic groups do, you know. Like Black guys only [take the insertive role] ... and Asian guys are always [the] bottom. (White, 58, HIV-positive)

I just know that Asians, most people think [that] Asians are bottom[s], and that Black [men are] mostly top[s]. (Asian, 28, HIV-negative)

It is interesting to note that Black participants frequently suggested that White men took the receptive role in sexual intercourse. However, this often was observed in relation to men’s expressions of feeling desired by potential White sex partners solely due to the pervasive stereotype that Black men are tops. For example, one participant noted that “White guys, if they’re interested in Black guys, they’re looking for a top” (Black, 39, HIV-negative).

Overall, several themes emerged in our analysis of the race-based sexual stereotypes held by MSM of different racial groups. Although there was some variation across groups, our findings demonstrate a great deal of consistency in the sexual stereotypes that Asian, Black, Latino, and White MSM use to understand themselves and other men, and in the expectations these men have with regard to sexual behaviors with same- and different-race sex partners.

How Does Race-Based Sexual Stereotyping Affect Sexual Partnering Practices

The previous section provided details regarding the content of sexual stereotypes held by participants. This section examines the function of sexual stereotypes among men who participated in the study, focusing on the way sexual stereotyping structures sexual partnering practices. The interview data suggest that sexual stereotyping had an important role in influencing how men decided with whom they do and do not engage in sexual relationships.

Sexual partnering and racial preferences

Many of the participants in the study gave clear preferences for sexual partners of particular racial groups. These preferences are summarized in Table 3, which provides information on participants’ stated preferences for sex partners of particular racial groups. The table shows the general patterns of attraction toward men of different races, although variability existed within each racial group. Nonetheless, there were clear themes regarding perceptions of the ideal sex partner’s race. For example, more than 30% of Black, Latino, and White participants considered Latino men to be desirable. Black and White participants frequently indicated that Latino men represented their preferred type of partner (with regard to race), along with men who were of their same race. Asian men most often preferred White men, who were also considered to be desirable, as at least one-fourth of men in each of the four racial groups reported preferring White men as sex partners.

Table 3.

Sex Partner Preferences by Racial Group

| Variable | Asian (n = 17) | Black (n = 28) | Latino (n = 31) | White (n = 35) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Preferred sex partner | ||||

| Asian | 2 (12) | 1 (4) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) |

| Black | 1 (6) | 9 (32) | 7 (23) | 4 (11) |

| Latino | 1 (6) | 10 (36) | 10 (32) | 14 (40) |

| White | 10 (59) | 7 (25) | 11 (35) | 9 (26) |

| No preference | 2 (12) | 4 (14) | 1 (3) | 5 (14) |

Note. N = 111. Percentages for each group will not total to 100%, as participants may have indicated having more than one preferred type of sex partner or may not have given a clear preference or lack of preference for any particular racial group.

On the other hand, Asian and Black men were generally considered the least sexually desirable among different-race men who were interviewed (see Table 3). It is interesting to note that few Asian men saw men from within their racial group as desirable, which is quite different from Black, Latino, and White participants, who consistently rated same-race men as being one of their most preferred types of sexual partners.

Although there were general themes regarding the most and least preferred races of sex partners, it should be noted that men of each of the four major racial groups were noted as sexually desirable by individual participants. Likewise, there were participants who indicated having no specific preference for sex partners of a particular racial group, and that they enjoyed the possibility of having sex with diverse men from within and outside their racial group. Although these men represented a minority of the participants in the study, they were represented in each of the four major racial groups.

Sexual partnering and color preferences

A striking theme that emerged in the analysis, and that was connected to sexual partnering, was the importance of the skin color as a way to distinguish one’s self from other men of the same racial group, and as a factor in determining attractiveness of potential sex partners. Although this finding was most pronounced among Black, Latino, and White men, participants in each of the four racial groups noted that skin color was a major factor involved in sexual attraction and partnering behaviors. Black and Latino men frequently indicated that men within their racial group (including themselves) characterized themselves in terms of skin color. For example

Some guys are real specific about wanting ... certain kinds of guys, for whatever reason. ... Even with among Black guys, I mean, complexion, dark or lighter or whatever. There’s all of that. ... [So] I list that I’m a lightskinned Black guy [in my online profile]. (Black, 44, HIV-positive)

I mean I prefer White and lighted skinned Hispanic male[s]. But sometimes if I’m really like feeling it or I’m desperate I would go with someone who is darker. (Latino, 21, HIV-negative)

The data suggested that although color played a role in determining perceptions of sexual attraction, there was not a generally agreed-on “better” color (i.e., lighter skinned vs. darker skinned) of potential sex partners. The relative meaning of lighter and darker skin tones appeared to differ according the racial group. For example, Black and Latino men often spoke of color preferences in terms of shades of brown, from very light to extremely dark. In contrast, Asian and White participants appeared to think of dark skin coloring in the traditional “tall, dark, and handsome” sense—as indicative of dark hair and eyes and olive skin tone. As such, these features were frequently tied to Mediterranean and Jewish men. For example, one participant noted: “I do like the dark complexions and strong features. I think that’s one of the things I like about Jewish men ... their strong, dark features” (White, 29, HIV-negative). At times, White participants (similar to Black and Latino participants) distinguished attractive racial minority men from non-attractive ones on the basis of skin color. For example, one participant noted: “I’m just not really turned on by [Black men]. I [could have sex with] a light-skinned Black, maybe” (White, 32, HIV-negative).

Although there did not appear to be a consistent theme with regard to whether lighter or darker skin was most preferred, the ideas that participants have about varying degrees of pigmentation may be shaped by race-based sexual stereotypes tied to darker men (i.e., those that are Black) and lighter men (i.e., those that are White). For example, Latino men with darker skin tones, such as Dominican men, were more likely to be perceived as aggressive and fitting the thug profile, similar to the way Black men were distinguished. Conversely, men with light skin tones may have been considered closer to the American standard of beauty, which may have made them more desirable to men across racial groups.

The influence of race-based sexual stereotypes on sexual partnering

The ways in which stereotyping shapes sexual partnering deserve special focus, as there were several themes that emerged in examining men’s race-based sexual stereotypes that were related to partnering behaviors. One of the most notable findings was the lack of within-group and between-group race-based sexual stereotypes tied to White MSM. The lack of negative stereotypes connected to this group of men may be a function of the use of non-minority (i.e., White) men as the standard by which other men are judged. This, in turn, may be tied to partnering behaviors of racial minority men who endorse this idea. Participants from different racial groups spoke of perceptions they had of White men as setting the standard in attractiveness. For example, participants noted that “White [men] definitely [have] the most beautiful features, facial features, facial structures” (Asian, 31, HIV-negative), and that White men have “porcelain skin [and are] so cute, so beautiful” (Latino, 41, HIV-positive). Another participant stated:

White people are just so superior [in] like, everything. Shows in movies, shows in everything—the media, propaganda, whatever. And Asian men just can’t compare to White guys. And that’s the bottom line ... it’s like you internalize it so much that we start to believe it, and therefore, we’re not that attractive anymore. (Asian, 18, HIV-negative)

The last quote presented exemplifies how the lack of stereotypes around White men, and the promotion and internalization of the belief that these men represent the standard of beauty, shape partnering practices and interactions between racial minority and non-minority men. As the quote suggests, this process may frequently take place in sexual interactions between Asian and White men. The following interview excerpts show how Asian men’s sexual stereotyping of other Asian men and White men affects their partnering choices:

With an Asian [guy], [there are] too many similarities and there’s no mysteriousness involved. (Asian, 28, HIV-negative)

Mostly it’s, like, White guys [that I’m interested in] ... they need someone who looks exactly like them. Same height, big, broad, muscle[s]. Now, I find that attractive, so that’s why I keep writing to those kind of guys, hoping that, you know, there are ... exceptions, exceptions, and they’d be [with] someone who is not like them. (Asian, 27, HIV-negative)

The perception of White men as a standard of physical and sexual attractiveness was not limited to Asian men. As previously noted, White men represented one of the more sexually desirable racial groups among men who were interviewed. The relative lack of negative stereotypes attached to White MSM may lead these men to believe that racial minority men are drawn to them. The following two interview excerpts serve as examples of this notion:

I’m not, as a rule, attracted to African-American men, I find many more wanting to hook up with me I think because I’ve started barebacking ... and I’m a bottom ... so I find that I have more Black men wanting me to hook up with them. (White, 45, HIV-positive)

R: I’m an Asian magnet.

I: An Asian magnet? Why do you think that is?

R: Because I have a masculine body and they don’t, Asian people don’t like other Asians. They don’t want to hook up with other Asians. (White, 31, HIV-negative)

The findings also suggest that sexual stereotyping of racial minority MSM can create situations in which these men can be sexually objectified and made to feel less like individuals. For example, the following participant’s statement regarding the frustration he feels in attempting to meet partners in online chat rooms shows how race-based sexual stereotyping affects sexual partnering through the reduction of the individual (and his personal characteristics) and the amplification of the stereotype into an unwarranted generalization:

[In] the Black [men] for White [men] or White [men] for Black [men] chat rooms, just the fact that I am Black, I will have half or nearly half of the White guys in the room message me under that assumption that I’m a top and that they want, you know, Black dick, when it says clearly in my profile that sexually I’m a bottom. They pay absolutely no attention to this. ... I could sit in that ... chat room for days ... and not get one message. But if I create a new screen-name that says “hot Black top” or, you know, “big-dick Black top” or anything that says “top” and “Black” in it, I’m getting messages ... it makes the dating scene kind of complicated for Black bottoms who are into interracial dating. (Black, 29, HIV-positive)

As the participant’s comment suggests, sexual partnering behaviors, at times, may be activated in response to a stereotype. In other words, for many of the men who participated in the study, it is through race-based sexual stereotyping that men of particular racial groups become desirable sexual partners. In the previous participant’s case, men responded to him only when he characterized himself as a “Black top.” Indeed, perceptions of Black men as tops represented a major way in which these men were considered sexually desirable. Notably, when this ideal was not realized, Black men lost their appeal to some participants. For example, one participant noted that “if [a Black man is] a bottom, I’m turned off” (Latino, 39, HIV-positive).

Sexual stereotypes based in beliefs that racial minority MSM are “exotic” or outside of the norm also influenced participants’ sexual partnering behaviors. For example, White participants described engaging in sexual activity with Black men or thug-type men as having novelty and excitement elements to it. For example

It depends on what you’re looking for at the time. Maybe you want a thug looking person or a thug type of person that just wants to have sex and doesn’t even want to talk to you. That to me is exciting because you’re thinking, what is he thinking? Is he liking this? Is he not? That’s exciting. You just get really excited about that kind of stuff. (White, 40, HIV-negative)

Sometimes it’s a taboo and exciting to [have sex] with somebody, like an African-American. ... That’s a little fantasy. Feels submissive. (White, 54, HIV-negative)

Finally, it should be noted that race-based sexual stereotyping was at times exploited by men belonging to racial groups that were the target of such stereotyping. For example, Black men, notably those who identified themselves as tops, spoke of using the belief that Black have large penises and are dominant in sexual encounters to their advantage in attracting other men. Several Latino participants also noted exploiting the pervasive stereotype that they are filled with sexual prowess and passion to entice potential sex partners. For example

I: And aside from, you know, the big dick stereotype, what other stereotypes do you hear?

R: Horny, good kisser, usually bisexual, for Dominicans ... aggressive.

I: What do you think about those stereotypes?

R: They’re stereotypes. I don’t really pay attention to stereotypes. I mean, most stereotypes are based on some kind of truths, but they are generalizations, so I don’t really pay attention to them. When I feel like it, I use it to my advantage. But it doesn’t really phase me. (Latino, 25, HIV-negative)

Taken together, these findings reveal that race-based sexual stereotyping and sexual partnering behaviors are strongly tied. This relation is one that was clearly perceived and sometimes exploited—to the advantage and disadvantage of the men who desired them—by men in the study. Sexual stereotyping both hindered and promoted men’s abilities to find desired sex partners, often depending on whether the participant felt he fit the mold the stereotype suggested. Moreover, these stereotypes, by virtue of their prominence and level of endorsement among men in the study, shaped men’s ideas about what is and is not sexually attractive. Thus, the findings suggest that sexual stereotyping had a strong influence on the sexual partnering behaviors of the men in the sample.

Discussion

The research presented in this article represents some of the first work conducted with the aim of understanding race-based sexual stereotypes and describing how race-based sexual stereotyping affects the sexual partnering decisions of MSM. The findings emerged out of interviews with a racially diverse sample of men who engage in bareback sex with other men. The sample provides a unique context through which researchers can explore these findings in relation to broader populations of gay men, and to U.S. society as a whole. The race-based sexual stereotypes we observed in this study stem from these broader populations and the cultural and structural forces that they comprise. Likewise, it is within these broader groups that the influence of sexual stereotyping on sexual partnering behaviors must be understood.

One important finding is the co-occurrence of several of the categories of race-based sexual stereotypes that emerged in the analysis. The sexual stereotypes tied to gender expectations, embodiment and body validation, and sexual positioning were strongly interconnected for Asian and Black participants. Nonetheless, each category of race-based sexual stereotype operated in a distinct way for participants, who were varied in viewing individual dimensions of sexual stereotypes as positive (e.g., the large penis size of Black men, the smooth skin of Asian men) and negative (e.g., aggressiveness among Black men, femininity among Asian men). The findings speak to the dynamic ways in which the four categories of race-based sexual stereotypes operate and are expressed in the sexual lives of the men interviewed.

The way the categories of sexual stereotypes that emerged in the analysis grouped together by racial group may make sense conceptually when thinking of these stereotypes within the broader socio-historical context of American culture. Cultural studies in the historical, anthropological, and sociological literatures have documented how native and immigrant racial minority men and women have been sexually exploited within U.S. society (Collins, 2004; Nagel, 2003; Smith, 1998) and collectively suggest that America has and continues to distinguish and stereotype individuals from different racial groups in sexual terms. Studies specifically examining MSM have documented race- and gender-based characterizations that men make of themselves and other MSM within and outside of their racial groups. For example, researchers have examined how Latino immigrant gay men have been viewed as hypersexual within the gay community, and often feel objectified by White gay men (Díaz, 1997). Similarly, research by Wilson and Yoshikawa (2004) and Stokes and Peterson (1998) documented the exoticization of Asian gay men and Black gay men, respectively, within mainstream gay settings, such as bars and other social venues. In this work, racial minority gay men have been described as feeling like objects of sexual desire (or alternatively, objects of sexual loathing) on solely the basis of their race. The findings presented here correspond to extant research and theory, and strongly suggest that perceptions of sexuality are organized and structured according to race, among other factors, within the gay community and in U.S. society as a whole.

The findings presented here also reinforce the utility of sexual scripting theory (Gagnon & Simon, 1973) as a way to organize and understand sexual stereotyping and sexual partnering behaviors, and as a framework through which we can appreciate how sexual stereotypes are linked to cultural representations within broader society (Ashmore, 1981). The four major categories of race-based sexual stereotypes we observed, and the role sexual stereotyping has in influencing sexual partnering decisions among MSM, can be thought of as functions of the three levels of scripts referred to in sexual scripting theory. The types of sexual stereotypes that our participants endorsed were clearly linked to larger cultural lenses through which Asian, Black, Latino, and White persons generally view each other. Research has suggested that cultural sexual scripts play an important role in deeming what is and is not considered attractive among gay men (Connell & Dowsett, 1993; Knapp-Whittier & Melendez, 2004; Knapp-Whittier & Simon, 2001). Similarly, the race-based sexual stereotypes we observed represented interpersonal scripts, as many of the men in the sample felt that stereotypes were validated in day-to-day social and sexual interactions that they and other MSM had with men from the same and different races. Finally, the sexual stereotypes that participants spoke of are, in part, determined by intrapsychic scripts. These scripts represent the personal experiences, fantasies, and desires that participants had with (or about) other people within and outside of their racial groups throughout their social and sexual development. In this sense, culture does not solely dictate the content of race-based sexual stereotypes among MSM; rather, it is the context in which personal experiences and beliefs about same- and other-race men are understood and managed. Like the stereotypes that emerged in our analysis, the levels of scripts (i.e., cultural, interpersonal, and intrapsychic) through which the sexual stereotypes can be explored must be considered dynamic and interrelated. These scripts, and race-based sexual stereotypes that emerge out of them, represent ways in which personal agency and sociocultural and historical constraints shape sexual meanings and sexual partnering behaviors among MSM (Knapp-Whittier & Melendez, 2004; Mutchler, 2000).

Our findings support the notion that race-based sexual stereotypes may be transformed in such a way that stereotyped features, and preferences for these features in certain groups of MSM, change depending on current trends. For example, several of the Latino men in the sample noted that in previous times they felt that having an uncircumcised penis was considered unattractive by men from different racial groups. However, the same men reported feeling that, currently, being uncircumcised is a “draw” and a way to attract men from outside their racial group. Although this example provides evidence that some race-based sexual stereotypes may change over time, our findings also provided strong support for the stability of sexual stereotypes. Sexual stereotypes about men from different racial groups persisted despite evidence that may have proven them invalid. The persistence of these race-based sexual stereotypes may, in part, be due to the context in which men in our sample met each other—via the Internet. The Internet represents a context in which gay men can present themselves in a variety of ways that may or may not be accurate. In essence, men can have a real self and a “cyber self.” However, meeting men over the Internet also allows for the sexual stereotypes that people use to understand and differentiate others to be exploited. Given that there is no physical interaction, the sexual scripts and stereotypes that men use to understand sexuality across racial groups are relied on more heavily as men meet and partner with each other via the Internet. Thus, the Internet may be involved in the amplification and reinforcement of race-based sexual stereotypes that exist about certain groups of MSM.

Another notable finding was linked to skin color distinctions and the relation of skin color to sexual stereotyping and sexual partnering. Given the reinforcement of sexual stereotypes via the Internet, it should not be that surprising that many of the racial minority men who participated in the study (notably, Black and Latino participants) distinguished themselves in terms of skin color. Also, White men acknowledged color as a distinguishing factor among potential partners by differentiating non-minority and racial minority men according to their skin and hair color. Distinguishing one’s self from others within the same racial groups according to skin color may represent one technique in which racial minority MSM break the mold that race-based sexual stereotypes promote and allow themselves to be looked at through a (possibly more attractive) lens used to examine non-minority men. For example, by describing themselves as “light-skinned” to potential partners, Black and Latino men may have been looked at as closer to White. Indeed, Black and Latino men who were lighter skinned were considered attractive by many White men who otherwise were not attracted to Blacks or Latinos. Similar to the findings obtained in this study, research conducted specifically with Latino gay men has shown that many of these men think of MSM with darker skin tones as more aggressive, less likely to take on the receptive role in anal sex, and more likely to have a large penis compared to Latino men with lighter skin tones (Carballo-Diéguez et al., 2004). This gives credence to the idea that darker color is associated with sexual stereotypes tied to Black men. Thus, preferences for color may align themselves with preferences for stereotyped characteristics linked to men in particular racial groups. Both can be considered a function of both personal experiences and broader historical and cultural forces that have for centuries promoted White features as the standard of beauty.

A final, highly salient finding from the study is the use of White MSM as representing the norm to which racial minority MSM compare themselves. In this study, the lack of findings with regard to (a) within-group, race-based sexual stereotypes observed by White MSM and (b) between-group, race-based sexual stereotypes about White MSM endorsed by racial minority men may be linked to the use of White MSM as a standard to which other groups of MSM are compared among men in the sample. Thus, the lack of race-based sexual stereotypes for White men makes sense conceptually—there were not as many stereotypes linked to these men because, as members of the dominant culture, they form the reference group, and men from other racial groups are measured by the standard within the dominant culture. In other words, race-based sexual stereotyping represents the predominant way through which White MSM distinguish themselves from racial minority MSM and racial minority rate themselves against normative White attributes. The key is understanding who is the reference group, and why. The “why” involves an exploration of how gender roles and conventional ideas around appropriate masculinity and sexuality are understood, reinforced, or suppressed among MSM (Dowsett, 2003). Although this exploration is outside the scope of the work presented in this article, it serves to help to provide a framework through which we can begin to explore how power and privilege shape the content of race-based sexual stereotypes, and the use of these stereotypes in making sexual partnering decisions.

Before concluding, it is important to note the implications of these findings to our understanding of HIV transmission and prevention. As previously noted, sexual partnering choices that MSM make may be related to higher HIV prevalence among racial minority MSM (Berry at al., 2007; Bingham et al., 2003; Catania et al., 2001), as estimates of sexual risk behavior have been found to be relatively the same across racial groups (Mansergh et al., 2002; Peterson et al., 2001). Our findings suggest that race-based sexual stereotypes may function to segregate sexual networks and, in doing so, may create risk groups that are based less on behavior and more on racial categorizations. Race-based sexual stereotypes may also make the targets of these stereotypes more likely to engage in potentially risky sexual behaviors, particularly with the perpetrator of the stereotype. For example, Wilson and Yoshikawa (2004) found that Asian gay men who experienced discrimination within the gay community, based on stereotypes of East Asian men as passive and feminine, were more likely to report engaging in sexually risky behavior. Many of these men reported a lack of self-efficacy to use condoms in situations where they could be stereotyped by potential sex partners. These findings, taken together with those from this study, suggest that to fully understand the role of race-based sexual stereotypes in perpetuating HIV risk, it is important to understand both the social structures that these stereotypes potentially serve to buttress (i.e., sexual networks structured by race), as well as the individual-level behaviors that they may reinforce (i.e., unprotected sex).

The findings from this study must be examined and interpreted within limits. Although we believe our findings have broad social underpinnings that can be found in examinations of sexual stereotyping and sexual partnering in other populations, the findings here cannot be generalized to all MSM. Although our sample was racially diverse, it included only men who engage in bareback sex and is not representative of MSM as a whole. Another limitation is the race of interviewers who interviewed participants. Interviewers and participants were not matched in terms of race, and this may have affected the types of responses participants gave to sometimes racially charged questions. However, every effort was made to establish positive rapport and to ensure comfort in each interview. Finally, although the findings suggest a strong relation between race-based sexual stereotyping and partnering behaviors, the directionality of the relation cannot be ascertained using these data. Thus, we cannot report definitive evidence as to whether sexual stereotyping affects partnering decisions, or collective partnering decisions among MSM within particular racial groups affects sexual stereotyping behavior.

Despite the limitations of the study, we believe the findings presented here to be extremely important to defining race-based sexual stereotypes among MSM and understanding how sexual stereotyping affects sexual partnering behaviors, particularly within the context of the Internet. It is clear that race-based sexual stereotypes influence MSMs’ ideas about how men within and outside of their racial group function sexually. Likewise, sexual stereotyping allows MSM to create expectations about potential sex partners that have enormous consequences for men’s abilities to meet other men and turn their desires for men with certain characteristics into realities in sexual partnering.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant No. R01 MH69333 from the National Institute of Mental Health to the HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies at New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University (Principal Investigator: Alex Carballo-Diéguez). We gratefully acknowledge Gary Dowsett and Robert Remien for their invaluable comments on earlier drafts of this article.

References

- Ashmore RD. Sex stereotypes and implicit personality theory. In: Hamilton DL, editor. Cognitive processes in stereotyping and intergroup behavior. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1981. pp. 36–81. [Google Scholar]

- Ashmore RD, Del Boca FK. Sex stereotypes and implicit personality theory: Toward a cognitive-social psychological conceptualization. Sex Roles. 1979;5:219–248. [Google Scholar]

- Ashmore RD, Del Boca FK. Conceptual approaches to stereotypes and stereotyping. In: Hamilton DL, editor. Cognitive processes in stereotyping and intergroup behavior. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1981. pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Beeker C, Kraft JM, Peterson JL, Stokes JP. Influences on sexual risk behavior in young African-American men who have sex with men. Journal of the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association. 1998;2:59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Berry M, Raymond HF, McFarland W. Same race and older partner selection may explain higher HIV prevalence among Black men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2007;21:2349–2350. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f12f41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham CR, Marks G, Crepaz N. Attributions about one’s HIV infection and unsafe sex in seropositive men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2003;5:283–289. [Google Scholar]

- Carballo-Diéguez A, Bauermeister J. “Barebacking”: Intentional condomless anal sex in HIV-risk contexts. Reasons for and against it. Journal of Homosexuality. 2004;47:1–16. doi: 10.1300/J082v47n01_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carballo-Diéguez A, Dolezal C, Nieves L, Diaz F, Decena C, Balan I. Looking for a tall, dark, macho man ... sexual-role behaviour variations in Latino gay and bisexual men. Culture Health & Sexuality. 2004;6:159–171. [Google Scholar]

- Carballo-Diéguez A, Dowsett GW, Ventuneac A, Remien RH, Balan I, Dolezal C, et al. Cybercartography of popular internet sites used by New York City men who have sex with men interested in bareback sex. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2006;18:475–489. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.6.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania JA, Osmond D, Stall RD, Pollack L, Paul JP, Blower S, Binson D, et al. The continuing HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:907–914. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH. Black sexual politics. Routledge; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW, Dowsett GW. The unclean motion of the generative parts: Frameworks in Western thought on sexuality. In: Connell RW, Dowsett GW, editors. Rethinking sex: Social theory and sexuality research. Temple University Press; Philadelphia: 1993. pp. 49–75. [Google Scholar]

- DeMarco J. Gay racism. In: Smith MJ, editor. Black men/White men: A gay anthology. Gay Sunshine Press; San Francisco: 1983. pp. 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Devine PG. Stereotypes and prejudice: Their automatic and controlled components. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1989;56:5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz RM. Latino gay men and the psychocultural barriers to AIDS prevention. In: Levine MP, Nardi PM, Gagnon JH, editors. In changing times: Gay men and lesbians encounter HIV/AIDS. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1997. pp. 221–244. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz RM. Latino gay men and HIV: Culture, sexuality and risk behavior. Routledge & Kegan Paul; Boston: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dowsett GW. Some considerations on sexuality and gender in the context of HIV/AIDS. Reproductive Health Matters. 2003;11:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(03)02290-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellingson S, Schroeder K. Race and the construction of same-sex markets in four Chicago neighborhoods. In: Laumann EO, Ellingson S, Mahay J, Paik A, Youm Y, editors. The sexual organization of the city. Chicago University Press; Chicago: 2004. pp. 93–122. [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon JH, Simon W. Sexual conduct: The social sources of human sexuality. Aldine; Chicago: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Parsons JT. Intentional unsafe sex (barebacking) among HIV-positive gay men who seek sexual partners on the Internet. AIDS Care. 2003;15:367–378. doi: 10.1080/0954012031000105423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Parsons JT, Wilton L. Barebacking among gay and bisexual men in New York City: Explanations for the emergence of intentional unsafe behavior. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2003;32:351–357. doi: 10.1023/a:1024095016181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennamer JD, Honnold J, Bradford J, Hendricks M. Differences in disclosure of sexuality among African American and White gay/bisexual men: Implications for HIV/AIDS prevention. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2000;12:519–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp-Whittier DK, Melendez R. Intersubjectivity in the intrapsychic sexual scripting of gay men. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2004;6:131–143. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp-Whittier DK, Simon W. The fuzzy matrix of “my type” in intrapsychic sexual scripting. Sexualities. 2001;4:139–165. [Google Scholar]

- Laumann EO, Ellingson S, Mahay J, Paik A, Youm Y. The sexual organization of of the city. Chicago University Press; Chicago: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Laumann EO, Gagnon JH. A sociological perspective on sexual action. In: Parker RG, Gagnon JH, editors. Conceiving sexuality: Approaches to sex research in a post modern world. Routledge; New York: 1995. pp. 183–213. [Google Scholar]

- Laumann EO, Gagnon JH, Michael RT, Michaels S. The social organization of sexuality: Sexual practices in the United States. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Liau A, Millett G, Marks G. Meta-analytic examination of online sex-seeking and sexual risk behavior among men who have sex with men. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2006;33:576–584. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000204710.35332.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansergh G, Marks G, Colfax GN, Guzman R, Rader M, Buchbinder S. “Barebacking” in a diverse sample of men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2002;16:653–659. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200203080-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millett GA, Flores SA, Peterson JL, Bakeman R. Explaining disparities in HIV infection among Black and White men who have sex with men: A meta-analysis of HIV risk behaviors. AIDS. 2007;21:2083–2091. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282e9a64b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millett GA, Peterson JL, Wolitski RJ, Stall R. Greater risk for HIV infection of Black men who have sex with men: A critical literature review. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1007–1019. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutchler MG. Making space for safer sex. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2000;12:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel J. Race, ethnicity, and sexuality: Intimate intersections, forbidden frontiers. Oxford University Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Omi M, Winant H. Racial formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1990s. Routledge; New York: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Parker R, Gagnon JH. Conceiving sexuality: Approaches to sex research in a postmodern world. Routledge; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JL, Bakeman R, Stokes J. Racial/ethnic differences in HIV risk behavior among young men who have sex with men. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Medical Association. 2001;5:155–162. [Google Scholar]

- Root M. How we divide the world. Philosophy of Science. 2000;67:S628–S639. [Google Scholar]

- Simon W. Sexual conduct in retrospective perspective. Sexualities. 1999;2:126–133. [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. Sex and sexuality in early America. New York University Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes JP, Peterson JL. Homophobia, self-esteem, and risk for HIV among African American men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1998;10:278–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes JP, Vanable PA, McKirnan DJ. Ethnic differences in sexual behavior, condom use, and psychosocial variables among Black and White men who have sex with men. Journal of Sex Research. 1996;33:373–381. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson PA, Yoshikawa H. Experiences of and responses to social discrimination among Asian and Pacific Islander gay men: Their relationship to HIV risk. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2004;16:68–83. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.1.68.27724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]