Abstract

Cancers often overexpress EGF and other growth factors to promote cell replication and migration. Previous work has not produced targeted drug carriers sensitive to abnormal amounts of growth factors. This work demonstrates that liposomes bearing EGF receptors covalently crosslinked to p-toluic acid or methyl-PEO4-NHS ester (or, in short, MRBLs) exhibit an increased rate of release of encapsulated drug compounds when EGF is present in solution. Furthermore, the modified EGF receptors retain the abilities to form dimers in the presence of EGF and bind specifically to EGF. These results demonstrate that MRBLs are sensitive to EGF in solution and indicate that MRBL-reconstituted modified EGF receptors, in the presence of EGF in solution, form dimers which increase MRBL permeability to encapsulated compounds.

Introduction

Cell replication is a fundamental process that maintains the human body in working order. Although this process is closely regulated under normal conditions, sometimes cells with deleterious genetic mutations may evade these checkpoints and replicate (rather than undergo apoptosis). If these cells and their daughter cells are not detected by the immune system, they may continue to replicate and accrue further deleterious mutations, a process that may, given time, lead to cancer [1]. Cancers often overexpress growth factors such as EGF to facilitate cell replication and migration [2].

Cancers that produce abnormal amounts of EGF, known as epidermal growth factor (EGF)-overexpressing cancers, have, along with other types of cancers, drawn enormous expense for treatment [1], [3], [4], [5]. Such treatment generally involves surgery, radiation therapy, or generalized chemotherapy, or some combination thereof. All of these treatment methods are attendant with significant systemic risks and side effects, and repeat treatments are often necessary [1], [6], [7]. Research toward developing better cancer therapies is of critical importance.

A newer approach for treating EGF-overexpressing cancers involves EGF receptor inhibitors (EGFRIs). Although EGFRIs represent an improvement over generalized chemotherapy in terms of efficacy and specificity, they often need to be used along with another treatment method (such as radiation therapy) and, further, are still attendant with potentially significant skin, hair, nail, and mucosal side effects [8], [9], [10].

The use of a targeted drug carrier (e.g., a liposome) to release chemotherapeutic drugs specifically in the neighborhood of EGF-overexpressing tumors has the potential to achieve the treatment ideality of maximal efficacy and maximal specificity [11]. Existing targeted drug carriers are generally triggered by factors such as ultrasound [12], [13]. To use these drug carriers in vivo, ultrasound waves (or other triggering factor) are aimed at tumors' precise locations so that drugs are only released from the carriers when they are at those locations [12], [13]. However, particularly for metastatic tumors, it is not always possible to identify the tumors' precise locations [1]. Without this information, it is not possible to achieve targeted drug delivery with these carriers. Hence, an ideal targeted drug carrier for EGF-overexpressing tumors would be one sensitive to abnormal amounts of EGF (i.e., an EGF-triggered carrier).

Here it is demonstrated in vitro that liposomes bearing EGF receptors crosslinked to p-toluic acid or methyl-PEO4-NHS ester (or, in short, MRBLs) are sensitive to EGF in solution.

Results

MRBLs are sensitive to EGF

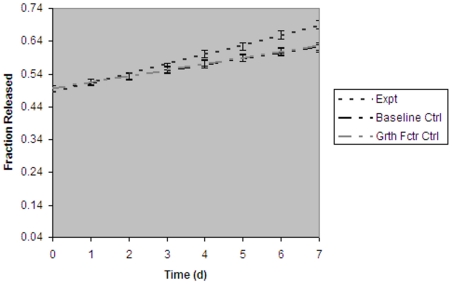

Assessment of in vitro actinomycin D release from MRBLs demonstrated that the presence of EGF in solution resulted in an increased rate of actinomycin D release (Figure 1).

Figure 1. EGF in solution increases rate of encapsulated actinomycin D release.

Percentage (expressed as fraction released) of encapsulated actinomycin D released as assessed by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Baseline Ctrl, actinomycin D-encapsulating MRBLs without growth factor added to solution. Grth Fctr Ctrl, actinomycin D-encapsulating MRBLs with VEGF added to solution. Expt, actinomycin D-encapsulating MRBLs with EGF added to solution.

EGF can induce dimerization of modified EGF receptors

It was next sought to verify whether EGF could induce dimerization of the modified EGF receptors. Modified EGF receptors and unmodified EGF receptors were assessed with and without the presence of EGF. In the presence of EGF, modified and unmodified EGF receptors formed dimers; in the absence of EGF, only receptor monomers were detected (Figure 2).

Figure 2. EGF induces dimerization of modified EGF receptors.

SDS-PAGE analysis of EGFR dimerization. EGFR+EGF Lane, unmodified EGF receptors with EGF present. EGFR Lane, unmodified EGF receptors without EGF present. mod. EGFR + EGF Lane, modified EGF receptors with EGF present. mod. EGFR Lane, modified EGF receptors without EGF present. EGF Lane, only EGF present (no EGF receptors present).

MRBL-borne modified EGF receptors show specificity for EGF

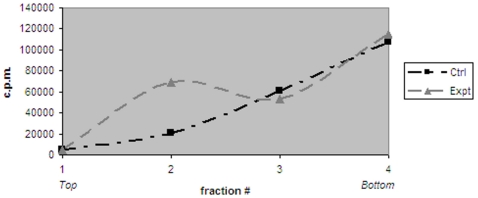

To assess whether MRBL-borne modified EGF receptors retain specificity for EGF, binding of radiolabeled [125I]EGF to reconstituted receptors was assessed with and without pre-incubation of the MRBLs with an excess of unlabeled EGF. [125I]EGF binding was observed only in the absence of unlabeled EGF pre-incubation (Figure 3).

Figure 3. MRBL-borne modified EGF receptors show binding specificity for EGF.

Binding of [125I]EGF to MRBLs as assessed by liquid scintillation counting. Ctrl, MRBLs pre-incubated with an excess of unlabeled EGF before incubation with [125I]EGF. Expt, MRBLs not pre-incubated with an excess of unlabeled EGF before incubation with [125I]EGF.

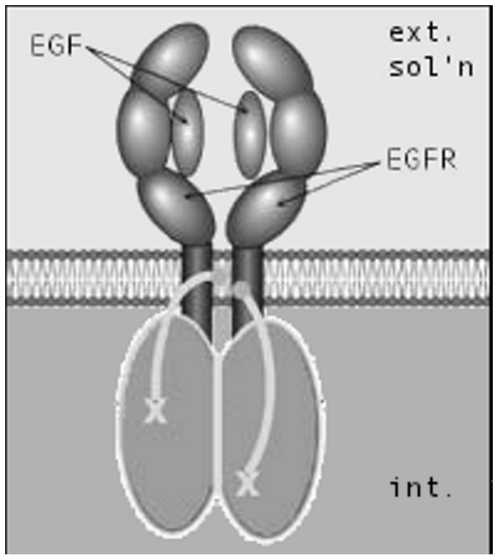

Modified EGF receptor dimers affect MRBL permeability to encapsulated drug

To identify the components underlying the EGF sensitivity of MRBLs, it was noted that modified EGF receptors retain specificity for EGF; modified EGF receptors form dimers in the presence of EGF; and MRBLs bearing these receptors exhibit sensitivity to EGF in solution. These results indicated that, in the presence of EGF, MRBL-borne modified EGF receptors form dimers which increase the MRBL permeability to encapsulated compounds (Figure 4).

Figure 4. MRBL-borne modified EGF receptor dimers interact with the MRBL lipid bilayer to increase MRBL permeability (schematic).

Dimerization of MRBL-borne modified EGF receptors. ext. sol'n, exterior solution. EGFR, modified EGF receptors. int., interior of unilamellar MRBL. X-----, crosslinked p-toluic acid or methyl-PEO4-NHS ester.

Discussion

This work demonstrates that the transmembrane incorporation of EGF receptors covalently crosslinked to p-toluic acid or methyl-PEO4-NHS ester in MRBLs makes these MRBLs sensitive to EGF in solution. Specifically, when drug compounds are encapsulated in these MRBLs, a higher rate of in vitro drug release from these MRBLs is observed when EGF is present (versus when EGF is not present) in solution. EGF receptors modified with the crosslinking procedure described herein retain the ability to form dimers in the presence of EGF. In addition, when these modified EGF receptors are reconstituted in MRBLs, the MRBLs demonstrate the ability to bind EGF specifically.

The results imply that modified EGF receptors reconstituted in MRBLs bind to EGF (if present) in the solution and (if EGF is present in the solution) form dimers which increase MRBL permeability to encapsulated compounds. Further work may be performed to elucidate the precise mechanism whereby MRBL-reconstituted modified EGF receptor dimers increase the MRBL permeability.

Methods

Methods summary

Covalent crosslinking procedures have been described previously [14], [15]. For the preparation and collection of MRBLs, lipid film hydration of egg phosphatidylcholine followed by dialysis and sucrose gradient centrifugation was used. The dimerization capability of modified EGF receptors was assayed by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis as described previously [23]. Reconstituted receptor binding specificity was evaluated using radiolabeled [125I]EGF as described [16]. For assessment of drug release from MRBLs, 1H NMR spectroscopy (400 MHz, CDCl3) was used to evaluate the increase in amount of released drug in a sample over time [24], [25], [26].

Modification of receptors

Methyl-PEO4-NHS ester (an NHS-activated polyethylene oxide compound) (Pierce) was added at a molar ratio of 1∶1 to epidermal growth factor receptor in 50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.02% Triton X-100, 2 mM DTT, 50% glycerol, pH 7.5 (Invitrogen), and the solution was thoroughly mixed. Separately, p-toluic acid (Alfa Aesar) was added at a molar ratio of 1∶1 and crosslinked to (unmodified) EGF receptor in 50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.02% Triton X-100, 2 mM DTT, 50% glycerol, pH 7.5 by using EDC and NHS (Pierce) [14], [15]. The two separate solutions were mixed to obtain a single modified EGF receptor solution.

Preparation of liposomes

Egg phosphatidylcholine (98%; Lipoid) was dissolved in chloroform in a polypropylene tube. Chloroform was evaporated with a stream of nitrogen, leaving a thin lipid film, which was redried under a stream of nitrogen to remove residual traces of solvent [16], [17], [18], [19], [20]. The lipid film was rehydrated in Tris-buffered saline (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) containing 50 mM octyl-β-glucoside (Pierce) and thoroughly mixed by vortexing. The solution was dialyzed for 36 h against three changes of buffer (Tris-buffered saline, 30 mM benzamidine (Calbiochem), 0.1 mM PMSF (Pierce)) to remove the detergent, allowing liposomes to form. The resulting turbid solution was mixed with sucrose to 40% (w/v) and applied at the bottom of a sucrose gradient (0.5 mL 40% sucrose, 1.5 mL 20% sucrose, 1.5 mL 5% sucrose), then centrifuged at 40,000 g for 3 h to remove residual traces of detergent. Fractions were collected from the top of the gradient. Liposomes were freshly prepared for each experiment [16], [17].

Preparation of drug-encapsulating liposomes

Drug-encapsulating liposomes were generated by the addition of actinomycin D (EMD Biosciences) to the rehydrated lipid-containing Tris-buffered saline solution prior to vortexing [17].

Preparation of MRBLs

Modified epidermal growth factor receptor-bearing liposomes (MRBLs) were generated by the addition of modified EGF receptor in 50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.02% Triton X-100, 2 mM DTT, 50% glycerol, pH 7.5 to the rehydrated lipid-containing Tris-buffered saline solution prior to vortexing [16], [18].

Dimerization assays for free modified EGFR

Analysis of modified EGF receptor dimerization capability was performed using SDS-PAGE with Coomassie blue staining, exactly as described [21], [22], [23].

Binding assays for MRBL-borne modified EGFR

Analysis of modified EGF receptor ligand-binding capability was performed using radiolabeled [125I]EGF (PerkinElmer), exactly as described [16].

Drug release assays

In vitro release experiments were carried out at an incubation temperature of 298 K by phase separating free drug (i.e., unencapsulated drug) and drug-encapsulating MRBLs (i.e., encapsulated drug) in a sample at various time points and removing small aliquots from the free drug phase of the sample. The change in concentration of unencapsulated drug in the sample over time was determined using 1H NMR spectroscopy (400 MHz, CDCl3) [24], [25], [26].

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Yasunori Hayashi, David Housman, and Robert Langer for discussions, Gerald Feigenson for technical advice on NMR spectroscopy, Jonathan King for assistance with centrifugation, and Qiaobing Xu for suggestions regarding polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The author has declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: This work was supported by funding from the MIT Office of the Provost and the MIT Portugal Program. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Kumar V, Fausto N, Abbas A. St. Louis, MO: Saunders; 2004. Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease, 7th ed. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel TB, Bertics PJ. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2006. Epidermal growth factor: methods and protocols. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gansauge F, Gansauge S, Schmidt E, Muller J, Beger HG. Prognostic significance of molecular alterations in human pancreatic carcinoma - an immunohistological study. Langenbeck's Arch Sur. 1998;383:152–155. doi: 10.1007/pl00008076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poch B, Gansauge F, Schwarz A, Seufferlein T, Schnelldorfer T, et al. Epidermal growth factor induces cyclin D1 in human pancreatic carcinoma: evidence for a cyclin D1-dependent cell cycle progression. Pancreas. 2001;23:280–287. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200110000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnum PV. Cytotoxic drug market will influence growth of high-potency active ingredients. Pharm Tech EPT 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeAngelis LM, Seiferheld W, Schold SC, Fisher B, Schultz CJ. Combination chemotherapy and radiotherapy for primary central nervous system lymphoma: radiation therapy oncology group study 93-10. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4643–4648. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forastiere AA, Goepfert H, Maor M, Pajak TF, Weber R, et al. Concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy for organ preservation in advanced laryngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2091–2098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robert C, Soria JC, Chosidow O. Folliculitis and perionyxis associated with the EGFR inhibitor erlotinib. Targeted Oncol. 2006;1:100–103. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agero ALC, Dusza SW, Benvenuto-Andrade C, Busam KJ, Myskowski P, et al. Dermatologic side effects associated with the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:657–670. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galimont-Collen AFS, Vos LE, Lavrijsen APM, Ouwerkerk J, Gelderblom H. Classification and management of skin, hair, nail and mucosal side-effects of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:845–851. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mouritsen OG. Berlin, De: Springer; 2005. Life-as a matter of fat: the emerging science of lipidomics. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerasimov OV, Boomer JA, Qualls MM, Thompson DH. Cytosolic drug delivery using pH- and light-sensitive liposomes. Adv Drug Del Rev. 1999;38:317–338. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(99)00035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dromi S, Frenkel V, Luk A, Traughber B, Angstadt M, et al. Pulsed-high intensity focused ultrasound and low temperature-sensitive liposomes for enhanced targeted drug delivery and antitumor effect. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2722–2727. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeSilva NS. Interactions of surfactant protein D with fatty acids. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;29:757–770. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0186OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grabarek Z, Gergely J. Zero-length crosslinking procedure with the use of active esters. Anal Biochem. 1990;185:131–135. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90267-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Panayotou GN, Magee AI, Geisow MJ. Reconstitution of the epidermal growth factor receptor in artificial lipid bilayers. FEBS Lett. 1985;183:321–325. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mimms LT, Zampighi G, Nozaki Y, Tanford C, Reynolds JA. Phospholipid vesicle formation and transmembrane protein incorporation using octyl glucoside. Biochemistry. 1981;20:833–840. doi: 10.1021/bi00507a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ge G, Wu J, Lin Q. Effect of membrane fluidity on tyrosine kinase activity of reconstituted epidermal growth factor receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;282:511–514. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tuthill TJ, Bubeck D, Rowlands DJ, Hogle JM. Characterization of early steps in the poliovirus infection process: receptor-decorated liposomes induce conversion of the virus to membrane-anchored entry-intermediate particles. J Virol. 2006;80:172–180. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.1.172-180.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schneider WJ. Reconstitution of the low density lipoprotein receptor. J Cell Biochem. 1983;23:95–106. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240230110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lemmon MA, Bu Z, Ladbury JE, Zhou M, Pinchasi D, et al. Two EGF molecules contribute additively to stabilization of the EGFR dimer. EMBO J. 1997;16:281–294. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.2.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schlessinger J. Ligand-induced, receptor-mediated dimerization and activation of EGF receptor. Cell. 2002;110:669–672. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00966-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lax I, Mitra AK, Ravera C, Hurwitz DR, Rubinstein M, et al. Epidermal growth factor (EGF) induces oligomerization of soluble, extracellular, ligand-binding domain of EGF receptor. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:13828–13833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maurer N, Wong KF, Hope MJ, Cullis PR. Anomalous solubility behavior of the antibiotic ciprofloxacin encapsulated in liposomes: a 1H-NMR study. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1374:9–20. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(98)00125-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Juretschke HP, Lapidot A. Actinomycin D, 1H NMR studies on intramolecular interactions and on the planarity of the chromophore. Eur J Biochem. 1984;143:651–658. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feigenson GW. California Institute of Technology, : Pasadena, CA; 1974. Nuclear magnetic relaxation studies of lecithin bilayers. [Google Scholar]