Abstract

The cellular transformation of a precursor mRNA (pre-mRNA) into its mature or functional form proceeds by way of a splicing reaction, in which the exons are ligated to form the mature linear RNA and the introns are excised as branched or lariat RNAs. We have prepared a series of branched compounds (bRNA and bDNA), and studied the effects of such molecules on the efficiency of mammalian pre-mRNA splicing in vitro. Y-shaped RNAs containing an unnatural l-2′-deoxycytidine unit (L-dC) at the 3′ termini are highly stabilized against exonuclease hydrolysis in HeLa nuclear extracts, and are potent inhibitors of the splicing pathway. A bRNA containing internal 2′-O-methyl ribopyrimidine units and L-dC at the 3′ ends was at least twice as potent as the most potent of the bRNAs containing no 2′ modifications, with an IC50 of ∼5 µM. Inhibitory activity was maintained in a branched molecule containing an arabino-adenosine branchpoint which, unlike the native bRNAs, resisted cleavage by the lariat- debranching enzyme. The data obtained suggest that binding and sequestering of a branch recognition factor by the branched nucleic acids is an early event, which occurs prior to the first chemical step of splicing. Probably, an early recognition element preferentially binds to the synthetic branched molecules over the native pre-mRNA. As such, synthetic bRNAs may prove to be invaluable tools for the purification and identification of the putative branchpoint recognition factor.

INTRODUCTION

A vital step in the biosynthesis of mRNA is the removal of non-coding introns from precursor mRNAs (pre-mRNA; Fig. 1) (1,2). This post-transcriptional event, termed RNA splicing, is a highly dynamic process involving an intricate plethora of RNA–RNA, RNA–protein and protein–protein interactions for correct sequence alignment and sequential transesterification reactions to occur (3–6). The snRNAs, especially U2 and U6, are intimately associated with the reactive regions of the intronic segment during the chemical steps of splicing, supporting the hypothesis that the splicing reactions are RNA catalyzed (7–11). Furthermore, construction of the catalytically active spliceosome (12) complex is heavily dependent on the activity of numerous protein factors, of which more than 70–100 have been identified to date (13). Many of these protein factors are homologous to both the lower eukaryotic yeast and the mammalian splicing systems. Likewise, the majority of the trans-acting factors involved in the splicing pathway are also highly conserved and present throughout the eukaryotic kingdom. While the signals for RNA splicing are more divergent in humans than in lower eukaryotes, the chemistry of the splicing reaction remains evolutionarily conserved.

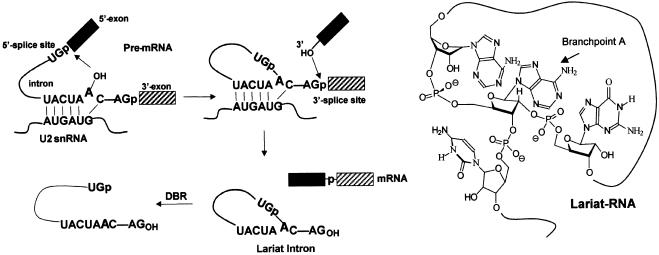

Figure 1.

RNA splicing and debranching, and structure of lariat RNA.

In the first step, the 2′-OH group of a conserved adenosine residue is activated to attack the phosphodiester bond at the 5′ splice site, resulting in the release of the 5′ exon and formation of an unusual intron RNA lariat (Fig. 1) (14–16). The second transesterification reaction involves the ligation of the two exons and excision of the intron lariat. The 2′,5′-phosphodiester bond of excised lariats is subsequently hydrolyzed in vivo by the lariat debranching enzyme (DBR), an activity that was first identified in 1985 (17) and later demonstrated to be the rate-determining step during intron degradation (Fig. 1). In yeast, the branchpoint sequence (BPS) UACUAAC (A = branchpoint adenosine) is highly conserved, whereas in mammalian systems, less sequence stringency is observed with YURAC (Y = pyrimidines; R = purine) as the BPS; however, the yeast sequence remains optimal in both systems (18–20).

Even though substantial research efforts have been directed towards complete elucidation of the splicing process and the synergistic relationship between the multitude of factors involved, the overall process remains yet to be defined precisely. It is recognized that the U2 and U6 snRNAs restrain the 5′ splice site and branch region in an accurate spatial arrangement for the first step of splicing to occur (21–27). In both the yeast and mammalian systems, the pre-mRNA BPS is recognized several times during the splicing process. First, the BPS is recognized by a single-stranded RNA-binding protein referred to as the branchpoint-binding protein (BBP) in yeast or SF1 (i.e. mBBP) in mammals (28,29). BBP appears to be involved only in early recognition since it is present only during initial spliceosomal assembly events (30). Subse quently, the U2-snRNP binds to the BPS in part by base-pairing interactions between the U2 snRNA and the nucleotides flanking the branchpoint adenosine unit (24–26). Rather than being completely base paired to the U2 snRNA, the branchpoint adenosine residue is speculated to be unpaired and ‘bulged’ out of the duplex region, thereby making it available for ensuing interactions that will position it for nucleophilic attack at the 5′ splice site (Fig. 1) (31,32). In addition, as the spliceosome repositions itself to reach the correct conformation for catalysis, other protein factors have been shown to interact with the BPS via site-specific cross-linking interactions with the pre-branched adenosine (33,34). Allegedly, one of these factors, p14, may play a role in positioning the adenosine moiety for attack at the 5′ splice site junction (35).

Our group has had a long-standing interest in the synthesis and characterization of branched RNAs (bRNAs) (36–40). These unusual RNA molecules are important from a structural perspective and as model systems for studying RNA splicing and debranching. Of specific interest to our group is the biological role of lariat RNA, and its interactions with spliceosomal components after the first step of the splicing reaction (i.e. lariat–3′-exon recognition). Given that synthetic linear oligonucleotide constructs have proven expedient for the study of pre-mRNA splicing (41–43), it seemed wise and worthwhile to investigate branchpoint recognition events by trans-acting spliceosomal factors using synthetic branched nucleic acids (bNAs) in their native splicing system. Preliminary investigations conducted by our group have shown that bNAs were capable of inhibiting pre-mRNA splicing in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, suggesting that bNAs were selectively sequestering a branch recognition factor possibly involved in branch selection after step I (44). We inferred from this that one or more elements in the spliceosome can recognize the exogenous bNAs, which now compete with the lariat–3′-exon intermediate, thereby inhibiting the second transesterification reaction. Although promising inhibitory profiles were obtained with bRNA molecules, the natural constituents of the bRNAs (i.e. ribose sugar), especially at the 3′ termini of the molecule, made them excellent substrates for the ubiquitous cellular nucleases. In effect, a thorough study was not possible given this limitation. Furthermore, consistency in terms of batch-to-batch activity of the yeast extracts for in vitro assays was difficult to reproduce and required much optimization (45). Alternatively, human extracts have allowed for much dissection of purified splicing complexes and components, and published protocols for their preparation typically yield reproducibly active extracts (46–48).

Here we describe our efforts to stabilize the bRNAs against omnipresent endonuclease and debranching activity in mammalian splicing extracts. In addition, we examine the merit of the ribose sugar, bRNA base sequence and stereochemistry of the branchpoint nucleotide on bNA recognition during pre-mRNA splicing using HeLa nuclear extracts. These studies have allowed us to define, for the first time, the characteristics of the branched nucleotide that are recognized by mammalian spliceosomal elements.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Branched oligonucleotides were synthesized on an ABI 381A DNA synthesizer via our well-established convergent solid-phase bNA synthetic methodology on 500 Å controlled pore glass solid support (1 µmol scale synthesis) (38,40). In the case of compounds 14 and 15, the arabino-adenosine (ara-A) bis-phosphoramidite was prepared in an identical fashion to the ribo-adenosine bis-phosphoramidite as previously described (36). The coupling conditions and times during solid-phase synthesis were identical to those employed for bRNA synthesis (40). The linear, V-shaped and Y-shaped constructs were purified by either denaturing PAGE or anion-exchange HPLC, and the extraneous salts were removed prior to biological testing (40). The nucleotide composition of the individual samples was confirmed by negative-mode MALDI-TOF-MS (49,50) and/or comparison with oligonucleotide standards of similar sequence constitution and length. HeLa nuclear extracts were generously donated by Dr Andrew MacMillan (University of Alberta) and Dr Benoit Chabot (University of Sherbrooke) and were used as received. All extracts were prepared according to the method of Dignam and contained a final concentration of 100 mM KCl (51). Extract was stored at –80°C and thawed on ice prior to use.

HeLa nuclear extract oligonucleotide stability assays

The nuclease stability profiles of select linear and branched oligonucleotides were conducted in the presence of HeLa nuclear extract under pre-mRNA splicing conditions (i.e. 25% extract) (52). Substrate RNAs were radioactively labeled at their 5′-hydroxyl termini (5′-32P) prior to incubation with [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase according to the supplier’s directions (Fermentas). Degradation assays were accomplished in a 5 µl total volume and consisted of 15–50 × 103 c.p.m. of 5′-end-labeled linear or branched oligonucleotides, 25% (v/v) HeLa extract, 2 mM MgCl2, 60 mM KCl (final concentration), RNase inhibitor (30 U), yeast phenylalanine tRNA (30 µg), 1 mM ATP and 5 mM creatine phosphate. The reactions were also supplemented with 10 mM KH2PO4 as a general phosphatase inhibitor in order to prevent loss of the 5′ radioactive label. The samples were incubated at 30°C for 15–90 min, and extracted with phenol/chloroform. Samples were partitioned on a 16% denaturing gel (7 M urea) and visualized by autoradiography. The amount of intact RNA was quantified using the UN-SCAN-IT software program (Silk Scientific) and the individual lanes normalized with respect to the reaction lacking any nuclear extract (t = 0).

PCR amplification of the PIP85.B splicing substrate gene

DNA plasmid containing the 234 nucleotide PIP85.B splicing gene was obtained from Dr Andrew Macmillan (University of Alberta) (31,53). It contains a single adenosine in the branch region and a polypyrimidine tract (see Supplementary Material S1, available at NAR Online). PCR amplification of the gene was conducted on a Minicycler™ programmable thermal controller (M.J. Research Inc., USA). The sequences of the PCR primers used were (i) M13F, 5′-d(CGC CAG GGT TTT CCC AGT CAC GAC)-3′; and (ii) CQ27, 5′-d(AGC TTG CAT GCA GAG ACC)-3′. The reaction was conducted in a total volume of 100 µl in a mini PCR tube containing: plasmid DNA (2.4 µg), primers M13F and CQ27 (2 µM each), 400 µM of dNTPs (equimolar mixture of dATP, dGTP, dCTP and dTTP), 10× Taq polymerase buffer (10 µl), Taq polymerase enzyme (10 U) and the remaining volume made up with sterile water. Amplification was conducted for 30 cycles using an annealing temperature of 45°C for 30 s and a 90 s elongation time at 72°C. The dsDNA was purified from the reaction mixture by standard phenol/chloroform extraction. The aqueous layer (diluted to 0.5 ml with sterile water) was applied to a NAP-5® desalting column and eluted with sterile water (1 ml). The eluent was concentrated in vacuo and the amplified DNA analyzed on a 2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide (20 ng/ml) alongside a 1 kb DNA ladder (1 µg), and visualized and photographed on a UV transilluminator (see Supplementary Material S2).

Run-off transcription of the PIP85.B splicing gene

The 234 nt RNA transcript was synthesized from the PCR-amplified DNA template using T7 RNA polymerase. Reactions were conducted in 25 µl volumes and consisted of: 5 µl of 5× T7 RNA polymerase buffer [200 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.9, 30 mM MgCl2, 50 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 50 mM NaCl and 10 mM spermidine], 100 mM DTT (2.5 µl), 10 mM solution of ATP, GTP and CTP (1.25 µl), 200 µM UTP (1.88 µl), RNase inhibitor (0.5 µl, 40 U/µl), [α-32P]UTP (2.5 µl, 50 µCi, 800 Ci/mmol), DNA template (1 µl), T7 RNA polymerase (1 µl, 20 U/µl) and sterile water to 25 µl. The transcription reaction was incubated at 37°C for 4 h and cooled at –20°C overnight or on dry ice for 1 h in order to inactivate the enzyme. The transcript was purified either by denaturing PAGE (8%, 7 M urea, 19:1 cross-linking) or using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s specifications.

In vitro pre-mRNA splicing reactions in HeLa extracts

Splicing of the pre-mRNA transcript was conducted under standard conditions with slight modifications in 5–10 µl reaction volumes (52). Characteristically, reactions consisted of 25% (v/v) HeLa nuclear extract (containing 100 mM KCl), 2 mM MgCl2, 60 mM KCl (final concentration), 1 mM ATP, 5 mM creatine phosphate, 0.4 U/ml RNase inhibitor, 50–100 × 103 c.p.m. of internally radiolabeled transcript and the remaining volume was made up with sterile water. In the case of competitive inhibition assays, the reactions were supplemented with synthetic linear and branched oligonucleotides at concentrations ranging between 100 nM and 20 µM. This was conducted by pre-mixing the hot, radiolabeled pre-mRNA with cold oligonucleotide inhibitor. Samples were left on ice and the reactions initiated by the addition of the nuclear extract followed by heating to 30°C. Splicing reactions were incubated at 30°C for 30 min in order to resolve the pre-mRNA, mRNA, lariat–3′-exon and lariat intermediates. The protein content of the reactions was digested by the addition of 6 µl of a mixture containing proteinase K (7.4 µg/ml final), PK stop buffer (2.6% SDS, 110 mM Tris, pH 8 and 110 mM EDTA), and yeast phenylalanine tRNA (1 µg/ml), and heated at 55–60°C for 30 min. The reactions were quenched with 40 µl of sodium acetate (3 M) and the volume brought up to 400 µl with sterile water. Individual reactions were extracted once with 200 µl of PCI (25:24:1, phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol) and once with 200 µl of chloroform followed by precipitation with 2.5 vols of ice-cold absolute ethanol. The RNA was pelleted by centrifugation, the supernatant ethanol discarded and the pellet washed once with 50 µl of ice-cold ethanol. The RNA was quantitated on a Bio-Scan QC-2000 Benchtop Radioactivity Counter. Samples were dissolved in gel loading dye (2000 c.p.m./µl) and partitioned on 15% acrylamide:bis-acrylamide (19:1) containing 8 M urea. Gels were initially run at 500 V for 30 min in order to remove any residual salts from the samples, and then run at constant power (75 W) for 3.5–4 h. Gels were autoradiographed as described previously (16–24 h, –20°C) and the extent of splicing inhibition determined by quantitation of the lariat–3′-exon and lariat intermediate bands using the UN-SCAN-IT program.

RESULTS

A variety of V-shaped and Y-shaped DNA and RNA synthetic inhibitors were synthesized according to the convergent bNA methodology described previously (Table 1) (37,38,40). Since the 2′ and 3′ sequences of the synthetic bNAs are identical, the branched core architecture is different from that of the wild-type consensus sequence (i.e. 5′..AA2′p5′G..3′p5′G.. versus 5′..AA2′p5′G..3′p5′C…; compare sequences in Table 1 and Fig. 1). However, this is probably inconsequential as studies on the branchpoint sequences demonstrate that mutation of the conserved 3′-C nucleotide to G has no discernible effect on splicing (54).

Table 1. Oligonucleotide sequences synthesized in this work.

| Code | Sequence (5′→3′) | Topology |

|---|---|---|

| Linear oligonucleotides | ||

| 1 | tac taa gta tgc | Linear DNA |

| 2 | UAC UAA GUA UGU | Linear RNA |

| 3 | UAC UAA GUA UCc | Linear RNA |

| 4 | UAC UAA GUA UGc | Linear RNA |

| V-shaped oligonucleotides | ||

| 5 | A2′,5′(gta tgc) 3′,5′gta tgc | V-DNA |

| 6 | A2′,5′(GUA UGc) 3′,5′GUA UGc | V-RNA |

| Y-shaped oligonucleotides | ||

| 7 | tac taA2′,5′(gta tgc) 3′,5′gta tgc | Y-DNA |

| 8 | UAC UAA2′,5′(GUA UGU) 3′,5′GUA UGU | Y-RNA |

| 9 | UAC UAA2′,5′(GUA UGc) 3′,5′GUA UGc | Y-RNA |

| 10 | UAC UAA2′,5′(GUA UGccc) 3′,5′GUA UGccc | Y-RNA |

| 11 | cUAC UAA2′,5′(GUA UGccc) 3′,5′GUA UGccc | Y-RNA |

| 12 | cccUAC UAA2′,5′(GUA UGccc) 3′,5′GUA UGccc | Y-RNA |

| 13 | cccUAC UAA2′,5′(GUA UGccc) 3′,5′GUA UGccc | Y-RNA |

| 14 | UAC UA(aA)2′,5′(GUA UGU)3′,5′GUA UGU | (ara-A)-Y-RNA |

| 15 | UAC UA(aA)2′,5′(GUA UGc)3′,5′GUA UGc | (ara-A)-Y-RNA |

Lower case letters = deoxynucleotide residues; upper case letters = ribonucleotide residues; bold letters = 2′-OMe-ribonucleotide residues; c = unnatural l-2′-deoxycytidine (L-dC); aA = arabino-adenosine branchpoint; 2′,5′X = 2′,5′-phosphodiester linkage; 3′,5′X =3′,5′-phosphodiester linkage.

Additional bDNA and bRNA sequences composed of terminal L-dC residues, 2′-O-methyl pyrimidine substitutions and a non-native araA branchpoint moiety were also prepared to assess their nuclease sensitivity during in vitro splicing as well as to determine their inhibitory potential (Table 1; compounds 5–15). Furthermore, linear DNA and RNA molecules (compounds 1–4) were also synthesized to help elucidate the affinity of factor binding for such sequences compared with bNAs of similar nucleotide composition. The conserved yeast lariat intronic sequence was maintained for the studies in mammalian extract since the UACUAAC branch region has been shown to be the optimal branch site recognition motif in both systems (20). This branch site sequence is known to form base pairs with the complementary sequence GUAGUA in U2 snRNA during mRNA splicing in the yeast (S.cerevisiae), thereby forcing the branchpoint adenosine nucleotide to bulge out of the helix (Fig. 1) (24). Even though mammalian branch sites conform only weakly to the YURAC consensus (Y = pyrimidines; R = purine), the GUAGUA element is preserved in mammalian U2 snRNA.

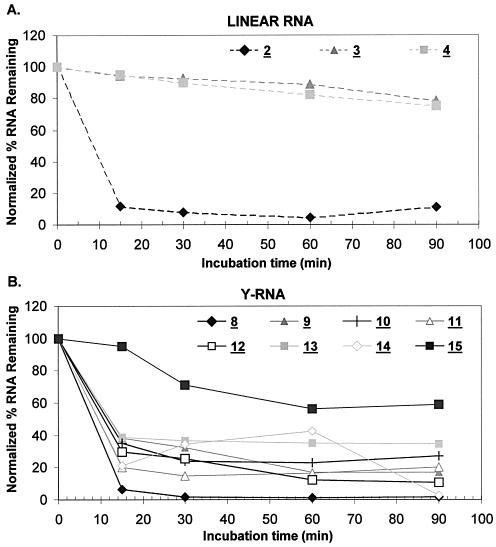

Nuclease sensitivity of linear and branched oligonucleotides in mammalian (HeLa) nuclear extract

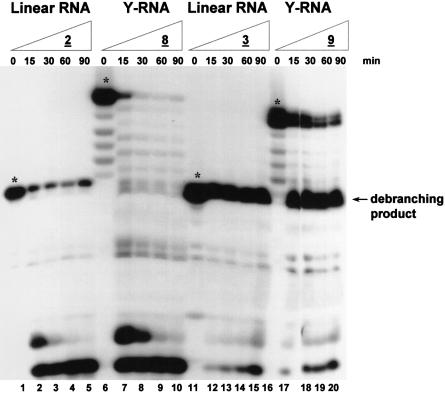

The nuclease resistance profiles of selected linear (compounds 2–4) and Y-shaped (compounds 8–11 and 12–15) RNAs were conducted under splicing conditions (i.e. 25% extract, T = 30°C) for variable lengths of time (t = 0–90 min). The degradation profiles of the various substrate RNAs revealed some interesting trends. As previously demonstrated for linear oligonucleotides (55), one insertion of an unnatural L-dC residue at the 3′ terminus of a bRNA was sufficient to provide adequate stability against the cellular exonucleases present in the extract. When linear RNA 2 (no 3′-L-dC residue) was incubated with the extract, a significant amount of degradation was obvious, even after 15 min (Fig. 2A, and Fig. 3, lanes 1–5), resulting in almost complete loss of the signal after the full 90 min. Alternatively, 3, a linear RNA bearing almost identical sequence composition, but incorporating one L-dC unit at the 3′ end, was highly resistant to the nuclease activity present in the extract (Fig. 2A, and Fig. 3, lanes 11–15). Similarly, the bNA 8 was completely degraded after 90 min (Fig. 2B, and Fig. 3, lanes 6–10), whereas the 3′-stabilized compound 9 demonstrated considerable resistance (Fig. 2B, and Fig. 3, lanes 16–20). Nonetheless, the amount of residual RNA in the more nuclease-resistant 9 was still decreasing with time, indicating that a competing hydrolysis reaction was occurring (Fig. 3; lanes 16–20). HeLa extract preparations typically contain the 2′-phosphodiesterase RNA-debranching activity (17). As such, 2′ debranching of the bRNA substrate 9 would result in the formation of a linear RNA oligonucleotide sequence identical to 3 (i.e. Y-RNA lacking the 2′ extension). Indeed, the accumulation of one main hydrolysis product was clearly evident, and its migratory rate was consistent with that of the linear debranching product 3 (Fig. 3; compare lanes 11–15 with 16–20). In fact, the nuclease resistance of this product dodecanucleotide is also undoubtedly seen, suggesting that although the 3′ termini of the bNA 9 are extremely resistant to cleavage, the disposition of the native branchpoint is a recognition element for hydrolysis by the HeLa debranching enzyme. Quantitation of the remaining RNA indicates that ∼60% of the Y-RNA 9 is debranched after only 15 min (Fig. 2B). This, however, was not the case for bNA 8. Debranching of 8 would produce the linear construct 2, which in turn would undergo degradation by exonucleases given that it lacks any stabilizing 3′ termini. Indeed, this is established by the absence of an accumulated debranched product band in the degradation profile of 8 (Fig. 3, lanes 6–10). Similarly, other 5′- and/or 3′-L-dC stabilized bRNAs (compounds 10, 11 and 12) demonstrated substantial resilience (compared with 8) to the exonuclease activity present in the nuclear extract (Fig. 3); however, debranching of the 2′ extension and accumulation of the nuclease-resistant linear products were also noteworthy (gel autoradiogram not shown). The similar degradation profiles exuded by the terminally modified bNAs (compounds 9–12) indicate that multiple L-dC inclusions at the 3′ terminus or at the 5′ terminus are unnecessary, establishing that a single L-dC insert at the 3′ end is enough to impart adequate nuclease resistance. Once again, the 5′-terminal modifications (11 and 12) did not appear to induce greater stability of the structures, suggesting that a negligible amount of 5′-exonucleases was present in the extract mixture.

Figure 2.

Charts demonstrating the nuclease stability of various linear RNAs (2–4) and Y-RNAs (8–11 and 12–15) under in vitro splicing conditions. (A) Nuclease sensistivity of linear RNAs 2–4 in the presence of HeLa extract. (B) Nuclease sensitivity of Y-RNAs 8–11 and 12–15 in the presence of HeLa extract. The percentage RNA remaining was determined by quantitation of the precursor Y-RNA bands divided by the total radioactivity in each lane in the respective autoradiograms and normalizing with respect to the t = 0 time point (100% RNA).

Figure 3.

Effect of unnatural L-dC termini on the nuclease stability of linear and Y-RNAs in HeLa nuclear extract. Y-RNAs were incubated with a 25% (v/v) HeLa extract under splicing conditions. KH2PO4 (50 mM) was added as a general phosphatase inhibitor (5 mM final concentration). Samples were resolved on a 16% denaturing gel (7 M urea) and the bands visualized by autoradiography. Starting compounds before incubation are identified with asterisks.

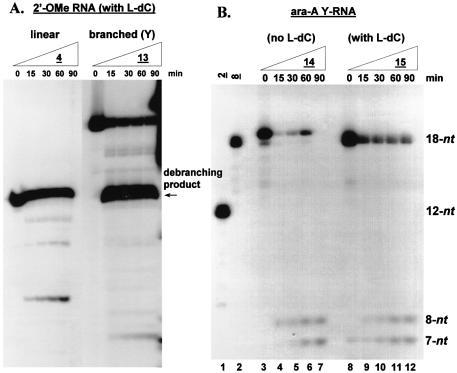

A second nuclease-resistant modification, 2′-O-methyl-ribonucleoside (i.e. 2′-OMe), was also investigated in both linear and Y-shaped RNA constructs (Table 1; compounds 4 and 13). Specifically, the ribopyrimidines (C and U) found in sequences 3 and 12 were replaced by 2′-OMe-ribopyrimidine units. Our rationale for this pyrimidine nucleotide modification stems from previous research conducted on the synthesis and stability profiles of synthetic ribozymes, in which alteration of the natural RNA pyrimidines to 2′-OMe substituents greatly enhanced the hydrolytic stability of the molecules in biological media (56). Additionally, such modifications were expected to have the same predominant sugar conformation as the native RNA constituents, namely C3′-endo (57,58). The degradation profile of the linear RNA oligonucleotide containing 2′-OMe-ribopyrimidine inserts (4) indicated that the compound was indeed nuclease resistant, however to the same degree as 3 which merely contained one 3′-L-dC unit (Figs 2A and 4A). Alternatively, the 2′-OMe-modified bNA 13 displayed a nuclease stability comparable with the 3′-L-dC-containing bNAs (9, 10 and 5) at shorter incubation times (15 and 30 min); however, at longer reaction times, the amount of residual RNA tapered off rather than degrading further (Figs 2B and 4A). This may suggest a stabilizing role for these constituents against endonucleases in the cellular extract. Analogous to the L-dC-modified bNAs, debranching of the 2′-OMe-modified bNA 13 was also clearly evident as established by the accumulation of one main product band with a migratory rate similar to that of the linear 2′-OMe construct 4.

Figure 4.

(A) Effect of incorporating 2′-O-methyl pyrimidine units and unnatural L-dC termini on the nuclease stability of Y-RNAs in HeLa nuclear extract. Y-RNAs were incubated with a 25% (v/v) HeLa extract under splicing conditions. KH2PO4 (50 mM) was added as a general phosphatase inhibitor. Samples were resolved on a 16% denaturing gel (7 M urea) and the bands visualized by autoradiography. (B) Effect of incorporating an arabino-adenosine (ara-A) branchpoint (14 and 15) and unnatural L-dC termini (15) on the nuclease stability of Y-RNAs in HeLa nuclear extract. Y-RNAs were incubated with a 25% (v/v) HeLa extract under splicing conditions. KH2PO4 (50 mM) was added as a general phosphatase inhibitor. Samples were resolved on a 16% denaturing gel (7 M urea) and the bands visualized by autoradiography.

Although ample protection is imparted by including a minimum of one terminal 3′-L-dC constituent into an otherwise unmodified bRNA structure, the fact remained that the 2′ extensions of the bNAs were highly vulnerable to the debranching activity present in the HeLa extract. Incorporation of a branchpoint modification that resists the 2′-scissile activity of the debranching enzyme would therefore increase the effective concentration of branch inhibitor in the pre-mRNA splicing assays. Recent work emerging from our research group has demonstrated that branched RNAs of sequence constitution identical to 8, however incorporating the 2′ epimer of riboadenosine at the branchpoint (i.e. ara-A, 14), is not a substrate for the yeast DBR (59). As such, compounds 14 and 15 containing an ara-A branchpoint were synthesized to examine their susceptibility to either or both exonuclease hydrolysis and the HeLa RNA-debranching activity (Table 1). Upon incubation with HeLa extract, bNA 14, which lacks an L-dC-modified 3′ terminus, is rapidly degraded (Fig. 2B, and Fig. 4B, lanes 3–7). Conversely, the L-dC-containing ara-A Y-RNA (15) is degraded much more slowly (Fig. 2B, and Fig. 4B, lanes 8–12). Most notably, however, is the absence of a 12 nucleotide 3′-L-dC stabilized debranching product in the case of 15 (Fig. 4B), demonstrating that bNAs containing an ara-A branchpoint are not substrates for the 2′-phosphodiesterase HeLa debranching activity. The amount of residual bNA 15 is probably higher than that demonstrated in Figures 2B and 4B since a considerable amount of 5′-dephosphorylation of the compound was also manifest. As such, bNA 15 displayed the highest nuclease resistance of all the bNAs studied (Fig. 2B), predominantly due to the fact that it is not a substrate for the RNA DBR.

Branched oligonucleotide recognition is influenced by the nature of the furanose sugar and nucleotides preceding the branchpoint

HeLa nuclear extract for in vitro splicing inhibition assays by exogenous bNAs were prepared according to the well-cited method of Dignam (51). Prior to the inhibition assays, the ability of the pre-mRNA transcript (PIP85.B) to splice effectively in HeLa extract was assessed (see Materials and Methods). Pre-mRNA splicing was conducted under the conditions described by Grabowski and co-workers (52) and employed 25% (v/v) HeLa nuclear extract per reaction at a final concentration of 60 mM KCl. Splicing of the 234 nt RNA transcript is indeed active under the employed conditions (Fig. 5, lanes 1 versus lane 2). Generation of the 109 nt mRNA is seen as early as 20 min into the reaction. Notably, as the reaction time progresses, the amounts of pre-mRNA (109 nt) and lariat–3′-exon intermediate (125 nt) suitably decrease, with a concomitant increase in the amount of spliced mRNA product (Supplementary Material S3). This discrete visualization of the lariat intermediate and products readily enabled us to dissect which, if any, of the two splicing steps were being affected by the bNA inhibitors. Whereas exogenous bNAs are rapidly debranched by the 2′-phosphodiesterase activity present in HeLa extracts, the lariat intron species (125 nt) accumulates under the splicing conditions described (Supplementary Material S3) (16,17,60). This consistently observed result indicates that the lariat RNA structure is protected from debranching by factor(s) present in the splicing pathway, since previous work in which the lariat–intron has been deproteinized and then added back to a splicing reaction shows that it is effectively linearized by cleavage at the 2′ position (17).

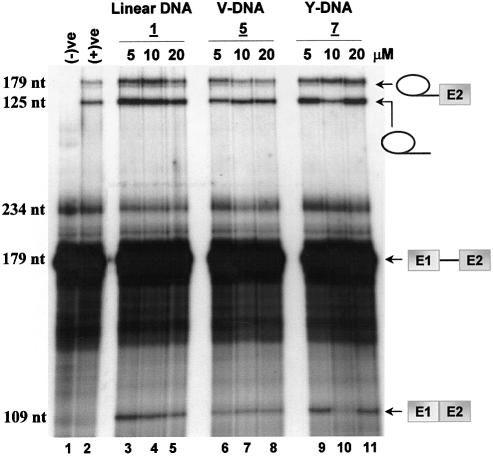

Figure 5.

Inhibition of pre-mRNA splicing in HeLa nuclear extract with variable concentrations (5–20 µM) of cold linear, V- and Y-shaped DNAs. Splicing reactions were stopped after 30 min. Intermediates and products were partitioned on a 15% (19:1 cross-link) denaturing gel (8 M urea) and visualized by autoradiography. The negative control [(–)ve] represents the pre-mRNA alone. The positive control [(+)ve] is the spliced RNA in the absence of any inhibitor.

Results on the splicing of the pre-mRNA substrate in the presence of increasing concentrations of linear (1), V-shaped (5) and Y-shaped (7) DNA oligonucleotides are shown in Figure 5. Specifically, none of the DNA oligonucleotides, linear or branched, was capable of inhibiting the formation of the mRNA product at the concentration ranges studied (5–20 µM). This was gauged by both qualitative and quantitative analysis, with which no notable decrease in the amount of lariat–3′-exon or lariat–intron product was observed with any of the DNA constructs (Fig. 5). Possibly, some inhibition might be observed at higher concentrations of oligonucleotide, although elevated concentrations (e.g. 100 µM) were not tested at this time.

A converse trend was observed with the RNA inhibitors, specifically the bRNAs. Linear RNA 3 was not an effective inhibitor of splicing (Fig. 6A, lanes 3–5, and B). Conversely, the V-RNA 6 was a much better inhibitor at higher concentrations (10–20 µM; Fig. 6A, lanes 9–11). The most pronounced effect was undoubtedly seen with the native Y-RNAs (10, 11 and 12). A decrease in the amount of lariat–3′-exon was visibly manifest with increasing concentration of all the bRNAs which demonstrated inhibitory potencies (i.e. IC50) in the 8–10 µM range (Fig. 6A and B).

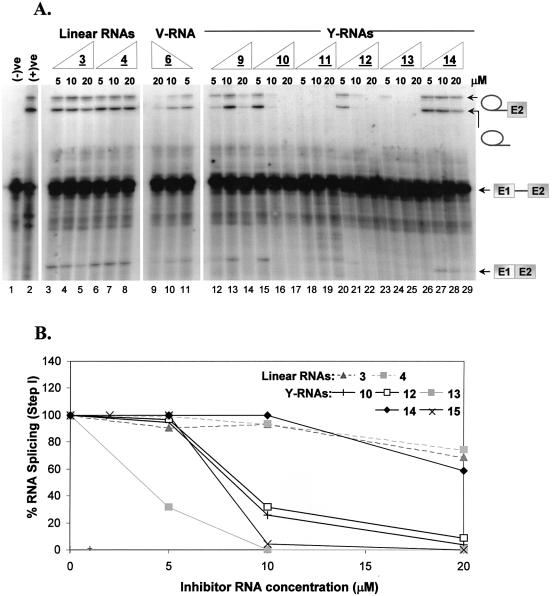

Figure 6.

(A) Inhibition of pre-mRNA splicing in HeLa nuclear extract with variable concentrations (5–20 µM) of cold linear, V- and Y-shaped RNAs. Splicing reactions were stopped after 30 min. Intermediates and products were partitioned on a 15% (19:1 cross-link) denaturing gel (8 M urea) and visualized by autoradiography. The negative control [(–)ve] represents the pre-mRNA alone. The positive control [(+)ve] is the spliced RNA in the absence of any inhibitor. (B) Chart demonstrating the inhibition of pre-mRNA splicing in HeLa nuclear extract with variable concentrations of representative linear RNAs (3 and 4) and Y-RNAs (10 and 12–15). The percentage RNA splicing (step I) was calculated by densitometric quantitation of the lariat–3′-exon intermediate product band and normalized with respect to the product band in the lane lacking any inhibitor (positive control).

The inhibitory activity of the 2′-OMe-ribopyrimidine-containing linear (4) and Y-RNA (13) were also suitably assessed given their ample nuclease resistance, and the predominant C3′-endo (RNA-like) sugar conformation. The linear 2′-OMe-pyrimidine-containing RNA 4 demonstrated a nearly identical inactivity towards splicing inhibition as its all RNA correlative 3 under the concentration range studied (Fig. 6A, lanes 6–8, and B). Alternatively, the 2′-sugar-modified bNA 13 displayed significant inhibitory potency (Fig. 6A, lanes 24–26, and B). Its activity, in terms of step I inhibition, was at least twice as potent as the most potent of the bRNAs containing no 2′ modifications, with an IC50 of ∼5 µM (Fig. 6B).

Inhibitory activity is maintained in a branched RNA containing a modified arabino-adenosine branchpoint

Although remarkable inhibitory potencies were achieved with the bRNAs described above, nuclease degradation profiles (Figs 2, 3 and 4A) undeniably established that 2′ debranching of the substrate bNAs was a serious drawback. This hydrolytic activity essentially reduces the effective concentration of bNA inhibitors during the splicing assays. As such, the concentrations reported are probably much lower than those observed in reality. Given this limitation, the debranching-resistant bNAs 14 and 15 (Table 1) were also investigated for their inhibitory potential. Under the splicing inhibition conditions described previously, bNA 14, which did not contain a 3′-L-dC stabilizing insert, appeared to inhibit step I of the RNA splicing reaction at 20 µM concentration (Fig. 6B and Supplementary Material S4). Conversely, a much lower concentration of bNA 15 was required to afford complete splicing abolition under the conditions employed (Fig. 6B and Supplementary Material S4). Furthermore, quantitative analysis of the lariat–3′-exon intermediate indicated that step I inhibition was occurring with as little at 0.5 µM of the bNA 15. This generous inhibitory activity seemingly indicates that the non-native ara-A has little bearing on recognition by the branch recognition factor (see Discussion).

Small, branched oligonucleotides are poor inhibitors of RNA splicing

Additional evidence supporting that branch recognition requires the presence of a fully defined branchpoint including 5′, 2′ and 3′ extensions was obtained with small, branched oligonucleotides, specifically trimers and tetramers. As expected, no activity was observed with the linear trimer AUC (Supplementary Material S5). When the trimers featured an adenosine branch core, as in the case of A(U)U, A(U)G and A(G)U, no inhibitory potential was also established under the concentration range investigated (5–20 µM). Although the A(G)U trimer contained the conserved 2′-G unit found in the natural lariats, it was still unable to promote inhibition of splicing activity. The same was true for the branched tetramer AA(G)G, which possessed the 2′-G residue in the structure (Supplementary Material S5). In fact, neither of the two branched tetramers UA(U)U or AA(G)G were active splicing inhibitors, regardless of the fact that they contained a single 5′ nucleotide off the branch. Contrarily, the longer Y-shaped decanucleotide species cUUA(GUc)GUc demonstrated some potency at higher concentrations (i.e. 10–20 µM). This further supports the notion that branch recognition is dependent upon the sequences directly adjacent to the branchpoint nucleotides (i.e. significant inhibition requires that the branched compounds bear a 5′ extension).

DISCUSSION

A wealth of information regarding the interactions between various pre-spliceosomal and spliceosomal factors and the BPS adenosine moiety prior to branch (i.e. lariat) formation is available. However, little is known about the events surrounding branchpoint recognition after step I is complete. Obviously, the chemical involvement of the branch site adenosine is only during step I and not in the second step (i.e. exon ligation); nevertheless, the identity of the adenine base is critical for both steps (35,61). Particularly, an adenine to guanine base change imposes a strong block to step II, as well as a considerable decrease to step I (31,62), suggesting that the nature and topology of the branch containing vicinal 3′,5′- and 2′,5′-phosphodiester linkages is important for interactions specific to the second step activation mechanism (63).

These observations prompted us to prepare a series of bNAs, and study the effects of such bNAs on the efficiency of mammalian pre-mRNA splicing in vitro. Here we show that Y-shaped RNAs containing a minimum of one unnatural L-dC unit at their 3′ termini are highly stabilized against exonuclease hydrolysis in HeLa nuclear extracts, and are potent inhibitors of the splicing pathway.

The lack of inhibition imparted by the branched DNA substrates (e.g. Y-DNA 7) suggests that the 2′-hydroxyl units and/or the backbone sugar conformation enclosed within RNA oligonucleotides are requisite signals for proper spliceosomal recognition and effective splicing. Indeed, previous work has shown that incorporation of modified nucleotides, particularly deoxynucleotides at either the 3′ splice site (53) or the branchpoint (31), results in deleterious effects on the overall splicing reaction. Furthermore, seeing that V-RNAs (e.g. 6) are not as potent as Y-RNAs establishes that recognition of bNAs not only involves the branch core structure itself, but also the sequences upstream of the branch site. The requirement for a fully formed branch was supported by the inactive inhibitory profiles demonstrated by small, branched trimers and tetramers. Alternatively, the disparity in activity demonstrated by the V- and Y-shaped RNA might also suggest that the three-dimensional structure of the bNA is a valuable recognition motif. Specifically, conformational and NMR studies on branched tri- and tetranucleotides have revealed that the branchpoint adenine base is heavily involved in an intramolecular base stacking interaction between the G-nucleotide at the 2′ position and the purine moiety at the 5′ position off the branch (64,65). Furthermore, the ribose sugar of the branchpoint adenosine appears to adopt a preferred C2′-endo sugar pucker in such structures. Such a localized effect is speculated to serve as a point of local distortion in the normal A-type RNA helix (65) and, as such, may act as a signal for recognition by a putative branch recognition factor.

Given that the lariat–3′-exon and lariat–intron species were adequately resolved by gel electrophoresis, it was possible to dissect which of the two chemical steps (either step I or step II) of the splicing reaction was being affected by the bRNAs. The concurrent decrease in the amount of lariat–3′-exon product (step I product) and lariat–intron (step II product) undeniably ascertains that binding and sequestering of the branch recognition factor by the bNAs is an early event, which occurs prior to the first chemical step of splicing. Potentially, an early recognition element such as the p14 (35) or mBBP (28,29) protein factors or even the U2 snRNP may be preferentially recognizing the synthetic branched molecules over the native pre-mRNA. The U2 snRNP is a likely candidate for such a recognition event since it is well established that it partakes in early spliceosomal assembly (24,25). Additionally, it is well recognized that U2 snRNA (a component of U2 snRNP) makes direct contact with the pre-branchpoint region, as substantiated by a site-specific cross-linking interaction between a pre-mRNA substrate and the U2 snRNA (63). Most importantly, the U2 snRNA has also been shown to remain bound to the lariat–3′-exon intermediate following the first transesterification reaction (66), indicating that the folded snRNA structure probably contains a branch recognition domain. As such, it is possible that this U2 snRNA/lariat–3′-exon interaction is responsible for debranching resistance flaunted by the lariat intermediate during the splicing reaction (16,17,60). Conversely, since the linear control RNAs have little or no inhibitory effect, which would be expected if these were binding to U2 snRNP (via U2 snRNA) by base pairing, it may be argued that the inhibition observed results from the sequestering of another factor, possibly a U2 snRNP-associated factor that specifically interacts with the branched branchpoint. Whatever the nature of this reputed splicing factor, it is clearly apparent that it demonstrates a much higher affinity for the Y-RNA structures relative to linear constructs of similar sequence composition (compare 3 and 10).

Antisense oligonucleotides containing 2′-OMe modifications to the ribose sugar have been effectively exploited for the isolation of ribonucleoprotein complexes, specifically snRNAs (43,67). Their utility stems from the fact that they are highly nuclease resistant and generally form more stable hybrid duplexes with a complementary RNA sequence than the native RNA (57,58). Typically the increase in thermal stability of such 2′-OMe constituents is of the order of 1.5–2°C per modification (57). Our present study revealed that a branched RNA containing 2′-OMe-ribopyrimidine insertions (i.e. bNA 13) was an exceptionally potent inhibitor of pre-mRNA splicing. Apart from the mildly increased stabilization displayed by this compound, presumably against endonucleases present in the HeLa extract, the compound also displayed preferential splicing inhibition compared with the native bRNAs. Seemingly, this enhancement may be a result of tighter binding to the branch recognition factor, specifically if it is an snRNA. The activity of bRNA 13, in terms of step I inhibition, was at least twice as potent as the most potent of the bRNAs containing no 2′ modifications, with an IC50 of ∼5 µM (Fig. 6B). This result suggests that the C3′-endo sugar conformation retained in all the constituents of 2′-modified bNA 13 allows for extremely effective recognition by the reputed branch recognition factor. Additionally, should this factor be an snRNA (i.e. U2 snRNA), the enhancement in activity may be due to the fact that tighter binding in the complex is achieved owing to the 2′-OMe substituents (57). While several 2′-OMe-pyrimidine units were needed to achieve the desired C3′-endo conformation/nuclease resistance for the entire sequence, the precise number of modified units needed to reach the highest level of inhibition remains to be determined.

Our results with the arabinose-containing branchpoint (15) affirm that this type of branched oligonucleotide is not a substrate for the 2′-scissile activity (debranching activity) found in HeLa nuclear extract (59). Since it is likely that both arabinose and ribose branchpoints adopt a South or C2′-endo conformation (64,68,69), we can speculate that the equatorial disposition of the 2′-OH group in ribose (versus axial in arabinose) is an important factor in the debranching reaction. Moreover, the resistance of 15 towards 2′ debranching appears to be beneficial since it would substantially increase the effective concentration of inhibitor present throughout the reaction. In comparison with 13, the best inhibitor from the ribose-containing branchpoint series, 15, appeared to be slightly less potent at identical concentrations (i.e. 5 µM; Fig. 6B). While the sugar conformation adopted by the arabinose sugar at this branch position has not been fully validated, studies on a branched trinucleotide diphosphate containing an ara-A branchpoint have implied that the adenine heterocycle is capable of a base–base stacking interaction with the residue at the 2′ position, similar to the native ribose branchpoint (64). Mutation of a conserved riboadenosine unit for an ara-A moiety in a pre-branched pre-mRNA substrate provided compelling evidence that this unit is capable of occupying a ‘bulged’ position, similar to the riboadenosine residue when bound to the GUAGUA region of the U2 snRNA (31). These combined results suggest that a similar point of local A-like distortion is proably observed with the arabinose modification, and may also act as a underlying motif for branch recognition. This again suggests that the branch recognition element is an early binding factor, which recognizes the bNAs during the initial spliceosomal assembly events.

Given this abundance of information, studies on the affinity purification and biochemical analysis of the branch recognition factor are now possible. Such experiments are currently being pursued.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Material is available at NAR Online.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the referees for valuable comments and insight. Funding was generously provided by NSERC Canada. S.C. acknowledges a postgraduate scholarship from FCAR (Quebec).

REFERENCES

- 1.Chow L.T., Gelinas,R.E., Broker,T.R. and Roberts,R.J. (1977) An amazing sequence arrangement at the 5′-ends of adenovirus 2 messenger RNA. Cell, 12, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berget S.M., Moore,C. and Sharp,P.A. (1977) Spliced segments at the 5′ terminus of adenovirus 2 late mRNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 74, 3171–3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Madhani H.D. and Guthrie,C. (1994) Dynamic RNA–RNA interactions in the spliceosome. Annu. Rev. Genet., 28, 1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore M.J., Query,C.C. and Sharp,P.A. (1993) Splicing of precursors to mRNA by the spliceosome. In Gesteland,R. and Atkins,J. (eds), The RNA World. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, pp. 303–357. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nilsen T.W. (1994) RNA–RNA interactions in the spliceosome: unraveling the ties that bind. Cell, 78, 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reed R. (2000) Mechanisms of fidelity in pre-mRNA splicing. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 12, 340–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins C.A. and Guthrie,C. (2000) The question remains: is the spliceosome a ribozyme? Nature Struct. Biol., 7, 850–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tuschl T., Sharp,P.A. and Bartel,D.P. (2001) A ribozyme selected from variants of U6 snRNA promotes 2′,5′-branch formation. RNA, 7, 29–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Villa T., Pleiss,J.A. and Guthrie,C. (2002) Spliceosomal snRNAs: Mg2+-dependent chemistry at the catalytic core? Cell, 109, 149–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valadkhan S. and Manley,J.L. (2001) Splicing-related catalysis by protein-free snRNAs. Nature, 413, 701–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valadkhan S. and Manley,J.L. (2003) Characterization of the catalytic activity of U2 and U6 snRNAs. RNA, 9, 892–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brody E. and Abelson,J. (1985) The ‘spliceosome’: yeast pre-messenger RNA associates with a 40S complex in a splicing-dependent reaction. Science, 228, 965–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou Z., Licklider,L.J., Gygi,S.P. and Reed,R. (2002) Comprehensive proteomic analysis of the human spliceosome. Nature, 419, 182–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallace J.C. and Edmonds,M. (1983) Polyadenylated nuclear RNA contains branches. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 80, 950–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keller W. (1984) The RNA lariat: a new ring to the splicing of mRNA precursors. Cell, 39, 423–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruskin B., Krainer,A.R., Maniatis,T. and Green,M.R. (1984) Excision of an intact intron as a novel lariat structure during pre-mRNA splicing in vitro. Cell, 38, 317–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruskin B. and Green,M.R. (1985) An RNA processing activity that debranches RNA lariats. Science, 229, 135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacquier A., Rodriguez,J.R. and Rosbash,M. (1985) A quantitative analysis of the effects of 5′ junction and TACTAAC box mutants and mutant combinations on yeast mRNA splicing. Cell, 43, 423–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reed R. and Maniatis,T. (1988) The role of the mammalian branchpoint sequence in pre-mRNA splicing. Genes Dev., 2, 1268–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhuang Y., Goldstein,A.M. and Weiner,A.M. (1989) UACUAAC is the preferred branch site for mammalian mRNA splicing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 86, 2752–2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madhani H.D. and Guthrie,C. (1992) A novel base-pairing interaction between U2 and U6 snRNAs suggests a mechanism for the catalytic activation of the spliceosome. Cell, 71, 803–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wassarman D.A. and Steitz,J.A. (1993) A base-pairing interaction between U2 and U6 small nuclear RNAs occurs in >150S complexes in HeLa cell extracts: implications for the spliceosome assembly pathway. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 7139–7143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu J. and Manley,J.L. (1991) Base pairing between U2 and U6 snRNAs is necessary for splicing of a mammalian pre-mRNA. Nature, 352, 818–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parker R., Siciliano,P.G. and Gurthrie,C. (1987) Recognition of the TACTAAC box during mRNA splicing in yeast involves base pairing to the U2-like snRNA. Cell, 49, 229–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu J. and Manley,J. (1989) Mammalian pre-mRNA branch site selection by U2 snRNP involves base pairing. Genes Dev., 3, 1553–1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhuang Y. and Weiner,A. (1989) A compensatory base change in human U2 snRNA can suppress a branch site mutation. Genes Dev., 3, 1545–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yan D. and Ares,M.,Jr (1996) Invariant U2 RNA sequences bordering the branchpoint recognition region are essential for interaction with yeast SF3a and SF3b subunits. Mol. Cell. Biol., 16, 818–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berglund A.J., Chua,K., Abovich,N., Reed,R. and Rosbash,M. (1997) The splicing factor BBP interacts specifically with the pre-mRNA branchpoint sequence UACUAAC. Cell, 89, 781–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arning S., Gruter,P., Bilbe,G. and Kramer,A. (1996) Mammalian splicing factor SF1 is encoded by variant cDNAs and binds to RNA. RNA, 2, 794–810. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rutz B. and Seraphin,B. (1999) Transient interaction of BBP/ScSF1 and Mud2 with the splicing machinery affects the kinetics of spliceosome assembly. RNA, 5, 819–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Query C.C., Moore,M.J. and Sharp,P.A. (1994) Branched nucleophile selection in pre-mRNA splicing: evidence for the bulged duplex model. Genes Dev., 8, 587–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berglund J.A., Rosbash,M. and Schultz,S.C. (2001) Crystal structure of a model branchpoint–U2 snRNA duplex containing bulged adenosines. RNA, 7, 682–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.MacMillan A.M., Query,C.C., Allerson,C.R., Chen,S., Verdine,G.L. and Sharp,P.A. (1994) Dynamic association of proteins with the pre-mRNA branch region. Genes Dev., 8, 3008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chiara M.D., Gozani,O., Bennett,M., Champion-Arnaud,P., Palandjian,L. and Reed,R. (1996) Identification of proteins that interact with exon sequnces, splice sites and the branchpoint sequence during each stage of spliceosome assembly. Mol. Cell. Biol., 16, 3317–3326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Query C.C., Strobel,S.A. and Sharp,P.A. (1996) Three recognition events at the branch-site adenine. Eur. Mol. Biol. J., 15, 1392–1402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Damha M.J. and Ogilvie,K.K. (1988) Synthesis and spectroscopic analysis of branched RNA fragments: messenger RNA splicing intermediates. J. Org. Chem., 53, 3710–3722. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Damha M.J. and Zabarylo,S. (1989) Automated solid-phase synthesis of branched oligonucleotides. Tetrahedron Lett., 30, 6295–6298. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Damha M.J., Ganeshan,K., Hudson,R.H.E. and Zabarylo,S.V. (1992) Solid-phase synthesis of branched oligoribonucleotides related to messenger RNA splicing intermediates. Nucleic Acids Res., 20, 6565–6573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ganeshan K., Tadey,T., Nam,K., Braich,R., Purdy,W.C., Boeke,J.D. and Damha,M.J. (1995) Novel approaches to the synthesis and analysis of branched RNA. Nucl. Nucl., 14, 1009–1013. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carriero S. and Damha,M.J. (2002) Solid-phase synthesis of branched oligonucleotides. In Beaucage,S. (ed.), Current Protocols in Nucleic Acid Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons, Vol. 4.14, pp. 1–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maschhoff K. and Padgett,R. (1993) The stereochemical course of the first step of pre-mRNA splicing. Nucleic Acids Res., 21, 5456–5462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moore M.J. and Sharp,P.A. (1993) The stereochemistry of pre-mRNA splicing: evidence for two active sites in the spliceosome. Nature, 365, 364–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ryder U., Sproat,B.S. and Lamond,A.I. (1990) Sequence-specific affinity selection of mammalian splicing complexes. Nucleic Acids Res., 18, 7373–7379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carriero S., Braich,R.S., Hudson,R.H.E., Anglin,D., Friesen,J.D. and Damha,M.J. (2001) Inhibition of in-vitro pre-mRNA splicing in S.cerevisiae by branched oligonucleotides. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids, 20, 873–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stevens S.W. and Abelson,J. (2002) Yeast pre-mRNA splicing: methods, mechanisms and machinery. Methods Enzymol., 351, 200–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hernandez N. and Keller,W. (1983) Splicing of in vitro synthesized messenger RNA precursors in HeLa extract. Cell, 35, 89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Padgett R.A., Hardy,S.F. and Sharp,P.A. (1983) Splicing of adenovirus RNA in a cell-free transcription system. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 80, 5230–5234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krainer A.R., Maniatis,T., Ruskin,B. and Green,M.R. (1984) Normal and mutant human β-globin pre-mRNAs are faithfully and efficiently spliced in vitro. Cell, 36, 993–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Asara J.M. and Allison,J. (1999) Enhanced detection of oligonucleotides in UV MALDI MS using the tetraamine spermine as a matrix additive. Anal. Chem., 71, 2866–2870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lecchi P., Le,H.M.T. and Pannell,L.K. (1995) 6-Aza-2-thiothymine: a matrix for MALDI spectra of oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res., 23, 1276–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dignam J.D., Lebovitz,R.M. and Roeder,R.G. (1983) Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res., 11, 1475–1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grabowski P.J., Padgett,R.A. and Sharp,P.A. (1984) Messenger RNA splicing in vitro: an excised intervening sequence and a potential intermediate. Cell, 37, 415–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moore M.J. and Sharp,P.A. (1992) Site-specific modification of pre-mRNA: the 2′-hydroxyl groups at the splice sites. Science, 256, 992–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fouser L.A. and Friesen,J.D. (1986) Mutations in a yeast intron demonstrate the importance of specific conserved nucleotides for the 2 stages of nuclear messenger-RNA splicing. Cell, 45, 81–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Damha M.J., Giannaris,P.A. and Marfey,P. (1994) Antisense l/d-oligodeoxynucleotide chimeras: nuclease stability, base-pairing properties and activity at directing ribonuclease H. Biochemistry, 33, 7877–7885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Beigelman L., McSwiggen,J.A., Draper,K.G., Gonzalez,C., Jensen,K., Karpeisky,A.M., Modak,A.S., Matulic-Adamic,J., DiRenzo,A.B., Haeberli,P., Sweedler,D., Tracz,D., Grimm,S., Wincott,F.E., Thackray,V.G. and Usman,N. (1995) Chemical modification of hammerhead ribozymes. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 25702–25708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Freier S.M. and Altmann,K.-H. (1997) The ups and downs of nucleic acid duplex stability: structure–stability studies on chemically modified DNA:RNA duplexes. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 4429–4443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Manoharan M. (1999) 2′-Carbohydrate modifications in antisense oligonucleotide therapy: importance of conformation, configuration and conjugation. Biochim. Biophys Acta, 1489, 117–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carriero S., Mangos,M.M., Agha,K.A., Noronha,A.M. and Damha,M.J. (2003) Branchpoint sugar stereochemistry determines the hydrolytic susceptibility of branched RNA fragments by yDBR. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids, 22, 1599–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Domdey H., Apostol,B., Lin,R.-J., Newman,A., Brody,E. and Abelson,J. (1984) Lariat structures are in vivo intermeduates in yeast pre-mRNA splicing. Cell, 39, 611–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Query C.C., Strobel,S.A. and Sharp,P.A. (1995) The branch site adenosine is recognized differently for the two steps of pre-mRNA splicing. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser., 33, 224–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Freyer G.A., Arenas,J., Perkins,K.K., Furneaux,H.M., Pick,L., Young,B., Roberts,R.J. and Hurwitz,J. (1987) In vitro formation of a lariat structure containing a G2′–5′G linkage. J. Biol. Chem., 262, 4267–4273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gaur R.K., Valcarcel,J. and Green,M.R. (1995) Sequential recognition of the pre-mRNA branch point by U2AF65 and a novel spliceosome-associated 28-kDa protein. RNA, 1, 407–417. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Damha M.J. and Ogilvie,K.K. (1988) Conformational properties of branched RNA fragments in aqueous solution. Biochemistry, 27, 6403–6416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sund C., Agback,P., Koole,L.H., Sandstrom,A. and Chattopadhyaya,J. (1992) Assessment of competing 2′–5′ versus 3′–5′ stackings in solution structure of branched-RNA by 1H- and 31P-NMR spectroscopy. Tetrahedron, 48, 695–718. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chabot B. and Steitz,J. (1987) Multiple interactions between the splicing substrate and small nuclear ribonucleoproteins in spliceosomes. Mol. Cell. Biol., 7, 281–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lamond A.I. and Sproat,B.S. (1994) Isolation and characterization of ribonucleoprotein complexes. In Higgins,S.J. and Hames,B.D. (eds), RNA Processing: A Practical Approach. IRL Press, New York, Vol. I, pp. 103–140. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wilds C.J. and Damha,M.J. (1999) Duplex recognition by oligonucleotides containing 2′-deoxy-2′-fluoro-d-arabinose and 2′-deoxy-2′-fluoro-d-ribose. Intermolecular [2′OH ⇔ phosphate] contacts versus sugar puckering in the stabilization of triple helical complexes. Bioconjugate Chem., 10, 299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Noronha A.M. and Damha,M.J. (1998) Triple helices containing arabinonucleotides in the third (Hoogsteen) strand: effects of inverted stereochemistry at the 2′-position of the sugar moiety. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 2665–2671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.