Abstract

Background

Incremental sublingual triazolam has emerged as a popular sedation technique. Nevertheless, little research has evaluated the technique’s safety or efficacy. Given its popularity, an easily administered rescue strategy is needed.

Methods

We conducted an RCT to investigate how intraoral submucosal flumazenil (0.2 mg) attenuates CNS depression produced by incremental sublingual dosing of triazolam (3 doses of 0.25 mg over 90 minutes) in 14 adult subjects. Outcomes were assessed with the Observer Assessment of Alertness/Sedation (OAA/S) scale, BIS and physiological monitoring.

Results

OAA/S and BIS scores increased after flumazenil injection at the 30-minute observation point, but were not sustained. Six hours after the initial dose of triazolam (4 hours after flumazenil or placebo challenge), all could be discharged.

Conclusions

Deep sedation from sequential triazolam is incompletely reversed by a single intraoral injection. Reversal did not persist: discharge was at 360 minutes.

Clinical Implications

A single intraoral injection of flumazenil at 0.2 mg cannot be used to immediately rescue oversedation with triazolam. A larger dose might be effective. Reversal for discharging the patient early is neither appropriate nor safe.

Keywords: flumazenil, triazolam, sedation/sublingual, behavior/drug effects, dental anxiety/drug therapy, conscious sedation, patient safety

Dentists are increasingly interested in pharmacological tools to address high levels of fear and anxiety about dental care among the US population that result in oral health disparities among those who are fearful.1–3 Effective sedation techniques are needed that are safe and effective in the hands of general dentists without formal anesthesia training.4

Benzodiazepines are well suited to reduce anxiety during dental treatment in community practice. In general, drugs in this class can be expected to produce a dose-dependent central nervous system (CNS) depression, anxiolysis, and in some cases amnesia. Among the benzodiazepines, triazolam has become popular. While originally marketed for the treatment of insomnia, triazolam has pharmacological, behavioral, and safety characteristics that make it useful in dental settings.5–16 Among general dentists the incremental sublingual (SL) administration of triazolam has emerged as a sedation technique for fearful patients.4 Nevertheless, there is little research that has evaluated the technique’s safety or efficacy. This is significant because the administration of triazolam in this way carries the ability to deliver total doses that are in excess of what is commonly accepted as the maximum recommended dose, increase patient risk, and evoke unwanted side effects. The recommended dose for insomnia is 0.25 mg orally before bedtime over no more than 7 to 10 days. A dose of 0.5 mg is at the upper limit for this indication.17 A mail survey carried out of members of the Dental Organization for Conscious Sedation (DOCS) reviewed 7740 cases, of which 1686 (21%) included an adverse event. Incremental enteral sedation alone or in combination with nitrous oxide and oxygen was most commonly used. The most frequent event was a decrease in diastolic blood pressure of more than 25 percent and was related to less practitioner experience in incremental sedation practice but not training.18

Given the growing popularity of this incompletely studied sedation technique with general dentists, a safe, effective and easily administered pharmacologic rescue strategy is needed. Flumazenil (Romazicon®) is a competitive receptor antagonist selective for benzodiazepines and is indicated for suspected benzodiazepine overdose. The intravenous (IV) titration of the drug is capable of completely reversing any of the sedative effects of benzodiazepines; albeit, the length of action after reversal may be shorter than the drug effect being treated.19 While flumazenil is to be administered intravenously, there are reports of it being effective when administered nasally,20 rectally, 21 or via an endotracheal tube.22 Submucosal (SM) injections have been studied in dogs.23

We carried out this preliminary study to investigate the safety and clinical effectiveness of a single intraoral submucosal injection of flumazenil for use as a rescue strategy. Specifically, we conducted a double-blind, randomized trial to investigate the degree to which a single intraoral SM administration of flumazenil (0.2 mg) is capable of attenuating the CNS depression produced by a paradigm of incremental SL dosing of triazolam (3 doses of 0.25 mg over 90 minutes) and the duration of its effect.

METHODS

Subjects

Fourteen healthy adults between the age of 18 and 40 years participated in the study. Study participants were selected from 18 respondents to a campus poster seeking research subjects for a study about a sedative medication used in dentistry.

Exclusion criteria included a medical history significant for systemic disease (American Society of Anesthesiologists, ASA Class II or greater), use of benzodiazepines, anxiolytics or any other medications that would interact with either triazolam or flumazenil metabolism or clinical effect (including herbals) within four weeks of the study, body mass index (BMI) no less than 15 kg/m2 and no greater than 30 kg/m2, pregnancy or not currently using pharmacologic methods of birth control, allergy or sensitivity to benzodiazepines, history of a seizure disorder and chronic tobacco use. Of the 18 potential subjects, three were excluded because of the drug exclusion and one because of scheduling conflicts.

Because the intraoral SM injection of flumazenil is not an approved route of administration, Investigational New Drug (IND) approval was obtained from the Food and Drug Administration, which also limited the sample size and choice of study design. Subsequently, the Institutional Review Board of the University of Washington approved the protocol, and the informed consent of all subjects was obtained.

Study Design

We compared an active treatment condition (flumazenil, 2 mL, 0.2 mg SM) to a placebo control (0.9% saline, 2 mL, SM) administered 30 minutes after the last incremental SL dose of triazolam (0.75 mg total). We chose 0.2 mg for this first study because it was the lowest dose that might be expected to be effective and because 2mL was a clinically reasonable amount to inject intraorally. Subjects were randomly assigned to either Group A (flumazenil, n=7) or Group B (placebo, n=7) using a computer algorithm.

Measures

Sedation was measured at baseline and every 30 minutes after the first SL triazolam dose by a trained clinical observer using the Observer Assessment of Alertness/Sedation (OAA/S) who was blinded to treatment assignment. The decision to collect sedation data every 30 minutes was based on preliminary data in which peak effects of flumazenil reversal were observed at approximately 20 minutes.24 The OAA/S scale measures the level of sedation using four categories: responsiveness, speech, facial expression, and ocular appearance.25 The subject’s composite score is derived from the lowest score in any of the four categories. A bispectral index (BIS) monitor (Aspect Medical Systems, Newton, MA) was also applied to the forehead of each subject and used to assess triazolam-induced changes in the electroencephalogram. The BIS uses the frequency and amplitude of electroencephalogram signals to calculate a dimensionless index that ranges between 0 and 100, where lower scores indicate diminished activity.26–29 The study anesthesiologist, who was also blinded to treatment assignment, recorded the BIS scores, which were not available to the clinical observer who performed the OAA/S. Blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, and hemoglobin saturation (SaO2) were recorded at baseline and at 30 minute intervals, coinciding with OAA/S and BIS assessments. The oral mucosa at the site of the injection was evaluated clinically at the completion of the study and 24 hours later.

Procedures

Subjects had no food or drink for at least six hours before study procedures. Subjects were seated in a dental operatory, had noninvasive monitors applied for measuring vital signs (blood pressure, heart rate, hemoglobin saturation), and baseline vital signs were recorded.

The timing and amount of the three incremental triazolam doses was based on conversations with networks of dentists that use incremental triazolam dosing strategies as part of their clinical practice, and duplicates the dosing protocol of a companion laboratory trial we conducted.30 After the collection of all baseline data, subjects received 0.25 mg triazolam (Halcion®, Pharmacia & Upjohn Co., Kalamazoo, MI), with instructions to let the tablet dissolve under the tongue. Dissolution of the tablet was verified by visual inspection under the tongue 2–3 minutes after dosing. Additional SL triazolam doses were administered with the same instructions 60 minutes (0.25 mg) and 90 minutes (0.25 mg) later, for a total triazolam dose of 0.75 mg.

All subjects were randomly assigned to receive either a single intraoral SM injection of 0.2 mg flumazenil (Group A) or an equal volume of 0.9% saline (Group B) 30 minutes after the last dose of triazolam (T120). The intraoral site of this injection was the maxillary posterior vestibule. Subjects were placed in a semi-supine position, the cheek reflected and the mucosa of the mucobuccal fold adjacent to the maxillary second premolar and first molar wiped dry with sterile gauze. The syringes containing the flumazenil or 0.9% saline were identical and the observer making sedation assessments was blinded to group assignment. The long axis of the 25-gauge needle of the syringe was parallel to the maxillary buccal plate with the bevel facing the bone when it penetrated the mucosa in the mucobuccal fold and was advanced approximately 2 mm. The syringe was then aspirated and if negative, the 2 mL contained in the syringe was injected over the course of 60 seconds. If the aspiration was positive, the needle position was adjusted until the aspiration was negative. Sedation continued to be measured every 30 minutes, until the end of the study (6 hours after the first does of SL triazolam).

Subjects were discharged home when the anesthesiologist’s discharge criteria had been met, including a sustained level of consciousness in which the subjects engaged in purposeful verbal conversation, had stable vital signs comparable to their baseline, and were not in danger of compromising their airway.

Analysis

All results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Independent t-tests were conducted comparing the sedation scores of the conditions at each of three time points. In addition, t-tests were used to compare sedation levels across time points.

RESULTS

Subject and Procedure Descriptions

The mean age of the 14 subjects participating in this study was 25± 4 years (range = 21–36 years). Their mean height and weight were 176 ± 9 cm (range = 157.5 – 190.5 cm) and 74±11.6 kg (range = 52.62 – 99.79 kg), respectively. The mean BMI was 24 ± 2 kg/m2 (range = 20–28 kg/m2). Six of 14 participants were female. Table 1 summarizes this data by group (flumazenil or placebo).

Table 1.

Subject Demographics by Group (mean ± standard deviation)

| Study Groups | Age in years | Sex (M:F) | BMI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo: n=7 | 24±2 (22, 27) | 4:3 | 23±2 (20, 26) |

| Flumazenil: n=7 | 26±6 (21, 36) | 4:3 | 24±2 (21, 28) |

range (minimum and maximum) presented in parentheses

Triazolam Clinical Effects

As expected from our previously published research of incremental sublingual dosing of triazolam over 90 minutes30, 0.75 mg reliably produced time-dependent CNS depression as measured by BIS and OAA/S. At 120 minutes (30 minutes after the final dose of triazolam) the magnitude of the CNS depression was consistent with moderate sedation in both groups (pooled BIS: 65±14; pooled OAA/S: 3±1). Table 2 summarizes the BIS and OAA/S data by group. There was no difference in the average BIS and OAA/S scores of the two groups at 120 minutes (t=0.237. p=0.82; t<0.001, p=1.0 respectively).

Table 2.

Time- and Drug-Dependent Changes in Sedation Measures: Bispectral Data (BIS) and Observers Assessment of Alertness/Sedation (OAA/S)

| 0 min | 30 min | 60 min | 90 min | 120 mina | 150 min | 180 min | 210 min | 240 min | 270 min | 300 min | 330 min | 360 min | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIS | |||||||||||||

| Placebo | 95.9±2.2 (93, 98) | 91.1±6.1 (83, 98) | 85.2±16.9 (49, 98) | 82.2±6.4 (72, 89) | 66.6±15.9 (45, 87) | 74.3±9.1 (56, 81) | 61.4±20.3 (47, 96) | 71.1±16.6 (45, 95) | 72±15.4 (49, 91) | 73.9±15.2 (45, 94) | 78.6±13.4 (55, 87) | 82.5±13.4 (65, 98) | 89.9±11.3 (70, 98) |

| Flumazenil | 97±1.05 (95.3, 98) | 93±8.1 (76.5, 98) | 76.8±19.6 (52.5, 98) | 67.6±18.7 (40, 92.5) | 63.8±13.3 (58, 79) | 78.8±13.4 (51.5, 92) | 65.8±19.3 (46, 98) | 59.1±12.3 (41.8, 74) | 60.3±13.3 (42.8, 74.5) | 65.8±15.8 (44.8, 86.5) | 73±5.3 (65, 81.5) | 78.6±10.6 (72, 97.8) | 90.4±12.8 (62, 98) |

| OAA/S | |||||||||||||

| Placebo | 5±0 (5, 5) | 4.9±0.4 (4, 5) | 4.3±0.5 (4, 5) | 3.9±0.4 (3, 4) | 3.3±0.8 (2, 4) | 3±0.6 (2, 3) | 2.4±1 (1, 4) | 2.7±0.8 (2, 4) | 3±0.6 (2, 4) | 3.3±0.8 (2, 4) | 3.7±0.8 (3, 5) | 4±0.8 (3, 5) | 4.6±0.5 (4, 5) |

| Flumazenil | 5±0 (5, 5) | 4.9±0.4 (4, 5) | 4.3±1 (3, 5) | 3.9±0.9 (3, 5) | 3.3±0.5 (3, 4) | 3.6±1 (3, 5) | 3.3±1.3 (2, 5) | 2.6±0.5 (2, 3) | 2.4±0.8, (1, 3) | 3±0.6 (2, 4) | 3.1±0.7 (2, 4) | 3.7±1 (3, 5) | 4.4±0.8 (3, 5) |

Flumazenil or placebo administered immediately after 120 minute data collection point.

Flumazenil Clinical Effects

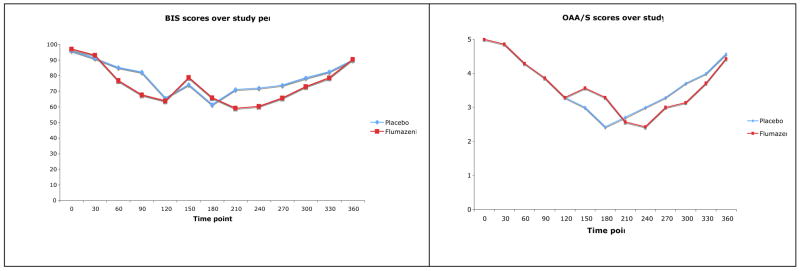

The SM injection of flumazenil and the placebo at 120 minutes resulted in a transient increase recorded at the 150 minute observation in the BIS score for both groups. Although the BIS score increased an average of 23 percent in the group receiving flumazenil compared to 14 percent in the group receiving the saline placebo, this difference was not significant (t=0.849, p=0.41). The increase was not sustained in either group more than a single 30 minute observation period as indicated by the BIS scores returning to a hypnotic state similar to where they were before the reversal intervention at 120 minutes. As the clinical effects of triazolam began to diminish, BIS scores for both groups began to return toward baseline levels. In comparison to the BIS data, OAA/S scores significantly increased in response to flumazenil at the 150 minute observation (t=2.19, p= 0.049), but were not sustained beyond a single 30 minute observation period. As seen with the BIS data, OAA/S scores for both groups were returning toward baseline levels as the 360-minute observation period approached (t= 0.078, p=0.94; t=0.397, p=0.70). By the end of the 240-minute post flumazenil observation period, all subjects were sufficiently recovered from their sedation to be discharged. Figure 1 graphically displays the mean BIS and OAA/S scores for both groups, and Table 2 describes the variability for each of the measures in terms of the standard deviation, minimum and maximum scores.

Figure 1.

Time-dependent changes in the BIS (A) and) OAA/S (B) scores.

At no time during the 360-minute observation period did any of the subjects display any premorbid changes that required intervention. Table 3 describes the time- and drug-dependent changes in the physiologic measures.

Table 3.

Time- and Drug-Dependent Changes in Vital Signs

| 0 min | 30 min | 60 min | 90 min | 120 mina | 150 min | 180 min | 210 min | 240 min | 270 min | 300 min | 330 min | 360 min | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic BP; mm Hg | |||||||||||||

| Placebo | 109±3 (105, 115) | 106±4 (103, 111) | 105±5 (100, 111) | 103±6 (93, 108) | 103±6 (95, 108) | 101±9 (87, 111) | 102±8 (92, 112) | 101±8 (87, 110) | 103±8 (88, 108) | 101±10 (84, 111) | 103±8 (92, 115) | 103±11 (81, 113) | 107±6 (99, 116) |

| Flumazenil | 121±11 (106, 134) | 113±15 (96, 134) | 109±13 (93, 128) | 109±12 (92, 129) | 106±12 (91, 126) | 109±11 (97, 127) | 109±15 (87, 127) | 112±10 (104, 127) | 109±6 (97, 116) | 113±14 (98, 132) | 103±10 (85, 115) | 113±16 (95, 138) | 116±16 (99, 138) |

| Diastolic BP; mm Hg | |||||||||||||

| Placebo | 66±7 (58, 78) | 61±6 (53, 69) | 61±6 (54, 70) | 58±5 (50, 64) | 61±5 (55, 70) | 56±4 (49, 60) | 58±7 (49, 67) | 55±5 (46, 61) | 54±7 (44, 63) | 58±7 (47, 64) | 56±6 (46, 61) | 59±8 (45, 70) | 61±9 (55, 81) |

| Flumazenil | 72±12 (61, 91) | 66±15 (48, 86) | 65±13 (48, 82) | 64±9 (57, 75) | 61±12 (48, 80) | 61±15 (43, 83) | 61±14 (44, 85) | 60±12 (45, 76) | 64±12 (50, 81) | 60±15 (45, 86) | 60±11 (48, 76) | 64±15 (44, 93) | 68±14 (55, 93) |

| Heart Rate; beats/min | |||||||||||||

| Placebo | 60±14 (41, 76) | 60±13 (41, 76) | 60±15 (41, 72) | 54±13 (41, 75) | 59±17 (46, 81) | 57±13 (43, 76) | 59±17 (41, 87) | 59±17 (41, 85) | 53±11 (41, 65) | 60±18 (43, 86) | 58±12 (44, 73) | 57±14 (43, 74) | 65±12 (52, 84) |

| Flumazenil | 70±10 (57, 85) | 66±7 (57, 77) | 63±6 (55, 70) | 65±6 (58, 75) | 63±4 (59, 69) | 65±7 (57, 76) | 67±11 (52, 84) | 65±10 (56, 78) | 62±12 (51, 81) | 67±9 (56, 81) | 64±13 (52, 88) | 64±11 (50, 81) | 73±14 (57, 96) |

| Resp. Rate; breaths/min | |||||||||||||

| Placebo | 16±2 (13, 17) | 15±2 (12, 18) | 16±2 (13, 16) | 15±1 (13, 17) | 16±2 (13, 17) | 16±2 (13, 17) | 16±2 (13, 19) | 16±2 (13, 18) | 16±2 (13, 19) | 16±2 (13, 19) | 16±2 (13, 18) | 17±2 (14, 19) | 16±2 (14, 19) |

| Flumazenil | 16±1 (15, 18) | 16±1 (14, 18) | 16±2 (13, 20) | 16±2 (12, 20) | 16±2 (14, 20) | 16±2 (14, 20) | 16±2 (14, 20) | 17±2 (15, 20) | 17±2 (15, 20) | 17±2 (14, 20) | 16±1 (14, 18) | 16±2 (14, 19) | 17±1 (15, 18) |

| Hb Sat.; percent | |||||||||||||

| Placebo | 99±1 (97, 100) | 99±2 (96, 100) | 99±1 (97, 100) | 99±1 (97, 100) | 99±1 (97, 100) | 99±1 (96, 100) | 99±1 (97, 100) | 99±1 (97, 100) | 99±1 (96, 100) | 99±2 (96, 100) | 99±1 (97, 100) | 99±1 (98, 100) | 99±1 (96, 100) |

| Flumazenil | 98±1 (96, 100) | 98±2 (96, 100) | 97±2 (95, 100) | 98±2 (95, 100) | 98±2 (96, 100) | 99±2 (97, 100) | 98±1 (96, 100) | 98±2 (95, 100) | 97±2 (95, 100) | 98±1 (97, 100) | 98±2 (95, 100) | 99±1 (98, 100) | 98±1 (97, 100) |

Flumazenil or placebo administered immediately after 120 minute data collection point.

Side effects

The intraoral injection site was inspected prior to discharge from the clinic and 24 hours afterwards. All intraoral tissues had returned to normal color and architecture by the time patients were discharged, and were also normal at the 24-hour post-sedation recall appointment. Study participants reported no adverse effects.

DISCUSSION

This randomized trial was conducted with U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval to evaluate the potential of a single intraoral injection of flumazenil as a rescue strategy for oversedation as a result of sequential oral dosing of triazolam. As a pilot under the IND permit, the number of participants and study design were limited. The incremental SL administration of triazolam is popular sedation technique for anxious patients. This is significant because the administration of triazolam in this way carries the ability to deliver total doses that are in excess of what is commonly accepted as the maximum recommended dose, thus increasing the risk of evoking unwanted side effects.16–18 Additionally, compared to the oral route of administration, SL administration of the same dose of triazolam in the dental setting has been reported to result in higher plasma concentrations of the sedative.12 Taken together, it is clear that safe and effective rescue strategies need to be available for the growing number of general dentists without advanced sedation training that are using incremental SL dosing of triazolam to sedate their patients.

The results demonstrate that moderate to deep sedation as a result of sequential SL dosing of triazolam is incompletely and transiently attenuated by a 0.2 mg SM injection of flumazenil in the posterior superior vestibule. A larger dose initially or by repeat injection might be have been more effective. While IV administration of flumazenil has been shown to have the latency of its peak effect occur within a few minutes, both our data suggest that the latency for SM administration is much longer.24 However, this does not negate the possibility that other CNS functions are being modulated by flumazenil with a shorter latency in response to SM administration. For example, a test of explicit learning (Modified Oxford Posttraumatic Scale, MOPTAS) two minutes post-flumazenil injection found 57 percent of those who received flumazenil versus 14 percent of those who received the saline placebo able to correctly recall a picture shown to them 24 hours later.31

This transient attenuation of sedation lasted no longer than a single 30-minute observation period, after which the sedative effects of the triazolam returned. Such a result was not completely unexpected. As a competitive receptor antagonist, flumazenil binds to the same site as the agonist, triazolam. The clinical duration of action for flumazenil is short compared to that of the benzodiazepines it would be used to reverse.32 Therefore, in situations in which the clinical duration of the benzodiazepine are substantially longer than that of flumazenil, rebound sedation is likely to occur. While the clinical duration of triazolam administered as a single dose is comparable to that of flumazenil, our previous research has shown that incremental dosing of this short-acting benzodiazepine results in long-lasting sedation that is dose-dependent.30,33

Because most general dentists using incremental SL dosing of triazolam to sedate their adult patients usually do not have advanced training in sedation4, rescue strategies need to be effective, easy to perform, and should optimally not require specialized instrumentation. The rescue technique of a single intraoral SM injection of 0.2 mg flumazenil in the maxillary posterior vestibule does not meet this challenge. It is an injection site that dentists are familiar with because of their routine administration of local anesthetic solutions in the posterior maxillary region, and the armamentarium is relatively simple (a 5 mL sterile disposable syringe and 25 gauge needle were used in this study). However, it is not completely effective and appears to have too slow a latency.

The sedation protocol was standardized and did not vary by any clinical criteria that might be used in practice (e.g., a stopping rule to limit the amount of triazolam administered). Moreover, no dental work was performed. This is significant because it is likely that the amount of CNS depression we observed might have been less in a clinical environment with stimulation (e.g., rotary handpieces, intraoral injections, etc.). This would especially be true in situations where the patient has high levels of dental fear. Nevertheless, our experimental conditions would be very similar to periods during treatment in which minimal or no stimulation is present (e.g., the period of time between the administration of local anesthesia and the beginning of the procedure, while films are been processed or during endodontic instrumentation).

Our preliminary results indicate that additional research is needed to evaluate rescue techniques that can be used by general dentists. This recommendation is consistent with the findings reported in the survey of members of the Organization for Conscious Sedation (DOCS).18 A rescue strategy must be evaluated in such a way as to demonstrate its safety and efficacy for all of the population, not just a narrowly tailored subset. As such, future study populations need to reflect the diversity of the population, making certain that there is adequate representation among racial and ethnic groups, age ranges, health status and sex at a minimum. The sample sizes of such studies would be substantially larger than permitted for the current initial study in humans under FDA guidance.

This report on the feasibility of an atypical pharmacologic rescue strategy underscores the importance of patient monitoring. The findings of the survey of DOCS members was reassuring in that those dentists responding employed pulse oximetry and automated blood pressure devices.18 Because flumazenil’s latency to effect even in the best case (IV administration) may be two to three minutes, BLS skills are essential to ensure adequate oxygenation.

Randomized clinical trials of sequential oral sedation techniques where dental treatment is provided are needed. Not only do these randomized clinical trials need to assess efficacy, they also need to examine safety and rescue strategies for the most likely of unwanted side effects. Only then can practice guidelines that are truly evidence-based be developed and strategies needed to provide care to populations in the U.S. with oral health disparities because of dental fear and anxiety be fully available. This research was supported, in part, by Grant No. T32DE007132 (Pickrell) from the NIDCR, NIH. Aspect Medical Systems (Newton, MA) provided materials and technical support for the BIS monitoring. Dr. Hosaka is Associate Professor at the Matsumoto Dental University, Shiojiri, Japan. He was Visiting Assistant Professor at the University of Washington in Seattle during the course of this study. During the period of this research, Dr. Jackson was Associate Professor in the Department of Oral Medicine at the University of Washington. He is currently Chief, Center for Diversity and Health Equity, Children’s Hospital and Regional Medical Center, Seattle. Dr. Pickrell is a Senior Fellow in the Department of Dental Public Health Sciences at the University of Washington. Dr. Heima is Acting Assistant Professor in the Department of Pediatric Dentistry at the University of Washington. Dr. Milgrom is Professor in the Department of Dental Public Health Sciences and the Dental Fears Research Clinic, University of Washington.

References

- 1.Smith TA, Heaton LJ. Fear of dental care: Are we making any progress? JADA. 2003;134:1101–8. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordon SM, Dionne RA, Snyder J. Dental fear and anxiety as a barrier to accessing oral health care among patients with special health care needs. Spec Care Dentist. 1998;18:88–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1998.tb00910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milgrom P, Weinstein P, Getz T. Treating Fearful Dental Patients. Seattle: University of Washington Continuing Dental Education; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dionne RA, Yagiela JA, Coté CJ, Donaldson M, Edwards M, Greenblatt DJ, Haas D, Malviya S, Milgrom P, Moore PA, Shampaine G, Silverman M, Williams RL, Wilson S. Balancing efficacy and safety in the use of oral sedation in dental outpatients. JADA. 2006 Apr;137(4):502–13. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young ER, Mason D. Triazolam an oral sedative for the dental practice. J Can Dent Assoc. 1988;54:511–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bixler EO, Kales A, Manfredi RL, Vgontzas AN. Triazolam and memory loss. Lancet. 1991;338:1391–2. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weingartner HJ, Hommer D, Lister RG, Thompson K, Wolkowitz O. Selective effects of triazolam on memory. Psychopharmacol. 1992;106:341–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02245415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quarnstrom FC, Milgrom P, Moore PA. Experience with triazolam in preschool children. Anesth Pain Control Dent. 1992;1:157–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berthold CW, Schneider A, Dionne RA. Using triazolam to reduce dental anxiety. JADA. 1993;124:58–64. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1993.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stopperich PS, Moore PA, Finder RL, McGirl BE, Weyant RJ. Oral triazolam pretreatment for intravenous sedation. Anesth Prog. 1993;40:117–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Milgrom P, Quarnstrom FC, Longley A, Libed E. The efficacy and memory effects of oral triazolam premedication in highly anxious dental patients. Anesth Prog. 1994;41:70–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berthold CW, Dionne RA, Corey SE. Comparison of sublingually and orally adminisered triazolam for premedication before oral surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endodont. 1997;84(2):119–24. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coldwell SE, Awamura K, Milgrom P, Depner KS, Kaufman E, Preston KL, Karl HW. Side effects of triazolam in children. Pediatr Dent. 1999;21:18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matear DW, Clarke D. Considerations for the use of oral sedation in the institutionalized geriatric patient during dental interventions: a review of the literature. Spec Care Dentist. 1999;19:56–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1999.tb01369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raadal M, Kaako T, Coldwell SE, Milgrom P, Weinstein P, Perkis V, Karl HW. A randomized clinical trial of triazolam in 3– to 5– year-olds. J Dent Res. 1999;78:1197–203. doi: 10.1177/00220345990780060201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson DL, Johnson BS. Inhalational and enteral conscious sedation for the adult dental patient. Dent Clin N Am. 2002;46:781–802. doi: 10.1016/s0011-8532(02)00029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Triazolam. [Accessed November 16, 2008];Facts & Comparisons 4.0. 2004 March; URL: http://online.factsandcomparisons.com.offcampus.lib.washington.edu/MonoDisp.aspx?monoID=fandc-hcp12124&inProdGen=true&quick=triazolam&search=triazolam.

- 18.Gordon SM, Shimizu N, Shlash D, Dionne RA. Evidence of safety for individualized dosing of enteral sedation. Gen Dent. 2007 Sep-Oct;55(5):410–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooper SA, Quinn PD, MacAfee K, McKenna D. Reversing intravenous sedation with flumazenil. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;72(1):2–9. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(91)90179-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scheepers LD, Montgomery CJ, Kinahan AM, Dunn GS, Bourne RA, McCormack JP. Plasma concentration of flumazenil following intranasal administration in children. Can J Anaesth. 2000 Feb;47(2):120–4. doi: 10.1007/BF03018846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haret D. Rectal flumazenil can save the day. Paediatr Anaesth. 2008 Apr;18(4):352. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2008.02476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palmer RB, Mautz DS, Cox K, Kharasch ED. Endotracheal flumazenil: a new route of administration for benzodiazepine antagonism. Am J Emerg Med. 1998 Mar;16(2):170–2. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(98)90039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oliver FM, Sweatman TW, Unkel JH, Kahn MA, Randolph MM, Arheart KL, Mandrell TD. Comparative pharmacokinetics of submucosal vs. intravenous flumazenil (Romazicon®) in an animal model. Pediatr Dent. 2000;22:489–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hosaka K, Jackson DL, Pickrell JE, Heima M, Milgrom P. Triazolam reversal by a single intraoral fixed-dose of submucosal flumazenil. Abstract 1267. International Association of Dental Research Annual Meeting; July 3; Toronto; 2008. [Accessed August 9, 2008]. URL: http://iadr.confex.com/iadr/2008Toronto/techprogram/abstract_105562.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chernik DA, Gillings D, Laine H, et al. Validity and reliability of the Observer’s Assessment of Alertness/Sedation Scale: study with intravenous midazolam. J Clin Psychopharm. 1990;10:244–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu J, Singh H, White PF. Electroencephalogram bispectral analysis predicts the depth of midazolam-induced sedation. Anesthesiol. 1996;84:64–9. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosow C, Manberg PJ. Bispectral index monitoring. Anesthesiol Clin N Am. 2001;19:947–66. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8537(01)80018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glass PS, Bloom M, Kearse L, et al. Bispectral analysis measures sedation and memory effects of propofol, midazolam, isoflurane, and alfentanil in healthy volunteers. Anesthesiol. 1997;86:836–47. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199704000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sandler NA, Sparks BS. The use of bispectral analysis in patients undergoing intravenous sedation for third molar extractions. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58:364–8. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(00)90911-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jackson DL, Milgrom P, Heacox GA, Kharasch E. Pharmacokinetics and clinical effects of multi-dose sublingual triazolam in healthy volunteers. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006 Feb;26(1):4–8. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000186742.07148.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pickrell JE, Hosaka K, Heima M, Jackson DL, Milgrom P. The effects of stacked triazolam dosing on memory and suggestibility. Abstract 2427. International Association of Dental Research Annual Meeting; March 24; New Orleans. 2007. [Accessed August 9, 2008]. URL: http://iadr.confex.com/iadr/2007orleans/techprogram/abstract_90745.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Charney DS, Mihic SJ, Harris RA. Hypnotics and Sedatives. In: Hardman JG, Limbird LE, Gilman AG, editors. Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 10. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hosaka K, Jackson DL, Pickrell JE, Heima H, Milgrom P. The sedative effect of stacked dosing of triazolam. Abstract 553. International Association for Dental Research Annual Meeting; March 22; Toronto. 2007. [Accessed August 9, 2008]. URL: http://iadr.confex.com/iadr/2007orleans/techprogram/abstract_87989.htm. [Google Scholar]