Abstract

This study examines longitudinal associations between adolescent adjustment and perceived parental support across the middle-school years (ages 11 to 13) in a diverse sample of 197 girls and 116 boys. Growth curve models revealed associations between the slope of change in perceptions of support in relationships with mothers and fathers and the slope of change in adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptoms such that declining support accompanied increasing problems. After controlling for this correlated change, there was still evidence of child-problem effects on changes in relationship support (i.e., initial levels of adolescent externalizing symptoms predicted subsequent changes in perceived parental support), but there was no evidence of parent-support effects on changes in adjustment (i.e., initial levels of relationship support did not predict changes in adolescent externalizing symptoms). Declines in perceived parental support were steeper at high-initial levels of adolescent externalizing than at average or low levels.

Keywords: parent–adolescent relationships, growth modeling, relationship quality

Close relationships are crucial indicators of adjustment across the lifespan, and the adolescent years are no exception. Many studies have described concurrent associations between the quality of relationships with parents and adolescent adjustment, but less is known about their interplay over time (see Collins & Steinberg, 2006, for review). Do behavior problems forecast deteriorating relationships? Does a lack of relationship support forecast escalating adjustment difficulties? Evidence of both suggests a bidirectional process, whereas one without the other suggests unidirectional influences that signal child-driven or parent-driven effects. Complicating matters, adjustment trajectories and relationship support trajectories overlap considerably, yet models of influence rarely account for the contributions of joint changes, which are represented by correlations between slopes (Kuczynski, 2003). The present study employs growth curve modeling to disentangle bidirectional and unidirectional longitudinal influences from correlated trajectories of change using three waves of data on adolescent adjustment and perceived support in relationships with mothers and fathers.

Both negative and positive features of parent–child relationships have been implicated in adolescent adjustment. These are not simply two sides of the same coin; hostility and affection can go hand in hand, and so can the absence of each, which helps to explain why studies report weak associations between positive and negative provisions of parent–child relationships (e.g., Adams & Laursen, 2007; Furman & Buhrmester, 1992). Much is known about the adjustment correlates of high family negativity. Chronic hostility fosters youth difficulties and troubled youth behave in ways that tend to elicit antagonism from parents (Laursen & Hafen, in press). Less is known about the correlates of low relationship support. Concurrent data suggests that parent support is inversely related to adjustment outcomes (Collins, Maccoby, Steinberg, Hetherington, & Bornstein, 2000), but longitudinal pathways have yet to be specified. The present study concerns the adjustment correlates of positive features of parent–child relationships. We focus on perceived parental support, as measured by the Network of Relationships Inventory (Furman & Buhrmester, 1985), a well-validated metric of relationship quality. Perceived support encompasses a variety of provisions that the parent and the parent–child relationship provide to the adolescent, in domains ranging from instrumental assistance, companionship, and reliable alliance to intimacy, affection, and nurturance. Because low perceived support assumes minimal involvement by parents in the lives of children, it should be linked to adolescent conduct problems; because low perceived support assumes a lack of parental affection, it should also be associated with adolescent depression (Barber, Stoltz, & Olsen, 2005).

Conceptual models of parent–child influence typically fall into one of four camps (Collins, 2002). In parent-driven models, the child's well-being is presumed to be a product of parent socialization. Parental support may provide a buffer against stressful life circumstances, creating an environment that promotes constructive coping rather than disruptive behavior (Windle, 1992). A lack of support from parents may foster low self-worth, which is often a prelude to internalizing difficulties (Laursen, Furman, & Mooney, 2006). In the present study, parent-support effects describe the extent to which perceived support in mother–child and father–child relationships predicts subsequent changes in adolescent adjustment. In child-driven models, parenting is presumed to be a reaction to the child's conduct. Some have hypothesized that parents withdraw from difficult youth, which may elevate the child's susceptibility to adverse peer influences, particularly during the early adolescent years when peer pressures are greatest (Kerr, Stattin, & Pakalniskiene, 2008). Parents may also withdraw from depressed youth for the same reasons that spouses and friends limit interactions with those suffering from internalizing disorders (Larson, Raffaelli, Richards, Ham, & Jewell, 1990). A withdrawal of support could exacerbate anxiety and isolation, hastening a descent into depression. In the present study, child-problem effects describe the extent to which adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptoms predict subsequent changes in perceived parental support.

Bidirectional models assume that parent effects and child effects operate in tandem. In the present study, reciprocal parent-support effects and child-problem effects describe joint patterns of parent influence on subsequent child adjustment and child influence on subsequent parent caregiving. Correlated change models describe overlapping trajectories of change in parents and children that may inflate estimates of influence in parent-driven and child-driven models. Correlated changes may be the result of shared environmental or genetic factors or they may reflect micro-analytic interaction processes in which the agent of influence cannot be distinguished from the recipient. In the present study, correlations between child problem slopes and parent support slopes are partitioned from parent-support effects and child-problem effects to provide a more accurate estimate of unidirectional and bidirectional influences.

Parent-driven models dominate research on family relationships during adolescence (Laursen & Collins, in press). There are several good reasons to question this bias. First, time spent with parents declines across early and midadolescence, accompanied by a similar decrease in mutual expressions of affection (Larson, Richards, Moneta, Holmbeck, & Duckett, 1996). Second, young adolescents seek to gain authority over domains that were once subordinated to parents, especially in areas that concern the regulation of personal behavior (Smetana, 1988). Third, peer oriented norm-breaking and substance use rise rapidly in many cultures as adolescents seek the appearance of adult status and maturity (Moffitt, 1993); this coincides with changes in the academic structure during middle school that diminish the significance of contacts with teachers and increase those with age mates. Finally, pubertal maturation often drives down self-worth, elevating the risk for depression and anxiety, particularly among girls (Susman & Rogol, 2004). Thus, the middle-school years are noteworthy for developmental milestones that should enhance child-problem effects and reduce parent-support effects.

The literature on parental monitoring and adolescent behavior problems illustrates the pitfalls that confront scholars of parent–child influence. Research conclusions tend to be a function of the type of model tested. Parent-driven models indicate that parental monitoring reduces later problem behavior (e.g., Pettit, Bates, Dodge, & Meece, 1999), whereas child-driven models indicate that monitoring declines in response to youth behavior problems (e.g., Simons, Chao, Conger, & Elder, 2001). The much smaller longitudinal literature on parent support and adolescent adjustment suffers from similar limitations. Parent-driven models indicate that high levels of parental support predicted declines in adolescent depressive symptoms and decreased the odds that adolescents would follow an elevated depression trajectory (Brendgen, Wanner, Morin, & Vitaro, 2005; Deković, Buist, & Reitz, 2004), although these associations tend to disappear when other parenting variables are simultaneously considered (Rogers, Buchanan, & Winchell, 2003). Not all of these studies examined externalizing, but there was no evidence that support predicted changes in externalizing among those that did. Bidirectional models indicate that adolescent reports of externalizing symptoms predict subsequent adolescent perceptions of parental support, but initial parent support does not predict externalizing symptoms 1 year later (Huh, Tristan, Wade, & Stice, 2006; Stice & Barrera, 1995). Unfortunately, the latter findings were not replicated when parent reports of adolescent externalizing symptoms replaced adolescent reports, raising the prospect of artifactual results driven by shared-reporter variance. In each case, estimates of effects were inflated by correlations between the slopes of support and the slopes of adjustment, an essential omission in light of recent reports that changes in child well-being are strongly associated with concurrent changes in the perceived quality of parent-child relationships (Galambos, Barker, & Krahn, 2006; Videon, 2005).

The present investigation examines change across the middle-school or early adolescent years. Growth curve analyses identify concurrent and prospective associations between indexes of adolescent adjustment and perceptions of support in relationships with mothers and fathers. Child-driven and parent-driven models are tested simultaneously. To explore child-problem effects, analyses examine over-time associations from adolescent externalizing and internalizing symptoms in the sixth grade to changes in perceived support from mothers and fathers across the sixth to eight grades, testing the hypothesis that higher initial adjustment problems are associated with declines in parental support. To explore parent-support effects, analyses examine over-time associations from perceived maternal and paternal support in the sixth grade to changes in adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptoms across the sixth to eight grades, testing the hypothesis that lower initial support should be associated with increases in adjustment problems. These hypotheses are not mutually exclusive: Evidence for both suggests bidirectional effects. Correlations between the trajectory of change in parent support and the trajectory of change in adolescent adjustment are identified and uniquely apportioned, so that overlapping slopes do not inflate estimates of influence. There is good reason to suspect that links between relationship quality and adolescent maladjustment may be strongest among dysfunctional families and troubled youth (e.g., Laursen & Collins, in press), so supplemental analyses test the hypothesis that child-driven decreases in support are limited to families with poorly adjusted youth and that parent-driven increases in youth maladjustment are limited to families that proffer minimal support.

Method

Participants

Participants included 313 students (197 females, 116 males) from public middle schools in the greater Miami and Fort Lauderdale area. Three annual waves of data were collected, starting when participants were 11 or 12 years old (M = 11.59, SD = .55). Approximately 36% of the sample was European American (n = 113), 26% was African American (n = 81), and 38% was Hispanic American (n = 119). At the outset of the study, 56.9% of participants lived with both biological parents (n = 178), 24.3% lived with a single parent (n = 76), 13.7% lived with a biological parent and a step-parent (n = 43), and 5.1% did not provide household structure information (n =16). Reports of parental education and occupation, available for 287 households, were used to assess socioeconomic status (Hollingshead, 1975). The scale has a potential range of 8 to 66; scores for participants ranged from 11 to 66 (M = 38.54, SD = 9.91).

Instruments

Adolescents completed the same measures of adjustment problems and perceived support in the sixth, seventh, and eight grades. Mothers completed similar instruments at the outset of the study, when the child was in the sixth grade.

Perceived support

Adolescents and mothers completed the 33-item Network of Relationships Inventory (Furman & Buhrmester, 1985). Items were rated on a scale ranging from 1 (little or none) to 5 (the most). These subscales load on three distinct factors (Adams & Laursen, 2007; Furman, 1996): relationship support, negativity, and relative power. The present study concerns perceived support, which includes 24 items that describe admiration, affection, companionship, instrumental aid, intimacy, nurturance, reliable alliance, and satisfaction (e.g. “How much does this person help you figure out or fix things?”). Adolescents separately rated relationships with mothers and fathers. Mothers rated relationships with children on items that reflected support provided by mothers to children. Item scores were averaged to create separate scores for adolescent reports of support in mother-child relationships and father-child relationships at each grade, and for maternal reports of support in mother-child relationships in the sixth grade.

Adolescent adjustment

Adolescents completed the Youth Self-Report and mothers completed the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1991). Items were rated on a scale ranging from 0 (not true) to 2 (very true or often true). Two broadband indexes of adjustment were constructed from narrowband scales. Externalizing symptoms include 30 to 33 items that measure aggressive behavior and delinquent behavior (e.g., “gets in many fights”). Internalizing symptoms includes 32 items that measure anxiety/depression, somatic complaints, and withdrawn behaviors (e.g., “unhappy, sad, or depressed”). Raw scores were summed for each broadband index. Across grades, 14% to 18% of the sample scored at clinical or borderline clinical levels of externalizing, and 7% to 8% of the sample scored at clinical or borderline levels of internalizing.

Procedure

Participants were recruited from classes during school hours. Research teams answered questions and distributed parental consent forms and demographic surveys. Participation rates mirrored those of previous studies (e.g., Silk, Steinberg, & Morris, 2003), ranging from approximately 45% to 75% within schools. Surveys were administered at annual intervals to small groups of students in quiet school settings in sessions that lasted approximately 1 hr. Research assistants read the instructions out loud and supervised the completion of the questionnaires. A total of 313 adolescents completed questionnaires in the sixth grade. Of this total, 37 did not participate in the seventh grade and an additional 20 dropped out in the eight grade, yielding an overall retention rate of 81.8% (n = 256). Due to the advantages of latent growth curve modeling and maximum likelihood estimation, those individuals who dropped out of the study can still be analyzed. Analyses were run separately including those participants who dropped out in either the seventh or eight grade and for only those with three complete waves of data; the pattern of results remained consistent, thus discussion of the analyses includes all 313 participants.

Plan of Analysis

Growth curve modeling examined associations between adolescent adjustment and perceived support, using a structural equation modeling framework with AMOS 7.0 (Arbuckle, 2006). Intra-individual change was modeled with factor loadings at each time point, estimating the latent factors of the intercept (mean levels) and the slope (change over time) for each variable. Results are described in terms of unstandardized beta weights. Analyses that included both internalizing symptoms and externalizing symptoms provided a poor fit to data on maternal support, χ2(7, N = 313) = 34.37, p < .001, comparative fit index (CFI) = .88, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .14 and paternal support, χ2(7, N = 313) = 35.87, p < .001, CFI = .88, RMSEA = .15. As a consequence, four separate analyses were conducted in which externalizing symptoms and internalizing symptoms were separately paired with perceived maternal support and perceived paternal support. These models initially included associations between intercepts, between slopes, between the intercept of adolescent reported adjustment problems and slope of adolescent perceptions of parental support, and between the intercept of adolescent perceptions of parental support and the slope of adolescent reports of adjustment problems. Intercept loadings were set at 1 and slope loadings were set at fixed intervals (0, 2, and 4). Intercepts and slopes were allowed to covary. Curvilinear slopes could not be considered with three time points. If the fully saturated model fit the data poorly, nonsignificant paths were omitted to improve the fit.

To address concerns about shared reporter variance, additional analyses were conducted with Grade 6 mother reports. Each included intercept to intercept paths and intercept to slope paths but not slope to slope paths. In the first set, four separate analyses were conducted in which mother reports of initial adolescent externalizing symptoms and internalizing symptoms were separately paired with adolescent reports of maternal support and paternal support. In the second set, two separate analyses were conducted in which mother reports of initial maternal support were separately paired with adolescent reports of externalizing symptoms and internalizing symptoms.

Statistically significant intercept to slope associations were followed with analyses to estimate the slope of the outcome variable at different initial levels of the predictor variable (Preacher, Curran, & Bauer, 2006). Simple slopes for outcome variables were estimated at high (1 SD above the mean), medium (the mean), and low (1 SD below the mean) conditional intercept values.

To test for possible demographic differences in the intercept or slope, manifest variables of sex, ethnicity, and household structure were added to each of the models. Results revealed evidence of intercept sex differences for both internalizing and externalizing symptoms. There were no demographic differences relating to slope. To eliminate any possible influence of sex on our analyses, T scores were used instead of raw scores in every analysis.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 describes correlations between variables for those participants who provided three waves of data. Concurrent associations linked parent support to externalizing symptoms and internalizing symptoms. Grade 6 self- and maternal reported externalizing symptoms were linked to Grades 7 and 8 support, but Grade 6 self- and maternal reported support were not linked to Grades 7 and 8 externalizing symptoms. There was little evidence of over-time links between internalizing symptoms and parent support.

Table 1.

Intercorrelations, Means, Standard Deviations, and Internal Reliabilities

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | M | SD | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sixth-grade mother reports | |||||||||||||||||

| 1. Externalizing | — | 7.86 | 6.99 | .82 | |||||||||||||

| 2. Internalizing | .48** | — | 7.09 | 5.23 | .80 | ||||||||||||

| 3. Support | −.38** | −.26* | — | 4.15 | 0.62 | .88 | |||||||||||

| Sixth-grade child reports | |||||||||||||||||

| 4. Externalizing | .26* | .14 | −.03 | — | 11.51 | 7.41 | .84 | ||||||||||

| 5. Internalizing | −.01 | .25* | −.04 | .61* | — | 11.42 | 7.67 | .78 | |||||||||

| 6. Maternal support | −.28* | −.23* | .46* | −.28* | −.18* | — | 4.33 | 0.74 | .92 | ||||||||

| 7. Paternal support | −.26* | −.20* | .40* | −.29* | −.20* | .51* | — | 4.23 | 0.71 | .90 | |||||||

| Seventh-grade child reports | |||||||||||||||||

| 8. Externalizing | .20* | .11 | .03 | .62* | .41* | −.10 | −.12 | — | 16.89 | 7.53 | .82 | ||||||

| 9. Internalizing | .03 | .30* | .04 | .43* | .63* | .13 | −.14 | .60* | — | 13.04 | 7.59 | .80 | |||||

| 10. Maternal support | −.24* | −.13 | .44* | .−17* | −.10 | .67* | .48* | −.20* | −.14 | — | 4.03 | 0.78 | .89 | ||||

| 11. Paternal support | −.22* | −.15 | .38* | −.21* | −.11 | .56* | .63* | −.24* | −.12 | .52* | — | 4.11 | 0.82 | .91 | |||

| Eighth-grade child reports | |||||||||||||||||

| 12. Externalizing | .19* | .12 | .02 | .52* | .31* | −.04 | −.08 | .58* | .37* | −.14 | −.16* | — | 18.60 | 7.88 | .85 | ||

| 13. Internalizing | .04 | .32* | .08 | .31* | .48* | −.06 | −.10 | .37* | .57* | −.07 | −.10 | .61* | — | 14.90 | 7.34 | .79 | |

| 14. Maternal support | −.19* | −.16* | .30* | −.20* | −.16* | .52* | .40* | −.22* | −.11 | −.63* | .52* | −.17* | −.17* | — | 3.97 | 0.85 | .91 |

| 15. Paternal support | −.24* | −.19* | .27* | .−25* | −.15* | .43* | .55* | −.27* | −.17* | .38* | .49 | −.20* | −.19* | .36* | 4.01 | 0.91 | .86 |

Note. n = 256 for child reports; n = 251 for mother reports. Externalizing raw scores had a potential range of 0 to 66 (child reports) and 0 to 60 (mother reports); actual scores ranged from 0 to 56 and 0 to 59, respectively. Internalizing raw scores had a potential range of 0 to 64; actual scores ranged from 0 to 49 (self-reports) and 0 to 50 (maternal reports). The social support scale ranged from 1 (little or none) to 5 (the most).

p < .01.

Growth Curve Statistics

Table 2 describes means and variances for the intercept and slope parameters for the four models that involved three waves of adolescent report data on adjustment problems and parental support. Models with maternal reports as predictor variables yielded the same linear slope results for adolescent report data. The linear slope results indicate that externalizing symptoms and internalizing symptoms increased over time and that perceived maternal and paternal support decreased. Table 1 presents means and standard deviations for each variable at each grade.

Table 2.

Growth Curve Statistics for Models With Three Waves of Adolescent Reports on Adjustment Problems and Parent Support

| Variable | Intercept | Linear slope | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | Variance | M | Variance | |

| Externalizing symptoms | 13.22* | 0.56* | 0.39* | 0.14* |

| Internalizing symptoms | 10.81* | 0.51* | 0.16* | 0.05 |

| Maternal support | 4.44* | 0.18* | −0.13* | 0.08* |

| Paternal support | 4.16* | 0.33* | −0.15* | 0.09* |

Note. N = 313.

p < .01.

Growth Curve Models for Externalizing Symptoms and Perceived Social Support

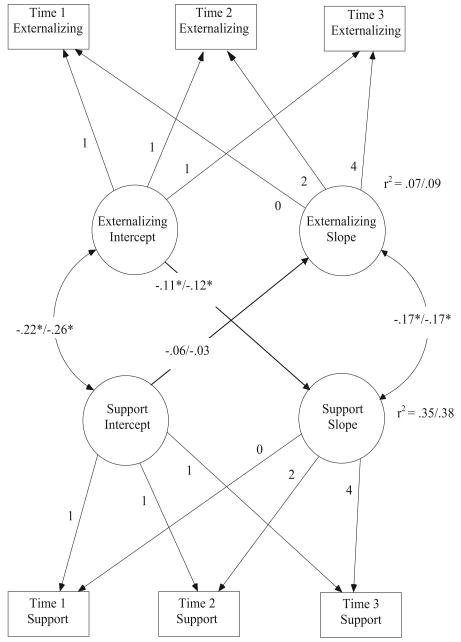

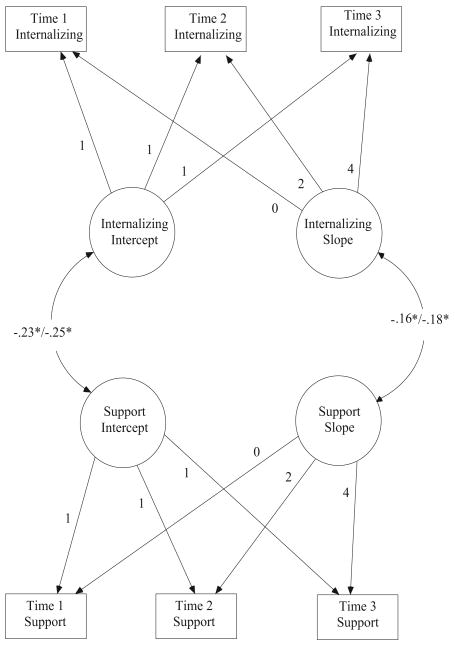

Figure 1 describes a model with three waves of adolescent reports on externalizing symptoms and perceived maternal support and a model with three waves of adolescent reports on externalizing symptoms and perceived paternal support. Both models fit the data, maternal support: χ2(7, N = 313) = 14.31, p = .05, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .05; paternal support: χ2(7, N = 313) = 15.77, p = .03, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .05. A similar pattern of results emerged. The intercept of externalizing symptoms was associated with the intercept of perceived support; higher initial levels of one were correlated with lower initial levels of the other. The slope of externalizing symptoms was associated with the slope of perceived support; increases in externalizing symptoms were linked with concurrent declines in perceived support. Finally, the intercept of externalizing symptoms was associated with the slope of perceived support; higher levels of externalizing symptoms in the sixth grade predicted greater decreases in perceived support from sixth grade to eight grade. The intercept of perceived support did not predict the slope of externalizing symptoms. Follow-up chi-square difference tests indicated that the two intercept to slope paths were significantly different from one another.

Figure 1.

Growth curve models with three waves of adolescent reports on externalizing symptoms and maternal support/paternal support.

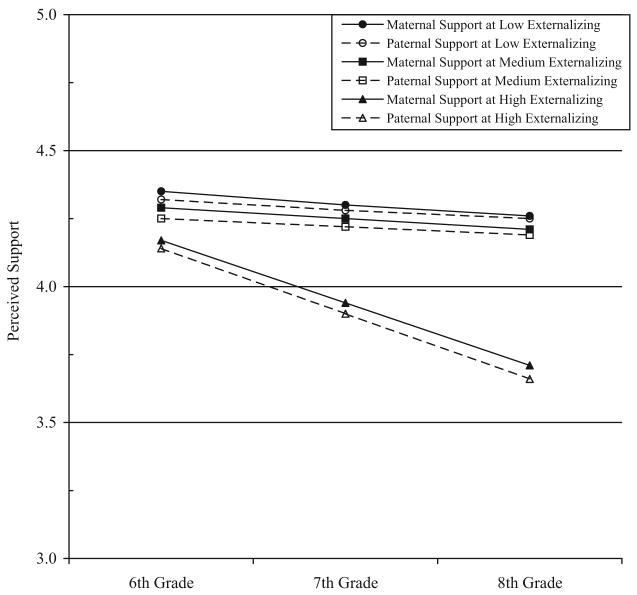

Figure 2 illustrates the results of follow-up analyses. The slope of change in maternal support and the slope of change in paternal support were both statistically significant (p < .05) when initial adolescent reports of externalizing were high (maternal support slope = −0.28; paternal support slope = −0.29), but not when initial adolescent reports of externalizing were medium (maternal support slope = −0.05; paternal support slope = −0.06) or low (maternal support slope = −0.03; paternal support slope = −0.05).

Figure 2.

Estimated change from sixth to eigth grade in adolescent reports of maternal and paternal support at low, medium, and high levels of sixth-grade adolescent self-reports of externalizing symptoms.

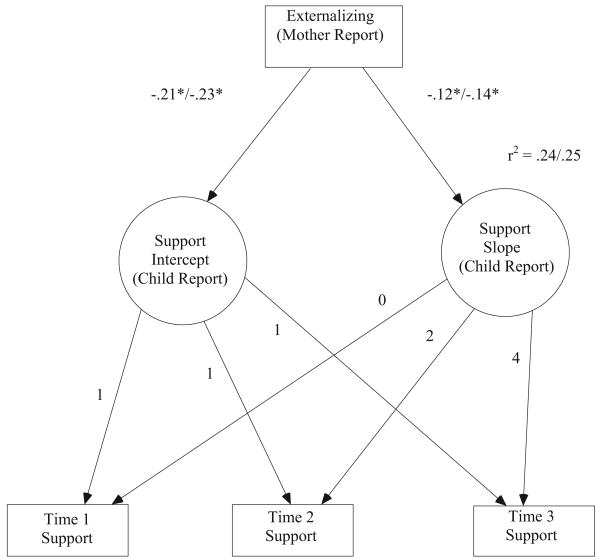

Three additional models were run with maternal reports at Grade 6 as the predictor variable. The first model included one wave of maternal reports on adolescent externalizing symptoms and three waves of adolescent reports on maternal support. The model fit the data, χ2(7, N = 279) = 19.64, p = .009, CFI = .95, RMSEA = .06. The second model included one wave of maternal reports on adolescent externalizing symptoms and three waves of adolescent reports on paternal support. The model fit the data, χ2(7, N = 279) = 20.23, p < .008, CFI = .94, RMSEA = .07. Figure 3 depicts the results of these two models. Maternal reports of adolescent externalizing symptoms at Grade 6 were associated with both the intercept and the slope of adolescent reports of maternal support and paternal support. The third model included one wave of maternal reports on maternal support and three waves of adolescent reports on externalizing symptoms. The model fit the data poorly, χ2(7, N = 279) = 27.22, p < .001, CFI = .90, RMSEA = .12.

Figure 3.

Growth curve model with one wave of maternal reports on adolescent externalizing symptoms and three waves of adolescent reports on maternal support/paternal support.

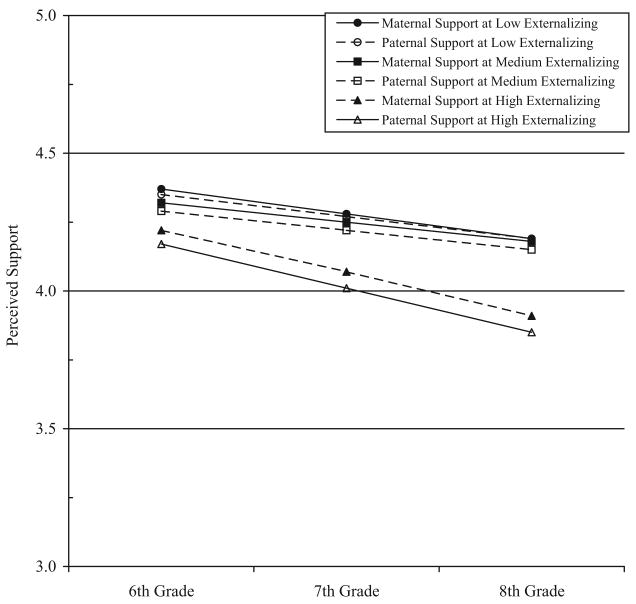

Figure 4 illustrates the results of follow-up analyses. The slope of change in maternal support and the slope of change in paternal support were both statistically significant (p < .05) when initial maternal reports of adolescent externalizing symptoms were high (maternal support slope = −0.25; paternal support slope = −0.23), but not when initial maternal reports of adolescent externalizing symptoms were medium (maternal support slope = −0.07; paternal support slope = −0.07) or low (maternal support slope = −0.06; paternal support slope = −0.04).

Figure 4.

Estimated change from sixth to eighth grade in adolescent reports of maternal and paternal support at low, medium, and high levels of sixth-grade maternal reports of adolescent externalizing symptoms.

Growth Curve Models for Internalizing Symptoms and Social Support

Fully saturated models for internalizing symptoms and maternal support did not fit the data, χ2(7, N = 313) = 34.91, p < .001, CFI = .89, RMSEA = .12; neither did fully saturated models for internalizing symptoms and paternal support, χ2(7, N = 313) = 38.05, p < .001, CFI = .88, RMSEA = .14. After nonsignificant intercept to slope paths were omitted, the fit of both models improved but was still poor, maternal support: χ2(7, N = 313) = 23.66 p = .002, CFI = .93, RMSEA = .09; paternal support: χ2(7, N = 313) = 25.83, p < .001, CFI = .92, RMSEA = .09. Figure 5 indicates a similar pattern of results for the final model for maternal support and the final model for paternal support. The intercept of internalizing symptoms was associated with the intercept of perceived support; higher initial levels of one were correlated with lower initial levels of the other. The slope of internalizing symptoms was associated with the slope of perceived support; increases in internalizing symptoms were linked with concurrent declines in perceived support.

Figure 5.

Growth curve models with three waves of adolescent reports on internalizing symptoms and maternal support/paternal support.

Three additional models were conducted using maternal reports at Grade 6 as the predictor variable. The first model included one wave of maternal reports of adolescent internalizing symptoms and three waves of adolescent reports of maternal support. The model did not fit the data, χ2(7, N = 278) = 29.61, p < .001, CFI = .89, RMSEA = .13. The second model included one wave of maternal reports of adolescent internalizing symptoms and three waves of adolescent reports of paternal support. The model did not fit the data, χ2(7, N = 278) = 39.94, p < .001, CFI = .86, RMSEA = .17. The third model included one wave of maternal reports of maternal support and three waves of adolescent reports of internalizing symptoms. The model did not fit the data, χ2(7, N = 278) = 28.11, p < .001, CFI = .90, RMSEA = .11.

Discussion

Growth curve models identified associations between adjustment problems and perceived parental support across the early adolescent years. There were strong associations between the slopes of internalizing and externalizing symptoms and the slopes of maternal and paternal support such that changes in adjustment problems accompanied changes in parent support. In addition, initial levels of mother and child reports of adolescent externalizing symptoms predicted subsequent changes in perceived support from mothers and fathers, but mother and child reports of parent support did not predict changes in adolescent externalizing. These findings suggest that child problems drive changes in the quality of parent–adolescent relationships but that parent support does not drive changes in early adolescent behavior problems.

There was considerable overlap between trajectories of change in parent–child relationship support and trajectories of change in adolescent adjustment. Declines in relationship support were accompanied by similar declines in adolescent adjustment. Findings of correlated change, novel to this study, have important implications for the conceptualization and operationalization of parent–child influence. In terms of understanding family relationships, the findings raise the prospect of synchronous change predicated on circular or interdependent mechanisms (Kuczynski, 2003). Alternatively, associations may have origins in common genetic variance. Either way, the findings suggest that previous studies probably overestimated unidirectional influences because child-driven and parent-driven effects were inflated by correlated patterns of change. To illustrate the need to account for correlated change, additional analyses were conducted in which slope-to-slope paths were omitted. We found that the overall fit of the model declined substantially and the amount of variance in the slope of support accounted for by the intercept of internalizing symptoms and externalizing symptoms increased by at least 5%. Such findings demonstrate the advantages that growth curve modeling holds over the analytic techniques typically employed in research on family influence (i.e., two-wave regression and path analyses).

After accounting for these correlated changes, child-driven effects remained for externalizing symptoms such that more initial behavior problems predicted greater subsequent declines in perceived maternal and paternal support. In contrast, initial relationship support did not predict subsequent changes in externalizing symptoms, suggesting that parent–child relationship quality during early adolescence is more sensitive to variations in child well-being than the reverse, a findings consistent with studies reporting that parents withdraw and disengage from relationships with troubled youth (e.g., Dishion, Nelson, & Bullock, 2004). We found the greatest declines in relationship support at the highest levels of initial behavior problems, with few changes in support when behavior problems were at or below the mean. In a recent review of the literature, Laursen and Collins (in press) concluded that most families do not experience significant relationship disruptions when children enter adolescence, with the notable exception of those who begin this period of transition handicapped by maladjustment or dysfunctional relationships. Findings from the present study are consistent with this assertion. Our results should give hope to parents with well-adjusted children, and serve as a warning to those parents with poorly adjusted children because they suggest that the efficacy of interventions that target family relationships may be limited in the face of intractable behavior problems.

Longitudinal data are a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for establishing causal relations between variables (Rutter, 1994). Longitudinal data help to sort out the order of effects in time. In the present study, the findings established a temporal sequence from adolescent externalizing problems at the start of middle school to subsequent changes in maternal and paternal support across the middle-school years, discounting reverse order effects from initial parent support to later adolescent behavior problems. Longitudinal data also help to establish a dose-response relation between predictor and outcome variables. In the present study, adolescent behavior problems predicted deteriorating relationships with parents, but only when adjustment difficulties reached a certain threshold; supplemental analyses revealed that the slope of decline was particularly strong when initial externalizing symptoms approached borderline clinical levels. These findings are important because they suggest that for most families with well-adjusted children, normative dabbling in minor deviance at the outset of adolescence does not lead to changes in perceived support from parents.

Despite these strengths, the study falls short of demonstrating causality. First, participants were not randomly (or quasi-randomly) assigned to conditions (Rutter, Pickles, Murray, & Eaves, 2001). The absence of randomization leaves the door open to alternative influence agents and pathways. Put simply the findings are consistent with the notion that high levels of externalizing problems cause declines in parent support across early adolescence, but proof must await replication with a natural experiment and a genetically informed design that rules out the contributions of other predictors. Second, contrary to our hypothesis, initial internalizing symptoms failed to predict the slope of subsequent parent support. We will not offer a post-hoc conceptual rationale of symptom-specific effects because we think the results reflect differences in the magnitude and not the mechanisms of influence. There was little change over the course of the study in most variables, which means that there was not much variance that could be accounted for by predictor variables. This was especially true for internalizing symptoms, in which the nonsignificant findings for the variance of the slope virtually guaranteed that our model would not fit data that described only modest associations between initial levels of internalizing symptoms and changes in perceived maternal and paternal social support. This view is bolstered by results from supplemental analyses that revealed significant associations between the intercept of internalizing symptoms and the slope of perceived social support at high initial levels of internalizing but not at average or low levels of internalizing. Future scholars with greater statistical power will be better equipped to determine whether child internalizing is a unique predictor of diminished parental support or whether this association is largely a function of the variance depression shares with conduct problems among subgroups of troubled youth.

This study is not the final word on the topic. With only three waves of data, we could not evaluate nonlinear change, an important consideration given that declines in perceived support are especially pronounced across the transition into adolescence (Shanahan, McHale, Crouter, & Osgood, 2007). Our study relied heavily on adolescent self-reports. We replicated many of the self-report findings with Grade 6 maternal reports, alleviating some concerns about shared reporter variance, but the analyses could not ascertain correlated changes between slopes of maternal report variables and slopes of child report variables. Our analyses were limited in terms of their ability to identify bidirectional effects. Multipanel (Cole & Maxwell, 2003) and latent difference score models have the potential to model dynamic associations between variables that are changing over time. However, even these tools cannot overcome limitations in the data because the common practice of assessing families at annual or semiannual intervals is ill-suited for capturing mechanisms of influence that are expressed in daily interchanges. The absence of reversal effects does not mean that parent support has no impact on adolescent behavior problems. Once psychopathology is established, substantial changes in family risk exposure are required to alleviate a disorder (Fergusson, Horwood, & Lynskey, 1992); our study could not address this possibility nor could it determine whether externalizing symptoms have origins in poor parenting during earlier developmental periods.

In closing, we note that the goal of quantifying parent– adolescent influences remains elusive. Short-term influence processes have been identified in families with children (Bell & Chapman, 1986), but long-term influence mechanisms have proven difficult to document across the adolescent years, in part because of the multiple transformations that take place during this age period. Child-driven effects have recently been specified in families with adolescent children in domains such as monitoring (Kerr, Stattin, & Burk, in press) and attachment security (Allen, McElhaney, Kuperminc, & Jodl, 2004). To this list we would add relationship quality as indexed by perceived parental support. These findings have important implications for families and therapists because they reinforce the emerging consensus that rapidly deteriorating parent–child relationships are not an inevitable feature of early adolescence but rather a developmental challenge confronted primarily by poorly adjusted youth and their families.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided to Brett Laursen by the U.S. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD33006).

References

- Achenbach TM. Integrative Guide for the 1991 CBCL/4–18, YSR, & T R F Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Adams RE, Laursen B. The correlates of conflict: Disagreement is not necessarily detrimental. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:445–458. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.3.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, McElhaney KB, Kuperminc GP, Jodl KM. Stability and change in attachment security across adolescence. Child Development. 2004;75:1792–1805. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00817.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle J. Amos 7.0 [Computer software] Chicago: Smallwaters; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, Stoltz HE, Olsen JA. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 4. Vol. 70. 2005. Parent support, psychological control, and behavioral control: Assessing relevance across time, culture, and method. (282). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RQ, Chapman M. Child effects in studies using experimental or brief longitudinal approaches to socialization. Developmental Psychology. 1986;22:595–603. [Google Scholar]

- Brendgen M, Wanner B, Morin AJS, Vitaro F. Relations with parents and with peers, temperament, and trajectories of depressed mood during early adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:579–594. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-6739-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA. Historical perspectives on contemporary research in social development. In: Smith P, Hart C, editors. Blackwell handbook of social development. Malden, MA: Blackwell; 2002. pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Maccoby EE, Steinberg L, Hetherington EM, Bornstein MH. Contemporary research on parenting: The case for nature and nurture. American Psychologist. 2000;55:218–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Steinberg L. Adolescent development in interpersonal context. In: Damon W, Lerner R, Eisenberg N, editors. The handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional and personality development. 6th. New York: Wiley; 2006. pp. 1003–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Deković M, Buist KL, Reitz E. Stability and changes in problem behavior during adolescence: Latent growth analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2004;33:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Nelson SE, Bullock BM. Premature adolescent autonomy: Parent disengagement and deviant peer process in the amplification of problem behavior. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27:515–530. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT. Family change, parental discord, and early offending. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1992;33:1059–1075. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1992.tb00925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W. The measurement of friendship perceptions: Conceptual and methodological issues. In: Bukowski WM, Newcomb AF, Hartup WW, editors. The company they keep: Friendship in childhood and adolescence. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 41–65. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Children's perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21:1016–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks of personal relationships. Child Development. 1992;63:103–1152. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb03599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galambos NL, Barker ET, Krahn HJ. Depression, self-esteem, and anger in emerging adulthood: Seven-year trajectories. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:350–365. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four Factor Index of Social Status. Yale University; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Huh D, Tristan J, Wade E, Stice E. Does problem behavior elicit poor parenting? A prospective study of adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2006;21:185–204. doi: 10.1177/0743558405285462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, Stattin H, Burk WJ. A reinterpretation of parental monitoring in longitudinal perspective. Journal of Research on Adolescence in press. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, Stattin H, Pakalniskiene V. Parents react to adolescent problem behaviors by worrying more and monitoring less. In: Kerr M, Stattin H, Engels RCME, editors. What can parents do? New insights into the role of parents in adolescent problem behavior. New York: Wiley; 2008. pp. 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Kuczynski L. Beyond bidirectionality: Bilateral conceptual frameworks for understanding dynamics in parent-child relations. In: Kyczynski L, editor. Handbook of dynamics in parent-child relations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW, Raffaelli M, Richards MH, Ham M, Jewell L. Ecology of depression in late childhood and early adolescence: A profile of daily states and activities. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1990;99:92–102. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.99.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW, Richards MH, Moneta G, Holmbeck G, Duckett E. Changes in adolescents' daily interactions with their families from ages 10 to 18: Disengagement and transformation. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:744–754. [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, Collins WA. Parent–child relationships during adolescence. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. 3rd. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, Furman W, Mooney KS. Predicting interpersonal competence and self-worth from adolescent relationships and relationship networks: Variable-centered and person-centered perspectives. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2006;52:572–600. [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, Hafen CA. Conflict is bad (except when its not) Social Development. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00546.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review. 1993;100:674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit GS, Bates JE, Dodge KA, Meece DW. The impact of after-school peer contact on early adolescent externalizing problems is moderated by parental monitoring, perceived neighborhood safety, and prior adjustment. Child Development. 1999;70:768–778. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers KN, Buchanan CM, Winchell ME. Psychological control during early adolescence: Links to adjustment in differing parent/adolescent dyads. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2003;23:349–383. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Beyond longitudinal data: Causes, consequences, changes, and continuity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:928–940. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.5.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Pickles A, Murray R, Eaves L. Testing hypotheses on specific environmental causes on behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:291–324. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.3.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan L, McHale SM, Crouter AC, Osgood DW. Warmth with mothers and fathers from middle childhood to late adolescence: Within- and between-families comparisons. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:551–563. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.3.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk JS, Steinberg L, Morris AS. Adolescents' emotion regulation in daily life: Links to depressive symptoms and problem behavior. Child Development. 2003;74:1869–1880. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Chao W, Conger RD, Elder GH. Quality of parenting as mediator of the effect of childhood defiance on adolescent friendship choices and delinquency: A growth curve analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG. Adolescents' and parents' conceptions of parental authority. Child Development. 1988;59:321–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1988.tb01469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Barrera M., Jr A longitudinal examination of reciprocal relations between perceived parenting and adolescents' substance use and externalizing behaviors. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:322–334. [Google Scholar]

- Susman EJ, Rogol A. Puberty and psychological development. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2004. pp. 15–44. [Google Scholar]

- Videon TM. Parent-child relations and children's psychological well-being. Do dads matter? Journal of Family Issues. 2005;1:55–78. [Google Scholar]

- Windle M. A longitudinal study of stress buffering for adolescent problem behaviors. Developmental Psychology. 1992;28:522–530. [Google Scholar]