Abstract

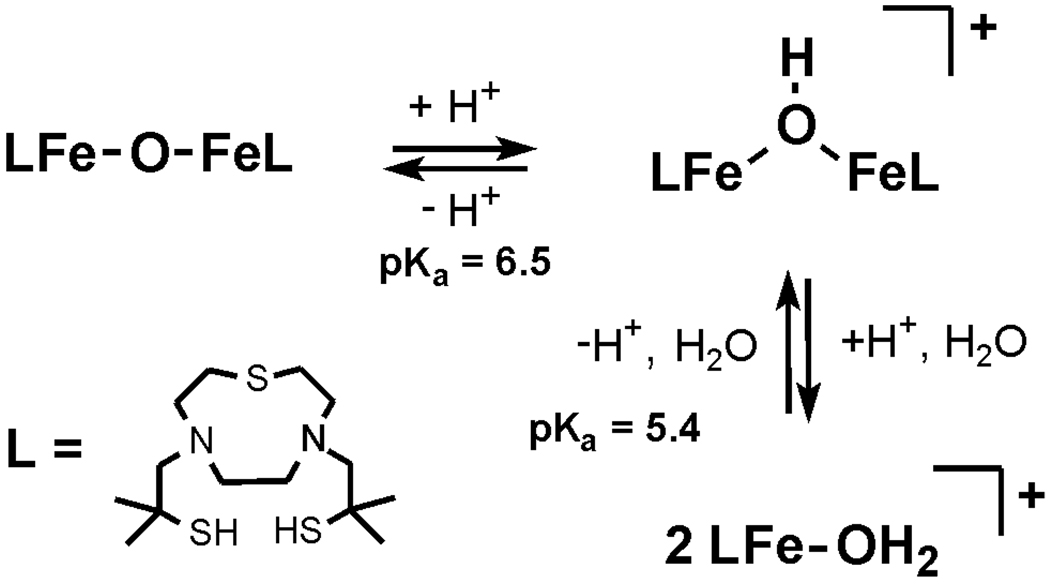

The five-coordinate iron-dithiolate complex (N,N′-4,7-bis-(2′-methyl-2′-mercatopropyl)-1-thia-4,7-diazacyclononane)iron(III), [LFe]+, has been isolated as the triflate salt from reaction of the previously reported LFeCl with thallium triflate. Spectroscopic characterization confirms an S = 1/2 ground state in non-coordinating solvents with room temperature µeff = 1.78 µB and EPR derived g-values of g1 = 2.06, g2 = 2.03 and g3 = 2.02. [LFe]+ binds a variety of coordinating solvents resulting in six-coordinate complexes [LFe-solvent]+. In acetonitrile the low-spin [LFe-NCMe]+ (g1 = 2.27, g2 = 2.18 and g3 = 1.98) is in equilibrium with [LFe]+ with a binding constant of Keq = 4.03 at room temperature. Binding of H2O, DMF, methanol, DMSO and pyridine to [LFe]+ yields high-spin six-coordinate complexes with EPR spectra that display significant strain in the rhombic zero-field splitting term E/D. Addition of one equivalent of triflic acid to the previously reported diiron species (LFe)2O results in the formation of [(LFe)2OH]OTf, which has been characterized by x-ray crystallography. The aqueous chemistry of [LFe]+ reveals three distinct species as a function of pH: [LFe-OH2]+, [(LFe)2OH]OTf, and (LFe)2O. The pKa values for [LFe-OH2]+ and [(LFe)2OH]OTf are 5.4 ± .1 and 6.52 ± .05 respectively.

Keywords: Iron-Thiolate, Nitrile Hydratase, EPR, Inorganic Modeling

Introduction

Small molecule model complexes of the non-heme iron enzyme nitrile hydratase (NHase) have been instrumental in elucidating the geometric and electronic structure of the enzyme active site.1–11 NHase, which catalyses the hydrolysis of nitriles to amides, possesses either a low-spin Fe(III) or non-corronid Co(III) in an unusual nitrogen/sulfur-rich environment with a primary coordination sphere consisting of two deprotonated amides from the peptide backbone, three cysteine derived sulfur donors (now known to exist in three different oxidation states), and a variable coordination site for interacting with substrates/products, Figure 1.12–18 Based on spectroscopic and computational results, several catalytic mechanisms have been proposed.4,8,19–21 Despite intensive efforts, it is still uncertain whether water, nitrile, or both substrates coordinate at the active site during catalysis.

Figure 1.

Representation of the active site of nitrile hydratase.

The substrate binding affinities of active site models have not provided consistent results.22,23 A high-spin (S = 5/2), five-coordinate iron complex with deprotonated amides and thiolate donors coordinates water, but shows no affinity for nitriles.22 A closely related low-spin (S = 1/2), five-coordinate iron complex featuring imine nitrogen donors and thiolates exclusively binds nitriles at low temperature, but undergoes ligand degradation upon exposure to water.23 To our knowledge, a single model complex that coordinates both nitrile and water has not yet been reported. In this manuscript we report the five-coordinate iron dithiolate, N,N′-Bis-(2′-methyl-2′-mercaptopropyl)-1-thia-4,7-diazacyclononane)iron(III) triflate ([LFe]OTf). [LFe]OTf binds water, nitriles and amides allowing for the first time a direct comparison of substrate (and product) binding affinities in a single model complex. Additionally, the pKa of the water and hydroxide bound derivatives of [LFe]OTf have been evaluated and offer insight regarding the need for low-spin iron at the enzyme active site.

Experimental Section

Materials and Methods

All reagents were obtained from commercially available sources and used as received unless otherwise noted. All solvents were dried and freshly distilled using standard techniques under a nitrogen atmosphere and degassed using freeze-pump-thaw techniques.24,25 All reactions were conducted using standard Schlenk techniques under an argon atmosphere or in an argon-filled glovebox unless otherwise noted.26 The complexes [(bmmp-TASN)FeCl], LFeCl, and [(bmmp-TASN)Fe]2O, (LFe)2O, were prepared as previously reported.2 Thallium triflate was prepared from thallium carbonate and triflic acid according to published protocols.27

N,N′-Bis-(2′-methyl-2′-mercaptopropyl)-1-thia-4,7-diazacyclononane iron(III) triflate ([LFe]OTf·0.5CH2Cl2)

To a suspension of 100 mg (0.24 mmol) LFeCl in 100 mL dry acetonitrile was added dropwise via cannula a solution of 86 mg (0.24 mmol) thallium triflate in 15 mL acetonitrile. After stirring for 15 hours, the solvent was removed under vacuum and the product extracted into 60 mL dichloromethane followed by filtration through a fritted tube. Removal of solvent from the filtrate yielded [LFe]OTf·0.5CH2Cl2 as a dark blue solid. Yield: 81 mg (0.15 mmol, 63 %). Electronic absorption (dichloromethane (22 °C)): λmax(ɛ): 274(7601), 317(6740), 427(2570), 504(1400), 623(1600). IR (KBr pellet), cm−1: 3436 (br), 2949 (m), 2912 (m), 2880 (m), 2843 (m), 1450 (m), 1262 (s), 1135 (m), 1102 (m), 1074 (m), 1029 (s), 804 (m), 636 (m). MS-ESI, m/z calcd. For C14H28N2S3Fe, [M+] 376.08; Found, 376.05. Anal. Calcd. for C15.5H31N2S4O3F3FeCl([LFe]OTf·0.5CH2Cl2): C, 31.48; H, 4.95; N, 4.59. Found: C, 31.17; H, 4.92; N, 4.88.

[(LFe)2OH]Tf

A solution of (LFe)2O (50 mg, 65 µmol) in 100 mL acetonitrile was cooled to −15 °C in a dry ice/ethylene glycol bath. A solution of 5.7 µL (9.7 mg, 65 µmol) 98% triflic acid in 10 mL acetonitrile was added dropwise via cannula over a 30 min. period. The solution was stirred for 2 hours as it gradually warmed to room temperature. The solution was filtered through a fritted tube and concentrated to 15 mL. Diethyl ether addition led to precipitation of [(LFe)2OH]Tf as a purple solid. Yield: 45 mg (49 µmol, 75%). X-ray quality crystals were obtained by vapor diffusion of diethyl ether into a methanol solution of 2 at 4 °C under an argon atmosphere. Electronic absorption (acetonitrile): λmax(ɛ): 311(3600), 433(700), 602(1600). IR (KBr pellet), cm−1: 3490 (br), 2958 (m), 2913 (m), 2880 (m), 2847 (m), 1454 (m), 1254 (s), 1147 (m), 1131 (m), 1074 (m), 1029 (s), 976 (m), 641 (s), 518 (m). Anal. Calcd. for C29H58N4S8O7F6Fe2([(LFe)2OH]OTf·HOTf): C, 36.24; H, 5.88; N, 5.64. Found: C, 36.92; H, 5.77; N, 5.57

Physical Methods

Elemental analyses were obtained from Midwest Microlab (Indianapolis, IN). Infrared spectra were recorded on a Thermo Nicolet Avatar 360 spectrometer at 4 cm−1 resolution. 1H NMR spectra were obtained on a Varian Inova500 500 MHz spectrometer. Mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) was performed by the Laboratory for Biological Mass Spectrometry at Texas A&M University. The room temperature magnetic moment of [LFe]OTf was determined by the Evan’s method in dichloromethane with use of residual CH2Cl2 peak and its shifted counterpart in calculation of µeff.28 Cyclic voltammetry was performed using a PAR 273 potentiostat with a three electrode cell (glassy carbon working electrode, platinum wire counter electrode, and a Ag/AgCl pseudo reference electrode) at room temperature in an argon filled glove box. All potentials were scaled to a ferrocene/ferrocenium standard using an internal reference. Catalytic trials (see Supporting Information) were monitored by gas chromatography using an HP 5890 series II chromatograph fitted with a flame ionization detector using compressed air as a carrier gas with an RTX-1 column (60 m length, i.d. 32, serial number 469083) from Restek Corporation.

Electronic absorption spectra were recorded with an Agilent 8453 diode array spectrometer with air free 1 cm path length quartz cell or in a custom made dewar with a 1 cm path length quartz sample compartment. The equilibrium constant for acetonitrile binding was determined as described in the Supporting Information based on minimization of the R2 value of the resulting van’t Hoff plot using previously reported methods:23,29 The pKa values for [LFe-OH2]+ and [(LFe)2OH]OTf were determined spectrophotometrically in a 70:30 water/acetone mixture due to poor solubility of (LFe)2O in aqueous solution30 using a Corning pH 440 meter with full details in the Supporting Information.

X-band EPR spectra were obtained either on a Bruker EMX EPR spectrometer (77 K, 6.3 mW, modulation amplitude 5 G) or on a Bruker EleXsys E600 spectrometer (20 K, 2 mW, modulation amplitude 10 G) equipped with an ER4116DM TE012/TE102 dual-mode cavity and an Oxford Instruments ESR900 helium flow cavity. The S = 1/2 spectra were modeled using SIMPOW.31 Computer simulations of S = 5/2 spectra were carried out using matrix diagonalization with XSophe v.1.1.3,32 assuming a spin Hamiltonian H = βg.B.S + S.D.S and including distributions (“strains”) in the zero-field splitting parameters, σD and σE/D.

Crystallographic Studies

A dark purple trapezoidal prism 0.29 × 0.22 × 0.05 mm3 crystal of [(LFe)2OH]OTf was selected for X-ray data collection on a Bruker SMART APEX CCD diffractometer. Frame data were collected (SMART33 v5.632) and processed (SAINT34 v6.45a) to determine final unit cell parameters: a = 15.472(6) Å, b = 10.629(4) Å, c = 25.894(13) Å, β= 95.172(5)°, V = 4241(3) Å3, Z = 4 and ρcalcd = 1.477 Mgm−3. The raw hkl data were corrected for absorption (SADABS35 v2.10; transmission min./max. = 0.744/0.948; µ= 1.082 mm−1) and the structure was solved by Patterson methods (SHELXTL36–38 (v 6.14) suite of programs) in the space group Ia. For all 9283 unique reflections (R(int) = 0.0273) the final anisotropic full matrix least-squares refinement on F2 for 468 variables converged at R1 = 0.0420 and wR2 = 0.0994 with a GOF of 1.08. Crystallographic parameters for [(LFe)2OH]OTf are displayed in Table 1 with additional experimental details provided in the Supporting Information.

Table 1.

Crystal data and structure refinement for [(LFe)2OH]OTf.

| Identification code | [(LFe)2OH]OTf |

| Empirical formula | C29H57F3Fe2N4O4 S7 · 0.75(CH3OH) |

| Formula weight | 942.94 |

| Temperature | 100(2) K |

| Wavelength | 0.71073 Å |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic |

| Space group | Ia |

| Unit cell dimensions | a = 15.472(6) Å |

| b = 10.629(4) Å | |

| c = 25.894(13) Å | |

| β= 95.172(5)°. | |

| Volume | 4241(3) Å3 |

| Z | 4 |

| Density (calculated) | 1.477 Mg/m3 |

| Absorption coefficient | 1.082 mm−1 |

| F(000) | 1982 |

| Crystal size | 0.29 × 0.22 × 0.05 mm3 |

| Theta range for data collection | 2.64 to 28.14° |

| Crystal color, habit | dark purple trapezoidal prism |

| Index ranges | −20<=h<=20 |

| −14<=k<=13 | |

| −33<=l<=33 | |

| Reflections collected | 18021 |

| Independent reflections | 9283 [R(int) = 0.0273] |

| Completeness to theta = 28.14° | 95.7 % |

| Absorption correction | SADABS |

| Max. and min. transmission | 0.948 and 0.744 |

| Refinement method | Full-matrix least-squares on F2 |

| Data / restraints / parameters | 9283 / 4 / 468 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.08 |

| Final R indices [I>2sigma(I)] | R1 = 0.0388, wR2 = 0.0965 |

| R indices (all data) | R1 = 0.0420, wR2 = 0.0994 |

| Absolute structure parameter | 0.030(12) |

| Largest diff. peak and hole | 1.092 and −0.326 e.Å−3 |

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and Characterization

Previously we reported LFeCl (L = bmmp-TASN) as a model complex of nitrile hydratase.2 The coordinated chloride was not displaced by water or nitrile, although under basic conditions the µ-oxo complex (LFe)2O was obtained. Herein we report metathesis of the chloride with thallium triflate to yield the five-coordinate complex [LFe]OTf, Scheme 1. The infrared spectrum of [LFe]OTf displays strong absorptions at 1262 and 1029 cm−1 attributed to the triflate counter ion, but is otherwise similar to that of LFeCl. The room temperature magnetic moment of [LFe]OTf in dichloromethane (1.78 µB) is consistent with the spin-only value for low-spin iron(III). Mass spectral analysis of [LFe]OTf from dichloromethane, acetonitrile or aqueous solutions displays a major peak at m/z = 376.08 as expected for [LFe]+ with no evidence of triflate or solvent coordination in the gas phase.

Scheme 1.

As a solid [LFe]OTf is vivid blue, however, in solution the color depends on equilibrium solvent binding. In water, three species ([LFe-OH2]+, [(LFe)2OH]+, and (LFe)2O) were observed as a function of pH. [(LFe)2OH]OTf is also obtained by stoichiometric addition of triflic acid to acetontrile solutions of (LFe)2O with a corresponding bathochromic shift in the low energy absorption band from 553 to 603 nm, Figure 2. The infrared spectrum of [(LFe)2OH]OTf is marked by bands at 1254 and 1029 cm−1 due to the triflate counter ion. Also of note is the absence of the Fe-O-Fe stretch at 800 cm−1 found in the IR spectrum of the precursor µ-oxo complex.2 The [(LFe)2OH]OTf complex is soluble in water, acetonitrile, alcohols, and sparingly soluble in dichloromethane, yielding violet colored solutions in each case.

Figure 2.

UV/visible spectrum of the synthesis of [(LFe)2OH]OTf (3 mM) in acetonitrile.

Structural Characterization of [(LFe)2OH]OTf

The complex [(LFe)2OH]OTf crystallizes in the monoclinic space group Ia with one metal containing cation, [(LFe)2OH]+, one triflate anion, and a partial occupancy methanol solvent molecule. The position of the hydrogen atom of the bridging hydroxide was determined from an electron density map and refined isotropically. An ORTEP39 representation of [(LFe)2OH]+ is presented in Figure 3 with selected bond distances and angles given in Table 2. As with all other complexes of L, the TASN ligand backbone constrains the two amines and thioether sulfur to a facial coordination mode.1,2,11 For each iron center, the three sulfur donors are meridional with each sulfur cis to the hydroxide bridge. An amine nitrogen occupies the position trans to the bridging hydroxide. The iron-ligand bond distances of [(LFe)2OH]+ are within the ranges expected for high spin Fe(III).2,11,40

Figure 3.

ORTEP view of [(LFe)2OH]+ showing 30% probability displacement ellipsoids. Calculated H atoms, solvent and triflate counter ion have been omitted.

Table 2.

Selected Bond Distances (Ǻ) and Bond Angles (deg) for [(LFe)2OH]OTf

| Fe1-S1 | 2.3004(12) | Fe1-N1 | 2.263(3) |

| Fe1-S2 | 2.3262(13) | Fe1-N2 | 2.242(3) |

| Fe1-S3 | 2.5385(14) | Fe1-O1 | 2.002(3) |

| Fe2-S4 | 2.3250(12) | Fe2-N3 | 2.244(3) |

| Fe2-S5 | 2.2961(12) | Fe2-N4 | 2.258(3) |

| Fe2-S6 | 2.5565(13) | Fe2-O1 | 1.998(3) |

| O1-H1o | 0.841(19) | ||

| N1-Fe1-N2 | 79.10(11) | N1-Fe1-S1 | 83.56(8) |

| N2-Fe1-S2 | 84.11(8) | N1-Fe1-S2 | 96.11(8) |

| N2-Fe1-S3 | 80.71(8) | S1-Fe1-S2 | 102.22(4) |

| O1-Fe1-S2 | 93.91(8) | Fe1-O1-Fe2 | 166.71(14) |

| N3-Fe2-N4 | 78.86(11) | N3-Fe2-S4 | 84.26(9) |

| N3-Fe2-S6 | 81.10(8) | N4-Fe2-S5 | 83.95(8) |

| N4-Fe2-S6 | 80.96(8) | S4-Fe2-S5 | 100.95(4) |

| Fe1-O1-H10 | 96(3) | Fe2-O1-H10 | 98(3) |

Comparison of the structure of [(LFe)2OH]OTf with previously reported crystallographic data for the related µ-oxo complex, (LFe)2O, reveals important distinctions between the two structures.2 The Fe-O-Fe angle for [(LFe)2OH]+ is 166.71(14)°, while the corresponding angle for (LFe)2O is 180.0°. This decrease in Fe-O-Fe bond angle results from protonation of the bridging oxo ligand.41–43 The steric bulk of the ligands force a severe distortion of the idealized trigonal arrangement about the bridging oxygen atom, with Fe-O-H angles compressed to an average of 97°.

Solution Studies

The complex [LFe]OTf is soluble in a wide variety of polar and non-polar solvents yielding vivid green (5-coordinate) or blue (six-coordinate) solutions. A low energy charge transfer band near 600 nm, assigned as a thiolate to iron charge transfer, is observed for all six-coordinate complexes assigned as either [LFe-solvent]+ or LFe-OTf, depending on reaction conditions.44,45 In contrast, the 5-coordinate complex, [LFe]+ displays a lower energy band at 623 nm and a distinct shoulder at 427 nm.

Vacant Binding Site: Five-coordinate, S = 1/2

Dichloromethane solutions of [LFe]OTf are green in color at all temperatures above −40 °C indicative of five-coordinate [LFe]+. The room temperature UV-visible spectrum displays diagnostic bands at 315, 427, and 623 nm. Upon cooling to temperatures below −40 °C the color changes from green to blue due to coordination of triflate. As shown in Figure S1, the low energy band shifts from 623 nm to 603 nm and the shoulder at 427 nm decreases in intensity.

The lack of triflate coordination at room temperature is also evident in the cyclic voltammogram. In dichloromethane [LFe]OTf displays a pseudo-reversible event at −500 mV (vs Fc/Fc+) assigned as FeIII/II and an irreversible oxidation at 510 mV assigned to the ligand, Figure S2. The metal-based reduction potential is shifted by +560 mV with respect to LFeCl consistent with the loss of a donor atom. The oxidation is similarly shifted.

The EPR spectrum of [LFe]OTf in dichloromethane (77 K) indicates incomplete triflate coordination even at low temperature. The spectrum reveals a sharp signal for a low-spin component and a broad complex high-spin signal, Figure S3, that gains intensity as the temperature is lowered, Figure S4. The sharper signal attributable to [LFe]+ was simulated (SIMPOW) with g-values of 2.06, 2.03, and 2.02, Figure 4.31 This narrow g-value spread is atypical of low-spin iron(III)46,47 and more akin to that of metal-coordinated thiyl radicals, which show significantly less delocalization onto aromatic ligands than their phenoxyl counterparts.48 Computational investigations by our group and others on low-spin iron(III)-thiolates show significant spin-density on sulfur (even in the absence of aromatic ligands) consistent with Fe(II)-thiyl radical character.5,11 The observed S = 1/2 ground state is consistent with increased Fe-S covalency as the thiolate compensates for the loss of the sixth donor and could result from coupling of either intermediate- or low-spin Fe(II) with the thiyl radical.5,11

Figure 4.

EPR spectrum (77 K) of [LFe]OTf in dichloromethane with simulation. Experimental Parameters: Microwave power = 6.3 mW, Modulation Amplitude = 5.35G. Simulation parameters: g1 = 2.06, g2 = 2.03, g3 = 2.02, W1 = 21.80, W2 = 39.87, W3 = 21.23.

Nitrile Binding: Six-coordinate, S = 1/2

The low affinity of [LFe]+ for triflate ensures an accessible coordination site for solvent (substrate) binding. At 40 °C in acetonitrile solutions of [LFe]+ are green with absorbance bands at 315, 427, and 603 nm similar to the spectrum observed in dichloromethane and consistent with a five-coordinate complex. However, upon cooling to room temperature and below the solution takes on a blue color as the peak at 427 nm loses intensity and the low energy band shifts towards 596 nm, Figure 5. The onset of these changes occurs at significantly higher temperature than in dichloromethane and arises due to nitrile coordination. The apparent equilibrium constants for nitrile binding of 4.7 at 298 K and 25 at −40 °C are similar to those reported by Kovacs in a related model complex.23

Figure 5.

Variable temperature (40 °C to −43 °C) UV/visible spectra of [LFe]OTf (3 mM) in acetonitrile. Arrows denote changes in the spectra as the temperature is lowered.

The coordination of acetonitrile at room temperature is confirmed by cyclic voltammetry. The CV of [LFe]OTf in acetonitrile, Figure S2, displays a reversible event at −622 mV (vs. Fc/Fc+) assigned to the FeIII/II couple of [LFe-NCMe]+ and a chemically irreversible oxidation at 166 mV. The reduction potential is shifted by −120 mV as compared to that of [LFe]+ consistent with the addition of a weakly coordinating ligand.

The EPR spectrum of [LFe]OTf (acetonitrile glass 77 K) also confirms equilibrium binding of acetonitrile, Figure 6A. In addition to the sharp axial signal of [LFe]+ (g1 = 2.04, g2 = 2.02, g3 = 2.01; 7% relative intensity), the spectrum also displays a rhombic signal (g1 = 2.27, g2 = 2.18, g3 = 1.98; 93% relative intensity) attributed to [LFe-NCMe]+. The large anisotropy in the g-values is typical of low-spin, six-coordinate Fe(III) complexes.46,47

Figure 6.

EPR spectra of [LFe]OTf in acetonitrile (A) with simulation (B) and [LFe]OTf in benzonitrile (C) with simulaton (D). Experimental parameters: (A) microwave Power = 1.5 mW, modulation amplitude = 8.09 G; (C) microwave power = 1.99 mW, modulation amplitude = 6.00 G. Simulation parameters: (B) for [LFe]+ g1 = 2.04, g2 = 2.01, g3 = 2.02, W1 = 19.40, W2 = 28.15, W3 = 25.80 and [LFe-NCMe]+ g1 = 2.27, g2 = 2.18, g3 = 1.98, W1 = 17.95, W2 = 91.21, W3 = 33.17; (D) for [LFe]+: g1 = 2.06, g2 = 2.03, g3 = 2.03, W1 = 21.73, W2 = 40.05, W3 = 21.08 and [LFe-NCPh]+: g1 = 2.28, g2 = 2.18, g3 = 2.00, W1 = 64.78, W2 = 26.50, W3 = 46.33.

Similar results are obtained in benzonitrile, Figure 6B. A rhombic signal (g1 = 2.28, g2 = 2.18, g3 = 2.00, relative intensity 85%) attributed to [LFe-NCPh]+ is observed in addition to the axial signal of [LFe]+. The similarity in g-values for the two nitrile bound derivatives [LFe-NCMe]+ and [LFe-NCPh]+ implies that the identity of the nitrile donor does not significantly influence the electronic environment. This is consistent with recent computational studies that suggest the nitrile is not significantly polarized upon coordination to iron in NHase in contrast to expectations for a nitrile bound mechanism.49

Water and other donor solvents: Six-coordinate, S = 5/2

The donor ability of nitriles to [LFe]+ is limited and low temperatures are required to facilitate coordination. Other solvents including water and DMF more strongly coordinate [LFe]+ leading to high-spin derivatives. Solutions of [LFe]+ in H2O (pH < 6.1), DMF, DMSO, pyridine, or methanol are dark blue at all temperatures with a charge transfer band near 600 nm and no shoulder at 427 nm. The low energy band blue-shifts with increased σ-donor ability of the sixth ligand, although in H-donor solvents the shift is tempered by interactions between the solvent and sulfur, Table S1.

The best evidence for solvent coordination is obtained from EPR spectroscopy. The complex EPR spectra of [LFe]OTf in DMSO, pyridine, methanol, DMF and water display multiple broad turning points between 500–4000 G, Figure 7. The observed spectra are similar to those reported in literature for other iron complexes with thiolate or chloride donors.22,50,51 Despite the complexity of the spectra, the vast majority of the signal intensity (> 99 % of the spins) can be simulated as a single monomeric highspin iron complex with trace quantities of a geff ~ 4.3 signal as described below.

Figure 7.

EPR spectra of [LFe]OTf in various solvents. All spectra recorded at 20 K except DMF (77 K).

The EPR signals shown in Figure 7 are similar to those reported for iron-catecholate complexes52 in that the strain in E (here characterized as a strain in E/D) extended the envelope of E/D such that one of the “preferred” values of E/D was exhibited by some of the molecules. These preferred values give rise to apparently anomalously intense features in the EPR spectrum due to partial or total lack of orientation selection in the powder spectrum.53 In the case of the catecholate species, the strains in E were sufficiently high that the spectra exhibited an intense component at geff ~ 4.3 due to a subpopulation with E/D ~ 1/3, although the mean value of E/D was as low as 0.120.

The strain-dependent appearance of the geff ~ 4.3 resonance can be appreciated by comparing the calculated spectra of Figure 8A and B, that have identical spin Hamiltonian parameters except for the strain in E/D. In the present case, the signals from [LFe]OTf exhibit low field lines that are split by only about 170 G (17 mT), compared to about 500 G (50 mT) for the catecholate complexes. Simulations (Figure 8B – E) indicate that the smaller splitting is due to a lower mean E/D of 0.045. One of the consequences of this lower value for E/D is a change in the relative intensities of the two low field lines; gx and gy for the mS = 3/2 Kramers’ doublet of S = 5/2 approach zero as E/D decreases and the spectrum spans an increasingly wide field envelope, leading to a diminution of the intensity of the higher-field line of the pair (the gz resonance of mS = 3/2, at 1200 G [120 mT], geff ~ 5.7). As strains in E/D are introduced (Figure 8F – M), this feature appears to grow in intensity again. However, unlike the lowest field resonance of mS = 1/2 at 1000 G (100 mT; geff ~ 6.6), the line at 1200 G does not become broadened at successively higher values of σE/D. In addition, it shifts slightly to a resonance position corresponding to geff = 6.0 and assumes a typical gx-gy derivative shape. Thus the resonance observed is actually due to strain-dependent access of the preferred E/D value of zero, giving rise to an intense resonance due to the gx and gy transitions in mS = 1/2. Only when very high E/D-strain is present is the geff ~ 4.3 line observed (Figure 8M). At such a high value of σE/D, only the preferred resonances (geff ~ 6, E/D ~ 0 and geff ~ 4.3, E/D ~ 1/3) are resolved. As expected from the above assignment, the relative intensities of the geff ~ 6 and geff ~ 4.3 resonances change upon raising E/D, with the higher value of E/D favoring geff ~ 4.3.

Figure 8.

Calculated High-Spin Spectra. High-spin spectra were calculated assuming S = 5/2, giso = 1.995, and (A) D = 0.45 cm−1, E/D = 0.165, σE/D = 0.08; (B) D = 0.45 cm−1, E/D = 0.165, σE/D = 0; (C) D = 0.45 cm−1, E/D = 0.125, σE/D = 0; (D) D = 0.45 cm−1, E/D = 0.085, σE/D = 0; (E) D = 0.45 cm−1, E/D = 0.045, σE/D = 0; (F) D = 0.45 cm−1, E/D = 0.045, σE/D = 0.010; (G) D = 0.45 cm−1, E/D = 0.045, σE/D = 0.015; (H) D = 0.45 cm−1, E/D = 0.045, σE/D = 0.020; (I) D = 0.45 cm− 1, E/D = 0.045, σE/D = 0.025; (J) D = 0.45 cm−1, E/D = 0.045, σE/D = 0.035; (K) D = 0.45 cm−1, E/D = 0.045, σE/D = 0.045; (L) D = 0.45 cm−1, E/D = 0.045, σE/D = 0.100; (M) D = 0.45 cm−1, E/D = 0.045, σE/D = 0.320; (N) D = 0.45 cm−1, E/D = 0.130, σE/D = 0.320.

From the simulations displayed in Figure 8, the high spin spectra of [LFe]OTf in H2O, pyridine, DMSO, methanol and DMF can be explained as containing contributions from a slightly rhombic (E/D = 0.045) S = 5/2 Fe(III) species that exhibits strain in E/D, and an additional component that is responsible for the geff = 4.3 line. The strains in the slightly rhombic species result in a broadened resonance at geff ~ 6.6, due to the E/D envelope associated with the gx transition in mS = 1/2, and a resonance at geff = 6.0 due to the gx and gy transitions in a subpopulation with the preferred value of E/D ~ 0. As is also evident from the simulations, when E/D is sufficiently small to account for the resonance positions observed, and when σE/D is sufficiently small that the geff ~ 6.6 resonance is resolved, there is no significant contribution to the spectrum from the mS = 3/2 doublet, in contrast to the spectra of iron-catecholate complexes. The geff = 4.3 line must, therefore, arise from a separate Fe(III) species most likely due to complex degradation. The spectrum of [LFe]OTf in DMSO was simulated as such, Figure S5, and integration of the simulations indicated that the slightly rhombic species that exhibit the mS = 1/2 resonances accounted for 85 % of the spins (note that much of the spectral intensity is at high field and is virtually undetectable in the derivative spectrum), and the geff = 4.3 line accounts for about 15 % of the spins.

The EPR simulations for [LFe]OTf in DMSO reveal the majority of the spin density is attributable to the six-coordinate [LFe-DMSO]OTf. That the high-spin EPR signal indeed arises from solvent-bound species is evidenced by the spectra of [LFe-pyridine]OTf, in which pervasive super-hyperfine coupling to nitrogen is present in the majority of the signal. Similar spectral characteristics displayed in σ-donor solvents are consistent with the formation of six-coordinate high-spin Fe(III) complexes. The spectrum of [LFe-HOMe]OTf also displays the sharp signal of [LFe]+ (g = 2.04, 2.02, and 2.01) consistent with weak coordination. The predominance of the high spin complex despite the binding of strong σ-donors (e.g. DMSO, pyridine) suggests that π-affects are instrumental in determining the spin state of iron in these complexes.

Solvent competition studies

The unique ability of [LFe]+ to bind both substrates (water and nitriles) as well as product (amide) provides the opportunity to directly probe binding preferences for iron in a nitrile hydratase model complex. The iron displays a preference for water over nitrile. Addition of nitriles to [LFe-OH2]+ at a pH of 3.0 shows no spectroscopically detectable changes in the UV-visible or EPR spectra. Addition of nitriles to [(LFe)2OH]+ at a pH of 6.1 (vida infra) also reveals no detectable changes. In contrast, addition of pH = 6.1 buffered H2O (100 equivalents H2O per Fe) to acetonitrile solutions of [LFe]+ in which the nitrile concentration exceeds the water concentration by three orders of magnitude results in significant spectroscopic changes. The charge transfer band in the UV-visible spectrum broadens and red shifts to 602 nm and the EPR spectrum is silent consistent with formation of the dinuclear complex [(LFe)2OH]+ and no detectable quantities of [LFe-NCMe]+.

Although the above experiments clearly demonstrate the affinity of iron for water over nitriles, this preference extends even when sub-stoichiometric quantities of water are added to acetonitrile solutions of [LFe]OTf. Careful addition of one equivalent of triflic acid to the µ-oxo complex (LFe)2O in acetonitrile leads to a red shifting of the charge transfer band from 560 nm to 603 nm consistent with protonation of the oxo bridge yielding [(LFe)2OH]+, which is EPR silent (vida infra). Careful addition of a second equivalent of triflic acid protonates the bridging hydroxide generating one equivalent of water for every two equivalents of [LFe]OTf. Water coordination is confirmed spectroscopically by a shift in the low energy band from 603 to 628 nm, Figure S7. The EPR spectrum of the reaction mixture, Figure S8, reveals the expected iron-containing products [LFe-OH2]+ and [LFe-NCMe]+ (in equilibrium with [LFe]+).

The relative binding affinity of [LFe]OTf for amides as compared to nitrile and water was determined through additions of small amounts of DMF to solutions of [LFe]OTf in acetonitrile and pH = 5 buffered water, respectively. The UV-visible and EPR spectra of [LFe-OH2]+ in buffered aqueous solution remain unchanged upon addition of 10 equivalents DMF, denoting the preference for water over DMF. Addition of 10 equivalents DMF to acetonitrile solutions of [LFe]OTf is best monitored by EPR, since the UV-visible spectra of [LFe]OTf in the two solvents is similar. The EPR shows no trace of the low spin signals of [LFe-NCMe]+ or [LFe]+. In fact, the spectrum is dominated by the high-spin signal previously observed for [LFe-DMF]+. Overall, the competition studies reveal that [LFe]OTf prefers catalytically relevant ligands in the order H2O > amide > nitrile.

Aqueous Chemistry

Given the strong preference for water coordination to [LFe]OTf, its aqueous chemistry was further explored. As outlined in Scheme 2, three discrete derivatives of [LFe]OTf are accessible as a function of pH. At pH < 5.0 (dilute triflic acid) [LFe-OH2]+ is present as a dark blue solution with bands at 315 and 613 nm. In addition to deprotonation events described below, the coordinate thiolates of [LFe-OH2]+ may be protonated but only at pH values lower than 3.00 at which point complex degradation occurs. Similar remarkable acid stability of an iron-thiolate has been previously reported for a NHase model complex with deprotonated amide donors in place of the amines found in [LFe]OTf.10

Scheme 2.

Titration of aqueous solutions of [LFe-OH2]+ with NaOH first yields the µ-OH complex [(LFe)2OH]+. Monitoring of the reaction by UV-visible spectroscopy reveals a blue shift of the low energy band from 613 to 603 nm. At pH = 6.10, the charge transfer band at 603 nm reaches its maximum intensity and the solution develops an intense violet color. The violet solution is EPR silent suggesting a strong anti-ferromagnetic coupling of the two high-spin iron(III) centers. No intermediate is detectable by UV-visible spectroscopy suggesting the mononuclear LFe-OH rapidly proceeds to [(LFe)2OH]+ once generated. Continued titration of [(LFe)2OH]+ leads to a further blue shifting of the charge transfer band from 603 nm to 560 nm. The resulting burgundy colored solution is characteristic of the previously reported µ-oxo complex (LFe)2O. Due to the poor water solubility of (LFe)2O reliable pKa values could not be obtained. The titration was repeated in buffered 70:30 water/acetone mixtures yielding similar results, with the exception that (LFe)2O did not precipitate, Figure S6. From this data, the pKa of the water bound complex [LFe-OH2]+ is estimated as 5.4 ± 0.1, while that of [(LFe)2OH]+ is 6.52 ± .05.

Trials for catalytic activity

The catalytic competency of [LFe]OTf towards the hydrolysis of nitriles was evaluated by addition of benzonitrile to room-temperature buffered aqueous solutions of [LFe]OTf at pH 6.10 and 3.03. At pH 6.10, [(LFe)2OH]+ is the dominant iron species in solution, while [LFe-OH2]+ is predominate at pH 3.03. The reaction mixtures were analyzed by gas chromatography for the presence of hydrolysis products benzamide and benzoic acid in organic extracts of the reaction mixture. No trace of hydrolysis products were detected under either set of conditions.

Conclusions and Relevance to Nitrile Hydratase

The complex [LFe]OTf has for the first time allowed direct competition studies to evaluate the relative binding affinities of water, nitriles, and amides in a nitrile hydratase model. The observed ligand binding affinity of H2O > amide > nitrile reveals that water coordination is favored over nitrile binding. Additionally, the preference for amides over nitriles further decreases the probability of a nitrile bound mechanism, since product release would also be problematic.

The only previously reported iron model complex of nitrile hydratase that coordinates nitriles, [FeIII(S2Me2N3(Et,Pr))]+, cannot bind water due to ligand degradation in aqueous environments.23 Our model binds nitriles with a similar affinity as [FeIII(S2Me2N3(Et,Pr))]+, but it also binds water much more tightly. The coordination of water to [LFe]OTf is similar to that observed in the Mascharak model complex, [FeIII(PyPS)]−. However, in that case no nitrile binding was observed precluding a direct and definitive comparison with the [FeIII(S2Me2N3(Et,Pr))]+ model.22 The Mascharak aquo complex is low-spin in contrast to our high-spin model suggesting that either spin state shows a strong affinity for water over nitriles. Our results bridge the prior studies and lend credence to a water-bound mechanism.

While both [LFe]OTf and [FeIII(PyPS)]− bind H2O, the former is high-spin and the latter is low-spin.22 The pKa values reveal that the high-spin [LFe-OH2]+ (5.4 ± .1) is almost ten times as acidic the low-spin [FeIII(PyPS)(H2O)]− (6.3).22 Recently we reported that oxygen sensitivity of iron-thiolates is likely spin-state dependent and question if similar effects may also influence the pKa of coordinated water.11 From a simple electrostatic approach, the relatively smaller ionic radius of low-spin iron(III) should lower the pKa of bound-water more efficiently than high-spin iron(III). However, this approach ignores π-interactions between the metal center and water/hydroxide that have been shown to be important for low-spin, but not high-spin, Fe(III).43 The π-interactions between the lone pair on HO− and a filled/nearly filled “t2g” orbital on low-spin Fe(III) would destabilize hydroxide coordination and raise the pKa. Additionally, the π-interactions may promote the nucleophilic character of the coordinated HO− similar to effects in metal-thiolates that yield nucleophilic sulfur.54,55 Overall, the low-spin state may modulate the pKa while maintaining significant nucleophilic character. In contrast, the more acidic highspin derivatives may lack a sufficiently nucleophilic hydroxide and even undergo further deprotonation to µ-oxo species in model complexes. Further studies to confirm these hypotheses are underway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation CAREER Award (CHE-0238137) with continued support by (CHE-0749965). MSM thanks the Kentucky Research Challenge Trust Fund for upgrade of our X-ray facilities. EPR studies were supported in part by an NIH P41 grant (EB001980) to the National Biomedical EPR Center.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Expanded experimental protocols, EPR and UV/visible spectra, and cyclic voltammetry of [LFe]OTf, and EPR simulations of [LFe-DMSO]OTf in PDF format and crystallographic data in CIF format (CCDC 708538). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Grapperhaus CA, Patra AK, Mashuta MS. Inorg. Chem. 2002;41:1039–1041. doi: 10.1021/ic015629x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grapperhaus CA, Li M, Patra AK, Poturovic S, Kozlowski PM, Zgierski MZ, Mashuta MS. Inorg. Chem. 2003;42:4382–4388. doi: 10.1021/ic026239t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mascharak PK. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2002;225:201–214. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kovacs JA. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:825–848. doi: 10.1021/cr020619e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lugo-Mas P, Dey A, Xu L, Davin SD, Benedict J, Kaminsky W, Hodgson KO, Hedman B, Solomon EI, Kovacs JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:11211–11221. doi: 10.1021/ja062706k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee CM, Hsieh CH, Dutta A, Lee GH, Liaw WF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:11492–11493. doi: 10.1021/ja035292t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kung I, Schweitzer D, Shearer J, Taylor WD, Jackson HL, Lovell S, Kovacs JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:8299–8300. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrop TC, Mascharak PK. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004;37:253–260. doi: 10.1021/ar0301532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galardon E, Giorgi M, Artaud I. Chem. Comm. 2004:286–287. doi: 10.1039/b312318a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Artaud I, Chatel S, Chauvin AS, Bonnet D, Kopf MA, Leduc P. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1999;192:577–586. [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Toole MG, Kreso M, Kozlowski PM, Mashuta MS, Grapperhaus CA. J. Bio. Inorg. Chem. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s00775-008-0405-4. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asano Y, Tani Y, Yamada H. Agr. Biol. Chem. Tokyo. 1980;44:2251–2252. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Endo I, Nakasako M, Nagashima S, Dohmae N, Tsujimura M, Takio K, Odaka M, Yohda M, Kamiya NJ. Inorg. Biochem. 1999;74:22–22. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Endo I, Odaka M, Yohda M. Trends Biotechnol. 1999;17:244–249. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(99)01303-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobayashi M, Shimizu S. Nat. Biotechnol. 1998;16:733–736. doi: 10.1038/nbt0898-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson MJ, Jin HY, Turner IM, Grove G, Scarrow RC, Brennan BA, Que LJ. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:7072–7073. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamada H, Kobayashi M. Biosci Biotech Bioch. 1996;60:1391–1400. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60.1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shigehiro S, Nakasako M, Dohmae N, Tsujimura M, Tokoi K, Odaka M, Yohda M, Kamiya N, Endo I. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:347–351. doi: 10.1038/nsb0598-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hopmann KH, Himo F. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2008:1406–1412. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hopmann KH, Guo JD, Himo F. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:4850–4856. doi: 10.1021/ic061894c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greene SN, Richards NG. J. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:17–36. doi: 10.1021/ic050965p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noveron JC, Olmstead MM, Mascharak PK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:3247–3259. doi: 10.1021/ja001253v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shearer J, Jackson HL, Schweitzer D, Rittenberg DK, Leavy TM, Kaminsky W, Scarrow RC, Kovacs JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:11417–11428. doi: 10.1021/ja012555f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armarego WLF, Perrin DD. Purification of Laboratory Chemicals. 4th ed. Oxford: Butterworth Heinimann; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gordon AJ, Ford RA. The Chemist's Companion. A Handbook of Practical Data, Techniques, and References. (1st ed) 1973 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shriver DF, Drezdon MA. The Manipulation of Air-Sensitive Compounds. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woodhouse ME, Lewis FD, Marks TJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:5586–5594. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Evans DF. Proc. Chem. Soc. 1959;115:2003–2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellison JJ, Nienstedt A, Shoner SC, Barnhart D, Cowen JA, Kovacs JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:5691–5700. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Albert A, Serjeant EP. Ionization Constants of Acids and Bases. Methuen, New York: Wiley; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nilges MJ. Ph.D. Thesis. Urbana: University of Illinois; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanson GR, Gates KE, Noble CJ, Mitchell A, Benson S, Griffin M, Burrage K. In EPR of Free Radicals in Solids. In: Shiotani M, Lund A, editors. Trends in Methods and Applications. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 33.SMART. Madison, WI: Bruker Advanced X-ray Solutions, Inc.; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 34.SAINT. Madison, WI: Bruker Advanced X-ray Solutions, Inc.; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 35.SADABS. Germany: Gottingen; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 36.SHELXTL 6.14. Program Library for Structure Solution and Molecular graphics, Bruker Advanced X-Ray Solutions. Masdison, WI: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheldrick GM. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Crystallogr. 2008;A64:112–122. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.SHELXL-97. Program for the Refinement of Crystal Structures. Gottingen, Germany: University of Gottingen; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farrugia LJ. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1997;30:565. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dey A, Jenney FE, Adams MWW, Johnson MK, Hodgson KO, Hedman B, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12418–12431. doi: 10.1021/ja064167p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mosseri S, Mialocq JC, Perly B, Hambright PJ. Phys. Chem. 1991;95:4659–4663. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Evans DR, Mathur RS, Heerwegh K, Reed CA, Xie Z. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1997;36:1335–1337. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Evans DR, Reed RA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:4660–4667. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kennepohl P, Neese F, Schweitzer D, Jackson HL, Kovacs JA, Solomon EI. Inorg. Chem. 2005;44:1826–1836. doi: 10.1021/ic0487068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Noveron JC, Herradora R, Olmstead MM, Mascharak PK. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1999;285:269–276. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Griffith JS. Proc. R. Soc. London, A. 1956;235:23–26. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taylor CP. S. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1977;491:137–149. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(77)90049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patra AK, Bill E, Bothe E, Chlopek K, Neese F, Weyhermuller T, Stobie K, Ward MD, McCleverty JA, Wieghardt K. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:7877–7890. doi: 10.1021/ic061171t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hopmann KH, Guo JD, Himo F. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:4850–4856. doi: 10.1021/ic061894c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rodriguez M, Morenstern-Badarau; Cesario M, Guilhem J, Keita B, Nadjo L. Inorg. Chem. 1996;35:7804–7810. doi: 10.1021/ic961369l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strautmann JBH, George SD, Bothe E, Bill E, Weyhermuller T, Stammler A, Bogge H, Glaser T. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:6804–6824. doi: 10.1021/ic800335t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weisser JT, Nilges MJ, Sever MJ, Wilker JJ. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:7736–7747. doi: 10.1021/ic060685p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Copik AJ, Waterson S, Swierczek SI, Bennett B, Holz RC. Inorg. Chem. 2005;44:1160–1162. doi: 10.1021/ic0487934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mullins CS, Grapperhaus CA, Kozlowski PM. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2006;11:617–625. doi: 10.1007/s00775-006-0109-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ashby MT, Enemark JH, Lichtenberger DL. Inorg. Chem. 1988;27:191–197. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.