Abstract

Interactions between cells and extracellular matrix (ECM), in particular the basement membrane (BM), are fundamentally important for the regulation of a wide variety of physiological and pathological processes. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) play critical roles in ECM remodeling and/or regulation of cell-ECM interactions because of their ability to cleave protein components of the ECM. Of particular interest among MMPs is stromelysin-3 (ST3), which was first isolated from a human breast cancer and also shown to be correlated with apoptosis during development and invasion of tumor cells in mammals. We have been using intestinal remodeling during thyroid hormone (TH)-dependent amphibian metamorphosis as a model to study the role of ST3 during postembryonic tissue remodeling and organ development in vertebrates. This process involves complete degeneration of the tadpole or larval epithelium through apoptosis and de novo development of the adult epithelium. Here, we will first summarize expression studies by us and others showing a tight spatial and temporal correlation of the expression of ST3 mRNA and protein with larval cell death and adult tissue development. We will then review in vitro and in vivo data supporting a critical role of ST3 in TH-induced larval epithelial cell death and ECM remodeling. We will further discuss the potential mechanisms of ST3 function during metamorphosis and its broader implications.

Keywords: Thyroid hormone receptor, extracellular matrix, matrix metalloproteinase, Xenopus laevis, metamorphosis, apoptosis

1. INTRODUCTION

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is a complex structure composed of many proteins and other macromolecules (Hay, 1991; Timpl & Brown, 1996). The ECM serves as a structural support media for the cells that it surrounds and is essential for maintaining the three-dimensional structure of the tissue or organ. The ECM can also affect cell function by interacting directly with cells through cell surface ECM receptors, especially the integrins (Brown & Yamada, 1995; Damsky & Werb, 1992; Schmidt et al., 1993) or by modulating the availability and levels of many signaling molecules such as growth factors that are stored in the ECM (Vukicevic et al., 1992; Werb et al., 1996). Since most cells in multicellular organisms such as vertebrates are surrounded by ECM, alterations in the ECM can influence cell fate and behavior by affecting cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions (Hay, 1991; Ruoslahti & Reed, 1994). The critical roles of ECM are reflected by the fact that ECM degradation and remodeling always accompany tissue remodeling, organogenesis, and pathogenesis throughout the animal kingdom.

ECM remodeling and degradation is largely due to the proteolytic action of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). MMPs are extracellular or membrane-bound enzymes (Alexander & Werb, 1991; Barrett et al., 1998; Birkedal-Hansen et al., 1993; McCawley & Matrisian, 2001; Nagase, 1998; Parks & Mecham, 1998; Pei, 1999). This large family of proteolytic enzymes can be divided into 5 subfamilies, collagenases, gelatinases, stromelysins, membrane-type MMPs, and others. MMPs consist of multiple domains, including from the N to C-terminus the pre- and pro-peptides, a catalytic domain, a hinge region, and in most MMPs, the hemopexin-like domain. In addition, gelatinase A (MMP2) and B (MMP9) also contain the fibronectin-like domain within the catalytic domain, and membrane type-MMPs have a transmembrane or membrane-attachment domain in the C-terminus (Fig. 1). MMPs are synthesized as preenzymes and the pre-peptide is cleaved upon secretion into the ECM as proenzymes with a few exceptions such as ST3 and membrane type-MMPs. The pro-enzymes are enzymatically inactive and are activated extracellularly through proteolytic removal of the propeptide (Barrett et al., 1998; Birkedal-Hansen et al., 1993; Kleiner & Stetler-Stevenson, 1993; Murphy et al., 1999; Nagase, 1998; Nagase et al., 1992). ST3 and membrane type-MMPs are activated intracellularly through a furin-dependent process and are thus secreted or attached to the plasma membrane as the mature enzymes, respectively (Fig. 1) (McCawley & Matrisian, 2001; Pei & Weiss, 1995; Sato & Seiki, 1996). The mature or activated MMPs have different but often overlapping substrate specificities (Barrett et al., 1998; McCawley & Matrisian, 2001; Overall, 2002; Uria & Werb, 1998). Collectively, they are capable of cleaving all protein components of the extracellular matrix. In addition, MMPs are capable of degrading non-ECM extracellular or membrane-bound proteins such as pro-MMPs, pro-growth factors, proteinase inhibitors, and cell surface proteins, etc. (Barrett et al., 1998; McCawley & Matrisian, 2001; Overall, 2002; Uria & Werb, 1998). Thus, MMPs may influence cell behavior and tissue development through both ECM remodeling and other mechanisms.

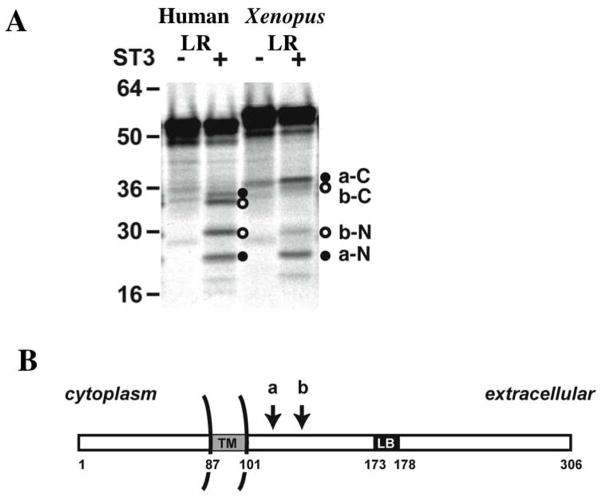

Fig. 1.

Structure of ST3. (A) ST3 protein. Like most MMPs, ST3 contains four domains. These are the pre- and pro-peptides, and catalytic and hemopexin-like domains from N- to C-terminus, respectively. A conserved peptide sequence is present in the propeptide where a C residue (underlined) is involved in coordination with the catalytic Zn atom in the inactive proenzyme. In the catalytic domain, a conserved region contains three H residues (underlined) that coordinate with the catalytic Zn atom. Like membrane type-MMPs, ST3 contains an RXKR sequence for furin-dependent intracellular activation.

(B) ST3 gene. The hinge region and the hemopexin-like domain of ST3 are encoded by only 4 exons instead of 6 exons as in other MMPs (Anglard et al., 1995; Li et al., 1998; Wei & Shi, 2005). The individual exons are shown as bars. The dotted bars indicate the coding region and the open bars represent the 5′- and 3′-UTRs. The individual domains of the coding region are indicated on the top.

We have been using frog metamorphosis as a model to study MMP function in vivo. Frog development takes place in two phases. Its embryogenesis produces a free living, aquatic, and often herbivorous tadpole. After a growth period, the tadpole undergoes metamorphosis that changes essentially every organ of the animal to produce, in vast majority of the cases, a terrestrial carnivorous frog in a process that is entirely dependent upon thyroid hormone (TH) (Shi, 1999). Molecular analysis has revealed that a number of MMP genes are induced by TH either directly or indirectly during metamorphosis. They include Rana catesbeiana collagenase 1 (MMP1) (Oofusa et al., 1994), Xenopus laevis stromelysin-3 (ST3 or MMP11), gelatinase A (MMP2), gelatinase B (MMP9), collagenase 3 (MMP 13) and 4 (MMP18), membrane type-1-MMP1 (MMP14) (Fujimoto et al., 2006; Hasebe et al., 2006; Jung et al., 2002; Patterton et al., 1995; Shi & Brown, 1993; Stolow et al., 1996; Wang & Brown, 1993). Among them, ST3 is the only one that has been demonstrated to play an important role during metamorphosis. Here, we will review some of the studies that led to the conclusion and discuss potential mechanisms by which ST3 regulates cell fate and behaviour during development.

2. AMPHIBIAN METAMORPHOSIS AND ITS REGULATION BY TH

Amphibian metamorphosis involves drastic transformation of essential every organ and tissues of the tadpole (Dodd & Dodd, 1976; Gilbert & Frieden, 1981; Gilbert et al., 1996; Kikuyama et al., 1993; Shi, 1999; Yoshizato, 1989). During this period, some organs, such as the tail and gills, degenerate completely while others, such as the limbs, develop de novo. The majority of the organs are partially yet dramatically transformed in order to function in the frog. One such organ is the intestine. The tadpole intestine is a simple tubular organ made of mostly a monolayer of larval epithelial cells surrounded by little connective tissue or muscles (Fig. 2) (Shi & Ishizuya-Oka, 1996). As metamorphosis proceeds, the tadpole stops feeding and the larval epithelial cells of the intestine undergo apoptosis or programmed cell death. Adult epithelial cells, whose origin is yet to be determined, begin to appear as islets or nests of small cell clusters and proliferate rapidly (Amano et al., 1998; McAvoy & Dixon, 1977; Shi & Ishizuya-Oka, 1996), although a recent study on limited stages failed to detect such islets (Schreiber et al., 2005). Concurrently, cells of the connective tissue and muscles also proliferate. Toward the end of metamorphosis, these adult cells differentiate to form a multiply folded intestinal epithelium surrounded by elaborate connective tissue and thick muscle layers. In the adult epithelium, the stem cells are located in the troughs of the epithelial folds, equivalent to the crypts in mammalian intestine, while fully differentiated epithelial cells are present along the crests of the folds, equivalent to the villi in mammals.

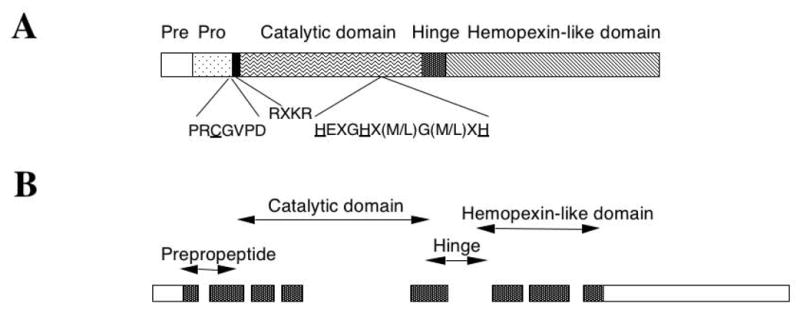

Fig. 2.

Intestinal metamorphosis is accompanied by ECM remodeling during Xenopus laevis metamorphosis. Top: Animals at the onset of metamorphic climax (stage 57), metamorphic climax (stage 60), and the end of metamorphosis (stage 66) (Nieuwkoop & Faber, 1956). Middle: Cross-sections of the intestine stained with pyronin-Y (red staining) and methyl green (blue staining) to show the morphology. The strong pyronin-Y signals observed in the clusters of cells (arrows) at metamorphic climax indicate islets of proliferating adult epithelial cells. Bottom: The ECM that separates epithelium and connective tissue is thin before and after metamorphosis (arrow heads), and becomes thicker at the metamorphic climax (double-headed arrow). LE: larval/tadpole epithelium, AE: adult epithelium, CT: connective tissue, MU: muscles, I: islets (proliferating adult epithelial cells), bl: basal lamina or basement membrane.

All changes during amphibian metamorphosis are controlled by essentially a single hormone, TH (Dodd & Dodd, 1976; Gilbert & Frieden, 1981; Gilbert et al., 1996; Kikuyama et al., 1993; Shi, 1999; Yoshizato, 1989). TH effects metamorphic changes by regulating gene transcription through thyroid hormone receptors (TRs) (Buchholz et al., 2003; Buchholz et al., 2004; Schreiber et al., 2001). Thus, an easy means to investigate the molecular mechanisms governing the metamorphic transformations in various organs is to first isolate genes regulated by TR during metamorphosis. This led to the discovery that ST3 and several other MMPs are either directly or indirectly upregulated by TR during metamorphosis (Berry et al., 1998a; Berry et al., 1998b; Damjanovski et al., 1999; Ishizuya-Oka et al., 1996; Jung et al., 2002; Oofusa et al., 1994; Patterton et al., 1995; Shi & Brown, 1993; Shi et al., 2001; Stolow et al., 1996; Wang & Brown, 1993).

3. A ROLE OF ECM REMODELING DURING INTESTINAL METAMORPHOSIS

The activation of MMP genes during metamorphosis argues for a role of ECM remodeling in the regulation of cell fate and behaviour by TH. A number of studies have indeed provided evidence to support this. First, the ECM underlying the major tissue of the intestine, the basement membrane or basal lamina, is remodelled during metamorphosis. In premetamorphic tadpoles and postmetamorphic frogs, this ECM is a thin but continuous layer (Fig. 2). During metamorphosis, as the intestine shortens (by as much as 10 fold in the small intestine), it becomes much thicker and multiply folded (Fig. 2) (Ishizuya-Oka & Shimozawa, 1987; Murata & Merker, 1991; Shi & Ishizuya-Oka, 1996). This is likely in part due to the expression of a limited number of MMP genes, which allows remodeling but not complete degradation of all ECM proteins. The contraction of the small intestine, which is needed to ensure the remaining live larval epithelial cells cover the entire luminal surface of the intestine, leads to the folding and thickening of the ECM. Second, a role of ECM in regulating cellular response to TH has been directly supported by studies using primary cultures of tadpole intestinal cells. When the epithelial and fibroblastic cells were isolated from premetamorphic tadpole intestine and cultured in vitro on plastic dishes, TH treatment led to enhanced DNA synthesis in both cell types and at same time caused the epithelial cells but not the fibroblasts to undergo apoptosis (Su et al., 1997a; Su et al., 1997b), mimicking the events during metamorphosis in intact animals. When the dishes were coated with ECM proteins such as laminin, collagen, and fibronectin, TH-induced epithelial cell death was inhibited (Su et al., 1997b). Although the result does not necessarily indicate that these ECM proteins play a protective role against TH-induced cell death in vivo, they do support the view that ECM remodeling will alter cell-ECM interactions and thus influence epithelial cells’ response to TH.

4. MOLECULAR AND BIOCHEMICAL PROPERTIES OF STROMELYSIN-3

ST3 (MMP11) was originally isolated as a breast cancer associated gene (Basset et al., 1990). While its primary structure resembles most MMPs, ST3 has several interesting and unique properties. First, it is one of the very few MMPs that are secreted directly in the activated or mature form due to intracellular activation through the furin recognition motif (RXKR) in the propeptide (Fig. 1) (Pei & Weiss, 1995). Second, in vitro, ST3 has only a very weak activity toward ECM proteins compared to other MMPs, although it has a strong activity against non-ECM proteins α1-proteinase inhibitor and IGFBP-1 (Manes et al., 1997; Murphy et al., 1993; Pei et al., 1994). Third, the ST3 gene appears to have evolved differently as it has a unique intron/exon organization in the hemopexin-like domain that is conserved from human (Anglard et al., 1995), mouse (Ludwig et al., 2000), to frog (Li et al., 1998). The hinge region and the hemopexin-like domain are encoded by 4 exons in ST3 instead of 6 in other MMPs. Finally, it has been reported that alternative splicing and promoter usage of the human ST3 gene generate a transcript encoding an intracellular active MMP (Lu et al., 2002). These findings suggest that ST3 have distinct functions compared to other MMPs.

5. DEVELOPMENTAL AND THYROID HORMONE-DEPENDENT REGULATION OF STROMELYSIN-3 EXPRESSION

ST3 was the first Xenopus laevis MMP gene that was isolated as a TH response gene through subtractive screening in both the intestine and tail (Patterton et al., 1995; Shi & Brown, 1993; Wang & Brown, 1993). Subsequently, several other MMPs, including collagenase-3 and -4, gelatinase-A and -B, and membrane type 1-MMP, have also been shown to be upregulated during intestinal remodeling and/or tail resorption in Xenopus laevis (Fujimoto et al., 2006; Hasebe et al., 2006; Jung et al., 2002; Patterton et al., 1995; Stolow et al., 1996; Wang & Brown, 1993). Interestingly, among these MMPs, only ST3 and one of the two gelatinase-B genes have been shown to be directly upregulated by TH through TRs as its upregulation by TH is independent of new protein synthesis (Fujimoto et al., 2006; Patterton et al., 1995; Shi & Brown, 1993; Wang & Brown, 1993), although collagenase 1 gene in Rana catesbeiana is also a direct target genes of TR (Oofusa & Yoshizato, 1996). Promoter analysis has revealed that indeed Rana collagenase 1, Xenopus ST3, and one of the two gelatinase B genes contain TH response elements in their promoter regulatory regions (Fu et al., 2006; Fujimoto et al., 2006; Li et al., 1998; Oofusa & Yoshizato, 1996).

Consistent with this regulation mechanism, ST3 is the first one to be upregulated in the intestine during natural metamorphosis with its mRNA levels upregulated before the onset of epithelial cell death in the intestine (by stage 58), while the other MMPs are upregulated at or after stage 60 when cell death has begun (Hasebe et al., 2006; Patterton et al., 1995; Stolow et al., 1996). Its mRNA level remains high at the climax of metamorphosis when larval cells die through apoptosis and adult cells proliferate. By stage 64, when larval epithelial cell death is completed and adult epithelial cell differentiation takes place, there is little ST3 mRNA present in the intestine. In contrast, the expression of collagenases 3 and 4, gelatinase A, and membrane type 1-MMP is upregulated later and to a lower degree, The only exception is one of the two gelatinase B genes, which has similar temporal and TH-dependent regulation as ST3 (Fujimoto et al., 2006).

The expression of ST3 is also correlated spatially with cell death during metamorphosis. Its mRNA and protein have been shown to be expressed in the fibroblasts of the connective tissue underlying the larval epithelium in the metamorphosing intestine (Ishizuya-Oka et al., 1996; Ishizuya-Oka et al., 2000; Patterton et al., 1995), similar to other MMPs (Damjanovski et al., 1999; Hasebe et al., 2006). In addition, high levels of ST3 mRNA are also present in the connective tissue underlying the apoptotic skin epidermis and surrounding the dying muscle cells in the resorbing tail (Berry et al., 1998b; Damjanovski et al., 1999). These results suggest that ST3 may play a role in cell fate regulation by facilitating TH-induced larval epithelial cell death, while most other MMPs may have a role after cell death has begun, such as removal or remodeling the ECM around the dying cells.

6. A ROLE OF ST3 IN ECM REMODELING AND CELL FATE DETERMINATION

To investigate whether ST3 indeed plays a role during intestinal remodeling, we first made use of the ability to induce intestinal remodeling in organ cultures of premetamorphic intestine by simply adding physiological concentrations of TH (Ishizuya-Oka & Shimozawa, 1991) and the fact that ST3 is a secreted protease, whose function may thus be blocked with inhibitors added to the organ culture medium. When a synthetic MMP inhibitor that can inhibit multiple MMPs was added to the organ culture medium, it inhibited TH-induced larval epithelial cell death (Ishizuya-Oka et al., 2000). To specifically inhibit ST3 function, we generated a polyclonal antibody against the catalytic domain of Xenopus laevis ST3 and found that this antibody could block the cleavage of an in vitro substrate by ST3 (Amano et al., 2004). When this functional blocking polyclonal antibody was added to the organ culture medium, it too inhibited TH-induced epithelial cell death when assayed after 3 days of culturing (Ishizuya-Oka et al., 2000). Interestingly, at this time point, ECM remodeling induced by TH was also inhibited. These results suggest that ST3 plays a critical role in both ECM remodeling and larval epithelial cell death. After 5 days of culturing, adult epithelial cells proliferated as clusters of cells or islets that expanded three dimensionally in TH-treated organ cultures in the absence of the anti-ST3 antibody. The anti-ST3 antibody was able to block the expansion of the proliferating adult epithelial islets into the connective tissue. Instead, these TH-induced adult epithelial islets expanded only laterally along the epithelium-connective tissue interface. Thus, ST3 function appears to be critical for ECM remodeling, larval cell death, and adult cell migration but not for adult epithelial cell proliferation (Ishizuya-Oka et al., 2000).

Currently, it is impossible to carry out gene knockout or knockdown studies in tadpoles, making it difficult to assess the effect of ST3 deletion on metamorphosis. On the other hand, exogenous genes can be precociously expressed in developing tadpole through transgenesis (Kroll & Amaya, 1996). This offers an opportunity to investigate whether MMPs can affect development in vivo. Transgenic expression of Xenopus laevis ST3 and collagenase-4 as well as a mammalian membrane-type-MMP under the control of the constitutive promoter CMV causes lethality during late embryonic and early tadpole stages (Damjanovski et al., 2001). To study the effects of ST3 during metamorphosis, we therefore developed a double promoter construct to express ST3 under the control of a heat shock-inducible promoter (Fu et al., 2002) and at the same time express the green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the tadpole eyes under the control of a second promoter, the γ-crystallin promoter. This allowed us to rear wild type and transgenic tadpoles together to ensure no variation in animal growth and treatment conditions between the two groups and later identify the transgenic ones by simply examining their eyes under a fluorescent dissecting microscope. The expression of transgenic ST3 was then induced by simply treating the animals with heat shock. In agreement with the transgenic studies using the CMV promoter to drive the expression of ST3, induction of ST3 expression upon heat shock during early embryonic stages also led to lethality (Fu et al., 2002). Interestingly, induction of ST3 at tadpole stages (between stage 45 to 54) for up to a few weeks had little effect on overall growth and development (Fu et al., 2005), indicating, perhaps not surprisingly, that proper regulation of MMP function is not as critical for tadpole organ/tissue function during animal growth period as for organogenesis and tissue remodeling during embryogenesis. On the other hand, analysis of the intestine of tadpoles at stage 54 after 4 days of heat shock treatment (about 1 hr heat shock treatment per day) revealed that transgenic overexpression of the wild type ST3 induced larval epithelial apoptosis (Fu et al., 2005). This was accompanied by the activation of fibroblasts (i.e., with enriched rough endoplasmic reticulum) and cell-cell contacts between epithelial cells and fibroblasts (Fig. 3). These changes are similar to those observed during natural metamorphosis. They were not present in heat shock-treated non-transgenic animals or transgenic animals containing a catalytically inactive ST3 due to a point mutation in the catalytic domain. They were also absent in both wild type and transgenic animals without heat shock treatments. Aside from these changes in the major cell types of the intestine, the basal lamina separating the epithelium and connective tissue was also altered by the transgenic expression of ST3 but not the mutant ST3 (Fig. 3). In some areas, including areas where epithelial cells and fibroblasts contact, the basal lamina was thicker and in other areas, the basal lamina appeared to be absent. This contrasts to the thick, multiply folded basal lamina observed essentially in all sections of the small intestine during metamorphosis (Fig. 3). In addition, adult epithelial cell islets were not observed in ST3 expressing transgenic animals. These findings suggest that ST3 expression alone is sufficient to induce some but not all TH-induced metamorphic program in the intestine (Fu et al., 2005), a conclusion clearly not surprising given that ST3 is only one of the many direct TR target genes that are normally induced by TH during intestinal remodeling. Nonetheless, the in vitro and in vivo studies complement each other and support a critical role of ST3 in ECM remodeling and larval epithelial cell death during intestinal metamorphosis.

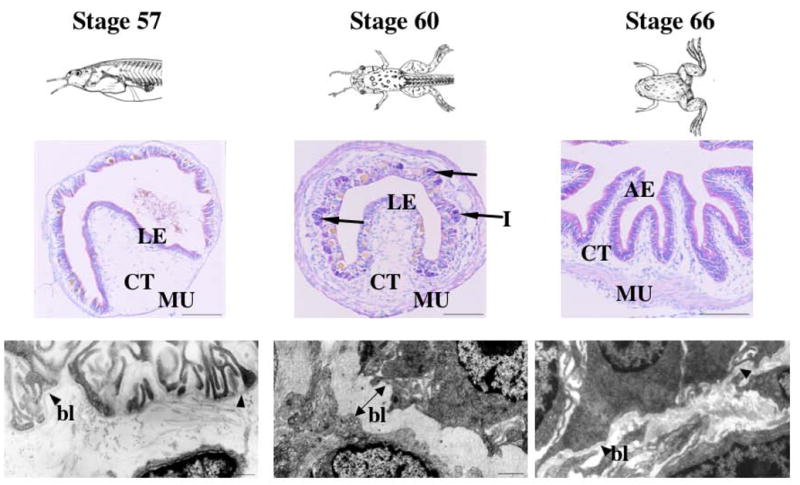

Fig. 3.

Transgenic overexpression of ST3 leads to basal lamina alteration and establishment of direct contacts between epithelial cells and fibroblasts. The intestines from wild type tadpoles at metamorphic climax (stage 61) and stage 54 wild type or transgenic tadpoles after 4 days of heat shock treatment to induce the expression of transgenic ST3 were isolated and analyzed under an electron microscope (the transgene was under the control of a heat shock inducible promoter).

(A and a). A thin and continuous basal lamina (bl, arrow heads) separates the epithelium from the connective tissue in the intestine of stage 54 wild type tadpoles with heat shock treatment, similar to wild type animals without heat shock. Panel a shows the basal lamina in the boxed region of A at a higher magnification.

(B, b). The basal lamina becomes amorphous or absent in the intestine in transgenic tadpoles expressing ST3 after heat shock treatment. Furthermore, overexpression of ST3 led to the activation of fibroblasts just beneath the epithelium, as reflected by the presence of well-developed rough endoplasmic reticulum (rER) in these cells. Panel b shows the boxed region in panel B revealing the lack of basal lamina in this region of the ST3 transgenic tadpole.

(C). Epithelial cell-fibroblast contacts are present in tadpoles overexpressing ST3 but not in wild type at stage 54.

(D). The basal lamina (double-headed arrow) becomes much thicker at the climax of metamorphosis (stage 61), when the fibroblasts are also activated as shown by the presence of well-developed rER. Ep: epithelial cell; Fb: fibroblast, bl: basal lamina; rER: rough endoplasmic reticulum. Bar: 1 μm. See (Fu et al., 2005) for more details.

7. MECHANISMS OF ST3 FUNCTION DURING METAMORPHOSIS

As indicated above, ST3 has distinct molecular and biochemical properties. Compared to essentially all other MMPs, ST3 has much weaker activities toward known ECM proteins but much higher activities toward a few non-ECM proteins such as α1-protease inhibitor, at least in vitro (Manes et al., 1997; Murphy et al., 1993; Pei et al., 1994). Although it is possible that the in vivo environment may enable ST3 to cleave ECM proteins just as efficient as other MMPs, the in vitro studies suggest that ST3 may likely function by cleaving non-ECM proteins. As the first step of ST3 function is the binding to its substrate, we carried out a yeast-two-hybrid screen to isolate proteins that bind to ST3. This led to the identification of the 67 kd laminin receptor (LR) as a potential substrate of ST3 (Amano et al., 2005a; Amano et al., 2005b). LR is synthesized as a 37 kd precursor protein. The vast majority of the precursor proteins are localized intracellularly and may be involved in translational regulation (Ardini et al., 1998; Auth & Brawerman, 1992). A small fraction of the precursor proteins are inserted in the plasma membrane and become the 67 kd LRs through possibly heterodimerization and/or posttranslational modifications (Buto et al., 1998; Castronovo et al., 1991; Landowski et al., 1995; Malinoff & Wicha, 1983; Menard et al., 1997; Rao et al., 1983; Starkey et al., 1999) (for simplicity, both the precursor and membrane bound form are referred as LR thereafter). In vitro, purified Xenopus ST3 catalytic domain can cleave E. coli produced, full length Xenopus laevis LR efficiently, with the activity slightly lower than that of the cleavage of α1-protease inhibitor by ST3 (Amano et al., 2005b). Importantly, the cleavage occurs at two sites located between the transmembrane domain and laminin binding sequence in the extracellular half of the protein (Fig. 4) (Amano et al., 2005b). Furthermore, several other MMPs cleave LR outside of the region between the transmembrane domain and laminin binding sequence (Amano et al., 2005b), suggesting that ST3 may be unique in its ability to cleave LR to alter cell-laminin interaction.

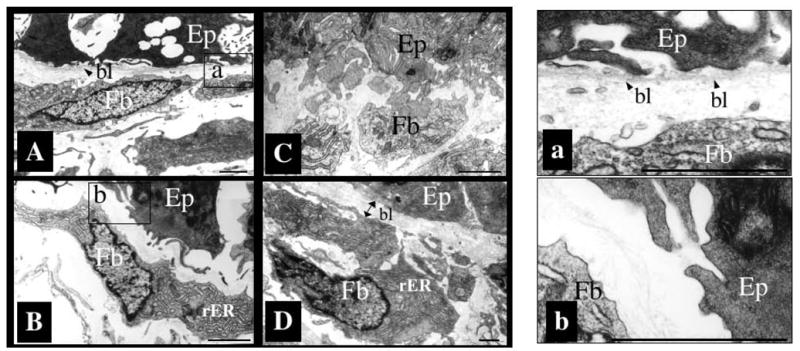

Fig. 4.

ST3 cleaves both human and Xenopus LR between the transmembrane domain (TM) and laminin binding sequence (LB). (A) ST3 cleaves human LR at the same sites as in Xenopus LR. 35S labeled full-length human and Xenopus LR were synthesized in vitro and digested with purified ST3 catalytic domain in vitro. Note that N-terminal cleavage products (a-N and b-N) of human and Xenopus LR are of the same sizes whereas the full-length protein and C-terminal cleavage products of human LR were smaller than the corresponding ones in Xenopus due to length divergence.

(B) Schematic diagram of LR localization on cell surface with the two ST3 cleavage sites indicated by two arrows (see (Amano et al., 2005b) for details).

To investigate if LR is cleaved by ST3 during intestinal metamorphosis, we have analyzed the expression of LR mRNA and protein during metamorphosis. Both LR mRNA and protein are expressed fairly constantly in the intestine during development (Amano et al., 2005a), in contrast to the metamorphosis-specific expression of ST3. Interestingly, LR fragments of the sizes expected from ST3 cleavage are present in the intestine at the climax of metamorphosis when ST3 is highly expressed, whereas little such fragments are present in pre- or post-metamorphic intestine (Fig. 5) (Amano et al., 2005a). More importantly, transgenic expression of ST3 in premetamorphic tadpoles leads to the formation of these fragments in the absence of TH (Fig. 5) (Amano et al., 2005a). These results suggest that LR is an in vivo substrate of ST3 during intestinal remodeling.

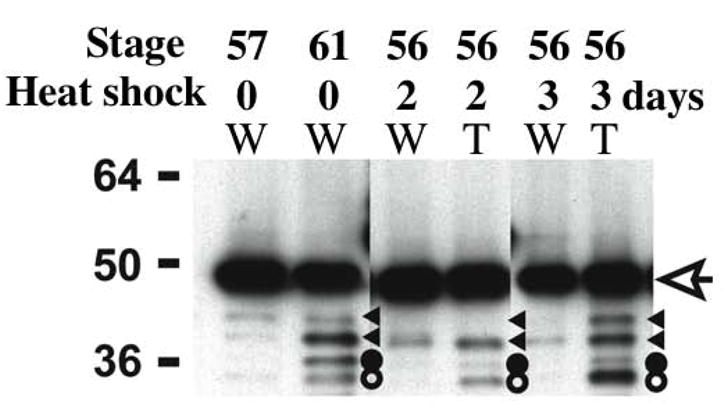

Fig. 5.

ST3 degrades LR in the intestine during metamorphosis. LR is degraded in the intestine at the climax of metamorphosis and in the intestine of premetamorphic transgenic tadpoles overexpressing ST3. Transgenic animals (T) and non-transgenic siblings (W) at stage 56 were treated with or without heat shocked daily in the same tank. Two or three days later, the intestines were isolated. Total protein was isolated from these intestines as well as from the intestines of tadpoles at stage 57, prior to intestinal metamorphosis, or stage 61, at the climax of intestinal metamorphosis. The proteins were subjected to Western blotting with anti-Xenopus LR antibody. The open arrow indicates full length LR. The triangles, and solid and open circles indicate degradation products. The larger bands (triangles) were occasionally observed in different sample preparations in tadpoles at different stages but the bands indicated by the circles were found at much higher levels in metamorphosing intestine or in animals expressing transgenic ST3 (see (Amano et al., 2005a) for details).

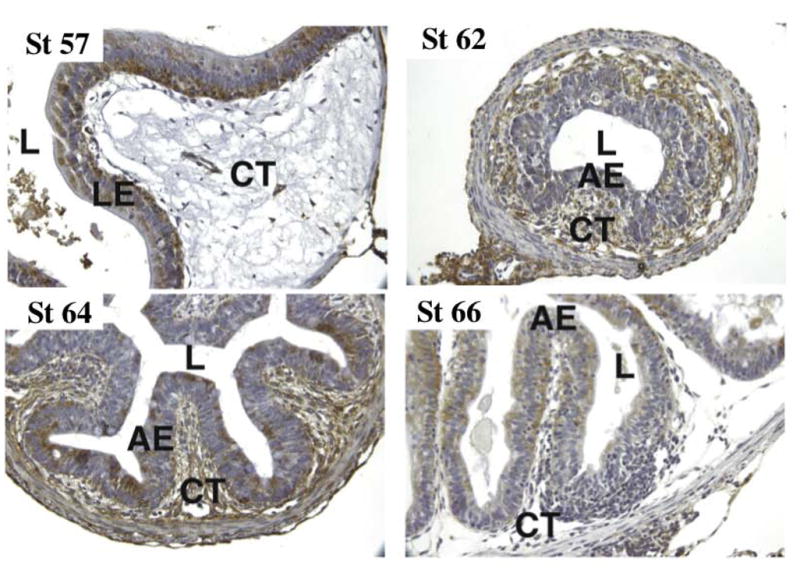

Although LR is constitutively expressed during intestinal remodeling, immunohistochemical analysis has revealed that LR is highly expressed in the differentiated epithelial cells in premetamorphic intestine with little expression in the connective tissue (Fig. 6) (Amano et al., 2005a). As intestinal metamorphosis proceeds, LR expression increases in the connective tissue but decreases in the dying larval epithelial cells. There is no detectable signal in the proliferating adult epithelial cells. As these cells differentiate, they begin to express LR. These results suggest that LR expression on the cell surface may be important for the survival and/or maintenance of the differentiated state of the intestinal epithelial cells. Thus, one mechanism of ST3 function may be that the cleavage of LR on larval epithelial cells by ST3 reduces epithelial cell-ECM interaction, thus facilitating larval epithelial cell death during intestinal metamorphosis. Unlike the monolayer differentiated epithelial cells, the undifferentiated adult epithelial cells are not associated with the basal lamina and thus do not require LR expression. Consequently, these cells are not affected by the highly expressed ST3. The high levels of LR expression in the fibroblasts of the connective tissue during metamorphosis may be related to the role of intracellular LR in protein synthesis as the fibroblasts are highly activated with extremely rich rough endoplasmic reticulum, where abundant amount of actively translating ribosomes are present.

Fig. 6.

Tissue-dependent spatial and temporal regulation of LR expression during intestinal metamorphosis. Intestinal cross sections from tadpoles at indicated stages were immunostained with anti-Xenopus LR antibody. L, lumen; LE, larval epithelium; AE adult epithelium; CT, connective tissue. The greenish brown labeling is due to LR antibody staining and the nuclei have blue staining (see (Amano et al., 2005a) for details).

8. CONCLUSIONS

The MMP stromelysin-3 shares many similarities with other MMPs but also has several unique properties. It has little expression in adult organs under normal physiological conditions but is upregulated in a number of pathological processes such as tumor invasion (Ahmad et al., 1998; Anderson et al., 1995; Basset et al., 1997; Chenard et al., 1996; Lochter & Bissell, 1999; Muller et al., 1993; Schonbeck et al., 1999; Tetu et al., 1998) and may also be involved in tumor initiation (Masson et al., 1998; Noel et al., 2000; Noel et al., 1997). During mammalian development, ST3 is expressed in many processes involving cell migration and tissue morphogenesis, especially where cell death takes place (Alexander et al., 1996; Basset et al., 1990; Chin & Werb, 1997; Lefebvre et al., 1992; Lefebvre et al., 1995; Uria & Werb, 1998), but a physiological role of ST3 has yet to be shown in vivo due largely to the difficulty to manipulate mammalian development and separate the influence of the mother. The ability to manipulate frog metamorphosis and the external development of the tadpoles have allowed the first demonstration that ST3 is both necessary and sufficient at least for some aspects of intestinal metamorphosis. Substrate isolation and analysis has revealed that one potential mechanism for ST3 to exert its effects on intestinal remodeling is to cleave LR on the larval epithelial cells.

MMPs have long attracted the attention of researchers because of the high levels of MMP expression in cancerous but not normal tissues, raising the possibility of targeting MMP function for cancer treatment. Unfortunately, human clinical trials using MMP inhibitors have yet to produce any positive results (Coussens et al., 2002). This might be due to the fact the ECM remodeling/degradation is not the determining factor in tumor invasion and metastasis, since metastasis occurs after secondary genetic changes take place in the tumor cells. In the absence of sufficient MMP activity, tumor cells may find other means, e.g., employing other proteases, to get through the ECM barrier in order to migrate into other tissues/organs. Additional analysis of the in vivo roles of MMPs and the associated mechanisms should facilitate the development of better means for target MMPs in disease prevention and treatment. The similarity of many processes during metamorphosis to processes during postembryonic development and tissue remodeling in mammals make metamorphosis a highly valuable model for this purpose. In this regard, LR is highly conserved from frog to human and both human and Xenopus LR can be cleaved by Xenopus ST3 catalytic domain at the same two conserved sites located between the transmembrane domain and laminin binding sequence in the extracellular half of the protein (Fig. 4) (Amano et al., 2005b). In addition, LR is highly expressed in cancers (Castronovo, 1993; Hand et al., 1985; Martignone et al., 1993; Menard et al., 1997; Sanjuan et al., 1996; Sobel, 1993; Yow et al., 1988), raising the possibility that LR cleavage by ST3 may also play a role in cancer development and metastasis. Clearly, further studies of ST3 function in both frog and mammalian models are needed to fully appreciate the importance of this interesting gene and to possibly target it for human health.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH.

Abbreviations

- TH

Thyroid hormone

- TR

Thyroid hormone receptor

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- ST3

stromelysin-3

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- LR

laminin receptor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahmad A, Hanby A, Dublin E, Poulsom R, Smith P, Barnes D, Rubens R, Anglard P, Hart I. Stromelysin 3: an independent prognostic factor for relapse-free survival in node-positive breast cancer and demonstration of novel breast carcinoma cell expression. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:721–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander CM, Werb Z. Extracellular matrix degradation. In: Hay ED, editor. Cell Biology of Extracellular Matrix. New York: Plenum Press; 1991. pp. 255–302. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander CM, Hansell EJ, Behrendtsen O, Flannery ML, Kishnani NS, Hawkes SP, Werb Z. Expression and function of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors at the maternal-embryonic boundary durng mouse embryo implantation. Development. 1996;122:1723–1736. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.6.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano T, Noro N, Kawabata H, Kobayashi Y, Yoshizato K. Metamorphosis-associated and region-specific expression of calbindin gene in the posterior intestinal epithelium of Xenopus laevis larva. Dev Growth Differ. 1998;40:177–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-169x.1998.00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano T, Fu L, Sahu S, Markey M, Shi YB. Substrate specificity of Xenopus matrix metalloproteinase stromelysin-3. International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2004;14:233–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano T, Fu L, Marshak A, Kwak O, Shi YB. Spatio-temporal regulation and cleavage by matrix metalloproteinase stromelysin-3 implicate a role for laminin receptor in intestinal remodeling during Xenopus laevis metamorphosis. Dev Dyn. 2005a;234:190–200. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano T, Kwak O, Fu L, Marshak A, Shi YB. The matrix metalloproteinase stromelysin-3 cleaves laminin receptor at two distinct sites between the transmembrane domain and laminin binding sequence within the extracellular domain. Cell Research. 2005b;15:150–159. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson IC, Sugarbaker DJ, Ganju RK, Tsarwhas DG, Richards WG, Sunday M, Kobzik L, Shipp MA. Stromelysin-3 is overexpressed by stromal elements in primary non-small-cell lung cancers and regulated by retinoic acid in pulmonary fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 1995;55:4120–4126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anglard P, Melot T, Guerin E, Thomas G, Basset P. Structure and Promoter Characterization of the Human Stromelysin-3 Gene. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:20337–20344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.35.20337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardini E, Pesole G, Tagliabue E, Magnifico A, Castronovo V, Sobel ME, Colnaghi MI, Menard S. The 67-kDa laminin receptor originated from a ribosomal protein that acquired a dual function during evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 1998;15:1017–1025. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auth D, Brawerman G. A 33-kDa Polypeptide with Homology to the Laminin Receptor: Component of Translation Machinery. PNAS. 1992;89:4368–4372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett JA, Rawloings ND, Woessner JF. Handbook of proteolytic enzymes. NY: Academic Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Basset P, Bellocq JP, Wolf C, Stoll I, Hutin P, Limacher JM, Podhajcer OL, Chenard MP, Rio MC, Chambon P. A novel metalloproteinase gene specifically expressed in stromal cells of breast carcinomas. Nature. 1990;348:699–704. doi: 10.1038/348699a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basset P, Bellocq JP, Lefebvre O, Noel A, Chenard MP, Wolf C, Anglard P, Rio MC. Stromelysin-3: a paradigm for stroma-derived factors implicated in carcinoma progression. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1997;26:43–53. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(97)00010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry DL, Rose CS, Remo BF, Brown DD. The expression pattern of thyroid hormone response genes in remodeling tadpole tissues defines distinct growth and resorption gene expression programs. Dev Biol. 1998a;203:24–35. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.8975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry DL, Schwartzman RA, Brown DD. The expression pattern of thyroid hormone response genes in the tadpole tail identifies multiple resorption programs. Dev Biol. 1998b;203:12–23. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.8974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkedal-Hansen H, Moore WGI, Bodden MK, Windsor LT, Birkedal-Hansen B, DeCarlo A, Engler JA. Matrix metalloproteinases: a review. Crit Rev in Oral Biol and Med. 1993;4:197–250. doi: 10.1177/10454411930040020401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KE, Yamada KM. The role of integrins during vertebrate development. Seminars in Develop Biol. 1995;6:69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz DR, Hsia VSC, Fu L, Shi YB. A dominant negative thyroid hormone receptor blocks amphibian metamorphosis by retaining corepressors at target genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:6750–6758. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.19.6750-6758.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz DR, Tomita A, Fu L, Paul BD, Shi YB. Transgenic analysis reveals that thyroid hormone receptor is sufficient to mediate the thyroid hormone signal in frog metamorphosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9026–9037. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.20.9026-9037.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buto S, Tagliabue E, Ardini E, Magnifico A, Ghirelli C, van den Brûle F, Castronovo V, Colnaghi MI, Sobel ME, Ménard S. Formation of the 67-kDa laminin receptor by acylation of the precursor. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 1998;69:244–251. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(19980601)69:3<244::aid-jcb2>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castronovo V, Taraboletti G, Sobel ME. Functional domains of the 67-kDa laminin receptor precursor. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:20440–20446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castronovo V. Laminin receptors and laminin-binding proteins during tunor invasion and matastasis. Invasion Metastasis. 1993;13:1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenard MP, OSiorain L, Shering S, Rouyer N, Lutz Y, Wolf C, Basset P, Bellocq JP, Duffy MJ. High levels of stromelysin-3 correlate with poor prognosis in patients with breast carcinoma. International Journal of Cancer. 1996;69:448–451. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19961220)69:6<448::AID-IJC5>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin JR, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases regulate morphogenesis, migration and remodeling of epithelium, tongue skeleta muscle and cartilage in the mandibular arch. Development. 1997;124:1519–1530. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.8.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coussens LM, Fingleton BM, Matrisian LM. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors and cancer: Trials and tribulations. Science. 2002;295:2387–2392. doi: 10.1126/science.1067100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damjanovski S, Ishizuya-Oka A, Shi YB. Spatial and temporal regulation of collagenases-3, -4, and stromelysin - 3 implicates distinct functions in apoptosis and tissue remodeling during frog metamorphosis. Cell Res. 1999;9:91–105. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damjanovski S, Amano T, Li Q, Pei D, Shi YB. Overexpression of Matrix Metalloproteinases Leads to Lethality in Transgenic Xenopus Laevis: Implications for Tissue-Dependent Functions of Matrix Metalloproteinases during Late Embryonic development. Dev Dynamics. 2001;221:37–47. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damsky CH, Werb Z. Signal transduction by integrin receptors for extracellular matrix: cooperative processing of extracellular information. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1992;4:772–81. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(92)90100-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd MHI, Dodd JM. The biology of metamorphosis. In: Lofts B, editor. Physiology of the amphibia. New York: Academic Press; 1976. pp. 467–599. [Google Scholar]

- Fu L, Buchholz D, Shi YB. A novel double promoter approach for identification of transgenic animals: a tool for in vivo analysis of gene function and development of gene-based therapies. Molecular Reproduction and Development. 2002;62:470–476. doi: 10.1002/mrd.10137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu L, Ishizuya-Oka A, Buchholz DR, Amano T, Shi YB. A causative role of stromelysin-3 in ECM remodeling and epithelial apoptosis during intestinal metamorphosis in Xenopus laevis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:27856–65. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413275200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu L, Tomita A, Wang H, Buchholz DR, Shi YB. Transcriptional regulation of the Xenopus laevis stromelysin-3 gene by thyroid hormone is mediated by a DNA element in the first intron. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16870–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603041200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto K, Nakajima K, Yaoita Y. One of the duplicated matrix metalloproteinase-9 genes is expressed in regressing tail during anuran metamorphosis. Develop Growth Differ. 2006;48:223–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2006.00859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert LI, Frieden E. Metamorphosis: A problem in developmental biology. 2. New York: Plenum Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert LI, Tata JR, Atkinson BG. Metamorphosis: Post-embryonic reprogramming of gene expression in amphibian and insect cells. New York: Academic Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hand PH, Thor A, Schlom J, Rao CN, Liotta LA. Expression of laminin receptor in normal and carcinomatous human tissues as defined by a monoclonal antibody. Cancer Res. 1985;45:2713–2719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasebe T, Hartman R, Matsuda H, Shi YB. Spatial and temporal expression profiles suggest the involvement of gelatinase A and membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase in amphibian metamorphosis. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;324:105–16. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-0099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay ED. Cell Biology of Extracellular Matrix. 2. New York: Plenum Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ishizuya-Oka A, Shimozawa A. Ultrastructural changes in the intestinal connective tissue of Xenopus laevis during metamorphosis. J Morphol. 1987;193:13–22. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1051930103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizuya-Oka A, Shimozawa A. Induction of metamorphosis by thyroid hormone in anuran small intestine cultured organotypically in vitro. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1991;27A:853–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02630987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizuya-Oka A, Ueda S, Shi YB. Transient expression of stromelysin-3 mRNA in the amphibian small intestine during metamorphosis. Cell Tissue Res. 1996;283:325–9. doi: 10.1007/s004410050542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizuya-Oka A, Li Q, Amano T, Damjanovski S, Ueda S, Shi YB. Requirement for matrix metalloproteinase stromelysin-3 in cell migration and apoptosis during tissue remodeling in Xenopus laevis. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:1177–88. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.5.1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung JC, Leco KJ, Edwards DR, Fini ME. Matrix metalloproteinase mediate the dismantling of mesenchymal structures in the tadpole tail during thyroid hormone-induced tail resorption. Dev Dyn. 2002;223:402–413. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuyama S, Kawamura K, Tanaka S, Yamamoto K. Aspects of amphibian metamorphosis: hormonal control. Int Rev Cytol. 1993;145:105–48. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)60426-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner DE, Jr, Stetler-Stevenson WG. Structural biochemistry and activation of matrix metalloproteases. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1993;5:891–7. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(93)90040-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroll KL, Amaya E. Transgenic Xenopus embryos from sperm nuclear transplantations reveal FGF signaling requirements during gastrulation. Development. 1996;122:3173–83. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.3173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landowski TH, Dratz EA, Starkey JR. Studies of the Structure of the Metastasis-Associated 67 kDa Laminin Binding Protein: Fatty Acid Acylation and Evidence Supporting Dimerization of the 32 kDa Gene Product To Form the Mature Protein. Biochemistry. 1995;34:11276–11287. doi: 10.1021/bi00035a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre O, Wolf C, Limacher JM, Hutin P, Wendling C, LeMeur M, Basset P, Rio MC. The breast cancer-associated stromelysin-3 gene is expressed during mouse mammary gland apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:997–1002. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.4.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre O, Regnier C, Chenard MP, Wendling C, Chambon P, Basset P, Rio MC. Developmental expression of mouse stromelysin-3 mRNA. Development. 1995;121:947–55. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.4.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Liang VCT, Sedgwick T, Wong J, Shi YB. Unique organization and involvement of GAGA factors in the transcriptional regulation of the Xenopus stromelysin-3 gene. Nucl Acids Res. 1998;26:3018–3025. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.12.3018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochter A, Bissell MJ. An odyssey from breast to bone: multi-step control of mammary metastases and osteolysis by matrix metalloproteinases. APMIS. 1999;107:128–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1999.tb01535.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu D, Mari B, Stoll I, Anglard P. Alternative splicing and promoter usage generates an intracellular stromelysin-3 isoform directly translated as an active matrix metalloproteinase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25527–25536. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202494200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig MG, Basset P, Anglard P. Multiple regulator elements in the murine stromelysin-3 promoter: Evidence for direct control by CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta and thyroid and retinoid receptors. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39981–39990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007529200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinoff HL, Wicha MS. Isolation of a cell surface receptor protein for laminin from murine fibrosarcoma cells. J Cell Biol. 1983;96:1475–1479. doi: 10.1083/jcb.96.5.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manes S, Mira E, Barbacid MD, Cipres A, FernandezResa P, Buesa JM, Merida I, Aracil M, Marquez G, Martinez C. Identification of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1 as a potential physiological substrate for human stromelysin-3. J of Biol Chem. 1997;272:25706–25712. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martignone S, Menard S, Bufalino R, Cascinelli N, Pellegrini R, Tagliabue E, Andreola S, Rilke F, Colnaghi MI. Prognostic significance of the 67-kilodalton laminin receptor expression in human breast carcinomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:398–402. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masson R, Lefebvre O, Noel A, Fahime ME, Chenard MP, Wendling C, Kebers F, LeMeur M, Dierich A, Foidart JM, Basset P, Rio MC. In vivo evidence that the stromelysin-3 metalloproteinase contributes in a paracrine manner to epithelial cell malignancy. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:1535–41. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.6.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAvoy JW, Dixon KE. Cell proliferation and renewal in the small intestinal epithelium of metamorphosing and adult Xenopus laevis. J Exp Zool. 1977;202:129–138. [Google Scholar]

- McCawley LJ, Matrisian LM. Matrix metalloproteinases: they’re not just for matrix anymore! Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2001;13:534–540. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00248-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menard S, Castronovo V, Tagliabue E, Sobel ME. New insights into the metastasis-associated 67 kD laminin receptor. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 1997;67:155–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller D, Wolf C, Abecassis J, Millon R, Engelmann A, Bronner G, Rouyer N, Rio MC, Eber M, Methlin G. Increased stromelysin 3 gene expression is associated with increased local invasiveness in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1993;53:165–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata E, Merker HJ. Morphologic changes of the basal lamina in the small intestine of Xenopus laevis during metamorphosis. Acta Anat. 1991;140:60–9. doi: 10.1159/000147038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy G, Segain JP, O’Shea M, Cockett M, Ioannou C, Lefebvre O, Chambon P, Basset P. The 28-kDa N-terminal domain of mouse stromelysin-3- has the general properties of a weak metalloproteinase. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:15435–15441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy G, Stanton H, Cowell S, Butler G, Knauper V, Atkinson S, Gavrilovic J. Mechanisms for pro matrix metalloproteinase activation. Apmis. 1999;107:38–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1999.tb01524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagase H. Cell surface activation of progelatinase A (proMMP-2) and cell migration. Cell Res. 1998;8:179–86. doi: 10.1038/cr.1998.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagase J, Suzuki K, Morodomi T, Englhild JJ, Salvesen G. Activation Mechanisms of the Precursors of Matrix Metalloproteinases 1, 2, and 3. Matrix Supple. 1992;1:237–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwkoop PD, Faber J. Normal table of Xenopus laevis. 1. Amsterdam: North Holland Publishing; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Noel A, Boulay A, Kebers F, Kannan R, Hajitou A, Calberg-Bacq CM, Basset P, Rio MC, Foidart JM. Demonstration in vivo that stromelysin-3 functions through its proteolytic activity. Oncogene. 2000;19:1605–1612. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel AC, Lefebvre O, Maquoi E, VanHoorde L, Chenard MP, Mareel M, Foidart JM, Basset P, Rio MC. Stromelysin-3 expression promotes tumor take in nude mice. J Clin Invest. 1997;97:1924–2930. doi: 10.1172/JCI118624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oofusa K, Yomori S, Yoshizato K. Regionally and hormonally regulated expression of genes of collagen and collagenase in the anuran larval skin. Int J Dev Biol. 1994;38:345–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oofusa K, Yoshizato K. Thyroid hormone-dependent expression of bullfrog tadpole collagenase gene. Roux’s Arch Dev Biol. 1996;205:241–251. doi: 10.1007/BF00365802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overall CM. Molecular determinants of metalloproteinase substrate specificity. Molecular Biotechnology. 2002;22:51–86. doi: 10.1385/MB:22:1:051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks WC, Mecham RP. Matrix metalloproteinases. New York: Academic Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Patterton D, Hayes WP, Shi YB. Transcriptional activation of the matrix metalloproteinase gene stromelysin-3 coincides with thyroid hormone-induced cell death during frog metamorphosis. Dev Biol. 1995;167:252–62. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei D, Majmudar G, Weiss SJ. Hydrolytic inactivation of a breast carcinoma cell-derived serpin by human stromelysin-3. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:25849–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei D, Weiss SJ. Furin-dependent intracellular activation of the human stromelysin-3 zymogen. Nature. 1995;375:244–7. doi: 10.1038/375244a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei D. Leukolysin/MMP25/MT6-MMP: a novel matrix metalloproteinase specifically expressed in the leukocyte lineage. Cell Res. 1999;9:291–303. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao NC, Barsky SH, Terranova VP, Liotta LA. Isolation of a tumor cell laminin receptor . Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1983;111:804–808. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(83)91370-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruoslahti E, Reed JC. Anchorage dependence, integrins, and apoptosis. Cell. 1994;77:477–8. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90209-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanjuan X, Fernandez PL, Miquel R, Munoz J, Castronovo V, Menard S, Palacin A, Cardesa A, Campo E. Overexpression of the 67-kD laminin receptor correlates with tumor progression in human colorectal carcinoma. J Pathol. 1996;179:376–380. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199608)179:4<376::AID-PATH591>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato H, Seiki M. Membrane-Type Matrix Metallproteinases (MT-MMPs) in Tumor Metastasis. J Biochem. 1996;119:209–215. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt JW, Piepenhagen PA, Nelson WJ. Modulation of epithelial morphogenesis and cell fate by cell-to-cell signals and regulated cell adhesion. Seminars in Cell Biol. 1993;4:161–73. doi: 10.1006/scel.1993.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonbeck U, Mach F, Sukhova GK, Atkinson E, Levesque E, Herman M, Graber P, Basset P, Libby P. Expression of stromelysin-3 in atherosclerotic lesions: Regulation via CD40-CD40 ligand signaling in vitro and in vivo. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1999;189:843–853. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.5.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber AM, Das B, Huang H, Marsh-Armstrong N, Brown DD. Diverse developmental programs of Xenopus laevis metamorphosis are inhibited by a dominant negative thyroid hormone receptor. PNAS. 2001;98:10739–10744. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191361698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber AM, Cai L, Brown DD. Remodeling of the intestine during metamorphosis of Xenopus laevis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:3720–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409868102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi YB, Brown DD. The earliest changes in gene expression in tadpole intestine induced by thyroid hormone. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:20312–20317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi YB, Ishizuya-Oka A. Biphasic intestinal development in amphibians: Embryogensis and remodeling during metamorphosis. Current Topics in Develop Biol. 1996;32:205–235. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60429-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi YB. Amphibian Metamorphosis: From morphology to molecular biology. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Shi YB, Fu L, Hsia SC, Tomita A, Buchholz D. Thyroid hormone regulation of apoptotic tissue remodeling during anuran metamorphosis. Cell Res. 2001;11:245–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Differential expression of the 67 kDa laminin receptor in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 1993;4:311–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkey JR, Uthanyakumar S, Berglund DL. Cell surface and substrate distribution of the 67-kDa laminin-binding protein determined by using a ligand photoaffinity probe. Cytometry. 1999;35:37–47. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0320(19990101)35:1<37::aid-cyto6>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolow MA, Bauzon DD, Li J, Sedgwick T, Liang VC, Sang QA, Shi YB. Identification and characterization of a novel collagenase in Xenopus laevis: possible roles during frog development. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:1471–83. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.10.1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Y, Shi Y, Shi YB. Cyclosporin A But not FK506 Inhibits Thyroid Hormone-Induced Apoptosis in Xenopus Tadpole Intestinal Epithelium. FASEB J. 1997a;11:559–565. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.7.9212079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Y, Shi Y, Stolow M, Shi YB. Thyroid hormone induces apoptosis in primary cell cultures of tadpole intestine: cell type specificity and effects of extracellular matrix. J Cell Biol. 1997b;139:1533–1543. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.6.1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetu B, Brisson J, Lapointe H, Bernard P. Prognostic significance of stromelysin 3, gelatinase A, and urokinase expression in breast cancer. Human Pathology. 1998;29:979–985. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(98)90204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timpl R, Brown JC. Supramolecular assembly of basement membranes. BioEssays. 1996;18:123–132. doi: 10.1002/bies.950180208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uria JA, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases and their expression in mammary gland. Cell Res. 1998;8:187–94. doi: 10.1038/cr.1998.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vukicevic S, Kleinman HK, Luyten FP, Roberts AB, Roche NS, Reddi AH. Identification of multiple active growth factors in basement membrane Matrigel suggests caution in interpretation of cellular activity related to extracellular matrix components. Exp Cell Res. 1992;202:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(92)90397-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Brown DD. Thyroid hormone-induced gene expression program for amphibian tail resorption. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:16270–16278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L, Shi YB. Matrix metalloproteinase stromelysin-3 in development and pathogenesis. Histology and histopathology. 2005;20:177–85. doi: 10.14670/HH-20.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werb Z, Sympson CJ, Alexander CM, Thomasset N, Lund LR, MacAuley A, Ashkenas J, Bissell MJ. Extracellular matrix remodeling and the regulation of epithelial- stromal interactions during differentiation and involution. Kidney Int Suppl. 1996;54:S68–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizato K. Biochemistry and cell biology of amphibian metamorphosis with a special emphasis on the mechanism of removal of larval organs. Int Rev Cytol. 1989;119:97–149. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)60650-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yow H, Wong JM, Chen HS, Lee C, Steele JGD, Chen LB. Increased mRNA expression of a laminin-binding protein in human colon carcinoma: Complete sequence of a full-length cDNA encoding the protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:6394–6398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.17.6394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]