Abstract

Annexin A2 is involved in multiple cellular processes, including cell survival, growth, division, and differentiation. A lack of annexin A2 makes cells more sensitive to apoptotic stimuli. Here, we demonstrate a potential mechanism for apoptotic stimuli-induced annexin A2 cleavage, which contributes to cell cycle inhibition and apoptosis. Annexin A2 was persistently expressed around the proliferative but not the necrotic region in BALB/c nude mice with human lung epithelial carcinoma cell A549-derived tumors. Knockdown expression of annexin A2 made cells susceptible to either serum withdrawal-induced cell cycle inhibition or cisplatin-induced apoptosis. Under apoptotic stimuli, annexin A2 was time-dependently cleaved. Mechanistic studies have shown that protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A)-activated glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3 is essential for this process. Therefore, inhibiting GSK-3 reversed serum withdrawal-induced cell cycle inhibition and cisplatin-induced apoptosis. Furthermore, inhibiting serine proteases blocked apoptotic stimuli-induced annexin A2 cleavage. Bax activation and Mcl-1 destabilization, which is regulated by PP2A and GSK-3, caused annexin A2 cleavage via an Omi/HtrA2-dependent pathway. Taking these results together, we conclude that GSK-3 and Omi/HtrA2 synergistically cause annexin A2 cleavage and then cell cycle inhibition or apoptosis.

INTRODUCTION

Annexin A2 (also called p36, calpactin I, lipocortin II, chromobindin VIII, and placental anticoagulant protein IV), a 36-kDa protein of the annexin family, exists as a monomer or a heterotetramer with two S100A10 (also called p11 and S100 calcium-binding protein A10) genes (Gerke and Moss, 2002; Gerke et al., 2005). Physiologically, annexin A2 is expressed in secreted, membrane-bound, cytoplasmic, and nuclear forms. The N terminus of annexin A2 contains the p11-binding site (Johnsson et al., 1988) and is phosphorylated by pp60src (Tyr23) and protein kinase C (Ser25) (Gould et al., 1986). The C-terminus of annexin A2 contains heparin- and plasminogen-binding sites (Hajjar et al., 1994; Kassam et al., 1997). The core domain contains four annexin repeats, each of which contains an α-helix domain for calcium binding (Gerke and Moss, 2002; Gerke et al., 2005).

Intracellular annexin A2 is calcium-dependently activated and conformationally changed, forms a heterotetramer with p11, and then shows a high affinity for phospholipid binding (Johnsson et al., 1988; Gerke et al., 2005). Under heat shock, a Src-like kinase causes annexin A2 phosphorylation and heterotetramer externalization (Deora et al., 2004), the biological effects of which remain unidentified. Membrane externalization of annexin A2 in phagocytes is required for apoptotic cell clearance (Fan et al., 2004). In addition, intracellular annexin A2 is involved in lipid raft formation and cytoskeleton reorganization (Oliferenko et al., 1999; Babiychuk and Draeger, 2000; Babiychuk et al., 2002; Singh et al., 2004). Thus, annexin A2 is pivotal in exocytosis (Sarafian et al., 1991) and endocytosis (Emans et al., 1993; Morel and Gruenberg, 2007). Genetic knockdown of annexin A2 inhibits cell division and proliferation (Chiang et al., 1999). Annexin A2 down-regulation is related to p53-mediated apoptotic pathways (Huang et al., 2008). However, annexin A2 overexpression does not reverse growth factor withdrawal-induced cell death (Matsunaga et al., 2004). Notably, annexin A2 is overexpressed in acute myeloid leukemia (Menell et al., 1999), brain tumors (Roseman et al., 1994), breast cancer (Sharma et al., 2006), pancreatic cancer (Esposito et al., 2006), and gastric cancer (Emoto et al., 2001). Mechanistically, it is a receptor for tissue plasminogen activator and then activates plasminogen (Hajjar and Krishnan, 1999; Sharma et al., 2006). Thus, extracellular annexin A2 activates the fibrinolytic system associated with cancer metastasis. Therefore, annexin A2 has diverse functions.

Annexin A2 expressed on smooth muscle cell membrane can be terminated by calpain-mediated proteolytic cleavage (Babiychuk et al., 2002). In chaperone-induced autophagy, annexin A2 is cleaved in human lung fibroblasts via a lysosome pathway (Cuervo et al., 2000). When interleukin (IL)-3 is withdrawn, annexin A2 is time-dependently degraded (Matsunaga et al., 2004); however, the mechanism is not understood. IL-3 withdrawal causes ubiquitinylation-mediated degradation of Mcl-1, a member of the Bcl-2 family, through a mechanism involving a glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3-mediated postmodification (Maurer et al., 2006). In addition to Mcl-1, proapoptotic Bax also the target of GSK-3 (Linseman et al., 2004) and may cause mitochondrial destabilization and apoptosis. Under normal growth conditions, the phosphatidylinositol (PI)3-kinase/Akt pathway is active and negatively regulates its downstream substrate GSK-3 (Cross et al., 1995). Protein phosphatase (PP)2A positively regulates GSK-3 directly via dephosphorylation and indirectly by down-regulating PI3-kinase/Akt signaling (Lin et al., 2007). Actually, PP2A is activated under serum withdrawal (Chen et al., 1992, 1994). In the present study, we investigated the potential effects of PP2A/Akt/GSK-3 signaling and the mitochondrial pathway on annexin A2 stabilization in cells under serum withdrawal and anticancer drug treatment. The implications of GSK-3–mediated annexin A2 destabilization in serum withdrawal-induced cell cycle inhibition and anticancer drug-induced apoptosis also were investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Cultures and Reagents

CL1-5 human lung epithelial adenocarcinoma cells, A431 human epidermoid carcinoma cells, and CaSki human cervical squamous cell carcinoma cells were kindly provided by Dr. P. C. Yang (Institute of Internal Medicine, National Taiwan University, Taiwan), Dr. H. S. Huang (Institute of Medical Technology and Biotechnology, National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan); and Dr. M. R. Shen (Department of Pharmacology, National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan), respectively. A549 human lung epithelial adenocarcinoma cells, A431, and CaSki cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum. CL1-5 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum. They were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2. All the cell culture media and reagents were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). For serum withdrawal, cells were cultured in medium without 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum. GSK-3 inhibitor SB415286, PP2A inhibitor okadaic acid (OA), and Src inhibitor PP2 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (Me2SO). PI3-kinase inhibitor LY294002 was purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO) and dissolved in Me2SO. Omi/HtrA2 inhibitor Ucf-101 and cathepsin B inhibitor benzyloxycarbonyl-Phe-Ala-fluoromethyl ketone (z-FA-fmk) were purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA) and dissolved in Me2SO. Serine protease inhibitor 4-(2-Aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride (AEBSF) was purchased from Fluka Biochemika (Fluka Chemical, Milwaukee, WI) and dissolved in H2O. Cathepsin D inhibitor pepstatin A (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in methanol containing 10% ethanol.

Animals and Models

The 6-wk-old progeny of BALB/c nude mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were used for the study. The mice were fed standard laboratory chow and water ad libitum in the Laboratory Animal Center of National Cheng Kung University. They were raised and cared for in a pathogen-free environment according to the guidelines set by the National Science Council, Taiwan. The experimental protocol adhered to the rules of the Animal Protection Act of Taiwan and was approved by the Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee of National Cheng Kung University. To develop a tumor model as described previously (Yeh et al., 2006), A549 cells in suspension (1 × 106 cells/0.1 ml) were injected into the peritoneal cavity of the mice. All the mice were killed on the day when the first mouse died of the induced tumor.

Western Blot Analysis

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was used to separate cell extracts, which were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA). After they had been blocked, the blots were developed with a series of antibodies as indicated. Rabbit antibodies specific for human Src and phosphorylated Src (Tyr416), Akt and phosphorylated Akt (Ser473), GSK-3α/β and phosphorylated GSK-3α/β (Ser21/Ser9), Mcl-1 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), and annexin A2 (p36) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), were used. Mouse antibodies against enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), PP2Ac, and phosphorylated PP2Ac (Tyr307) (Millipore), GSK-3β, phosphorylated GSK-3β (Ser9) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), XIAP (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich) were used. Finally, the blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) or anti-mouse IgG (Calbiochem) and developed using an ECL development kit (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL).

Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) Analysis

Total RNA was isolated using a reagent (TRIzol; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and reverse-transcribed with kits (ReveretAid first strand cDNA synthesis kit; Fermentas UAB, Vilnius, Lithuania). The cDNA was amplified using PCR with Taq polymerase (Fermentas UAB). The PCR primers, designed by the primer 3 program (Steve Rozen and Helen Skaletsky, Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, Cambridge, MA), were as follows: annexin A2 (p36)-sense, 5′-CCC CCC GGG ATG TCT ACT GTT CAC GAA ATC-3′ and annexin A2 (p36)-antisense, 5′-CGC GGA TCC GCG TCA TCT CCA CCA C-3′; p11-sense, 5′-GCA CAA AAT TTC ACC CTG AC-3′ and p11-antisense, 5′-GCA CTG GAT CTG TTT CTT CA-3′; and β-actin-sense, 5′-AGA GCT ACG AGC TGC CTG ACT-3′ and β-actin-antisense, 5′-AAA GCC ATG CCA ATC TCA TC-3′. The samples were amplified in a thermal cycler for 25 cycles; the cycling profile was 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min, with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Electrophoresis was used to analyze all PCR products, and fragment sizes were compared using a 1-kb DNA ladder (Fermentas UAB).

Short Interfering RNA (siRNA) Preparation and Gene Expression

Annexin A2 (catalog no. 29199), GSK-3α (catalog no. 29339), GSK-3β (catalog no. 35527), Bax (catalog no. 29212), and Omi/HtrA2 (catalog no. 35615) were silenced using commercialized siRNA kits (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Transfection was performed by electroporation using a pipette-type microporator (Microporator system; Digital Bio Technology, Suwon, Korea). After they had been transfected, the cells were incubated for 48 h in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C, before stimulation. A nonspecific scrambled siRNA (control siRNA-A, catalog no. 37007; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was the negative control. Plasmid pEGFP-N1 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) co-encoded human annexin A2 (p36) (pEGFP-N1-p36) was constructed. In brief, pEGFP-N1 was digested by BglII and BamHI and annealed with the PCR product of human annexin A2 (p36) from A549 cells. EGFP was fused onto the C terminus of annexin A2. For human GSK-3β and Mcl-1 overexpression, GSK-3β wild-type (pEGFP-GSK-3β), GSK-3β dominant-negative mutant (pEGFP-GSK-3β R96A), pcDNA3-HA, and pcDNA3-HA-hMcl-1 were kindly provided by Dr. P. J. Lu (Institute of Clinical Medicine, National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan) and Dr. H. F. Yang-Yen (Institute of Molecular Biology, Academia Sinica, Taiwan), respectively. For transfection, Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) reagent and 50 nM DNA plasmids were used.

Cell Cycle Analysis

Cells were resuspended and fixed by adding 1 ml of ice-cold 70% ethanol in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then stored at 4°C. Fixed cells (104/sample) were washed in PBS, incubated with propidium iodide (PI) staining solution (0.04 mg/ml PI and 0.1 mg/ml RNase A) for 30 min at room temperature, and then analyzed on a flow cytometer (FACSCalibur; BD Biosciences).

Mitochondrial Function Assay

The loss of mitochondrial transmembrane potential (ΔΨm) was determined using rhodamine 123 (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells (104/sample) were incubated with 5 μM rhodamine 123 for 30 min, washed with phosphate-buffered saline, and then immediately analyzed using flow cytometry (FACSCalibur).

Immunostaining

Cells were grown on coverslides for experiments. After the cells had been treated, they were dyed with 200 nM MitoTracker Red CMXRos (Invitrogen) for 30 min at 37°C according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cells were then fixed with methanol that contained acetic acid (3:1). Rabbit antibodies against Bax (Serotec, Oxford, United Kingdom) and Omi/HtrA2 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) were used, and then Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen) staining. The cells were then visualized using a laser-scanning confocal microscope (SPII; Leica Mikrosysteme Vertrieb, Bensheim, Germany).

Immunohistochemistry

The tumor specimens were fixed in 10% Formalin, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 5-μm-thick sections. For immunohistochemistry, the sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, incubated with 3% H2O2 in methanol for 15 min, and subjected to heat-induced antigen retrieval by boiling them for 10 min in 0.01 M sodium citrate. Subsequently, the specimens were incubated with rabbit antibodies against Ki-67 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and mouse antibody against annexin A2 (p36) (BD Biosciences) antibodies (1:100) at 4°C for 16 h and then with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen) and Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen) staining. Finally, the specimens were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The slides were then visualized using a fluorescence microscope (BX51; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance. Results are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Annexin A2 (p36) Expression Was Involved in the Cell Cycle and Survival

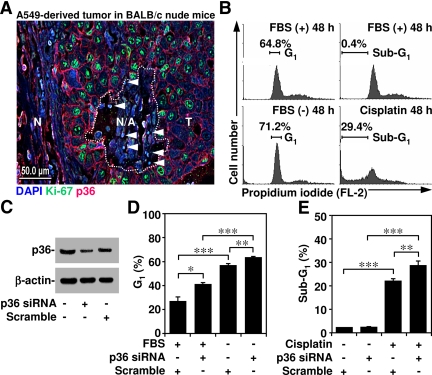

Annexin A2 regulates cell division and apoptosis (Chiang et al., 1999; Huang et al., 2008). In human lung epithelial adenocarcinoma cell A549-derived tumors, immunostaining showed that annexin A2 was largely expressed around the proliferative cells (identified using proliferative marker Ki-67 staining) but not in either the necrotic region (identified by destructive morphology) or in apoptotic cells (identified using condensed DAPI staining) (Figure 1A). We used PI staining and then flow cytometry to investigate the role of annexin A2 in the cell cycle and survival. We first confirmed that the cell cycle had been arrested in the G1 phase under serum withdrawal and that treatment with the anticancer drug cisplatin inhibited cell survival (Figure 1B). To verify the role of annexin A2, we used siRNA to silence annexin A2 in A549 cells. Western blot analysis showed that annexin A2 knockdown was more efficient than the scrambled control at down-regulating annexin 2 expression (Figure 1C). Annexin A2 knockdown cells were significantly (p < 0.05) more susceptible to serum withdrawal-induced arrest in the G1 phase (Figure 1D) as well as cisplatin-induced cell apoptosis (Figure 1E). These results indicated that annexin A2 was involved in the cell cycle and survival.

Figure 1.

Characterization of annexin A2 expression in tumors and its roles in serum withdrawal-induced cell cycle inhibition and cisplatin-induced apoptosis. (A) Tissue sections of peritoneal tumors derived from A549 cells in BALB/c nude mice were stained for annexin A2 (p36; red), Ki-67 (green), and DAPI (blue). The apoptotic cells were characterized with condensed DAPI staining (arrowheads). Bar, 50 μm. N, normal region; N/A, necrotic/apoptotic region (dotted circle); T, tumor region. (B) A549 cells (5 × 105) were cultured under serum withdrawal or normal culture conditions with cisplatin (50 μM) cotreatment for 36 h. Cell cycle stages were determined using PI staining and then flow cytometry. One each of representative histograms and the percentages of cells in the G1 or subG1 phase are shown, respectively. (C–E) A549 cells were transfected with or without annexin A2 (p36) siRNA (50 nM) for 48 h. We used Western blotting to determine annexin A2 (p36) expression. After that, cells were cultured under serum withdrawal or normal culture conditions with cisplatin (50 μM) cotreatment for 36 h. Cell cycle stages were determined using PI staining and then flow cytometry. The percentages of cells in the G1 or subG1 phase are shown as means ± SEM from three individual experiments with triplicate cultures. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

Apoptotic Stimuli Caused Annexin A2 Cleavage in Human Epithelial Cells

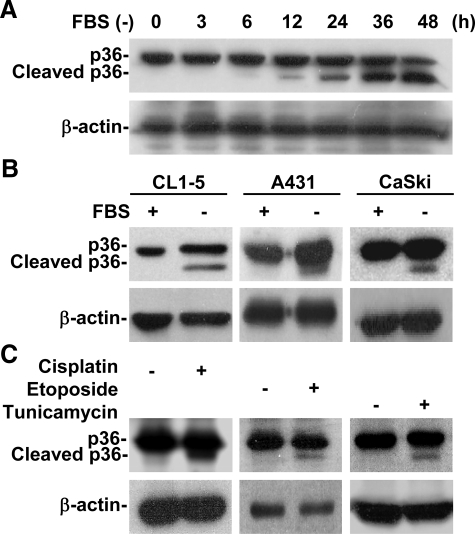

A549 cells were serum-deprived for various times. We found, using Western blotting, that serum withdrawal time-dependently caused annexin A2 (p36) (Figure 2A) and p11 (data not shown) cleavage, and, using RT-PCR, that the mRNA expression of neither annexin A2 nor p11 (data not shown) had decreased. The results were similar in CL1-5 human lung epithelial cells, A431 human epidermoid cells, and CaSki human epidermoid cervical carcinoma cells (Figure 2B). Additional results showed that the anticancer drugs cisplatin, etoposide, and tunicamycin also induced annexin A2 cleavage (Figure 2C), which indicated that apoptotic stimuli posttranscriptionally caused annexin A2 cleavage.

Figure 2.

Apoptotic stimuli caused annexin A2 cleavage. (A) A549 cells (5 × 105) were cultured under serum withdrawal for the indicated times. We used Western blotting to determine the protein expression of annexin A2 (p36). (B) CL1-5 human lung epithelial cells, A431 human epidermoid epithelial cells, and CaSki human epidermoid cervical carcinoma cells were cultured under serum withdrawal for 36 h. We used Western blotting to determine annexin A2 (p36) protein expression. (C) A549 cells (5 × 105 cells) were treated with cisplatin (50 μM), etoposide (100 μM), or tunicamycin (5 μg/ml) for 36 h. We used Western blotting to determine annexin A2 (p36) protein expression. β-actin was the internal control. Data shown are representative of three individual experiments.

GSK-3 Was Essential for Annexin A2 Cleavage with Apoptotic Stimuli

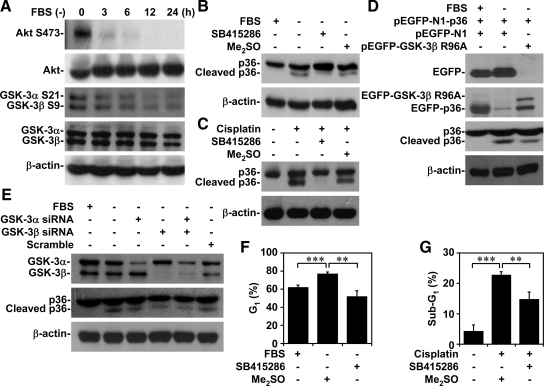

Growth factor withdrawal inactivates the PI3-kinase/Akt pathway and then activates GSK-3 (Maurer et al., 2006; Mishra et al., 2007). We used Western blotting to verify the involvement of PI3-kinase/Akt/GSK-3 signaling. Serum withdrawal time dependently caused Akt dephosphorylation at Ser473 (an inactivated form of Akt), GSK-3α dephosphorylation at Ser21 (an activated form of GSK-3α), and GSK-3β dephosphorylation at Ser9 (an activated form of GSK-3β) (Figure 3A). It also caused GSK-3β phosphorylation at Tyr216 (an activated form of GSK-3β) (data not shown).

Figure 3.

GSK-3 activation was essential for apoptotic stimuli-induced annexin A2 cleavage, cell cycle inhibition, and apoptosis. (A) A549 cells (5 × 105) were cultured under serum withdrawal for the indicated times. We used Western blotting to determine the protein expression of Akt (Ser473), GSK-3α (Ser21), and GSK-3β (Ser9). (B and C) A549 cells (5 × 105) were treated with or without GSK-3 inhibitor SB415286 (25 μM) and then cultured under serum withdrawal or normal culture conditions with cisplatin (50 μM) cotreatment for 36 h. We used Western blotting to determine the expression of annexin A2 (p36). Me2SO was used for the negative control. (D) A549 cells (2 × 105) were transfected with annexin A2 (pEGFP-N1-p36; 50 nM) and then cotransfected with or without control vector (pEGFP-N1; 50 nM) and GSK-3β dominant-negative mutant R96A (pEGFP-GSK-3β R96A; 50 nM) for 6 h and then cultured under serum withdrawal for 36 h. We used Western blotting to determine the expression of EGFP, GSK-3β, and annexin A2 (p36). (E) A549 cells (2 × 105) were transfected with or without GSK-3α, GSK-3β, or GSK-3α/β siRNA (50 nM) for 48 h and then cultured under serum withdrawal for 36 h. We used Western blotting to determine the expression of GSK-3α/β and annexin A2 (p36). Scrambled siRNA (50 nM) was used for the negative control. β-actin was the internal control. Data shown are representative of three individual experiments. (F and G) A549 cells (5 × 105) were treated with SB415286 (25 μM) and then cultured under serum withdrawal or under normal culture conditions with cisplatin (50 μM) cotreatment for 36 h. Cell cycles were determined using PI staining and then flow cytometry. Me2SO was used for the negative control. The percentages of cells in the G1 or subG1 phase are means ± SEM from three individual experiments with triplicate cultures. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

To investigate the role of GSK-3 in annexin A2 cleavage, we inhibited GSK-3 by using specific inhibitor SB415286, dominant-negative mutant, and siRNA. We found that SB415286 (Figure 3, B and C); GSK-3β dominant-negative mutant R96A (Figure 3D); and GSK-3α, GSK-3β, and GSK-3α/β siRNA (Figure 3E) decreased annexin A2 cleavage in A549 cells under serum withdrawal or cisplatin treatment. Furthermore, GSK-3β overexpression increased serum withdrawal-induced annexin A2 cleavage (data not shown). These results thus showed the dependence of apoptotic stimuli-induced annexin A2 cleavage on a GSK-3–regulated pathway.

Our data (Figure 1) and other studies (Chiang et al., 1999; Huang et al., 2008) indicated a regulatory role for annexin A2 in the cell cycle and for survival. We also found that GSK-3 affected annexin A2 cleavage under apoptotic stimuli. Our investigation of GSK-3 involvement in serum withdrawal-induced cell cycle inhibition and cisplatin-induced apoptosis showed that inhibiting GSK-3 with SB415286 significantly (p < 0.05) blocked serum withdrawal-induced cell cycle arrest in the G1 phase (Figure 3F) and cisplatin-induced apoptosis (Figure 3G). These results are evidence that GSK-3 activation is involved in serum withdrawal-induced cell cycle inhibition and cisplatin-induced apoptosis.

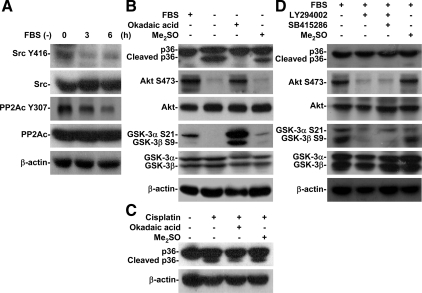

PP2A-triggered Akt Inactivation, Followed by GSK-3 Activation, and Contributed to Apoptotic Stimuli-induced Annexin A2 Cleavage

PP2A negatively regulates PI3-kinase/Akt and positively regulates GSK-3 (Lin et al., 2007). Tyrosine kinase Src generally inhibits PP2A by causing phosphorylation at Tyr307 (Chen et al., 1992, 1994). Using Western blotting, we found that serum withdrawal time-dependently induced dephosphorylation of Src (Tyr416) (an inactivated form of Src) and PP2Ac (Tyr307) (an activated form of PP2A) (Figure 4A). PP2A inhibitor OA blocked serum withdrawal-induced annexin A2 cleavage as well as dephosphorylation of Akt (Ser473), GSK-3α (Ser21), and GSK-3β (Ser9) (Figure 4B), which verified the essential involvement of PP2A in annexin A2 cleavage. Moreover, OA blocked cisplatin-induced annexin A2 cleavage (Figure 4C). Under normal growth conditions, Src inhibitor PP2 also induced Akt and GSK-3β dephosphorylation at Ser473 and Ser9, respectively, and caused GSK-3–regulated annexin A2 cleavage (Supplemental Figure S1). Together, these results confirmed that PP2A-triggered GSK-3 activation, induced by Akt inactivation, is involved in apoptotic stimuli-induced annexin A2 cleavage.

Figure 4.

PP2A-regulated GSK-3 activation was essential for apoptotic stimuli-induced annexin A2 cleavage. (A) A549 cells (5 × 105) were cultured under serum withdrawal for the indicated times. We used Western blotting to determine the protein expression of Src (Tyr416) and PP2Ac (Tyr307). (B and C) A549 cells (5 × 105) were treated with or without the PP2A inhibitor okadaic acid (100 nM) and then cultured under serum withdrawal or normal culture conditions with cisplatin (50 μM) cotreatment for 36 h. We used Western blotting to determine the expression of annexin A2 (p36). (D) A549 cells (5 × 105) were grown under normal conditions and treated with or without the PI3-kinase inhibitor LY294002 (50 μM) or SB415286 (25 μM) for 36 h. We used Western blotting to determine the protein expression of annexin A2 (p36), Akt (Ser473), GSK-3α (Ser21), and GSK-3β (Ser9). β-actin was the internal control. Me2SO was used for the negative control. Data shown are representative of three individual experiments.

PI3-Kinase/Akt Signaling Negatively Regulated GSK-3

To clarify the role of the PI3-kinase/Akt/GSK-3 pathway, we used PI3-kinase inhibitor LY294002 to inactivate Akt signaling. We found, by using Western blotting, that LY294002 was unable to cause annexin A2 cleavage under normal growth conditions (Figure 4D). However, under serum withdrawal, LY294002 increased annexin A2 cleavage (data not shown). We confirmed that LY294002 caused dephosphorylation of Akt (Ser473) and GSK-3β (Ser9) (Figure 4D). These results indicated that GSK-3 activation alone did not induce annexin A2 cleavage.

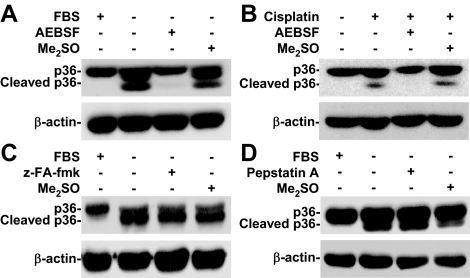

Serine Proteases but Not Cathepsins Were Involved in Apoptotic Stimuli-induced Annexin A2 Cleavage

Lysosomal proteases are involved in annexin A2 cleavage (Cuervo et al., 2000). To investigate the mechanism of annexin A2 cleavage, broad-spectrum serine protease inhibitor AEBSF, cathepsin B inhibitor z-FA-fmk, and cathepsin D inhibitor pepstatin A were used. Western blotting showed that neither z-FA-fmk (Figure 5C) nor pepstatin A (Figure 5D) blocked annexin A2 cleavage under serum withdrawal. Only AEBSF blocked serum withdrawal- (Figure 5A) and cisplatin (Figure 5B)-induced annexin A2 cleavage. These results mean that serine proteases, but not cathepsins, are essential for apoptotic stimuli-induced annexin A2 cleavage.

Figure 5.

Serine proteases, not cathepsins, caused apoptotic stimuli-induced annexin A2 cleavage. (A and B) A549 cells (5 × 105) were treated with or without serine protease inhibitor AEBSF (50 μM) and then cultured under serum withdrawal or normal culture conditions with cisplatin (50 μM) cotreatment for 36 h. We used Western blotting to determine the expression of annexin A2 (p36). (C and D) A549 cells (5 × 105) were treated with or without the cathepsin B/L inhibitor z-FA-fmk (50 μM) or the cathepsin D inhibitor pepstatin A (5 μg/ml) and then cultured under serum withdrawal for 36 h. We used Western blotting to determine the expression of annexin A2 (p36). β-actin was the internal control. Me2SO was used for the negative control. Data shown are representative of three individual experiments.

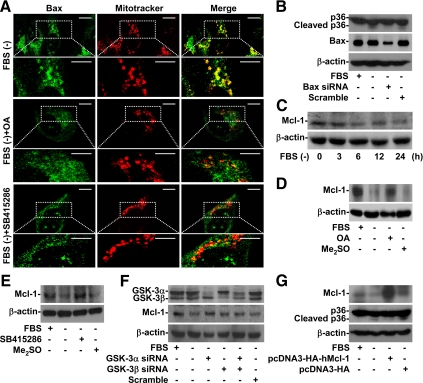

Bax Activation and Mcl-1 Degradation Were Involved in Serum Withdrawal-induced Annexin A2 Cleavage

Growth factor withdrawal may cause GSK-3–induced Bax activation and Mcl-1 degradation and then cause mitochondrial membrane permeabilization (Linseman et al., 2004; Maurer et al., 2006). Mcl-1 is a pivotal antiapoptotic that inhibits Bax activation before mitochondrial injury (Germain et al., 2008). PP2A dephosphorylates Bax at serine 184 and increases its proapoptotic effect in mitochondria by regulating protein conformational change (Chen et al., 1992). Using rhodamine 123 and then flow cytometry, we found that serum withdrawal time-dependently caused the loss of ΔΨm in A549 cells (Supplemental Figure S2). We used immunostaining and then confocal microscopy for an additional investigation of Bax and Mcl-1 involvement. We found that Bax was relocated from the cytosol to mitochondria in the serum-withdrawal group (Figure 6A, top) but not in the untreated group (data not shown). We then showed that OA (Figure 6A, middle) and SB415286 (Figure 6A, bottom) blocked serum withdrawal-induced Bax relocation from the cytosol to mitochondria. We next silenced Bax expression with siRNA. Bax knockdown cells were resistant to serum withdrawal-induced annexin A2 cleavage (Figure 6B). Furthermore, Western blot analysis showed that Mcl-1 was time-dependently degraded under serum withdrawal (Figure 6C). Using Western blotting, we found that OA (Figure 6D) and SB415286 (Figure 6E) blocked serum withdrawal-induced Mcl-1 degradation, which confirmed that PP2A and GSK-3 were involved in Mcl-1 degradation. Furthermore, treating cells with GSK-3 siRNA decreased Mcl-1 degradation (Figure 6F). These results confirmed the importance of PP2A and GSK-3 in Bax and Mcl-1 regulation. We also found that Mcl-1 overexpression prevented annexin A2 cleavage (Figure 6G), which showed the involvement of mitochondrial injury, including Bax activation and Mcl-1 degradation, in serum withdrawal-induced annexin A2 cleavage.

Figure 6.

PP2A- and GSK-3–regulated Bax activation and Mcl-1 destabilization were essential for serum withdrawal-induced annexin A2 cleavage. (A) A549 cells (3 × 104) were treated with or without OA (100 nM) or SB415286 (25 μM) and then cultured under serum withdrawal for 24 h. We used immunostaining and then confocal microscopy to determine Bax (Bax; green) expression. MitoTracker Red CMXRos (Mitotracker; red) was used for mitochondria counterstaining. The colocalization is also shown (Merge; yellow). Bar, 8 μm. (B) A549 cells (2 × 105) were transfected with or without Bax siRNA (50 nM) for 48 h and then cultured under serum withdrawal for 36 h. We used Western blotting to determine the expression of Bax and annexin A2 (p36). Scrambled siRNA (50 nM) was used for the negative control. (C) A549 cells (5 × 105) were cultured under serum withdrawal for the indicated times. We used Western blotting to determine Mcl-1 expression. (D–F) A549 cells (5 × 105) were treated with or without OA (100 nM), SB415286 (25 μM), or GSK-3α/β siRNA (50 nM) for 48 h and then cultured under serum withdrawal for 36 h. We used Western blotting to determine the expression of Mcl-1. Me2SO and scrambled siRNA were used for the negative controls. (G) A549 cells (2 × 105) were transfected with or without control vector (pcDNA3-HA; 50 nM) and human Mcl-1 (pcDNA3-HA-hMcl-1; 50 nM) for 6 h and then cultured under serum withdrawal for 36 h. We used Western blotting to determine the expression of Mcl-1 and annexin A2 (p36). β-actin was the internal control. Data shown are representative of three individual experiments.

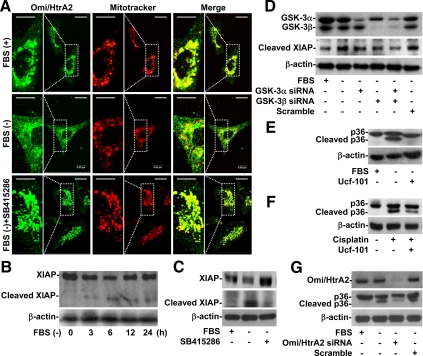

Mitochondrial Serine Protease Omi/HtrA2 Was Involved in Apoptotic Stimuli-induced Annexin A2 Cleavage

After the mitochondrial membrane is permeabilized, Omi/HtrA2, a mitochondrial serine protease, is released into the cytoplasm. This leads to the cleavage of inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs), the activation of caspases, and then apoptosis (Yang et al., 2003). Furthermore, Mcl-1 negatively regulates Omi/HtrA2 relocation (Han et al., 2006), whereas Bax positively regulates it (Yamaguchi et al., 2003). Immunostaining and confocal microscopy showed that Omi/HtrA2 was located primarily in the mitochondria (punctate form) (Figure 7A, top). We also found that Omi/HtrA2 relocated from mitochondria to the cytosol (diffuse form) in cells under serum withdrawal (Figure 7A, middle). Notably, SB415286 blocked this relocation (Figure 7A, bottom). To evaluate the cytosolic activity of Omi/HtrA2, we used Western blotting to analyze the expression of XIAP, a substrate of Omi/HtrA2. We first found that XIAP was time-dependently cleaved under serum withdrawal (Figure 7B). Inhibiting GSK-3 with SB415286 blocked Omi/HtrA2-mediated XIAP cleavage (Figure 7C). Furthermore, XIAP cleavage decreased in GSK-3 knockdown cells (Figure 7D). To verify whether Omi/HtrA2 is involved in annexin A2 cleavage, Ucf-101, a specific Omi/HtrA2 inhibitor, and siRNA were used. We found that Ucf-101 (Figure 7, E and F) and Omi/HtrA2 siRNA (Figure 7G) decreased the cleavage of annexin A2 under both serum withdrawal and cisplatin treatment. These results strongly indicated that Omi/HtrA2 is released from mitochondria to the cytosol and is required for annexin A2 cleavage under apoptotic stimuli.

Figure 7.

GSK-3–regulated activation of mitochondrial serine protease Omi/HtrA2 was essential for apoptotic stimuli-induced annexin A2 cleavage. (A) A549 cells (3 × 104) were treated with or without SB415286 (25 μM) and then cultured under serum withdrawal for 24 h. We used immunostaining and then confocal microscopy to determine the expression of Omi/HtrA2 (Omi/HtrA2; green). MitoTracker Red CMXRos (Mitotracker; red) was used to counterstain mitochondria. The colocalization is also shown (Merge; yellow). Bar, 8 μm. (B) A549 cells (5 × 105) were cultured under serum withdrawal for the indicated times. We used Western blotting to determine the expression of XIAP to evaluate Omi/HtrA2 activation. (C and D) A549 cells (5 × 105) were treated with or without SB415286 (25 μM) or GSK-3α/β siRNA (50 nM) for 48 h and then cultured under serum withdrawal for 36 h. We used Western blotting to determine the expression of XIAP. Scrambled siRNA (50 nM) was used for the negative control. (E and F) A549 cells (5 × 105) were treated with or without the Omi/HtrA2 inhibitor ucf-101 (25 μM) and then cultured under serum withdrawal or normal culture conditions with cisplatin (50 μM) cotreatment for 36 h. We used Western blotting to determine the expression of annexin A2 (p36). (G) A549 cells (2 × 105) were transfected with or without Omi/HtrA2 siRNA (50 nM) for 48 h and then cultured under serum withdrawal for 36 h. We used Western blotting to determine the expression of Omi/HtrA2 and annexin A2 (p36). β-actin was the internal control. Data shown are representative of three individual experiments.

DISCUSSION

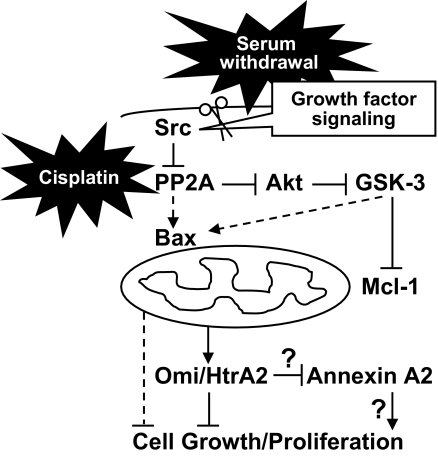

In the present study, we have provided the first evidence showing the mechanisms of annexin A2 cleavage via a PP2A/Akt/GSK-3/Mcl-1/Bax/Omi/HtrA2–regulating pathway in cells under apoptotic stimuli. We also verified the physiological effects of annexin A2 destabilization on cell cycle inhibition and apoptosis (for a schematic model, see Figure 8). Although either serum withdrawal or cisplatin caused annexin A2 cleavage, the cleavage site remains unclear. To determine the location of that site, we transfected cells with an annexin A2 plasmid coencoded EGFP fused to the C terminus of annexin A2. Because Western blot analysis using EGFP antibodies showed that the cleaved annexin A2 contained EGFP, we hypothesized that the N terminus of annexin A2 was the cleaved fragment of annexin A2. More investigation is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Figure 8.

Schematic model for apoptotic stimuli-induced annexin A2 cleavage. Under normal growth conditions, Akt constitutively phosphorylates GSK-3 and inactivates it. Under serum withdrawal or cisplatin treatment, inactivated Src and activated PP2A inactivate Akt and activate GSK-3. PP2A and GSK-3 regulate Bax activation and Mcl-1 destabilization. After the mitochondrial membrane has been permeabilized, serine protease Omi/HtrA2 is relocated to the cytosol, where it causes annexin A2 cleavage and then cell cycle inhibition and apoptosis.

During nutrient deprivation, annexin A2 is, as with many aggregative and unfolded intracellular proteins, degraded within lysosomes via an autophagy-mediated pathway (Cuervo et al., 2000). In the present study, we found evidence that serum withdrawal causes annexin A2 cleavage in A549 and CL1-5 human lung epithelial cells and A431 and CaSki human epidermoid cells. We also showed that annexin A2 down-regulation is independent of transcriptional repression but dependent upon posttranscriptional mechanisms. Inconsistent with previous studies (Cuervo et al., 2000), however, we also showed that lysosomal cathepsin B and cathepsin D did not cause annexin A2 cleavage.

In our search for the unidentified molecular mechanism of annexin A2 cleavage, in the present study, we investigated the involvement of signaling pathways that are activated and inactivated by apoptotic stimuli. Annexin A2 is degraded in murine IL-3–dependent FL5.12 and Baf-3 proB lymphoid cells when they are cultured under IL-3 withdrawal (Matsunaga et al., 2004). The stability of annexin A2 is positively regulated by the IL-3–initiated PI3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway. In IL-3 withdrawal-treated FL-5.12 cells, after PI3-kinase and Akt have been inactivated. Mcl-1 is phosphorylated by GSK-3 and then is degraded through the ubiquitinylation-proteasome system (Maurer et al., 2006). Generally, down-regulation of Mcl-1 causes mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and apoptosis. Here, we first showed that serum withdrawal-induced annexin A2 cleavage is also GSK-3 dependent. We also showed the novel effect of Src/PP2A/Akt/GSK-3/Mcl-1 signaling for annexin A2 cleavage. Under normal growth conditions, inhibiting PI3-kinase/Akt signaling by using LY294002 did not induce annexin A2 cleavage, whereas GSK-3 was activated, further supporting the potent role of PP2A. However, the role of PP2A needs to be further studied.

After GSK-3 has been activated, Mcl-1 is degraded under IL-3 withdrawal and proteasomes are important for the intracellular removal of Mcl-1 (Maurer et al., 2006). However, we found a proteasome-independent annexin A2 cleavage because MG132, a proteasome inhibitor, did not block annexin A2 cleavage (data not shown). Notably, we also showed that instead of proteasomes, mitochondrial serine protease Omi/HtrA2 blocked annexin A2 cleavage. In general, Omi/HtrA2 is proapoptotic because it degrades IAPs (Yang et al., 2003; Saelens et al., 2004). After the mitochondrial membrane has been permeabilized, Omi/HtrA2 is relocated from the mitochondria to the cytosol. Bcl-2 family proteins control the release of Omi/HtrA2. Bax, Bim, and Bid induce its release, but Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and Mcl-1 inhibit it (Kuwana and Newmeyer, 2003; Han et al., 2006). Thus, regulating Bcl-2 family proteins may be important for controlling annexin A2 cleavage.

The present study further showed that PP2A and GSK-3 are essential for Bax translocation to mitochondria, for Mcl-1 destabilization, and for Omi/HtrA2 relocation from the mitochondria to the cytosol. Mcl-1 negatively and indirectly regulates Bax in mitochondria (Germain et al., 2008). Furthermore, PP2A regulates GSK-3 (Lin et al., 2007), whereas both PP2A and GSK-3 enhance the proapoptotic function of Bax and down-regulate Mcl-1 through a posttranscriptional mechanism (Linseman et al., 2004; Maurer et al., 2006; Xin and Deng, 2006). We therefore hypothesize that PP2A/Bax/Mcl-1 signaling is central for controlling GSK-3–mediated annexin A2 cleavage.

The potential effects of annexin A2 cleavage remain largely unknown, especially on heterotetramer stability and cellular regulation. However, it has been hypothesized (Johnsson et al., 1988; Gerke et al., 2005) that cleaved annexin A2 loses its ability to bind with p11 because the N terminus, which contains the p11 binding sites, is lost when annexin A2 is cleaved. Further studies are needed to clarify this hypothesis.

The physiological functions of annexin A2 are diverse: phagocytosis, lipid raft formation and cytoskeleton reorganization, exocytosis, endocytosis, cell division and proliferation, apoptosis, and cancer cell migration and metastasis (Sarafian et al., 1991; Emans et al., 1993; Chiang et al., 1999; Menell et al., 1999; Oliferenko et al., 1999; Babiychuk and Draeger, 2000; Babiychuk et al., 2002; Fan et al., 2004; Singh et al., 2004; Morel and Gruenberg, 2007; Huang et al., 2008). In the present study, we showed that annexin A2 regulates the cell cycle and survival. Under apoptotic stimuli, GSK-3–regulated annexin A2 destabilization may contribute to serum-withdrawal-induced cell cycle inhibition and cisplatin-induced apoptosis. However, the mechanisms are unknown. Because annexin A2 is involved in membrane organization and dynamics, cleaving annexin A2 may prevent it from performing its structural functions and signal transduction (Oliferenko et al., 1999; Babiychuk and Draeger, 2000; Babiychuk et al., 2002; Singh et al., 2004). Annexin A2 knockdown inhibits cell proliferation (Chiang et al., 1999). Interestingly, annexin A2 is identified for the activation of protein kinase 3-phosphoglycerate kinase, an important regulator of DNA synthesis (Kumble and Vishwanatha, 1991). It is hypothesized that annexin A2 cleavage loses abilities to promote cell cycle progression. The targets and the effects of cleaved and uncleaved annexin A2 need further investigation.

In conclusion, we showed that PP2A-regulated GSK-3 and mitochondrial Omi/HtrA2 are indispensable for cleaving annexin A2 under serum withdrawal and cisplatin treatment. Annexin A2 is overexpressed in several kinds of metastatic tumors (Roseman et al., 1994; Menell et al., 1999; Emoto et al., 2001; Sharma et al., 2006; Esposito et al., 2006). We hypothesize that interference on the GSK-3/Omi/HtrA2 pathway contributes to oncogenesis resulting from annexin A2 overexpression. More investigation is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. R. Anderson for critical reading of this manuscript and Bill Franke for editorial assistance. This work was supported by National Science Council, Taiwan, grant 96-2320-B-006-018-MY3 and the Landmark Project C020 of National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan.

Abbreviations used:

- GSK

glycogen synthase kinase

- PP

protein phosphatase

- siRNA

small interfering RNA.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E09-02-0174) on August 5, 2009.

REFERENCES

- Babiychuk E. B., Draeger A. Annexins in cell membrane dynamics. Ca(2+)-regulated association of lipid microdomains. J. Cell Biol. 2000;150:1113–1124. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.5.1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babiychuk E. B., Monastyrskaya K., Burkhard F. C., Wray S., Draeger A. Modulating signaling events in smooth muscle: cleavage of annexin 2 abolishes its binding to lipid rafts. FASEB J. 2002;16:1177–1184. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0070com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Martin B. L., Brautigan D. L. Regulation of protein serine-threonine phosphatase type-2A by tyrosine phosphorylation. Science. 1992;257:1261–1264. doi: 10.1126/science.1325671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Parsons S., Brautigan D. L. Tyrosine phosphorylation of protein phosphatase 2A in response to growth stimulation and v-src transformation of fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:7957–7962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang Y., Rizzino A., Sibenaller Z. A., Wold M. S., Vishwanatha J. K. Specific down-regulation of annexin II expression in human cells interferes with cell proliferation. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1999;199:139–147. doi: 10.1023/a:1006942128672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross D. A., Alessi D. R., Cohen P., Andjelkovich M., Hemmings B. A. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B. Nature. 1995;378:785–789. doi: 10.1038/378785a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo A. M., Gomes A. V., Barnes J. A., Dice J. F. Selective degradation of annexins by chaperone-mediated autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:33329–33335. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005655200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deora A. B., Kreitzer G., Jacovina A. T., Hajjar K. A. An annexin 2 phosphorylation switch mediates p11-dependent translocation of annexin 2 to the cell surface. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:43411–43418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408078200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emans N., Gorvel J. P., Walter C., Gerke V., Kellner R., Griffiths G., Gruenberg J. Annexin II is a major component of fusogenic endosomal vesicles. J. Cell Biol. 1993;120:1357–1369. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.6.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emoto K., et al. Annexin II overexpression is correlated with poor prognosis in human gastric carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:1339–1345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito I., et al. Tenascin C and annexin II expression in the process of pancreatic carcinogenesis. J. Pathol. 2006;208:673–685. doi: 10.1002/path.1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan X., Krahling S., Smith D., Williamson P., Schlegel R. A. Macrophage surface expression of annexins I and II in the phagocytosis of apoptotic lymphocytes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:2863–2872. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-09-0670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerke V., Creutz C. E., Moss S. E. Annexins: linking Ca2+ signalling to membrane dynamics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:449–461. doi: 10.1038/nrm1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerke V., Moss S. E. Annexins: from structure to function. Physiol. Rev. 2002;82:331–371. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain M., Milburn J., Duronio V. MCL-1 inhibits BAX in the absence of MCL-1/BAX Interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:6384–6392. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould K. L., Woodgett J. R., Isacke C. M., Hunter T. The protein-tyrosine kinase substrate p36 is also a substrate for protein kinase C in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1986;6:2738–2744. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.7.2738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajjar K. A., Jacovina A. T., Chacko J. An endothelial cell receptor for plasminogen/tissue plasminogen activator. I. Identity with annexin II. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:21191–21197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajjar K. A., Krishnan S. Annexin II: a mediator of the plasmin/plasminogen activator system. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 1999;9:128–138. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(99)00020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J., Goldstein L. A., Gastman B. R., Rabinowich H. Interrelated roles for Mcl-1 and BIM in regulation of TRAIL-mediated mitochondrial apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:10153–10163. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510349200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Jin Y., Yan C. H., Yu Y., Bai J., Chen F., Zhao Y. Z., Fu S. B. Involvement of Annexin A2 in p53 induced apoptosis in lung cancer. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2008;309:117–123. doi: 10.1007/s11010-007-9649-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsson N., Marriott G., Weber K. p36, the major cytoplasmic substrate of src tyrosine protein kinase, binds to its p11 regulatory subunit via a short amino-terminal amphiphatic helix. EMBO J. 1988;7:2435–2442. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassam G., Manro A., Braat C. E., Louie P., Fitzpatrick S. L., Waisman D. M. Characterization of the heparin binding properties of annexin II tetramer. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:15093–15100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.24.15093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumble K. D., Vishwanatha J. K. Immunoelectron microscopic analysis of the intracellular distribution of primer recognition proteins, annexin 2 and phosphoglycerate kinase, in normal and transformed cells. J. Cell Sci. 1991;99:751–758. doi: 10.1242/jcs.99.4.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwana T., Newmeyer D. D. Bcl-2-family proteins and the role of mitochondria in apoptosis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2003;15:691–699. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C. F., Chen C. L., Chiang C. W., Jan M. S., Huang W. C., Lin Y. S. GSK-3beta acts downstream of PP2A and the PI 3-kinase-Akt pathway, and upstream of caspase-2 in ceramide-induced mitochondrial apoptosis. J. Cell Sci. 2007;120:2935–2943. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linseman D. A., Butts B. D., Precht T. A., Phelps R. A., Le S. S., Laessig T. A., Bouchard R. J., Florez-McClure M. L., Heidenreich K. A. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta phosphorylates Bax and promotes its mitochondrial localization during neuronal apoptosis. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:9993–10002. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2057-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga T., et al. Regulation of annexin II by cytokine-initiated signaling pathways and E2A-HLF oncoprotein. Blood. 2004;103:3185–3191. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer U., Charvet C., Wagman A. S., Dejardin E., Green D. R. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 regulates mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and apoptosis by destabilization of MCL-1. Mol. Cell. 2006;21:749–760. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menell J. S., Cesarman G. M., Jacovina A. T., McLaughlin M. A., Lev E. A., Hajjar K. A. Annexin II and bleeding in acute promyelocytic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;340:994–1004. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904013401303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra R., Barthwal M. K., Sondarva G., Rana B., Wong L., Chatterjee M., Woodgett J. R., Rana A. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta induces neuronal cell death via direct phosphorylation of mixed lineage kinase 3. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:30393–30405. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705895200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morel E., Gruenberg J. The p11/S100A10 light chain of annexin A2 is dispensable for annexin A2 association to endosomes and functions in endosomal transport. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e1118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliferenko S., Paiha K., Harder T., Gerke V., Schwarzler C., Schwarz H., Beug H., Gunthert U., Huber L. A. Analysis of CD44-containing lipid rafts: recruitment of annexin II and stabilization by the actin cytoskeleton. J. Cell Biol. 1999;146:843–854. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.4.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roseman B. J., Bollen A., Hsu J., Lamborn K., Israel M. A. Annexin II marks astrocytic brain tumors of high histologic grade. Oncol. Res. 1994;6:561–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saelens X., Festjens N., Vande Walle L., van Gurp M., van Loo G., Vandenabeele P. Toxic proteins released from mitochondria in cell death. Oncogene. 2004;23:2861–2874. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarafian T., Pradel L. A., Henry J. P., Aunis D., Bader M. F. The participation of annexin II (calpactin I) in calcium-evoked exocytosis requires protein kinase C. J. Cell Biol. 1991;114:1135–1147. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.6.1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M. R., Koltowski L., Ownbey R. T., Tuszynski G. P., Sharma M. C. Angiogenesis-associated protein annexin II in breast cancer: selective expression in invasive breast cancer and contribution to tumor invasion and progression. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2006;81:146–156. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh T. K., Abonyo B., Narasaraju T. A., Liu L. Reorganization of cytoskeleton during surfactant secretion in lung type II cells: a role of annexin II. Cell. Signal. 2004;16:63–70. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(03)00089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin M., Deng X. Protein phosphatase 2A enhances the proapoptotic function of Bax through dephosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:18859–18867. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512543200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi H., Bhalla K., Wang H. G. Bax plays a pivotal role in thapsigargin-induced apoptosis of human colon cancer HCT116 cells by controlling Smac/Diablo and Omi/HtrA2 release from mitochondria. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1483–1489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q. H., Church-Hajduk R., Ren J., Newton M. L., Du C. Omi/HtrA2 catalytic cleavage of inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) irreversibly inactivates IAPs and facilitates caspase activity in apoptosis. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1487–1496. doi: 10.1101/gad.1097903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh H. H., Lai W. W., Chen H. H., Liu H. S., Su W. C. Autocrine IL-6-induced Stat3 activation contributes to the pathogenesis of lung adenocarcinoma and malignant pleural effusion. Oncogene. 2006;25:4300–4309. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.