Abstract

Aim

The absence or ‘missingness’ of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) assay values because of genotype or related factors of interest may bias association and other studies. Missingness was determined for the Type 1 Diabetes Genetics Consortium (T1DGC) Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) data and was found to vary across the region, ranging up to 11.1% of the non-null proband SNPs, with a median of 0.3%. We consider factors related to missingness in the T1DGC data and briefly assess its possible influence on association studies.

Methods

We assessed associations of missingness in the SNP assay data with human leucocyte antigen (HLA) genotype of the individual and with SNP genotypes of the parents. Within-cohort analyses were combined (over all cohorts) using (i) Mantel–Haenszel tests for two-by-two tables or (ii) by combining test statistics for larger tables and regression models. Mixed effect regression models were used to assess association of the SNP genotypes with affected status of the offspring after adjustment for parental SNP genotypes, cohort membership and HLA genotypes. Log-linear models were used to assess association of missingness in the unaffected sib assays with SNP genotypes of the probands.

Results

Missingness of SNP values near the HLA class I (A, B and C) and class II (DR, DQ and DP) loci is strongly associated with carriage of corresponding HLA genotypes within these groups. Similar associations pertain to missing values among the microsatellite data. In at least some of these cases, regions of missingness coincided with known deletion regions corresponding to the associated HLA haplotype. We conjecture that other regions of associated missingness may point to similar haplotypic deletions. Analysis of association patterns of SNP genotypes with affected status of offspring does not indicate strong informative missingness. However, association of missingness in proband data with parental SNP genotypes may impact transmission disequilibrium test (TDT)-type analyses. Comparisons of affected and unaffected siblings point to possible susceptibility regions additional to the classical HLA-DR3/4 alleles near BAT4-LY6G5B-BAT5 and NOTCH4.

Conclusions

Potentially informative missingness in SNP assay values in the MHC region may impact on association and related analyses based on the T1DGC data. These results suggest that it would be prudent to assess the degree to which missingness may abrogate assessed SNP disease markers in such studies. Initial analyses based on comparison of affected and unaffected status in offspring suggest that at least these may be little affected.

Keywords: association studies, deletions, HLA, informative missingness, MHC fine mapping, type 1 diabetes

Introduction

While non-informative or random missingness can cause loss of information and hence reduced power in statistical analyses, data missing non-randomly or because of factors related to those under study may also bias results [1]. This is particularly true if the data are missing as a result of genotype. The Type 1 Diabetes Genetics Consortium (T1DGC) Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) fine-mapping single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) assays are subject to varying degrees of missingness, some being unavailable for whole cohorts while others are present only for subsets of individuals, even within the same family.

In the process of performing association studies, we noted unusual patterns of missingness for some SNPs. We subsequently carried out a more comprehensive analysis of the missing SNP assays in the T1DGC database. Here, we show that assay missingness is associated with human leucocyte antigen (HLA) genotypes for different SNPs across the MHC region.

Our analyses typically concentrate on the proband or first-listed affected offspring but apply also to other offspring and to parents. We consider whether SNP missingness is associated with affected status, and also consider associations of proband SNP missingness with parental SNP genotypes. Analyses suggest that comparisons between affected and unaffected sibs, when appropriately conditioned, are not strongly affected by SNP missingness, indicating that such analyses may not be biased by these omissions. We provide a brief comparison along these lines based on mixed effects regression of the number of major SNP alleles, which points to possible markers near BAT4-LY6G5B-BAT5 and NOTCH4 independent of the well-known strong HLA-DRB1*03/04/15 effects and possible haplotypic markers near HLA-DQB2 and between HLA-DQB1 and HLA-DQA2.

Materials and Methods

For simplicity, we consider only two-digit HLA genotypes (HLA-A, B, C, DRB1, DQA1, DQB1, DPA1 and DPB1) in the analyses reported here, and restrict to individuals for whom not all SNP assays are missing. Associations of SNP missingness and HLA genotypes or missingness in proband SNPs related to parental SNP genotypes were analysed within cohorts and combined over cohorts using Mantel–Haenszel tests where the sub-tables were 2 × 2, or analysed using likelihood ratio tests within cohorts and combined over cohorts otherwise.

Probands were taken to be those identified as such in the T1DGC database, or the first-listed affected offspring in families where no proband was identified. For HLA associations, we included only those individuals classified as NIH race code 5 (White or Caucasian) to help avoid possible confounding because of effects of population substructure as a result of ethnic differences. For analysis purposes, SNP genotypes were coded as the number of major alleles as defined in the T1DGC. Comparisons of affected and unaffected sibs were based on McNemar tests (unadjusted) and using mixed effects modelling of the number of major SNP alleles. This latter approach accommodated within-family correlations.

The models for each SNP included adjustment forHLA-DRB1* 03/04 genotype combinations, HLA-DRB1*15 genotype, and ‘cohort membership’ as main effects. Analyses were carried out within the three informative parental groups that allow the same range in offspring major allele numbers. Test statistics were combined over these groups. While the ‘discreteness’ of allele number is at variance with the usual normality assumptions, for large samples, these models are robust to this violation of assumptions. All analyses were carried out in SPLUS 7.0 (Insightful, Seattle, WA, USA).

Results

Missingness of SNP Assay Data is Associated with HLA Genotypes

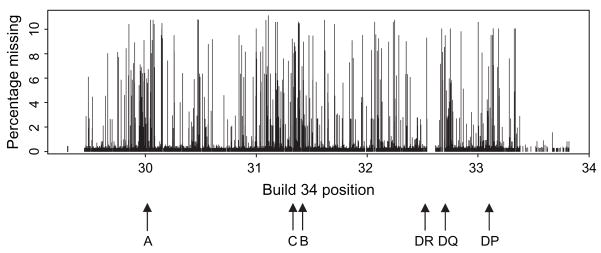

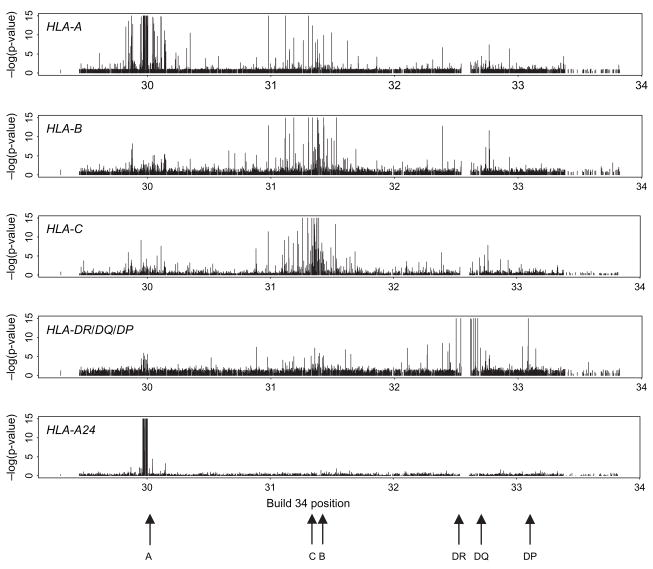

Overall percentages of missing SNP values for probands are plotted against Build 34 reference coordinates in figure 1, restricted to only those cohorts in which genotyping was performed. Missing values span the MHC region, with some clustering telomeric of HLA-A, around the HLA-B/C regions and again near the HLA-DR/DQ/DP regions. Minus log10 p values based on Mantel–Haenszel tests for association of SNP missingness with HLA genotype in the probands are illustrated in figure 2, where minimum p values at each SNP over the HLA-A, -B, -C and -DR/DQ/DP genotypes are shown along with the values specific to carriage of HLA-A24.

Fig. 1.

Percentages of missing single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) assay values for probands plotted against NCBI Build 34 coordinates for the T1DGC genotyped SNPs. Approximate positions of human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-A, -B, -C, -DP, -DQ and -DRB1 are indicated. Percentages are based only on cohorts for which typing of the SNP was carried out.

Fig. 2.

Missingness in proband single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) assay values associated with proband human leucocyte antigen (HLA) genotype. Associations were assessed for carriage of each two-digit HLA genotype. The plots show minus log10 p values by Build 34 coordinates aggregated over the HLA-A, -B, -C and -DR/DQ/DP subgroups and for HLA-A24. Aggregated plots show the smallest p values at each SNP for the genotypes in the subgroups. P values are truncated at 10−15.

To avoid the possibility of artefacts arising from small numbers in these analyses, we restricted to situations where at least 20 probands carried the HLA genotype and at least 20 SNP values were missing; however, similar results were obtained if this restriction was lifted. Strong associations between SNP missingness and HLA genotypes are found adjacent to the corresponding HLA regions. Similar association patterns were found for the parents, for the second affected offspring and for the (as yet) unaffected offspring (data not shown). In particular, a strong block is associated with carriage of HLA-A24 across the approximately 40 kb region telomeric of HLA-A, spanning Build 34 coordinates 29 966 243 to 30 004 716 bp (figure 2). This region contains 10 SNPs whose missingness is associated strongly (p < 10−15) with carriage of HLA-A24.

We then considered all individuals (parents and offspring) in the T1DGC data set who were not devoid of all SNP assays. At six of the abovementioned 10 SNPs, all 79 of these individuals who were homozygous for HLA-A24 had missing SNP values. At the other four SNPs, only two to nine HLA-A24 homozygous individuals (2.5–11.4%) had non-missing assays. This compares with an average 91.5% of non-missing assays for homozygous HLA-A24 individuals over all SNPs. These 10 SNPs are in strong LD and also share the property that very few individuals with heterozygous SNP alleles carried the HLA-A24 allele (median 0.28%, range 0–2.1%). By comparison, of those homozygous for the minor SNP allele, a median 44.4% (range 30.1–50.0%) carried HLA-A24, while of those homozygous for the major SNP allele a median 22.7% (range 19.7–27.8%) carried HLA-A24. These results are consistent with the identification in this region of an approximately 50 kb deletion block associated with HLA-A24 [2] and the tendency for such SNPs to be called as homozygous for the present allele [3].

Regions in which insertions/deletions (in/dels) and polymorphisms cluster also approximately coincide with the regions of association between HLA genotype and SNP missingness noted here [3–9]. A review of the potential impact of copy number variation on genomewide association studies can be found in Estivill and Armengol [4], while Gaudieri et al. [10] provide a summary of content in some of the insertions/deletions in the MHC class I region, including gene fragments of the multicopy HLA, MHC Class I Chain Related (MIC) and P5 genes.

Plots for each of the two-digit HLA types that showed evidence of association in probands are given in figure S1. While we do not carry out a comprehensive analysis of these in the present paper, we speculate that at least some of them may also be related to clustering of SNPs and deletions related to different HLA genotypes.

Missingness in Proband SNP Assay Data is Associated with Parental SNP Genotype

We considered association between missingness in the proband SNPs and the SNP genotypes of the corresponding parents. Associations were assessed by Mantel–Haenszel tests over cohorts for carriage of the major allele and/or homozygosity in the parents. Plots of the p values for association of missingness of the proband SNP with carriage of the major allele by the mother are shown in figure 3a. There was again concentration of associations in the same region telomeric of HLA-A and near the HLA-B/C and -DR/DQ/DP regions. Many of the more significant associations coincide with or are adjacent to those related to HLA missingness associations in figure 2. Similar results were obtained for the proband father (data not shown). Consequently, while further detailed assessment is needed, the association between proband SNP missingness and parental SNP genotype appears likely because of association of HLA and SNP genotypes and the attendant deletion-driven missingness attached to the former.

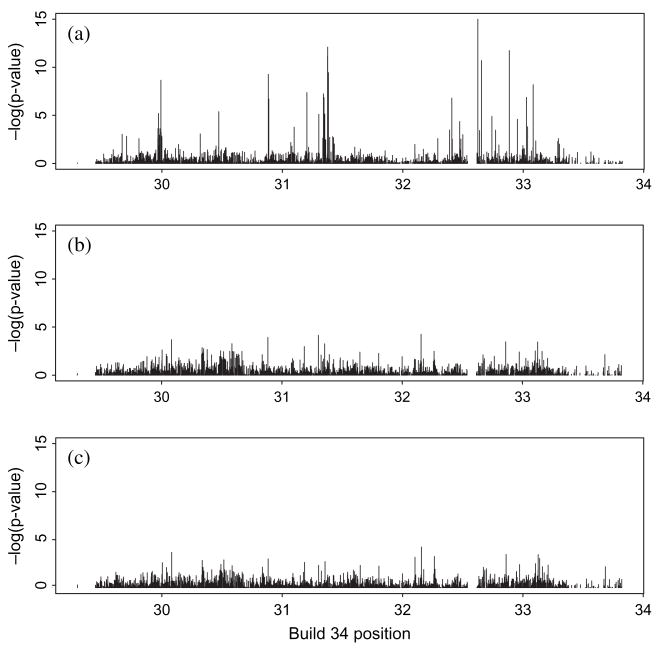

Fig. 3.

Missingness in the proband single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) is associated with SNP genotype of the parents. Plots show minus log10 p values for association of missing status of the proband SNP vs. maternal SNP genotype based on Mantel–Haenszel tests combining over cohorts. P values are truncated at 10−15. (a) Proband SNP missingness associated with maternal carriage of the major allele. (b) Proband SNP missingness associated with maternal homozygosity. (c) Proband SNP missingness associated with maternal heterozygosity among carriers of the major allele. Most association is with maternal minor allele homozygosity.

While overall proband SNP missingness was associated with carriage of the major allele by the mother, there was less evidence of overall maternal homozygosity being associated with proband SNP missingness (figure 3b) or of maternal homozygosity in analyses restricted to carriers of the major allele (figure 3c).

Comparison of SNP Genotypes in Affected and Non-affected Offspring

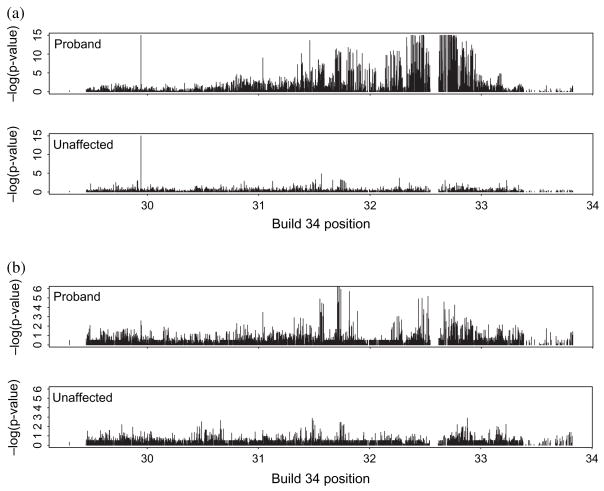

While a comprehensive analysis of markers is not the main purpose of this paper, we compared SNP genotypes for affected and unaffected sibs in the 717 families for whom the proband and first unaffected offspring had the same parents. Figure 4a displays minus log10 p values comparing unadjusted observed and expected SNP genotype frequencies given informative parental genotypes. Proband SNPs show clearly more significant deviations from expected over a large part of the MHC, particularly near the HLA-DR/DQ/DP region. Both show an artefactual association near position 29.94 Mb resulting from an imbalance in heterozygous genotypes. When restricted to cases where one parent is homozygous for the minor allele, the strong HLA-DR/DQ/DP effect is diminished, suggesting possible additional associations particularly near MICB and BAT2/3/4 (figure 4b). Some of these again coincide with regions of missingness and may thus be influenced.

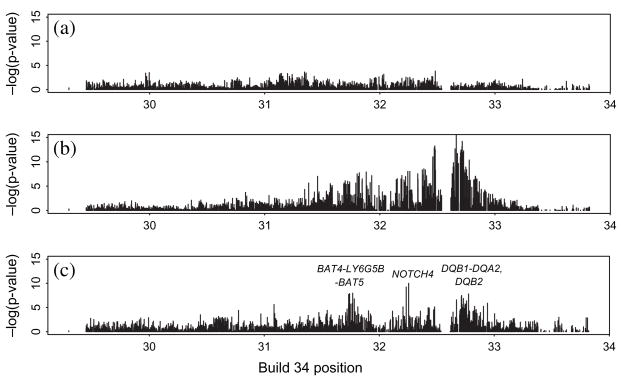

Fig. 4.

Comparison of observed and expected single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotype frequencies given parental genotypes, by affected status of the offspring. (a) Overall comparisons for probands and corresponding unaffected sibs. (b) Analyses for informative parents, one of whom is homozygous for the minor SNP allele.

SNP missingness in the first-listed unaffected offspring was compared with the genotype of the corresponding proband in these families using log-linear analyses (figure 5a). Given the number of comparisons made, there were few regions showing major signs of significant association, and while the sample sizes here were smaller than in previous analyses, impacting on the power of the comparison, the results suggest that inferences based on comparisons of affected and unaffected offspring may not be strongly influenced by informative SNP missingness. In light of this, we compared affected and unaffected sibling SNP genotypes using unadjusted McNemar tests (figure 5b) and adjusted mixed effects regression with the number of major SNP alleles as response (figure 5c). The analyses were carried out within each informative parental genotype class with test statistics combined over the classes, and for the mixed models with adjustment made for HLA-DRB1*03/04/15 genotype status and cohort membership as described in Materials and Methods. Associations with p < 10−7 are found with SNPs near BAT4-LY6G5B-BAT5, NOTCH4 and HLA-DQB2, and between HLA-DQB1 and HLA-DQA2, the latter most likely resulting from inadequate modelling of strong haplotypic associations with the HLA-DRB1*03/04/15 genotypes [11]. None of these fall in the regions associated with missingness found above, and while they are not highly significant, they may point to potential susceptibility regions additional to the classical HLA-DR3/4 alleles.

Fig. 5.

(a) Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) missingness in the first-listed unaffected offspring is not strongly associated with SNP genotype of the corresponding proband – association p values by SNP position. (b) Unadjusted comparison of proband and unaffected sib SNP genotypes by McNemar tests. (c) Comparison of proband and unaffected sib SNP genotypes analysed by mixed effects regression adjusting for HLA-DRB1*03/04/15 status, parental genotype and cohort membership. The more significant associations occur at SNPs near BAT4-LY6G5B-BAT5, NOTCH4 and HLA-DQB2, and between HLA-DQB1 and HLA-DQA2.

Discussion

The analyses reported here point to significant missingness in the SNP fine-mapping data related to HLA genotype that could potentially influence the assessment of markers of disease in the MHC. While further clarifying work is needed for genotypes other than HLA-A24, initial analyses suggest that at least some of the missingness results from HLA-related deletions in the sequence, an assessment supported by the over-representation of homozygous SNPs associated with the genotype. We speculate that other regions of associated missingness noted here may point to similar haplotypic deletions, an aspect which should be considered when undertaking large-scale SNP studies. Deletions/insertions and SNP intensities are likely to affect typing outcomes, including missingness, and while the MHC is at the extreme end in these respects other regions in the genome may also be subject to similar issues.

In light of these findings, we believe it would be prudent to check for potentially informative missingness wherever significant SNP markers are found in this or similar studies within the highly polymorphic MHC region. Although not presented here, similar patterns of HLA association are also found for microsatellite data, with corresponding clusters of significant association found near the respective HLA regions. Informative missingness is likely to have most impact on TDT-type analyses that rely on postulated transmission probabilities [1], while analyses that compare groups may be less susceptible to bias if the effect of missingness is similar in both groups. Our preliminary analyses suggest that comparisons based on affected status may not be significantly affected, although our comparison is limited by the relatively smaller number of families with both affected and unaffected siblings in this study and the possibility that type 1 diabetes may subsequently be diagnosed in some unaffected offspring.

Supplementary Material

Missingness in proband SNP values associated with carriage of HLA genotype. Associations were assessed for each two-digit HLA type. The plots provide log10 p values by Build 34 coordinates with p values truncated at 10−15.

Acknowledgments

Our thanks to David Nolan and Munish Mehta for useful discussions and assistance with the work. This research utilizes resources provided by the T1DGC, a collaborative clinical study sponsored by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), and Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International (JDRF) and supported by UO1 DK062418. The work was also supported by the Diabetes Research Foundation of Western Australia (G. M.), and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (G. M., I. J.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest in the publication of this article.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting information supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- 1.Allen AS, Rathouz PJ, Satten GA. Informative missingness in genetic association studies: case-parent designs. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:671–680. doi: 10.1086/368276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watanabe Y, Tokunaga K, Geraghty DE, Tadokoro K, Juji T. Large-scale comparative mapping of the MHC class I region of predominant haplotypes in Japanese. Immunogenetics. 1997;46:135–141. doi: 10.1007/s002510050252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conrad DF, Andrews TD, Carter NP, Hurles ME, Pritchard JK. A high-resolution survey of deletion polymorphism in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2006;38:75–81. doi: 10.1038/ng1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Estivill X, Armengol L. Copy number variants and common disorders: filling the gaps and exploring complexity in genome-wide association studies. PLOS Genet. 2007;3:1787–1799. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Longman-Jacobsen N, Williamson JF, Dawkins RL, Gaudieri S. In polymorphic genomic regions indels cluster with nucleotide polymorphism: quantum genomics. Gene. 2003;312:257–261. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(03)00621-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hinds DA, Kloek AP, Jen M, Chen X, Frazer KA. Common deletions and SNPs are in linkage disequilibrium in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2006;38:82–85. doi: 10.1038/ng1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCarroll SA, Hadnott TN, Perry GH, et al. Common deletion polymorphisms in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2006;38:86–92. doi: 10.1038/ng1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tokunaga K, Kay PH, Christiansen FT, Saueracker G, Dawkins RL. Comparative mapping of the human major histocompatability complex in different racial groups by pulsed field gel electrophoresis. Hum Immunol. 1989;26:99–106. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(89)90095-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tokunaga K, Saueracker G, Kay PH, Christiansen FT, Anand R, Dawkins RL. Extensive deletions and insertions in different MHC supratypes detected by pulsed field gel electrophoresis. J Exp Med. 1988;168:933–940. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.3.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaudieri S, Kulski JK, Dawkins RL, Gojobori T. Different evolutionary histories in two subgenomic regions of the major histocompatibility complex. Genome Res. 1999;9:541–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pugliese A, Eisenbarth GS. Type 1 Diabetes mellitus of man: genetic susceptibility and resistance. In: Eisenbarth GS, editor. Type 1 Diabetes: Molecular, Cellular and Clinical Immunology, Chapter 7. Springer; New York: 2004. pp. 170–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Missingness in proband SNP values associated with carriage of HLA genotype. Associations were assessed for each two-digit HLA type. The plots provide log10 p values by Build 34 coordinates with p values truncated at 10−15.